Abstract

Toxocarosis is one of the most prevalent human helminthosis caused by larvae of Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati, the most widely distributed nematode parasites of dogs and cats respectively. Soil is considered as the principal source of transmission of Toxocara infection to human beings. With increasing population of dogs and cats, soil contamination with ova or eggs of Toxocara can be detected in public and private locations of city backyards, playgrounds, streets, sand pits and so on, regardless of the season of the year. In this context the present study was carried out to estimate the extent of soil contamination with Toxocara eggs in public parks, playgrounds and few kennels situated in different parts of Chennai city. A total of 105 soil samples from 40 public places and 5 kennels were screened for the presence of parasitic eggs. Toxocara eggs were recovered from 5 soil samples indicating an overall prevalence rate of 4.75 %. Out of 80 samples collected from public places, three samples, one each from Mogappair, My lady park (Periamet) and Madras Veterinary College showed the presence of Toxocara spp. eggs indicating an overall prevalence of 3.75 per cent. Out of the 25 samples from 5 kennels, two samples one each from Tambaram and Thorappakkam kennels were positive for Toxocara eggs with prevalence of 8 per cent. Low prevalence of Toxocara eggs in soil samples of these areas can be attributed to the less population of pups, the carriers of adult worms and the active source of soil contamination. The progress made in ABC (animal birth control) programme carried out by both governmental and non-governmental organizations has contributed to reduction of birth rate in dogs and thereby reduced the chances of soil contamination with Toxocara eggs to a certain extent in Chennai city.

Keywords: Toxocara ova, Soil contamination, ABC programme, Chennai

Introduction

Toxocara larva migrans or Human Toxocarosis is a helminthic zoonosis caused by larval stages of Toxocara canis and less frequently by Toxocara cati, the adult stages of which are found in the canid and felid intestines respectively. It poses a serious human health problem in temperate and tropical climates. Toxocarosis results in a wide variety of syndromes in humans, which include visceral larva migrans, ocular larva migrans, Covert Toxocarosis, Common Toxocarosis and Cerebral Toxocarosis, although most infections are probably subclinical (Holland and Smith 2006).

The most widely recognized source of human infection is ingestion of embryonated eggs through contaminated soil and this occurs most frequently in toddlers. Eggs are found in soil of public/private places such as playgrounds, parks, beaches, gardens and backyards. The long term survival of Toxocara spp. outside their hosts coupled with high reproduction status, is responsible for significant contamination of soil with infective eggs. With increasing population of dogs and cats, soil contamination with eggs of Toxocara are detected in public and private locations of city backyards, playgrounds, streets, sand pits etc., regardless of the season of the year from various parts of the world (Gawor et al. 2008; Jarosz et al. 2010). The existence of viable Toxocara eggs in superficial layers of sand presents a potential public health hazard. For this reason more studies have been carried out in recent years to determine the prevalence of Toxocara eggs in the soil of parks and especially in the sands in children’s playground in different parts of the world.

Chennai is located at 13.04°N and 80.17°E on the southeast coast of India and in the northeast corner of Tamil Nadu. Chennai features a tropical wet and dry climate. For most of the year, the weather is hot and humid. The hottest part of the year is late May and early June. The average annual rainfall is about 1,400 mm (55 in). Chennai city is having a dog population of about one lakh of which the stray dog population comes around 30.000. These dogs are freely in the environment and produce offsprings which may contaminate the environment with Toxocara ova. Soil contamination with Toxocara ova is reported worldwide (Holland and Smith 2006). However public health impact and soil contamination of Toxocara ova has been sporadically reported from India (Das et al. 2009).To fill up the lacunae, the present study was envisaged to study the soil contamination with Toxocara ova in various places of Chennai city.

Materials and methods

The soil samples were collected randomly from 40 public places and five kennels situated in various part of Chennai. Two sets of soil samples were collected from public places like parks, playgrounds etc. and kennels. About 50 g of soil sample from 5 cm deep layer was taken from each area into plastic containers and brought to the laboratory (Coelho et al. 2001).

The soil samples were processed for recovering the ova by the method of Dunsmore et al. (1984) as described by Mondarino-Pereira et al. (Mandarino-Pereira et al. 2010) with modifications. 30 g of soil sample was taken in a 50 ml centrifuge tube and soaked overnight in tap water with three drops of Tween 80. The contents were mixed thoroughly in the tube for ten minutes. Two centrifuge tubes of 15 ml were filled with the mixture and centrifuged for 10 min at 2,000 rpm. The supernatant was discarded and Sodium Nitrate solution (NaNO3) (d = 1.20) was added until half of the tube and the sediment was suspended. The tubes were topped with NaNO3 and allowed to stand for 25 min. Later a coverslip was touched on the meniscus and placed on a microscopic slide and observed under 10X of compound microscope.

Results

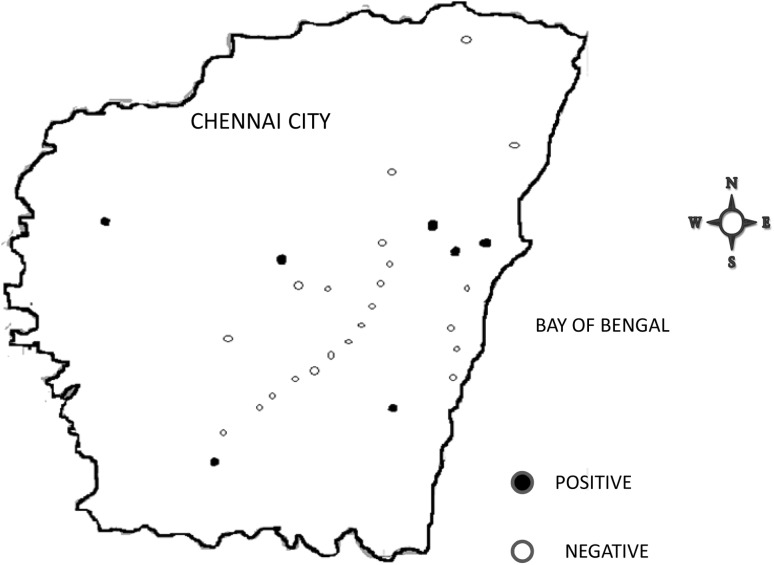

Toxocara eggs were recovered from 5 of 105 soil samples collected from 40 public places and 5 kennels indicating an overall prevalence rate of 4.75 %. Out of 80 samples collected from public places, three samples, one each from Mogappair, My lady park (Periamet) and Madras Veterinary College showed the presence of Toxocara spp. eggs indicating an overall prevalence of 3.75 per cent (Table 1). Among 25 soil samples collected from five kennels, two samples from private kennels of Tambaram and Thorappakkam showed presence of Toxocara spp. eggs with a prevalence rate of 8 per cent (Table 2). Based on the morphology, these eggs belonged to T. canis. The soil samples positive for Toxocara eggs, collected from various places of Chennai were mapped (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Toxocara ova in public places of Chennai

| S.No. | Places | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Mogappair, My Lady Park and Madras Veterinary College campus | Positive |

| 2. | Aminjikarai, Chindradipet, Periamet, Secrateriat, Choolai, Choolaimedu, Nehru Stadium, Nungambakkam, Semmozhi Poonga, Porur, Kattuppakkam, Adayar, Egmore, Arumbakkam, Marina Beach, Besant Nagar Beach, Madhavaram, Thiruvotriyur, Pallavakkam, Pattabhiram, Chitlappakkam, Tambaram, Pulianthope, Minjur, Kilpauk, Chetput, Minambakkam, Kodambakkam, Mambalam, Saidapet, Guindy Park, St.Thomas Mount, Thrisulam, Chrompet, Velachery, Mylapore and Purasawalkam | Negative |

Table 2.

Prevalence of Toxocara ova in kennels of Chennai

| S.No. | Kennels | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Blue cross of India, Velachery, Thiruvotriyur and PFA, Choolai | Negative |

| 2. | Thoraippakkam and Tambaram | Positive |

Fig. 1.

Mapping of soil contamination of Toxocara ova in Chennai city, India

Discussion

The frequency of Toxocara eggs in soil samples from public places of Chennai city was found to be low. The prevalence rate of Toxocara ova soil contamination of 0–100 per cent has been reported from different parts of the world (Table 3). The sample size for various prevalence studies of Toxocara ova was from 6 to 816 (Habluetzal et al. Habluetzel et al. 2003; Das et al. 2009). The highest rate of prevalence of Toxocara ova contamination was reported from countries like Japan, Germany, Nigeria, Brazil and Mexico (Uga 1993; Duwel 1984; Maikai et al. 2008; Coelho et al. 2001; Gracia et al. 2007). The less prevalence rate of 4.75 per cent in this study can be attributed to less number of soil samples screened from each place and also less quantity of soil samples (30 g) utilized for the study. It has been suggested that large amount of soil should be examined to determine the frequency of Toxocara ova in ground accurately (Duwel 1984). The change in the environmental conditions over these periods of time can also be a reason for the less prevalence rate as many environmental factors determine the sustainability of Toxocara eggs in the environment (Dunsmore et al. 1984). However lowest prevalent rate of Toxocara ova contamination was reported in countries like Australia, India, Spain, Canada etc. (Franzco et al. 2003; Das et al. 2009; Ruiz de Ybanez et al. 2001; Gualazzi et al. 1986).

Table 3.

The prevalence of Toxocara ova from different places of world (1980–2011)

| Places | No. of samples | Prevalence (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey, USA | 629 | 0.4 | Surgan et al. 1980 |

| Maryland, USA | 146 | 11 | Childs 1985 |

| Michigan, USA | 114 | 22 | Ludlam and Platt 1989 |

| CT, USA | 319 | 14.40 | Chorazy and Richardson 2005 |

| Michigan, USA | 114 | 22 | Karen et al. 1989 |

| London, UK | 503 | 66 | Snow et al. 1987 |

| London, UK | 521 | 6.3 | Gillespie et al. 1991 |

| NS, Canada | 567 | 2.30 | Gualazzi et al. 1986 |

| Victoria, Australia | 180 | 0.55 | Franzco et al. 2003 |

| Melbourne, Australia | 108 | 1 | Carden et al. 2003 |

| Perth, Australia | 66 | 0 | Dunsmore et al. 1984 |

| Utrecht, Netherlands | 108 | 7 | Jansen et al. 1993 |

| Dublin, Ireland | 53 | 6 | Holland et al. 1991 |

| Dublin, Ireland | 228 | 15 | O’Lorcain 1994 |

| Havana city, Cuba | 45 | 42.2 | Dumenigo and Galvez. 1995 |

| Mexico city, Mexico | 145 | 12.5 | Vasquez et al. 1996 |

| Mexicali, Mexico | 32 | 62.5 | Gracia et al. 2007 |

| Heliopolis, Egypt | 600 | 30.3 | Oteifa and Moustafa 1997 |

| Songkhla, Thailand | 102 | 19 | Uga et al. 1997 |

| Malaysia | 44 | 45.5 | Loh and Israf 1998 |

| Kualalumpur, Malaysia | 89 | 1 | Uga et al. 1996 |

| Surabaya, Indonesia | 223 | 17 | Uga et al. 1995 |

| Madrid, Spain | 175 | 9.71 | Angulo et al. 1987 |

| Salamanca, Spain | 263 | 6.6 | Simon and Conde 1987 |

| Salamanca, Spain | 698 | 4.5 | Conde et al. 1989 |

| Murcia, Spain | 644 | 1.24 | Ruiz de Ybanez et al. 2001 |

| Argentina | 475 | 2.80 | Alonso et al. 2001 |

| Amman, Jordan | 226 | 15.48 | Abo Shehada 1989 |

| Minas Gerais, Brazil | 23 | 17.40 | Guimaraes et al. 2005 |

| Sorocaba, Brazil | 30 | 53.0 | Coelho et al. 2001 |

| Cambo Grande, Brazil | 74 | 20 | de Araujo et al. 1999 |

| Saopolo, Brazil | 120 | 17.5 | Santarem et al. 1998 |

| Saopolo, Brazil | Queiroz et al. 2006 | ||

| Saopolo, Brazil | 31 | 29 | Santarém et al. 2008 |

| Aracatuba, Brazil | 535 | 0 | Nunes et al. 2000 |

| Seropedica, Brazil | 25 | 8 | Mandarino-Pereira et al. 2010 |

| Prague, Czechoslovakia | 200 | 24 | Valkounova 1982 |

| Frankfurt, Germany | 562 | 87.10 | Duwel 1984 |

| Warnemunde, Germany | 126 | 2 | Schottler 1997 |

| Tokushima, Japan | 46 | 63.30 | Shimizu 1993 |

| Osaka, Japan | 40 | 75 | Abe and Yasukawa 1997 |

| Hyogo Prefecture, Japan | 13 | 100 | Uga 1993 |

| Sapparo, Japan | 107 | 8.41 | Matsuo and Nakashio 2005 |

| Basrah, Iraq | 180 | 12.20 | Mahdi and Ali 1993 |

| Konya, Turkey | 48 | 4.16 | Guclu and Aydenizoz 1998 |

| Ankara, Turkey | 170 | 30.60 | Oge and Oge 2000 |

| Istanbul, Turkey | 132 | 8.33 | Toparlak et al. 2002 |

| Elazir, Turkey | 744 | 3.22 | Kaplan et al. 2002 |

| Van, Turkey | 107 | 25.97 | Ayaz et al. 2003 |

| Aydin, Turkey | 111 | 18.91 | Gurel et al. 2005 |

| Kirikkale, Turkey | 480 | 15.60 | Aydenizoz Ozkayhan 2006 |

| Ankara, Turkey | 259 | 15.05 | Avcioglu and Burgu 2008 |

| Erzurum, Turkey | 214 | 64.28 | Avcioglu and Balkaya 2011 |

| Poznani, Poland | 534 | 10 | Mizgajska 1997 |

| Krakow, Poland | 160 | 23 | Mizgajska 2000 |

| Poznani, Poland | 112 | 6.3 | Masnik 2000 |

| Elblag, Poland | 72 | 14 | Jarosz 2001 |

| Gdansk, Poland | 162 | 13 | Rokicki et al. 2007 |

| Wroclaw, Poland | 100 | 6 | Mizgajska 1999 |

| Kolaczkowo, Poland | 200 | 14.5 | Jarosz et al. 2010 |

| Ancona, Italy | 22 | 14 | Giacometti et al. 2000 |

| Marche Region, Italy | 6 | 50 | Habluetzel et al. 2003 |

| Kathmandu, Nepal | 122 | 23 | Rai et al. 2000 |

| BuenosAires, Argentina | 242 | 13.2 | Fonrouge et al. 2000 |

| Shiraz, Iran | 112 | 6.3 | Motazedian et al. 2006 |

| Santiago, Chile | 288 | 13.5 | Castillo et al. 2000 |

| Bogota, Columbia | 376 | 5.8 | Polo Terán et al. 2007 |

| Eastern Nigeria | 400 | 42.5 | Chiejna and Ekwe 1986 |

| Kaduna, Nigeria | 608 | 50.4 | Maikai et al. 2008 |

| Madras, India | 527 | 18.41 | Gunaseelan et al. 1985 |

| Calcutta, India | 450 | 7.25 | Biswas et al. 1986 |

| Punjab, India | 208 | 19.71 | Singh et al. 1997 |

| Andhra Pradesh, India | 168 | 6.5 | Kumar and Hafeez 1998 |

| Chandigarh, India | 120 | 4.16 | Grover et al. 2000 |

| Bangalore, India | 208 | 23 | D’Souza et al. 2002 |

| Assam, India | 130 | 6.12 | Singh et al. 2004 |

| Pondicherry, India | 816 | 2.21 | Das et al. 2009 |

| Chennai, India | 105 | 4.75 | Present study |

Toxocara eggs found in the positive samples were non embryonated contrary to the embryonated ova found in other studies (Ruiz de Ybanez et al. 2001). This may be due to the fact that the season in which sampling was performed corresponds to a hot and dry environmental condition avoiding the parasite development.

Along with this, the progress made in ABC (animal birth control) programme carried out by both governmental and non-governmental organizations contributed to reduction of birth rate in dogs and thereby reduced the chances of soil contamination to a certain extent with Toxocara eggs. This can also attribute to the low prevalence rate observed in this study when compared to the prevalence rate reported twenty seven years back by Gunaseelan et al. (1985). The reduction of Toxocara ova over a period of time was also reported from Poznani, Poland (Mizgajska 1997; Masnik 2000), Ankara, Turkey (Oge and Oge 2000; Avcioglu and Burgu 2008), London, UK (Snow et al. 1987; Gillespie et al. 1991), Salamanca, Spain (Simon and Conde 1987; Conde et al. 1989) and Saopolo, Brazil (Santarem et al. 1998; Queiroz et al. 2006).

During the study, it has been found that majority of the public places are frequented by dogs, but mainly adults. The absence of high prevalence of Toxocara eggs in these areas can be attributed to the fact that young pups are the carriers of the worms and the active source of soil contamination.

Out of twenty five samples collected from five kennels only two were positive. Even though the chances of getting Toxocara eggs are more in kennels with pups, the less prevalence rate in this study can be due to the maintenance conditions followed in kennels. In three kennels, the washings from the puppy shelters are directly connected to the common drainage and the floors are found to be concreted except in one kennel, and they follow regular treatment of floors with disinfectants and regular deworming of pups and adult dogs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Dean, Madras Veterinary College, Chennai-600007 for providing necessary facilities. The research was funded by Tamil Nadu state council for science and technology under the project Detection of public health impact of Toxocara ova in Chennai” (Code No. MS. 01).

References

- Abe N, Yasukawa A. Prevalence of Toxocara spp. eggs in sandpits of parks in Osaka city, Japan with notes on the prevention of eggs contamination by fence construction. J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59:79–80. doi: 10.1292/jvms.59.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abo Shehada MN. Prevalence of Toxocara ova in some school and public grounds in northern and central Jordan. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;83:73–75. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1989.11812313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stein M, Chamorro MC, Bojanich MV. Contamination of soils with eggs of Toxocara in subtropical city in Argentina. J Helminthol. 2001;75:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo R, Aguila C, Guillen JL. Contaminacion de suelos de parques publicos por Toxocara canis. Revista Iberica de Parasiyologia Boletin extraordinario. 1987;12:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Avcioglu H, Balkaya I. The relationship of public parks accessibility to dogs to the presence of Toxocara species ova in the soil. Vector borne zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:177–180. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avcioglu H, Burgu A. Seasonal prevalence of Toxocara ova in soil samples from public parks in Ankara, Turkey. Vector borne zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:345–350. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz E, Yaman M, Gul A. Prevalence of Toxocara spp. eggs in soil of public parks in Van, Turkey. Ind Vet J. 2003;80:574–576. [Google Scholar]

- Aydenizoz Ozkayhan M. Soil contamination with ascarid eggs in playgrounds in Kirikkale, Turkey. J Helminthol. 2006;80:15–18. doi: 10.1079/JOH2005311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas G, Bhattacharya AK, Sen GP. Dog a source of human visceral larva migrans. Indian J Public Health. 1986;30:22. [Google Scholar]

- Carden SM, Meusemann R, Walker J, Stawell RJ, Mac Kinnon JR, Smith D, Stawell AM, Hall AJ. Toxocara canis eggs presence in Melbourne parks and disease incidence in Victoria. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;31:143–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo D, Paradez C, Zanartu C, Castillo G, Mercado R, Munoz V, Schenone H. Environmental contamination with Toxocara spp. eggs in public squares and parks from Santiago, Chile. Bol Chil Parasitol. 2000;55:86–91. doi: 10.4067/S0365-94022000000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiejna SN, Ekwe TO. Canine toxocariosis and the associated environmental contamination of urban areas in eastern Nigeria. Vet Parasitol. 1986;22:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(86)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs JE. The prevalence of toxocara species ova in backyards and gardens of Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:1092–1094. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.75.9.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorazy ML, Richardson DJ. A survey of environmental contamination with ascarid ova in Willingford, Connecticut. Vector borne Zoon Dis. 2005;5:33–39. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2005.5.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho LMPS, Dini CY, Milman MHA, Oliveira SM. Toxocara spp. eggs in public squares of Soracaba, Sao Paulo state, Brazil. Rev Inst Med S Paulo. 2001;43:189–191. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652001000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde L, Muro A, Simon F. Epidemiological studies on toxocariasis and visceral larva migrans in a zone of western Spain. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;83:615–620. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1989.11812395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza PE, Dhanalakshmi H, Jagannath MS. Soil contamination with canine hookworm and roundworm ova in Bangalore. J Parasitic Dis. 2002;26:107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Das SS, Kumar D, Sreekrishnan R, Ganesan R. Soil contamination of public places, play ground and residential area with ova of Toxocara. Indian J Vet Res. 2009;17(2):13–16. [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo FR, Crocci AJ, Rodrigues RG, Avalhaes J, Da S, Miyoshi MI, Salgado FP, da Silva MA, ML Pereira. Contamination of public squares of Campo Grande, Mato grosso do Sul, Brazil with eggs of Toxocara and Ancylostoma in dog feces. Revista Da sociedade Brasilieira de medicina Tropical. 1999;32:581–583. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86821999000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumenigo B, Galvez D. Soil contamination in Cuidad de La Habana province with Toxocara canis eggs. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 1995;47:178–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JD, Thompson RCA, Bates IA. Prevalence and survival of Toxocara canis eggs in the urban environment of Perth, Australia. Vet Parasitol. 1984;16:303–311. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(84)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duwel D. The prevalence of Toxocara eggs in the sands in children playgrounds in Frankfurt. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;78:633–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonrouge R, Guardis MV, Radman NE, Archelli SM. Contaminacion de suelos con huevos de Toxocara sp. En plazas y parques publicos de La Plata, Buenos Aires Argentina. Bol Chil Parasitol. 2000;155:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzco SMC, Franzco RM, Walker J et al,(2003) Toxocara canis egg presence in Melbourne parks and disease incidence in Victoria. Clin Exp Ophthal 31:143–146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gawor J, Borecka A, Żarnowska H, Marczynska M, Dobosz S. Environmental and personal risk factors for toxocariasis in children with diagnosed disease in urban and rural areas of central Poland. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Fortuna M, Osimani P, Antonicelli L, Del Prete MS, Riva A, D’Errico MM, Petrelli E, Scalise G. Environmental and serological evidence for the presence of toxocariasis in the urban area of Ancona, Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:1023–1026. doi: 10.1023/A:1010853124085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SH, Pereira M, Ramsay A. The prevalence of Toxocara canis ova in soil samples from parks and gardens in the London area. Public Health. 1991;105:335–339. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(05)80219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia LT, Serrano AB, Valencia GL, Sosa ART, Henry MR, Ramirez EQ. Frequency of Toxocara canis eggs in public parks of the urban area of Mexicali, B.C. Mexico J Ani Vet Adv. 2007;6:430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Grover R, Bhatti G, Aggarwal A, Malla N. Isolation of Toxocara eggs in and around Chandigarh, India. J Parastic Dis. 2000;24:57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gualazzi DA, Embil JA, Pereira LH. Prevalence of helminth ova in recreational areas of Peninsular Halifax, Nova Scotia. Can J Public Health. 1986;77:145–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guclu F, Aydenizoz M. Cocuk parklarindaki kumlarin kopek ve kedi helminthi yumurtalari ile kontaminasyonunun tesbiti. T parazitol Derg. 1998;23:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes AM, Alves EG, Rezende GF. Toxocara sp eggs and Ancylostoma sp. Larva in public parks. Brazil Revista de Saude Publica. 2005;39:293–295. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102005000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaseelan L, Ramdass P, Raghavan N. Epidemiological studies on Toxocara canis infection in children in Madras city. Cheiron. 1985;14:326. [Google Scholar]

- Gurel FS, Ertug S, Okyay P. Aydin il merkezindeki parklarda Toxocara spp yumurta gorulme sikliginin aras tirilmasi. T Parazitol Derg. 2005;29:177–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habluetzel A, Traldi G, Ruggieri S, Attili Ar, Scuppa P, Marchetti R, Menghini G, Esposito F. An estimation of Toxocara canis prevalence in dogs, environmental egg contamination and risk of human infection in Marche region of Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2003;2561:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CV, Smith HV. Toxocara: The enigmatic Parasite. USA: CABI Publishing Cambridge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holland CV, Connor P, Taylor MR, Hughes G, Girdwood RW, Smith H. Families, parks, gardens and toxocariasis Scandinavian. J Infect Dis. 1991;23:225–231. doi: 10.3109/00365549109023405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J, van Knapen F, Schreurs M, van Wijngaarden T. Toxocara ova in parks and sandboxes in the city of Utrecht. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd. 1993;118:611–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz W. Soil contamination with Toxocara spp. Eggs in Elblag area. Wiadomosci Parazytologiczne. 2001;47:143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz W, Mizgajska-Wiktor H, Kirwan Z, Konarsk J, Rychlick W, Wawrzyniak G. Developmental age, physical fitness and Toxocara seroprevalence amongst lower: secondary students living in rural areas contaminated with Toxocara eggs. Parasitology. 2010;137:53–63. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009990874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan K, Kuk S, Kalkan A (2002) Elazigdaki cocuk parklari ve oyun sahalarinda Toxocara spp. yumurta gorulme sikliginin arastirilmasi. Firat Uni Sag Bil Derg 16: 277–279

- Karen E, Ludlam BS, Platt TR. The relationship of park maintenance and accessibility to dogs to the presence of Toxocara spp. ova in the soil. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:633–634. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.79.5.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar BV, Hafeez M. A study on the prevalence of Toxocara spp. eggs at public places in Andhra Pradesh. J Commun Dis. 1998;30:197–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh AG, Israf DA. Tests on the centrifugal floatation technique and its use in estimating the prevalence of Toxocara in soil samples from urban and suburban areas of Malaysia. J Helminthol. 1998;72:39–42. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X0000095X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlam KE, Platt TR. The relationship of park maintenance and accessibility to dogs to the presence of Toxocara spp. ova in the soil. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:633–634. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.79.5.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi NK, Ali HA. Toxocara eggs in soil of public places and schools in Basrah, Iraq. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1993;87:201–205. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1993.11812755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maikai BV, Umoh JU, Ajanusi OJ, Ajogi I. Public health implications of soil contaminated with helminth eggs in the metropolis of Kaduna, Nigeria. J Helminthol. 2008;82:113–118. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X07874220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino- Pereira A, de Souza FS, Lopes CWG, Pereira MJS. Prevalence of parasites in soil and dog faeces according to diagnostic tests. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masnik E. Relationships between the prevalence of Toxocara eggs in dogs’ faeces and soil. Wiad Parazytol. 2000;46:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo J, Nakashio S. Prevalence of faecal contamination in sandpits in public parks in Sapporo city, Japan. Japan Vet Parasitol. 2005;128:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizgajska H. The role of some environmental factors in contamination of soil with Toxocara spp. and other geohelminth eggs. Parasitol Int. 1997;46:67–72. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5769(97)00011-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizgajska H. Biological infection of soil on flooded areas of Wroclaw city. Wiad Parazytol. 1999;45:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizgajska H. Soil contamination with Toxocara spp. eggs in Krakow area and two nearby villages. Wiad Parazytol. 2000;46:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motazedian H, Mehrabani D, Tabatabaee SH, Pakniat A, Tavalali (2006) Prevalence of helminth ova in soil samples from public places in Shiraz..East Mediterr Health J 12(5):562–565 [PubMed]

- Nunes et al. Presence of larva migrans in sand boxes of public elementary School, Aracatuba, Brazil. Revista de Publica. 2000;34:656–658. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102000000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Lorcain P. Prevalence of Toxocara canis ova in public play grounds in the Dublin area of Ireland. J Helminthol. 1994;68:239–243. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00014401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oge H, Oge S. Quantitative comparison of various methods for detecting eggs of Toxocara canis in samples of sand. Vet Parasitol. 2000;92:75–79. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oteifa NM, Moustafa MA. The potential risk of contracting toxocariasis in Heliopolis district, Cairo Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1997;27:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo Terán LJ, Cortés Vecino JA, Villamil Jiménez LC, Prieto E. Zoonotic nematode contamination in recreational areas of Suba Bogotá. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2007;9(4):550–557. doi: 10.1590/S0124-00642007000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz ML, Simonsen M, Paschoalotti MA, Chieffi PP. Frequency of soil contamination by Toxocara canis eggs in the south region of São Paulo municipality (SP, Brazil) in a 18-month period. Rev Inst Med trop S Paulo. 2006;48:317–319. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652006000600003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai SK, Uga S, Ono K, Rai R, Matsumura T. Contamination of soil with helminth parasites in Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:388–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokicki J, Kucharska AP, Dzido J, Karczewska D(2007) Contamination of playgrounds in Gdańsk city with parasite eggs. Wiad Parazytol 53(3):227–30 [PubMed]

- Ruiz de Ybanez MR, Garijo MM, Alonso FD. Prevalence and viability of eggs of Toxocara spp. and Toxascaris leonina in public parks in Eastern Spain. J Helminthol. 2001;75:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarem VA, Sartor IF, Bergamo FM. Contamination by Toxocara spp. eggs in public parks and squares in Botucatu, sao Paulo, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;31:529–532. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86821998000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarém VA, Franco EC, Kozuki FT, Fini D, Prestes-Carneiro LE (2008) Enviromental contamination by Toxocara spp. eggs in a rural settlement in Brazil Rev Inst Med Trop S Paulo, 50: 279–281 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schottler G. Incidence of Toxocara ova in beach sand of Warnemunde in 1997. Gesundheitswesen. 1997;60:766–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T. Prevalence of Toxocara eggs in sandpits in Tokushima city and its outskirts. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:807–811. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon F, Conde L. Datos epidemiologicos sobre la toxocariosis y larva emigrante visceral en la provincial de Salamanca. Salamanca: V Congreso Nacional de Parasitologia; 1987. pp. 397–398. [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Bali HS, Kaur A (1997) Prevalence of Toxocara spp. eggs in the soil of public and private places in Ludhiana and Kellon area of Punjab, India. Epidemiol santé Anim :31–32

- Singh LA, Das SC, Baruah Indra. Observations on the soil contamination with zoonotic canine gastro intestinal parasites in selected rural areas of Tezpur, Assam. India J Parasitic Dis. 2004;28:121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Snow KR, Ball SJ, Bewick JA. Prevalence of Toxocara species eggs in the soil of five east London parks. Vet rec. 1987;120:66–67. doi: 10.1136/vr.120.3.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgan M, Colgan KM, Kennet S, Paffman J. A survey of canine toxocariasis and Toxocaral soil contamination in Essex County, New Jersey. Am J of Public Health. 1980;70:1207–1208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.70.11.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toparlak M, Gargili A, Tuzer E, et al. Contamination of children playground sandpits with Toxocara eggs in Istanbul, Turkey. Tr J Vet Anim Sci. 2002;26:317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Uga S. Prevalence of Toxocara eggs and number of faecal deposits from dogs and cats in sandpits of public parks in Japan. J Helminthol. 1993;67:78–82. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X0001289X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uga S, Ono K, Kataoka N, Safriah A, Tantlur IS, Dachlan YP, Ranuh IG. Contamination of soil with parasitic eggs in Surabaya, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1995;26:730–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uga S, Oikawa H, Lee CC, Amin babjee SM, Rai SK. Contamination of soil with parasite eggs and oocysts in and around Kualalumpur, Malaysia. Japanese J Trop Med and Hyg. 1996;24:125–127. doi: 10.2149/tmh1973.24.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uga S, Wandee N, Virasakdi C (1997) Contamination of soil with parasite eggs and oocysts in southern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public health. 24: 125-127 [PubMed]

- Valkounova J. Parasitological investigation of children’s sand boxes and dog faeces from public areas in old housing districts of Prague. Folia Parasitol. 1982;29:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez O, Ruiz A, Martinez I, Merlin PN, Tay J, Perez A. Soil contamination with Toxocara spp. eggs in public parks and home gardens from Mexico city. Boletin Chileno Parasitologico. 1996;51:54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]