Abstract

Heterotrimeric G proteins are an important class of eukaryotic signaling molecules that have been identified as central elements in the pheromone response pathways of many fungi. In the fungal pathogen Candida albicans, the STE18 gene (ORF19.6551.1) encodes a potential γ subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein; this protein contains the C-terminal CAAX box characteristic of γ subunits and has sequence similarity to γ subunits implicated in the mating pathways of a variety of fungi. Disruption of this gene was shown to cause sterility of MTLa mating cells and to block pheromone-induced gene expression and shmoo formation; deletion of just the CAAX box residues is sufficient to inactivate Ste18 function in the mating process. Intriguingly, ectopic expression behind the strong ACT1 promoter of either the Gα or the Gβ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein is able to suppress the mating defect caused by deletion of the Gγ subunit and restore both pheromone-induced gene expression and morphology changes.

INTRODUCTION

Heterotrimeric G protein-mediated signal transduction is ubiquitous and regulates many critical processes in eukaryotic cells (for a review, see reference 1). The general paradigm for the function of these heterotrimeric G proteins is that the Gα and Gβγ elements are activated through dissociation or conformational changes triggered by GTP binding to the Gα subunit in response to ligand binding to a G protein-linked 7-transmembrane-spanning receptor protein (2). The signal is ultimately inactivated by reassociation after GTP hydrolysis to GDP (3), often through the aid of a regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protein that serves as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for the process (4).

The involvement of a heterotrimeric G protein in a fungal mating signaling pathway was first noted for the baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5–7); for a review, see reference 8. Detailed genetic analysis in S. cerevisiae suggested that the functioning of this module fit well to the paradigm established through biochemical analysis of mammalian G protein systems, in that the α and βγ subunits played distinct (and opposing) roles in the signaling process. Although many of the well-studied mammalian pathways used the α subunit as the effector activator, the yeast system was an initially identified member of the now-extensive class of pathways in which the βγ subunit served to activate the downstream components of the pathway, in this case by directing the membrane association and activation of members of an Ste5p-scaffolded mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase module (9, 10). The S. cerevisiae Gα (ScGα) subunit serves a role primarily in downregulating the pheromone signaling pathway (11), while the activated MAP kinase triggers the activity of the transcription factor Ste12p, which induces the transcription of pheromone-responsive genes (12), and also phosphorylates and stabilizes Far1p to initiate cell cycle arrest (13).

Recently the number of fungal mating pathways known to involve a heterotrimeric G protein has increased. The fungal pathogen Candida albicans has been demonstrated to show mating between MTLa and MTLα strains in vivo (14) and in vitro (15) and to have a pheromone response pathway similar to that of S. cerevisiae (16). As is the case in S. cerevisiae, C. albicans also has a unique Gα subunit implicated in regulation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling, designated Gpa2 (17), while the classic heterotrimeric G protein is implicated in the mating process. However, in the C. albicans system, loss of either the CaGα or CaGβ of the mating pathway heterotrimeric G protein (encoded by CAG1 and STE4, respectively) results in full sterility (18), unlike in S. cerevisiae, where loss of the Gα subunit leads to constitutive signaling. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the pheromone signaling pathway is regulated only by the SpGα1 subunit; it appears that neither the SpGβ subunit nor the SpGγ subunit is involved in this process (19). In Cryptococcus neoformans, there are three Gα subunits, one Gβ subunit, and two Gγ subunits; CnGα2 upregulates the pheromone response pathway, while CnGα3 inhibits the signaling pathway (20). In Kluyveromyces lactis, the signal transduction pathway that mediates mating is positively regulated by both the KlGα (21) and KlGβ (22) subunits of the heterotrimeric G protein, while loss of the KlGγ subunit produces only a minor mating defect (23). Thus, while a heterotrimeric G protein is a common element in many fungal mating response pathways, the specific roles of the subunits appear to differ significantly from one system to another.

In the present study, we have focused on the function of the heterotrimeric G protein Gγ subunit of the fungal pathogen C. albicans. Mating in C. albicans is a somewhat more complex process than that in S. cerevisiae or K. lactis, in that the typical C. albicans strain is a nonmating a/α diploid. Mating type homozygosis must occur prior to mating: a low percentage of clinical isolates have become homozygous at the MTL locus, forming either a/a or α/α cells (24), and this homozygosis can be selected for in the lab by growth of a/α strains on sorbose medium (15). However, homozygosis of the mating type locus MTL is not sufficient for mating in C. albicans; it simply eliminates the a1-α2 repressor that blocks potential activation of the mating-competent opaque state (25). In the absence of the a1-α2 repressor, cells can establish this mating-competent epigenetic state, which is characterized by high-level expression of the WOR1 gene and by unique cell and colony morphologies (26). However, once the mating-competent opaque state is achieved, C. albicans mating proceeds in a manner similar to that of S. cerevisiae and K. lactis.

In S. cerevisiae, Gγ is critical for normal mating and loss of Gγ blocks mating in strains with pathways activated either normally, by overproduction of Ste4p (Gβ) (27), or by deletion of GPA1(Gα) (7). In contrast, in K. lactis cells, the Gγ subunit is essentially dispensable for mating, as loss of Gγ compromises mating only moderately and then only when both partners lack the subunit (23). As the K. lactis and S. cerevisiae lineages diverged from the C. albicans lineage before the split between K. lactis and S. cerevisiae, it is of interest to establish what role the Gγ of the pathogen plays in mating signal transduction. We found that, as in S. cerevisiae, the C. albicans Gγ is required for mating. However, in contrast to the situation in S. cerevisiae, this requirement can be eliminated by ectopic expression of either the Gα or Gβ subunit of the G protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The C. albicans strains and oligonucleotides used in this work are listed in Tables 1 and 2. For general growth and maintenance of the strains in the white phase, the cells were cultured in fresh YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 2% dextrose, 2% agar for solid medium, pH 6.5) at 30°C. Strains were switched from the white phase to the opaque phase in two rounds of screening on plates with synthetic N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 0.15% amino acid mix with uridine at 100 μg/ml, 2% GlcNAc, and 2% agar for solid medium) (28) and synthetic dextrose (SD) medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 0.15% amino acid mix with uridine at 100 μg/ml, 2% dextrose, and 2% agar for solid medium). Phloxine B was added to nutrient agar for opaque colony staining (18). Cultures in SD medium at room temperature were used to maintain the cells in the opaque phase, and the typical oblong cell morphology phenotype of the cells in the opaque phase was confirmed by microscopy.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Mating type | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3294 | CNC43 | a/a | his1/his1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | P. T. Magee |

| 3315 | CNC43 | α/α | trp1/trp1 lys2/lys2 | P. T. Magee |

| LH001 | 3294 | a/a | STE18/ste18::HIS1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH002 | LH001 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH003 | LH002 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::HIS1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH006 | LH003 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::HIS1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 (CIP10) | This study |

| LH011 | 3294 | a/a | STE18-carboxy-terminal MTD/ste18-carboxy-terminal MTD::HIS1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH012 | LH011 | a/a | ste18-carboxy-terminal MTD::HIS1/ste18-carboxy-terminal MTD::URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH004 | LH003 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::HIS1 RPS1/rps1::STE18-URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH005 | LH003 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::HIS1 RPS1/rps1::STE18ΔC-URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH021 | LH003 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::HIS1 RPS1/rps1::act-STE4-URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

| LH022 | LH003 | a/a | ste18::HIS1/ste18::HIS1 RPS1/rps1::act-CAG1-URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | This study |

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Name | Description | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|---|

| STE18-TB-F | STE18 deletion PCR cassette forward primer | TTTTGATGTAAAAATTAACATGAAAGATTGTGTTTCAGAATTTTCTCCACCTACAACAACAACGACGACAATAACTAGATtatagggcgaattggagctc |

| STE18-TB-R | STE18 and STE18ΔC deletion PCR cassette reverse primer | ATGTATATATATATATATAAATACATATGTGTGTGATTTCATTCTTGTGGGTTGATTAATTGGAGAACTATTTCTGTCGTgacggtatcgataagcttga |

| STE18ΔC-TB-F | STE18ΔC deletion PCR cassette forward primer | TGGAGTTTACCTCCAGATCAGAATAGATTTGCCAAATATAAACAGTTGAGAAATGCACGCAATTCATCTCAAGCTACAGTTtatagggcgaattggagctc |

| STE18-F-ex | STE18 forward external primer | GATTATTACAAGGTGCATTTGC |

| STE18-R-ex | STE18 reverse external primer | AACATTGAAAGCTCAATTAGGC |

| STE18-F-in | STE18 forward internal primer | GAATTCAAGAGTTGACTAATCG |

| HIS1-F | HIS1 forward primer | TTTAGTCAATCATTTACCAGACCG |

| HIS1-R | HIS1 reverse primer | TCTATGGCCTTTAACCCAGCTG |

| URA3-F | URA3 forward primer | TTGAAGGATTAAAACAGGGAGC |

| URA3-R | URA3 forward primer | ATACCTTTTACCTTCAATATCTGG |

| STE18-SalI | STE18 and STE18ΔC forward primer for reintegration | CTGATGGTCGACGATTATTACAAGGTGCATTTGC |

| STE18-HindIII | STE18 reverse primer for reintegration | CCCAAGCTTGGGAACATTGAAAGCTCAATTAGGC |

| STE18ΔC-HindIII | STE18ΔC reverse primer for reintegration | CCCAAGCTTGGGTTAAACTGTAGCTTGAGATGAATTGCG |

| RPS1-R-in | RPS1 reverse internal primer | TTTCTGGTGAATGGGTCAACGAC |

| ACT-F | Actin promoter internal primer | TTTTCTAATTTTCACTCCTGG |

| CAG1-F-in | CAG1 forward internal primer | ATTGAACAAAGTTTACAATTGCGTC |

| CAG1-R-in | CAG1 reverse internal primer | TCATTAGTATCGTCTGGTTTGCC |

| STE4-F-in | STE4 forward internal primer | ACTATACAACACCTTGCGAGGA |

| STE4-R-in | STE4 reverse internal primer | CAGTTGCCAAAGCTACACCATC |

Lowercase letters represent sequences used to prime the synthesis of the selectable marker, and boldface letters indicate introduced restriction enzyme cleavage sites.

Disruption of the STE18 gene and deletion of the C terminus of the STE18 gene.

The C. albicans sequence (assembly 19) from the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/) was used as the reference for the genomic sequence. The two alleles of the STE18 gene (ORF19.6551.1) were deleted from the MTLa strain 3294, obtained initially from P. T. Magee (Table 1). All the disruptions were done using a two-step PCR method as described previously (29), with the replacement of the first allele with HIS1 and of the second allele with URA3. Oligonucleotides STE18-TB-F and STE18-TB-R were used to prepare the cassettes for the deletion of the STE18 gene. The strain produced by replacing the first copy of the STE18 gene by HIS1 in the MTLa strain 3294 was named LH001. The correct insertion of the HIS1 cassette at the STE18 locus was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA from strain LH001 with oligonucleotides STE18-F-ex plus HIS1-R, STE18-R-ex plus HIS1-F, and STE18-F-ex plus STE18-R-ex. Oligonucleotides STE18-F-ex and STE18-R-ex flank and are external to the recombination sites of the PCR cassettes. Oligonucleotides HIS1-F and HIS1-R are internal relative to the HIS1 gene of the PCR cassettes. The second copy of the STE18 gene was deleted from strain LH001 by replacement with the URA3 cassette to generate the ste18 null strain LH002. The correct insertion of the URA3 cassette at the STE18 locus was confirmed by PCR with oligonucleotides STE18-F-ex plus URA3-R and STE18-R-ex plus URA3-F. The carboxyl terminus of the STE18 gene was deleted using a similar strategy. Oligonucleotides STE18ΔC-TB-F and STE18-TB-R were used to prepare the PCR cassettes. The strain produced by deleting one allele from the parent strain 3294 was named LH011. The correct insertion of the HIS1 cassette at the carboxyl terminus of the STE18 gene was confirmed by PCR with oligonucleotides STE18-F-in plus HIS1-R and STE18-R-ex plus HIS1-F. Strain LH011 was then transformed with the URA3 cassette to remove the CAAX box of the second allele to STE18 gene to generate the carboxyl-terminal CAAX box-deleted strain LH012. The correct insertion site of the URA3 cassette was confirmed by PCR with oligonucleotides STE18-F-in plus STE18-R-ex.

Reintegration.

A copy of the wild-type gene for complementation experiments was reintegrated at the RPS1 locus in the ste18Δ strain as described previously (18). The recipient strain LH002 was treated with 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) to recover the URA3 marker. A resulting uridine-negative strain was named LH003. For the STE18 gene, a 1,320-bp DNA fragment from genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides STE18-SalI and STE18-HindIII. Oligonucleotide STE18-SalI contains an exogenous SalI restriction site, absent in the STE18 gene sequence, near its 5′ end, and STE18-HindIII contains an exogenous HindIII restriction site in the 3′-end noncoding sequence of the STE18 gene. The PCR fragment was digested with SalI and HindIII, the resulting 1.3-kb fragment was ligated with vector CIp10 (30) also cut with SalI and HindIII, and Escherichia coli strain DH5α was transformed with the construct. The integrity of the clone with respect to the STE18 wild-type sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The selected clone for the wild-type STE18 gene was named plasmid pCIP-STE18 and was digested with the enzyme StuI for transformation of strain LH003. The new STE18 strain was named LH004. A similar strategy and protocol were used for the reintegration of the STE18ΔC gene. An 820-bp fragment was amplified with oligonucleotides STE18-SalI and STE18ΔC-HindIII. Oligonucleotide STE18ΔC-HindIII was designed with an exogenous HindIII restriction site, absent in the STE18 gene sequence, and is positioned in the 3′ end of the STE18 gene open reading frame (ORF), which did not include the last 21 bp (GGTTGTTGTACAATTGTTTAA). This PCR fragment was digested with SalI and HindIII, and the 820-bp fragment was ligated to the CIp10 vector cleaved with the same two enzymes. The integrity of the clone was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the selected clone with the STE18ΔC gene sequence was named plasmid pCIP-STE18ΔC. This plasmid was digested with StuI, and strain LH003 was transformed with the construct. This new STE18 strain was named LH005. The integration of pCIP-STE18 and pCIP-STE18ΔC at the correct site in the RPS1 locus was confirmed by PCR. A strain carrying an insertion of the original vector CIP10 with no insert was also constructed and designated LH006.

Ectopic expression of either the STE4 gene or the CAG1 gene in ste18 null mutant strains.

To overexpress the STE4 gene or the CAG1 gene in ste18Δ strains, we used plasmids pl390 (wild-type STE4 gene under control of the ACT1 promoter) or pl391 (wild-type CAG1 gene under control of the ACT1 promoter) (18) for transformation. Plasmids pl390 and pl391 were digested with StuI and then transformed into ste18Δ strains. The ste18Δ strain transformed with plasmid pl390 was named LH021, while that with plasmid pl391 was named LH022. The correct integration of the plasmids was confirmed by PCR.

Microarray analysis.

The transcriptional response to pheromone treatment was measured in the wild-type strain, in a strain (LH003) deleted for STE18, and in STE18-deleted strains overexpressing either the STE4 gene (LH021) or the CAG1 gene (LH022). Standard protocols were performed as follows: we collected cells from SD-complete cultures in log phase with and without pheromone induction, and we used the hot-phenol method for RNA extraction (18), the polyA Spin mRNA isolation kit for mRNA isolation (18), and reverse transcription for cDNA production, followed by indirect chemical labeling for dye addition. Arrays obtained from NRC-BRI (18) were hybridized in a hybridization chamber at 42°C for overnight incubation and then washed and scanned. The scanning was done using a GenePix4000B microarray scanner, and the images were analyzed in GenePix Pro 4.1; the output data were processed with Microsoft Excel 2013 and MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV).

Mating assays.

Patch mating experiments, using auxotrophic marker complementation with strain 3315 as the MTLα tester strain, were done as described previously (31). Briefly, all the assayed strains were maintained in the opaque phase at room temperature. Experimental and tester strains were streaked as straight lines on separate YPD plates. After 24 h of incubation at room temperature, the two sets of streaks were crossed onto a single fresh YPD plate and incubated for 24 h at room temperature. After 24 h of incubation, cells were replicated to dropout plates containing SD medium minus five amino acids (uridine, histidine, arginine, tryptophan, and lysine) for selection of mating products and to YPD plates as a control. All the plates were incubated at room temperature for 5 days prior to scoring.

Quantitative assays were done as follows. Opaque cells of the tester strain 3315 and experimental strains were cultured overnight in SD-complete liquid medium in a shaker at room temperature. Each of the experimental strains was mixed with the tester strain in fresh SD-complete liquid medium (107 cells/ml for each strain) and then incubated in the shaker for 48 h at room temperature. Cells were quantified with a microscopic counting chamber, collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended with water before plating onto SD-Trp− Lys−, SD-Arg−, or SD-Trp− Lys− Arg− medium for prototrophic selection and colony counting.

Pheromone response assay.

Strains were examined microscopically for shmoo formation after treatment with synthetic α-factor. Strains in opaque phase were incubated for 24 h at room temperature, diluted for a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05, and treated with pheromone (1 mg/ml) for 12 h before being photographed. Strains were visualized and photographed using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope with a magnification of ×400 using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics.

Alignment of G protein γ subunit sequences in ascomycete yeasts.

Multiple-protein-sequence alignments were performed with the MAFFT web application (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/) and visualized with Jalviewer (version 2). The protein sequences of the different ascomycete yeast species were downloaded from the Fungal Orthogroups Repository (http://www.broadinstitute.org/regev/orthogroups/) hosted by the Broad Institute, MIT. Pairwise protein alignments and identity percentages were established with BLASTP, which is from BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data have been deposited in the GEO database under accession number GSE54031.

RESULTS

ORF19.6551.1 (CaSTE18) encodes a typical Gγ subunit of heterotrimeric G protein in C. albicans.

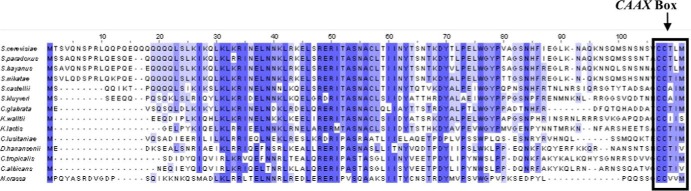

The C. albicans genome contains a single copy of a gene (STE18 [ORF19.6551.1]) that has the structural and expression characteristics of a typical γ subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins involved in mating. Expression of this gene is repressed by the a1/α2 repressor and is thus limited to MTL homozygous cells, in either the white or opaque state (32). This expression pattern is found for other genes such as FAR1 and STE4, which have been shown to be part of the mating pheromone response pathway in this organism (18, 33). Analysis of the deduced primary structure of the protein showed a high degree of identity with the ScGγ subunit of S. cerevisiae (40% identity and 58% similarity) and the KlGγ subunit of K. lactis (38% identity and 56% similarity), two other functionally characterized γ subunits of fungal mating response G proteins. CaGγ is 90 amino acids long and contains the conserved C-terminal CCAAX motif (CCTIV) that is a potential target for farnesylation at Cys87 and for palmitoylation at the preceding Cys86 (34) (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Alignment of candidate G protein γ subunit sequences encoded by 14 species of ascomycete yeasts. The deduced amino acid sequences of Gγ subunits encoded by the C. albicans STE18 gene and its homologs in 13 related ascomycete yeasts are shown, and the conserved C-terminal tail is highlighted.

The CaGγ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein is required for pheromone-induced gene induction and for mating in C. albicans.

In S. cerevisiae, the ScGγ subunit is required for mating and loss of ScGγ results in full sterility (7), but in K. lactis loss of the KlGγ subunit leads to only a slight mating defect (23). Mating in C. albicans requires both the CaGα and CaGβ subunits of the heterotrimeric G proteins (18); when the genes encoding the CaGα1 subunit or the CaGβ subunit were deleted, the cells became fully sterile. The effects of CaGγ inactivation have not been investigated. In order to ascertain the role of the G protein γ subunit in the pheromone response pathway in C. albicans, a null mutation was created in strain 3294 (MTLa). This ste18 null mutant was generated by a complete deletion of the whole ORF with HIS1 and URA3 cassettes by homologous recombination according to the strategy described in Materials and Methods. The correct insertion of the HIS1 and URA3 cassettes at the STE18 locus was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA (see the supplemental material).

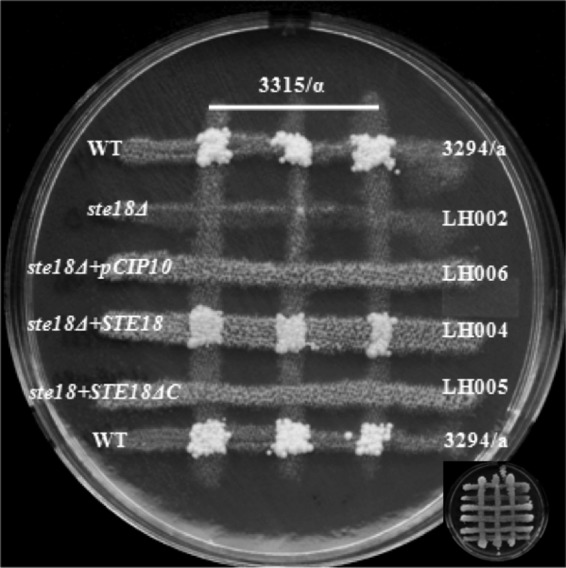

We then identified opaque derivatives of the ste18 null mutant strain on phloxine B plates and tested them for mating capacity. When the opaque ste18 null mutant strain was tested in a cross-patch mating assay, no prototrophic products derived from mating were detected, showing that the ste18 null strain was totally sterile (Fig. 2). In addition, the strain was totally defective in pheromone-induced gene expression, as treatment of opaque ste18 strains with synthetic α-factor failed to induce expression of any of a set of classic pheromone-responsive genes (Fig. 3). The cells were also defective in shmoo formation in the presence of α-factor (see the supplemental material). This sterile, nonresponsive phenotype was a result of the loss of Ste18p function in the mutant strain, as the reintroduction of a single copy of the STE18 gene at the RPS1 locus reestablished mating competence (Fig. 2). Thus, Ste18p, along with both the Gβ subunit Ste4p and the Gα subunit Cag1p, is a positive component in the pheromone response pathway of C. albicans.

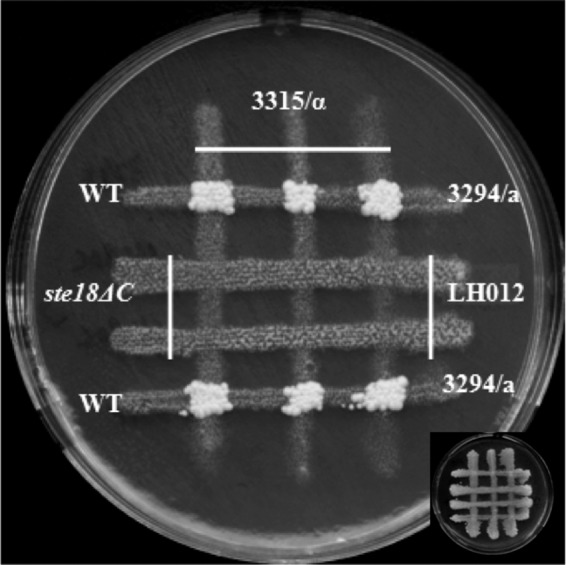

FIG 2.

Ste18 null mutant strains are sterile. Mating was assayed by auxotrophic marker complementation between strains of opposite mating types as described in Materials and Methods. The mating assay for MTLa ste18Δ strains, strains with STE18 reintegrated (ste18Δ + STE18), and strains with STE18ΔC reintegrated (ste18Δ + STE18ΔC) is shown. No colonies were formed by complementation of the ste18Δ strains (LH002 and LH006) and the strain with STE18ΔC reintegrated (LH005), while the strain with STE18 reintegrated (LH004) reverted the sterile phenotype. WT, wild type. The original mating cross is shown at the bottom corner.

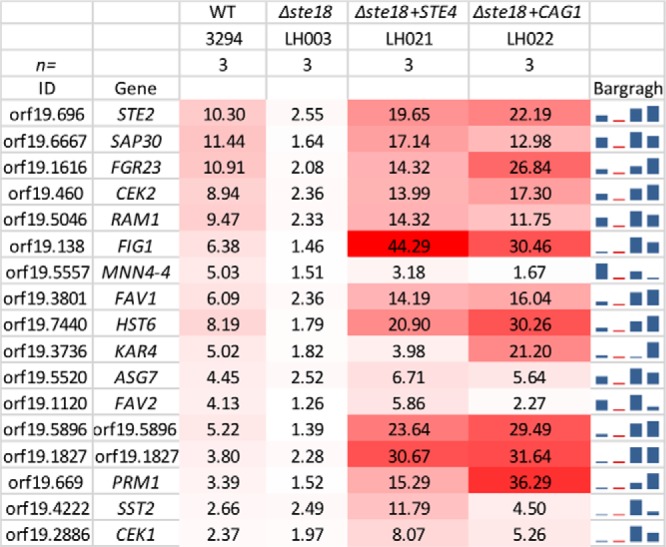

FIG 3.

Transcriptional response to pheromone treatment. The values shown represent the averages from 3 independent biological samples for 17 pheromone-inducible genes from C. albicans. The stronger signals have the deeper red color. The final column presents a graphical summary of the data. Deletion of the STE18 gene eliminates the pheromone induction of the genes, while ectopic expression of either STE4 or CAG1 enhances the responsiveness to induction by pheromone treatment. The complete data files are accessible at GEO through accession no. GSE54031.

The CAAX box of the CaGγ subunit is critical for mating in C. albicans.

The C terminus of the Gγ subunit is subjected to a complex posttranslational processing that generates a hydrophobic region of the protein through the addition of a methyl group and lipid moieties (for a review, see reference 35). As an initial means of investigating whether this modified domain is required for mating in C. albicans, we deleted the CAAX (cysteine, aliphatic, aliphatic, X) box (CCTIV) of both copies of the CaSTE18 gene (see the supplemental material). Opaque versions of doubly modified strains were identified on phloxine B plates to assess the role of the CaGγ subunit carboxy terminus in the mating process. Like the ste18 null mutant strain, the ste18ΔC mutant strain was unable to mate (Fig. 4). We also reintroduced a single copy of the STE18ΔC gene (without the last 21 bp) at the RPS1 locus in the ste18 null mutant strain, and this STE18ΔC strain was also unable to mate (Fig. 2). These results demonstrated that the carboxyl terminus of CaSte18p is critical for mating in C. albicans; reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis showed that the CAAX-deleted gene was expressed at normal levels (data not shown), so the mating defect could not be attributed to reduced expression of the mutant allele.

FIG 4.

Strains with C termini of CaGγ subunits (CCTIV) deleted are sterile. The mating assay was done as described in Materials and Methods. No prototrophic colonies from the ste18ΔC strain LH012 were detected after 5 days of incubation at room temperature. WT, wild type.

Ectopic expression of either the Gα subunit or the Gβ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein permits mating in the absence of the Gγ subunit in C. albicans.

In S. cerevisiae, overexpression of the STE4 gene product led to cell cycle arrest of haploid cells and suppressed the sterility of cells defective in the mating pheromone receptors encoded by the STE2 and STE3 genes (27). The Gβ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein triggered the pheromone response pathway in the absence of the Gγ subunit in K. lactis. Overexpression of the CAG1 gene and the STE4 gene product in wild-type strains of C. albicans did not result in any constitutive expression of pheromone-responsive genes or lead to increased shmoo formation or cell cycle arrest in the presence of the pheromone. In addition to this, overproduction of the STE4 gene did not suppress the sterility caused by deletion of the CAG1 gene, while the overexpression of the CAG1 gene was similarly unable to suppress the sterility caused by deletion of the STE4 gene (18). We assessed the role of ectopic expression of the CAG1 and STE4 genes in the absence of the STE18 gene in C. albicans by expressing either the CAG1 gene or the STE4 gene using the strong ACT1 promoter in the ste18 null mutant strain. This ectopic expression had been shown to increase gene expression from 7- to 15-fold in wild-type cells (18). Expression of either the CAG1 gene or the STE4 gene is able to suppress the mating defect caused by deletion of the Gγ subunit (Fig. 5 and 6).

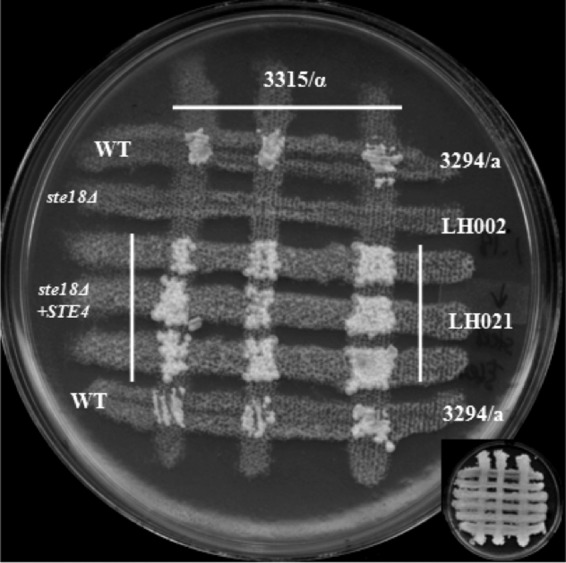

FIG 5.

Ectopic expression the STE4 gene in a ste18Δ strain reverts the sterile phenotype. The mating assay was done as described in Materials and Methods. Prototrophic colonies from the ste18Δ strain with the STE4 gene overexpressed were detected after 5 days of incubation at room temperature. WT, wild type.

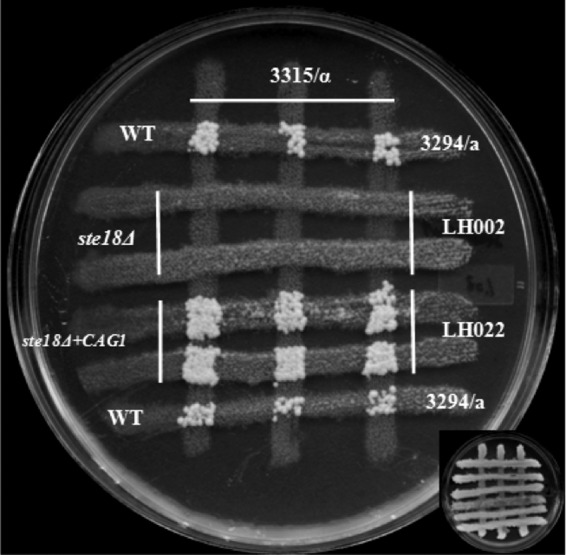

FIG 6.

Ectopic expression of the CAG1 gene in a ste18Δ strain reverts the sterile phenotype. The mating assay was done as described in Materials and Methods. Prototrophic colonies from the ste18Δ strain with the CAG1 gene overexpressed (LH022) were detected after 5 days of incubation at room temperature. WT, wild type.

We further assessed the consequences of the ectopic expression of the Gα or Gβ subunit on pheromone-induced gene expression in cells lacking STE18. The strains containing Gα or Gβ expressed under ACT1 control showed a higher level of gene induction in the presence of α-factor than did the wild-type cells (Fig. 3). This enhancement in response was associated with an increase in quantitative mating over wild-type levels as well (Table 3). Intriguingly, although all the responsive strains showed shmoo formation (see the supplemental material), they showed no evidence for a clear cell cycle arrest leading to the formation of halos in a classic halo assay (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Quantitative mating of wild-type strain 3294 and mutant strains

| Relevant genotype (strain) | Mating frequency (104, mean ± SD)a |

|---|---|

| Wild type (3294) | 2.63 ± 0.21 |

| Δste18 (LH003) | 0 |

| Δste18 + STE18 (LH004) | 6.84 ± 0.45 |

| Δste18 + STE18ΔC (LH005) | 0 |

| Δste18 + CIP10 (LH006) | 0 |

| STE18ΔC (LH012) | 0 |

| Δste18 + STE4 (LH021) | 12.0 ± 0.6 |

| Δste18 + CAG1 (LH022) | 4.83 ± 0.87 |

The STE18 replacement allele and the ectopically expressed CAG1 and STE4 genes enhance mating over the wild-type level. The mating frequency represents the number of observed prototrophic colonies divided by the number of potentially mating-competent input wild-type 3294 cells or input derivative 3294 cells.

DISCUSSION

The γ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins play key roles in the function of these important signaling molecules. Structural studies have shown that γ subunits form a very stable coiled-coil interaction with the N terminus of a Gβ subunit; this association is almost as stable as that which would be generated by a covalent linkage between the proteins (36). In addition, Gγ subunits typically undergo a complex posttranslational modification process of their carboxyl terminus. These proteins have a CAAX (cysteine, aliphatic, aliphatic, X) box motif at their C termini, and the cysteine residue of this motif is a target for the addition of both a prenyl (typically a farnesyl or geranylgeranyl) residue and a methyl residue (for a review, see reference 35). These modifications, and a further addition of a palmitoyl residue to a second cysteine often found adjacent to the CAAX box, generate a highly hydrophobic Gγ C terminus that helps to anchor the protein, together with the attached Gβ subunit, to cellular membranes (for a review, see reference 37).

Deletion of the Gγ subunit of the C. albicans mating response G protein generates sterility. In the present study, this test was done only in the MTLa background, but there is no reason to anticipate that the function is in any way mating type dependent. The positive functioning of the Gγ subunit is similar to the situation in S. cerevisiae, where the loss of the G protein γ subunit Ste18p results in the loss of mating competence (7). However, the role of the Gγ subunit in C. albicans contrasts with the role of Gγ subunit in K. lactis, where the loss of the Gγ subunit produces only a slight mating defect (23). Because S. cerevisiae and K. lactis diverged after the split from the common ancestor with C. albicans, it would appear that the ancestral Gγ subunit was essential for pheromone response and mating and that this role became reduced in the lineage leading to K. lactis. However, the observation that ectopic expression of either the Gα or Gβ subunit of the C. albicans heterotrimeric G protein can suppress the mating defect caused by deletion of the Gγ subunit suggests that the molecular role of the ancestral Gγ may actually be closer to that of the K. lactis protein than to that of the S. cerevisiae one. In S. cerevisiae, changes in the stoichiometry of the α or β subunit did not influence the need for the Gγ protein. Furthermore, engineering the Gβ subunit with the addition of a C-terminal membrane anchor was not sufficient to allow signal transduction, implying that the Gγ subunit played a role beyond simply serving as a membrane attachment (10). Because directly anchoring the Ste5p scaffold to the membrane through the addition of a membrane attachment motif activated the response pathway (10), a likely nonanchoring role of the Gγ subunit in yeast was to serve as part of the Ste5p binding interface. Considering that the overproduction of either the C. albicans Gα or Gβ subunit can bypass the need for CaSte18p, it is likely that Gγ is not an essential component in any Ste5p binding surface for this organism. The C. albicans Ste5p is considerably smaller than the yeast Ste5 protein, and the binding interface with the G protein, if any, is currently undefined (38, 39). Similarly, the K. lactis system does not have an essential role for the Gγ subunit, perhaps because the normal level of the Gα or the Gβ protein in this organism was sufficient to permit mating in its absence. K. lactis has a candidate Ste5 protein, but its molecular function has not yet been assessed, and its link, if any, to the G protein has not been established.

The observation that deletion of the CAAX box of CaSte18p causes sterility while overproduction of the Gα or Gβ subunit can suppress even complete deletion of the Gγ gene further suggests that membrane association of the G protein is a key component of function in the C. albicans mating pathway. It is possible that a critical role of this membrane association is to bring the Gβ subunit into proximity with a membrane-linked effector. This could explain the ability of overproduction of either Gβ itself or Gα to bypass the need for Gγ; subunit overproduction would generate more αβ dimers, and with Gα having its own membrane attachment capability due to myristoylation, this increases the overall amount of membrane-associated Gβ (Fig. 7). The C. albicans and K. lactis pathways may thus represent relatively unspecialized heterotrimeric G protein modules, with all subunits playing a positive role in the mating process and the Gγ subunit being relatively dispensable, while S. cerevisiae is more specialized, with the α and βγ subunits having distinct functions and the Gγ subunit being critical for effector activation. It is also intriguing that the ectopic expression of Gα or Gβ in the ste18 null mutant actually enhanced mating responsiveness measured by pheromone-induced gene expression, while similar ectopic expression in wild-type cells had little effect (18). This suggests that while the signaling from ectopically expressed Gα or Gβ in the absence of Ste18 is capable of allowing mating, the altered subunit stoichiometry affects the process quantitatively.

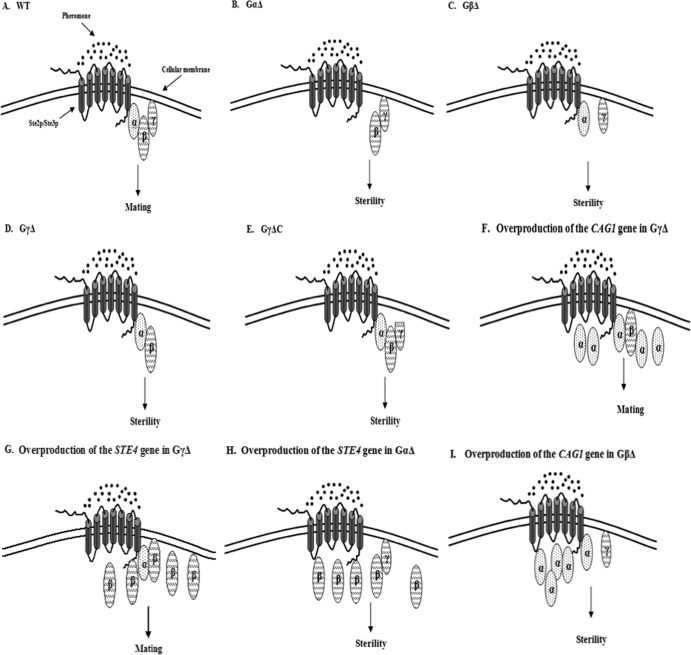

FIG 7.

Roles of G protein subunits in the mating process in C. albicans. All three G protein subunits are required for the mating (A). Loss of any one of them leads to full sterility (B, C, and D). The CAAX box of the Ste18p is critical for mating of C. albicans (E). Ectopic expression behind the strong ACT1 promoter of the STE4 gene did not rescue the sterility caused by absence of the Gα subunit, while the ectopic expression of the CAG1 gene was similarly unable to suppress the sterility caused by the absence of the Gβ subunit (H and I). Intriguingly, the ectopic expression of either the CAG1 gene or the STE4 gene is able to suppress the mating defect caused by deletion of the Gγ subunit (F and G).

Overall the functions of only a limited number of fungal mating pathway Gγ subunits have been assessed, but their roles have been found to be surprisingly variable. Less functional variability has been noted for higher eukaryotes. However, the mammalian Gβ5 subunit has been found to associate with regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins with a Gγ homology region, as well as with classical Gγ subunits (40), showing that even in higher eukaryotes, G protein function can accept variation in the involvement of the Gγ subunit. It is likely that continued genetic and biochemical analysis of the functions of G protein systems in fungal mating pathways will provide important insights into the functional plasticity of this important class of signaling molecules.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniel Dignard (Biotechnology Research Institute) for plasmids pl390 and pl391. We thank Cunle Wu (Biotechnology Research Institute) for helpful discussion about this study. We thank Hannah Regan (McGill University) and Pierre Cote (Concordia University) for their comments on the manuscript.

Hui Lu was supported by a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council on the MOE-NRC Research and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Work in the Whiteway lab was supported in part by CIHR grant MOP 42516.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00320-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oldham WM, Hamm HE. 2008. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:60–71. 10.1038/nrm2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tesmer JJ. 2010. The quest to understand heterotrimeric G protein signaling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:650–652. 10.1038/nsmb0610-650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprang SR. 1997. G protein mechanisms: insights from structural analysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:639–678. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollinger S, Hepler JR. 2002. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 54:527–559. 10.1124/pr.54.3.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietzel C, Kurjan J. 1987. The yeast SCG1 gene: a G alpha-like protein implicated in the a- and alpha-factor response pathway. Cell 50:1001–1010. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90166-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyajima I, Nakafuku M, Nakayama N, Brenner C, Miyajima A, Kaibuchi K, Arai K, Kaziro Y, Matsumoto K. 1987. GPA1, a haploid-specific essential gene, encodes a yeast homolog of mammalian G protein which may be involved in mating factor signal transduction. Cell 50:1011–1019. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90167-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteway M, Hougan L, Dignard D, Thomas DY, Bell L, Saari GC, Grant FJ, O'Hara P, MacKay VL. 1989. The STE4 and STE18 genes of yeast encode potential beta and gamma subunits of the mating factor receptor-coupled G protein. Cell 56:467–477. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90249-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardwell L. 2005. A walk-through of the yeast mating pheromone response pathway. Peptides 26:339–350. 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteway MS, Wu C, Leeuw T, Clark K, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Thomas DY, Leberer E. 1995. Association of the yeast pheromone response G protein beta gamma subunits with the MAP kinase scaffold Ste5p. Science 269:1572–1575. 10.1126/science.7667635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pryciak PM, Huntress FA. 1998. Membrane recruitment of the kinase cascade scaffold protein Ste5 by the Gbetagamma complex underlies activation of the yeast pheromone response pathway. Genes Dev. 12:2684–2697. 10.1101/gad.12.17.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metodiev MV, Matheos D, Rose MD, Stone DE. 2002. Regulation of MAPK function by direct interaction with the mating-specific Galpha in yeast. Science 296:1483–1486. 10.1126/science.1070540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breitkreutz A, Boucher L, Tyers M. 2001. MAPK specificity in the yeast pheromone response independent of transcriptional activation. Curr. Biol. 11:1266–1271. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butty AC, Pryciak PM, Huang LS, Herskowitz I, Peter M. 1998. The role of Far1p in linking the heterotrimeric G protein to polarity establishment proteins during yeast mating. Science 282:1511–1516. 10.1126/science.282.5393.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hull CM, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. 2000. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science 289:307–310. 10.1126/science.289.5477.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magee BB, Magee PT. 2000. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLalpha strains. Science 289:310–313. 10.1126/science.289.5477.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Lane S, Liu H. 2002. A conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for mating in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1335–1344. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. 2006. The role of nutrient regulation and the Gpa2 protein in the mating pheromone response of C. albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 62:100–119. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dignard D, Andre D, Whiteway M. 2008. Heterotrimeric G-protein subunit function in Candida albicans: both the alpha and beta subunits of the pheromone response G protein are required for mating. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1591–1599. 10.1128/EC.00077-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shpakov AO, Pertseva MN. 2008. Signaling systems of lower eukaryotes and their evolution. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 269:151–282. 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01004-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsueh YP, Xue C, Heitman J. 2007. G protein signaling governing cell fate decisions involves opposing Galpha subunits in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:3237–3249. 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savinon-Tejeda AL, Ongay-Larios L, Valdes-Rodriguez J, Coria R. 2001. The KlGpa1 gene encodes a G-protein alpha subunit that is a positive control element in the mating pathway of the budding yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. J. Bacteriol. 183:229–234. 10.1128/JB.183.1.229-234.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki L, Savinon-Tejeda AL, Ongay-Larios L, Ramirez J, Coria R. 2005. The Gbeta(KlSte4p) subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein has a positive and essential role in the induction of mating in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast 22:947–956. 10.1002/yea.1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarro-Olmos R, Kawasaki L, Dominguez-Ramirez L, Ongay-Larios L, Perez-Molina R, Coria R. 2010. The beta subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein triggers the Kluyveromyces lactis pheromone response pathway in the absence of the gamma subunit. Mol. Biol. Cell 21:489–498. 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soll DR. 2004. Mating-type locus homozygosis, phenotypic switching and mating: a unique sequence of dependencies in Candida albicans. Bioessays 26:10–20. 10.1002/bies.10379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zordan RE, Galgoczy DJ, Johnson AD. 2006. Epigenetic properties of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans are based on a self-sustaining transcriptional feedback loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12807–12812. 10.1073/pnas.0605138103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zordan RE, Miller MG, Galgoczy DJ, Tuch BB, Johnson AD. 2007. Interlocking transcriptional feedback loops control white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 5:e256. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiteway M, Hougan L, Thomas DY. 1990. Overexpression of the STE4 gene leads to mating response in haploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:217–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang G, Yi S, Sahni N, Daniels KJ, Srikantha T, Soll DR. 2010. N-Acetylglucosamine induces white to opaque switching, a mating prerequisite in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000806. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dignard D, El-Naggar AL, Logue ME, Butler G, Whiteway M. 2007. Identification and characterization of MFA1, the gene encoding Candida albicans a-factor pheromone. Eukaryot. Cell 6:487–494. 10.1128/EC.00387-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murad AM, Lee PR, Broadbent ID, Barelle CJ, Brown AJ. 2000. CIp10, an efficient and convenient integrating vector for Candida albicans. Yeast 16:325–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dignard D, Whiteway M. 2006. SST2, a regulator of G-protein signaling for the Candida albicans mating response pathway. Eukaryot. Cell 5:192–202. 10.1128/EC.5.1.192-202.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srikantha T, Borneman AR, Daniels KJ, Pujol C, Wu W, Seringhaus MR, Gerstein M, Yi S, Snyder M, Soll DR. 2006. TOS9 regulates white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1674–1687. 10.1128/EC.00252-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cote P, Whiteway M. 2008. The role of Candida albicans FAR1 in regulation of pheromone-mediated mating, gene expression and cell cycle arrest. Mol. Microbiol. 68:392–404. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirschman JE, Jenness DD. 1999. Dual lipid modification of the yeast ggamma subunit Ste18p determines membrane localization of Gbetagamma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7705–7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIntire WE. 2009. Structural determinants involved in the formation and activation of G protein betagamma dimers. Neurosignals 17:82–99. 10.1159/000186692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sondek J, Bohm A, Lambright DG, Hamm HE, Sigler PB. 1996. Crystal structure of a G-protein beta gamma dimer at 2.1A resolution. Nature 379:369–374. 10.1038/379369a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gautam N, Downes GB, Yan K, Kisselev O. 1998. The G-protein betagamma complex. Cell Signal. 10:447–455. 10.1016/S0898-6568(98)00006-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cote P, Sulea T, Dignard D, Wu C, Whiteway M. 2011. Evolutionary reshaping of fungal mating pathway scaffold proteins. mBio 2(1):e00230-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi S, Sahni N, Daniels KJ, Lu KL, Huang G, Garnaas AM, Pujol C, Srikantha T, Soll DR. 2011. Utilization of the mating scaffold protein in the evolution of a new signal transduction pathway for biofilm development. mBio 2(1):e00237-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie K, Allen KL, Kourrich S, Colon-Saez J, Thomas MJ, Wickman K, Martemyanov KA. 2010. Gβ5 recruits R7 RGS proteins to GIRK channels to regulate the timing of neuronal inhibitory signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 13:661–663. 10.1038/nn.2549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.