Abstract

Weight concerns are common among female smokers and may interfere with smoking cessation. It is imperative to identify protective factors to lessen the likelihood that smoking-related weight concerns prompt smoking and hinder cessation efforts. Mindfulness is one potential protective factor that might prevent weight concerns from triggering smoking. In the current study, relationships among facets of trait mindfulness, smoking-related weight concerns, and smoking behavior were examined among 112 young adult female smokers (70.5% daily smokers; 83% Caucasian; mean age 20 [SD = 1.69]). After controlling for demographic variables, the Describing facet of trait mindfulness predicted lower smoking-related weight concerns. The mindfulness characteristics of Acting with Awareness, Nonreactivity, and Describing moderated the relationship between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking frequency, such that smoking-related weight concerns predicted greater smoking frequency in female smokers with low and medium levels of these mindfulness characteristics but did not in those with higher levels of mindfulness. These results suggest that mindfulness-based interventions may be effective for weight-concerned smokers.

Keywords: Trait Mindfulness, Facets of Mindfulness, Smoking, Weight Concerns

Introduction

Weight concerns are common among cigarette smokers, particularly for females (Bush et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2006; Pomerleau, Zucker, & Stewart, 2001). Smoking-specific weight concerns (i.e., the tendency to use smoking as a way to control appetite and weight; concern about gaining weight upon smoking cessation) often predict higher smoking frequency, higher nicotine dependence, lower desire to quit smoking, and worse smoking cessation outcomes (Adams, Baillie, & Copeland, 2011; Clark et al., 2006; Copeland & Carney, 2003; Copeland, Martin, Geiselman, Rash, & Kendzor, 2006; Jeffery, Hennrikus, Lando, Murray, & Liu, 2000; Pomerleau et al., 2001; Weekley, Klesges, & Reylea, 1992). Thus, it is imperative for research to identify protective factors that might ameliorate the relationship between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking behavior, thereby improving smoking cessation among weight-concerned women.

One potential protective factor is mindfulness (a mode of meta-cognitive awareness in which individuals observe their present-moment experiences with an attitude of acceptance; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006; Kabat-Zinn, 1990, 1994). Mindfulness involves an open, nonjudgmental attitude toward experience and is thought to lessen the tendency to try to avoid unpleasant thoughts or emotions (Bishop et al., 2004). Research suggests that mindfulness not only reduces negative affect (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003; Chambers, Lo, & Allen, 2008; Erisman & Roemer, 2012; Jain et al., 2007; McKee, Zvolensky, Solomon, Bernstein, & Leen-Feldner, 2007) but also changes the way individuals respond to distress, helping them observe and accept unpleasant experiences without trying to escape them (Arch & Craske, 2006; 2010; Bieling et al., 2012). In other words, mindfulness may moderate (or weaken) associations between distress and behavioral responses, reducing the likelihood that unpleasant experiences trigger impulsive, maladaptive patterns of reactivity.

Mounting evidence supports mindfulness as a moderator of associations between psychosocial risk factors and negative behavioral outcomes. For example, Ostafin and Marlatt (2008) found that mindfulness (particularly the tendency to accept experiences nonjudgmentally) weakened the association between automatic alcohol motivation and hazardous drinking. These results suggest that mindfulness weakens the tendency for automatic mental impulses to carry over into maladaptive behavior. In a similar vein, Barnhofer, Duggan, and Griffith (2011) reported that mindfulness moderated the association between neuroticism (typically a strong risk factor for depression) and current depressive symptoms. Furthermore, Masuda, Price, and Latzman (2012) found that mindfulness attenuated the association between dysfunctional eating-related thoughts (e.g., fear of weight gain) and disordered eating.

Adams, Benitez and colleagues (2012) recently found support for mindfulness as a moderator between distress and smoking. Specifically, brief mindfulness instructions weakened the association between negative affect and urges to smoke. Bowen and Marlatt (2009) reported similar evidence that mindfulness attenuated the relationship between negative affect and smoking urges. These results suggest that mindfulness may prevent affective distress from influencing smoking urges. Similarly, mindfulness might moderate the relationship between weight concerns and smoking, such that among more mindful smokers, concerns about eating and body weight are less likely to trigger smoking urges and behavior. That is, a smoker with greater levels of trait mindfulness may be more likely to observe and accept her concerns about eating and weight without smoking to escape these unpleasant thoughts.

Although mindfulness-based treatments have not yet been applied specifically for weight-concerned smokers, there is evidence that mindfulness-based interventions can improve body image and smoking cessation (Brewer et al., 2011; Davis, Fleming, Bonus, & Baker, 2007; Delinsky & Wilson, 2006). Furthermore, trait mindfulness has been associated with lower levels of bulimic symptoms and disordered eating-related cognitions in college populations (Adams, McVay et al., 2012; Lavender et al., 2009; Masuda & Wendell, 2010).

Although most mindfulness studies have examined mindfulness as a unitary construct, research suggests that mindfulness is multidimensional (Baer et al., 2006; Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010). Baer and colleagues (2006) conducted a factor analysis of items on five psychometrically-sound mindfulness questionnaires and found five main facets of mindfulness: 1) Nonreactivity (perceiving thoughts and feelings without reacting to them), 2) Observing (paying attention to internal and external sensations), 3) Acting with Awareness (staying focused on present-moment experience and acting deliberately; opposite of being on “automatic pilot”), 4) Describing (describing/labeling thoughts and feelings with words), and 5) Nonjudging (accepting thoughts and emotions without labeling them as “good” or “bad”). Baer et al. (2006) reported that these factors differentially predicted personality measures and psychological symptoms. For example, the Nonreactivity factor was most strongly correlated with self-compassion, and the Describing score was related to higher emotional intelligence. Whereas most subscales predicted lower psychopathology, the Observing subscale was related to higher psychological symptoms. In examining these facets in relation to eating pathology, Lavender, Gratz, and Tull (2011) found that Nonreactivity, Acting with Awareness, and Nonjudging, but not Observing, were associated with lower eating disorder symptoms. In Lavender et al.’s (2011) study, the Describing facet was unexpectedly related to higher eating disorder symptoms. There is a need for further research to elucidate unique effects of various facets of mindfulness.

In sum, mindfulness may be beneficial for improving attitudes about body weight and shape (Adams, McVay et al., 2012; Delinsky & Wilson, 2006; Lavender et al. 2009; Masuda & Wendell, 2010) and promoting smoking cessation (Brewer et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2007). Furthermore, mindfulness is best viewed as a multidimensional construct (Baer et al., 2006; Lavender et al., 2011). It is possible that particular aspects of mindfulness weaken the extent to which smoking-related weight concerns trigger smoking behavior. Perhaps more mindful smokers have greater confidence in their abilities (i.e., self-efficacy) to regulate their behavior in the midst of unpleasant thoughts like weight concerns. Indeed, extant research suggests that more mindful individuals perceive greater ability to regulate their emotions without smoking (Vidrine et al., 2009). Higher trait mindfulness is also associated with greater self-efficacy for changing other health-related behaviors like diet and physical activity (Gilbert & Waltz, 2010).

The present study examined the role of mindfulness as a moderator of the relationship between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking frequency among female smokers. It was hypothesized that smoking-related weight concerns would predict higher smoking frequency and nicotine dependence among smokers low in trait mindfulness but not among those with high levels of trait mindfulness. It was also hypothesized that whereas most of the facets of mindfulness would ameliorate the relationship between weight concerns and smoking, the Observing facet would not emerge as a significant moderator.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 112) were undergraduate women (ages 18–26) who self-identified as smokers. Given that college students tend to be light smokers (Sutfin, Reboussin, McCoy, & Wolfson, 2009), participants were not required to smoke a certain number of cigarettes per day. As this sample included non-daily smokers, smoking frequency in the overall sample was defined as number of cigarettes smoked per week.

Materials

The Five-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006) is a 39-item self-report assessment of trait mindfulness yielding five factors: 1) Nonreactivity (e.g., “I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them”), 2) Observing (e.g., “I pay attention to sensations, such as the wind in my hair or sun on my face”), 3) Acting with Awareness (e.g., “It seems I am ‘running on automatic’ without much awareness of what I’m doing” [reverse-coded]), 4) Describing (e.g., I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings”), and 5) Nonjudging (e.g., “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way I’m feeling” [reverse-coded]). Participants rate each item from 1 (“never or rarely true”) to 5 (“very often or always true”). The FFMQ and its subscales have shown good reliability and validity (Baer et al., 2006).

The Smoking-related Weight and Eating Episodes Test (SWEET; Adams et al., 2011) is a 10-item self-report measure of smoking-specific weight concerns. The scale yields a total score as well as four subscale scores: 1) smoking to suppress appetite (Appetite; e.g., “When I feel hungry, I have a cigarette to curb my appetite”), 2) smoking to prevent overeating (Overeating; e.g., “Smoking after a meal helps me to avoid overeating”), 3) smoking to cope with body dissatisfaction (Body Dissatisfaction; e.g., “When I feel fat, I have a cigarette”), and 4) withdrawal-related appetite increases (Withdrawal; e.g., “I crave tasty foods when I haven’t smoked in a while”). Participants rate how often each statement describes them, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always.” Scores are averaged so that the total score ranges from 1 to 5. Preliminary validation of the SWEET indicated excellent internal consistency. Female smokers with higher scores on the SWEET tend to view smoking as a way to control weight, indicate elevated body dissatisfaction, and report greater concern about gaining weight upon smoking cessation (Adams et al., 2011).

The Smoking Status Questionnaire (SSQ) is a self-report assessment of demographic characteristics and smoking behavior. Daily smokers were asked to report the number of cigarettes they smoked per day and complete the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), a widely-used 6-item measure of nicotine dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). The FTND has been consistently related to higher smoking frequency, biochemical smoking assessments, and nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Heatherton et al., 1991; Ríos-Bedoya, Snedecor, Pomerleau, & Pomerleau, 2008). Total scores can range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicting higher nicotine dependence. Non-daily smokers reported the number of cigarettes they smoked per week.

Procedure

Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the large southeastern university where these data were collected as part of a larger study examining associations between mindfulness, smoking, and body image (Adams, Benitez et al., 2012). Participants were recruited through campus fliers and the undergraduate psychology participant pool. Participants chose to be compensated either with course credit or $10. When participants arrived, expired carbon monoxide (CO; Vitalograph Incorporated, Lenexa, KS, USA) levels were assessed with a portable Vitalograph ecolyzer. Participants then completed the FFMQ, SSQ, and SWEET. Height and weight were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight, in kilograms, divided by height, in meters squared (kg/m2).

Statistical Analyses

Prior to primary analyses, a series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to test direct relationships between mindfulness and the six dependent variables of interest (smoking frequency, nicotine dependence, and facets of smoking-related weight concerns). As age, race/ethnicity, and BMI are additional factors related to smoking patterns and weight concerns among female smokers (Adams et al., 2011), these were entered as covariates on Step 1. The five FFMQ factors (Observing, Describing, Acting with Awareness, Nonreactivity, and Nonjudging) were entered on Step 2 in order to assess the unique contribution of each of these facets in predicting dependent variables.

To test whether mindfulness moderated the relationship between smoking-related weight concern and smoking behavior, age, race/ethnicity, and BMI were entered on Step 1; the FFMQ subscale score to be tested and smoking-related weight concern (SWEET total score [rather than SWEET subscale scores in order to reduce Type I error]) were entered on Step 2, and the zero-centered interaction term between FFMQ subscale scores and the SWEET total score was entered on Step 3 (interactions involving each FFMQ subscale score were tested in separate models). Dependent variables were smoking frequency and nicotine dependence. Significant interactions were probed using tests of simple effects (Aiken & West, 1991) within tertiles of mindfulness scores in order to ascertain the association between weight concerns and smoking among participants with higher versus lower trait mindfulness. In regression analyses, outliers greater than 3.3 standard deviations from their predicted mean were removed (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The majority of participants (83%) were Caucasian, and the mean age was 20 (SD = 1.69). Average BMI was in the normal range (M = 24.00, SD = 4.91). Seventy-nine participants (70.5%) reported smoking every day (M = 8.53 cigarettes per day, SD = 5.02) and tended to have low nicotine dependence (FTND M = 1.84, SD = 1.69). Daily smokers reported having smoked for an average of 2.73 (SD = 1.82) years. Among non-daily smokers, 16 (48%) indicated having smoked daily in the past for an average of 3.13 (SD = 1.59) years. The total sample reported currently smoking 45.23 (SD = 38.05) cigarettes per week. CO levels were relatively low (M = 5.80, SD = 5.32), consistent with the finding that many college students are light smokers (Sutfin et al., 2009). The mean SWEET total score was 2.30 (SD = .80), indicating low to moderate tendency to use smoking for weight control.

Preliminary Analyses: Mindfulness, Smoking, and Smoking-related Weight Concerns

After controlling for age, BMI, and race/ethnicity, mindfulness did not predict smoking frequency (p = .43) or nicotine dependence (p = .46) in Step 2 of the regression analysis. However, Step 2 of the regression analysis was significant in predicting all SWEET subscales above and beyond demographics (Appetite: F[5, 99] = 2.81, p = .02; Overeating: F[5, 99] = 2.86, p = .02; Body Dissatisfaction: F[5, 99] = 5.66, p < .001; Withdrawal: F[5, 99] = 2.75, p = .02). As this overall step of the regression was significant, individual coefficients were examined to determine the direction of the association between each FFMQ subscale and SWEET scores. Specifically, among the FFMQ subscales, Observing and Describing each uniquely predicted SWEET scores but in different ways. Observing predicted higher SWEET scores on three of the subscales (Appetite: t[99] =2.48, p = .02, sr2 = .05; Body Dissatisfaction: t[99] = 3.20, p = .002, sr2 = .07; Withdrawal: t[99] = 2.83, p = .01, sr2 = .07). Describing predicted lower scores on two SWEET subscales (Overeating: t[99] = −3.31, p = .001, sr2 = .09; Body Dissatisfaction: t[99] = −3.56, p = .001, sr2 = .09).

Primary Analyses: Moderating Effects of Mindfulness

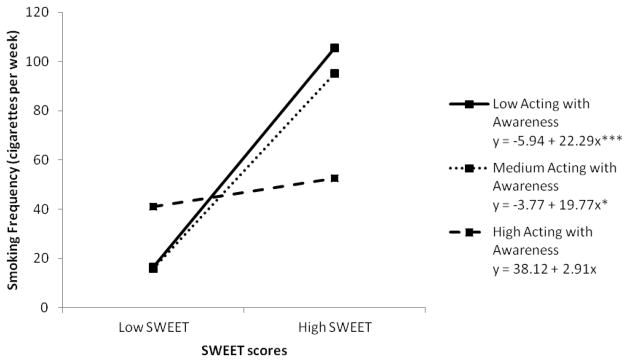

The FFMQ Acting with Awareness factor moderated the relationship between SWEET total scores and smoking frequency, t(102) = 1.99, p = .049, sr2 = .04. Follow-up tests of simple effects were conducted within tertiles of Acting with Awareness (Low: ≤ 21, Medium: 22–26, High: ≥ 27). These tests indicated that after controlling for covariates, smoking-related weight concerns predicted higher smoking frequency among participants with low and medium scores on Acting with Awareness, (Low: t[33] = 4.17, p < .001, sr2 = .31; Medium: t[28] = 2.31, p = .03, sr2 = .15). However, smoking-related weight concerns were unrelated to smoking frequency among participants with high Acting with Awareness scores, p = .52 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction between Five-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) Acting with Awareness and smoking-related weight concerns (Smoking-related Weight and Eating Episodes Test [SWEET]) in predicting smoking frequency. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

The FFMQ Nonreactivity factor also moderated the relationship between SWEET scores and smoking frequency, t(101) = 2.75, p = .01, sr2 = .07. Follow-up tests of simple effects were conducted within tertiles of Nonreactivity (Low: ≤ 18, Medium: 19–21, High: ≥ 22). These tests indicated that after controlling for covariates, smoking-related weight concerns predicted higher smoking frequency among participants with low and medium scores on Nonreactivity (Low: t[30] = 3.63, p = .001, sr2 = .30; Medium: t[34] = 2.50, p = .02, sr2 = .14) but not among those with high Nonreactivity scores, p = .86 (Virtually identical to pattern in Figure 1).

The FFMQ Describing factor moderated the relationship between SWEET scores and smoking frequency, t(102) = 2.16, p = .03, sr2 = .04. Follow-up tests of simple effects were conducted within tertiles of Describing (Low: ≤ 24, Medium: 25–30, High: ≥ 31). After controlling for covariates, smoking-related weight concerns predicted higher smoking frequency among participants with low and medium Describing scores, (Low: t[28] = 2.31, p = .03, sr2 = .15; Medium: t[33] = 2.70, p = .01, sr2 = .15) but not among those with high Describing scores, p = .55 (Also similar to Figure 1).

Discussion

The current study tested the hypothesis that greater trait mindfulness ameliorates the relationship between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking behavior. As hypothesized, mindfulness moderated the association between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking frequency. Smoking-related weight concerns predicted higher smoking frequency among smokers lower but not higher in trait mindfulness. In particular, this study highlights Describing, Acting with Awareness, and Nonreactivity as aspects of mindfulness that ameliorate the relationship between smoking-specific weight concerns and smoking frequency. These findings suggest that women who are able to describe and label their feelings with words, concentrate on present-moment experience, and perceive thoughts and feelings without reacting to them may be better equipped to cope with weight concerns. It is possible that these mindfulness characteristics might result in lower smoking frequency and less difficulty with cessation.

More information is needed regarding the mechanisms by which mindfulness weakens the link between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking behavior. One potential mechanism is that mindfulness skills promote self-efficacy to regulate eating and weight without smoking. Perhaps more mindful individuals are more confident in their abilities to cope with food cravings, body image stimuli, and associated distress without turning to cigarettes. Indeed, research suggests that among individuals attempting to quit smoking, those higher in trait mindfulness report higher confidence in their ability to cope with high-risk situations without smoking than those lower in trait mindfulness (Vidrine et al., 2009). Mindfulness-based smoking cessation interventions that emphasize Describing, Acting with Awareness, and Nonreactivity skills might benefit female smokers who use smoking to control weight, so these weight concerns are less likely to interfere with cessation.

In the present study, female smokers with higher trait mindfulness were less likely to smoke as a way of controlling eating or coping with body image concerns. Describing (the tendency to describe or label experiences in words) was a particularly beneficial aspect of mindfulness in this respect. These results are somewhat inconsistent with those of Lavender et al. (2011), which indicated that Describing was related to greater eating pathology among non-smoking college women. Given that there are few studies examining unique effects of mindfulness facets, more research is needed to clarify which aspects are uniquely associated with eating habits and weight concerns among smokers and non-smokers.

As expected, Observing (noticing and paying attention to internal and external sensations) did not uniquely benefit smoking-related weight concerns. In fact, Observing was related to higher likelihood of smoking to control appetite, increased tendency to smoke in response to body image concerns, and higher likelihood of withdrawal-associated appetite increases. This is consistent with findings purporting that although most aspects of mindfulness predict better psychological outcomes, Observing is actually related to higher psychological symptoms (Baer et al. 2006). This suggests that simply observing present-moment experience (a key component of mindfulness) is not necessarily beneficial to psychological health unless it is combined with other aspects of mindfulness (i.e., Describing, Acting with Awareness, Nonreactivity, and Nonjudging).

Although mindfulness was related to lower smoking-related weight concerns, it did not directly predict smoking frequency or nicotine dependence. This finding is inconsistent with those of Vidrine et al. (2009), who reported that smokers higher in trait mindfulness had lower levels of nicotine dependence. This discrepancy is likely due to differences between the present sample and that in Vidrine et al.’s (2009) study. While the present sample included female undergraduates who were primarily Caucasian and light smokers, Vidrine and colleagues’ (2009) community sample was more ethnically diverse, included males, consisted of heavier smokers, and included participants with lower education levels than those in the current sample.

The present study had several limitations. First and foremost, this study was cross-sectional and does not imply causality. Longitudinal studies will be necessary to suggest the temporal nature of relationships among mindfulness, weight concerns, and smoking characteristics. This study included a relatively small and homogenous sample made up of primarily Caucasian female undergraduates who tended to be light smokers and were not necessarily interested in quitting smoking. Future research should examine potential moderating effects of mindfulness on relationships between smoking-specific weight concerns and rates of smoking abstinence among individuals attempting to quit smoking, as well as heavier smokers.

The current study is strengthened by its investigation of multiple dimensions of mindfulness. This study examined not only direct but also moderating effects of mindfulness, offering insight into specific ways in which mindfulness changes the relationship between weight concerns and smoking behavior. Furthermore, self-report measures were supplemented by biochemical verification of smoking and objective measures of height and weight. Future researchers are encouraged to conduct large randomized controlled trials on the effects of mindfulness-based treatment for smoking cessation, weight concerns, and the extent to which weight concerns predict smoking cessation. Research on mechanisms of mindfulness among weight-concerned female smokers would be helpful for tailoring treatment for this population.

The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that female smokers with higher trait mindfulness report lower smoking-specific weight concerns. Furthermore, mindfulness appears to weaken the link between smoking-related weight concerns and smoking behavior. Although research suggests that women who smoke to control appetite and weight tend to be heavier smokers with higher nicotine dependence, lower desire to quit, and worse cessation outcomes (Adams et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2006; Copeland et al., 2006; Copeland & Carney, 2003; Jeffery et al., 2000; Pomerleau et al., 2001; Weekley et al., 1992), the current study suggests that this might not be the case for smokers high in trait mindfulness. Mindfulness-based treatments are one promising avenue for reducing weight concerns and improving coping with weight concerns that might otherwise prompt increased smoking and difficulties quitting. Treatments targeting the specific mindfulness skills of describing experiences with words, acting with awareness, and perceiving thoughts and feelings without reacting to them might be especially effective for aiding female smokers in coping with weight concerns.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted at Louisiana State University and supported in part by a grant to Dr. Adams from the American Psychological Association. Dr. Adams and Dr. Stewart are currently at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and have received support from the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672) and a cancer prevention fellowship (R25T CA57730: PI Shine Chang). Dr. Adams is currently supported by a faculty fellowship from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment. The authors would like to thank Allyson Barbry and Alexa Thibodeaux for their work in data collection for this study.

Contributor Information

Claire E. Adams, Email: cadams@mdanderson.org, Department of Health Disparities Research, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center – Unit 1440, PO Box 301402, Houston, TX 77230-1402.

Megan Apperson McVay, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center.

Diana W. Stewart, Department of Health Disparities Research, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center – Unit 1440, PO Box 301402, Houston, TX 77230-1402

Christine Vinci, Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA.

Jessica Kinsaul, Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA.

Lindsay Benitez, Department of Psychology, The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Chattanooga, TN.

Amy L. Copeland, Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA

References

- Adams CE, Baillie LE, Copeland AL. The smoking-related weight and eating episodes test (SWEET): Development and preliminary validation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13:1123–1131. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CE, McVay MA, Kinsaul J, Benitez L, Vinci C, Stewart DW, Copeland AL. Unique relationships between facets of mindfulness and eating pathology among female smokers. Eating Behaviors. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.05.009. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CE, Benitez L, Kinsaul J, McVay MA, Barbry A, Thibodeaux A, Copeland AL. Effects of brief mindfulness instructions on reactions to body image stimuli among female smokers: An experimental study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts133. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Laboratory stressors in clinically anxious and non-anxious : The moderating role of mindfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: Emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1849–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhofer T, Duggan DS, Griffith JW. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relation between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51:958–962. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Hawley LL, Bloch RT, Corcoran KM, Levitan RD, Young LT, MacQueen GM, Segal ZV. Treatment-specific changes in decentering following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus antidepressant medication or placebo for prevention of depressive relapse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027483. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, Devins G. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Marlatt A. Surfing the urge: Brief mindfulness-based intervention for college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:666–671. doi: 10.1037/a0017127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Mallik S, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Johnson HE, Deleone CM, Rounsaville BJ. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;119:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush T, Levine MD, Deprey M, Cerutti B, Zbikowski SM, McAfee T, Beebe L. Prevalence of weight concerns and obesity among smokers calling a quitline. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2009;4:74–78. doi: 10.1375/jsc.4.2.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Lo BCY, Allen NB. The impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, Hurt RD, Croghan IT, Patten CA, Novotny P, Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL. The prevalence of weight concerns in a smoking abstinence clinical trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KA, Hartman M, Fredrickson BL. Deconstructing mindfulness and constructing mental health: Understanding mindfulness and its mechanisms of action. Mindfulness. 2010;1:235–253. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0033-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Carney CE. Smoking expectancies as mediators between dietary restraint and disinhibition and smoking in college women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:247–251. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Martin PD, Geiselman PJ, Rash CJ, Kendzor DE. Predictors of pretreatment attrition from smoking cessation among pre- and postmenopausal, weight-concerned women. Eating Behaviors. 2006;7:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Fleming MF, Bonus KA, Baker TB. A pilot study on mindfulness based stress reduction for smokers. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;7:2–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delinsky SS, Wilson GT. Mirror exposure for the treatment of body image disturbance. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:108–116. doi: 10.1002/eat.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisman SM, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the process of mindfulness. Mindfulness. 2012;3:30–43. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0078-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D, Waltz J. Mindfulness and health behaviors. Mindfulness. 2010;1:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0032-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, Schwartz GE. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditations versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, Murray DM, Liu JW. Reconciling conflicting findings regarding postcessation weight concerns and success in smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2000;19:242–246. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacourt; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness and meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Gratz KL, Tull MT. Exploring the relationship between facets of mindfulness and eating pathology in women. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2011;40:174–182. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.555485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Jardin BF, Anderson DA. Bulimic symptoms in undergraduate men and women: Contributions of mindfulness and thought suppression. Eating Behaviors. 2009;10:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, Price M, Latzman RD. Mindfulness moderates the relationship between disordered eating cognitions and disordered eating behaviors in a non-clinical college sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s10862-011-9252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, Wendell JW. Mindfulness mediates the relation between disordered eating-related cognitions and psychological distress. Eating Behaviors. 2010;11:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Zvolensky MJ, Solomon SE, Bernstein A, Leen-Feldner E. Emotional vulnerability and mindfulness: A preliminary test of associations among negative affectivity, anxiety sensitivity, and mindfulness skills. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:91–101. doi: 10.1080/16506070601119314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostafin BD, Marlatt G. Surfing the urge: Experiential acceptance moderates the relation between automatic alcohol motivation and hazardous drinking. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:404–418. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.4.404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Zucker AN, Stewart AJ. Characterizing concerns about post- cessation weight gain: Results from a national survey of women smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3:51–60. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Bedoya CF, Snedecor SM, Pomerleau CS, Pomerleau OF. Association of withdrawal features with nicotine dependence as measured by the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1086–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, Reboussin BA, McCoy TP, Wolfson M. Are college student smokers really a homogenous group? A latent class analysis of college student smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;1:444–454. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5. Boston: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Cincirpini P, Li Y, Marcus MT, Waters AJ, Wetter DW. Associations of mindfulness with nicotine dependence, withdrawal, and agency. Substance Abuse. 2009;30:318–327. doi: 10.1080/08897070903252973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekley CK, Klesges RC, Reylea G. Smoking as a weight-control strategy and its relationship to smoking status. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:259–271. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90031-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]