Abstract

The repressive compartment of the nucleus is comprised primarily of telomeric and centromeric regions, the silent portion of ribosomal RNA genes, the majority of transposable element repeats, and facultatively repressed genes specific to different cell types. This compartment localizes into three main regions: the peripheral heterochromatin, perinucleolar heterochromatin, and pericentromeric heterochromatin. Both chromatin remodeling proteins and transcription of noncoding RNAs are involved in maintenance of repression in these compartments. Global reorganization of the repressive compartment occurs at each cell division, during early development, and during terminal differentiation. Differential action of chromatin remodeling complexes and boundary element looping activities are involved in mediating these organizational changes. We discuss the evidence that heterochromatin formation and compartmentalization may drive nuclear organization.

Keywords: heterochromatin, chromatin organization, nuclear periphery, nucleolus, nuclear organization

Introduction

The nuclei of differentiated cells contain heterochromatic and euchromatic compartments. The heterochromatic compartment is primarily repressive, whereas the euchromatic compartment harbors more active gene expression. The spatial organization of chromatin within and between these compartments can differ significantly among cell types, and changes in this organization likely help drive development (Felsenfeld & Dekker 2012, Rajapakse & Groudine 2011, Sexton et al. 2007).

The presence of an organized repressive compartment is now considered a hallmark of the differentiated cell, as early embryo and some stem cells contain relatively little compartmentalized heterochromatin (Lessard & Crabtree 2010, Reik et al. 2001). Heitz (1928) originally defined heterochromatin microscopically as condensed chromosomal regions that stained intensely and did not disappear during mitosis. Its presence in chromocenters and association with nucleoli were also reported at this time (for historical review, see Jost et al. 2012). After nearly a century, it is possible to add to the definition: Heterochromatin is also DNAse I resistant and replicates during mid to late S phase. DNAse I treatment has been used for many years as a tool to identify expressed genes (Weintraub & Groudine 1976), because as a rule, the DNA of active genes is decondensed and more available for cleavage by DNAse I, whereas heterochromatin is more highly condensed and relatively resistant. Different classes of heterochromatic DNA initiate replication later in S phase than does euchromatin and can be correlated with specific replication timing profiles (Filion et al. 2010, O'Keefe et al. 1992, Wu et al. 2005). Telomeric and centromeric DNA; inactive ribosomal DNA (rDNA); developmentally repressed genes, including polycomb and Sir repressed genes; and other repetitive DNA, including transposable elements (TEs), fall within this category. Specific DNA-binding proteins and DNA and histone modifications (or the lack thereof) mark heterochromatin classes (Black et al. 2012).

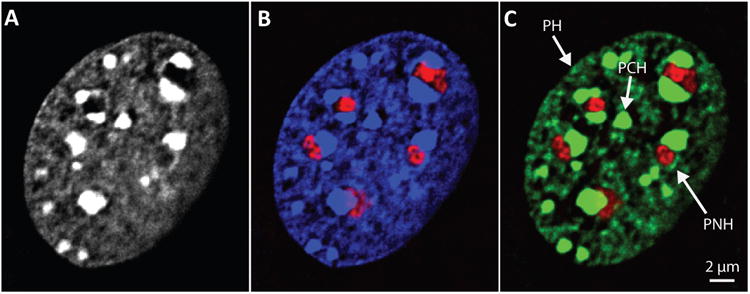

As Heitz described, the global organization of heterochromatic DNA in the nucleus can be observed to a first approximation by using simple stains. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) is commonly used in fixed cells and Hoescht 33342 in live cells. Alternately, antibodies to various histone-binding proteins or histone marks can be used to immunostain particular classes of heterochromatin. The DNA dyes have a high affinity for AT-rich heterochromatic regions and also concentrate in these highly condensed regions, resulting in a brighter stain when compared with euchromatic regions. Figure 1 shows a mouse embryonic fibroblast stained with DAPI; antibodies to the repressive histone mark, H3K9me3 (trimethylated lysine 9 on histone H3); and fibrillarin, a protein that concentrates in the nucleolus. A ring of heterochromatin is visible at the nuclear periphery and around the nucleolus, along with several brightly labeled spheres representing pericentromeric heterochromatin (PCH loci, or chromocenters). These three main repressive classes, peripheral heterochromatin (PH), perinucleolar heterochromatin (PNH), and PCH, make up the bulk of the repressive compartment. We discuss how heterochromatin is distributed among the three classes and examine how chromatin movements to and from the repressive compartment might drive changes in nuclear organization during development. We also posit that heterochromatin formation and compartmentalization itself might seed global nuclear organization.

Figure 1.

Heterochromatin distribution in a mammalian cell. Murine embryonic fibroblast stained with (a) DAPI, (b) DAPI (blue) plus antibodies to fibrillarin (red) to mark nucleoli, and (c) antibodies to H3K9me3 (green) and fibrillarin (red). Abbreviations: PCH, pericentromeric heterochromatin; PH, peripheral heterochromatin; PNH, perinucleolar heterochromatin. Images are central planes from deconvolved 3D image stacks and are contrast enhanced to allow clear visualization of PH. Images from authors' laboratory.

Genomic Organization of Heterochromatin

Telomeric and Centromeric Regions Are Highly Condensed

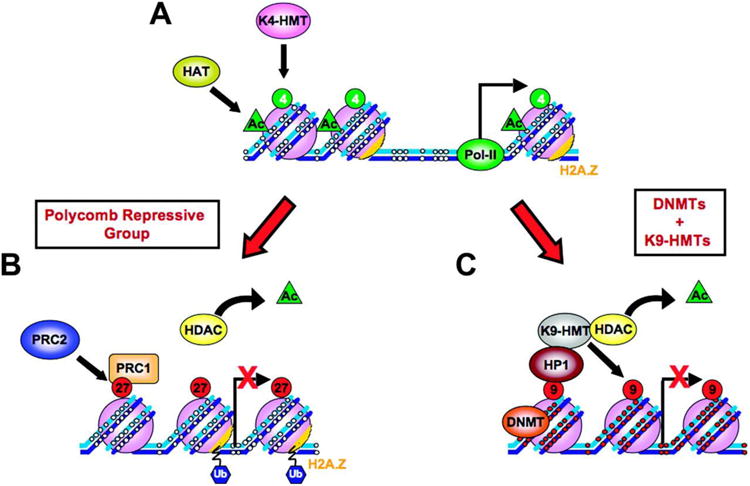

Telomeres, centromeres, and their adjacent silenced chromatin replicate in mid to late S phase and are highly condensed, constitutively repressed, highly repetitive regions that are DNAse I resistant, commonly marked with H3K9me3 and cytosine methylation at CpG dinucleotides (meCpG), and often bound by the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family of proteins (Figure 2). Telomeric DNA consists of tandem arrays of short, simple repeats (TTAGGG) at the ends of chromosomes (Schoeftner & Blasco 2008). Telomerase maintains these ends by catalyzing the addition of repeats at various times during the life of the cell (Egan & Collins 2012). A telomere position effect can silence transgenes inserted near telomeres (Gottschling et al. 1990), although some genes appear to cycle on and off (Kitada et al. 2012). Centromeric chromatin is highly compacted and was recognized as a primary constriction in the very early days of cytology (by Walter Flemming in the 1880s). These regions contain highly repetitive DNA and are marked by a centromeric protein (CENP), CENP-A in human, that replaces H3 in centromeric nucleosomes (Henikoff & Furuyama 2010). The sequence, length, and number of centromeric DNA tandem repeats and the composition of the adjacent heterochromatin vary among species, and, like other large repetitive regions in the genome, these regions are not well annotated. The combined pericentromeric and centromeric regions can be very large; for example, Martin et al. (2004) estimated that they comprise 10 of the 90 megabases on human chromosome 16. Pericentromeric DNA is known to contain TEs, simple repeats such as AATAT in Drosophila, 1--5-kb segmental duplications in primates, transfer RNA (tRNA) genes in some species, and a variety of other repeated sequences (Bailey & Eichler 2006, He et al. 2012, Partridge et al. 2000, Pidoux & Allshire 2005).

Figure 2.

Examples of repression in mammals. (a) An active chromatin structure and (b,c) examples of facultatively and constitutively repressed chromatin, respectively. (a) Unmethylated (small white circles) DNA (blue strands) wound around nucleosomes (purple balls) at an active DNA promoter region with RNA polymerase II (Pol II) bound at the nucleosome-free transcription start site. Active histone marks: acetylation (green triangle), H3K4 methylation (green circles), and high levels of H2A.Z on nucleosomes (orange). (b) Silencing via Polycomb repressive group proteins. PRC2 methylation of H3K27 (red circles, 27) is accompanied by deacetylation by histone deacetylase (HDAC, yellow oval), loss of H3K4 methylation, chromatin compaction, nucleosome occupancy at the transcription start site (red X indicates block to transcription), and PRC1 ubiquitinylation (blue hexagons, Ub) of H2A.Z. (c) Long-term silencing. Repressive H3K9 methylation (large red circles, 9, on purple nucleosome balls) at promoter regions recruits heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) and leads to silencing and chromatin compaction. DNA methylation at CpG sites (small red circles on blue DNA strands) is mediated by DNA methyltransferase (DNMT). DNA-methylated promoters show a depletion of H2A.Z, loss of H3K4 methylation, and histone deacetylation. In some cases, binding of DNMT is mediated by histone H1 (not shown) (Yang et al. 2013). Abbreviations: HAT, histone acetyltransferase; K4-HMT, histone H3 lysine 4 histone methyltransferase; K9-HMT, histone H3 lysine 9 histone methyltransferase; PRC1/2, polycomb repressive complex 1/2. Modified from Sharma et al. (2010) Carcinogenesis 31:27—36, with permission from Oxford University Press.

Facultative Heterochromatin Regions Are Flanked by Boundary Elements

Facultative heterochromatin is differentially repressed in various cell types and/or at particular times during development. It is often not as highly compacted as constitutive heterochromatin and contains distinctive marks and silencing proteins, such as polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs), that correlate with a particular type of repressed region (Figure 2). These regions are often flanked by boundary elements (BoEs), which are DNA/protein complexes, sometimes called insulators (Chung et al. 1993), that can cluster with one another and organize the intervening sequences into loops (Kellum & Schedl 1992, Yang & Corces 2012). The organization of regularly spaced BoEs may underlie the division of the mammalian genome into megabase, topologically associated domains (Dixon et al. 2012, Nora et al. 2012). BoEs include binding sites for CTCF, a well-characterized, highly conserved insulator protein (Wallace & Felsenfeld 2007); short interspersed element (SINE) retrotransposons; and tRNA genes. A portion of tRNA genes is always inactive and heterochromatinized (White 2011), and human tRNA genes can act as insulators (Raab et al. 2012). In fission yeast, some tRNA genes act as BoEs to partition particular regions within PCH (Partridge et al. 2000).

Another interesting genome looping element is SATB1 (special AT-rich binding protein 1), which binds particular ATC-rich BoEs in mammals. SATB1 binding at these regions anchors chromatin looping and mediates clustering of coregulated genomic regions during differentiation (Kohwi-Shigematsu et al. 2012) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Boundary elements and looping. (a) Diagram depicting potential chromatin-loop organization by SATB1. (top) Chromatin containing BUR (base-unpairing region) binding sites (red stars), exons from upregulated genes (orange and green boxes), downregulated genes (blue boxes), and genes that do not respond to SATB1 (gray boxes). (bottom) Proposed structure of SATB1 (turquoise ovals) binding to BURs at both upregulated and downregulated genes. SATB1 recruits histone acetylase p300 (dark blue oval) to activated gene loci and histone deacetylase HDAC1 (green oval) to repressed gene loci. From Kohwi-Shigematsu et al. (2012) with permission from Elsevier Ltd. (b) Model of chromatin loops (gold) anchored by gypsy insulator complexes (colored balls) clustered at the periphery in Drosophila nucleus. From Gerasimova et al. (2000) with permission from Elsevier Ltd. (c) Model depicting the role of the locus control region (LCR) in the localization of the chromosome territory (CT) containing the β-globin locus. (left) Wild-type β-globin locus on human chromosome 11 that has been transferred into murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells looped from its CT (CT11, dark orange) into the interchromosomal space (yellow). A 1 megabase region is looped along with the locus, and dashed lines represent unknown locations of chromatin linking the locus with the CT. (middle) The ΔLCR β-globin locus and the surrounding region remain restricted to the CT11 surface. (right) In the presence of the IgH LCR, the locus loops to the repressive pericentromeric heterochromatin (PCH) of an endogenous murine CT (green). Light-green and hatched regions represent nuclear periphery and lamina, respectively. Abbreviation: wt, wild type. From Ragoczy et al. (2003) with permission from Springer Verlag.

Under repressive conditions, the spatial clustering of BoEs can separate enhancers from promoters and move the looped regions to heterochromatic regions in the nucleus. The association of BoEs with chromatin remodeling proteins then modifies and condenses the intervening sequences into heterochromatin. For example, the Drosophila gypsy insulator has been shown to partition repressed DNA into loops anchored at the nuclear periphery (Gerasimova et al. 2000) (Figure 3).

Repressed chromatin flanked by gypsy and CTCF BoEs is often associated with the polycomb proteins (Figure 3). There are two main polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs) with multiple functions that bind to genomic polycomb response elements (PREs). PRC1 primarily ubiquitinylates H2A, and PRC2 primarily trimethylates H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) (Bantignies & Cavalli 2006) (Figure 2). Chromatin regions complexed with polycomb proteins cluster in the nuclei of diverse organisms (Bantignies et al. 2011, Tolhuis et al. 2011), and these clusters can associate with other heterochromatic regions (Wang et al. 2011). There is increasing evidence that specific long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), for example Xist and HotAir, direct PRC2 to specific genomic regions for remodeling and, along with certain small RNAs, are important for clustering (Grimaud et al. 2006, Brockdorff 2013). Polycomb bodies move dynamically within the nucleus and contain most of the H3K27me3 DNA in Drosophila embryos (Cheutin & Cavalli 2012). Regions flanked by CTCF BoEs and PREs can also be activated. For example, PRCs are replaced by trithorax binding at the PRE when Drosophila eye transgenes are activated and these regions then associate with other active genes (Li et al. 2013). The CTCF BoE is necessary for both repressive and active clustering.

Some BoEs, such as gypsy and CTCF, are TE derived (Schmidt et al. 2012), and TEs themselves, such as the previously mentioned SINEs in mouse and human, can serve as BoEs (Dixon et al. 2012, Ponicsan et al. 2010). Murine intracisternal A-particle retrotransposons have also been shown to induce heterochromatin formation (Rebollo et al. 2011). Most TEs are repressed and reside in constitutive heterochromatic regions, at least partly because if they become active inappropriately, illegitimate recombination between similar repeats ensues at the expense of genome integrity (Fedoroff 2012, Leung & Lorincz 2012). Potential functions for TEs in genome organization are just beginning to be understood, but the fact that the genes for many proteins involved in chromatin organization, including CENP-B and the gypsy integrase, appear to have been exapted from transposase genes (Chalopin et al. 2012) makes this area of research particularly fascinating. Indeed, the exapted transposase domain in Apb1, a member of the fission yeast CENP-B complex, is involved in both clustering and repression of Tf2 TEs in centromeric regions (Lorenz et al. 2012). It is likely that TEs play an important role in nuclear organization, both at the architectural level and during development, and more research in this area would be welcome.

Ribosomal RNA Gene Organization

Eukaryotic ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA) are organized into repeating arrays containing coding sequences for 28S, 18S, and 5.8S rRNAs embedded in substantial amounts of intervening sequences and spacers. These repetitive regions are mostly unannotated (Stults et al. 2008) and are located in nucleolar organizing regions (NORs) (McClintock 1934) near the telomeres on acrocentric chromosomes. In all eukaryotes studied, a fraction of the rDNA copies are heterochromatinized, and, at least in yeast and mouse, elimination of these silent copies affects genome stability (Guetg et al. 2010, Ide et al. 2010). The nucleolar remodeling complex (NoRC), which consists of TIP5 (TTF-1-interacting protein-5) and the ATPase SNF2h, competes with the activator, Cockayne syndrome protein B, to maintain this repression in mammals (McStay & Grummt 2008).

The repetitive genes for the fourth ribosomal RNA, 5S RNA, are linked to rDNA genes in yeast and some other eukaryotes; clustered at a few separate genomic sites in other organisms, such as Drosophila; and dispersed among many chromosomes in human (Haeusler & Engelke 2006). 5S genes (and pseudogenes) may also serve an organizing function as BoEs in mammals (Fedoriw et al. 2012).

Transcription of Heterochromatin

It has become clear in the past several years that most of the human genome is transcribed, albeit at very low levels for some regions (Djebali et al. 2012, Johnson et al. 2005). Transcripts arise from DNAse I sensitive, expressed regions, of course, but also from facultatively repressed regions and even constitutive heterochromatic regions, such as pericentromeric chromatin and telomeric DNA. At least three different kinds of transcription can occur in heterochromatic regions.

First, small RNAs can be transcribed and used to mediate epigenetic silencing. The transcription of small RNAs has been implicated in centromere silencing in yeast (Gent & Dawe 2012, Halic & Moazed 2010), and the piwi system regulates TE heterochromatinization in germ cells through the abundant TE-derived piRNAs (Aravin & Hannon 2008, Sienski et al. 2012). The long interspersed element-1 (LINE-1 or L1) TEs in human [which compose ∼17% of genome (Doucet et al. 2010)] are probably repressed via LINE-derived small RNAs (Yang & Kazazian 2006). Also, as mentioned above, polycomb-mediated repression involves transcription of small RNAs from polycomb target genes (Grimaud et al. 2006, Kanhere et al 2010). A slight variation on this theme is employed to silence rDNA loci. Small noncoding RNAs complementary to the rDNA promoter are transcribed from a region in the rDNA intergenic spacer (Mayer et al. 2008), and these interact with the NoRC and perhaps form a DNA:RNA triplex at promoters. This putative triplex may be recognized by a DNA methyltransferase that then methylates a crucial cytosine within the promoter to help inactivate the locus (Schmitz et al. 2010).

The second type of repressive transcription produces lncRNAs that often remain associated with their transcription site, although they can act in trans as well. This type of repression was first defined by the binding of Xist RNA to the X chromosome during inactivation (see Pollex and Heard 2012 for review). It is now clear that lncRNAs are transcribed from much of the mammalian genome but their function at most genomic loci is not well understood. They are known to be associated with imprinted genes, and, as mentioned, appear to be involved in targeting PRCs to specific genomic sites for chromatin remodeling (Lee 2012, Brockdorff 2013). LncRNAs are also transcribed from telomeric and centromeric repeats in mammals, but their role in silencing at these loci is somewhat unclear (Chu et al. 2011, Lu & Gilbert 2007, Schoeftner & Blasco 2008). Just the act of transcription may be sufficient for CENP-A binding and heterochromatinization, although the action of CENP-C, an essential linker between centromeric DNA and the kinetochore, is enhanced when bound to centromeric-complementary RNAs (Gent & Dawe 2012), which suggests that the RNA product(s) also may have a function.

A third type of transcription observed within the heterochromatic compartment arises from expression of DNAse I sensitive, active genes that are interspersed within heterochromatin. In yeast, several active protein-coding genes are tethered near nuclear pores (Brickner et al. 2012, Vodala et al. 2008), and some of these move from the silent PNH to the periphery for expression (Gard et al. 2009). Because yeast lack the nuclear lamin proteins and have only small amounts of heterochromatin compared with mammals, this may be a special case. However, even in other organisms, active genes sometimes lie within heterochromatic regions. A good example of this is Drosophila PCH or the green class of chromatin, where H3K9me2 and HP1 levels are high, but the region also contains transcribed genes (Filion et al. 2010, van Steensel 2011). Finally, it has also been shown that certain genes become transcriptionally activated while still in the PH. For example, when β-globin genes are activated in erythroid cells, transcription can begin before the gene moves away from the periphery (Ragoczy et al. 2006).

Spatial Organization of the Repressive Nuclear Compartment

PCH Loci (Chromocenters)

The composition of this heterochromatic region is in some ways the simplest to understand, because by definition, PCH loci contain centromeric and pericentromeric repetitive DNA. As mentioned earlier, PCH is AT rich and thus stains brightly with DAPI and Hoechst. In many organisms, centromeres cluster in nuclear bodies called chromocenters, and in organisms with telocentric chromosomes, such as mouse and cow, proximal telomeres cluster there also. Indeed, the region between the telomere and centromere on at least one murine chromosome contains an AT-rich retrotransposon repeat (tL1) (Kalitsis et al. 2006), which helps make mouse chromocenters especially brightly stained. In mouse, the patterns of bright DAPI stain and anti-H3K9me3 antibodies strictly overlap (Figure 1), but in cells where pericentromeric DNA is not as AT rich, such as human cells, it is helpful to stain PCH with CENP-A or H3K9 antibodies for better visualization of the loci.

The complete genomic composition of chromocenters or PCH loci has not been determined. Attempts to isolate these nuclear bodies have met with mixed success, because it is difficult to maintain their condensed state after nuclear lysis unless nonphysiological salt concentrations are used. However, it is clear from the few biochemical studies that exist (Zatsepina et al. 2008), and from many in situ hybridization studies and chromosome conformation capture (3C)-based experiments (de Wit & de Laat 2012), that not only is PCH from different chromosomes clustered together in these regions (Yaffe & Tanay 2011), but many repressed TEs (Dimitri 2004, Sun et al. 2003, Tanaka et al. 2012) and facultatively repressed genes (Clowney et al. 2012, Dernburg et al. 1996, Hewitt et al. 2009) also associate with PCH loci. In lymphocytes, for example, the transcription factor Ikaros can associate directly with pericentromeric repeats to tether repressed genes to PCH loci (Brown et al. 1999, Cobb et al. 2000).

PCH is often, but not always, associated with PH and/or PNH. In the simple case of budding yeast, centromeric regions from all 16 chromosomes are clustered together via microtubule tethering to the spindle pole body near the periphery (Taddei & Gasser 2012, Zimmer & Fabre 2011). In contrast, in human cells, it appears that location and degree of centromere clustering is both cell-type specific and cell-cycle dependent (see sections below). Centromeric regions are somewhat stationary and move only slowly during interphase in live yeast or human cells (Hubner & Spector 2010, Marshall et al. 1997).

Nucleolus and Perinucleolar Heterochromatin

Yeast has a single NOR and nucleolus, whereas metazoans have several NOR-bearing chromosomes that cluster into one or several nucleoli during active transcription of the rDNA repeats. Nucleoli are phase-dense, irregularly shaped nuclear bodies that stain intensely with RNA dyes and are the sites at which transcription, processing, and assembly of rRNA into ribosomes occur (Hernandez-Verdun 2006). Ribosomal RNA genes that are silenced by the NoRC are located in PNH. In situ hybridization experiments in multiple cell types have shown that PNH also contains centromeres and PCH from chromosomes with and without NORs (McStay & Grummt 2008). The essential centromeric binding protein, CENP-C, colocalizes in nucleoli with UBF (upstream binding factor), a regulatory protein that binds near the rDNA promoter (Pluta & Earnshaw 1996), demonstrating the close proximity of centromeric and ribosomal DNA. In situ hybridization has also shown that some facultatively repressed genes (e.g., Hewitt et al. 2008) preferentially localize to PNH and that telomeres, tRNA genes, and 5S rRNA genes cluster in this region in certain organisms (Fedoriw et al. 2012, Haeusler & Engelke 2006, Manuelidis & Borden 1988, Thompson et al. 2003). Further, Zhang et al. (2007) showed that the inactive X chromosome visits the repressive PNR environment during its heterochromatinization.

Nucleoli can be isolated fairly intact from purified nuclei, and genome-wide nucleolar-associated DNA sequences (NADs) have been identified by using massively parallel sequencing and microarray technology (Németh et al. 2010, van Koningsbruggen et al. 2010). In agreement with the earlier microscopy results, NADs included sequences linearly linked to NORs and sequences on other chromosomes throughout the genome. In one study where repeat sequences were identified, telomeric and centromeric DNA regions from multiple chromosomes were found in PNH, along with TE sequences and tRNA and 5S rRNA genes, which suggests that BoEs organize DNA with respect to the nucleolus (Németh et al. 2010). Additionally, loci that exhibit tissue-specific repression, such as olfactory receptor and immunoglobulin genes, were identified as NADs.

Knockdown of TIP-5, a member of the rDNA-silencing NoRC complex, disrupts not only rDNA locus organization but also PNH organization in murine cells (Guetg et al. 2010). This suggests that the accumulation of TIP-5-containing repressive complexes on inactive rDNA loci creates a microenvironment that affects the repression of spatially adjacent PNH. PNH disruption is also seen in Drosophila mutants that are missing the histone methyltransferase, Su(var)3-9. In this case, both H3K9me2 marks and the concomitant binding of HP1 are missing from PCH, and repeat DNA in general becomes unstable and shows increased recombination (Peng & Karpen 2009). Because even artificial HP1 tethering initiates H3K9me3 spreading that is heritable over multiple generations in mammalian fibroblasts (Hathaway et al. 2012), the Su(var)3-9 Drosophila mutants may disrupt a feedforward loop critical for heterochromatin maintenance. The nucleolus thus serves not only as the site of ribosome synthesis in the cell but also as a critical heterochromatin organizing center, where centromeres, pericentromeric chromatin, tRNA genes, and facultative heterochromatin from multiple sites on many chromosomes congregate and are heritably repressed (Gilbert & Gasser 2006, van Steensel & Dekker 2010).

The nucleolar entities that mediate chromatin clustering within the PNR are just beginning to be identified. It has been known for some time that CTCF-mediated binding of c-myc to the nucleolar periphery in HeLa cells requires interaction with the nucleolar protein, nucleophosmin (Yusufzai et al. 2004), and that nucleophosmin also binds to centromeres in Drosophila (Foltz et al. 2006). Recently, Padeken et al. (2013) have brought these somewhat divergent observations together to show that Drosophila centromeres are clustered via both CTCF and a Drosophila nucleophosmin homologue, but are are tethered to the nucleolus by the nucleolar protein, nucleolin. LncRNAs may also be involved in tethering chromatin to the PNR. For example, the lncRNA Kcnq1ot1, which interacts with both chromatin and methyltransferases in placenta, colocalizes with the nucleoli when silencing the Kcnq1 imprinted region (Pandey et al. 2008).

The Nuclear Periphery and Peripheral Heterochromatin

Both telomeres and centromeres are peripherally localized in yeast, which do not have a classical lamina. Telomeres are concentrated in clusters of PH via the Sir2/3/4 (silent information regulator 2/3/4) and Yku70/80 (yeast Ku70/80) pathways, and peripheral anchoring can be uncoupled from silencing (Taddei & Gasser 2012). Yeast centromeres are clustered at the periphery via tethering to the spindle pole body at the end of the nucleus opposite from the nucleolus, as mentioned. We discuss the consequences of these localizations to the global organization of the yeast genome later.

PCH loci and sometimes telomeres also localize at the periphery in metazoans. Lamins, which are type V intermediate filament proteins, line the inner nuclear membrane in metazoans, creating a dynamic structural network that interacts with chromatin (Dechat et al. 2008). Lamins form two families, lamins A/C and lamin B, and the particular composition of the lamina varies among cell types and during development. Both A- and B-type lamins are important for peripheral tethering of heterochromatin, but lamin A/C expression is developmentally regulated, whereas lamin B is expressed in most cells (Burke & Stewart 2013). Lamin B receptor (LBR) is expressed in undifferentiated cells and can substitute for lamin A (Solovei et al. 2013). A-type lamins bind to mitotic chromosomes and also interact with interphase chromatin both directly and indirectly, via lamin- and chromatin-binding proteins. For example, LAF2α, a lamin A/C binding protein, has been shown to bind to telomeres during G1 (Dechat et al. 2004), and LEM-2, another lamin A/C binding protein, tethers heterochromatic chromosome arms to the nuclear periphery in Caenorhabditis elegans (Ikegami et al. 2010). Another nuclear envelope protein, emerin, has been shown to bind histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) at the periphery (Demmerle et al. 2012). Deacetylation is one of the first steps in heterochromatinization, followed by methylation at H3K9 (see Figure 2).

Various mutations in the lamins and lamin-binding proteins cause loss of PH and reduction of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 marks in both human and mouse (Butin-Israeli et al. 2012, Dechat et al. 2008). The human premature aging disease, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria, is caused by a mutant form of lamin A (progerin) that does not incorporate properly into the nuclear lamina. In these cells, the nucleus is lobulated, and heterochromatin loses its distinctive marks and no longer associates with the periphery (Dechat et al. 2008, Kubben et al. 2012). Somewhat similarly, lamin A and LBR mouse double knockouts lack PH and instead display internalized heterochromatin in an inside-out arrangement (Solovei et al. 2013). However, in these mutants, it does not appear that repressive marks are lost. Ectopic expression of lamin A or LBR (which is expressed in place of lamin A in undifferentiated cells) can rescue the inverted phenotype, and PH returns. Also, when a hypomorphic allele of the single Drosophila lamin gene is expressed, it disrupts clustering of gypsy insulator sites and reduces tethering to the periphery (Capelson & Corces 2005), again demonstrating the important role that lamins play in peripheral tethering of heterochromatin. This homozygous lamin mutant dies at the third instar larval stage.

When HDAC3 is knocked out in mice, most PH is also lost (Bhaskara et al. 2010). This deletion also affects DNA repair and replication, so it is difficult to parse out specific effects on peripheral localization of heterochromatin. However, as mentioned, another nuclear envelope protein, emerin, binds HDAC3 at the periphery. When emerin was knocked down using siRNA in C2C12 mouse myoblasts, neither HDAC3 nor heterochromatin associated with the periphery (Demmerle et al. 2012), which suggests at minimum that the presence of HDAC3 is necessary for PH maintenance. Thus, multiple mutants show that the lamins and their binding proteins are necessary for the proper peripheral association of heterochromatin in differentiated cells.

In a few cases, the DNA sequences necessary for peripheral association have been defined. In murine fibroblasts, where the IgH gene is peripherally localized and repressed, Zullo et al. (2012) found that a GAGA-rich repeat is sufficient for tethering. The GAGA motif interacts with cKrox, which binds both HDAC3 and LAP2β (lamin-associated protein 2β), presumably to anchor the sequences to the lamina (Zullo et al. 2012). If cells are treated with trichostatin A, a specific histone deacetylase inhibitor, the locus no longer associates with the periphery, and, importantly, this effect is reversible. Thus, although the effects of deacetylase knockdown by drugs (or genetics, as mentioned previously) are pleiotropic, this result suggests that both the action of HDAC3 and its association with the inner nuclear membrane are necessary for initial tethering and maintenance of peripheral localization of the IgH locus in fibroblasts. It would be interesting to know whether the trichostatin A treatment also caused activation of the locus when it moved away from the periphery.

Ottaviani et al. (2009) showed that a polycomb-binding tandem repeat, D4Z4, was also sufficient for peripheral tethering via lamin A and CTCF in human cells. This subtelomeric region on chromosome 4 contains multiple repeats in wild type but is contracted in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. When the number of repeats is reduced to 10 or less, this region no longer associates with the periphery, polycomb binding is lost, and the region becomes active (Cabianca et al. 2012). A dominant deleterious product, DUX4, is then expressed in patients who carry particular single-nucleotide polymorphisms (Lemmers et al. 2010). It has not been shown whether the contracted repeat region would be silent if artificially tethered to the periphery, so it is unclear whether association with the periphery alone or polycomb binding to the multiple wild-type repeats (and resultant repressive modifications) is the repressive driver in this case. Nevertheless, transcription occurs only on the truncated locus away from the periphery.

The genomic distribution of lamin B1--associated chromatin domains (LADs) has been determined in human fibroblasts and ES cells and in differentiating mouse ES cells (Guelen et al. 2008, Peric-Hupkes et al. 2010, Meuleman et al. 2013). LADs are primarily heterochromatic AT rich regions and include centromeric and telomeric sequences and many developmentally repressed loci, but also some H3K4me3-marked chromatin that is presumably unrepressed. Centromere clustering has been confirmed in HiC experiments (Imakaev et al. 2012, Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009, Yaffe and Tanay 2011), and peripheral localization has been confirmed in in situ hybridization experiments (Solovei et al. 2004). This brings up an important methodological point. Although lamins do not diffuse with the rapid kinetics of most nuclear proteins, they are not immobile proteins. Type-A lamins remain predominantly in the nuclear interior in early G1, but both lamin types are present in low levels in the nucleoplasm throughout the cell cycle (Dechat et al. 2008). Therefore, proximity to lamin B suggests but does not prove that a particular sequence is peripheral, and LAD localization by in situ hybridization or cell fractionation experiments is needed to confirm binding to the periphery.

As in the perinucleolar region, the concentration at the nuclear periphery of heterochromatin and its requisite remodeling proteins is thought to create a primarily repressive environment. Consistent with this idea, when exogenous repetitive DNA sequences move to the periphery in C. elegans, surrounding endogenous euchromatin is often silenced in concert (Meister et al. 2010). Similarly, when chromosomes are artificially tethered to the periphery in mammalian cells, genes close to the tethering site are often silenced (Finlan et al. 2008, Reddy et al. 2008). However, as mentioned, telomere silencing can be uncoupled from peripheral localization in budding yeast, where the local concentration of the repressive Sir proteins is the determinative silencer (Taddei et al. 2004, Taddei et al. 2010). Also, it is possible to induce transcription of exogenous sequences tethered to the periphery in mammalian cells (Kumaran & Spector 2008). It is also clear that active genes localize near nuclear pores in yeast (Taddei et al. 2010) and that the murine β-globin gene can be transcribed before it leaves the periphery during erythropoiesis (Ragoczy et al. 2006). Thus, although the bulk of the periphery is occupied by heterochromatin, the detailed organization and subcompartmentalization of this region are not well understood and remain an area of active study.

Heterochromatin Self-Association

Although, as discussed, some specific components that tether heterochromatin within silencing regions have been identified, it is likely that heterochromatin self-association is an additional driving force in the formation and maintenance of the silencing compartment. The tendency of repressed chromatin to cluster together has suggested a “birds of a feather flock together” model where heterochromatin self-association drives global separation of the silencing compartment from the active, euchromatic compartment (e.g. see Gibcus and Dekker, 2013). Such a model suggests that heterochromatin might associate equally well with any of the three repressive regions discussed and indeed, experiments that study the redistribution of LADs and NADs from mother to daughter cells partially support this notion. We discuss those results within the context of the next section.

Changes in Heterochromatin Organization During Cell Cycle and Development

We begin this section with a methodological note. Changes in 3D positioning of heterochromatin are primarily assayed at the single-cell level by immunostaining and in situ hybridization with probes to particular regions and/or chromosomes, or at the population level by 3C-based methods. It is clear from single-cell studies using chromosome paints, which stain the unique regions of a particular chromosome, that although individual chromosomes are confined within loose territories, the 3D juxtaposition of territories is not fixed in one reproducible distribution between cells. Rather, there exist preferred distributions within a particular cell type or developmental period (Cremer & Cremer 2010, Mayer et al. 2005, Neusser et al. 2007, Rajapakse et al., 2009). The same holds true for single genes---genes may be enriched in a particular subnuclear region, but a gene rarely behaves the same in every cell, even in clonal populations. This stochastic behavior extends to gene expression as well (Noordermeer et al. 2011, Misteli, 2013). In situations where visualization of locus distribution in individual cells is not needed, 3C-based methods allow genome-wide proximity mapping in different cell populations.

Heterochromatin Behavior During the Cell Cycle

Even though heterochromatin is highly condensed and compartmentalized, it is far from static. Indeed, the repressive compartment must disassemble, replicate, undergo mitosis, and then recoalesce daily in rapidly growing cell populations. In mouse and human, transcription of rRNA resumes in telophase. Prenucleolar bodies and active NORs first cluster into small, nascent nucleoli (Hernandez-Verdun 2006). These nascent nucleoli are small and numerous, but they quickly fuse with one another by early G1 to form fewer, larger nucleoli with prominent PNH. Nucleolar fusion events may occur over micrometers, scaling to very large ranges within the nuclear space, and this process likely reorganizes chromatin. The number of nucleoli in daughter cells from the same mother is often different, even in primary cell lines, and when the chromatin in an individual PNR is photoactivated (using Dendra-H4, which diffuses very slowly) in transformed cell lines, it is found distributed among the PNH at multiple nucleoli after mitosis (Cvačková et al. 2009). Much of this chromatin is linked to NORs, so nucleolar association is to be expected, but these results suggest that although heterochromatin maintains its compartmentalization across cell division, individual regions do not mirror their 3D positioning in daughter cells.

In early G1, centromeres and their proximal PCH are still located in the nuclear interior in mammals, and their individual locations may partially reflect their preferred positioning during anaphase (Solovei et al. 2004). Chromosomal positioning in the prometaphase rosette can in turn reflect interphase proximity in mouse (Gerlich et al. 2003, Kosak et al. 2007). Most centromeres then move to the periphery and cluster into PCH loci during late G1, although some remain internalized and associate with nucleoli (Solovei et al. 2004). Telomeres also cluster into many groups during late G1, but most remain internal in human cells, whereas in mouse, with its telocentric chromosomes, many are associated with peripheral chromocenters (Weierich et al. 2003). Also during late G1, lamins, which have coated chromosomes during mitosis and remain internal during early G1, begin to recoat the inside of the reformed nuclear envelope (Dechat et al. 2008), and the interphase compartmentalization of heterochromatin is realized.

In late S phase and G2, centromere clusters break apart, centromeres move back to the interior and homologs approach each other, presumably in preparation for mitosis (Brero et al. 2005, Weierich et al. 2003). rDNA also moves from the nucleolar interior to the nucleolar periphery for replication late in S phase in mammals (Dmitrova 2011), and the nucleolus breaks down. As the nuclear envelope begins to break down at the beginning of the next mitosis, lamins again coat chromosomes, and a new metaphase plate is formed.

The mechanisms driving the global changes in centromere and telomere distribution and clustering over the cell cycle are not well understood. However, it should be noted that diffusion of these regions is constrained to a higher degree than in euchromatic regions in early G1, especially in yeast, where both centromeres and telomeres remain associated with the nuclear periphery throughout the cell cycle (Heun et al. 2001, Hubner & Spector 2010). Interestingly, in fission yeast, long terminal-repeat TE clustering at centromeres is disrupted during the cell cycle via replication-coupled H3K27me3 acetylation in S phase (Tanaka et al. 2012). Ku and condensin no longer bind the long terminal repeats, and the clusters fall apart in preparation for mitosis. Furthermore, clustering of Tf2 TEs is mediated by CENP-B proteins in fission yeast.

Notably, it appears that newly repressed genes require progression through the cell cycle to establish their silencing. In T lymphocytes, the movement of Ikaros-associated genes to the PCH loci occurs only after mitogenic stimulation (Brown et al. 1999), and association of ectopic sequences with the nuclear periphery in cultured cells requires cell division (Kumaran & Spector 2008, Reddy et al. 2008). Zullo et al. (2012) also showed recently that lamin B1 reassociates with the IgH GAGA LAD motif during early G1 and that ectopic LAD sequences must go through mitosis before peripheral association occurs. This suggests a model where heritably repressed genomic regions associate with organizing factors that seed heterochromatic compartment reorganization early in G1. In support of this interpretation, polycomb and other insulator proteins remain bound to chromatin domain borders during mitosis (Follmer et al. 2012), which suggests these boundary domains could act as hubs for reorganization after mitosis.

However, any re-seeding that occurs does not result in daughter cells that are identical to mother cells. As mentioned, PNH re-sorts between nucleoli after mitosis and LADs appear to redistribute between both PH and PNH after mitosis. van Koningsbruggen et al. (2010) have shown that PH marked with photoactivated GFP-histone H2 was equally likely to be associated with the PH or PNH after mitosis, and Kind et al (2013) have recently used a more targeted method, where specific lamin-interacting DNA sequences are labeled in mother cells, to show that although some LADs return to the periphery after mitosis, a portion instead associate with the nucleolus and a small number appear to become nucleoplasmic in daughter cells (although PCH was not labeled in these experiments). Thus, PH re-sorts not only within but between repressive regions after mitosis, suggesting that these two spatial subcompartments provide similar repressive environments.

Seeding and growth of heterochromatin regions occurs in early G1 while chromatin location is still fluid and contact between highly repetitive regions occurs more often than between non-repeats, thus favoring self-association of heterochromatic regions. This is consistent with the birds-of-a-feather-flock together model, where self-association is a driver for heterochromatin re-formation. Additionally, highly repetitive sequences (e.g. silent rDNA, pericentromeric repeats and lamina-associated repeats) may act as dominant seeds to concentrate any nearby heterochromatin into the PNR, PCH loci and PN during reorganization in early G1. This seeding model has been called a dog-on-a-leash model, where the highly repetitive sequences act as dominant bulldogs to pull its owner (the chromosome) to particular locations while submissive dogs on other leashes (non-repetitive sequences) are pulled along for the ride (Krijer and DeLaat, 2013).

Heterochromatin Formation in Early Development

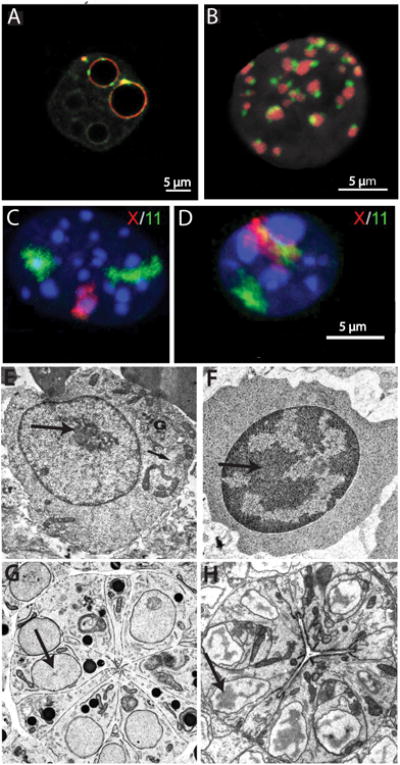

Mammalian zygotes contain little methylated DNA or highly condensed heterochromatin (even PCH decondenses somewhat after fertilization). Almost all chromatin, including TEs, is transcribed at some level (Efroni et al. 2008, Macfarlan et al. 2012, Reik et al. 2001). This is thought to be a reflection of the so-called totipotent state, which allows a zygote to differentiate into multiple cell types. PCH (containing H3K9me3) is known to coat prenucleolar bodies (collections of ribosomal RNAs and processing proteins) in mouse zygotes, especially in the maternal pronucleus, but there is virtually no heterochromatin associated with the periphery, and no chromocenters are visible (Ferreira & Carmo-Fonseca 1997, Martin et al. 2006) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in heterochromatin distribution during development. (a) Single confocal section of mouse preimplantation embryo at early 2-cell and (b) 16-cell stage showing distribution of pericentromeric (red) and centromeric (green) chromatin. DNA is gray. Reprinted from Aguirre-Lavin et al. (2012). (c) Maximum-intensity 3D projections of mouse primary myoblast and (d) myotube showing DNA distribution (blue) and locations of chromosomes X (red) and 11 (green). Reprinted from Mayer et al. (2005). (e-h) Electron micrographs showing change in heterochromatin distribution (arrows) during differentiation. (e) Murine proerythroblast and (f) late erythroblast. Reprinted from Francastel et al. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1: 137—43, with permission from Nature Publishing Group. Caenorhabditis elegans pharyngeal primordium in embryo (g) at the commitment stage and (h) in late embryogenesis after terminal differentiation. Reprinted from Leung et al. (1999) with permission from Elsevier Ltd.

Early after the first cell division in mouse, a burst of pericentric transcription is coordinated with the clustering of centromeres away from prenucleolar bodies and into chromocenters (Probst et al. 2010). Ribosomal RNA transcription begins at the mid-late two-cell stage, and the active rDNA genes associate with nucleolar prebodies to form nucleoli (Aguirre-Lavin et al. 2012, Romanova et al. 2006).

Simultaneously, differential histone methylation begins (Lessard & Crabtree 2010), and heterochromatin begins to appear at the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al. 2010, Ferreira & Carmo-Fonseca 1997). Murine double knockouts of the two de novo DNA methyltransferases (DMNT3a and DMNT3b); HDAC1; or the histone mono- and dimethylase, G9a, are early embryonic lethal, which suggests that the wave of heterochromatinization that begins in two-cell embryos is necessary for differentiation (Lagger et al. 2002, Okano et al. 1999, Tachibana et al. 2002). Notably, the ubiquitous lamin B is the only lamin present in embryos, and it may be dispensable in early development (Burke & Stewart 2013). When lamin A is ectopically expressed in ES cells, mobility of the histone H1, which can be involved in heterochromatin condensation (Yang et al. 2013), is reduced, consistent with the observation that lamin A-containing differentiated cells contain higher levels of heterochromatin (Melcer et al. 2012).

Heterochromatic Changes During Cellular Differentiation

The repressive compartment often changes form and composition during development. Figure 4 shows two examples, during murine erythropoiesis and organogenesis of the C. elegans pharynx, where the amount of heterochromatin increases dramatically and massive reorganization occurs during terminal differentiation. Reorganization also occurs during terminal differentiation in both muscle and brain, where chromocenters fuse and become internalized (Brero et al. 2005, Manuelidis 1984) (Figure 4). This fusion has been linked to the presence of meCpG marks and increased levels of the meCpG-binding protein, MeBP2, in PCH (Brero et al. 2005, Singleton et al. 2011). Heterochromatin rearrangements can also occur without changes in repressive marks. For example, during aging in human fibroblasts, senescence-associated heterochromatic foci (H3K9me3 positive centers surrounded by a ring of H3K27me3 heterochromatin) form in the absence of detectable changes in such marks (Chandra et al. 2012).

An intriguing global rearrangement of heterochromatin occurs during terminal differentiation of rod photoreceptor cells of nocturnal animals (Solovei et al. 2009). Here the nuclear chromatin organization is inside out, as PH is internalized and euchromatin and nucleoli move to the periphery (Figure 5). This rearrangement allows columns of rod cells to channel light more effectively as actual diffracting lenses and results from the downregulation of both lamin A and LBR (Solovei et al. 2013). This inside-out nuclear arrangement is also seen in the lamin A and LBR double-knockout mice discussed earlier (see The Nuclear Periphery and Peripheral Heterochromatin, above). All mouse cells studied, except rods, contain PH and most express LBR early in development and lamin A during terminal differentiation. Interestingly, lymphocytes, which do not switch to lamin A/C expression during differentiation but rather maintain LBR throughout their lifetime, show the inside-out phenotype in LBR knockdown mice (Solovei et al. 2013).

Figure 5.

Reorganization of heterochromatin in rod cells. (Top row) In situ hybridization showing progression of heterochromatin internalization during terminal differentiation in rod cells. Numbers indicate days after differentiation begins, with the rightmost image number indicating months. Heterochromatin (red), euchromatin (green), and chromocenters (blue) are shown. (Bottom row) Model depicting possible organization of euchromatin and heterochromatin before and after differentiation. Light gray regions represent nuclear heterochromatin and white regions, nuclear euchromatin. Adapted from Solovei et al. (2009) with permission from Elsevier Ltd.

Another interesting relocalization occurs with the olfactory receptor genes. In this system, only one of ∼2,800 receptor genes is expressed per olfactory sensor neuron. As the neurons develop, this gene becomes associated with a distant enhancer and is activated, whereas the remaining receptor genes, which are scattered on many chromosomes, are repressed and cluster with one another into heterochromatic foci that associate with PCH (Clowney et al. 2012). At the same time, LBR synthesis is downregulated in these cells, and global heterochromatin becomes concentrated in the interior rather than at the periphery, somewhat resembling the inside-out architecture of the retinal cells described above. This rearrangement can be rescued by ectopic expression of LBR. Nucleoli were nt stained in this study, but it is perhaps of note that olfactory receptor genes were identified as NADs in the nucleolar association studies discussed earlier (Németh et al. 2010, van Koningsbruggen et al. 2010), albeit in vastly different cell types. Large internal PCH foci are also observed in many neuronal populations besides olfactory sensory neurons in the ichthyosis mouse, where LBR is knocked down (Goldowitz & Mullen 1982). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that lamin A and LBR are integrally involved in PH tethering during development.

Gene loci that associate with the heterochromatic compartment only when repressed (Joffe et al. 2010, Jost et al. 2012, Lanctot et al. 2007) are particularly interesting. One of the earliest and most intriguing observations of this type was the behavior of the brownDominant mutation in Drosophila: The insertion of 1--2 kb of heterochromatin into the brown coding region resulted in the silencing and mislocalization to PCH of not only the mutant allele but also the wild type allele on a somatically paired homologous chromosome (Csink & Henikoff 1996, Dernburg et al. 1996). Well-studied examples in mammals come from hematopoietic development. During mouse thymocyte maturation, Rag and Dntt loci move to associate with PCH loci in a process mediated by the zinc-finger DNA-binding protein, Ikaros (Brown et al. 1999). The kinetics of this process have been characterized in some detail. Early after stimulation of thymocyte maturation, Ikaros competes with the activator Ets for Dntt promoter binding and suppresses transcription. The Ikaros-bound gene, with or without an associated HDAC complex, then moves to a PCH locus, where Ikaros may form multimers linking the gene to PCH α-satellite repeats (Trinh et al. 2001). Relocation of Dntt to PCH loci peaks at 30 min after stimulation, and deacetylation follows for 2--6 h. H3K4 demethylation and, finally, histone methylation (antibodies did not distinguish between di- and trimethylation of H3K9 and H3K27me3) and spreading (at a rate of approximately 2 kb/h) occur at 6--18 h, and the locus becomes irreversibly repressed (Su et al. 2004). Although gene movement appears to precede histone mark changes in this case, there is still some uncertainty, because Ikaros can also associate with active genes (Zhang et al. 2012).

Conversely, IgH and IgK genes are preferentially located at the periphery and repressed in hematopoietic progenitors (Kosak et al. 2002). All four genes then move to the interior, and recombination occurs at one allele of each gene in pro-B cells. These alleles then remain expressed and undergo further recombination, whereas the nonrecombined allele of each gene is again repressed but now moves to PNH (Hewitt et al. 2009). CTCF-mediated looping is involved in VDJ recombination and, although this has not been shown, it could also be involved in the epigenetic repression of this region (Phillips & Corces 2009). Like IgH and IgK, the β-globin gene associates with the periphery in hematopoietic progenitors but then begins transcription, and both alleles move inward into euchromatic regions during erythrocyte development (Ragoczy et al. 2006). The locus control region (LCR), which contains CTCF and transcription factor--binding sites, is necessary for this movement. Interestingly, when an IgH LCR (which also contains CTCF and transcription factor binding sites) is inserted in place of the β-globin LCR in murine erythroleukemic cells, the entire globin locus loops out to a repressive PCH locus, presumably owing to a switch from coactivators binding the globin LCR to corepressors binding the IgH LCR in this cellular background (Brand et al. 2004, Ragoczy et al. 2003) (Figure 3).

Another looping element previously discussed, SATB1 (Figure 3), has been shown to facilitate differentiation in mammalian embryonic stem cells, erythrocytes, thymocytes, and epidermal cells and affects repression as well as activation (Kohwi-Shigematsu et al. 2012). For example, SATB1 recruits HDAC1 and chromatin remodeling enzymes to the IL-2Rα locus during its inactivation in thymocyte maturation (Yasui et al. 2002). Work is underway to identify the tissue-specific regulators that are predicted to interact with SATB1 and other BoEs and insulators and confer cell-type specificity on nuclear organization during development. Recently, Matzat et al. (2012) found that increased levels of a newly identified polycomb-binding protein, Shep, substantially reduce interactions between gypsy insulator sites and remodel nuclear organization specifically in Drosophila neurons, which suggests that such tissue-specific regulators will be identified in more cell types in the future.

Does Heterochromatin Formation Drive Overall Nuclear Organization?

As we have discussed, heterochromatin formation and compartmentalization are required very early in development and are crucial for differentiation, consistent with an important role in the global organization of chromatin in the nucleus. But can heterochromatin formation and compartmentalization seed the organization of an entire genome in 3D space? We first consider the special case of budding yeast, where recent 3D genome-organization modeling studies have come to some interesting conclusions.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae nucleus is approximately tenfold smaller than the nucleus of higher eukaryotes, has no classical lamins, and its single nucleolus is tethered to the nuclear envelope via its heterochromatic rDNA repeats (Mekhail et al. 2008). Telomeres cluster in caps at the periphery, whereas centromeres cluster near the spindle pole body at the end opposite from the nucleolus, giving the yeast nucleus longitudinal polarity. This is very important for orientation during studies where genome organization is modeled. Additionally, the yeast's 274 tRNA genes cluster in two groups, one near the congressed centromeres and one near the nucleolus (Duan et al. 2010, Thompson et al. 2003, Wong et al. 2012). These tRNA genes, or their associated Ty1 retrotransposon sequences (O'Sullivan et al. 2009), likely act as BoEs to anchor chromatin loops near the nucleolus, and notably, early replication origins also may act as BoEs in yeast (Duan et al. 2010).

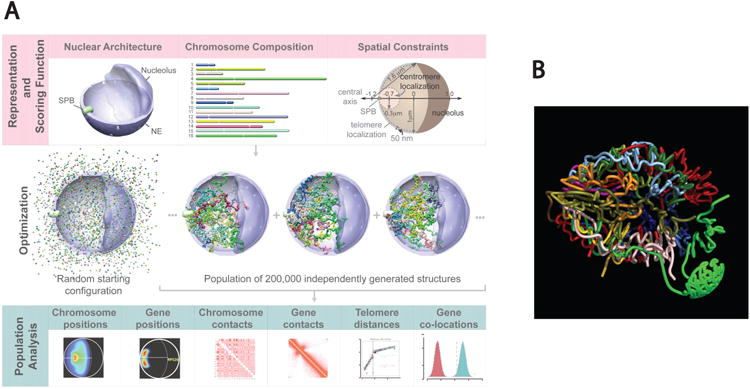

Interestingly, theoretical 3D genome-modeling studies can predict the probabilistic disposition of the 16 yeast chromosome territories within the nuclear space. These studies employ rules of volume exclusion, molecular crowding, and generic polymer effects coupled solely with known heterochromatic tethering sites (telomeres, centromeres, and sometimes rDNA) as initial parameters (Gehlen et al. 2012, Tjong et al. 2012, Wong et al. 2012) (Figure 6). All models are probabilistic and predict the distribution of 3D organizations within a population. Remarkably, these theoretical models predict the clustering of tRNA genes and also association of early replication origin sites. Additionally, all predict the crescent shape of the single nucleolus attached to the nuclear envelope and the distribution of distances between loci observed in situ. Simple clustering of centromeres at the spindle pole body sorts chromosomes according to size by volume exclusion effects---smaller chromosomes tend to fit closer to the tethering site. This sorting is then envisioned to determine the probabilistic spatial organization of each chromosome with respect to the others and, together with telomere tethering and nucleolar exclusion, affect chromosomal interaction frequencies in specific ways (Tjong et al. 2012). Thus, yeast nuclear organization can be predicted to a remarkable extent simply by modeling the effects of the clustering of various heterochromatic regions and their tethering to the nuclear envelope, as had been proposed earlier (O'Sullivan et al. 2009, Taddei et al. 2010). Importantly, if tethering of the heterochromatic components is not included as a parameter, the models fail to predict the observed associations between tRNA genes or other genes that preferentially colocalize (Gehlen et al. 2012, Wong et al. 2012). This strongly suggests that clustering of the heterochromatic regions is the driver of nuclear organization. In this context, it would be interesting to see whether modeling studies could predict the nuclear organization of particular yeast mutants, such as the double mutant yku70 esc1, that disrupt telomere anchoring and clustering (Taddei et al. 2009).

Figure 6.

Modeling the genome of budding yeast in 3D. (a) Population-based analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome organization. (Top panels) Structural representation of nuclear architecture (left), chromosomes as flexible chromatin fibers (center), and the scoring function quantifying the accordance of genome structure with nuclear landmark constraints (right). (Middle panels) An optimization and sampling method that minimizes the scoring function to generate a population of genome structures that satisfies landmark constraints. (Bottom panels) Statistical analysis and comparison of structural features from the population of 3D genome structures with all the experimental data. Figure reprinted from Tjong et al. (2012). Abbreviations: NE, nuclear envelope; SPB, spindle pole body. (b) Empirical model based on genome-wide, chromosome conformation capture--based data and known heterochromatic tethering sites. Each color represents a different chromosome. From Duan et al. (2010) with permission from Nature Publishing Group.

Although it has not yet been possible to predict the arrangement of chromosomes in the much larger mammalian nucleus, one can still draw some conclusions regarding the role of heterochromatin formation in mammalian nuclear organization. One would expect that if heterochromatin formation seeds nuclear organization, blocks to heterochromatin formation would disrupt disposition of both heterochromatic and euchromatic sequences and interfere with global gene expression and regulation of development. As we have discussed, in mammals, heterochromatin formation begins in the two-cell embryo, and murine knockouts of most of the de novo repressive modification enzymes are embryonic lethal (Lessard & Crabtree 2010). Even alterations to maintenance enzymes, such as knockdowns of DMNT1, the maintenance DNA methyltransferase that can associate with HDACs, are often embryonic lethal. Knockouts of HDAC3 also cause loss of PH and promiscuous expression of formerly repressed genes. Another convincing example in this regard is the TIP5 knockdown experiment discussed earlier. TIP5 is part of the NoRC complex, which induces de novo methylation of rDNA genes, thus seeding heterochromatinization (Santoro et al. 2002). Loss of TIP5 in mice caused not only silent rDNA genes but also centromeric and pericentromeric DNA to lose their repressive histone marks and become acetylated, and thus, gross PHC and PNR organization was disrupted (Guetg et al. 2010). Additionally, downregulation of TIP5 was associated with an increase in active rRNA transcription and the transformed cell-growth phenotype. Similarly, the disruption of PCH caused by depletion of the Drosophila nucleophosmin homologue (or CTCF), discussed earlier as a mediator of centromere clustering, allows promiscuous transcription of TEs and other silenced repeats, resulting in genome instability (Padeken et al. 2013). In summary then, repressive compartment organization and genome integrity is mediated, at least in part, by single proteins involved in seeding heterochromatinization in mammalian cells.

These results support the notion that heterochromatin formation and compartmentalization are drivers of nuclear organization in mammalian cells. However, we do not know to what extent the particular organization of centromeres, telomeres, and repetitive sequences within the repressive compartment affect global nuclear organization, and to what extent such particular organization persists through successive cell divisions. As discussed, many differentiated mammalian cell types and tissues show at most a preferred or probabilistic nuclear organization, evidenced most simply by the fact that the number of nucleoli is not inherited in many cells types. Clearly, it would be useful to theoretically predict a preferred spectrum of 3D nuclear organizations for a particular mammalian cell type based solely on the positions of heterochromatic elements, as done in yeast. However, in contrast to yeast, mammalian modeling studies are much more difficult owing to the large and ill-defined number of tethering sites involved, as well as the presence of much larger chromosomes situated in a much larger nucleus.

Perspectives and Future Work

There are several areas where our knowledge is deficient with respect to heterochromatin formation and function. First and foremost, the annotation of repetitive DNA sequences is quite incomplete. This includes the rDNA genes and much of the pericentric regions and centromere sequences. Even if annotation continues to proceed slowly, 3C-based methods can now include analysis of repetitive sequences due to technical advances in next generation sequencing (Alexander et al. 2010). A related issue is the annotation and 3D localization of TEs in the human genome. In organisms with compact genomes, TEs often cluster in pericentromeric or peritelomeric regions (Dasilva et al. 2002, Tanaka et al. 2012). In contrast, human Alu sequences appear to be dispersed throughout the nuclear space (Bolzer et al. 2005), and it remains unknown how the majority of the ∼50% of the genome made up of TEs contributes to nuclear organization in humans.

Next, to learn more about nuclear organization at high resolution and map the location of genes and chromosomal domains, we need to span the gap between single-cell in situ hybridization and 3C-based experiments that measure population averages. One way to bridge this gap is to automate multiplex in situ hybridization analysis, so that single-cell information can be integrated with population averages. Superresolution bar coding may be one way to address this issue (Lubeck & Cai 2012). This approach may help us to better understand why different cells within a synchronized, clonal population can have different 3D chromosomal distributions.

In this regard, it is also important that future studies of nuclear organization are performed on tissues or primary cells grown in defined media. In addition to interpretative complications due cell line aneuploidy, Zhu et al. (2013) have recently shown that differences in culture environment, in particular the addition of non-physiological amounts of serum, increase H3K9me3 marks in the PH of cultured cells.

It would also be very helpful to better understand the mechanism of chromosomal movement. We have known for quite some time that chromosome domains diffuse within small constrained volumes (Marshall et al. 1997), but we still do not understand how longer-range repositioning of chromosomal loci occurs (Chuang & Belmont 2007). Although there is strong evidence for nuclear actin and myosin (Mehta et al. 2010, Pederson 2008), it is unclear what the polymerization state or exact function of actin or myosin is in the nucleus. Some evidence suggests they are involved in transcription and chromosome organization (Visa & Percipalle 2010, Ye et al. 2008), although the polymerases themselves may act as motors to spool chromatin during transcription (Papantonis et al. 2010). More high-resolution imaging studies tracking heterochromatic regions and active genetic loci in living cells throughout the cell cycle and during differentiation will be invaluable in understanding the dynamics of chromatin movement and heterochromatin deposition in the nucleus. The development of suitable nontoxic, stable labels for use in live cell tracking studies is crucial for the success of these experiments.

Finally, we need to further discern how heterochromatic elements redistribute among silencing regions and whether these regions are functionally equivalent as repressive compartments. In this context, it will be very important to simultaneously stain all three heterochromatic regions in experiments where gene movement or relocalization is studied, so that proximity with respect to the entire repressive compartment can be more readily evaluated.

Summary Points.

Heterochromatin concentration near the nuclear periphery (PH), the nucleolus (PNH) and in pericentromeric heterochromatin (PCH) foci (chromocenters) is a hallmark of differentiated cells.

The association of both constitutive and facultatively repressed genes with heterochromatic regions can involve specific tethering proteins and this association can change during development and terminal differentiation.

The repressive compartment is re-established after every mitosis, at which time, at least some heterochromatin redistributes within regions of the compartment. Re-formation of the repressive compartment may drive nuclear organization.

Maintenance of the repressive compartment is necessary to protect the genome from illicit recombination between repetitive regions and the resultant loss of genome integrity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thoru Pederson and Rupesh Amin for a thorough reading of the manuscript and insightful comments. We also thank Susan Gasser and members of the Groudine lab for helpful discussions. Work in the Groudine lab is supported by NIH grants R37 DK44746 and RO1 HL65440.

Definitions

- heterochromatic compartment

condensed, DNAse I resistant, mid to late replicating DNA

- euchromatic compartment

decondensed, DNAse I sensitive, early to mid replicating DNA

- pericentromeric heterochromatin (PCH)

DNAse I resistant, highly repetitive, highly condensed DNA regions around centromeres, which in conventional usage includes centromeric sequences

- perinucleolar heterochromatin (PNH)

DNAse I resistant, condensed DNA regions lining the nucleolar periphery

- peripheral heterochromatin (PH)

DNAse I resistant, condensed DNA regions clustered at the nuclear periphery

- nucleolar organizing regions (NOR)

Secondary constrictions near chromosomal ends that harbor rDNA genes

- telocentric chromosomes

Chromosomes with the centromere immediately proximal to the telomere at a terminal end of the chromosome

- acrocentric chromosomes

Chromosomes with the centromere much closer to one telomere than the other

- Nucleolar-Associated Domains (NADs)

DNA sequences that associate endogenously and copurify with nucleoli

- Lamin B1--Associated chromatin Domains (LADs)

DNA sequences that associate with lamin B1

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Contributor Information

Joan C. Ritland Politz, Email: jritland@fhcrc.org.

David Scalzo, Email: scalzod@fhcrc.org.

Mark Groudine, Email: markg@fhcrc.org.

Literature Cited

- Aguirre-Lavin T, Adenot P, Bonnet-Garnier A, Lehmann G, Fleurot R, et al. 3D-FISH analysis of embryonic nuclei in mouse highlights several abrupt changes of nuclear organization during preimplantation development. BMC Dev Biol. 2012;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K, Dehghani H, Rugg-Gunn P, Fussner E, Rossant J, Bazett-Jones DP. Global chromatin architecture reflects pluripotency and lineage commitment in the early mouse embryo. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RP, Fang G, Rozowsky J, Snyder M, Gerstein MB. Annotating non-coding regions of the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:559–71. doi: 10.1038/nrg2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin AA, Hannon GJ. Small RNA silencing pathways in germ and stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:283–90. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Eichler EE. Primate segmental duplications: crucibles of evolution, diversity and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:552–64. doi: 10.1038/nrg1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantignies F, Cavalli G. Cellular memory and dynamic regulation of polycomb group proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantignies F, Roure V, Comet I, Leblanc B, Schuettengruber B, et al. Polycomb-dependent regulatory contacts between distant Hox loci in Drosophila. Cell. 2011;144:214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskara S, Knutson SK, Jiang G, Chandrasekharan MB, Wilson AJ, et al. Hdac3 Is essential for the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:436–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: Establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol Cell. 2012;48:491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolzer A, Kreth G, Solovei I, Koehler D, Saracoglu K, et al. Three-dimensional maps of all chromosomes in human male fibroblast nuclei and prometaphase rosettes. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M, Ranish JA, Kummer NT, Hamilton J, Igarashi K, et al. Dynamic changes in transcription factor complexes during erythroid differentiation revealed by quantitative proteomics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:73–80. doi: 10.1038/nsmb713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brero A, Easwaran HP, Nowak D, Grunewald I, Cremer T, et al. Methyl CpG--binding proteins induce large-scale chromatin reorganization during terminal differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:733–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Ahmed S, Meldi L, Thompson A, Light W, et al. Transcription factor binding to a DNA zip code controls interchromosomal clustering at the nuclear periphery. Dev Cell. 2012;22:1234–46. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockdorff N. Noncoding RNA and polycomb recruitment. RNA. 2013;19:429–42. doi: 10.1261/rna.037598.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KE, Baxter J, Graf D, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG. Dynamic repositioning of genes in the nucleus of lymphocytes preparing for cell division. Mol Cell. 1999;3:207–17. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butin-Israeli V, Adam SA, Goldman AE, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamin functions and disease. Trends Genet. 2012;28:464–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabianca DS, Casa V, Bodega B, Xynos A, Ginelli E, et al. A long ncRNA links copy number variation to a polycomb/trithorax epigenetic switch in FSHD muscular dystrophy. Cell. 2012;149:819–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson M, Corces VG. The ubiquitin ligase dTopors directs the nuclear organization of a chromatin insulator. Mol Cell. 2005;20:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalopin D, Galiana D, Volff JN. Genetic innovation in vertebrates: Gypsy integrase genes and other genes derived from transposable elements. Int J Evol Biol. 2012;2012:724519. doi: 10.1155/2012/724519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra T, Kirschner K, Thuret JY, Pope BD, Ryba T, et al. Independence of repressive histone marks and chromatin compaction during senescent heterochromatic layer formation. Mol Cell. 2012;47:203–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheutin T, Cavalli G. Progressive polycomb assembly on H3K27me3 compartments generates polycomb bodies with developmentally regulated motion. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 2011;44:667–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang CH, Belmont AS. Moving chromatin within the interphase nucleus-controlled transitions? Sem Cell Develop Biol. 2007;18:698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JH, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. A 5′ element of the chicken β-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;74:505–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowney EJ, LeGros MA, Mosley CP, Clowney FG, Markenskoff-Papadimitriou EC, et al. Nuclear aggregation of olfactory receptor genes governs their monogenic expression. Cell. 2012;151:724–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BS, Morales-Alcelay S, Kleiger G, Brown KE, Fisher AG, Smale ST. Targeting of Ikaros to pericentromeric heterochromatin by direct DNA binding. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2146–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.816400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T, Cremer M. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb Persp Biol. 2010;2:a003889. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csink AK, Henikoff S. Genetic modification of heterochromatic association and nuclear organization in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;381:529–31. doi: 10.1038/381529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvačková Z, Mašata M, Stanĕk D, Fidlerová H, Raška I. Chromatin position in human HepG2 cells: although being non-random, significantly changed in daughter cells. J Struct Biol. 2009;165:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasilva C, Hadji H, Ozouf-Costaz C, Nicaud S, Jaillon O, et al. Remarkable compartmentalization of transposable elements and pseudogenes in the heterochromatin of the Tetraodon nigroviridis genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13636–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202284199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit E, de Laat W. A decade of 3C technologies: insIgHtsinsights into nuclear organization. Genes Dev. 2012;26:11–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.179804.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Gajewski A, Korbei B, Gerlich D, Daigle N, et al. LAP2α and BAF transiently localize to telomeres and specific regions on chromatin during nuclear assembly. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6117–28. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]