Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction (PVHI) is a major contributing factor to poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. We hypothesized that surviving infants with unilateral PVHI would have more favorable outcomes than those with bilateral PVHI.

METHODS

This was a multicenter, retrospective study of infants who were admitted to 3 NICUs in North Carolina from 1998 to 2004. The clinical course and late neuroimaging studies and neurodevelopmental outcomes of 69 infants who weighed <1500 g and had confirmed PVHI on early cranial ultrasonography were reviewed. A predictive model for Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition, Mental Developmental Index (MDI) <70 was constructed by using radiologic and clinical variables.

RESULTS

Infants with unilateral PVHI had higher median MDI (82 vs 49) and Psychomotor Developmental Index (53 vs 49) than infants with bilateral PVHI. Infants with unilateral PVHI were less likely to have severe cerebral palsy (adjusted odds ratio: 0.15 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.05–0.45]) than infants with bilateral PVHI. Infants who had unilateral PVHI and developed periventricular leukomalacia and retinopathy of prematurity that required surgery had an increased probability of having MDI <70 compared with those without these complications (probability of MDI <70: 89% [95% CI: 0.64–1.00] vs 11% [95% CI: 0.01–0.28]).

CONCLUSIONS

Infants with unilateral PVHI had better motor and cognitive outcomes than infants with bilateral PVHI. By combining laterality of PVHI, periventricular leukomalacia, and retinopathy of prematurity it is possible to estimate the probability of having an MDI <70, which will assist clinicians when counseling families.

Keywords: ultrasonography, grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage, preterm infants, outcome

Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction (PVHI) refers to intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) that is associated with hemorrhagic necrosis in the periventricular white matter of preterm infants. It is a devastating complication of prematurity and is predictive of short-term and long-term adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.1–8 PVHI may occur along with a wide range of brain injuries that are specific to preterm infants, including grades of IVH, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL).9–11

Accurate prediction of the outcomes of infants with PVHI can be relevant to withdrawal of intensive care for critically ill neonates and to design of rehabilitative care.12 A small number of studies have suggested that neurodevelopmental outcomes are more favorable for infants with unilateral PVHI compared with infants with bilateral PVHI. Those studies were limited by small sample size and variability in type and timing of neuroimaging and follow-up13–20; therefore, we undertook a multicenter study of a large sample of preterm infants with PVHI to explore whether outcomes differ for infants with unilateral versus bilateral PVHI.

METHODS

Study Design

For this retrospective cohort study, the study population included 69 surviving infants who were cared for at 3 NICUs in North Carolina between January 1998 and December 2004. These centers were the University of North Carolina Hospital, Duke University Medical Center, and Brenner Children’s Hospital at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center. We identified infants in hospital databases who had a diagnosis of grade 4 IVH and a birth weight <1501 g. Exclusion criteria were congenital viral infections, major congenital heart malformations, genetic abnormalities, structural brain malformations, metabolic diseases, and admission to the NICU solely for ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt placement. A total of 151 infants with grade 4 IVH were in the database, representing 4.3% of all children born at <1500 g at the 3 centers.

Maternal information included sociodemographic factors (age and race), birth in a tertiary care center, duration of gestation, antenatal steroid therapy, mode of delivery, and complications of pregnancy (eg, abruption, chorioamnionitis). Gestational age was estimated by using the date of the mother’s last menstrual period and was confirmed by fetal ultrasonography and Ballard examination after birth.21 Chorioamnionitis was defined as clinical symptoms and maternal fever ≥38.5°C. Additional birth data included weight, head circumference, and Apgar score at 5 minutes. Neonatal morbidities included culture-proven sepsis or meningitis (at anytime during the hospital stay), chronic lung disease defined as oxygen dependence at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age, indomethacin exposure, dexamethasone use to treat chronic lung disease, hydrocortisone use (>12.5 mg/m2), vasopressor use before 7 days of age, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC; Bell stage IIA or above), and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) that required laser surgery.

The earliest (<14 days of age) cranial ultrasonographic (CUS) image that was interpreted by the initial reader as showing a grade 4 IVH was copied for repeat interpretation by a single pediatric radiologist who was blinded to the original report. This reader assigned a diagnosis on the basis of the criteria documented by Bassan et al.22 PVHI was defined as an echodense lesion in the periventricular white matter, associated with IVH. PVHI when bilateral was clearly asymmetric and larger on the side ipsilateral to the IVH. We excluded infants in whom the echodensities were typical of PVL alone. PVL was defined as bilateral, usually symmetric echodensities in the white matter dorsolateral to the lateral ventricles. In addition, we excluded cases of periventricular cysts present within the first days of life or infants in whom echodensities were transient. The last available imaging (CUS, computed tomography, or MRI) at ≥30 days of age was examined for the presence of PVL or porencephalic cyst by the corresponding pediatric radiologist at each center.

Outcomes

Survival rates and follow-up data were measured up to 36 months’ corrected age (chronological age minus weeks of prematurity). Measures of neurodevelopmental outcomes included the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition (BSID II), Mental Developmental Index (MDI) and Psychomotor Developmental Index (PDI) with recommended adaptations for visual and auditory impairments.23 BSID II scores after 12 months of age were collected, and the last recorded scores were used for each infant (18–36 months). Cerebral palsy (CP) was diagnosed after 2 years of age by neurologic examination in the neonatal follow-up or rehabilitation clinics. CP was defined as appearance in early life of a persistent but not unchanging disorder in tone, movement, and posture that was attributable to a nonprogressive disorder of the brain. Gross Motor Function Classification System score was assigned.24 Mild CP corresponded to a Gross Motor Function Scale score of 1 to 2, moderate CP corresponded to a score of 3, and severe CP corresponded to a score of 4 to 5. A pediatric ophthalmologist diagnosed vision defects in a hospital clinic. Vision impairment was defined as blindness or bilateral field of vision loss. Seizure disorder was defined as >2 seizures after the neonatal period, with evidence of epileptiform changes on electroencephalogram.

Statistical Analysis

To examine the unadjusted association of laterality of IVH with MDI and PDI (as continuous variables), we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Logistic regression models were used to determine whether laterality of IVH was associated with the binary outcomes of MDI <70 or PDI <70. A threshold of 70 was used because it represents 2 SDs below the mean and corresponds to significantly delayed development. Ordinal logistic regression, specifically the proportional odds model, was used to analyze CP severity. We summarized the association with laterality of IVH by reporting unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the 3 outcomes. In multivariable logistic regression models, all of the variables were considered as possible confounders or precision variables; variables were included in the final model when they were found to alter the association between the outcome and laterality of IVH or to improve the fit of the model. Gestational age (for MDI <70 and PDI <70) and vasopressor use (for CP) were included in the final adjusted models because their inclusion altered the OR estimate for the effect of laterality. Univariate logistic regression models were used to describe the unadjusted associations of sepsis, indomethacin use, hydrocortisone or dexamethasone use, porencephalic cyst formation, NEC, VP shunt placement, VP shunt infection, ROP and chronic lung disease with MDI or PDI <70, CP, vision impairment, and seizures.

Multivariable logistic regression was also used to determine the predicted probability that a newborn will have a low MDI (MDI <70 or −2 SD). Predictions were made by using 3 covariates that were available at progressing time points: (1) laterality of IVH; (2) laterality of IVH and PVL; and (3) laterality of IVH, PVL, and ROP in a main-effects models. CIs for the predicted probabilities were obtained by using the bias-correct and accelerated bootstrap procedure.25

RESULTS

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

We compared the antenatal and immediate postnatal characteristics of our group of infants with unilateral and bilateral PVHI (Table 1). We found no significant differences between the 2 groups in regard to referral center, race, maternal age, mode of delivery, placental abruption at birth, or antenatal steroid administration. Infants with bilateral PVHI had a lower gestational age at birth (24.6 vs 25.9 weeks; P = .005).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Unilateral PVHI (n = 52) |

Bilateral PVHI (n = 17) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Referral center, % (n) | .100a | ||

| A | 38 (20) | 47 (8) | |

| B | 54 (28) | 29 (5) | |

| C | 8 (4) | 24 (4) | |

| Race, % (n) | .600a | ||

| White | 45 (23) | 29 (5) | |

| Black | 41 (21) | 53 (9) | |

| Hispanic | 12 (6) | 12 (2) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| Maternal age, mean (SD), yr | 28.2 (6.8) | 27.9 (6.8) | .800b |

| Cesarean delivery, % (n) | 56 (29) | 65 (11) | .500a |

| Chorioamnionitis, % (n) | 27 (14) | 29 (5) | .800a |

| Abruption at birth, % (n) | 17 (9) | 12 (2) | .600a |

| Antenatal steroids given, % (n) | 60 (31) | 53 (9) | .600a |

| Born at level 1 or 2 hospital, % (n) | 29 (15) | 29 (5) | .999a |

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wk | 25.9 (1.6) | 24.6 (1.3) | .005b |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 858 (215) | 743 (200) | .060b |

| Head circumference, mean (SD), cm | 24.0 (2.1) | 23.0 (2.9) | .070b |

| Female, % (n) | 38 (20) | 35 (6) | .800a |

| Apgar at 5 min, median (IQR) | 6 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | .300b |

| Vasopressor use, % (n) | 70 (35) | 65 (11) | .700a |

| Hydrocortisone use % (n) | 37 (19) | 24 (4) | .300a |

Pearson test.

Wilcoxon test.

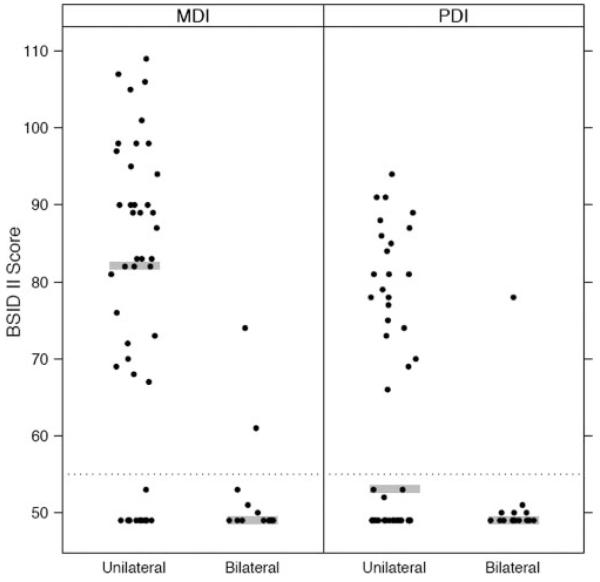

PVHI and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

Neurodevelopmental outcome differed in infants with unilateral versus bilateral PVHI (Table 2). Figure 1 demonstrates the associations between median MDI and PDI and laterality of PVHI. Infants with unilateral PVHI had a higher median MDI compared with infants with bilateral PVHI (82 [interquartile range (IQR): 29–90] vs 49 [IQR: 49–50]). The infants with bilateral PVHI were homogeneous. Most infants had the lowest possible MDI and PDI scores allowed by the test; however, 2 distinct groups of infants had unilateral PVHI: 1 group had an MDI <55 (3 SD), and the other had MDIs within 2 SD of the mean (Fig 1).

TABLE 2.

Association of PVHI With Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

| Parameter | n | Unilateral PVHI (n = 52) |

Bilateral PVHI (n = 17) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP, % (n) | 69 | 67 (35) | 88 (15) | .090a |

| CP severity, % (n) | 69 | <.001a | ||

| None or mild | 63 (33) | 12 (2) | ||

| Moderate or severe | 37 (19) | 88 (15) | ||

| MDI, median (IQR) | 62 | 82 (49–90) | 49 (49–50) | <.001b |

| MDI >70, %(n) | 62 | 64 (30) | 7 (1) | <.001a |

| PDI, median (IQR) | 61 | 53 (49–80) | 49 (49–50) | .020b |

| PDI >70, % (n) | 61 | 43 (20) | 7 (1) | .009a |

| Vision impairment, % (n) | 68 | 17 (9) | 31 (5) | .200a |

| Seizure disorder, % (n) | 69 | 13 (7) | 29 (5) | .100a |

Pearson test.

Wilcoxon test.

FIGURE 1.

Association between BSID II scores and laterality of PVHI. Shaded line represents the median. Dotted line represents a score of 55. Standardized means for the BSID II are 100.

We found that laterality of IVH was associated with both MDI <70 and PDI <70 (Table 3). In unadjusted models, bilateral PVHI was associated with a 25-fold increase in the odds of having an MDI <70. Bilateral PVHI was also associated with an 11-fold increase in the odds of PDI <70. We considered multivariable models in which all of the variables in Table 1 were potential cofounders or precision variables. After adjustment for gestational age, the ORs were not substantially different.

TABLE 3.

Bilateral Versus Unilateral PVHI and Risk for Poor Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

| Outcome | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| MDI <70 | 24.7 (3.0–204.6) | 21.0 (2.5–177.3)a |

| PDI <70 | 10.7 (1.3–88.9) | 9.4 (1.1–79.9)a |

| CP severity | 5.3 (1.9–15.3) | 6.8 (2.3–20.3)b |

ORs and 95% CIs were determined by using logistic regression. CP severity was expressed as odds of having moderate or severe CP versus mild CP or none.

Adjusted for gestational age.

Adjusted for vasopressor use.

In unadjusted models, bilateral PVHI was associated with a fivefold increase in the odds of more severe CP compared with infants with unilateral PVHI. After controlling for vasopressor use, infants with bilateral PVHI had a sevenfold increase in the odds of having more severe CP. Whereas 64% of infants with unilateral PVHI had no CP or mild CP (Table 4), 12% of infants with bilateral PVHI had no CP or mild CP. The predominant form of CP in infants with unilateral PVHI was hemiplegia; infants with bilateral PVHI more often exhibited diplegia or quadriplegia.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of CP in Infants With PVHI

| Characteristic | Unilateral PVHI (n = 52) |

Bilateral PVHI (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|

| CP severity, % (n) | ||

| None | 33 (17) | 12 (2) |

| Mild CP | 31 (16) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate CP | 17 (9) | 41 (7) |

| Severe CP | 19 (10) | 47 (8) |

| CP type, % (n) | ||

| None | 33 (17) | 12 (2) |

| Hemiplegia | 29 (15) | 18 (3) |

| Diplegia | 23 (12) | 41 (7) |

| Quadriplegia | 12 (6) | 24 (4) |

| Othera | 4 (2) | 6 (1) |

Gross Motor Function Classification System score of 5 with global hypotonia or athetoid type CP.

Association of Perinatal Variables With Outcomes in Infants With Unilateral PVHI

We examined variables that previously have been reported in the literature as being associated with various neurodevelopmental outcomes to determine their importance in the outcomes of our cohort with unilateral PVHI, in an attempt to differentiate between the 2 groups shown in Fig 1. The incidence of these variables in our group of infants is reported in Table 5. Median MDI and MDI <70 were not associated with sepsis, indomethacin use, patent ductus arteriosus ligation, NEC, dexamethasone use, shunt placement, or chronic lung disease. The same was true of median PDI and PDI <70. There was a strong association between ROP that required laser surgery and a lower median MDI (58 [IQR: 49–76] vs 83 [IQR: 73–96] in the nonlaser group; P = .006); therefore, a larger proportion of infants who had ROP that required surgery had an MDI <70 compared with those who did not require laser surgery (62% vs 23%; P = .007). In contrast, ROP that required laser surgery was not associated with worse motor outcomes such as CP or low PDI in infants with unilateral PVHI.

TABLE 5.

Perinatal Characteristics of Infants With PVHI

| Parameter, % (n) | Unilateral PVHI (n = 52) |

Bilateral PVHI (n = 17) |

Pearson Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin use | 53 (27) | 59 (10) | .70 |

| PDA ligation | 25 (13) | 29 (5) | .70 |

| Culture proven sepsis | 56 (29) | 59 (10) | .80 |

| NEC | 25 (13) | 47 (8) | .09 |

| Dexamethasone use | 25 (13) | 35 (6) | .40 |

| VP shunt placement | 37 (19) | 65 (11) | .04 |

| Shunt infection | 19 (10) | 24 (4) | .70 |

| ROP requiring surgery | 38 (20) | 53 (9) | .30 |

PDA indicates patent ductus arteriosus.

There was an association between NEC and moderate to severe CP (62% for infants with NEC vs 28% for infants without NEC; P = .03). Infants with VP shunts and unilateral PVHI had more moderate or severe CP (58% vs 24% in those without shunts; P = .02).

Vision impairment was associated with ROP, VP shunts, and VP shunt infections. Specifically, 6% of infants without VP shunt developed vision impairment versus 37% of those with a shunt (P = .005). When VP shunt infection was present in infants with unilateral PVHI, 60% also developed vision impairments versus 7% in the noninfected group (P < .001). ROP that required surgery was associated with vision impairment (30% vs 9% in group without ROP; P = .05). Seizure disorder was present only among infants with VP shunts (37% vs 0% in the group without a VP shunt; P < .001). Seizure disorder was more frequent in infants with ROP that required laser surgery (30% vs 3%; P = .006).

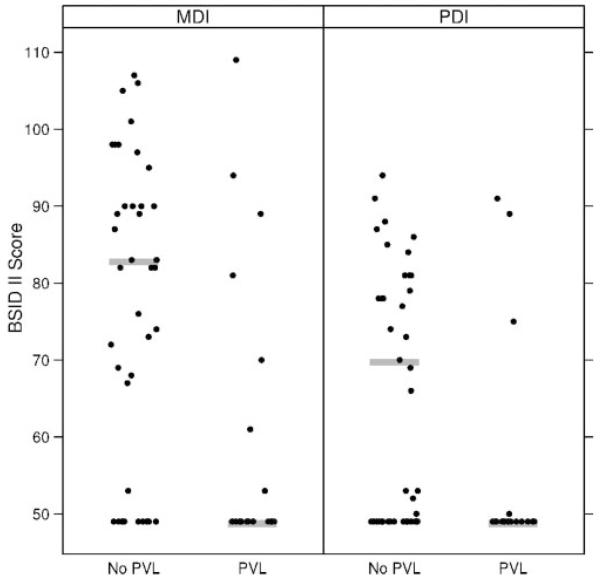

Association of Late CUS Findings With BSID II Scores in Infants With Unilateral PVHI

The outcomes of infants with bilateral PVHI were uniformly poor, regardless of whether they had PVL. In infants with unilateral PVHI, PVL was associated with lower MDI scores (83 vs 49; P = .004) and with a larger proportion of infants with a MDI <70 (64% vs 24%; P = .009). This association between PVL and neurodevelopmental assessment also held true for the PDI, with infants with PVL having lower median scores (49 vs 70; P = .04; Fig 2). Infants with unilateral PVHI and PVL had higher rates of vision impairment (41% vs 6%; P = .002) and were more likely also to have a seizure disorder (29% vs 6%; P = .01); however, 78% of infants with PVL had moderate to severe CP versus 18% in the group without PVL. There were no significant associations between specific neurodevelopmental outcomes and the presence of a porencephalic cyst in infants with unilateral PVHI.

FIGURE 2.

Association between BSID II scores and PVL in infants with unilateral PVHI. Shaded line represents the median. Standardized means for the BSID II are 100.

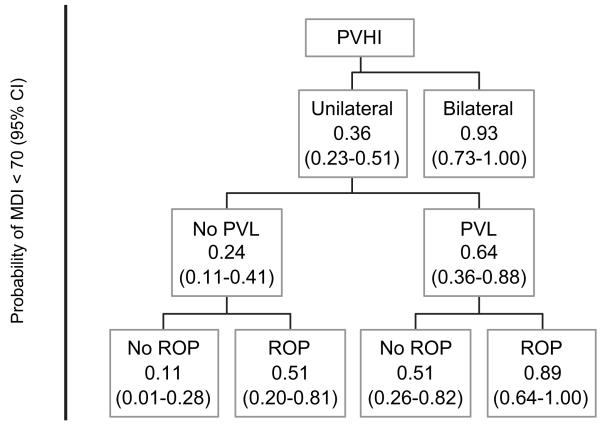

Cognitive Outcome Prediction Model in Infants With PVHI

Among infants with PVHI, laterality of PVHI, ROP that required laser surgery, and PVL were significant predictors of MDI status. Infants with bilateral PVHI had 93% probability of an MDI <70 compared with only 36% for infants with unilateral PVHI. Among infants with unilateral PVHI, the probability of an MDI <70 was 24% when the infant did not have PVL and was 64% when the infant did. Finally, for infants without PVL, presence of ROP that required surgery was associated with an increased probability of having an MDI <70. This can be seen in the predictive flowchart for MDI <70 (Fig 3).

FIGURE 3.

Prediction of MDI in infants with PVHI.

DISCUSSION

This is the largest study to date for which the primary goal was the comparison of outcomes in unilateral versus bilateral PVHI. The results support the hypothesis that cognitive and motor neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants with unilateral PVHI are more favorable than those of infants with bilateral PVHI. Infants with unilateral lesions have median cognitive scores that approach the mean for the general population. Two thirds of infants with unilateral PVHI have CP, but in a majority of these infants, CP is mild. Conversely, almost all infants with bilateral PVHI have very poor cognitive and motor outcomes. A combination of early CUS findings, late neuroimaging, and clinical course may help to predict more accurately the cognitive outcome of infants with unilateral PVHI.

In a previous study of 109 infants with PVHI, 67% had unilateral lesions but only 22 infants had neurodevelopmental outcome evaluations. They were assessed at varying ages with different standardized tests. The authors found that 6 of the 8 infants with localized unilateral PVHI had normal cognitive function (using various assessments) as compared with 2 of 6 in the bilateral group.14 Two other studies suggested that relatively few infants with unilateral PVHI have severe cognitive sequelae.17,26

We have identified 2 distinct groups of infants with unilateral PVHI: one with cognitive indices that approached average scores, and the other with profound delays. In a study of intraparenchymal echodensities and echolucencies, the Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborns (ELGAN) study group showed that ultrasonographic findings alone might not be sufficient to predict cognitive outcome, although they are very good at predicting motor outcome.27 This may be attributable to differences in the development of sensory and motor tracks compared with the development of cortical organization. The inherent predictive value of CUS may not be the issue but rather the imprecise characterization of severe IVH.

To differentiate between the 2 groups of infants with unilateral PVHI in our study, we designed a predictive algorithm that was based on recent studies showing that clinical data models may be more accurate than standard classification of CUS for predicting outcomes.28 We found that the presence of PVL and ROP that required laser therapy greatly increased the risk for poor cognitive outcome. A single radiologic classification scheme has yet to offer a generalizable predictive model. Studies that describe standardized and detailed classification of intraparenchymal hemorrhages may offer more precise information for prognosis.22,29

Not surprising, preterm infants with unilateral cortical lesions had better motor outcomes in our study than did those with bilateral lesions. Studies of brain function after hemispherectomy in older children and animal models suggested tremendous motor plasticity of the cortex.30,31 They also confirmed that complex bilateral activities can be reestablished after 1 side of the cortex is removed. This is attributable to greater adaptive plasticity in a neonate than in a young child or an adult.32 The reorganization of cortical circuits mediated by enhanced synaptic plasticity and pruning of synapses during early childhood may account for motor and cognitive remodeling.33,34 For example, after unilateral brain injury, lateralization of speech to the contralateral hemisphere follows hand function lateralization as a result of neuronal injury.35 In our study of infants with unilateral PVHI, many of these processes could account for some of the unexpected favorable outcomes.

The results of this study provide information that will benefit parents and clinicians during early decision-making for infants with PVHI. Consistent with other studies, our findings suggest that the neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants are not uniformly grim, even when severe intracranial injury has occurred.36 Conversely, children with bilateral intraparenchymal injury almost always develop severe impairments. Our results may be helpful in the early neonatal course, when parents must consider difficult decisions about the direction of clinical care. The results of our study will also be helpful at discharge from the nursery, when physicians must prepare a family for the challenges of potential neurodevelopmental disability. The knowledge that a majority of infants with PVHI will develop some form of CP may help parents advocate for early and aggressive intervention services. The milder forms of CP and the frequency of hemiplegia should motivate providers to take advantage of the first 3 years of life, when neural plasticity can be optimized.37 Our algorithm for cognitive outcome prediction can also be used to advocate for early developmental intervention services, including cognitive therapy.

This study has several limitations. Because of its retrospective nature, some of the outcomes data were incomplete and socioeconomic data were missing, precluding the analysis of the effect of maternal education on outcomes. The late imaging studies were in differing modalities because of varying practices at the 3 participating centers. There were, however, several advantages to including multiple centers in the same region of the state, including the uniformity of early intervention and therapeutic services and of patient populations with similar demographic characteristics. Although we had a single pediatric radiologist confirm the presence of PVHI on early CUS, other studies have shown that it is not necessary to discount the original CUS reading by a local pediatric radiologist.38,39

The implications of this study for neurodevelopmental predictive models of infants with severe brain lesions are twofold. The detailed classification of early brain injury in preterm infants studied in a prospective manner in a large population would be valuable. Additional description of both unilateral and bilateral PVHI would likely help to differentiate and predict outcomes. This would be meaningful in combination with an equally detailed late imaging study such as MRI, involving classification systems for PVL and other forms of white matter injury.4,40 Algorithms that combine both neuroimaging and clinical variables could then be developed to predict outcomes of high-risk infants in the same way that this has been accomplished for prenatal variables.41 Finally, given the potential for plasticity of the premature brain in the face of parenchymal lesions, there is a pressing need to design and evaluate therapeutic modalities to rehabilitate preterm infants with severe white matter injury.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT

The neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants with PVHI have been reported as very poor, influencing decision-making in the NICU. No large studies have differentiated between the outcomes of infants with unilateral versus bilateral PVHI.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Preterm infants with unilateral PVHI have better neurodevelopmental outcomes than previously thought. A combination of radiographic and clinical characteristics can help predict the cognitive outcomes of these infants.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PVHI

periventricular hemorrhagic infarction

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- PVL

periventricular leukomalacia

- VP

ventriculoperitoneal

- NEC

necrotizing enterocolitis

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

- CUS

cranial ultrasound

- BSID II

Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition

- MDI

Mental Developmental Index

- PDI

Psychomotor Developmental Index

- CP

cerebral palsy

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- IQR

interquartile range

REFERENCES

- 1.Hack M, Fanaroff AA. Outcomes of children of extremely low birthweight and gestational age in the 1990s. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5(2):89–106. doi: 10.1053/siny.1999.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hack M, Taylor HG. Perinatal brain injury in preterm infants and later neurobehavioral function. JAMA. 2000;284(15):1973–1974. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.15.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson P, Doyle LW. Neurobehavioral outcomes of school-age children born extremely low birth weight or very preterm in the 1990s. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3264–3272. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamrick SE, Miller SP, Leonard C, et al. Trends in severe brain injury and neurodevelopmental outcome in premature newborn infants: the role of cystic periventricular leukomalacia. J Pediatr. 2004;145(5):593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laptook AR, O’Shea TM, Shankaran S, Bhaskar B, NICHD Neonatal Network Adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely low birth weight infants with a normal head ultrasound: prevalence and antecedents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):673–680. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis M, Bendersky M. Cognitive and motor differences among low birth weight infants: impact of intraventricular hemorrhage, medical risk, and social class. Pediatrics. 1989;83(2):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherlock RL, Synnes AR, Grunau RE, et al. Long-term outcome after neonatal intraparenchymal echodensities with porencephaly. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(2):F127–F131. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.110726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larroque B, Marret S, Ancel PY, et al. White matter damage and intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm infants: the EPIPAGE study. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):477–483. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levene MI, Chervenak FA, Whittle MJ. Fetal and Neonatal Neurology and Neurosurgery. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; London, England: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volpe JJ. Neurology of the newborn. Major Probl Clin Pediatr. 1981;22:1–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson DK, Goldworth A. Ethical considerations in neuroimaging and its impact on decision-making for neonates. Brain Cogn. 2002;50(3):449–454. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(02)00523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cioni G, Bos AF, Einspieler C, et al. Early neurological signs in preterm infants with unilateral intraparenchymal echodensity. Neuropediatrics. 2000;31(5):240–251. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzzetta F, Shackelford GD, Volpe S, Perlman JM, Volpe JJ. Periventricular intraparenchymal echodensities in the premature newborn: critical determinant of neurologic outcome. Pediatrics. 1986;78(6):995–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMenamin JB, Shackelford GD, Volpe JJ. Outcome of neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage with periventricular echodense lesions. Ann Neurol. 1984;15(3):285–290. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackman JA, McGuinness GA, Bale JF, Jr, Smith WL., Jr. Large postnatally acquired porencephalic cysts: unexpected developmental outcomes. J Child Neurol. 1991;6(1):58–64. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vries LS, Rademaker KJ, Groenendaal F, et al. Correlation between neonatal cranial ultrasound, MRI in infancy and neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with a large intraventricular haemorrhage with or without unilateral parenchymal involvement. Neuropediatrics. 1998;29(4):180–188. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Vries LS, Roelants-van Rijn AM, Rademaker KJ, Van Haastert IC, Beek FJ, Groenendaal F. Unilateral parenchymal haemorrhagic infarction in the preterm infant. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5(4):139–149. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2001.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rademaker KJ, Groenendaal F, Jansen GH, Eken P, de Vries LS. Unilateral haemorrhagic parenchymal lesions in the preterm infant: shape, site and prognosis. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(6):602–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eken P, de Vries LS, van der Graaf Y, Meiners LC, van Nieuwenhuizen O. Haemorrhagic-ischaemic lesions of the neonatal brain: correlation between cerebral visual impairment, neurodevelopmental outcome and MRI in infancy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1995;37(1):41–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1995.tb11931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasidharan K, Dutta S, Narang A. Validity of New Ballard Score until 7th day of postnatal life in moderately preterm neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(1):F39–F44. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.122564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassan H, Limperopoulos C, Visconti K, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in survivors of periventricular hemorrhagic infarction. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):785–792. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd ed. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palisano RJ, Hanna SE, Rosenbaum PL, et al. Validation of a model of gross motor function for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 2000;80(10):974–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efron BA, Robert J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roelants-van Rijn AM, Groenendaal F, Beek FJ, Eken P, van Haastert IC, de Vries LS. Parenchymal brain injury in the preterm infant: comparison of cranial ultrasound, MRI and neurodevelopmental outcome. Neuropediatrics. 2001;32(2):80–89. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Shea TM, Kuban KC, Allred EN, et al. Neonatal cranial ultrasound lesions and developmental delays at 2 years of age among extremely low gestational age children. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0594. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/3/e662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broitman E, Ambalavanan N, Higgins RD, et al. Clinical data predict neurodevelopmental outcome better than head ultrasound in extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2007;151(5):500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassan H, Feldman HA, Limperopoulos C, et al. Periventricular hemorrhagic infarction: risk factors and neonatal outcome. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35(2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiricozzi F, Chieffo D, Battaglia D, et al. Developmental plasticity after right hemispherectomy in an epileptic adolescent with early brain injury. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21(11):960–969. doi: 10.1007/s00381-005-1148-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston MV. Clinical disorders of brain plasticity. Brain Dev. 2004;26(2):73–80. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(03)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staudt M. Reorganization of the developing human brain after early lesions. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(8):564. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wall JT, Xu J, Wang X. Human brain plasticity: an emerging view of the multiple substrates and mechanisms that cause cortical changes and related sensory dysfunctions after injuries of sensory inputs from the body. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39(2-3):181–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein DG, Hoffman SW. Concepts of CNS plasticity in the context of brain damage and repair. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003;18(4):317–341. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auer T, Pinter S, Kovacs N, et al. Does obstetric brachial plexus injury influence speech dominance? Ann Neurol. 2009;65(1):57–66. doi: 10.1002/ana.21538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen MC. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(2):123–128. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f88bb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taub E. Harnessing brain plasticity through behavioral techniques to produce new treatments in neurorehabilitation. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):692–704. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuban K, Adler I, Allred EN, et al. Observer variability assessing US scans of the preterm brain: the ELGAN study. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(12):1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hintz SR, Slovis T, Bulas D, et al. Interobserver reliability and accuracy of cranial ultrasound scanning interpretation in premature infants. J Pediatr. 2007;150(6):592–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inder TE, Warfield SK, Wang H, Huppi PS, Volpe JJ. Abnormal cerebral structure is present at term in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):286–294. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, Green C, Higgins RD. Intensive care for extreme prematurity: moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1672–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]