Abstract

This study evaluated a process for training raters to reliably rate clinicians delivering the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA) in a national dissemination project. The unique A-CRA coding system uses specific behavioral anchors throughout its 73 procedure components. Five randomly-selected raters each rated “passing” and “not passing” examples of the 19 A-CRA procedures. Ninety-four percent of the final ICCs were at least ‘good’ (≥.60) and 66.7% were ‘excellent’ (≥.75), and 95% of the ratings exceeded the 60% or better agreement threshold between raters and the gold standard. Raters can be trained to provide reliable A-CRA feedback for large-scale dissemination projects.

Keywords: Evidence-based treatment, A-CRA, community reinforcement, rater training, coder training, treatment adherence

Considerable research interest in recent years has been focused on the dissemination of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for drug and alcohol abuse (Garner, 2009; Henggeler, Sheidow, Cunningham, Donohue, & Ford, 2008; Miller, Sorenson, Selzer, & Brigham, 2006; Sholomskas et al., 2005). An important component of effective dissemination is the comprehensive training of therapists to assure that they are adhering to the newly learned treatment. Trained raters often are the mechanism for providing therapists with feedback regarding their progress toward mastering a particular therapy and assessing when they have achieved competence in the EBT (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2010). Ensuring that these raters are reliably rating a treatment is an integral component of any project concerned with treatment integrity, and yet relatively little detail has been provided about the process to date.

In fairness, these incomplete descriptions may be due to the intentional emphasis most implementation articles place on the assessment of therapist fidelity, rather than the description or evaluation of rater accuracy. Nonetheless, in order to improve the technology for supporting widespread dissemination of evidence-based treatments in practice settings; namely, to hundreds of clinicians and organizations over large geographic areas, it is important to routinely document the training process for raters and to describe the support components (i.e., rating manuals, ongoing rater supervision). Furthermore, empirical data regarding the reliability of their ratings should be provided, and methods for improving the reliability should be discussed. Such studies seem particularly important once a new treatment integrity coding manual has been developed for a specific EBT that is based on a different coding paradigm than that used by other established coding manuals. This is the case for the coding manual used to evaluate therapists’ progress in implementing the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA; Godley et al., 2001). This rating manual provides specific behavioral anchors for every point (on its 1-5 point scales) for each component of each A-CRA procedure, and thus both the rating criteria and the feedback that is provided to therapists learning the intervention are very detailed (Smith, Lundy, & Gianini, 2007). In this paper we review literature describing coding manuals for other EBTs, describe how the A-CRA coding manual differs, and present findings from a reliability study based on ratings of therapy sessions during a large dissemination project.

Common Components Involved in Training Therapy Raters

The basic training of therapy raters appears quite similar across several types of EBTs. Most rater trainings begin with a didactic seminar and the review of a training manual, and these are followed by the assignment of a series of training tapes to rate. The ratings given by the raters-in-training are then compared to those of “expert raters”. Many studies require that raters achieve a particular level of inter-rater reliability before being allowed to rate therapy sessions independently. These training procedures have been noted in rater training for Motivational Interviewing (MI) and Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET; Madson, Campbell, Barrett, Brondino, & Melchert, 2005; Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2009; Moyers, Martin, Manual, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005; Pierson et al., 2007; Santa Ana et al., 2009). Therapies that are comprised of significantly more procedures and sessions, such as Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT; Hogue, Dauber, Barajas et al., 2008; Hogue, Dauber, Chinchilla et al., 2008) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), also employ similar training protocols for raters (Carroll et al., 2000; Sholomskas et al., 2005).

One critical consideration for any rater training approach is the design and scope of the manual being used to guide raters’ assessment of therapists’ treatment adherence. Arguably the most well known manual is the Yale Adherence and Competence Scale (YACS; Carroll et al., 2000). One of the unique aspects of the YACS is that segments can be used to evaluate therapists’ performance for a variety of evidence-based treatments for alcohol and substance abuse problems, such as CBT, twelve step facilitation, interpersonal therapy, and MI. The revised YACS (YACSII; Nuro et al., 2005) contains several assessment and general support items for use with therapists of all orientations. The CBT section contains 10 items which assess general components of CBT, such as reviewing and assigning homework, exploring drug/alcohol-related triggers, doing role-plays, and teaching coping skills. Each item on the YACS is rated on a 7-point scale on two dimensions: 1) frequency and extensiveness (adherence) and 2) skill level (competence). Raters are told to use a ‘1′ as a starting point for the frequency/extensiveness ratings, and a ‘4′ for the skill level ratings. An overall description of what each item is designed to capture is provided, and explanations of the types of therapist behavior that would be characterized as ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ than the recommended starting points are supplied as well. Examples of therapist dialogue are provided for illustration.

While the YACS is a valuable and popular instrument for assessing treatment integrity, it is a fairly broad manual in that only a total of 10 items are used to evaluate the CBT-specific performance of a therapist during a session. Furthermore, the breakdown that is provided for each of the seven items of the rating scales is of necessity generic, as it is designed to be applicable across all 10 items. For example, the definitions for the skill level ratings for each of the 10 items includes: “2 = Poor. The therapist handled this poorly (e.g., showing clear lack of expertise, understanding, competence, or commitment, inappropriate timing, unclear language); 3 = Acceptable. The therapist handled this in an acceptable, but less than ‘average’ manner” (Nuro et al., 2005, p 9). More specific behavioral anchors are not used, nor are the different procedures broken down into individual components. Such a system potentially limits the precision of the analysis of therapist competence, and consequently the degree of detail that can be included in the feedback to therapists. So for example, the YACs item for “task assignment” (i.e., homework) asks, “To what extent did the therapist develop one or more specific assignments for the patient to engage in between sessions?” (Nuro et al., 2005, p. 93). An average response of ‘4′ would only be interpretable as, “The therapist handled this in a manner characteristic of an ‘average”, ‘good enough’ therapist” (Nuro et al., 2005, p. 93). Raters would not readily be able to provide any details about the specific ways in which the procedure could be improved (e.g., by inquiring carefully about obstacles, by obtaining the client’s input when creating the assignment, by using a measurable behavior), nor would raters be able to provide precise examples of an improved homework assignment.

The Therapist Behavior Rating Scale (Hogue, Rowe, Liddle, & Turner, 1994) is another well-known coding instrument for substance abuse therapy that contains a CBT section. General guidelines are provided for rating extensiveness and competence on a 7-point scale, descriptions of the requirements for each of the 26 items are outlined, and examples of therapists’ dialogue are included. Yet similar to the YACS, the 1-7 scale does not have unique behavioral anchors for each item, nor do the general descriptors vary across items.

In summary, these coding systems rely on relatively few items to characterize their treatment, and use broadly-labeled behavioral anchors that are identical across all items. Although this more general approach may be adequate when working with a small group of clinicians who are involved in clinical trial research and who are closely monitored by a research team, conceivably it may not provide an optimal level of feedback to clinicians from very different training backgrounds who are striving to improve their delivery of an EBT in actual practice and who need specific feedback to do so. With these limitations in mind, a different approach was taken in designing the A-CRA coding manual.

Rating the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach

The impetus for the current study was the widespread dissemination of the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA; Godley et al., 2001) to more than 330 clinicians in over 100 programs which began with a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) grant initiative. These clinicians attended an A-CRA training workshop, and were then required to demonstrate competency in the treatment as part of a certification process. This certification process involved recording actual therapy sessions at their organizations and uploading their therapy session recordings to a secure web-based system for review by raters. The clinicians then received ongoing numeric ratings and narrative reviews of their therapy sessions, as well as bi-monthly supervision calls during the grant period. Clinicians were expected to first demonstrate the competent delivery of nine A-CRA procedures to achieve “Basic Certification” and then eight more to achieve “Full Certification” (Godley, Garner, Smith, Meyers, & Godley, 2011). Based on the last 40 clinicians certified, the process takes an average of 28 weeks and 20 session reviews to reach basic certification, and 46 weeks and 31 session reviews to reach full certification. Due to the number of clinicians in training and the certification process requirements, the number of sessions assigned across multiple raters each week has been as high as 130. Each rater has been expected to provide ratings and narrative feedback to clinicians in seven business days.

A-CRA is an adaptation of the evidence-based Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA); a behavioral therapy originally developed for adults that emphasizes the use of social, recreational, familial, school, or job reinforcers to help individuals in their recovery process (e.g., Azrin, Sisson, Meyers, & Godley, 1982; Hunt & Azrin, 1973; Meyers & Smith, 1995; Smith, Meyers, & Delaney, 1998). A-CRA was found comparable to other evidence-based treatments in a randomized clinical trial with 300 outpatient adolescents, and was significantly more cost-effective than the two other interventions in its study arm (Dennis et al., 2004). Slesnick and colleagues demonstrated A-CRA’s superiority in a randomized clinical trial of 180 street-living youth (Slesnick, Prestopnik, Meyers, & Glassman, 2007). Process research showed that exposure to a variety of A-CRA procedures was a significant mediator of the relationship between treatment retention and outcome (Garner, Godley et al., 2009), and that the intervention was implemented well across gender and racial groups, and was equally effective across racial groups (Godley, Hedges, & Hunter, 2011).

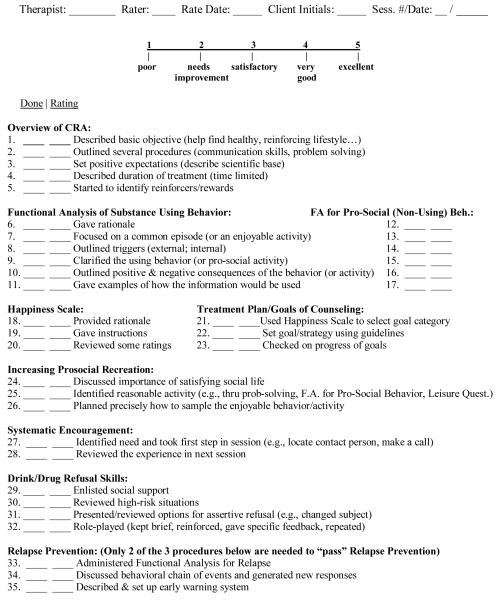

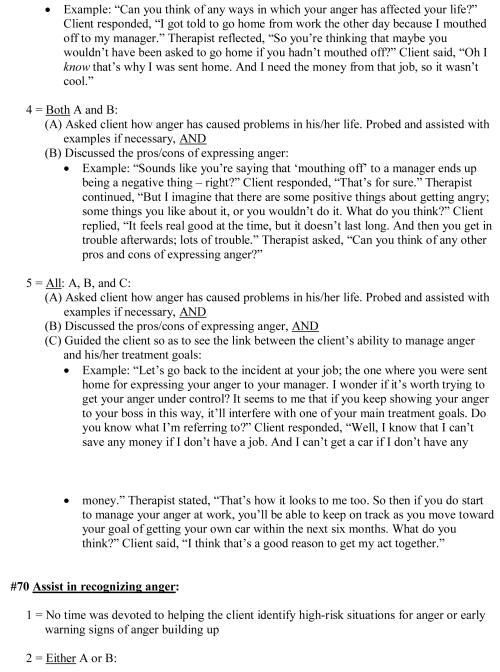

A comprehensive CRA/A-CRA therapist coding manual (Smith et al., 2007) was developed to provide guidelines for raters reviewing digitally recorded A-CRA therapy sessions. This more than 150-page manual contains operational definitions for numeric ratings of each component of 19 A-CRA procedures. In addition to clinicians receiving ratings from this manual for the particular A-CRA procedures demonstrated during a session, they also are rated every session on whether they reviewed and assigned homework. Furthermore, clinicians are given “overall scores” every session related to whether they exhibited the appropriate A-CRA therapeutic style and goals, and introduced procedures at clinically relevant times. Four categories of General Clinical Skills (warmth/understanding, non-judgmental, maintenance of session focus, and appropriate activity level) are rated each session as well. A total of 77 components are listed on the A-CRA checklist (see Figure 1). Raters decide which procedures are appropriate to rate on the basis of what they hear the clinician doing during the session. The numeric ratings range from ‘1′ (poor) to ‘5′ (excellent). A ‘3′ or higher is required to ‘pass’ a component, and all components for a procedure must be at least a ‘3′ for the clinician to ‘pass’ the procedure. Thus, instead of rating one adherence and one competence dimension for a procedure per the YACSII, an A-CRA rater codes between 2-7 components for an A-CRA procedure (once it is identified), and rates the three general areas described above for each session.

Figure 1.

A-CRA Procedures Checklist

Note: The A-CRA Procedures Checklist contains the items that are rated by A-CRA raters; it is the outline for the A-CRA coding manual (Smith, Lundy, & Gianini, 2007).

As an example, the A-CRA Communication Skills procedure has five required components including: (1) discussed why positive communication is important (i.e., gave a rationale for learning the procedure), (2) described the three positive communication elements specific to A-CRA (i.e., offer an understanding statement, accept partial responsibility, offer to help), (3) gave examples of good communication, (4) did a reverse role-play, and (5) did a standard role-play. In order to receive the best rating (‘5′) on just the first component, the rationale, the clinician must (a) explain that positive communication is important by offering the “spirit” of one of the following rationales: positive communication makes it more likely that the client will get what he/she wants, or positive communication is “contagious” such that people are apt to start responding in a positive way to the client; and (b) either provide several reasons for using positive communication that are relevant to the client’s specific situation, or have the client generate one reason (Smith et al., 2007, Section15-page 2).

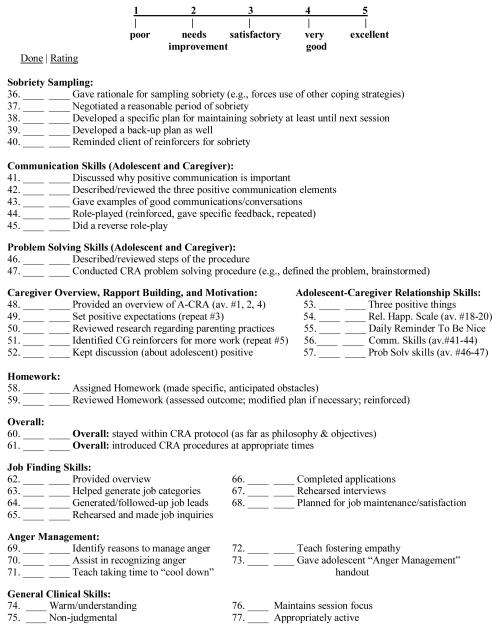

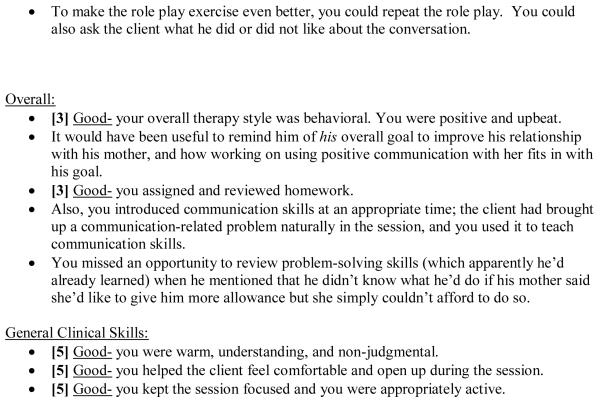

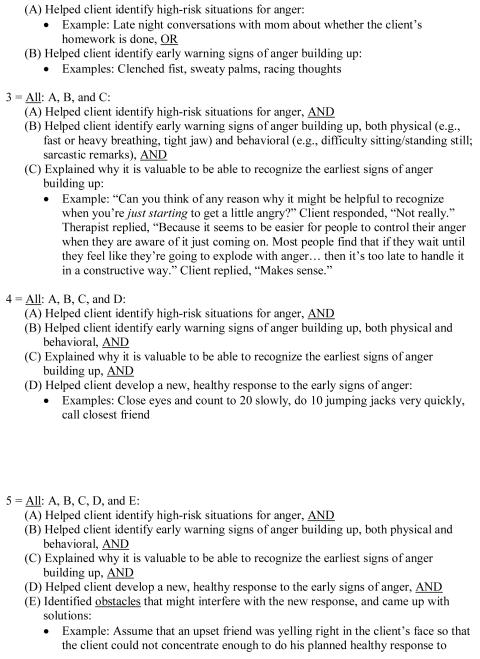

In addition to the numerical feedback, raters offer qualitative comments to explain their ratings, thereby providing clinicians with specific feedback about how to improve their delivery of the intervention. They praise clinicians for treatment procedure components delivered well, and offer concrete suggestions for how they might improve. These suggestions primarily are derived from the coding manual’s stated requirements for the next higher rating for the individual clinician (see Figure 2 for a sample narrative). For example, if the clinician receives a ‘3′ rating, in essence he or she is told what needs to be done to receive a ‘4′ rating. The raters also suggest alternative procedures to use when indicated for a given situation.

Figure 2.

A-CRA Sample Narrative Feedback

Note:_This A-CRA sample narrative shows the type of specific feedback that is offered to therapists about their performance, including suggestions for improving. The numeric ratings assigned to items appear in brackets.

Initially, A-CRA raters were advanced psychology graduate students working with the lead author of the coding manual. As the implementation effort grew, individuals were recruited to serve as A-CRA raters on a contractual basis from recently certified A-CRA clinicians and supervisors at treatment centers who had been trained in the model. This process created a diverse group of raters from across the country who worked with and represented diverse cultural groups (Garner, Barnes, & Godley, 2009).

The primary aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of training raters to provide accurate and reliable assessments of A-CRA treatment fidelity for a large dissemination effort with a comprehensive coding system that was considerably more specific than ones previously described. In order to do this, we assessed the inter-rater reliability of a subset of raters who had been trained to evaluate the ability of community clinicians to deliver A-CRA, and compared the ratings to those of a “gold standard” rating as part of this process. A secondary aim was to determine whether the agreement between raters could be improved after additional telephone supervision and refinement of the A-CRA coding manual.

METHOD

Participants

Potential participants first had to successfully complete their rater training. Training included: (a) attending a 2 ½ day (20 hour) training in the A-CRA model, (b) reviewing general guidelines about the rating process (approximately one hour), (c) rating sample therapy sessions until they matched at least 80% of the ratings of an existing expert rater across a minimum of six A-CRA procedures (i.e., after an average of 10 session reviews; approximately 13.5 hours), and (d) participating in monthly hour-long rater supervision telephone calls that were held to clarify the rating guidelines and to introduce changes to the rating manual when deemed necessary. The second study criterion was that the rater had to regularly rate at least one A-CRA session per month. When this study began, 13 raters met these criteria. Since a prior study evaluating the reliability of a therapist adherence and competence system was based on ratings from five raters (Carroll et al., 2000), we randomly selected five raters from the group of 13 and invited these individuals to participate. All five raters agreed to participate, and each signed the consent form that had been reviewed and approved by the Chestnut Health Systems’ Institutional Review Board.

According to the A-CRA Rater Background form that the five participants completed at the beginning of the study, the raters were an average of 32 years old (range: 25 - 38) and resided in three different states. All five individuals were female, and in terms of ethnicity, four were Caucasian and one was African-American. Four raters had earned a master’s degree, and one had a bachelor’s degree. The participants reported an average of almost six years (71 months) of substance abuse counseling experience (range: 0 - 134 months), and an average of 12 months of clinical experience as an A-CRA clinician (range: 0 - 26 months). Four of the raters were A-CRA clinicians and one was a clinical psychology graduate student. Three of these clinicians had also supervised A-CRA clinicians. The four clinicians had delivered A-CRA to an average of 14.8 clients. The clinical supervisors had supervised an average of 5.3 A-CRA clinicians. Archival data also revealed that before beginning the reliability study, the five individuals had rated an average of 180 therapy sessions each (range: 81-376).

Procedure

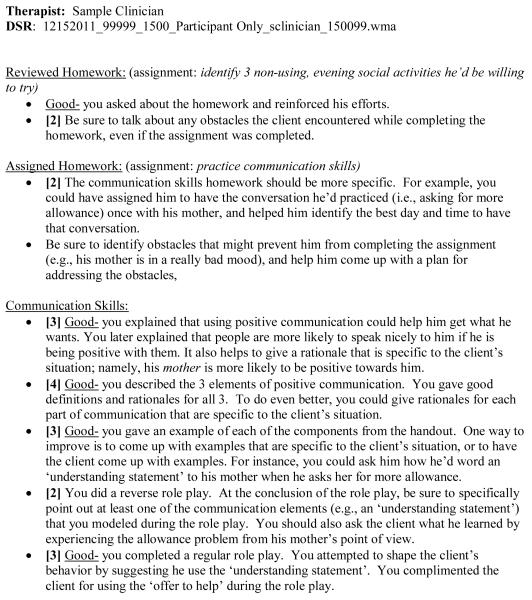

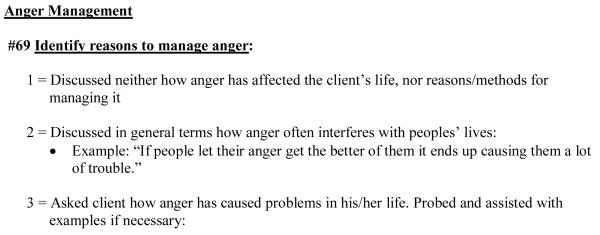

Digital session recordings (DSRs) that contained examples of therapists using the 19 A-CRA procedures were selected from the large set of sessions already rated. Two examples of each procedure were chosen; one in which the therapist was rated as having “passed” the procedure (i.e., received a ‘3′ or higher on each component of the procedure) and one in which the therapist was deemed as having “not passed”. Additionally, DSRs representing a “passed” and a “not passed” version of the Overall A-CRA skills rating (i.e., extent of behavioral style, and the timing of the introduction of the procedures) were selected, as were DSRs containing similar examples for General Clinical Skills. The DSR file names for these 38 sessions were changed in order to de-identify the recording and remove any indication of which A-CRA procedure was represented. The five raters were asked to listen to the 38 DSRs (at a rate of 1-2 per week), rate each DSR using the A-CRA checklist (Figure 1) and coding manual (see sample section, Figure 3), and submit their ratings by e-mail.

Figure 3.

Sample Items from Anger Management Procedure in the A-CRA Coding Manual.

Note: These are two sample items from the Anger Management procedure in the A-CRA coding manual (Smith et al., 2007).

After ratings were completed on the initial 38 DSRs, the analyses described below were conducted to assess inter-rater reliability and the percent agreement with an expert regarding whether the therapist had “passed” or “not passed” the procedure overall. Procedures that had less than acceptable ICCs (i.e., less than .60), or for which there was poor agreement (i.e., less than 60%) regarding whether the procedure was passed or failed, were reviewed during nine hour-long supplemental telephone training calls. All raters for the larger dissemination project (which included the five current study participants) were asked to participate. Reasons for rating discrepancies were solicited and decisions were made regarding how to clarify the scoring language in the rating manual. After this supplemental rater training, changes to the therapist coding manual reflecting clarifications were sent to all raters, who were then required to provide assurance that they had reviewed them and updated their manuals. A completely new DSR with a sample of the treatment procedure that was discussed on the call was then assigned for review. This procedure was followed until all of the procedures needing to be reviewed again were completed.

Analytic Plan

Two methods were used to assess inter-rater reliability. The first used ratings from each of the five randomly selected raters and a co-author of the rating manual (LMG) to calculate an ICC for each of the rated procedures using the two-way random effects model described by Shrout and Fleiss (1979). For the second method, we computed the percentage of agreement between the five randomly selected raters and the criterion rating (the gold standard) provided by this same rating manual co-author.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the inter-rater reliability statistics for the two sets of A-CRA procedure samples: those representing a therapist’s performance that was previously rated as “passed” and those rated as “not passed”. Overall, the majority (71%) of the ICCs were at or above .60, which is considered “good” according to Cicchetti’s (1994) guidelines that suggest ICCs below .40 are poor, ICCs between .40 and .59 are fair, ICCs between .60 and .74 are good, and ICCs between .75 and 1.00 are excellent. In terms of the percent agreement between the five raters and the coding manual co-author’s rating, the average percent agreement across the 38 ratings was 78% (SD = 30%; range 0% - 100%). ICCs could not be computed for the “passed” sample of three procedures (i.e., problem solving skills, job finding skills, and overall) due to the items having a negative average covariance. Furthermore, ICCs could not be calculated for the “passed” sample of two other procedures (i.e., homework and general clinical skills) due to items having zero variance, and for the “not passed” sample of one procedure (i.e., systematic encouragement) because none of the five raters had rated this procedure as having being attempted on the DSR. Of the “passed” procedures for which ICCs could be computed, the average ICC was .66 (SD = .16; range .42 - .97). The average percent agreement for all 19 “passed” procedures was 65% (SD = 35%; range 0% - 100%). Of the “not passed” procedures for which ICCs could be computed, the average ICC was .81 (SD = .14; range .48 to .98). The average percent agreement for all 19 “not passed” procedures was 91% (SD = 15%; range 60% - 100%).

Table 1.

Inter-rater Reliability Statistics for Ratings by Randomly-Selected A-CRA Raters

| “Passed” Samples |

“Not Passed” Samples |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Items | ICC | Raters who rated the procedure as “Passed” |

ICC | Raters who rated the procedure as “Not Passed” |

| Overview of CRA | 5 | .60 | 100% | .68 | 100% |

| Functional Analysis of Substance Use |

6 | .76 | 80% | .76 | 80% |

| Functional Analysis of Prosocial Behavior |

6 | .79 | 20% | .87 | 100% |

| Happiness Scale | 3 | .67 | 20% | .83 | 80% |

| Treatment Plans/Goals of Counseling | 3 | .97 | 100% | .67 | 100% |

| Increasing Prosocial Recreation | 3 | .55 | 80% | .75 | 60% |

| Systematic Encouragement | 2 | .79 | 100% | NC3 | 100% |

| Drink/Drug Refusal Skills | 4 | .84 | 80% | .93 | 100% |

| Relapse Prevention | 3 | .64 | 0% | .96 | 80% |

| Sobriety Sampling | 5 | .45 | 0% | .69 | 100% |

| Communication Skills | 5 | .44 | 60% | .98 | 100% |

| Problem Solving Skills | 2 | NC1 | 80% | .60 | 100% |

| Caregiver Overview and Rapport Building | 5 | .42 | 60% | .94 | 100% |

| Adolescent-Caregiver Relationship Skills | 5 | .66 | 100% | .95 | 100% |

| Homework | 2 | NC2 | 100% | .86 | 60% |

| Job Finding Skills | 7 | NC1 | 40% | .84 | 100% |

| Anger Management | 3 | .64 | 40% | .48 | 100% |

| Overall | 2 | NC1 | 80% | .90 | 100% |

| General Clinical Skills | 4 | NC2 | 100% | .92 | 60% |

| Average | 3.95 | .66 | 65% | .81 | 91% |

Notes. “Passed” Samples = the therapist in the session had been rated previously has having passed the procedure; “Not Passed” Samples = the therapist in the session had been rated previously as not having passed the procedure; ICC = Intraclass correlation coefficient.

NC1 = ICC could not be computed due to items having a negative average covariance.

NC2 = ICC could not be computed due to items having zero variance.

NC3 = ICC not computed because none of the randomly selected raters rated this procedure as having been attempted.

Table 2 presents results of ICCs and rater agreement after the nine supplemental training calls were conducted. The majority (60%) of the ICCs were now considered excellent (i.e., between .75 and 1.00) for the re-rated A-CRA procedures. Additionally, the ICC for the Functional Analysis of Prosocial Behavior was good (.66), the ICC for Sobriety Sampling was fair (.52), and the ICC for the Happiness Scale could not be computed due to items having zero variance. It should be noted, however, that the zero variance resulted from raters primarily giving consistent ratings of 4 (on the 1-5 scale). Thus, although an ICC was unable to be computed, there was good-to-excellent agreement. In terms of the percent agreement between the five raters and the gold standard rating, the average percent agreement across the ratings was 69% (SD = 28%; range 20% - 100%). Final results indicated that 94% of the 38 ICCs that could be calculated were at least in the ‘good’ range (≥ .60), and 66.7% actually reached the ‘excellent’ range (≥ .75). Furthermore, 95% of the 38 ratings exceeded the 60% or better agreement threshold between raters and the gold standard.

Table 2.

Comparison of Initial and Post-Supplemental Rater Training Telephone Calls

| ICC |

Percent Agreement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Supplemental | Post-Supplemental | |||

| Procedure | Initial | Training | Initial | Training |

| Functional Analysis of Prosocial Behavior+ |

.79 | .66 | 20% | 60% |

| Happiness Scale+ | .67 | NC2 | 20% | 100% |

| Increasing Prosocial Recreation+ |

.55 | .88 | 80% | 100% |

| Relapse Prevention+ | .64 | .90 | 0% | 20% |

| Sobriety Sampling+ | .45 | .52 | 0% | 40% |

| Communication Skills+ | .44 | .88 | 60% | 60% |

| Caregiver Overview and Rapport Building+ |

.42 | .23 | 60% | 100% |

| Job Finding Skills+ | NC1 | .90 | 40% | 60% |

| Anger Management+ | .64 | .81 | 40% | 80% |

| Anger Management− | .48 | .95 | 100% | 100% |

Notes: + indicates the example was of a therapist who had been rated previously as having passed the procedure; − indicates the example was of a therapist who had been rated previously as not having passed the procedure; ICC = Intraclass correlation coefficient.

NC1 = ICC could not be computed due to items having a negative average covariance.

NC2 = ICC could not be computed due to items having zero variance.

DISCUSSION

When disseminating EBTs to community-based behavioral healthcare organizations, it is necessary to include a mechanism to determine whether therapists trained in an EBT can, in fact, administer the therapy in a competent manner. Randomized clinical trials have determined that the best methods for improving adherence for an EBT are approaches that include feedback or supervision based on reviews of the therapist’s performance within therapy sessions (Martino et al., 2010; Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005). The manner in which the raters who give this feedback are trained and evaluated has not routinely been reported in a comprehensive manner in the literature, and the intricacies of the coding process have never been reported for raters of A-CRA. Considering the critical role played by raters, as well as the substantial effort and cost involved in utilizing them (Langer, McLeod, & Weisz, 2011), a careful investigation of the reliability of A-CRA raters’ work while using a newly developed coding manual appeared merited. Furthermore, given that an ongoing large-scale dissemination effort for A-CRA is requiring an entire network of treatment raters in order to provide clinicians with treatment adherence and competence feedback in a timely fashion (Godley et al., 2011), an examination of the reliability of A-CRA rating seemed warranted.

The current study determined that a subset of raters randomly selected from a pool of trained A-CRA raters was able to reliably code community therapists’ sessions using the A-CRA coding manual (Smith et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, additional discussion and clarification of rating instructions via a series of supplemental telephone conference calls was generally helpful in improving the agreement among the raters and with the “expert” (gold standard) rater. Our rater reliabilities were similar to those found in other studies assessing treatment fidelity (Moyers et al., 2005; Santa Ana et al., 2009), albeit they were somewhat lower than those found in two studies (Carroll et al., 2000; Pierson et al., 2007) and higher than the ratings in several others (Hogue, Dauber, Barajas, et al., 2008; Hogue, Dauber, Chinchilla, et al., 2008; Madson et al., 2005; Martino et al., 2009). Conceivably the current study’s lower rating reliability when compared to a treatment with many fewer sessions and/or procedures reflects a more complex system for rating A-CRA. Nonetheless, ongoing refinement of the A-CRA rating system and the rater training process is required to continually improve the accuracy and reliability of ratings.

The raters in the current study were trained as part of a federal contract designed to train numerous raters who were needed to ensure a successful large-scale simultaneous dissemination of A-CRA across 100 sites. Once developed, the rater training process was adapted to promote sustainability at the ‘real-world’ practice sites that were funded for implementation of the EBP by teaching the supervisors how to incorporate ratings as part of ongoing clinical supervision. One requirement for supervision certification was to review and rate at least one clinician’s session weekly. This process ensured that clinical supervisors developed the knowledge to critically evaluate A-CRA procedures delivered by their clinicians and provide feedback to help them improve EBP delivery. Supervisors were required to match the expert raters at 80% or better for at least six A-CRA sessions, and they received feedback on each rating. During this process, supervisors were provided and learned to use the CRA/A-CRA rating manual. Thus, as part of regular clinical supervision training these supervisors learned the skills to review and rate recorded therapy sessions for their clinicians, and to give feedback either in individual or group supervision sessions.

Future research in the rater coding process ideally should proceed in multiple directions based on one’s desired goals. Some researchers have identified the need for studies to use standardized measures of adherence/competence that permit comparisons across studies that aim to evaluate the effectiveness of similar treatments (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Carroll et al., 2000). Although this would appear to address the issue of comparability of findings across studies, it would seem to sacrifice the level of specificity required for treatments that contain unique components. In terms of A-CRA, one could argue that certain items within the YACSII coding system are applicable to a behavioral treatment like A-CRA, such as the homework items (previous assignment, task assignment), and the role-play. Also, there are three YACSII items that cover components of the A-CRA Functional Analysis (past high risk situations, future high risk situations, exploration of cravings/triggers/urges for drugs of choice). However, not only does the A-CRA coding system incorporate these three items into its own rating module for Functional Analysis, but it offers item-specific behavioral definitions of each 1-5 rating for them as well. So while the A-CRA coding system is not generic and thus does not lend itself readily to adoption across a variety of treatments, this characteristic could be considered a strength of the coding system as far as the wealth of information it is set up to provide for therapists-in-training.

Still another line of research is to determine the specific degree to which treatment integrity can, in fact, be monitored by supervisors (and therapists) as opposed to expert raters (Sheidow, Donohue, Hill, Henggeler, & Ford, 2008), and to further clarify the contribution offered by client (youth and caregiver) reports of session content (Henggeler et al., 2008). This line of research will help identify more economical means for community agencies to assess treatment fidelity than by using expert raters, and conceivably could be a cost-effective alternative for researchers when their goal simply is to assess fidelity after therapists have already demonstrated competence in a therapeutic approach. As noted above, for the most part real-world practice supervisors eventually should be able to serve this function, but they first need to be adequately trained to be raters themselves by participating in a certification process similar to the training of expert raters already outlined (Godley, Garner et al., 2011). In terms of therapists rating themselves, the precise goal of such a rating approach would need to be considered, since it clearly would be limited in comparison to an expert rating system that includes specific comments about a therapist’s strengths and weaknesses, and which articulates the changes a therapist must make in order to improve.

One of the strengths of this study is that it took place in the context of a large-scale dissemination effort during which raters provided fidelity ratings for clinicians located in community-based organizations. Thus, our results are an accurate reflection of how raters assess fidelity in a “real world” setting. Additionally, since the raters for this study were randomly selected from amongst all raters, as opposed to being the five best raters, our study represents an evaluation of our rater training process. Furthermore, we examined rating reliability with two types of therapy samples for each procedure: ones in which the therapist had previously been rated as having passed the procedure, and ones in which the therapist had not passed. This step was undertaken because we realized it might have been easier or more difficult to rate ‘good’ sessions versus ‘poor’ sessions. We calculated reliability in two ways: ICC’s and overall percent agreement regarding whether the therapist conducting the procedure had “passed” or not. The percent agreement offered a clinically relevant test, given that therapists in this larger dissemination effort were concerned with whether or not they had “passed” a procedure as they progressed toward certification. As expected, we were able to demonstrate that we could improve the reliability of session ratings following supplemental training via conference calls.

One limitation of the current study is that when adequate rater reliability was not demonstrated for a procedure upon its initial review, limited resources only allowed us to offer one supplemental telephone training call and one additional session rating attempt to improve reliability for that procedure. Regrettably this did not appear to be sufficient for some procedures, as evidenced by the decrease in ICC for both the Functional Analysis of Prosocial Behavior and the Caregiver Overview and Rapport Building procedures. Importantly, although lower than the initial rating, the second ICC for the Functional Analysis of Prosocial Behavior was still considered good. Additionally, the second ICC for the Caregiver Overview and Rapport Building remained in the poor range. Thus, as others have found, it seems important to have ongoing and regular booster sessions with raters, which allows discussion of rating issues that have arisen (Miller et al., 2004). It also appears important to institute other methods of monitoring raters’ attention to detail, especially when there are changes made to a rating system periodically. As an example, we have introduced online multiple-choice ‘exams’ to test raters’ knowledge of rating manual changes. We also have allowed therapists to request ‘re-reviews’ for situations in which they believe their review was unfair. This serves two purposes. First, the implementation team can track the number and results of re-reviews by rater so that additional instruction can be provided. Second, the therapist is more likely to feel as if the team is attempting to create a collaborative rather than a ‘top down’ approach to the training process.

Another limitation of the current study is that we only rated one session of each sample (e.g., Happiness Scale: “Passed” by a therapist and Happiness Scale: “Not Passed” by a therapist). A more accurate estimate of the general consistency of the raters may have been determined if the raters had assessed several sessions of each sample type. Still, it should be noted that with five raters and a manual co-author initially rating two samples of each type of session, and with the additional ratings added for the supplemental training, a total of 288 different sets of ratings were part of the analyses reported in this study. Lastly, it is unclear to what extent these findings might generalize to quality assurance efforts for other EBTs, given that A-CRA raters must assess clearly delineated components of each of the procedures, whereas other systems tend to evaluate the more global skills related to an intervention (e.g., CBT, MI; Carroll et al., 2000; Gibbons et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2009; Moyers et al., 2005; Pierson et al., 2007; Santa Ana et al., 2009).

Overall, the rater training system implemented as part of the current study appears to be a reliable mechanism by which clinicians can be trained and monitored to implement A-CRA therapy with high levels of treatment fidelity. There is already empirical support demonstrating that the more A-CRA procedures a therapist reports attempting, the better the client outcomes (Garner et al., 2009). The next step is to assess the validity of the rating process. Such a study is challenging because, as noted, the ultimate goal of the training process is that all ‘certified’ therapists would produce essentially similar client outcomes. Nonetheless, it can be expected that therapists will start at different levels of competence, and these differences can have an effect on client outcomes. Thus, in order to assess whether better average ratings predict better client outcomes, we plan to examine whether or not the level of therapists’ competence during their certification process predicts client outcome in a linear fashion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) contract 270-07-0191, and by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; R01-AA017625). The opinions are those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of the federal government. The authors thank the raters who participated in the study, the trainees whose clinical work was rated, and Christin Bair, Brandi Barnes, Jutta Butler, Mark D. Godley, Courtney Hupp, Stephanie Merkle, Robert J. Meyers, Randolph Muck, Laura Reichel, and Kelli Wright for their help and support on this project.

Contributor Information

Jane Ellen Smith, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

Loren M. Gianini, Yale University School of Medicine, Psychiatry, New Haven, CT

Bryan R. Garner, Chestnut Health Systems, Normal, IL

Karen L. Malek, Chestnut Health Systems, Normal, IL

Susan H. Godley, Chestnut Health Systems, Normal, IL

REFERENCES

- Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M. Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1982;13:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90050-7. doi:10.1016/0005-7916(82)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry RL, Nuro KF, Frankforter TL, Ball SA, Fenton L, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Funk RR. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR. Research on the diffusion of evidence-based treatments within substance abuse treatment: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:376–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR, Barnes B, Godley SH. Monitoring fidelity in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA): The training process for A-CRA raters. Journal of Behavior Analysis in Health, Sports, Fitness, and Medicine. 2009;2:43–54. doi: 10.1037/h0100373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR, Godley SH, Funk RR, Dennis ML, Smith JE, Godley MD. Exposure to Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA) treatment procedures as a mediator of the relationship between adolescent substance abuse treatment retention and outcome. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.007. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons CJ, Nich C, Steinberg K, Roffman RA, Corvino J, Babor TF, Carroll KM. Treatment process, alliance, and outcome in brief versus extended treatments for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 2010;105:1799–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03047.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Garner BR, Smith JE, Meyers RJ, Godley MD. A large-scale dissemination and implementation model for evidence-based treatment and continuing care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18:67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01236.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Hedges K, Hunter B. Gender and racial differences in treatment process and outcome among participants in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:143–154. doi: 10.1037/a0022179. doi:10.1037/a0022179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Meyers RJ, Smith JE, Godley MD, Titus JC, Karvinen T, Kelberg P. The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) for adolescent cannabis users, Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Manual Series, Volume 4 (DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 01-3489) Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ, Cunningham PB, Donohue BC, Ford JD. Promoting the implementation of an evidence-based intervention for adolescent marijuana abuse in community settings: Testing the use of intensive quality assurance. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:682–689. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Barajas P, Fried A, Henderson C, Liddle H. Treatment adherence, competence, and outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(4):544–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.544. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Chinchilla P, Fried A, Henderson C, Inclan J, Liddle HA. Assessing fidelity in individual and family therapy for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.002. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Rowe C, Liddle H, Turner R. Scoring manual for the Therapist Behavior Rating Scale (TBRS) Center for Research on Adolescent Drug Abuse, Temple University; Philadelphia, PA: 1994. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GM, Azrin NH. A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1973;11:91–104. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90072-7. doi:10.1016/0005-7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer D, McLeod B, Weisz J. Do treatment manuals undermine youth-therapist alliance in community clinical practice? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:427–432. doi: 10.1037/a0023821. doi:10.1037/a0023821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson M, Campbell T, Barrett D, Brondino M, Melchert T. Development of the motivational interviewing supervision and training scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:303–310. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.303. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Frankforter T, Carroll K. Correspondence of motivational enhancement treatment integrity ratings among therapists, supervisors, and observers. Psychotherapy Research. 2009;19:181–193. doi: 10.1080/10503300802688460. doi:10.1080/10503300802688460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. Teaching community program clinicians motivational interviewing using expert and train-the-trainer strategies. Addiction. 2010;106:428–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03135.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Smith JE. Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The Community Reinforcement Approach. Guilford Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorenson J, Selzer J, Brigham G. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T, Martin T, Manual J, Hendrickson S, Miller W. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuro KF, Maccarelli L, Ball SA, Martino S, Baker SM, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. Yale Adherence and Competence Scale (YACSII) guidelines. 2nd edition Yale University Psychotherapy Development Center; West Haven, CT: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson H, Hayes S, Gifford E, Roget N, Padilla M, Bissett R, Fisher G. An examination of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana E, Carroll K, Anez L, Paris M, Jr., Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S. Evaluating motivational enhancement therapy adherence and competence among Spanish-speaking therapists. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, Donohue BC, Hill HH, Henggeler SW, Ford JD. Development of an audiotape review system for supporting adherence to an evidence-based treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:553–560. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.5.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas D, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville B, Ball S, Nuro K, Carroll K. We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL, Meyers RJ, Glassman M. Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.010. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Lundy SL, Gianini L. Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) and Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA) therapist coding manual. Lighthouse Institute; Bloomington, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Meyers RJ, Delaney HD. The Community Reinforcement Approach with homeless alcohol-dependent individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:541–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.541. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb C, DeRubeis R, Amsterdam J, Shelten R, Hollon S, Dimidjian S. Two aspects of the therapeutic alliance: Differential relations with depressive symptom change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:279–283. doi: 10.1037/a0023252. doi:10.1037/a0023252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]