Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To promote the use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARC) (intrauterine devices and implants) and provide contraception at no cost to a large cohort of participants in an effort to reduce unintended pregnancies in our region.

METHODS

We enrolled 9,256 adolescents and women at risk for unintended pregnancy into the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a prospective cohort study of adolescents and women desiring reversible contraceptive methods. Participants were recruited from the two abortion facilities in the St. Louis region and through provider referral, advertisements, and word of mouth. Contraceptive counseling included all reversible methods, but emphasized the superior effectiveness of LARC methods (IUDs and implants). All participants received the reversible contraceptive method of their choice at no cost. We analyzed abortion rates, the percentage of abortions that are repeat abortions, and teenage births.

RESULTS

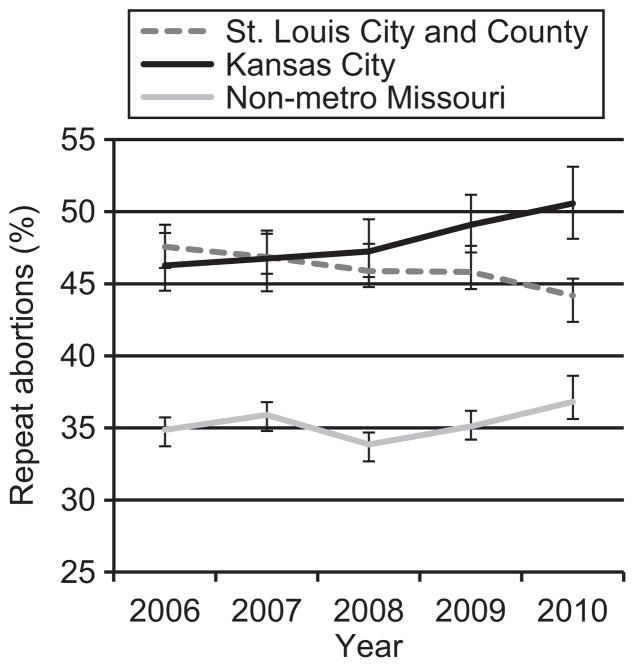

We observed a significant reduction in the percentage of abortions that are repeat abortions in the St. Louis region compared to Kansas City and nonmetropolitan Missouri (P < 0.001). Abortion rates of the CHOICE cohort were less than half the regional and national rates (P < 0.001). The rate of teenage birth within the CHOICE cohort was 6.3 per 1,000, compared to the U.S. rate of 34.1 per 1,000.

CONCLUSION

We noted a clinically and statistically significant reduction in abortion rates, repeat abortions, and teenage birth rates. Unintended pregnancies may be reduced by providing no-cost contraception and promoting the most effective contraceptive methods.

INTRODUCTION

Unintended pregnancies, pregnancies that are unwanted or mistimed at conception, are a costly public health problem. U.S. taxpayers pay approximately $11 billion dollars annually in costs associated with one million unintended births.1 The unintended pregnancy rate in the U.S. is significantly higher than in other developed countries.2 In the 2006–2008 cycle of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), 49% of all pregnancies were reported to be unintended. Of these, 29% were mistimed, 19% were unwanted, and 43% ended in abortion.3 Approximately half of unintended pregnancies result from non-use of contraception, and half result from inconsistent or incorrect use and contraceptive failure.4

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants, collectively referred to as long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARC), are highly effective, safe, and have high satisfaction and continuation rates.5 However, these methods are underutilized in the U.S. In other developed countries where IUDs are used more frequently, unintended pregnancy rates are lower.6 In fact, in a study examining global rates of unintended pregnancy between 1995 and 2008, North America was the only region of the world that did not see a decrease in the rates of unintended pregnancy.2 The most commonly used reversible contraceptive method in the U.S is the oral contraceptive pill (OCP), despite its “typical use” failure rate of 8–9% per year.7 However, IUDs and implants are over 20-times more effective at preventing pregnancy than OCPs, the contraceptive patch, and contraceptive vaginal ring.8

The objective of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE) was to promote the use of LARC methods and provide no-cost contraception to a large number of women and adolescents in our region in an effort to reduce unintended pregnancies. The primary population-based outcomes for our study were rates of teen births and percentage of abortions that are repeat abortions. We also estimated abortion rates in our metropolitan area and our cohort, and compared these rates to U.S. and regional abortion rates.

METHODS

We designed a prospective cohort study with two objectives: 1) to promote the use of the most effective contraceptive methods (IUDs and implants); and 2) to provide contraception at no cost to 10,000 female participants at-risk for unintended pregnancy in our region.9,10 Prior to initiating recruitment, we obtained approval from the Washington University Human Research Protection Office.

CHOICE participants met the following inclusion criteria: 1) age 14–45 years old; 2) desired reversible contraception; 3) not currently using a method or willing to switch to a new reversible contraceptive method; 4) no desire for pregnancy for at least 12 months; 5) planned to be sexually active with a male partner within the next 6 months; 6) resided in the St. Louis region; and 7) English or Spanish speaking. We excluded potential participants if they were surgically sterile. CHOICE participants were recruited by provider referral, newspaper reports and advertisements, study flyers, and word of mouth. In addition, we recruited eligible participants from local clinics and the two main abortion facilities in our region. All participants received the reversible contraceptive method of their choice at no cost for 3 years (first 5,090 participants) or 2 years (remainder of cohort). After completion of the study, participants could continue their IUD or implant, as these methods last 3 years (implant) to 10 years (copper IUD), but could no longer obtain contraception at no cost or change methods as part of the project.

All participants were read a brief script informing them of the effectiveness and safety of LARC methods at initial contact and completed an in-depth, evidence-based, contraceptive counseling session at enrollment. 10 Participants were offered all Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptive methods and could choose any method. Each participant provided written informed consent and was followed prospectively for the duration of follow-up.

Our primary population-based outcomes included teenage births and repeat abortions as proxies for unintended pregnancies. Since participant recruitment sites included two regional abortion facilities, we believed our greatest population effect would be on repeat abortions, or the percentage of abortions that are performed in adolescents and women with a previous abortion. Thus, one of our primary outcomes of interest was the percentage of abortions that are repeat abortions. We compared repeat abortion data in the St. Louis region to Kansas City, Missouri and non-metropolitan Missouri. Kansas City is of similar size and demographic profile to St. Louis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of St. Louis, Kansas City, and the State of Missouri

| Characteristic | St. Louis City and County | Kansas City | State of Missouri |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total population (n) | 1,318,248 | 459,787 | 5,988,927 |

| Under 18 years | 22.9 | 24.2 | 23.8 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 63.9 | 59.2 | 82.8 |

| Black | 28.8 | 29.9 | 11.6 |

|

| |||

| Persons below poverty level | 13.6 | 18.1 | 14 |

|

| |||

| High school graduates, % of persons aged 25 or older | 88.1 | 86.4 | 86.2 |

Data are % unless otherwise specified.

Data from the following sources: U.S. Department of Commerce: United States Census Bureau. State & County QuickFacts, St. Louis, Missouri. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/29/29189.html. Retrieved September 7, 2012; U.S. Department of Commerce: United States Census Bureau. State & County QuickFacts, St. Louis (city), Missouri. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/29/2965000.html. Retrieved September 7, 2012; U.S. Department of Commerce: United States Census Bureau. State & County QuickFacts, Kansas City (city), Missouri. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/29/2938000.html. Retrieved September 7, 2012; and U.S. Department of Commerce: United States Census Bureau. State & County QuickFacts, Missouri. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/29000.html. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

While not an a priori primary outcome of interest, we also estimated abortion rates as the majority of abortions result from unintended pregnancies. We obtained abortion data from two sources. Reproductive Health Services (RHS) of Planned Parenthood is the major abortion provider in the St. Louis area and represents 90% of the abortions among St. Louis-area females reported to the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (MDHSS). We obtained the total number of abortions per year among Missouri residents served at Reproductive Health Services grouped by county-level residence. We also obtained the total number of abortions per year and the number of abortions among females who reported a prior abortion at the time of the current abortion at the state-level from MDHSS. The MDHSS also maintains reciprocal vital statistics reporting with states to obtain information on abortions that occur to Missouri residents at facilities located outside of Missouri. MDHSS reported the total and repeat abortion numbers by four geographic locations based on patient zip code and grouped by St. Louis City or County (our study catchment area), Kansas City, and all remaining zip codes grouped as non-metropolitan Missouri.

Abortion rates among participants aged 15–44 years and births among participants aged 15–19 years within CHOICE were compared to regional and national rates. Because the CHOICE cohort represents a higher-risk population (median age of 25 years and 50% black) than the general population, we standardized the CHOICE abortion rate to the age and racial (black and white) distribution of females who reside in the St. Louis region using data from the 2010 U.S. Census (direct standardization). We compared the CHOICE standardized rate to the St. Louis regional rate using data from MDHHS and to the national rate using the most recent published data from 2008.8

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software, version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The significance level was set at 0.05. Means, standard deviations, frequencies and percentages were used to describe the demographic characteristics of the study participants. We calculated 95% confidence intervals around the percentage of abortions that were repeat for each year from 2006 through 2010. We used a Pearson chi-square test to determine a significant difference in the proportion of repeat abortions each year between the St. Louis region and Kansas City and a Mantel-Haenszel score test for trend of odds of repeat abortions for 2006–2010 for the St. Louis, Kansas City, and non-metropolitan Missouri regions, individually. We used negative binomial regression models to estimate time trend for total abortions in St. Louis region and non-St. Louis Missouri. We estimated the population attributable risk by calculating the risk difference between CHOICE and the St. Louis region rates and multiplying by the St. Louis region population divided by 1,000, and calculated the number needed to treat by taking the inverse of the absolute risk reduction. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat were estimated using the Bender method.9

For sample size calculations, we considered a 50–60% within the study population or a 6–7% St. Louis region reduction in teen births (baseline rate 126 per 1,000) and repeat abortion (baseline rate 430 per 1,000) to be of clinical and public health importance. Further, we assumed no change in the remainder of the St. Louis population not participating in the study, an alpha of 0.05 and power of 80%. Our intent was to interact with 11% of the population in the region at greatest risk for unintended pregnancy. Further, we estimated that 10% of the cohort would choose an IUD and 3% of our cohort would choose an implant, a rate almost double that of current IUD and implant use in the U.S.10 Based on these assumptions, an enrollment of 2,000 participants aged 15–19 years would represent 11% of the population at risk for teenage pregnancy, while an enrollment of 5,000 participants with a history of abortion would also reach 11% of the population at risk of repeat abortion. The uptake of IUD and implant was much greater than originally predicted,11 leading to greater observed reductions in pregnancy risk among the accrued study population than anticipated, allowing us to exceed our initial targets for population effect.

RESULTS

Between August 2007 and September 2011, 9,256 adolescents and women enrolled in CHOICE; of which 16% were recruited at the abortion facilities. The baseline demographic and reproductive characteristics of the cohort are provided in Table 2. The mean age of the total population was 25 years, 51% were African American, 35% had a high school education or less, 37% received public assistance, and 39% had trouble paying for basic expenses. Forty-seven percent were nulliparous, 63% had a prior unintended pregnancy. Participants chose the following contraceptive methods at baseline: 46% levonorgestrel IUD, 12% copper IUD, 17% subdermal implant, 9% OCPs, 7% contraceptive vaginal ring, 7% depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and 2% contraceptive patch. Thus, 75% of our study population chose a LARC method. Participants recruited at the abortion clinics were more likely to be black, report a high school education or less, experience trouble paying for basic necessities, receipt of public assistance, or no insurance, and report greater parity and a history of 3 or more unintended pregnancies. We also found that these participants were more likely to choose a LARC method at enrollment compared to adolescents and women enrolled at the other recruitment clinics (84.5% versus 72.9%, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic and Reproductive Characteristics of Women and Adolescents Enrolled in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (n=9,256)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Enrollment location | ||

| Abortion clinics | 1501 | 16.2 |

| University or community clinics | 7755 | 83.8 |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 14–17 | 484 | 5.2 |

| 18–20 | 1547 | 16.7 |

| 21–25 | 3564 | 38.5 |

| 26–35 | 3026 | 32.7 |

| 36–45 | 635 | 6.9 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| Black | 4670 | 50.5 |

| White | 3870 | 41.8 |

| Other | 715 | 7.7 |

|

| ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 475 | 5.1 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 3205 | 34.6 |

| Some college | 3902 | 42.2 |

| College or more | 2146 | 23.2 |

|

| ||

| Receiving public assistance* | 3442 | 37.2 |

|

| ||

| Trouble paying basic expenses† | 3639 | 39.4 |

|

| ||

| Insurance | ||

| None | 3782 | 41.1 |

| Private | 3957 | 43.1 |

| Public | 1455 | 15.8 |

|

| ||

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 4369 | 47.2 |

| 1 | 2279 | 24.6 |

| 2 | 1606 | 17.4 |

| 3 or more | 1002 | 10.8 |

|

| ||

| Unintended pregnancies | ||

| 0 | 3413 | 36.9 |

| 1 | 2492 | 26.9 |

| 2 | 1551 | 16.8 |

| 3 or more | 1794 | 19.4 |

|

| ||

| Ever had an abortion including at time of study enrollment | 3871 | 41.8 |

|

| ||

| History of STI‡ | 3746 | 40.5 |

|

| ||

| Baseline chosen method | ||

| Levonorgestrel intrauterine device | 4261 | 46.0 |

| Copper intrauterine device | 1101 | 11.9 |

| Etonogestrel implant | 1566 | 16.9 |

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate | 638 | 6.9 |

| Oral contraceptive pill | 874 | 9.4 |

| Contraceptive vaginal ring | 646 | 7.0 |

| Contraceptive patch | 166 | 1.8 |

| Natural family planning | 3 | <0.01 |

| Diaphragm | 1 | <0.01 |

Current receipt of food stamps, Woman Infants and Children (WIC), welfare, or unemployment.

Transportation, housing, health or medical care, or food.

Self-reported of history of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, trichomoniasis, genital herpes, human papillomavirus or human immunodeficiency virus.

Some variables do not sum to total sample size due to unanswered survey items, missing data, or both.

We evaluated teenage birth (births per 1,000 females aged 15–19) as a proxy for unintended pregnancy, as up to 80% of these births are unintended.3, 12 The number of teenage births in the U.S. has markedly decreased in the past several years, with a 44% drop between 1991 and 2010 to a level of 34.3 per 1,000.13 The birth rate among participants aged 15–19 years within the CHOICE cohort was 6.3 per 1,000, a rate far below the national level, compared to the U.S. rate of 34.1 per 1,000.

Figure 1 shows the number of abortions among Missouri residents reported by Reproductive Health Services stratified by region (St. Louis City and County versus the rest of Missouri). Between 2008 and 2010, the number of abortions performed at Reproductive Health Services among women and teenagers who resided in St. Louis City and County declined by 20.6% (P < 0.001), compared to no appreciable change (0%, P = 0.39) in the abortion number among women and teenagers who resided in the rest of Missouri.

Figure 1.

Number of abortions to Missouri residents reported by Reproductive Health Services, 2006–2010. P value for test of trend over time: St. Louis City and County, P<.001; all other Missouri residents, P=.39.

Our primary outcome of interest was the percentage of abortions that are repeat abortions for of the following reasons: First, this information is tracked by providers and in government statistics. Second, our objective was to have the maximum population effect through the provision of our intervention to participants at highest risk for unintended pregnancy. Women and teenagers seeking pregnancy terminations are at risk for future unintended pregnancy and repeat abortion as well as potentially motivated to seek contraceptive services. Using vital statistics data from the state health department, Figure 2 shows a significant difference in the proportion of repeat abortions between the St. Louis region and Kansas City in 2009 (P = 0.02) and 2010 (P < 0.01). We also detected a significant decline in the proportion of repeat abortions over time in the St. Louis region (P = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Abortions (%) that are repeat abortions in St. Louis City and County compared to Kansas City and nonmetropolitan Missouri, 2006–2010. P=.02 comparing St. Louis and Kansas City in 2009, and P<.001 in 2010. P value for test of trend over time (2006–2010): St. Louis, P=.002; Kansas City, P=.003; nonmetropolitan Missouri, P=.18.

Between 2008 and 2010, abortion rates in CHOICE participants ranged from 4.4 to 7.5 per 1,000 after adjusting for age and race (Table 3). These rates are considerably less than the rates in St. Louis City/County for the same years (P < 0.001), and far below the national rate of 19.6 per 1,000. Using this data, we then estimated the difference in abortion rates and number of abortions prevented each year if CHOICE were available to the entire population of the region. Based on the number needed to treat (NNT), one abortion could be prevented for every 79–137 women and teenagers provided the CHOICE intervention.

Table 3.

Abortion Rates per 1,000 Women and Adolescents in CHOICE, St. Louis, and the United States, and Estimated Population Effect of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project

| Year | CHOICE vs. St. Louis Region (City and County) | National Rate|| | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHOICE Rate* | Region Rate† | P | Abortions Prevented‡ | Number Treated to Prevent One Abortion | |||

| NNT§ | 95% CI | ||||||

| 2008 | 4.4 | 17.0 | <0.001 | 3124 | 79 | 44–255 | 19.6 |

| 2009 | 7.5 | 14.8 | <0.001 | 1810 | 137 | 97–224 | NA |

| 2010 | 5.9 | 13.4 | <0.001 | 1860 | 133 | 99–213 | NA |

NNT, number needed to treat; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

Among Black and White, aged 15–44, adjusting for age and race using 2010 census data

Among Black and White, aged 15–44, denominator is 2010 census data

CHOICE compared to St. Louis rate, number of abortions prevented in St. Louis city or county.

CHOICE compared to St. Louis rate, number needed to treat to prevent one abortion.

Among all races aged 15–44.

DISCUSSION

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently recommended that eight primary preventive health services for women be covered without cost to patients under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA).14 Among these eight services, the IOM recommended “a fuller range of contraceptive education, counseling, methods, and services so that women can better avoid unwanted pregnancies and space their pregnancies to promote optimal birth outcomes.” As a result, all FDA-approved contraceptive methods would be covered without cost. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project essentially simulated this recommendation in our region for reversible contraceptive methods. All women received any FDA-approved contraceptive method of their choice, as well as the ability to change methods at no cost. In addition, the project provided education to promote the use of the most effective contraceptive methods, IUDs and implants, in an effort to alter population outcomes.

There are few studies that have investigated whether increasing the uptake of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods decreases unintended pregnancy. A recent analysis of the family planning expansion program in California known as the Family Planning, Access, Care and Treatment Program (Family PACT) examined the association between increased contraceptive access and unintended pregnancy.15 Using a Markov model, the authors estimated that increasing contraceptive access to low-income women averted more than 286,000 unintended pregnancies. Interestingly, uptake of LARC was substantially lower among Family PACT participants than among CHOICE participants; however, the increased access to no-cost contraception still resulted in a significant reduction in the number of unintended pregnancies. A qualitative study of women undergoing abortion found that there was a high level of interest in LARC methods for post-abortion contraception, but the majority of women also identified cost as a barrier to obtaining a LARC method.16 Participation in CHOICE provided participants with access to IUDs and implants that they otherwise might not have had, including teenagers and women recently post-abortion who are at high risk for repeat unintended pregnancy.

The birth rate to females 15–19 years of age in our cohort is markedly less than the U.S. rate, despite a remarkable decline in teenage births nationally.13 We also noted a substantially lower abortion rate in our cohort compared to regional and national statistics, and a significant decline in repeat abortions in the St. Louis region. Increasing access to the most effective contraceptive methods by removing cost and access as barriers has greatly increased the number of adolescents and women in the St. Louis region using the most effective methods of birth control. Providing no-cost contraception and promoting the use of highly effective contraceptive methods has the potential to reduce unintended pregnancies in the U.S. In fact, based on our calculations in Table 3, changes in contraceptive policy simulating the Contraceptive CHOICE Project would prevent as many as 41% to 71% of abortions performed annually in the U.S.

The strengths of our study include the prospective design of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a large sample with a high uptake of the most effective contraceptive methods, the use of systematically collected state-mandated data, and partnership with community clinics serving adolescents and women at highest risk for unintended pregnancy. Our study also has several limitations. Intendedness of pregnancy is not captured in the state vital statistics; therefore, we used proxy markers of unintended pregnancy. However, teenage births, abortions, and repeat abortions are indicators of unintended pregnancy.17 Also, we previously compared CHOICE participants to NSFG participants and found that they were similar except that CHOICE participants were more likely to be African-American, single, and have a lower income;18 all characteristics associated with an increased risk for unintended pregnancy.3 Thus, while our CHOICE cohort may not be similar demographically to many other geographic areas limiting the study’s generalizability, CHOICE participants are at high risk for unintended pregnancy. Another limitation is that the analyses comparing repeat abortion in the St. Louis region to Kansas City and non-metropolitan Missouri is essentially an ecological study. There may be several factors that affect the rates of repeat abortion, such as the economic recession, federal changes in Title X funding for family planning, and Missouri state laws that limit access to abortion. It is not possible to conclude that the changes observed in repeat abortion were due solely to the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. However, the weight of the evidence including a marked reduction in teenage births and abortion rates compared to regional and national statistics provides evidence of a population impact of the CHOICE intervention.

Unintended pregnancy remains a stubborn problem in the U.S., with higher proportions among adolescents and young women, racial and ethnic minorities, women with less education and lower socioeconomic status.3 Approximately half of unintended pregnancies are the result of contraceptive failure,19 with the majority of women using reversible contraception using the pill or the condom.7 Many family planning experts believe that LARC methods should be first-line contraceptive options, and increased uptake of LARC methods is essential to decreasing the rate of unintended pregnancy.20–22 In addition, since LARC methods have been shown to have higher continuation rates than other reversible methods, the number of adolescents and women using no contraception would decline, further decreasing the unintended pregnancy rate.5 Increased access to contraception, particularly highly-effective LARC methods, and providing contraception at no cost may result in a significant decrease in the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project is funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation. The authors would like to thank the entire staff of the CHOICE team as well as the thousands of participants in the project.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Madden is on the Speaker’s Bureau for Bayer Pharmaceuticals. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gold RB, Sonfield A. Publicly funded contraceptive care: a proven investment. Contraception. 2011;84:437–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41:241–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84:478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost JJ, Darroch JE, Remez L. Issues Brief (Alan Guttmacher Inst) 2008. Improving contraceptive use in the United States; pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and Satisfaction of Reversible Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajos N, Leridon H, Goulard H, Oustry P, Job-Spira N. Contraception: from accessibility to efficiency. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:994–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital Health Stat. 2010;23:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RK, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in abortion rates between 2000 and 2008 and lifetime incidence of abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1358–66. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c405e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender R. Calculating confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22:102–10. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, editor. Use of Contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Hyattsville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: Reducing Barriers to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115, e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissin DM, Anderson JE, Kraft JM, Warner L, Jamieson DJ. Is there a trend of increased unwanted childbearing among young women in the United States? J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ. Birth rates for u.s. Teenagers reach historic lows for all age and ethnic groups. NCHS Data Brief. 2012:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Preventive Services for Women; Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster DG, Biggs MA, Rostovtseva D, Thiel de Bocanegra H, Darney PD, Brindis CD. Estimating the fertility effect of expansions of publicly funded family planning services in California. Women Health Iss. 2011;21:418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose SB, Cooper AJ, Baker NK, Lawton B. Attitudes toward long-acting reversible contraception among young women seeking abortion. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:1729–35. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones R, Singh S, Finer L, Frohwirth L. Repeat abortion in the United States: Occasional Report. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kittur ND, Secura GM, Peipert JF, Madden T, Finer LB, Allsworth JE. Comparison of contraceptive use between the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and state and national data. Contraception. 2011;83:479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumenthal PD, Voedisch A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy: increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:121–37. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleland K, Peipert JF, Westhoff C, Spear S, Trussell J. Family planning as a cost-saving preventive health service. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:e37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1104373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. ACOG Committee Opinion no 450: Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1434–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]