Abstract

Vc H-NOX (or VCA0720) is an H-NOX (heme-nitric oxide and oxygen binding) protein from facultative aerobic bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It shares significant sequence homology with soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), a NO sensor protein commonly found in animals. Similar to sGC, Vc H-NOX binds strongly to NO and CO with affinities of 0.27 nM and 0.77 μM, respectively, but weakly to O2. When positioned in “sliding scale” plot {Tsai, A.-L. et. al. (2012) Biochemistry, 51, pp172-86}, the line connecting logKD(NO) and logKD(CO) of Vc H-NOX is almost superimposable with that of Ns H-NOX. Therefore, the measured affinities and kinetic parameters of gaseous ligands to Vc H-NOX provide more evidence to validate the “sliding scale rule” hypothesis. Like sGC, Vc H-NOX binds NO in multiple steps, forming first a 6-coordinate heme-NO complex with a rate of 1.1 × 109 M−1s−1, and then converts to a 5c heme-NO complex at a rate also dependent on [NO]. Although the formation of oxyferrous Vc H-NOX is not detectable under normal atmospheric oxygen level, ferrous Vc H-NOX is oxidized to ferric form at a rate of 0.06 s−1 when mixed with O2. Ferric Vc H-NOX exists as a mixture of high- and low-spin states and is influenced by binding to different ligands. Characterization of both ferric and ferrous Vc H-NOX and their complexes with various ligands lay the foundation for understanding the possible dual roles in gas and redox sensing of Vc H-NOX.

Heme sensor proteins exhibit selective reversible binding of diatomic gaseous molecules, including CO, NO and O2, and play important roles in physiological inter- and intracellular signaling (1–4). The selectivity of heme sensor proteins in association with these small gaseous molecules is determined by several factors including the type of proximal ligand, direct distal steric hindrance, proximal constraints for in-plane iron movement, presence of distal site hydrogen bond donor and multiple steps in association with NO (3). A 3 – 4 orders of magnitude increase from KD(NO) to KD(CO) to KD(O2), regardless of the absolute value of individual KD, is observed for many 5-coordinate (5c) ferrous hemoproteins and protophorphyrin IX (1-Methylimidazole) (PP (1-MeIm)) heme model with a neutral imidazole proximal ligand but lacking a distal hydrogen bond donor. The logKD(NO), logKD(CO) and logKD(O2) of each of these hemoproteins and heme model PP(1-MeIm) fall on an approximately straight line when plotted versus gaseous ligand type, and these lines approximately parallel one another and span a 9-order vertical range, and is recently coined “sliding scale rule” (5). If such a hypothesis is proven valid with large data base, it will establish a paradigm for the gaseous ligand selectivity by a plethora of heme-based sensors. Thus KD measured for one gaseous ligand can be used to predict the affinities of the other two gaseous ligands via the parallel relationship with that of the heme model. The validity of “sliding scale rule” hypothesis has been checked against more than a hundred hemoproteins, mutants and model compounds; however, to validate this hypothesis as a general rule, it is necessary to characterize the binding of gaseous ligands for additional heme sensor proteins to gain statistical support.

Soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), the only authentic NO receptor found in mammalian systems, catalyzes the conversion of GTP to cGMP (6). sGC is a heterodimer, containing α and β subunits and the ferrous heme in the β subunit exhibits strong affinity for NO but no binding with O2 (6, 7). NO binds to sGC to form a 6-coordinate (6c) NO-heme-His complex with subsequent conversion to a 5c NO-heme complex, and stimulates its guanylate cyclase activity by several hundred folds (8, 9). The affinities of NO and CO for sGC to form the 6c complexes are 54 nM and 260 μM, respectively, positioning well in the “sliding scale” plot (5). Based on the affinities of NO and CO to sGC, the KD(O2) of sGC is predicted to be well above oxygen concentration in aqueous solution, ~ 260 μM at 24 °C, thus explains the total exclusion of O2 binding from sGC (5).

sGC belongs to H-NOX (heme-nitric oxide and oxygen binding) or SONO (sensor of NO) (10) family of heme sensor proteins found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (7). H-NOX proteins exhibit high sequence and structure homology to the β subunit of sGC and selectively bind NO or O2 based on the immediate structure of their heme pockets (2, 3, 7, 11). A subgroup of H-NOX proteins, exemplified by the heme domain of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, binds O2 with high affinity (12). This is due to the existence of a hydrogen bond donor, Tyr140, in its heme distal pocket, leading to selectively enhanced binding of O2 (7, 13). Other H-NOX proteins, including eukaryotic sGC and a prokaryotic H-NOX from Nostoc punctiforme (Ns H-NOX), have hydrophobic distal heme pockets without any hydrogen-bonding donor (9, 14). The characteristics of gaseous ligand-binding to Ns H-NOX, which shares 33% sequence identity with the β subunit of human sGC, are similar to those of sGC (14). Ferrous Ns H-NOX binds NO and CO with KD’s of 0.17 nM and 1.4 μM respectively, and the line connecting the two log(KD)’s parallels that of sGC in the “sliding scale” plot (5). Based on its stronger affinity for NO compared to that of sGC, its KD for O2 is expected to be lower than that of sGC; and is actually measured to be 13 mM using a high pressure cell (5). This [O2] is still much higher than that available under atmospheric pressure and therefore Fe(II) Ns H-NOX does not exhibit appreciable O2 binding either.

Another H-NOX protein identified from the genome of a facultative aerobic bacterium Vibrio cholerae, Vc H-NOX (also called VCA0720), is a protein of 181 amino acid and shares 22% sequence identity with rat sGC β1 subunit (1-194) (12). Initial spectroscopic studies indicate that Fe(II) Vc H-NOX selectively binds NO and CO but shows no binding to O2, similar to sGC and Ns H-NOX (12). Resonance Raman spectroscopy indicates that Fe(II) Vc H-NOX exists in high-spin state (12). Ferrous Vc H-NOX binds CO readily to form 6c heme-CO complex and NO to form 5c heme-NO complex in the presence of excess amount of NO (12). Information of KD’s and binding kinetics of NO and CO to Vc H-NOX, however, is lacking. Moreover, it is unknown whether NO binds to Vc H-NOX in multiple steps, as observed in some H-NOX proteins like sGC and Ns H-NOX (8, 14).

In this study, we determined the binding affinities and the kinetics of gaseous ligands to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX and checked the validity of “sliding scale rule” hypothesis using the measured parameters. Our results demonstrate that the bindings of NO and CO to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX are consistent with the “sliding scale rule” hypothesis, which also nicely explains why O2 does not bind to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX. NO is found to bind Fe(II) Vc H-NOX in multiple steps. Some differences were observed between the binding kinetics of NO and O2 to Vc H-NOX and to sGC and Ns H-NOX. We also studied the heme geometry in ferric Vc H-NOX and its complexes with ligands using magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). This study provides new information the possible signaling pathways for this human pathogen to respond to the environmental NO level and the redox states, and therefore should provide insight into the virulence of this human pathogen mediated via either the ferrous or ferric state of the heme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Carbon monoxide (CO) and nitric oxide (NO) gases were from Matheson-TriGas Inc. (Houston, TX). NO was pre-purified by passing through a NaOH trap to remove nitrous and nitric acid contaminants. Sodium ferricyanide, sodium hydrosulfite (85%), sodium fluoride, sodium azide, sodium cyanide, imidazole, δ-aminolevulinic acid and isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cyanide stock solution (1M), ~pH 9, was prepared by titration of water solution of sodium cyanide with HCl at 0 °C. Other chemicals are all of reagent grade.

Construction of the expression vector for His-tagged Vc H-NOX

Gene sequence of Vc H-NOX (GenBank Accession No. GI:15601476) was first optimized for Escherichia coli codon usage, replacing several rare codons with high-frequency synonymous codons to form a synthetic gene encoding Vc H-NOX. Six histidine codons were then inserted upstream of the stop codon and the Vc H-NOX cDNA was synthesized and cloned into pBSK vector (Epoch LifeScience, Houston, TX). The cDNA was released by digesting with NdeI and XhoI and sub-cloned into pET43.1a (pre-digested by NdeI and XhoI). The integrity of the resulting plasmid was confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing (Lone Star Labs, Houston, TX).

Expression and purification of Vc H-NOX

Rosetta 2(DE3)pLysS E. coli strain (Novagen, Madison, WI) was transformed with the pET43.1a Vc H-NOX expression plasmid and grown overnight in Terrific Broth medium containing chloramphenicol (45 μg/mL) and ampicillin (150 μg/mL) at 37 °C. The overnight culture was used to inoculate Terrifc Broth containing ampicillin (150 μg/mL) and incubated with shaking (200 rpm) at 37 °C until the A610 reached 0.8. After chilling to 20 °C, heme (2 μM), δ-aminolevulinic acid (0.2 mM), and isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (1 mM) were added, and the culture was shaken for 48 h at 20 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation.

To purify Vc H-NOX, cells were resuspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5 containing 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and egg lysozyme (1 mg/mL). The suspension was stirred at 4 ºC, sonicated and then centrifuged at 100,000g. The supernatant containing recombinant Vc H-NOX was then mixed with TALON affinity resin (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). Vc H-NOX was eluted with the same buffer containing 250 mM imidazole, which was later removed using 10 DG desalting columns.

Purity of the purified Vc H-NOX was checked with 12% SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The amount of protein was determined with a Bio-Rad kit (Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. The heme content was determined by the pyridine hemochrome method based on A556 – A538 = 24.5 mM−1 cm−1.

Electronic absorption and magnetic circular dichroism (MCD)

Electronic absorption spectra were recorded using a Hewlett-Packard 8452A diode-array spectrophotometer with an optical resolution of 2 nm. MCD spectra in UV-vis region were recorded with a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan). The magnetic field was provided with an Olis magnet (Bogart, GA) and the field strength was calibrated with a ferricyanide solution using ΔA420 = 3.0 M−1cm−1T−1. Experiments were conducted at room temperature at a bandwidth of 5 nm, 0.5 s time constant, 0.5 nm resolution from 250 nm to 700 nm at a 200 nm/min scan speed. Each spectrum is an average of 4 to 10 repetitive scans. Near-infrared MCD (NIR MCD) spectra between 700 – 1850 nm were obtained using a JASCO J-730W spectropolarimeter equipped with a 150 W tungsten halogen light, a high-sensitivity InSb detector cooled with liquid nitrogen and a JASCO 1.4 T electromagnet. NIR MCD data was collected at room temperature at a bandwidth of 10 nm, 1 s time constant, 1 nm resolution at a 500 nm/min scan speed. Each spectrum is an average of 12 or 16 scans. MCD expressed in molar delta absorption coefficient, ΔA, in units of M−1cm−1T−1, was calculated as using the spectral analysis software that came with the instruments. MCD data between 500 – 700 nm was smoothed by moving average algorithm performed using the same software.

The CO complex of Vc H-NOX was prepared by injecting desired volume of CO saturated anaerobic buffer (1 mM) into cuvette containing Fe(II) Vc H-NOX sealed with an airtight septum. The NO complex was prepared similarly except that the NO stock (2 mM) was prepared in anaerobic water. The buffer used in all the experiments was 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3 with 50 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol except in two situations. For preparing the NO complex, 50 mM TEA, pH 7.4 was used. In NIR MCD experiment, samples of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its complexes were in 20 mM HEPES with 50 mM NaCl prepared in D2O.

Stopped-flow experiments

The association and dissociation kinetics of gaseous ligands to anaerobic Fe(II) Vc H-NOX were studied by an Applied Photophysics (Leatherhead, UK) model SX-18MV stopped-flow instrument, and optically following the absorbance changes at different wavelengths with a monochromator or the whole spectral changes with a diode-array accessory. The sample handling unit was kept in an anaerobic chamber by COY Lab Products, Inc. (Grass Lake, MI). Ferrous Vc H-NOX used in all the experiments was prepared by sodium hydrosulfite titration after five cycles of vacuum and argon displacement in a tonometer. Diode-array data was analyzed with the global analysis method using Pro-K package (Applied Photophysics). Observed rate constants, kobs, of single wavelength data under pseudo-first order conditions ([L]/[Vc H-NOX] > 10), were obtained by fitting the profiles of optical changes to the standard exponential function:

| [1] |

where Af is the final optical absorbance, t is the reaction time and a the amplitude of change in reactions. Second order association rate constant kon and dissociation rate constant koff were derived from the slope and y-intercept, respectively, in the secondary plots of kobs versus gaseous ligand concentration [L]:

| [2] |

In this study, koff constants for the NO and CO complexes with Vc H-NOX are small and fitting errors prevent extracting their accurate values based on the y-intercepts of this type of plot. Dissociation constants were therefore determined using competition methods as explained in Results section.

When measuring the formation rate of the 6c NO complex, Vc H-NOX was mixed with equal concentration of NO, and the kobs was obtained by fitting the time-dependent optical change with the following equation:

| [3] |

where A0 is the initial optical absorbance. Second order rate constant in unit of M−1s−1 was obtained by multiplying kobs with the difference extinction coefficient.

EPR spectroscopy

EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker EMX spectrometer. Data analyses and spectral simulations were conducted using WinEPR and SimFonia programs furnished with the EMX system. Liquid nitrogen EPR (115 K) was conducted under the following conditions: frequency, 9.29 GHz; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 2.0 G and time constant, 0.33 s. The conditions for liquid helium EPR (10 K) were the same except for the frequency, 9.58 GHz and the modulation amplitude, 5 or 10 G. The microwave power dependence was fit by nonlinear regression to the following equation:

| [4] |

where P is the microwave power, S is the peak-to-trough amplitude of EPR signal, P1/2 is the microwave power at half-saturation, and b and K are floating parameters with b = 1 or 3 for nonhomogeneous and homogeneous line-broadening, respectively (15). EPR samples of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX-NO complex were prepared by rapid mixing Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with desired levels of NO using a rapid freeze apparatus (Update Instrument, Madison, WI) placed inside an anaerobic chamber. The mixtures were shot into EPR tubes and freeze-trapped within 1–2 s in an ethanol/dry ice mixture.

Computer modeling

Optical changes at 420 nm of the Fe(II) Vc H-NOX reaction with NO under pseudo first-order conditions were simulated using SCoP Program (Simulation Resources Inc., Redlands, CA). The model used was based on Scheme 1: B ↔ C → D. Rate constants for reaction C → D and extinction coefficients for both 6c and 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complexes were set to the values determined experimentally. The rate constants for reaction B ↔ C, and the extinction coefficient for the putative transient quaternary complex were allowed to float.

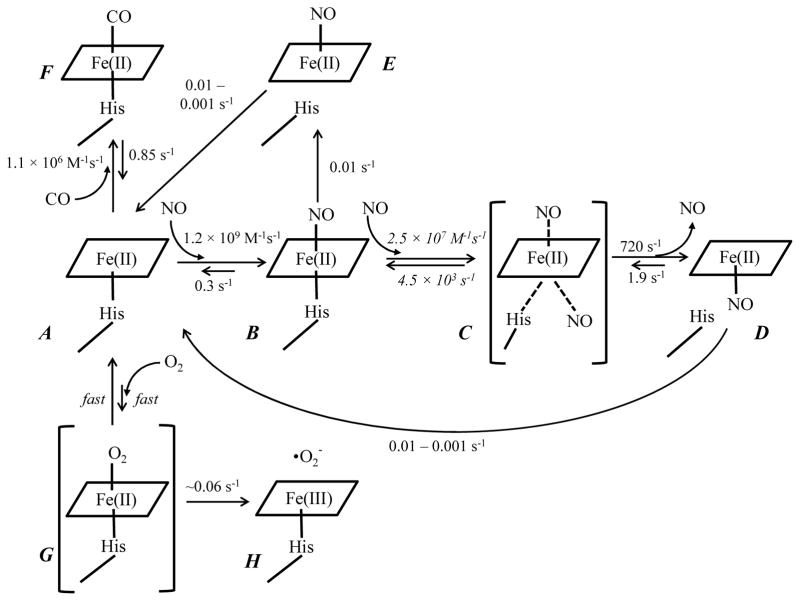

Scheme 1.

Binding of gaseous ligands to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX. Each heme species is labeled in red. The rate constants labeled in italic are estimated by simulation. Both association and dissociation of O2 to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX are assumed to be fast and the rate constants are not determined. Intermediates C and G, bracketed in parentheses, are not observed in experiments and presumably only exist transiently. Intermediate C may be a quaternary complex as proposed in (8).

RESULTS

Expression and purification of Vc H-NOX

The typical yield of purified Vc H-NOX from our bacterial expression was ~ 27 mg per liter of cell culture and the purity was estimated to be above 95% based on SDS-PAGE (data not shown). The estimated molecular weight, 21.5 kDa, agrees well with the expected value (12). Pyridine hemochrome analysis indicates a non-covalently bound b type heme, with a stoichiometry of 0.94 ± 0.03 (n = 3) heme per Vc H-NOX monomer. The Soret absorption of purified Vc H-NOX is typically between 410 – 412 nm (data not shown). However, the Soret peak shifts to 406 nm upon oxidation by ferricyanide or to 428 nm upon reduction by sodium hydrosulfide, indicating the oxidation state of heme in purified Vc H-NOX is a mixture of ferric and ferrous states. The determined extinction coefficients of ferric and ferrous Vc H-NOX are 115.4 and 145 mM−1cm−1, respectively (Table S1 in supporting materials), similar to the published values (12).

Electronic absorption and MCD spectroscopy of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX and its complexes with CO and NO

Ferrous Vc H-NOX exhibits a Soret band at 428 nm and a Q band at 558 nm. Association of CO to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX shifts the Soret peak to 422 nm, with an extinction coefficient of 210.0 mM−1cm−1, and the Q band splits into two maxima at 540 nm and 568 nm (Fig. 1A and Table S1). The wavelength of the Soret peak of Vc H-NOX-CO complex is similar to those of myoglobin-CO (Mb-CO), sGC-CO and Ns H-NOX-CO complexes, indicating a 6c low-spin heme (Scheme 1, F) (12, 14, 16). Mixing Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with excess amount of NO shifts the Soret peak to 398 nm, with an extinction coefficient of 99.1 mM−1cm−1, and the Q band to 572 nm with a shoulder at 538 nm (Fig. 1A and Table S1). The electronic absorption spectrum of Vc H-NOX-NO complex is very similar to that of the 5c sGC-NO complex (Scheme 1, D) (8).

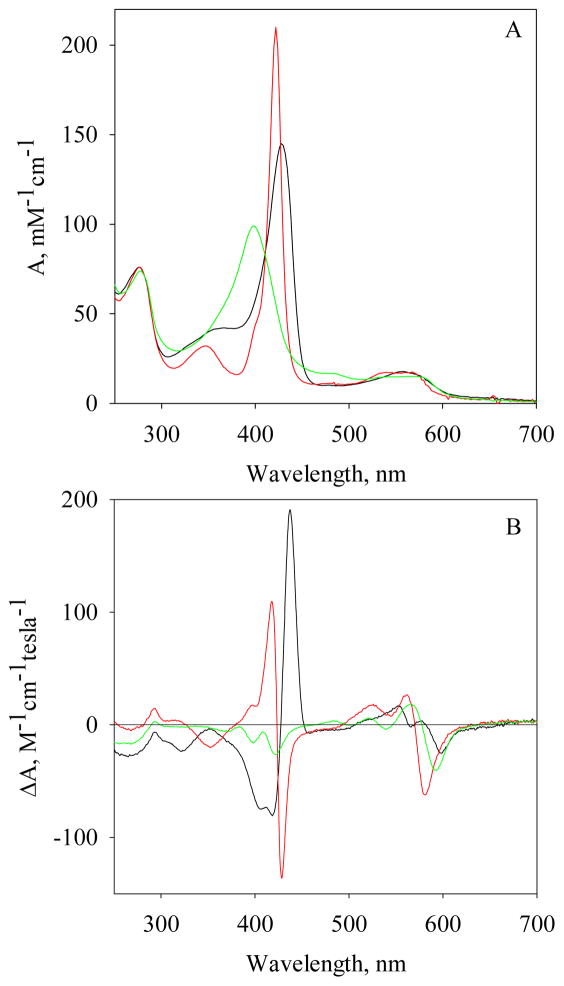

Figure 1.

Electronic absorption and MCD spectra of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX and its complexes with CO and NO. The electronic absorption spectra (A) and MCD spectra (B) of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX (6.3 μM) and its complexes are represented using different colors: Fe(II) Vc H-NOX, black; CO complex, red and 5c NO complex, green. The complexes were prepared using the following ratios: [CO]/[Vc H-NOX] = 6 and [NO]/[Vc H-NOX] = 4.

In the Soret region, MCD spectrum of unliganded Fe(II) Vc H-NOX exhibits a split trough between 405 nm – 418 nm, with intensities of −70.7 – −76.1 M−1cm−1T−1, and a peak at 437 nm, with an intensity of 180.4 M−1cm−1T−1 (Fig. 1B and Table S1). The crossover is at 427 nm, corresponding to the Soret peak of its electronic absorption spectrum. The lineshapes of both Soret and Q bands are similar to those of deoxymyoglobin (17), indicating a high-spin ferrous heme in the unliganded Fe(II) Vc H-NOX. The MCD spectrum of Vc H-NOX-CO complex exhibits a peak of 103.4 M−1cm−1T−1 at 428 nm and a tough of −128.3 M−1cm−1T−1 at 428 nm, with a crossover at 423 nm (Fig. 1B and Table S1). The lineshapes of both Soret and Q bands are very similar to those of Mb-CO complex (17), confirming a 6c low-spin heme in Vc H-NOX-CO complex. The MCD of Vc H-NOX-NO complex exhibits bands of significantly lower intensities compared to those of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX and its CO complex, and the major signatures include a trough of −20.5 M−1cm−1T−1 at 399 nm and a derivative-shaped feature centered at 579 nm (Fig. 1B and Table S1). These features are similar to what were observed for H93G Mb-NO complex in the presence of 1 mM imidazole (17) and a 5c ferrous heme–NO model compound, verifying that heme in Vc H-NOX-NO complex in the presence of excess amount of NO is in a 5-coordinate state (Scheme 1, D).

Kinetics of CO binding to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX

The binding of CO to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX is a simple reversible one-step reaction with no spectral intermediate when examined by rapid scanning stopped-flow spectrophotometry (data not shown). The kinetics of CO binding was determined by following the time courses at 423 nm under pseudo-first-order reaction conditions using ~1.3 μM Fe (II) Vc H-NOX and varying [CO] from 50 to 500 μM at 24 °C (Fig. 2A). The rate constants kobs were obtained by fitting to a single exponential function (Eq. [1]). The plot of kobs versus [CO] exhibits a linear dependence on [CO] and a second-order association rate constant, kon(CO) = 1.1 × 106 M−1s−1 (Table 1), was obtained from the slope (Eq. [2] and Fig. 2A, inset). The total absorbance changes are the same for all [CO], indicating that complete saturation with CO was achieved with each [CO], and the KD for CO binding is therefore much lower than 50 μM. The dissociation rate constant, koff, was measured with the NO displacement method (18) by reacting Vc H-NOX-CO complex with 1 mM NO and following the change of A423 (Fig. 2B). Fitting the time course of A423 to Eq. [1] yielded koff(CO) = 0.85 s−1 (Fig. 2B, inset & Table 1). The equilibrium dissociation constant, KD(CO), is calculated to be 0.77 μM (Table 1).

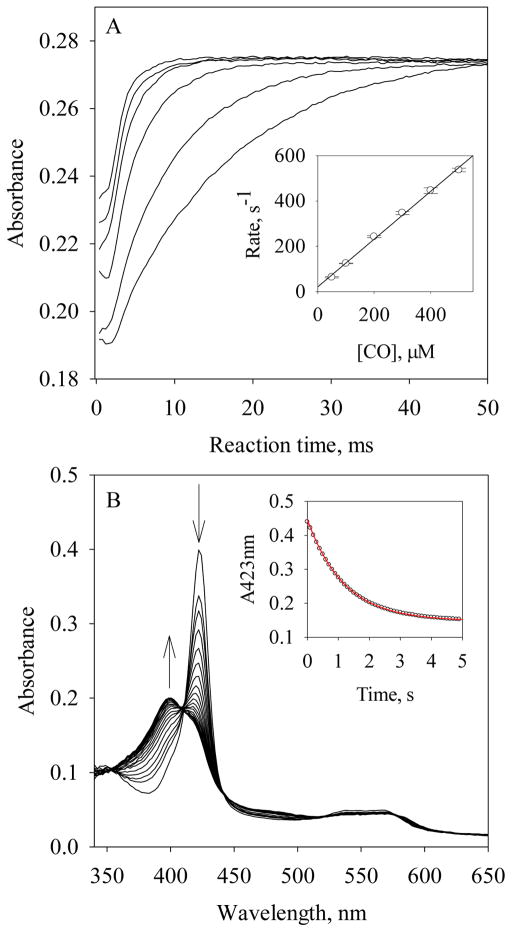

Figure 2.

Determination of kon(CO) and koff(CO) to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX. (A) Time-dependent changes of A423 during the reactions of ~1.3 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with 50, 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 μM CO (from bottom to top) at 24 °C. (Inset) The observed rate constants, kobs (circle), and the linear regression of the data. The error bars are the standard deviations of four individual measurements. (B) Time-dependent change of A423nm during the reaction of ~2.1 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX/25 μM CO with 1 mM NO at 24 °C. (Inset) Time course of A423 nm (black). The red line represents the fit to Eq. [1].

Table 1.

The parameters kon, koff and KD of gaseous ligands to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX

| ligand | kon, M−1s−1 | koff, s−1 | KD, μM |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO | 1.1 × 109 | 0.3 | 2.7 × 10−4 |

| CO | 1.1 × 106 | 0.85 | 0.77 |

| O2 | - | - | (~ 1.3 × 103)a |

estimated based on the KD’s of CO and NO and the “sliding scale rule” (Fig. 12).

Reaction of O2 with Fe(II) Vc H-NOX

The Soret peak slowly shifted from 428 nm to 412 nm during the reaction of ~3 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with 600 μM O2, followed by rapid scanning stopped-flow spectrophotometry (Fig. 3A). The ending wavelength is similar to that of the resting Vc H-NOX (Fig. 3A). In the same time period, Q band shifted from 558 nm to 534 nm (Fig. 3A). No well-defined isosbestic point(s) was observed around the Soret peak, implying that multiple steps are involved in the transition. However, no intermediate with clear sign of Fe(II) heme-O2, which usually gives a split Q band and a Soret peak ~415 nm (16), is resolved from the spectral change. The spectral changes thus appear to be an autoxidation from Fe(II) Vc H-NOX to its ferric state, with very transient formation of Fe(II) heme-O2 (Scheme 1, G to H).

Figure 3.

Autoxidation of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX by O2. (A) Spectral changes during the reaction of 3 μM Fe (II) Vc H-NOX with 600 μM O2 at 24 °C, monitored for 65.5 s. An absorption spectrum of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX, with a Soret peak at 428 nm, is presented as the starting point at 0 s. The absorption between 500 – 650 nm is scaled up by a factor of 5 for easy comparison (right). The slant arrows indicate the direction of wavelength shift and the change of amplitude. (B) Stopped-flow of 3 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 and 0.6 mM O2 at 24 °C (from top to bottom). (Inset) The observation rate constants, kobs (circle), are plotted versus [O2] and fit with linear regression. The error bars are the standard deviations of four individual measurements.

When 3 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was reacted with O2 varying from 100 to 600 μM, the extents of change of the time courses at 429 nm increased with [O2] (Fig. 3B), indicating no saturation was reached even at the highest [O2] available with oxygenated buffer and the KD(O2) to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX is therefore at least higher than 600 μM. Each kinetic trace was fitted well with one exponential function (Eq. [1]) and the kobs constants exhibit linear dependence on [O2] (Fig. 3B, inset). Slope of kobs versus [O2] yielded a second order reaction rate constant, 4.8 M−1s−1, based on which the autoxidation rate of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX to ferric state was estimated to be ~0.06 s−1 (see Discussion).

Binding of NO to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX

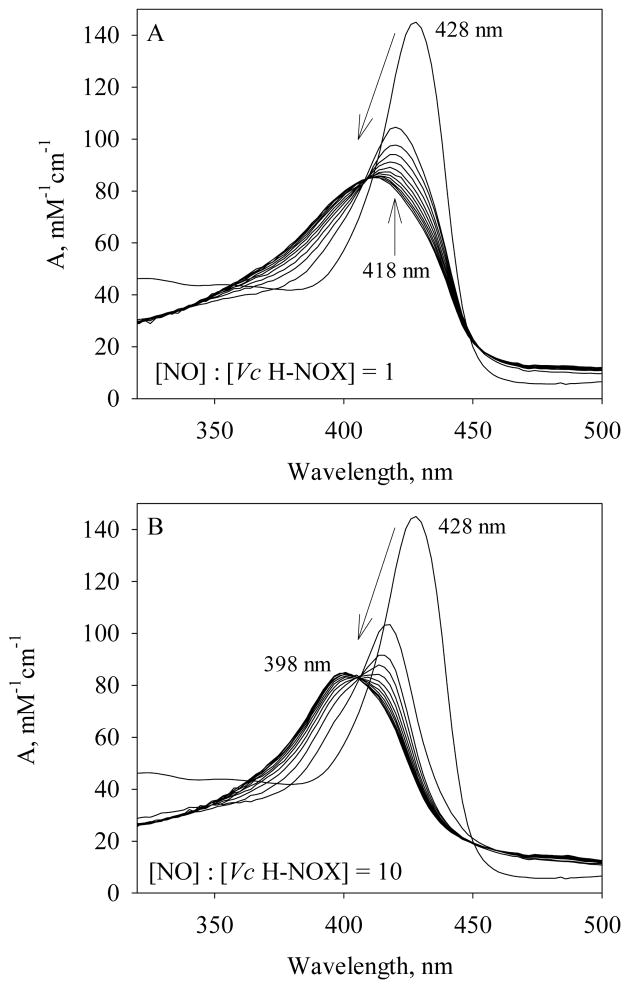

The rapid-scanning diode-array measurements of NO binding to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX were conducted using either stoichiometric amount (Fig. 4A) or 10-fold of NO versus Fe(II) Vc H-NOX (Fig. 4B). Stoichiometric amount of NO binds to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX in a single rapid phase, with the Soret peak shifting from 428 nm to 418 nm and an isosbestic point at 420 nm (Fig. 5A). This indicates the formation of a 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex (Scheme 1, B), similar to what was observed for Ns H-NOX and sGC (5, 8, 14). Most of the reaction was lost in the 1.5 ms dead time of the stopped-flow apparatus, indicating a very large kon(NO). The 418 nm Soret peak slowly shifted to 414 nm with an isosbestic point at 410 nm after ~ 1 min (Fig. 4A) and continued to shift very slowly to 399 nm (data not shown). The overall conversion rate was ~0.01 s−1 determined by global analysis. This suggests that the stoichiometric binding of NO to Vc H-NOX results in slow dissociation of the proximal histidine and a 5c NO-heme complex, with NO on the distal side of heme (Scheme 1, E). In the presence of excess amount of NO, the formation of 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex was complete in the dead time of the stopped-flow apparatus and the Soret peak quickly shifted to 398 nm (Fig. 4B), indicating conversion to a 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex (Scheme 1, D). Although no intermediate(s) was resolved for Vc H-NOX, formation of this 398 nm 5c Vc H-NOX-NO likely goes through a quaternary complex as proposed for the NO binding to sGC (Scheme 1, C) (8).

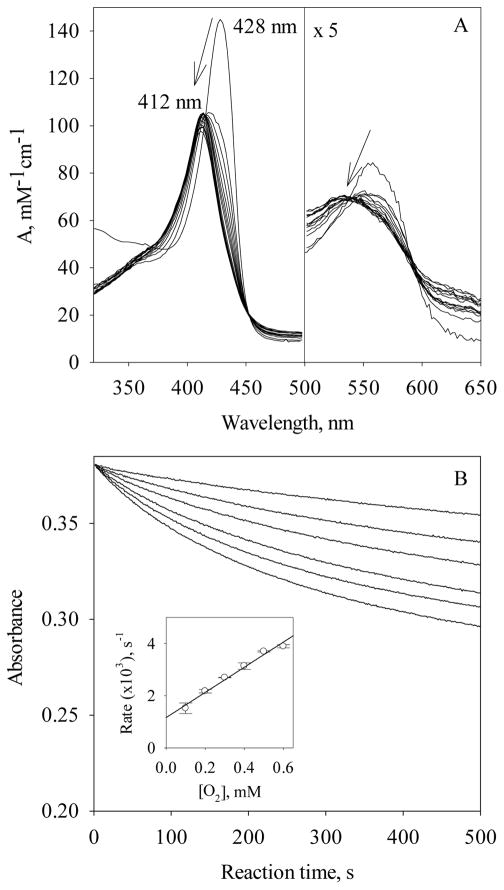

Figure 4.

Spectral changes during NO binding to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX. (A) 2.5 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was reacted with 2.5 μM NO at 24 °C and the spectral change is shown up to 65.5 s. (B) 2.5 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was reacted with 25 μM NO at 24 °C and the spectral change is shown up to 1 s. An absorption spectrum of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX, with a Soret peak at 428 nm, is presented in both panels as the starting spectrum at 0 s. The Soret peaks of the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex at 418 nm and the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex at 398 nm are labeled. The slant arrows indicate the direction of wavelength shift and the change of amplitude.

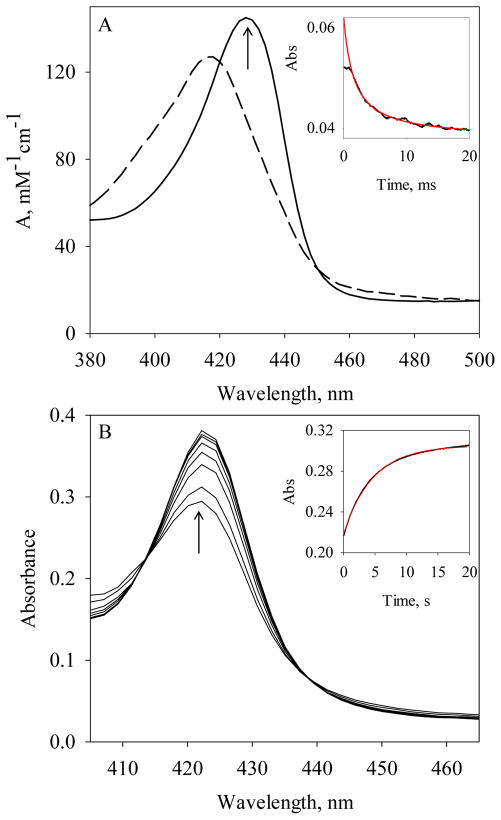

Figure 5.

Determination of kon(NO) and koff(NO) in the formation of the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex. (A) The resolved absorption spectrum of the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex (dashed line) in comparison with that of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX (solid line). Reaction: 0.6 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with 0.6 μM NO at 24 °C. The arrow indicates the wavelength for measuring kon(NO). (Inset) Time course of A429 nm (black). The red line represents the fit to a second-order reaction mechanism (Eq. [3]). (B) Rapid-scanning stopped-flow of the dissociation of the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex. 9.4 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was first mixed with 10 μM NO, aged for 50 ms and then further mixed with 1 mM CO in 25 mM dithionite. (Inset) Time course of A423 nm (black). The red line represents the fit to a single exponential function (Eq. [1]).

To determine the large kon(NO) of 6c Vc H-NOX-NO, we measured the kinetics under true second-order reaction conditions, using a [NO] : [Fe(II) Vc H-NOX] ratio of 1:1 and a final concentration at 0.6 μM each, to avoid missing most of the time course in the dead time of the stopped-flow apparatus (5). The measurements at 429 nm captured ~60% of the total expected changes. The observed time course was fitted to a second-order, irreversible mechanism (Eq. [3], Fig. 5A, inset) and yielded a kon(NO) value of 1.1 × 109 M−1s−1 (Table 1).

The dissociation rate constant, koff(NO), of the initial 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex, with a Soret peak at 418 nm, was measured using sequential stopped-flow method (5). The 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex was generated by reacting 4.7 μM Vc H-NOX with 5 μM NO and the formation of 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex finished within 10 ms. The 6c NO complex was then aged for 50 ms and reacted with 0.5 mM CO in 12.5 mM dithionite to displace and consume the dissociated NO, respectively (5). Exponential increase in A423 was observed following the second mixing (Fig. 5B), indicating the formation of 6c Vc H-NOX-CO complex. Fitting the time course at 423 nm to the single-exponential function (Eq. [1]) yielded a rate constant koff(NO) of 0.3 s−1 (Fig. 5B, inset & Table 1). This rate constant is much slower than kon(CO) to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX (Fig. 2, inset), indicating that the rate of NO displacement by CO is limited by the NO dissociation from the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex. Combined the kon(NO) and koff(NO) constants, the KD(NO) for the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex is calculated to be 0.27 nM (Table 1).

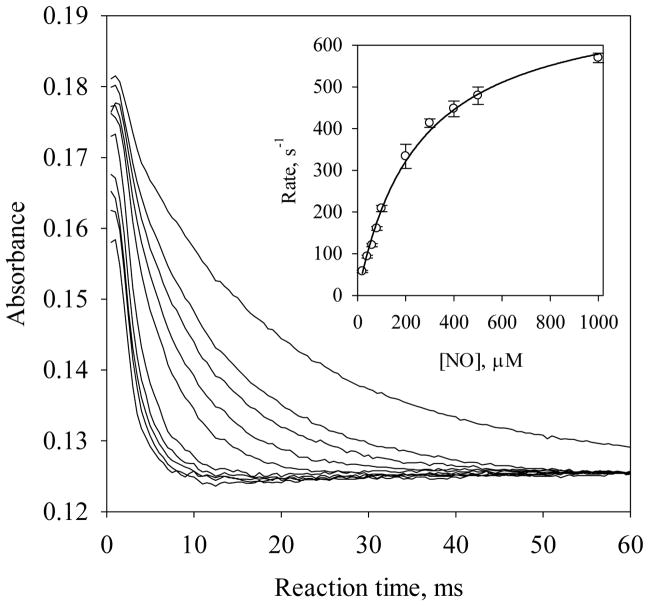

With excess amount of NO, the kinetics of the conversion from the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex to the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex, with a Soret peak at 398 nm, was measured by reacting Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with NO under pseudo first-order conditions and the time courses at 420 nm were followed (Fig. 6). Under these experimental conditions, the formation of 6c Vc H-NOX-NO was complete within the dead time of the stopped-flow apparatus and the kobs’s are the formation rate constants of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex, which presumably forms through a quaternary complex (Scheme 1, B to D), as indicated by the EPR studies of 14NO/15NO binding to sGC (8). When kobs’s are plotted versus [NO], a linear dependence on [NO] is observed at [NO] lower than 50 μM (data not shown), and with higher [NO], the dependence gradually levels off (Fig. 6, inset). This is very different from what was observed for sGC, where kobs for the formation of 5c sGC-NO complex always exhibits a linear dependence on [NO], indicating transition from the hypothetic quaternary complex (corresponding to C in Scheme1) to 5c sGC-NO complex is never rate-limiting (8). For Fe(II) Vc H-NOX, the hyperbolic saturation phenomenon of kobs versus [NO] strongly suggests that the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex forms through a transient quaternary complex, as represented in reactions (1) and (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

Figure 6.

Saturation kinetics for the formation of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex. Time courses of A420 during the reactions of ~1.8 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX with 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500 and 1000 μM NO (from top to bottom) at 24 °C. (Inset) The observed rate constants, kobs (circle), are plotted versus [NO] and fit to Eq. [5] (51). The error bars are the standard deviations of four individual measurements.

At very high [NO], reaction (2) becomes rate-limiting, and k2 = 720 s−1 is determined by fitting the kobs versus [NO] plot with the following hyperbolic function (Fig. 6, inset):

| [5] |

Estimated KM was 250 μM by fitting. Here the re-association rate constant of NO with 5c Vc H-NOX to form NO-heme--NO(--His) complex, k-2 = 1.9 s−1, was obtained from the y-intercept of kobs versus low [NO] (data not shown). A computer model was built based on reactions (1) and (2) to simulate the kinetic events during the formation of 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex. Satisfactory simulation was obtained with k1 and k-1 set as 2.5 × 107 M−1s−1 and 4.5 × 103 s−1, respectively (Fig. S1 in supporting materials).

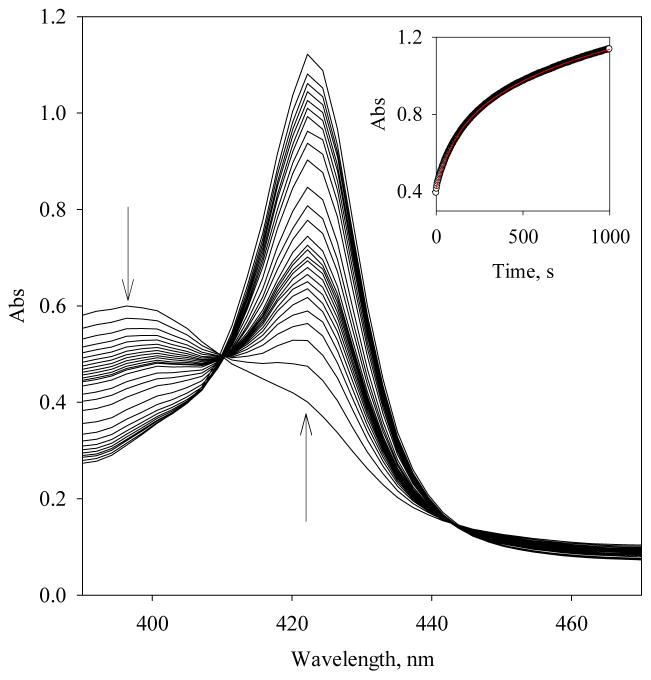

The dissociation rate constants, koff, of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complexes in the presence of both stoichiometric or excess amount of NO were measured by NO displacement with CO (19). In the presence of excess amount of NO, 6.7 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was first reacted with 30 μM NO, and the generated 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex was next reacted with 0.5 mM CO in 12.5 mM dithionite. The Soret peak shifted from 398 nm to that of the 6c Vc H-NOX-CO complex (Fig. 7). The time course at 422 nm indicates that the NO displacement is a biphasic process and fitting to a double exponential function yielded rate constants of 0.01 s−1 (29% overall reaction) and 0.001 s−1 (71% overall reaction) (Fig. 7, inset). In the presence of stoichiometric amount of NO, the NO displacement from the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex is also a biphasic process with the same rates, 0.01 s−1 (16% overall reaction) and 0.001 s−1 (84% overall reaction) (data not shown). In both cases, the kinetics of NO displacement was the same with 50 mM dithionite (data not shown), indicating that the formation rates of Vc H-NOX-CO complex in these measurements are limited by the dissociation of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complexes. The biphasic dissociation of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complexes is probably due to the existence of two different conformations.

Figure 7.

Determination of the dissociation of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex. The spectral change during the rapid-scanning stopped-flow reaction, 13.4 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX/60 μM NO mixed with 1 mM CO/25 mM dithionite, is presented. The arrows indicate the directions of absorbance changes. (Inset) Time courses of A422nm (black circle) and fit to a double exponential function: A = Af + a1e−(kobs, 1) × t +a2e−(kobs, 2) × t (red line).

EPR characterization of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX-NO complex

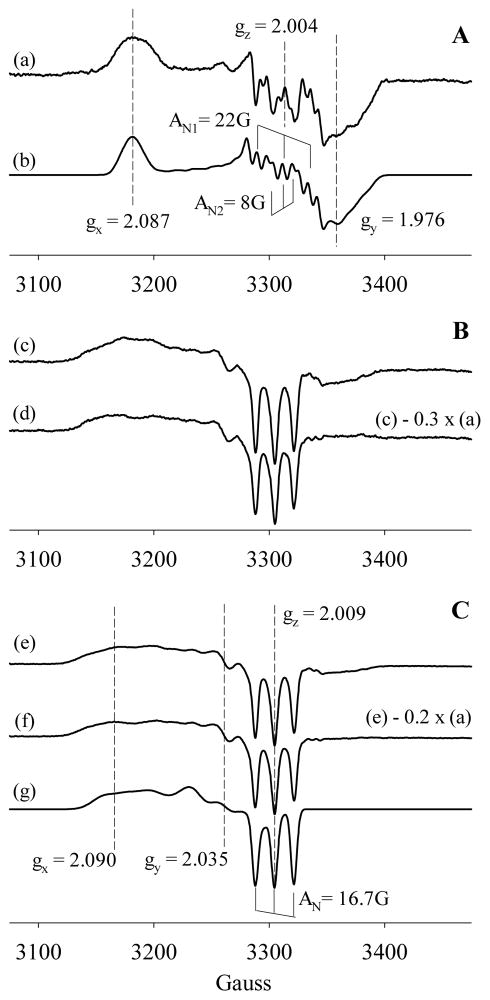

EPR exhibits features of a typical 6c NO complex when Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was reacted with 1:1 NO and freeze-trapped after 1 s (Fig. 8A, spectrum (a)). This is consistent with the observation with rapid scanning stopped-flow (Fig. 4A). The 9-line hyperfine splitting of the gz component can be fit using two different nuclear spin = 1 hyperfine splitting of 22.2 G and 8 G for the nitrogen atoms of NO and the proximal histidine ligand, respectively (Fig. 8A, spectrum (b)). EPR of sample freeze-trapped after 30 s of reaction revealed mainly a 5c high-spin NO complex with minor features due to a 6c NO complex (Fig. 8B, spectrum (c)). Subtraction of ~30% 6c heme-NO EPR yields the spectrum of an almost pure 5c heme-NO complex (Fig. 8B, spectrum (d)), presumably with NO ligated to the distal side of the heme (Scheme 1, E). The conversion rate observed in rapid-freeze EPR experiment was significantly faster than that measured with rapid-scanning stopped-flow spectrophotometry (Fig. 4A). This could be due to the much higher [Fe(II) Vc H-NOX] and [NO] and much lower temperature used in the rapid-freeze EPR compared to those in stopped-flow spectrophotometry. These different experimental conditions may significantly affect the equilibrium between the 6c and 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complexes.

Figure 8.

EPR spectra of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX-NO complexes. Panel A. (a) EPR of the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex, prepared by freeze-trapping of 39 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX reaction with 1:1 NO for 1 s. (b) Simulation of the 6c NO-heme complex using the following parameters: gx = 2.087, gy = 1.976, gz = 2.004; AN1: Ax = 6 G; Ay = 12 G and Az = 22.2 G; AN2: Ax = 6 G; Ay = 12 G and Az = 8 G. Panel B. (c) EPR of the 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex, prepared by freeze-trapping of 39 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX reaction with 1:1 NO for 30 s. (d) EPR spectrum of an approximately pure 5c heme-NO complex, obtained by subtracting spectrum (c) with ~ 30% of (a). Panel C. (e) EPR of the Vc H-NOX-NO complex, prepared by freeze-trapping of 39 μM Fe(II) Vc H-NOX reaction with 1:10 NO for 10 s. (f) EPR of an approximately pure 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex obtained by subtracting 20% (a) from (e). (g) Simulation of the 5c NO-heme complex using the following parameters: gx = 2.090, gy = 2.035, gz = 2.009; AN: Ax = 20 G; Ay = 22 G and Az = 16.7 G.

The EPR spectrum of freeze-trapped sample from Fe(II) Vc H-NOX reaction with 1:10 NO is dominated by a 5c high-spin signal with three distinct hyperfine features contributed by the nitrogen nucleus of NO (Fig. 8C, spectrum (e)). This is consistent with the optical data (Fig. 1A and 4B). Signal of a small portion of 6c heme-NO is still observable and subtraction of ~20% 6c heme-NO EPR yields the spectrum of an almost pure 5c heme-NO complex (Fig. 8C, spectrum (f)). Spectrum of such a 5c complex can be fit using a gz hyperfine splitting constant of 16.7 G (Fig. 8C, spectrum (g)). The EPR features of 5c NO complexes generated with 1 × NO and 10 × NO appear to be very similar (Fig. 8, spectra (d) and (f)), different from the case of sGC where two different sets of 5c NO-heme EPR signatures are detected (20, 21). A microwave power dependence study on 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex yielded a half saturation power of 138 mW and a line broadening factor of 1.6 (data not shown), close to that of inhomogeneous line broadening (22). The large half-saturation power indicates the presence of a fast energy relaxation mechanism via strong spin-orbital coupling.

Electronic absorption and MCD spectroscopy of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its complexes

H-NOX family proteins are likely sensors for gaseous ligands based on the measured selective binding of gaseous ligands and structural homology to sGC. However, the presence of both stable ferric and ferrous states of the purified recombinant Vc H-NOX and the major conformational adjustment during transition from the ferrous to the ferric state observed for Ns H-NOX suggests another possible role of redox sensing of these proteins (14). We therefore also characterized Vc H-NOX in its ferric state and its complexes with different ligands.

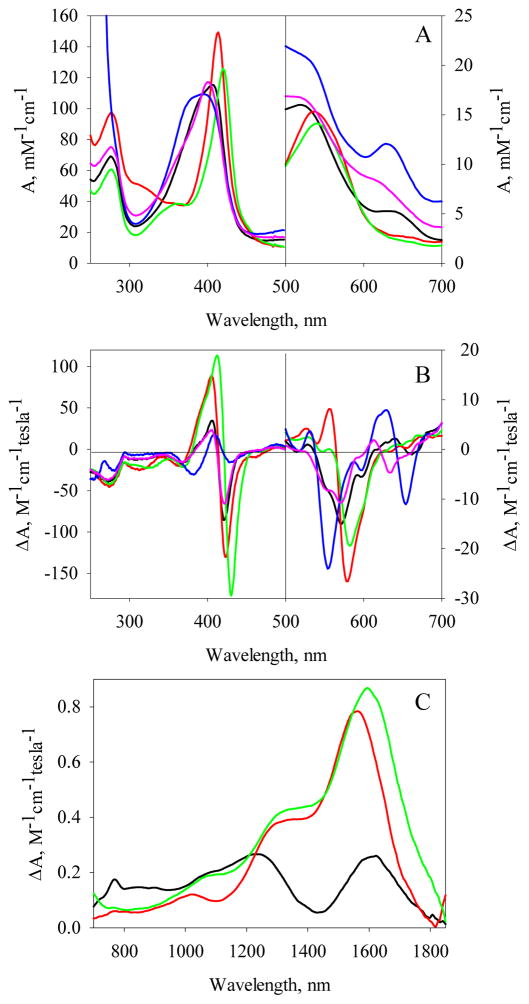

Ferric Vc H-NOX exhibits a Soret peak at 406 nm of 115.4 mM−1cm−1, a Q band at 522 nm and a ligand-to-iron or porphyrin-to-iron charge-transfer band at 636 nm which is characteristic of high-spin heme species (Fig. 9A). The binding of imidazole or cyanide shifts the Soret peak to longer wavelengths with increased intensities, 414 nm (149.3 mM−1cm−1) and 420 nm (125.7 mM−1cm−1), respectively (Fig. 9A and Table S1). The Q bands of Vc H-NOX-Im and Vc H-NOX-CN− complexes also shift to longer wavelengths, 534 nm and 538 nm, respectively, with similar intensities (Table S1). Charge-transfer band is not observable for either complex. The wavelength and high intensities of the Soret bands and the absence of a charge-transfer band indicate that the coordination of imidazole or cyanide to Fe(III) Vc H-NOX converts heme to fully low-spin state. Compared to imidazole and cyanide, the binding of fluoride and azide to Fe(III) Vc H-NOX is much weaker. In the presence of > 200 mM fluoride or azide, the Soret peak shifts to shorter wavelengths, 400 nm (117.3 mM−1cm−1) and 394 nm (109.3 mM−1cm−1), respectively (Fig. 9A and Table S1). The Soret peak of Vc H-NOX-N3− complex is quite broad. Compared to that of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, the Q bands of Vc H-NOX-F− and Vc H-NOX-N3− complexes shift to longer wavelengths, 516 nm and 504 nm, respectively (Fig. 9A). Similar to unliganded Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, these two complexes show charge-transfer bands at 604 nm and 628 nm, respectively (Fig. 9A and Table S1). The wavelengths of Soret peaks and the presence of charge-transfer bands clearly indicate high-spin hemes in Vc H-NOX-F− and Vc H-NOX-N3− complexes. The spin state of Vc H-NOX-N3− complex is different from the low-spin state observed in Mb-N3− complex (23).

Figure 9.

Electronic absorption and MCD spectra of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its complexes with CN−, Im, F− and N3−. Electronic spectra (A) and MCD spectra (B) of ~ 5 μM Fe (III) Vc H-NOX and in the presence of 1.4 mM CN−, 200 mM Im, 500 mM F− and 200 mM N3−. The MCD spectra in region 500 – 700 nm was smoothed using the program came with the instrument. (C) NIR MCD spectra of ~85 μM Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and in the presence of 200 mM Im or 5.5 mM CN−. The samples for NIR MCD were in 20 mM HEPES with 50 mM NaCl buffer prepared in D2O. Spectra in Panels A to C are represented with the same set of colors: black, Fe(III) Vc H-NOX; red, Vc H-NOX-Im; blue, Vc H-NOX-N3−; green, Vc H-NOX-CN−; magenta, Vc H-NOX-F−.

As its electronic absorption spectrum, the MCD spectrum of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX also indicates predominantly high-spin heme as revealed by the presence of a charge-transfer band between 650 – 690 nm (Fig. 9B and Table S1). Compared to that of unliganded Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, the MCD spectra of complexes Vc H-NOX-Im and Vc H-NOX-CN− exhibit significantly stronger Soret bands (Fig. 9B), and Q bands are observed at longer wavelengths with stronger intensities, 582 nm (-19.5 M−1cm−1T−1) and at 578 nm (-26.6 M−1cm−1T−1) for Vc H-NOX-Im and Vc H-NOX-CN−, respectively (Fig. 9B and Table S1). Complex Vc H-NOX-Im also exhibits a peak of 8.1 M−1cm−1T−1 at 556 nm (Fig. 9B). The relative intensities of the Soret and Q bands between the Im and CN− complexes of Vc H-NOX are similar to that between the Im and CN− complexes of metMb (24, 25). No charge-transfer band in 600 – 700 nm range is observed, confirming the low-spin state of heme in these two complexes (Fig. 9B).

The MCD spectrum of Vc H-NOX-F− complex exhibits Soret and Q bands at similar wavelengths to those of unliganded Vc H-NOX but with smaller intensities and a charge-transfer band is present in the region 610 – 660 nm (Fig. 9B and Table S1), consistent with a high-spin heme as indicated by its electronic absorption spectrum. The Soret MCD signal of Vc H-NOX-N3− complex is significantly smaller compared to those of Vc H-NOX and its other complexes (Fig. 9B). This is different from metMb-N3− complex, whose MCD exhibits a Soret band slightly smaller than those of its Im and CN− complexes (24, 25). The MCD of Vc H-NOX-N3− complex exhibits a strong Q band at the shortest wavelength among Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its complexes, −24.0 M−1cm−1T−1 at 554 nm and the strongest charge-transfer band between 630 – 680 nm (Fig. 9B and Table S1). These MCD features are in sharp contrast to those of metMb-N3− which exhibits a Q band comparable to that of metMb-Im and a very weak charge-transfer band at 647 nm (24) but overall similar to those in prostaglandin H synthase-N3− complex which possesses considerable amount of high-spin heme (26). The MCD of Vc H-NOX-N3− complex is therefore consistent with a high-spin heme.

The NIR MCD of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX exhibits two ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) bands, one at 1619 nm and the other at 1232 nm (Fig. 9C). Compared to those of Ns H-NOX (14), the MCD signals of Vc H-NOX are of significantly lower intensities (Table S1). Although electronic absorption spectrum, visible region MCD and EPR (see below) all indicates that the Fe(III) Vc H-NOX heme is largely high-spin, its NIR MCD is significantly different from that typical for a high-spin ferric heme such as in metMb (metMb-H2O), which exhibits a weak derivative shape MCD signal around 1150 nm (27, 28). Upon the binding with CN− and Im, intensities of the two NIR MCD bands increase significantly (Fig. 9C and Table S1), resulting in the NIR MCD spectra similar to that of Ns H-NOX (14). In the presence of Im, the NIR MCD of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im complex exhibits a LMCT at 1563 nm with a shoulder at 1355 nm (Fig. 9C). These features are typical for a bis-histidine low-spin ferric heme complex (27, 29–31). The overall similarity between the MCD of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its Im complex suggests that Fe(III) Vc H-NOX may contain ~25% low-spin heme due to the distal histidine coordination. Compared to that of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im complex, the LMCT band of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-CN− complex centers at a longer wavelength at 1594 nm with a shoulder at 1372 nm (Fig. 9C), consistent with that the NIR CT band for the CN−/histidine-ligated heme occurring at a wavelength of ~1600 nm (27).

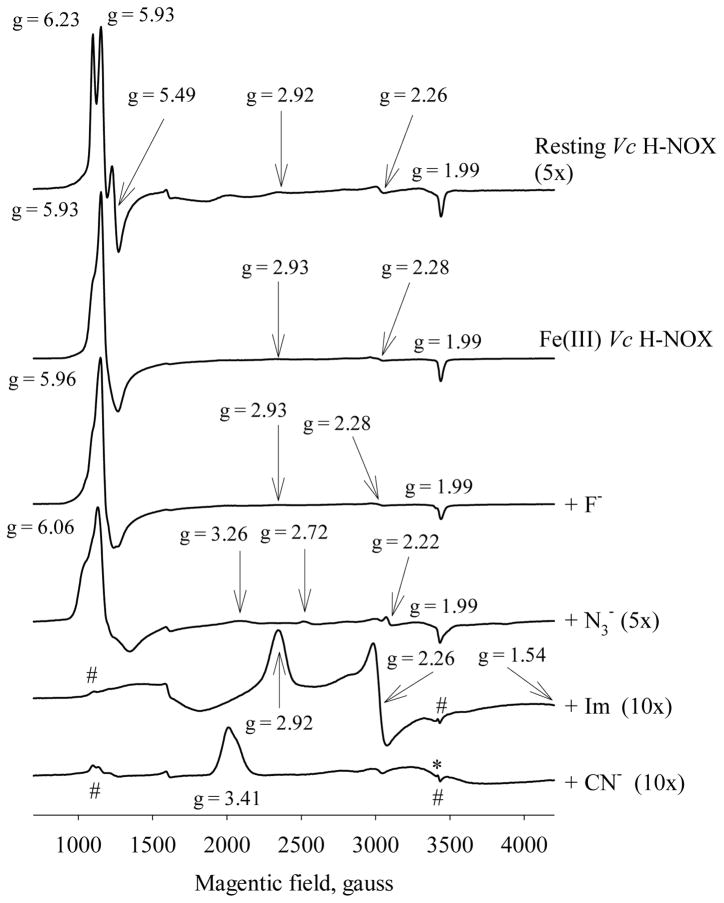

EPR characterization of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its complexes

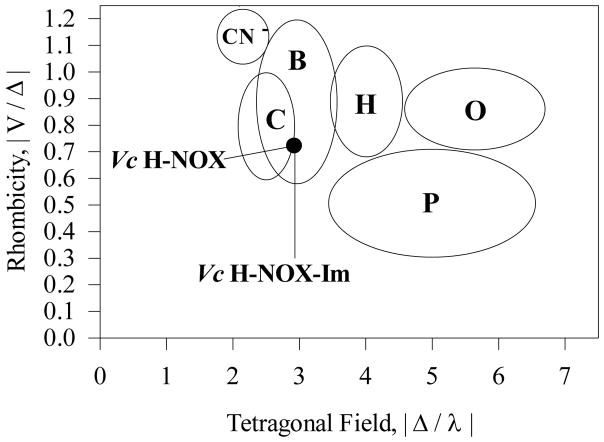

EPR signatures for both high-spin and low-spin ferric hemes are observed for the resting Vc H-NOX (Fig. 10), consistent with the electronic absorption and MCD data (data not shown). The high-spin signal is heterogeneous, containing both rhombic component, with gx = 6.23 and gy = 5.49, and axial component, with gx/gy = 5.93. The gz for both high-spin heme geometries is observed at 1.99 (Fig. 10). For the low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, signals at gmax = 2.92 and gmid = 2.26 are more visible (Fig. 10), and the third g component predicted to be at gmin = 1.50 is not visible for its broad linewidth. These low-spin signals are unlikely due to the ligation to heme by the Im used in Vc H-NOX purification since the [Im] in the resting Vc H-NOX after Im removal by desalting chromatography was much lower than its KD for Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, 4.2 mM, measured by titration (data not shown). The correlation between its heme rhombicity and the ligand tetragonal field strength of the low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX based on its g values puts it in Zone B of the “truth diagram” (Fig. 11) (15, 32). This indicates that the axial ligand in the low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX is likely a histidine (15, 32), as proposed for the low-spin Fe(III) Ns H-NOX (14) and suggested by the MCD of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX (Fig. 9C). However, His150, which is proposed as the axial ligand in the low-spin Fe(III) Ns H-NOX, is not conserved in Vc H-NOX. On the other hand, the “truth diagram” of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im superimposable with that of as isolated low- spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX (Fig. 11), suggesting that the axial ligand in the resting low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX is possibly still a histidine residue. In a structure of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX modeled against the crystal structure of Fe(II) Ns H-NOX, the closest histidine on the distal side of heme is His77, which is ~11 Å away from iron. If His77 does coordinate with heme in low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, reduction may cause some significant movement of His77. Similar connection of such drastic conformational rearrangements to the subsequent signal transduction is proposed for Ns H-NOX during its redox state change (14).

Figure 10.

EPR spectra of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX and its complexes. The spectra are obtained at 10 K. “Resting Vc H-NOX” is the purified Vc H-NOX without further treatment. “Fe(III) Vc H-NOX” is the ferricyanide oxidized Vc H-NOX. The various complexes were prepared using Fe(III) Vc H-NOX, by adding ligands to the following final concentrations: cyanide, 21 μM; imidazole, 196 mM; azide, 512 mM and fluoride, 794 mM. Some spectra are magnified with the factors specified in parentheses for easy comparison. The important g values of each spectrum are marked. “#” indicates the residual high spin signals in Im and CN− complexes and “*” indicates the possible gmid of the low spin heme in CN− complex.

Figure 11.

Truth diagram analysis of the low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX. Six zones, in mapping the correlation between the heme rhombicity and the axial ligand field strength of low-spin heme complexes, are labeled with various letters. Five zones contain the complexes with histidine as the proximal ligand but different distal ligands: cyanide (zone CN−), methionine (zone C), histidine (zone B), imidazolate/azide (zone H), and hydroxide/phenolate (zone O). Zone P contains proteins which have a cysteine thiolate proximal ligand. The position of the low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX is represented by a solid circle and is superimposed with that of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im complex.

After the resting Vc H-NOX was oxidized with ferricyanide, the rhombic component of the high-spin heme in Fe(III) Vc H-NOX decreases noticeably, now observed as a shoulder of EPR signal of the axial heme at g = 5.93 (Fig. 10). Concomitantly, the size of the axial EPR signal increases significantly. Two EPR features, gmax = 2.93 and gmid = 2.28, are also visible for the low-spin heme for the ferricyanide-treated Vc H-NOX (Fig. 10).

Formation of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im complex abolishes most of the high-spin heme signals, leading to a predominant low-spin heme with three principal g values at 2.92, 2.26 and 1.54 (Fig. 10), indicating the formation of a 6c bis-imidazole heme complex. The “truth diagram” of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im overlaps exactly with that of the resting low-spin Fe(III) Vc H-NOX (Fig. 11), indicating that the axial ligand field and the rhombicity of the heme in Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-Im complex are very similar to those in the resting low-spin Vc H-NOX (15, 32). Like EPR features of the Im complex, Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-CN− complex exhibits a EPR of predominant low-spin heme. On the other hand, only an abnormally large gmax value of 3.41 was observed, similar to that of metMb-CN− (33), indicating that the low-spin heme in Vc H-NOX-CN− complex is of a highly axial geometry (34). This type of heme has been observed in the CN− complex of many other hemoproteins (35–41). The values of the other two g components, gmid and gmin, are not determined due to the overlapping with the residual high-spin gz (Fig. 10) and being out of range of the data collection, respectively. The EPR signal of Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-CN− complex is of smaller amplitude compared to those of the Im complex. This is likely due to the increased anisotropy in g tensor (42).

The binding of F− to Fe(III) Vc H-NOX does not fully convert the portion of the low-spin heme in Fe(III) Vc H-NOX to high-spin, even at [F−] as high as 790 mM. This is indicated by the only partially split signal at g =1.99, which is due to I = ½ nucleus spin of 19F, and the visible low-spin signals at gmax = 2.93 and gmid = 2.28 (Fig. 10). Some rhombic high-spin heme geometry is still observable in the presence of high concentration of F−, as indicated by the shoulder of the signal at g = 5.96 (Fig. 10). In the presence of 512 mM N3−, the intensity of EPR of the high-spin heme decreases significantly, although still dominates the EPR spectrum, indicating N3− does not convert Fe(III) Vc H-NOX to low-spin state effectively, consistent with the electronic absorption and MCD data (Fig. 9A and B). This is different from that N3− completely converts metMb to low-spin state (23). The axial high-spin signal shifts slightly towards lower frequency to g = 6.06 (Fig. 10). The EPR signal of rhombic high-spin heme increases as suggested by the more noticeable shoulders around the axial high-spin signal (Fig. 10). Two sets of weak EPR signatures for low-spin heme were observed for Fe(III) Vc H-NOX-N3−. One set has g values similar to those of metMb-N3−: gmax = 2.72 and gmid = 2.22 (23, 33); the other set has a gmax = 3.26 for a heme geometry of much lower rhombicity.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms of gaseous ligand binding to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX could be summarized in Scheme 1 based on our spectroscopic and kinetic data (Table 1). CO binds Vc H-NOX in a reversible one-step process (A to F). NO, on the other hand, binds Vc H-NOX in multiple steps. Stoichiometric amount of NO binds to Vc H-NOX quickly and forms a 6c NO-Vc H-NOX-His complex (A to B), and the subsequent breakage of the proximal histidine coordination to iron leading to a 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex (B to E). In the presence of excess amount of NO, a second NO molecule binds to Vc H-NOX, presumably forming a transient quaternary complex (B to C), which quickly converts to a 5c Vc H-NOX-NO complex with likely the distal NO ligands released (C to D) similar to that found in sGC using 15NO/14NO and freeze quench EPR (8). When Fe(II) Vc H-NOX is reacted with O2, the equilibrium biases towards the reactants (A), however, autoxidation leading to Fe(III) Vc H-NOX appears to proceed slowly (G to H), without accumulation of the transient oxyferrous complex.

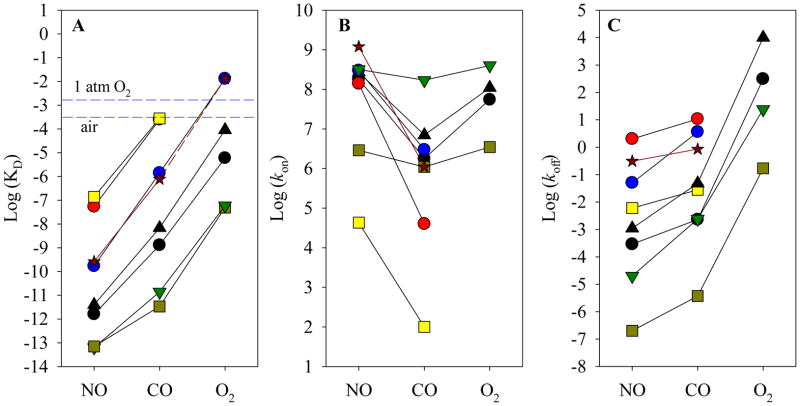

When affinities of NO and CO to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX (Table 1) are plotted versus ligand type, the line connecting the values of logKD(NO) and logKD(CO) is almost superimposable with that of Ns H-NOX and parallels those of sGC and many heme sensor proteins and PP(1-MeIm) heme model (5) (Fig. 12A). This clearly indicates that the selectivity of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX for gaseous ligands follows the same pattern as sGC and Ns H-NOX and is also consistent with the “sliding scale rule” hypothesis. Based on the “sliding scale rule”, affinity of O2 for Fe(II) Vc H-NOX can be predicted to be similar to that of Ns H-NOX, ~13 mM (Fig. 12A, dashed line & Table 1). In the plots of kinetic parameters versus ligand type, the line connecting logkon(NO) and logkon(CO) and the line connecting logkoff(NO) and logkoff(CO) approximately parallel those of sGC, Ns H-NOX and many other heme sensor proteins and heme model Fe(II)PP(1-MeIm) (5) (Fig. 12B and C).

Figure 12.

Relationship of logKD, logkon and logkoff of NO and CO for Fe(II) Vc H-NOX versus ligand type. The measured logarithm values of KD (A) and kon (B) and koff (C) of NO and CO to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX are plotted versus ligand type (dark red stars and solid dark red line). (A) The predicted logKD(O2) is connected to logKD(CO) by a dark red dashed line. Parameters measured for some other heme sensors and heme model Fe(II) PP (1-MeIm) are plotted for comparison and to show the large dynamic range of KD, kon and koff values modulated by the different heme binding environments: cyt c′ (yellow square); Ns H-NOX (blue circle); sGC (red circle); H64V sGC (black triangle); L16A cyt c′ (light green square); H61L leghemoglobin (Lb) (green triangle); Fe(II) PP (1-MeIm) (black dot). The values for these heme sensors can be found in reference (5) and the literatures cited therein.

With high affinities and multiple steps in NO binding and exclusion of O2 binding, the characteristics of gaseous ligand binding are overall quite similar among Vc H-NOX, sGC and Ns H-NOX. However, a few obvious differences exist in the bindings of NO and O2 to these three heme sensor proteins. One such difference is noticed in the binding of the second NO to these three proteins. In sGC, in the presence of 1:1 NO, the 6c NO-heme-His complex quickly converts to the 5c heme-NO complex with a Soret peak at 399 nm, which later oscillates between the 5c heme-NO complex and Fe(II) sGC (43). Such an oscillation phenomenon was not observed for Ns H-NOX in the presence of stoichiometric amount of NO and its 6c NO-heme-His complex appears to be stable (14). Similar to sGC, the 6c NO-heme-His complex in Vc H-NOX is not stable, as indicated by the Soret peak shift from 418 nm to 399 nm, which is majorly a 5c heme-NO complex as indicated by its EPR spectrum (Fig. 8B). However, unlike sGC, the conversion from the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex to the 5c heme-NO complex is very slowly. Moreover, no back conversion to Fe(II) Vc H-NOX was observed. In the presence of higher [NO], 2:1 ratio of NO versus sGC leads to the formation of the 5c heme-NO complex with a Soret peak at 399 nm, presumably with NO coordinating to the heme on its proximal side (5). In Ns H-NOX, however, similar 5c heme-NO complex is only observable in the presence of high [NO]. In the presence of 2-fold of NO, an alternate 6c heme-NO complex forms in Ns H-NOX with a Soret peak at 414 nm (14). In Vc H-NOX, in the presence of [NO] above the stoichiometric level, a 5c heme-NO complex forms readily with a Soret band at 398 nm. Similar to that in sGC, the rate of the 5c heme-NO complex formation in the presence of excess amount of NO is [NO]-dependent, suggesting NO binds to the proximal side of heme (8). However, the kinetics of the formation of this 398 nm 5c heme-NO complex in Vc H-NOX is different from that in sGC. In sGC, the formation rate of the 5c heme-NO complex is always linearly dependent on [NO], indicating that release of one NO molecule from the hypothetic quaternary complex intermediate is fast and not rate-limiting (8). In Vc H-NOX, the formation rates of the 5c heme-NO complex level off at high levels of [NO], suggesting that the formation of a quaternary complex intermediate (Scheme 1, C) becomes rate-limiting at high [NO], with a limiting rate of 720 s−1 (Fig. 6, inset). Rapid-freeze technique could be tried to trap this transient intermediate, which may accumulate to a detectable level at very high [NO].

As sGC and Ns H-NOX, Vc H-NOX does not show any appreciable association with O2 to form an observable oxyferrous heme-O2 complex under the atmospheric pressure. On the other hand, difference is observed for the subsequent autoxidation process. Ferrous sGC does not exhibit any noticeable autoxidation in the air and Fe(II) Ns H-NOX was observed to autoxidize with a very slow rate of ~ 0.05 hr−1 (14). On the other hand, mixing O2 with Fe(II) Vc H-NOX leads to a shift of Soret peak within minutes (Fig. 3). However, the transient oxyferrous Vc H-NOX-O2 intermediate was not detected, presumably due to a large koff(O2) constant out of the detection limit of our stopped-flow instrument. The observed spectral change is likely due to the autoxidation of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX as written in the following two equations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

The equilibrium of reaction (3) is biased toward the reactant side due to the large KD(O2). Autoxidation as in reaction (4) can be assumed to be irreversible, k-4 = 0. A Michaelis-Menten type kinetic relationship can therefore be written for the observed rate:

Since [O2] used in the experiment is much lower than the projected KD(O2), the equation above can be simplified as:

which explains the observed linear dependence of kobs on [O2] (Fig. 3B, inset). Overall, the autoxidation rate constant of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX-O2 to Fe(III) Vc H-NOX can be estimated as k4 = slope × KD(O2) = ~ 0.06 s−1 (Fig 3B). The autoxidation rate of Fe(II) Vc H-NOX is much faster than that of Ns H-NOX, 0.05 hr−1 (5, 14). This relatively fast autoxidation also explains why KD(O2) for Ns H-NOX are measureable using a high pressure cell and equilibrium titration, but not for Vc H-NOX.

Overall, the validity of “sliding scale rule” hypothesis for the binding of gaseous ligands to heme sensor proteins is supported again by our detailed characterization of the binding of NO, CO and O2 to Vc H-NOX. The variations between the affinities of a particular gaseous ligand to sGC, Ns H-NOX and Vc H-NOX and in the later phases of NO and O2 bindings to these proteins are likely determined by the subtle environmental differences around their heme prosthetic groups.

Although a crystallographic data is not yet available for Vc H-NOX, homology modeling against the structures of Ns H-NOX (9) or Tt H-NOX (13), especially for the heme pocket, indicate that the key structural elements in binding the heme: His105 (proximal heme ligand, sGC numbering), Tyr136, Ser138 and Arg140 (YXSXR motif) (7, 44) are well conserved. Tyr145, the H-bond donor that may contribute to preferential stabilization of O2 in Tt H-NOX, is replaced by Ala145 in Vc H-NOX (7, 13). The exclusion of O2 binding to Vc H-NOX and the relatively fast autoxidation are only partially due to lacking such an H-bond donor. Other factors, including the distal steric hindrance and proximal strain of the heme likely play even more important role in making the vertical up-shift of logKD values of all three gaseous ligands from those for the heme model. Compared to Ns H-NOX, the distal steric hindrance seems to be much less for Vc H-NOX with the distal bulky residue Trp74 in Ns H-NOX (or Phe74 in sGC) replaced by Leu74 in Vc H-NOX. Since the position of Vc H-NOX in “sliding scale plot” (Fig. 12) is almost superimposable to Ns H-NOX, the other factor(s), such as proximal constraints, may play a more dominant role in regulating the ligand affinity than distal steric hindrance in Vc H-NOX. Locating the structural component(s) that regulates the proximal constraints with crystallographic data for both wild type and specific amino acid mutant(s) should provide incisive information on this issue and is our ongoing effort.

It has been proposed that H-NOX domain in facultative aerobic bacteria, such as Vc H-NOX in Vibrio cholerae, serves as a sensing domain and signals a shift to growth in a low O2 environment (7). NO sensing may also play an important role in the pathology of Vibrio cholerae. On the other hand, the infection of Vibrio cholerae to human beings causes massive production of inflammatory mediators including reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) (45–47). The induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in this immunological response leads to a large amount of NO formation, serving as a bacterial killing agent in conjunction with the induction of myeloperoxidase biosynthesis to generate ROS (45–47). iNOS, itself can behave as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide or peroxynitrite synthase under uncoupled catalysis with limited supply of either the L-arginine substrate or the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin1 (48–50). Thus, these self-protective agent induced in the host will exert tremendous oxidative stress on Vibrio cholerae pathogen. Several key gene products for NO detoxification are induced in Vibrio cholerae including NO sensing and NO dioxygenase flavohemoglobins (47). Certain counter stress mechanism is induced by ROS such as H2O2 (47). Although the functional partner(s) for Vc H-NOX has not been identified, to deal with the substantial stress of NO and ROS from host defense requires efficient sensing mechanism for both NO and other ROS. In that aspect, Vc H-NOX may behave like Ns H-NOX (14), as a gaseous sensor or/and a redox sensor. Overall the selective binding of ferrous Vc H-NOX to NO may provide the pathogen a signaling pathway to respond to the environmental level of NO, which can be modulated by the immune response and iNOS activation of the host. This signaling pathway may therefore help the pathogen to survive the defense of the host and increase its virulence in the digestive tract where oxygen content is fairly low. The information of ligand bindings to ferric Vc H-NOX may also provide insights into the signaling pathway(s) for the survival of this pathogen under the possible redox states where Vc H-NOX exists in its ferric form. Therefore, our study on Vc H-NOX at both ferrous and ferric redox states should provide useful insights into the virulence of this human pathogen especially the mechanism for it to deal with the host defense to sustain its colonization in the gastrointestinal tract.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 HL 095820 to A.-L. T.

Abbreviation

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- CT

charge transfer

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- H-NOX proteins

heme-nitric oxide and oxygen binding

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- Im

imidazole

- LMCT

ligand-to-metal charge transfer

- MCD

magnetic circular dichroism

- Mb

myoglobin

- metMb

metmyoglobin

- NIR MCD

near infrared MCD

- Ns H-NOX

H-NOX protein found in Nostoc punctiforme

- sGC

soluble guanylyl cyclase

- SONO

sensor of NO

- Tt H-NOX

H-NOX protein found in Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis

- Vc H-NOX

H-NOX protein found in Vibrio cholerae

Footnotes

Berka, V., Liu, W., Wu, G. and Tsai, A.L., unpublished results.

Supporting Information: supporting materials are available at http://pubs.acs.org, including 1) Table S1. Absorption and MCD parameters of ferrous and ferric Vc H-NOX and their complexes and 2) Figure S1. Simulation of the NO binding to the 6c Vc H-NOX-NO complex.

References

- 1.Jain R, Chan MK. Mechanisms of ligand discrimination by heme proteins. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farhana A, Saini V, Kumar A, Lancaster JR, Jr, Steyn AJ. Environmental heme-based sensor proteins: implications for understanding bacterial pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1232–1245. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai AL, Martin E, Berka V, Olson JS. How do heme-protein sensors exclude oxygen? Lessons learned from cytochrome c’, Nostoc puntiforme heme nitric oxide/oxygen-binding domain, and soluble guanylyl cyclase. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1246–1263. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liebl U, Lambry JC, Vos MH. Primary processes in heme-based sensor proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:1684–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai AL, Berka V, Martin E, Olson JS. A “sliding scale rule” for selectivity among NO, CO, and O(2) by heme protein sensors. Biochemistry. 2012;51:172–186. doi: 10.1021/bi2015629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA. Structure and regulation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:533–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-050410-100030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon EM, Marletta MA. Ligand specificity of H-NOX domains: from sGC to bacterial NO sensors. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:892–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin E, Berka V, Sharina I, Tsai AL. Mechanism of binding of NO to soluble guanylyl cyclase: implication for the second NO binding to the heme proximal site. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2737–2746. doi: 10.1021/bi300105s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma X, Sayed N, Beuve A, van den Akker F. NO and CO differentially activate soluble guanylyl cyclase via a heme pivot-bend mechanism. EMBO J. 2007;26:578–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nioche P, Berka V, Vipond J, Minton N, Tsai AL, Raman CS. Femtomolar sensitivity of a NO sensor from Clostridium botulinum. Science. 2004;306:1550–1553. doi: 10.1126/science.1103596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boon EM, Marletta MA. Ligand discrimination in soluble guanylate cyclase and the H-NOX family of heme sensor proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karow DS, Pan D, Tran R, Pellicena P, Presley A, Mathies RA, Marletta MA. Spectroscopic characterization of the soluble guanylate cyclase-like heme domains from Vibrio cholerae and Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10203–10211. doi: 10.1021/bi049374l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellicena P, Karow DS, Boon EM, Marletta MA, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of an oxygen-binding heme domain related to soluble guanylate cyclases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12854–12859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405188101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai AL, Berka V, Martin F, Ma X, van den Akker F, Fabian M, Olson JS. Is Nostoc H-NOX a NO sensor or redox switch? Biochemistry. 2010;49:6587–6599. doi: 10.1021/bi1002234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai AL, Berka V, Chen PF, Palmer G. Characterization of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and its reaction with ligand by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32563–32571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonini E, Brunori M. Hemoglobin and Myoglobin in Their Reactions with Ligands. Vol. 21. North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pond AE, Roach MP, Thomas MR, Boxer SG, Dawson JH. The H93G myoglobin cavity mutant as a versatile template for modeling heme proteins: ferrous, ferric, and ferryl mixed-ligand complexes with imidazole in the cavity. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:6061–6066. doi: 10.1021/ic0007198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson JS. Stopped-flow, rapid mixing measurements of ligand binding to hemoglobin and red cells. Methods Enzymol. 1981;76:631–651. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)76148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kharitonov VG, Sharma VS, Magde D, Koesling D. Kinetics of nitric oxide dissociation from five- and six-coordinate nitrosyl hemes and heme proteins, including soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6814–6818. doi: 10.1021/bi970201o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derbyshire ER, Gunn A, Ibrahim M, Spiro TG, Britt RD, Marletta MA. Characterization of two different five-coordinate soluble guanylate cyclase ferrous-nitrosyl complexes. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3892–3899. doi: 10.1021/bi7022943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunn A, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA, Britt RD. Conformationally distinct five-coordinate heme-NO complexes of soluble guanylate cyclase elucidated by multifrequency electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) Biochemistry. 2012;51:8384–8390. doi: 10.1021/bi300831m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli C, Innes JB, Hirsh DJ, Brudvig GW. Effects of dipole-dipole interactions on microwave progressive power saturation of radicals in proteins. J Magn Reson B. 1996;110:284–287. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurus R, Bogumil R, Nguyen NT, Mauk AG, Brayer G. Structural and spectroscopic studies of azide complexes of horse heart myoglobin and the His-64-->Thr variant. Biochem J. 1998;332(Pt 1):67–74. doi: 10.1042/bj3320067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatano M, Nozawa T. Magnetic circular dichroism approach to hemoprotein analyses. Adv Biophys. 1978;11:95–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kajiyoshi M, Anan FK. Conformation of biological macromolecules. Circular dichroism and magnetic circular dichroism studies of metmyoglobin and its derivatives. J Biochem. 1975;78:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a130986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai AL, Kulmacz RJ, Wang JS, Wang Y, Van Wart HE, Palmer G. Heme coordination of prostaglandin H synthase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8554–8563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheesman MR, Greenwood C, Thomson AJ. Magentic Circular Dichroism of Hemoproteins. In: Sykes AG, editor. Advances in Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press; 1991. pp. 201–255. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nozawa T, Yamamoto T, Hatano M. Infrared magnetic circular dichroism of myoglobin derivatives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;427:28–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(76)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigby SE, Moore GR, Gray JC, Gadsby PM, George SJ, Thomson AJ. N.m.r., e.p.r. and magnetic-c.d. studies of cytochrome f. Identity of the haem axial ligands. Biochem J. 1988;256:571–577. doi: 10.1042/bj2560571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gadsby PM, Peterson J, Foote N, Greenwood C, Thomson AJ. Identification of the ligand-exchange process in the alkaline transition of horse heart cytochrome c. Biochem J. 1987;246:43–54. doi: 10.1042/bj2460043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson JH, Dooley DM. Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy of Iron Porphyrins and Heme Proteins. In: Lever ABP, Gray HB, editors. Iron Porphyrins, Part III. VCH Publishers, Inc; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blumberg WE, Peisach J. Probes and Structure and Function of Macromolecules and Membranes. Vol. 2. Academic Press; New York: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hori H. Analysis of the principal g-tensors in single crystals of ferrimyoglobin complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;251:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(71)90106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer G. The electron paramagnetic resonance of metalloproteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 1985;13:548–560. doi: 10.1042/bst0130548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadsby PMA, Thomson AJ. Assignment of the axial ligands of ferric ion in low-spin hemoproteins by near-infrared magnetic circular dichroism and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5003–5011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dou Y, Admiraal SJ, Ikeda-Saito M, Krzywda S, Wilkinson AJ, Li T, Olson JS, Prince RC, Pickering IJ, George GN. Alteration of axial coordination by protein engineering in myoglobin. Bisimidazole ligation in the His64-->Val/Val68-->His double mutant. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15993–16001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.15993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schunemann V, Trautwein AX, Illerhaus J, Haehnel W. Mossbauer and electron paramagnetic resonance studies of the cytochrome bf complex. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8981–8991. doi: 10.1021/bi990080n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friden H, Cheesman MR, Hederstedt L, Andersson KK, Thomson AJ. Low temperature EPR and MCD studies on cytochrome b-558 of the Bacillus subtilis succinate: quinone oxidoreductase indicate bis-histidine coordination of the heme iron. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1041:207–215. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90067-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hederstedt L, Andersson KK. Electron-paramagnetic-resonance spectroscopy of Bacillus subtilis cytochrome b558 in Escherichia coli membranes and in succinate dehydrogenase complex from Bacillus subtilis membranes. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:735–739. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.2.735-739.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter KR, Tsai A, Palmer G. The coordination environment of mitochondrial cytochromes b. FEBS Lett. 1981;132:243–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)81170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai AL, Palmer G. Purification and characterization of highly purified cytochrome b from complex III of Baker’s yeast. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1982;681:484–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(82)90191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang JS, Tsai AL, Heldt J, Palmer G, Van Wart HE. Temperature- and pH-dependent changes in the coordination sphere of the heme c group in the model peroxidase N alpha-acetyl microperoxidase-8. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15310–15318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai AL, Berka V, Sharina I, Martin E. Dynamic ligand exchange in soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC): implications for sGC regulation and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43182–43192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iyer LM, Anantharaman V, Aravind L. Ancient conserved domains shared by animal soluble guanylyl cyclases and bacterial signaling proteins. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qadri F, Raqib R, Ahmed F, Rahman T, Wenneras C, Das SK, Alam NH, Mathan MM, Svennerholm AM. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators in children and adults infected with Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:221–229. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.221-229.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janoff EN, Hayakawa H, Taylor DN, Fasching CE, Kenner JR, Jaimes E, Raij L. Nitric oxide production during Vibrio cholerae infection. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G1160–1167. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stern AM, Hay AJ, Liu Z, Desland FA, Zhang J, Zhong Z, Zhu J. The NorR regulon is critical for Vibrio cholerae resistance to nitric oxide and sustained colonization of the intestines. MBio. 2012;3:e00013–00012. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00013-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide synthase generates superoxide and nitric oxide in arginine-depleted cells leading to peroxynitrite-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6770–6774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia Y, Roman LJ, Masters BS, Zweier JL. Inducible nitric-oxide synthase generates superoxide from the reductase domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22635–22639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffith OW, Stuehr DJ. Nitric oxide synthases: properties and catalytic mechanism. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:707–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gray MO, Karliner JS, Mochly-Rosen D. A selective epsilon-protein kinase C antagonist inhibits protection of cardiac myocytes from hypoxia-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30945–30951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.