INTRODUCTION

Reward processing comprises what individuals will work for, such as food, money, or social approval. Patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) exhibit overeating and poor financial decisions, including overspending and impulsive purchases in spite of negative consequences. On gambling tasks bvFTD patients choose options with high risk of monetary loss but with large possible gains1, 2. Social functions are particularly affected in bvFTD and patients are often cold and withdrawn, suggesting a lack of reward through interpersonal interaction. By contrast, early in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) social skills tend to be more intact. AD patients also make financial errors, but for different reasons3. Amnestic mild cognitive impairment patients who may develop AD are more motivated by avoiding monetary loss than by monetary gain4.

The mechanisms underlying decision-making deficits in bvFTD and AD are potentially different, reflecting differing contributions from a heightened desire for gain, loss insensitivity, or cognitive deficits related to executive function. In addition, the impact of social rewards may differ between disorders. An association between reward and social cognition is plausible, since reward processing involves a distributed network including ventral striatum, orbitofrontal cortex, insula, and anterior cingulate, and there is some overlap between these regions and those required for social cognition. Experimental comparison of monetary and social reward processing anatomy showed largely overlapping results5. Little is known about how systems mediating rewards and social cognition interact to impact behavior.

Our objective was to apply a modified version of an established reward task, the Monetary Incentive Delay (MID)6, including social and monetary rewards5 to bvFTD and AD patients to determine whether they are motivated more by seeking potential gain or avoiding potential loss, and whether this differs if the reward is monetary or social. We hypothesized that bvFTD patients would be less sensitive to potential monetary loss based on their real-life financial decisions3 and gambling task performance and would be unmotivated by social rewards, whereas AD patients would be more motivated by avoiding monetary loss.

METHODS

Subjects

Patients with bvFTD, AD, and normal controls were recruited to participate (Supplemental Digital Content 1 for subject diagnostic evaluation and inclusion criteria). Written informed consent was obtained from patients or surrogates according to procedures approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research. 66 subjects completed the task successfully and were included in the analysis, 14 with bvFTD, 11 AD, and 41 controls. Demographic features of the three groups are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Group Demographics

| bvFTD subjects |

AD subjects | Normal controls |

Statistical comparison |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 14 | 11 | 41 | ||

| Male gender (%) | 11 (78.6%) | 7 (63.6%) | 18 (43.9%) | χ2=5.499 | .064 |

| Age | 58.4 (8.84) | 64.6 (8.62) | 70.5 (5.14) | F(2,63) = 18.054 | < .001 |

| Education (years) | 16.00 (2.54) | 17.45 (2.25) | 17.78 (2.06) | F(2,63) = 3.446 | .038 |

| MMSE (/30) | 26.86 (1.56) | 23.82 (3.09) | 29.37 (0.94) | F(2,63) = 55.43 | <.001 |

MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination

Data for age, education, and MMSE are shown as mean (standard deviation)

Procedure

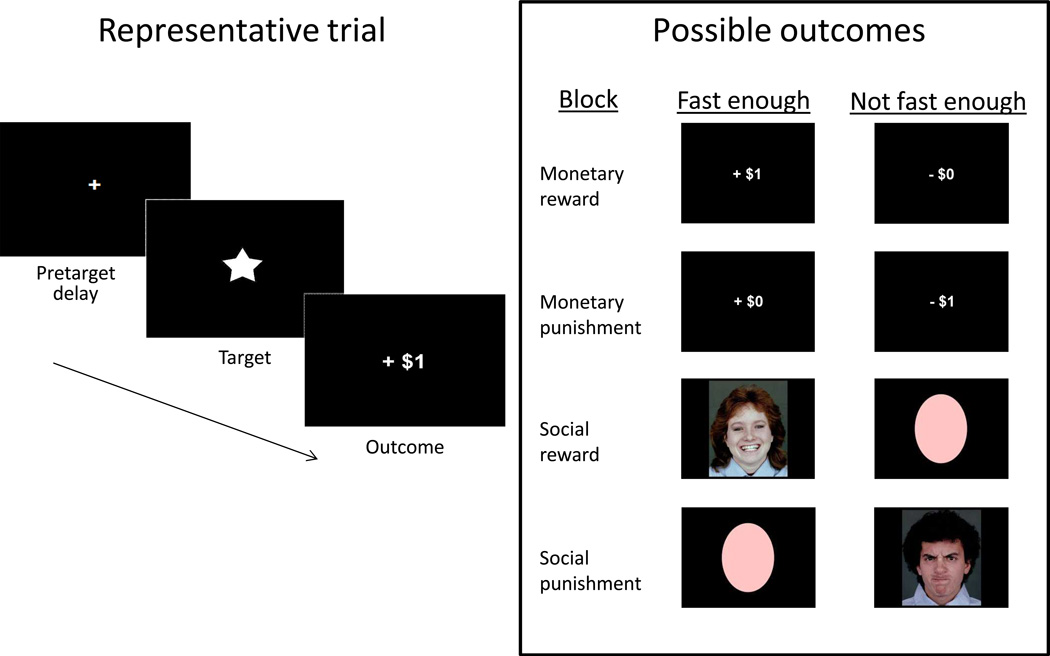

Subjects participated in a computer-based reaction time task adapted from the MID6 (Figure 1 and Supplemental Digital Content 1 for task details). Two task blocks evaluated monetary rewards: a monetary win and a monetary loss condition. The other two assessed social rewards: social win and social loss. Subjects were instructed to push the spacebar immediately when a target appeared onscreen. Success on each trial was based on responding before the target disappeared and feedback was given after each trial. The duration the target remained onscreen was adjusted throughout the task to ensure a 66% success rate. Subjects were paid cash based on total earnings during the monetary blocks. Feedback on social blocks consisted of smiling faces, angry faces, or neutral ovals.

Figure 1.

Incentive delay task design. The structure of a representative trial is shown on the left. On the right the possible outcomes are shown for each of the four task blocks depending on whether the subject pressed the spacebar fast enough or not.

Statistics

Statistics were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20. The main analysis was a mixed-model, repeated measures analysis of covariance with reward type (money or social) and reward direction (gain or loss) as independent variables. Reaction time after target appearance was the dependent variable. Groups were compared by univariate analysis of variance for age, education, and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)7 with between group differences assessed post hoc with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Gender was compared by chi squared analysis. Factors that significantly varied among the three groups were included as covariates. Data were excluded for subjects who failed to press the button during at least 20% of trials, which suggested they were not correctly following task directions. This occurred in one control, three bvFTD, and five AD subjects (not included in number of subjects listed above or Table 1).

RESULTS

Education differed among groups with controls being significantly more educated than bvFTD (p=.033). Gender did not differ significantly among groups. Age varied significantly and controls were older than bvFTD (p<.001) and AD (p<.05). MMSE varied among all groups with each group significantly differing from the others (all p<.001). Age, education, and MMSE were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

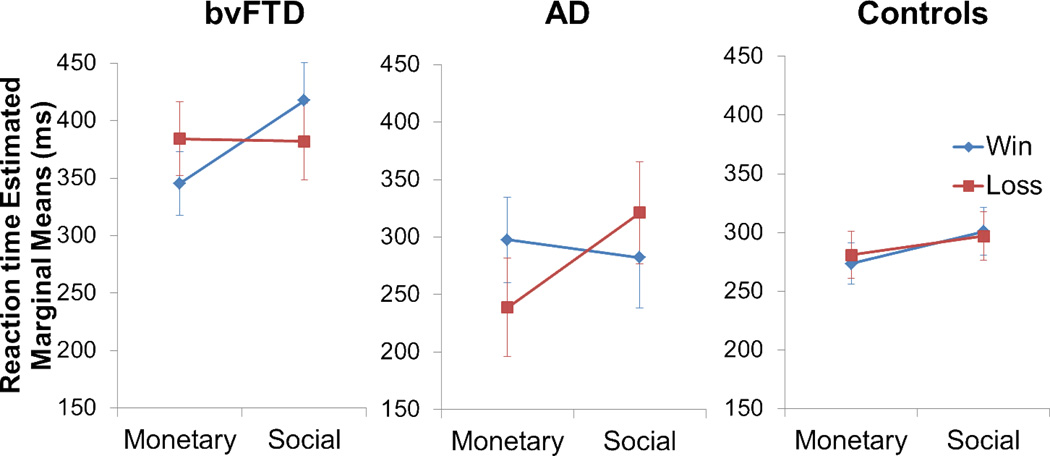

There was a significant main effect of reward type (F(1,60)=5.97, p<.05) with shorter reaction times on monetary trials than social trials. Main effects of reward direction were not significant (p>.05). There was a significant diagnosis X reward type X reward direction interaction (F(2,60)=3.29, p<.05). Among bvFTD patients, reaction times were faster for monetary win than monetary loss. Among AD patients, reaction times were faster for monetary loss than monetary win. These patterns reversed when the social blocks were considered. The bvFTD patients reacted faster for social loss than for social win. AD patients reacted faster for social win than social loss. Mean reaction times and the interaction are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect. The mean reaction times for behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) (left), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (center), and normal controls (right) are displayed for each of the four conditions. Bars indicate standard error. Results are displayed corrected for age, education, and Mini-Mental State Examination Score.

Additional analyses were performed looking only at bvFTD and AD. On social trials there was a significant diagnosis X reward direction interaction (F(1,20)=0.88, p<.05), again illustrating that AD subjects reacted faster for social win than social loss and bvFTD performed the opposite. On the social win block, AD subjects were faster than bvFTD, though not reaching significance (F(1,20)=3.18, p=.09). On monetary trials, there was a trend for the diagnosis X reward direction interaction (F(1,20)=3.09, p=.094), suggesting that bvFTD subjects react faster for monetary win than monetary loss and AD show the opposite pattern. Consistent with that trend, AD subjects reacted significantly faster than bvFTD subjects on the monetary loss block (F(1,20)=5.20, p<.05).

DISCUSSION

The study’s main finding was a significant interaction between diagnosis, reward type (monetary or social), and reward direction (gain or loss). Though patients with bvFTD were slower than the other groups, they reacted more quickly when a monetary win was possible than for any other outcome. Their reactions were comparably slow in both loss conditions, but even slower to attain social reward. AD patients showed the opposite pattern to bvFTD. They reacted more quickly to avoid monetary loss than to gain monetary reward. In the social conditions they reacted faster to gain social reward than to avoid negative social feedback. Controls showed little difference between win and loss trials, but were slightly faster to win money than to avoid losing it.

These findings suggest an imbalance in bvFTD between sensitivity to monetary reward and loss. The pattern exhibited by bvFTD patients during the monetary conditions is consistent with their risky decisions in gambling tasks1, 2. Unlike gambling tasks, which require widespread cognitive function8, the MID assesses reward behavior without requiring conscious decisions or learned strategies. The indifference to social reward also corresponds with personality changes in the illness and suggests an additional reason for patients’ socially inappropriate behaviors.

The results among AD patients on the monetary conditions are similar to a prior study in mild cognitive impairment that showed more motivated performance when monetary loss is threatened than for gain4. AD patients in this study were also motivated by positive social reinforcement. Patients with AD are more socially intact than those with bvFTD, displaying more empathy and mutual gaze with partners9, consistent with seeking smiling faces as rewards.

This opposite pattern of reward sensitivity between bvFTD and AD reflects differing anatomic susceptibility between the two pathologies. AD patients, who show degeneration in default mode network structures have preserved or enhanced connectivity of the ventral salience network, which is important for socioemotional functioning. The reciprocal pattern occurs in bvFTD; salience network structures including frontal insula and anterior cingulate cortex are affected early with the default mode network preserved. Insular degeneration might relate to bvFTD patients’ greater motivation to gain money than avoid losing it, as this structure has been implicated in representing negative consequences and anticipating loss.

Controls’ reactions differed little between win and loss blocks for each reward type. Their slightly faster performance for monetary win compared to monetary loss is consistent with prior MID findings in older adults, who had similar fMRI activation when anticipating gain as younger adults but less activation when anticipating loss10.

As has previously been observed using this task5, patients were slower during social than monetary conditions. This could reflect the potency of the cues. Social feedback through on-screen images might not be as salient as money, which participants correctly understood they would receive upon completion. Prior studies with this task have demonstrated fMRI activation of the same reward processing structures with feedback in the form of faces as with money5.

Study limitations included small sample size and the potential for subjects’ impairment to impact performance. Disease-related emotional face processing deficits may affect bvFTD and AD subject performance on social conditions and are an important consideration for explaining social behavior changes and apparent sensitivity to social reward in each illness. If emotional face recognition influenced findings, bvFTD performance differed from expectations based on the inconsistently-reported impaired recognition of negative affect in the illness.

Further directions will include validating these findings using other decision-making measures, separating reward oversensitivity from punishment insensitivity in bvFTD, and elucidating the anatomic mechanisms behind these behaviors. This study suggests that the processing of monetary and social rewards differs between bvFTD and AD, reflecting their differing patterns of neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

sources of funding:

The authors wish to thank Brian Knutson, PhD who consulted on the adaptation of the study task. Funding support for this study came from NIH grants R01-AG022983-07, P01-AG1972403, P50-AG023501, and through the Larry Hillblom Foundation. Dr. Perry reports no disclosures. Dr. Sturm is supported by 1K23AG040127. Ms. Wood reports no disclosures. Dr. Miller serves as board member on the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation and Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, serves as a consultant for TauRx, Ltd., Allon Therapeutics, the Tau Consortium and the Consortium for Frontotemporal research, The Siemens MIBR (Molecular Imaging Biomarker Research) Alzheimer’s Advisory Group, has received institutional support from Novartis, and is funded by NIH grants P50AG023501, P01AG019724, P50 AG1657303, and the state of CA. Dr. Kramer is funded by NIH grant R01-AG022983-07.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Supplemental Digital Content

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Text that gives details of study subjects and description of the study task. Pdf

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahman S, Sahakian BJ, Hodges JR, et al. Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 8):1469–1493. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.8.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torralva T, Kipps CM, Hodges JR, et al. The relationship between affective decision-making and theory of mind in the frontal variant of fronto-temporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiong W, Hsu M, Wudka D, et al. Financial errors in dementia: Testing a neuroeconomic conceptual framework. Neurocase. 2013 doi: 10.1080/13554794.2013.770886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagurdes LA, Mesulam MM, Gitelman DR, et al. Modulation of the spatial attention network by incentives in healthy aging and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2943–2948. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rademacher L, Krach S, Kohls G, et al. Dissociation of neural networks for anticipation and consumption of monetary and social rewards. Neuroimage. 2010;49:3276–3285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knutson B, Westdorp A, Kaiser E, et al. FMRI visualization of brain activity during a monetary incentive delay task. Neuroimage. 2000;12:20–27. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state” : A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manes F, Sahakian B, Clark L, et al. Decision-making processes following damage to the prefrontal cortex. Brain. 2002;125:624–639. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sturm VE, McCarthy ME, Yun I, et al. Mutual gaze in Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal and semantic dementia couples. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;6:359–367. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samanez-Larkin GR, Gibbs SE, Khanna K, et al. Anticipation of monetary gain but not loss in healthy older adults. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:787–791. doi: 10.1038/nn1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.