Abstract

Sea anemone neurotoxins are peptides that interact with Na+ and K+ channels, resulting in specific alterations on their functions. Some of these neurotoxins (1ROO, 1BGK, 2K9E, 1BEI) are important for the treatment of about 80 autoimmune disorders because of their specificity for Kv1.3 channel. The aim of this study was to identify the common residues among these neurotoxins by computational methods, and establish whether there is a pattern useful for the future generation of a treatment for autoimmune diseases. Our results showed eight new key common residues between the studied neurotoxins interacting with a histidine ring and the selectivity filter of the receptor, thus showing a possible pattern of interaction. This knowledge may serve as an input for the design of more promising drugs for autoimmune treatments.

Keywords: neurotoxins, potassium channel, Kv1.3, computational methods, autoimmune diseases

Highlights

The structural similarity between the neurotoxins is a property that enables effective blockade of the channel.

The residues Met21–Lys22–Tyr23–Gln24–Lys25–Ser26–Tyr26–Phe27 are the most common ones among the neurotoxins.

The pattern of the interaction between the neurotoxins and the Kv1.3 channel could be represented by the regular expression X(5)–[FT]–[KI]–X(3)–R–X(4)–Q–X(4)–M–K–Y–Q–K–[SY]–F.

Our results validate the significance of the histidine ring of the channel as significant for the generation of a stable bonding in the interactions of the channel with neurotoxins 1ROO, BGK, 2K9E, and 1BEI.

Introduction

More than 125 million people worldwide are affected by about 80 different autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis,1,2 autoimmune encephalomyelitis,3–5 and myasthenia gravis.4 Recent studies showed that most treatments cause multiple secondary effects like exacerbation of autoimmune response, generation of new autoimmune disorders, and others.4,6 Autoimmune diseases are caused by an alteration of the immune response, where T or B cells are activated in the absence of an infection or any other cernible cause.7

Like many other marine organisms, sea anemones have a therapeutic potential because of the bioactive compounds found on their venom.8,9 Although these sessile invertebrates primarily use a potent neurotoxin to defend themselves from predators, previous reports have shown that these compounds are useful for autoimmune response treatment because of their specificity for kv channels, which regulate the function of T and B memory cells.6,10,11 Sea anemone neurotoxins are polypeptides with molecular weights ranging from 3,000 to 6,500 Da, and previous reports support their capacity to block K+ and Na+ channels.6,12–17 The neurotoxins ShK and BgK, derived from Stichodactyla helianthus and Bunodosoma granulifera, respectively, act on more than six binding sites of the Kv1.3 channel.18 It is important to note that the study of the conformational properties could provide an opportunity to deduce the structural determinants of each mode of action.12,13

Potassium channels regulate numerous cellular processes, and alteration of this channel interrupts the flow-dependent signaling through the ionic membrane.2,4,5 Among the great variety of K+ channels, those mediated by electric induction are so-called potassium voltage-gated (Kv) channels, which control electrical excitability and plasmatic membrane potential.12,19,20 In general, these kv channels are subdivided into six subfamilies (Kv1–Kv6), while Kv1 channel is subdivided into 10 subunits (Kv1.1–Kv1.10).12,13,21,22 Kv1.3 channels are widely found at macrophages, platelets, osteoclasts, brain, and B lymphocytes, but they only control membrane potential at T lymphocytes, mostly at the T effector memory (TEM) cells.23 Modifications of ion flux in the Kv1.3 channel alter the proliferation of T-cell, thus affecting the autoimmune response.1,3,24,25 Even though the importance of the Kv1.3 channel for the development of better treatments for autoimmune diseases is widely known, its structure has not been resolved by experimental techniques. In this context, it is possible to assess its structure by computational methods like homology modeling to have more functional data for the rational drug design.26,27 The computational methods used here led us to have an approximation of a rational drug design for the treatment of autoimmune diseases because of its exact and fast analysis,28–30 when compared to the complexity and high cost of the experimental procedures, and low information availability.28,31

Although the high affinity of ShK and BgK for Kv1.3 channel by experimental and some computational methods was previously reported,9,10,32,33 these results are barely agreeing in respect to some binding sites that could be useful for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Previous studies have demonstrated the existence of some important residues, such as Lys25, Tyr26, Ser23, Arg11, Lys22, that probably have a key role on the conformation of the complex between the sea anemone neurotoxins and the Kv1.3 channel.23,24,34–37 Despite the information available of the key residues, there is no information available about the common residues between the neurotoxins from B. granulifera and S. helianthus, which interact with the Kv1.3 channel; this information would be useful to observe whether there is a pattern valuable for the future generation of a treatment for the autoimmune diseases, because current treatments generate multiple side effects. For this reason, the aim of this study is to identify by computational methods the common residues among these neurotoxins, and establish if there is a useful pattern for a future treatment for autoimmune diseases with less multiple side effects.

Computational Procedures

This study assessed four sea anemone neurotoxins from B. granulifera and S. helianthus. The neurotoxin crystalline structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession codes: 1BGK derived from B. granulifera;33 1ROO the pure ShK toxin, which belongs to S. helianthus;18 1BEI that corresponds to the mutated ShK-Dap;10 and 2K9E, the potent selective ShK-192 modified from ShK–170.32 These neurotoxins were chosen because of lack of structural information reported about their interaction with the Kv1.3 channel. The Kv1.3 channel was modeled by Smith and collaborators,24 who assessed a model of the pore and vestibule of the Kv1.3 channel based on the crystallographic structure of the K+ channel from Streptomyces lividans (Kcsa)26 and subsequently, modeled with MODELLER software.38 This Kv1.3 channel has been useful to determine important interactions that were subsequently verified in animal models with positive result, which indicates it is a trustable computational model.8,39

Molecular docking

The complexes of each neurotoxin with the Kv1.3 channel were generated by docking methods using the fully automatic ClusPro protein—protein docking server version 2.0 that uses PIPER, a fast Fourier transform (FFT)-based protein docking program.40 The results were generated based on the correlation technique used by ClusPro 2.0, establishing the receptor (Kv1.3) on a fixed grid taking into account its transmembrane protein (divided into squares of 3 Å) and the ligand (1BGK, 1ROO, 1BEI, and 2K9E) on a movable grid.41–43 The score of the potential solutions generated by the server group included all conformations, whose solutions were at the range of 10 Å with respect to the RSMD of the original structure.43 Macromolecular complexes were obtained from the docking performed with LIGPLOT v.5.0.4. software.44 The final complexes were visualized using PyMOL v0.9845 and MOE 2009.10.46

Neurotoxin structural alignment

A structural alignment was performed with the main chain from the four neurotoxins, through the MOE v.2010.10 software,46 and the RSMD was calculated to find the relation between form and function.

Results and Discussion

In terms of primary structure, the neurotoxins have eight cysteine residues linked to form four disulfide bridges. The sequences show that the neurotoxins are homologous; this conservation and similar molecular organization indicate that there are certain conformational characteristics that could be involved with the mode action. The secondary structure shows predominantly beta-sheets. Most of the invariant residues are localized in the vicinity of the disulfide bridges. The folding pattern of the polypeptide chain has been elucidated by X-ray crystallography.

The information retrieved from the structural alignment and molecular docking revealed that the residues Met21–Lys22–Tyr23–Gln24–Lys25–Ser26/Tyr26–Phe27 conformed a key motive. The pattern or key motive, which is considered essential for the interaction with the Kv1.3 channel, can be represented by the pattern: X(5)–[FT]–[KI]–X(3)–R—X(4)–Q–X(4)–M–K–Y–Q–K–[SY]–F.44,47 To assess the structural feature of neurotoxins, we performed alignment before and after docking analyses, which revealed the importance of a similar structure among the neurotoxins, to generate the interaction with the Kv1.3 channel.

Molecular docking

Based on previous experimental and computational methods, we found a high affinity of the following residues with the channel: the neurotoxin 1BEI interacted with Arg11 and Dnp22, which was replaced from a Lys22 to generate a higher affinity; meanwhile the neurotoxins 2K9E and 1ROO interacted with Lys22, indicating its importance to the blockade of Kv1.3 channel pore. 1ROO also interacted with Tyr23 and Phe27; and 1BGK, which belonged to the sea anemone B. granulifera, interacted through Phe6, Lys7, Gln24, Lys25, and Tyr26. Several different studies have reported the biological role of these residues in the interaction.6,9–12,21,32,34,35,48 Furthermore, our results pointed new residues that might be involved at the interaction site: 1BEI (Thr6, Pro8, Ser10, Gln16, His19, Ser20, Tyr23, and Phe27), 2K9E (Ile7, Gln16, and Phe27), and 1ROO (Phe15, Met21, Ser26, Arg29; Table 1).

Table 1.

Results from the interactions between 1BEI, 2K9E, 1ROO, and 1BGK neurotoxins and the Kv1.3 channel. Interacting residues are shown (receptor and ligands): the atoms involved at each interaction, the type of interaction (H: H-bond, NB: non-bonding), and the distance between the interactions.

| CHANNEL KV1.3 | 1BEI | 2K9E | 1ROO | 1BGK | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESIDUE | ATOM | TYPE OF INTERACTION | RESIDUE | ATOM | DISTANCE | RESIDUE | ATOM | DISTANCE | RESIDUE | ATOM | DISTANCE | RESIDUE | ATOM |

| E/NE | |||||||||||||

| ASP153 | CB | NB | Ser20 | CB | 3.74 | NLE21 | CD | 3.79 | Phe6 | CD2 | |||

| C | NB | DNP22 | CB | 3.68 | |||||||||

| CA | NB | Ser20 | CB | 3.16 | NLE21 | CD | 3.56 | Ser26 | CB | 3.55 | Phe6 | CZ | |

| O | H | DNP22 | NG | 2.57 | Tyr26 | OH | |||||||

| ASP345 | CA | NB | Pro8 | CG | 3.60 | Met21 | CG | 2.58 | Gln24 | CG | |||

| O | H | Ser10 | OG | 3.14 | Gln16 | NE2 | 2.90 | ||||||

| OD1 | H | Gln16 | NE2 | 2.63 | |||||||||

| ASP57 | CA | NB | Tyr27 | CE2 | 3.75 | LyS22 | CG | 3.31 | Tyr23 | CE1 | 3.19 | ||

| CB | NB | Phe27 | CE2 | 3.30 | LyS22 | CD | 3.58 | TyR23 | CE1 | 3.51 | |||

| C | NB | PHE27 | CZ | 3.82 | Tyr23 | CE1 | 3.88 | ||||||

| GLY344 | CA | NB | Arg11 | CD | 2.87 | Lys22 | CE | 3.69 | Lys25 | CG | |||

| C | NB | Arg11 | CD | 2.96 | Met21 | CB | 2.98 | Gln24 | CG | ||||

| GLY56 | CA | NB | Lys22 | CG | 2.88 | ||||||||

| C | NB | Tyr23 | CE2 | 3.61 | Lys22 | CG | 3.27 | Lys22 | CG | 3.51 | |||

| O | H | Gln24 | N | ||||||||||

| HIS155 | CE1 | NB | Phe27 | CZ | 2.89 | Lys22 | CD | 3.01 | Phe27 | CZ | 2.39 | Tyr26 | CZ |

| CE1 | NB | DNP22 | CB | 3.33 | |||||||||

| HIS251 | CE1 | NB | His19 | CB | 3.47 | NLE21 | CD | 3.79 | Arg9 | CZ | 3.78 | Phe6 | CD2 |

| NE2 | H | Lys7 | N | ||||||||||

| SER34 | CB | NB | Thr6 | C | 3.72 | Phe27 | CE2 | 2.96 | |||||

| CB | NB | Ile7 | CD1 | 3.26 | |||||||||

| CA | NB | Ile7 | CD1 | 3.20 | Phe15 | CE2 | 3.37 | ||||||

| TYR151 | O | H | Gln16 | NE2 | 3.18 | ||||||||

| O | H | Arg11 | NH2 | 2.45 | |||||||||

| C | NB | Lys22 | CE | 3.86 | LS25 | CD | |||||||

| CB | NB | Phe6 | CE2 | ||||||||||

| C | H | Phe6 | CE2 | ||||||||||

| O | H | Lys25 | NZ | ||||||||||

| TYR343 | C | NB | Arg11 | CD | 3.70 | Lys22 | CE | 3.68 | Lys25 | C | |||

| O | H | Arg11 | NH1 | 2.35 | Lys22 | NZ | 3.07 | ||||||

Note: The Dnp22 residue corresponds to 3-amino-alanine (C3H9 N2O2) whose side chain consists of a group CH2-NH3+ and corresponds to a modification at position 22 of the native ShK neurotoxin where it replaced an Lys by a Dpn; the Nle21 residue corresponds to norleucine (C6H13 NO2) with an aliphatic side chain, which consists of a group (CH2)3-CH3, and corresponds to a modification of the native ShK neurotoxin at position 21, where an Met was replaced by an NLE.

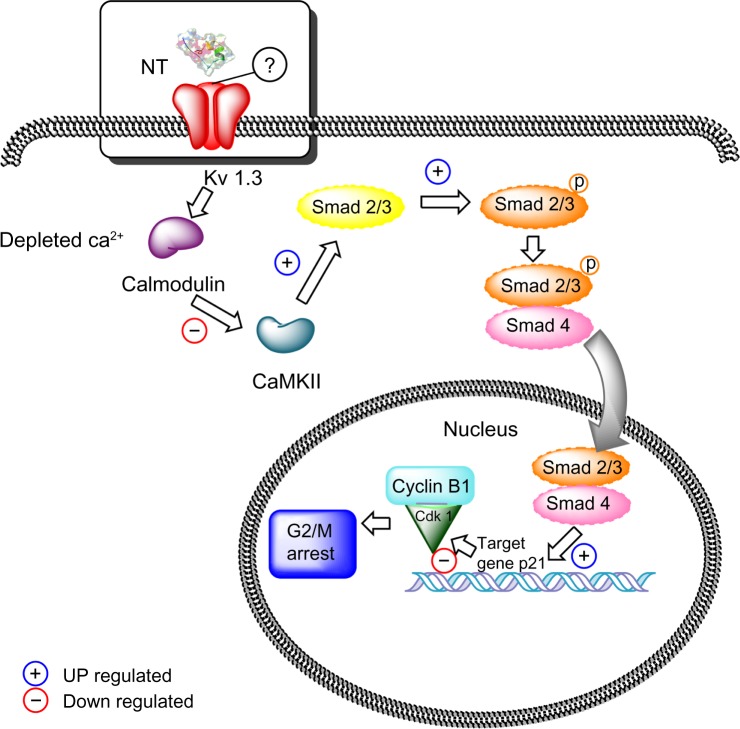

The bonding, attraction, or repulsion; Van der Waal’s energies; and the atomic contact energy for the macromolecular complexes labeled between the neurotoxins (1BEI, 1BGK, 1ROO, and 2K9E) and the Kv1.3 channel are shown in Table 2. The analysis of the interaction between the neurotoxins and the kv.13 channel shows the insertion of residues at the pore blocking the K+ ion flux through the channel (Fig. 1). This result agreed with a previous study reporting the selectivity filter of the Kv.13 conforms, probably by interacting with TVGYGD at the positions 444–449.49

Table 2.

Energies generated in the docked complex.

| ENERGY | 1BEI | 2K9E | 1ROO | 1BGK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glob | −49.16 | −60.33 | −35.61 | −46.88 |

| aVdW | −29.11 | −32.70 | −29.28 | −36.12 |

| rVdW | 7.64 | 13.45 | 17.23 | 20.65 |

| ACE | −2.76 | −6.26 | −0.82 | −0.58 |

Abbreviations: Glob, global binding energy; aVdW, attraction Van der Walls energy; rVdW, repulsive Van der Walls energy; ACE, atomic contact energy.

Figure 1.

Representation of the Kv1.3 channel with the key residues identified as balls and sticks visualized with MOE2009.10. Tyr343, Gly344, Tyr151, Gly56, Asp345, Asp153, and Asp57 with the histidine ring conform the key residues of the receptor that interact with neurotoxins.

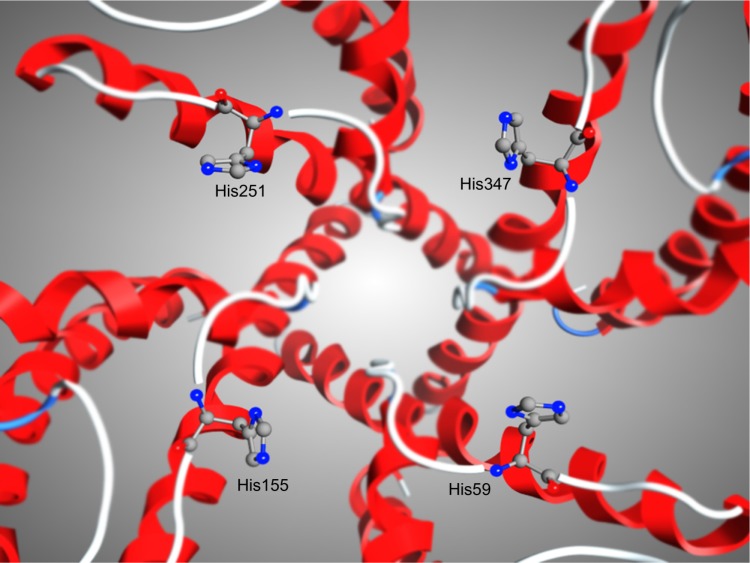

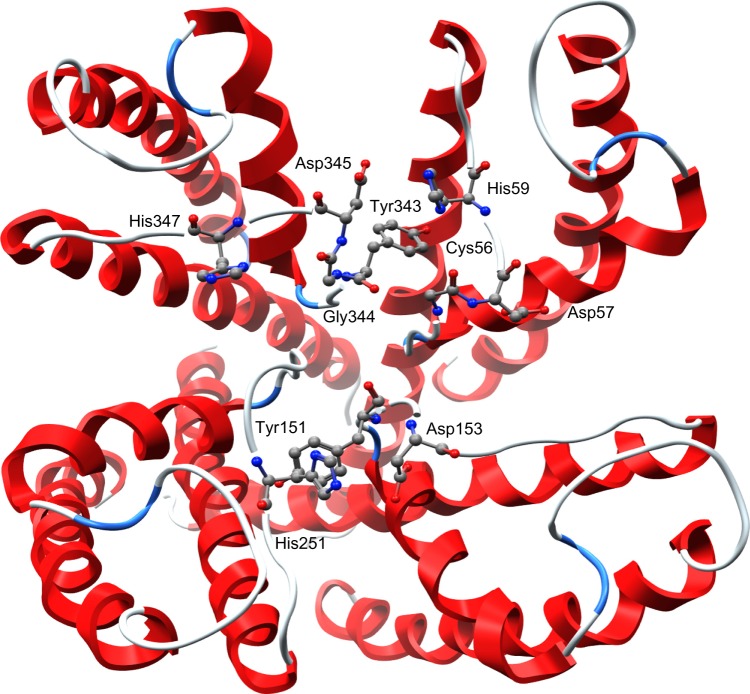

In accordance with previous studies, our results indicated that Asp376, Asp386, and Lys411 are key residues of the channel that conform this interaction (11; 14). For the channel Kv1.3, the interacting residues are Tyr343, Gly344, Tyr151, Gly56, Asp345, Asp153, and Asp57 (Fig. 1). In addition, we found that Kv1.3 channel had a unique histidine ring (3 let code HIS) located at the exterior entrance of the ion flux conduction, as previously reported.10,23 This ring is composed of His59, His155, His251, and His347 (Fig. 2), and may play an essential role promoting the interaction between 1BEI, 1ROO, 2K93, and 1BGK with the Kv1.3 channel. It is thought that the histidine ring has a major responsibility at the interaction with the neurotoxins, as it increases the affinity for the Kv1.3 channel,10 possibly because of its ability to form hydrogen bonds, ionic potential, flexibility, and polarity.

Figure 2.

Representation of the histidine ring at the entrance of the Kv1.3 channel visualized with MOE2009.10. The histidine ring is composed of His59, His155, His251, and His347, and is unique to Kv1.3 channel. The affinity that the neurotoxins presented to this ring suggests that the selectivity to the channel might be caused by this ring.

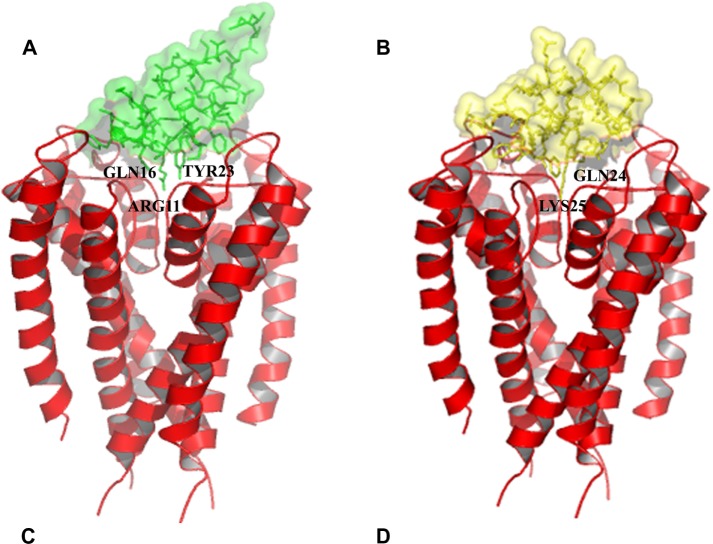

Some residues revealed a possible blockade of both ion flux through the channel and the selectivity filter. The results shown in Table 1 demonstrated that Lys played a fundamental role in the interaction with the Kv1.3 channel.50 This is probably because of its (i) flexible side chain that enters into the channel pore, thus probably blocking ion flux (Fig. 3), and (ii) hydrogen bonding potential with Tyr343 and His251 that enabled a stable bonding. Previous studies have shown that Lys is highly conserved among the neurotoxins 2K9E, 1ROO and 1BGK (Table 1), particularly at positions 7, 22 and 25.6,10,23,32–36 Other important residues in the interaction are Gln16, Gln24, and Met21. These residues are highly flexible and potential H-bond donors35; this characteristic, along with the presence of a long aliphatic chain that goes into the channel pore (Fig. 3), enabled the interaction with the channel, as does the Lys (Table 1).

Figure 3.

3D-surface representation, visualized by PYMOL v0.98, of the results of the molecular docking between neurotoxins studied and the Kv1.3 channel, which shows the channel pore blocked by four neurotoxins. (A) 1BEI (green) presets Arg11, Gln16, and Tyr2 blocking the channel pore. (B) 1BGK (yellow) shows a Gln24 at the entrance of the pore and the long aliphatic chain of Lys25 blocking ion flux as well. (C) 1ROO (blue) shows Met21 and Lys22. (D) 2K9E (violet) reveals a Lys22 and a Gln16 blocking as well as that the pore inhibits the correct function and proliferation of the T-cell.

The residues Phe (6, 15, and 27), Tyr26, and Tyr23 interacted with the receptor through His155, Asp153, Ser34, and Asp57 residues (Table 1). Interestingly, these residues presented moderate flexibility on Phe and Tyr residues from neurotoxins; in contrast, Lys did not present this property, though it enabled the interaction with the Kv1.3 channel. Also a Van der Waals-type interaction between Phe6/Asp153, Tyr23/Asp57, Tyr23/Gly56, Phe27/His155, Phe6/His252, Phe27/Ser34, and Thr6/Ser34 was observed. On the other hand, Tyr26 established hydrogen bonds with the O of Asp153, thus creating some stability in the complex, and likewise Ser10 established an interaction with the O of Asp345 forming a hydrogen bond (Table 1). Recently, Tyr at the positions 20–23 was reported as relevant for the generation of the complex NT/Kv1.3.6,23,33,35,36 In addition, it was observed that TYR at the position 26 generated a non-bonding interaction with Asp153.

Structural alignment

According to our results, there were conserved positions of the residues among 21 till 27 at the interaction area of the neurotoxin. It is possible to find a functional patter located in this region, but there is no information about the importance of preserving the physical—chemical properties of the neurotoxins to maintain the interaction. Previous studies performed on mutations at Lys22 and Met21 residues, replaced by Dpn22 and Nle21, respectively,10 did not reveal whether it is necessary to maintain the physical—chemical properties to maintain its biological effect at the system. Based on this observation, a structural alignment was further performed in the present study. In this context, the RMSD value was selected as a quantitative indicator of structure variability for alternative conformation within the same molecule. The visual analysis of multiple structural alignments allowed us to identify that 1BEI, 1BGK, 1ROO, and 2K9E residues had structural similarities (RMSD ≤ 2.380 Å; Figure 4).

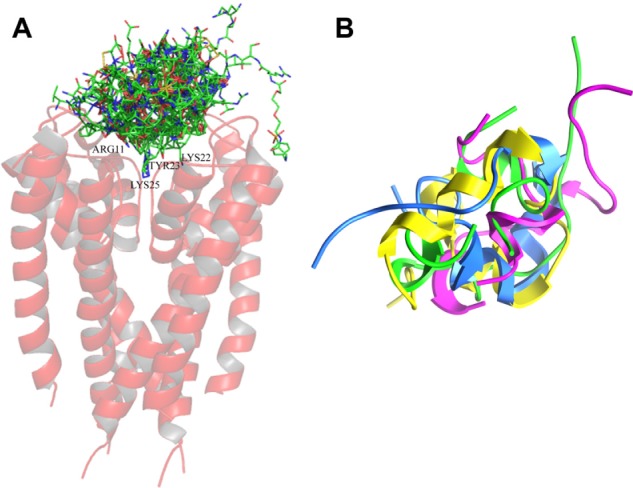

Figure 4.

Structural alignment of the neurotoxins performed with MOE2009.10. (a) Representation of the backbones in 3D (1) 1BEI, (2) 1BGK, (3) 1ROO, and (4) 2K9E showed a structural similarity. The relation between the align structures showed a satisfactory RMSD of 2.380 Å.

As the neurotoxins 1BEI, 1BGK, 1ROO, and 2K9E were structurally similar, they were grouped into two clusters based on pairwise main-chain RMSD (Fig. 4). Structures in the first cluster represented two-thirds of the sample with an RMSD of 1.88 Å. The second group had an RMSD of 2.93 Å from the first cluster center. A structural comparison between structures of the clusters is shown in Figure 4. Although it is difficult to distinguish clusters because of experimental restraints, we observed that the lowest energy structures, as evaluated by the MOE scoring function, all of them belonged to cluster 1. 1BEI and 1ROO were neurotoxins within the cluster 1, in which a major similarity was observed between them. This is somehow possible because 1BEI is derived from 1ROO, where 1BEI had a replacement of Lys22 for DAP22,32 and RMSD analysis showed that the replacement did not alter both the form and function of the neurotoxins.

The structural alignment of the docked neurotoxins with the Kv1.3 channel assessed here is the first study to assess the interaction of neurotoxins with channel pore. The unexpected result showed a similar geometry, as shown in Figure 5, as this parameter is thought to be involved in the recognition of neurotoxins by the channel.51 Our results suggested that neurotoxins occupy the channel pore with their aliphatic chains, thus blocking K ion flux through the channel (Fig. 5). The physical—chemical properties and the motive among the positions 21–27 are both important for the establishment of the complex (NT/Kv1.3) and, as a consequence, the generation of a biological response. The neurotoxins as other biological molecules contain patterns that have been preserved through evolution because they are important to the structure or function of the molecule. In the protein primary sequence where they consist of single conserved amino acid residues separated by long, variable regions, these conserved residues may come together to form a functional group when the protein is folded into its three-dimensional (3D) structure.52 On the other hand, patterns of conserved sequences can often highlight elements that are responsible for structural similarity between proteins and can be used to predict the 3D structure of a protein.

Figure 5.

Representation of the structural alignment of the neurotoxins docked with the Kv1.3 channel performed with MOE 2009.10. (A) Representation of the aligned neurotoxins at the interaction with the Kv1.3 channel. The long aliphatic chain from the residues of the neurotoxins inserts into the ion selectivity filter of the channel with the residues Arg11, Lys22, Tyr23, and Lys25. (B) Structural alignment performed with MOE 2009.10 beginning from the current 3D position of 1BEI (green), 2K9E (violet), 1ROO (blue), and 1BGK (yellow). The similar geometry of the neurotoxins suggests a fundamental characteristic to block the ion flux through the channel.

Based on our findings, we considered that the pattern or key motive, which is essential for the interaction with the Kv1.3 channel, represented by the regular expression: X(5)–[FT]–[KI]–X(3)–R–X(4)–Q–X(4)–M–K–Y–Q–K–[SY]–F,44,47 where X signifies any amino acid, and X(4) is equivalent to X–X–X–X. The square brackets indicate an alternative; thus, [SY] give an indication of the probability of S or Y occurring in this position. It is important to note that a sequence of elements of the pattern notation matches a sequence of amino acids only if the latter sequence can be partitioned into subsequences in such a way that each pattern element matches the corresponding subsequence in turn.

Pattern discovery has become an important area of Bioinformatics. The techniques for pattern discovery use exhaustive search and can be used to detect possible sites of interest and assign putative structure or function to proteins. Thus, they can be used to guide biological experiments, decreasing the time and money spent in discovering new biological knowledge.24

Conclusions

Discovering sequence motifs or repeated patterns is of greater biological importance because its identification can lead to determination of function and to elucidation of evolutionary relationships among sequences. Research on protein sequences revealed that specific sequence motifs in biological sequences exhibit important characteristics acting as catalytic sites or regions involved in binding a molecule. Identification of sequence motifs using experimental methods is not possible, because many times sequences do not share a global sequence similarity. In addition, there is an exponential rise in the volume of sequences in databases. In this paper, we focus on motifs in neurotoxins of B. granulifera and S. helianthus, which are topologically similar but have diverse primary sequences. We presented the common patterns in sequences that may block ion flux through the Kv1.3 channel. The structural similarity between the neurotoxins is a property that enables effective blockade of the channel, so our findings validated the significance of the histidine ring as a residue implicated in the interactions of the channel with neurotoxins 1ROO, BGK, 2 K9E, and 1BEI. The novelty presented here relies on the pattern of interaction expressed as X(5)–[FT]–[KI]–X(3)–R–X(4)–Q–X(4)–M–K–Y–Q–K–[SY]–F that may serve as an input to generate a stable bonding between the Kv1.3 channel and neurotoxins. The findings presented in this paper could serve as evidence of structural and functional conservation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Brian J. Smith from La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science for providing us the Kv1.3 channel model.

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Thomas Dandekar, Associate Editor

FUNDING: This work was supported in part by grant PUJ 004837.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JG. Analyzed the data: AS, JGM, DR. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: AS, VB. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: LM, GB, DR. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: GB, LM. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: JG. Made critical revisions and approved final version: GB. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beeton C, et al. Kv1.3 channels are therapeutics target for T cells-mediated autoimmune diseases. 2006;103(46):17414–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeton C, Chandy K. Potassium channels, memory T cells, and multiple sclerosis. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:550–62. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeton C, Wulff H, Singh S, et al. A novel fluorescent toxin to detect and investigate Kv1.3 channel up-regulation on chronical activated T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9928–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pozo-Rosich P, Clover L, Saiz A, Vincent A, Graus F. Voltage-gated potassium channel antibodies in limbic encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:530–3. doi: 10.1002/ana.10713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeton C, Barbaria J, Giraud P, et al. Selective blocking of voltage-gated K+ channels improves experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and inhibits T cell activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:936–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norton RS, Pennington MW, Wulff H. Potassium channel blockade by the sea anemone toxin ShK for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;11:3141–52. doi: 10.2174/0929867043363947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson A, Diamons B. Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:340–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi V, Pennington MW, Norton RS, et al. Development of a sea anemone toxin as an immunomodulator for therapy of autoimmune diseases. Toxicon. 2012;4:529–46. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beeton C, Pennington MW, Norton RS. Analogs of the sea anemone potassium channel blocker ShK for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10(5):313–21. doi: 10.2174/187152811797200641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalman K, Pennington MW, Lanigan MD, et al. ShK-Dap22, a potent Kv1.3-specific immunosuppressive polypeptide. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32697–707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dichot S, Lazdunski M. Sea anemone toxins affecting potassium channels. Marine toxins as research tools. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2009;46:99–122. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-87895-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catterall WA, Cestèle S, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Yu FH, Konoki K, Scheuer T. Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon. 2007;49:124–41. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judge SIV, Bever CT. Potassium channel blockers in multiple sclerosis: neuronal Kv channels and effects of symptomatic treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:224–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha J, et al. Cnidarians as a source of new marine bioactive compounds— an overview of the last decade and future steps for bioprospecting. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1860–89. doi: 10.3390/md9101860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton RS. Structures of anemone toxin. Toxicon. 2009;34(2):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kem WR. Sea anemone toxins: structure and action. In: Hessinger DA, Lenhoff HM, editors. The Biology of Nematocysts. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; Toxicon; 1988. pp. 76–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kita M, Kitamura M, Uemura D. Mori K, editor. Comprehensive Natural Products. 4 Chap 6. 2nd ed. ed. Mori. Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tudor JE, Pallaghy PK, Pennington MW, Norton S. Solution structure of Shk toxin, a novel potassium channel inhibitor from a sea anemone. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:317–20. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wulff H, Castle N, Pardo L. Voltage-gate potassium channels as therapeutic drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;2(12):982–1001. doi: 10.1038/nrd2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wulff H, Zhorov B. K+ channel modulators for the treatment of neurological disorders and autoimmune diseases. Chem Rev. 2008;108(5):1744–73. doi: 10.1021/cr078234p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baell JB, Gable RW, Harvey AJ, et al. Khellinone derivatives as blockers of the voltaged potassium channel Kv1.3: synthesis and immunosuppressive activity. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2326–36. doi: 10.1021/jm030523s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle D, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, et al. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rauer H, et al. Structural conservation of the pores of calcium-activated and voltage-gated. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(31):21885–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beeton C, Smith BJ, Sabo JK, et al. The d-diastereomer of ShK toxin selectively blocks voltage-gated K+ channels and inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(2):988–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu L, Gocke AR, Knapp E, et al. Functional blockade of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 mediates reversion of T effector to central memory lymphocytes through SMAD3/p21cip1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(2):1261–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.296798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li HL, Sui HX, Ghanshani S, et al. Two dimensional crystallization and projection structure of KscA potassium channel. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:211–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashid MH, Mahdavi S, Kuyucak S. Computational studies of marine toxins targeting ion channels. Mar Drugs. 2013;11(3):848–69. doi: 10.3390/md11030848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, Xu D, Liang D. Computational Methods for Protein Structure Prediction and Modeling. Springer; Georgia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morales L, Acevedo O, Martínez M, Gokhman D, Corredor C. Functional discrimination of sea anemone neurotoxins using 3D-plotting. Cent Eur J Biol. 2009;4(1):41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rashid H, Kuyucak S. Affinity and selectivity of ShK toxin for the Kv1 potassium channels from free energy simulations. J Phys Chem. 2012;116(16):4812–22. doi: 10.1021/jp300639x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jana S, Metcalfe G, Ottino J. Experimental and computational studies of mixing in complex stokes flows: the vortex mixing flow and multicellular cavity flows. J Fluid Mech. 1994;269:199–246. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennington MW, Beeton C, Galea CA, et al. Engineering a stable and selective peptide blocker of the Kv1.3 channel in T lymphocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:762–73. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dauplais M, Lecoq A, Song J, et al. On the convergent evolution of animal toxins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(7):4302–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cotton J, Crest M, Bouet F, et al. A potassium-channel toxin from the sea anemone Bunodosoma granulifera. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alessandri-Haber N, Lecoq A, Gasparini S, et al. Mapping the functional anatomy of BgK on Kv1.1, Kv1.2 and Kv1.3. clues to design analogs with enhanced selectivity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(50):35653–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilquin B, Racapé J, Wrisch A, et al. Structure of the BgK-Kv1.1 complex based on distance restraints identified by double mutant cycles. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):37406–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han S, Yi H, Yin SJ, et al. Structural basis of a potent peptide inhibitor designed for Kv1.3 channel, a therapeutic target of autoimmune disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(27):19058–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiser A, Sali A. Comparative structure modelling with MODELLER: a practical approach. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:463–93. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarcha EJ, Chi V, Muñoz-Elías EJ, et al. Durable pharmacological responses from the peptide ShK-186, a specific Kv1.3 channel inhibitor that suppresses T cell mediators of autoimmune disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342(3):642–53. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.191890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchie D, Kemp G. Protein docking using spherical polar Fourier correlations. Proteins. 2000;39:178–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozakov D, Hall DR, Beglov D, et al. Achieving reliability and high accuracy in automated protein docking. ClusPro, PIPER, SDU, and stability analysis in CAPRI rounds 13–19. Proteins. 2010;78:3124–30. doi: 10.1002/prot.22835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kozakov D, Brenke R, Comeau SR, Vajda S. Piper: an FTT-based protein docking program with pairwise potentials. Proteins. 2006;65:392–406. doi: 10.1002/prot.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Comeau S, Gatchell DW, Vajda S, Camacho CJ. ClusPro: a fully automated algorithm for protein-protein docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;34:96–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace A, Laskowski R, Thornton J. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995;8:127–34. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeLano WW. PyMOL: An Open-Source Molecular Graphics Tool. Schrödinger, LLC; (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vilar S, Cozza G, Moro S. Medicinal chemistry and the molecular operating environment (MOE): applications of QSAR and molecular docking to drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8(18):1555–72. doi: 10.2174/156802608786786624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiong J. Essential Bioinformatics. Cambridge University Press; Texas: 2009. pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mullen KM, Rozycka M, Rus H, et al. Potassium channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 are expressed on blood-derived dendritic cells in the central nervous system. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:118–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Consortium TU. Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D71–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lanigan MD, Kalman K, Lefievre Y, Pennington MW, Chandy KG, Norton RS. Mutating a critical lysine in ShK toxin alters its binding configuration in the pore-vestibule region of the voltage-gated potassium channel, Kv1.3. Biochemistry. 2002;41(40):11963–71. doi: 10.1021/bi026400b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen R, Robinson A, Gordon D, Chung SH. Modeling the binding of three toxins to the voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv1.3) Biophys J. 2011;101(11):2652–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brejova C, Romero S, Holguin G. (Project report for CS798 g).Finding Patterns in Biological Sequences. 2000 Fall; [Google Scholar]