Abstract

AIM: To investigate the safety and efficacy of a Hansenula-derived PEGylated (polyethylene glycol) interferon (IFN)-alpha-2a (Reiferon Retard) plus ribavirin customized regimen in treatment-naïve and previously treated (non-responders and relapsers) Egyptian children with chronic hepatitis C infection.

METHODS: Forty-six children with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection were selected from three tertiary pediatric hepatology centers. Clinical and laboratory evaluations were undertaken. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for HCV-RNA was performed before starting treatment, and again at 4, 12, 24, 48, 72 wk during treatment and 6 mo after treatment cessation. All patients were assigned to receive a weekly subcutaneous injection of PEG-IFN-alpha-2a plus daily oral ribavirin for 12 wk. Thirty-four patients were treatment-naïve and 12 had a previous treatment trial. Patients were then divided according to PCR results into two groups. Group I included patients who continued treatment on a weekly basis (7-d schedule), while group II included patients who continued treatment on a 5-d schedule. Patients from either group who were PCR-negative at week 48, but had at least one PCR-positive test during therapy, were assigned to have an extended treatment course up to 72 wk. The occurrence of adverse effects was assessed during treatment and follow up. The study was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02027493).

RESULTS: Only 11 out of 46 (23.9%) patients showed a sustained virological response (SVR), two patients were responders at the end of treatment; however, they were lost to follow up at 6 mo post treatment. Breakthrough was seen in 18 (39.1%) patients, one patient (2.17%) showed relapse and 14 (30.4%) were non-responders. Male gender, short duration of infection, low viral load, mild activity, and mild fibrosis were the factors related to a better response. On the other hand, patients with high viral load and absence of fibrosis failed to respond to treatment. Before treatment, liver transaminases were elevated. After commencing treatment, they were normalized in all patients at week 4 and were maintained normal in responders till the end of treatment, while they increased again significantly in non-responders (P = 0.007 and 0.003 at week 24 and 72 respectively). The 5-d schedule did not affect the response rate (1/17 had SVR). Treatment duration (whether 48 wk or extended course to 72 wk) gave similar response rates (9/36 vs 2/8 respectively; P = 0.49). Type of previous treatment (short acting IFN vs PEG-IFN) did not affect the response to retreatment. On the other hand, SVR was significantly higher in previous relapsers than in previous non-responders (P = 0.039). Only mild reversible adverse effects were observed and children tolerated the treatment well.

CONCLUSION: Reiferon Retard plus ribavirin combined therapy was safe. Our customized regimen did not influence SVR rates. Further trials on larger numbers of patients are warranted.

Keywords: Children, Chronic hepatitis C, Hansenula polymorpha, PEGylated interferon, Response rate, Ribavirin, Treatment

Core tip: Egypt has the highest prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the world (15%-25%) and the main (90%) genotype is type 4. Prevalence in Egyptian children was found to be 3% in upper Egypt and 9% in lower Egypt. PEG-IFN-alpha-2a or -2b and ribavirin have been used in small numbers of HCV-infected children, whose SVRs are higher in genotypes 2/3 than in genotypes 1/4. A novel 20-kDa PEG-IFN-alpha-2a (Reiferon Retard) derived from the Hansenula polymorpha expression system has been used in adults with chronic HCV, achieving an SVR ranging from 56% to 60.7%, while no studies have been reported in children before.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a serious health problem worldwide that establishes a chronic infection in up to 85% of cases[1]. Estimates of prevalence range from less than 1.0% in northern Europe to more than 2.9% in northern Africa[2]. Egypt has the highest prevalence of adult HCV infection in the world (15%-25%), especially in rural communities[3,4] and the main (90%) HCV genotype is type 4[5]. Studies of the magnitude of HCV infection in Egyptian children revealed a prevalence of 3% in upper Egypt and 9% in lower Egypt[6].

Blood transfusion was a major risk factor for HCV transmission, but has been virtually eliminated in countries where screening of blood donors has been implemented[7]. Vertical transmission of HCV infection is the most common route of acquiring HCV in infants and children[8]. It affects 4%-10% of children born to infected mothers, with the highest risk in mothers having a high viral load or co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus[9]. In a large prospective cohort from Egypt, HCV infection was determined in 10% of infants born to infected mothers: 5.47% cleared the virus by 1 year of age and 2.1% cleared the virus by 2-3 years. Persistent infection was detected in 2.43%[10]. HCV infection seems to progress more slowly to fibrosis and cirrhosis in childhood-acquired disease than in adults[11], even in those who were vertically infected, the infection has been reported as mild[9].

Treatment of chronic HCV aims at slowing disease progression, preventing complications of cirrhosis, reducing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and treating extrahepatic complications of the virus[12].

Currently, standard antiviral treatment for chronic HCV involves once weekly PEGylated interferon (PEG-IFN)-alpha injections and daily oral ribavirin. Some reports showed that among adult genotype 4 patients treated with PEG-IFN-alpha and ribavirin, 63% had a sustained virological response (SVR)[13,14].

Treatment individualization has been adopted recently as a therapeutic strategy to improve the SVR rate[15]. On treatment, virological response appears to be crucial in both tailoring the length of treatment and influencing treatment outcome. It has been reported that early virological response (EVR) at week 12 has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 65%-72% for subsequent SVR, while patients with no EVR have no possibility of SVR, with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98%-100%[16,17]. Whether EVR can be used in children, as in adults, to stop therapy early in patients destined to be non-responders, is not clear[18]. Drusano and Preston[19] hypothesized that the longer HCV-RNA remained undetectable after initial clearance, the higher the chance in attaining an SVR. Thus, it might be expected that extended treatment duration in patients with slow virological response may improve their SVRs.

Reiferon retard, a Hansenula-derived novel patented PEG-IFN, available in the Egyptian market for 6 years, is a 20 KDa PEG-IFN-alpha-2a. As stated by the manufacturer, Hansenula polymorpha represents a stable, robust and safe expression system, which is capable of reaching the highest productivity of recombinant proteins ever described. Reiferon retard has been used in adult Egyptians with safety and efficacy comparable to other PEGylated interferons[20-22].

In the current study, our aims were as follows: firstly, to investigate the efficacy and safety of Reiferon retard in attaining an SVR in treatment-naïve and previously treated (non-responders and relapsers) chronic HCV infected children; secondly, to assess the effect of tailoring treatment on the SVR [by decreasing the interval between injections (5 d vs 7 d) and prolonging duration of therapy (72 wk vs 48 wk)] based on the on-treatment virological response; thirdly to assess predictors of an SVR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This study included 46 children with compensated chronic hepatitis C infection recruited from three pediatric hepatology tertiary centers: the Pediatric department in Yassin Abdel Ghaffar Charity Center for Liver Disease and Research; Cairo University Pediatric Hospital; and the Pediatric Hepatology department, National Liver Institute, between February 2009 and July 2009. The study was completed on August 2011. Diagnosis was based on serological and virological tests; HCV-antibody (Ab) by a third generation enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and qualitative and quantitative PCR for HCV-RNA.

Criteria for inclusion were children aged 3-19 years with compensated chronic HCV infection (HCV-RNA positive by PCR for more than 6 mo), whose hemoglobin (Hb) was ≥10 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 1500/mm3, platelet count > 75000/mm3, and who had normal random blood sugar, serum creatinine, serum ferritin, thyroid function tests and lipid profile and no other associated liver disease [autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection]. Liver biopsy was mandatory for enrollment.

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis, any other cause of liver disease associating HCV infection, body mass index (BMI) ≥ 95 percentile, severe psychiatric conditions, uncontrolled seizure disorder, decompensated cardiovascular disease, renal insufficiency, evidence of retinopathy, decompensated thyroid disease, hemoglobinopathy, immunologically mediated diseases or any other chronic illness requiring long term immunosuppressive drugs or previous IFN therapy within one year of enrollment, were excluded from the study. A signed informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all the patients before enrollment in the study. The Research Ethics Committee in the three participating centers approved this study.

Treatment regimens and follow up protocol

All patients were assigned to receive a weekly subcutaneous injection of PEG-IFN-alpha-2a (Reiferon Retard; Minapharm, Rhein-Biotech, Germany) in a dose of 100 μg/m2 per week plus ribavirin 15 mg/kg daily in two divided doses for a total of 12 wk. Patients were then divided into two groups according to HCV-RNA results at week 12.

Group I comprised patients who continued treatment on a weekly basis (7-d schedule). This group included patients who were HCV-RNA negative at week 12 and those who had < 1 log decrease in HCV-RNA viremia. Group II comprised patients who continued treatment on a 5-d schedule. This group included patients who had ≥ 1 log decrease in viremia (compared to pre-treatment level) at week 12.

At week 48, patients who were PCR-positive stopped treatment. Patients who were persistently HCV-RNA negative by PCR (at weeks 4, 12, 24 and 48) also stopped treatment and their SVR was checked 6 mo after stopping treatment (SVR 1). Patients who were PCR-negative at week 48, but had at least one PCR-positive test during therapy at weeks 4, 12, or 24 (delayed response or breakthrough) were assigned to have an extended treatment course of 6 mo duration. PCR was performed at 72 wk in those patients to detect end of treatment response and those who were HCV-RNA negative, were tested after a further 6 mo for an SVR (SVR 2).

All patients had their full medical history taken and received a thorough clinical examination before starting treatment, with stress laid on the duration and possible cause of infection, previous trial of antiviral therapy, psychiatric history and fundus examination. The occurrence of adverse effects was assessed during the treatment and follow up periods.

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory investigations, including complete blood count (CBC), albumin, alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, prothrombin time (PT), kidney function tests, alpha-fetoprotein, thyroid function tests (T3, T4, TSH), lipid profile (triglycerides, cholesterol and low and high density lipoproteins), serum autoantibodies (anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies and liver-kidney microsomal antibodies) and PT were performed for every patient before starting treatment. CBC, ALT and AST were done weekly for the first month, every two weeks for 2 mo and monthly thereafter. PT was performed at the third month and at the end of treatment. Viral markers [HCV-Ab (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), HBV surface antigen, HBV core immunoglobulin (Ig)M and IgG Abs (all from Dia Sorin, Saluggia, Italy)] were performed using ELISA, according to the manufacturer instructions. Real-time PCR for HCV-RNA was performed using COBAS® Ampliprep/COBAS® TaqMan®, Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ, 08876 United States (the detection limit was 15 IU/mL). According to the viral load, viremia was classified arbitrarily for descriptive purpose into low (≤ 2 × 105 IU/mL), moderate (> 2 × 105-2 × 106 IU/mL) and high viremia (> 2 × 106 IU/mL). HCV genotyping/subtyping was done by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, using restriction enzymes HaeIII, RsaI, MvaI and HinfI on PCR-amplified 5’-untranslated region.

Dose modification regimen

The doses of PEG-IFN and ribavirin were modified according to ANC, Hb and platelets. If Hb dropped to < 10 g/dL, ribavirin dose was reduced by 25% and if to < 7.5 mg/dL, erythropoietin was administered. If ANC was 500-800/mm3 and/or platelet count < 80000/mm3, the IFN dose was reduced by 25%. If ANC was 300-500/mm3, the IFN dose was reduced by 50%. If ANC < 300/mm3 and/ or platelet count ≤ 50000/mm3, the IFN dose was skipped and resumed later after the count reached safe levels.

Definitions of virological response

Virological responses during therapy were defined as reported by Ghany et al[23].

Liver biopsy and histopathological evaluation

Liver biopsy was performed for all patients except one who had hemophilia. Hepatic necroinflammatory activity and liver fibrosis were evaluated according to Ishak staging and grading scores[24]. Necroinflammatory activity was classified into mild (score 1-5), moderate (score 6-8), and severe (score 9-18). Fibrosis was classified into mild (stage 1), moderate (stages 2-3), and severe fibrosis or cirrhosis (stages 4-6)[25]. Steatosis was graded semi-quantitatively by determining the percentage of affected hepatocytes and the following scoring system was employed: grade 0: < 5%, grade 1: 5%-33%, grade 2: 34%-66%, grade 3: > 66%[26].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive results were expressed as mean ± SD or number (percentage) of individuals with a condition. Statistical significance between groups was tested either by a non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney U test), Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were expressed as percentages. Results were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

Patient population characteristics

Forty-six children were enrolled in the study. They were 33 boys and 13 girls, aged between 4 and 19 years (mean 10.32 ± 3.46 years). Forty-four patients completed the full course of treatment and follow up regimen, while two patients did not show up after completing 48 wk treatment; therefore, they could not be evaluated for SVR. Two patients had glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, one had hemophilia and one had situs inversus. The demographic and epidemiologic characteristics of the studied population are summarized in Table 1. Blood transfusion was considered a possible risk factor in 34.8% of patients, while mother to child transmission was considered a possible one in 17.4% of them. Eighteen patients (39.1%) had an HCV infected family member and most of the patients (43 out of 46) had more than one possible risk factor of infection, while in three patients no possible source of infection was identified.

Table 1.

Demographic, laboratory and histopathological parameters in all patients n (%)

| Parameter | All patients (n = 46) |

| Age (yr) | 10.32 ± 3.46 |

| Male | 33 (71.7) |

| Duration of infection (yr) | 5.29 ± 3.97 |

| BMI | 18.20 ± 2.77 |

| Possible risk of infection | |

| Surgery | 14 (30.4) |

| Blood transfusion | 16 (34.8) |

| Tonsillectomy | 5 (10.9) |

| Circumcision | 33 (71.7) |

| Minor procedures1 | 30 (65.2) |

| Vertical transmission | 8 (17.4) |

| Family contact | 18 (39.1) |

| More than one possible risk | 43 (93.5) |

| Unknown risk factor | 3 (6.5) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.5 ± 1.1 |

| ANC (× 103/μL) | 3.13 ± 1.7 |

| Platelets (× 103/μL) | 280.7 ± 82.4 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.1 ± 0.37 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 56.6 ± 55.03 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 49.2 ± 31.65 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L) | 32.1 ± 26.6 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 212.5 ± 96.1 |

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 12.9 ± 0.62 |

| Hepatomegaly (US) | 3 (15.9) |

| Splenomegaly (US) | 3 (15.9) |

| Viremia (IU/mL) | |

| Low (≤ 2 × 105 IU/mL) | 19 (41.3) |

| Moderate (> 2 × 105 - 2 × 106 IU/mL) | 25 (54.3) |

| High (> 2 × 106 IU/mL) | 2 (4.3) |

| Genotype: | |

| 4a | 30 (65.2) |

| 4b | 8 (17.4) |

| Not determined | 8 (17.4) |

| Fibrosis stage | |

| Absent | 13 (28.9) |

| Mild | 30 (66.7) |

| Moderate | 2 (4.4) |

| Activity grade | |

| Mild | 44 (97.8) |

| Moderate | 1 (2.2) |

Minor procedures were: Sutures, abscess drainage, ICU hospitalization, endoscopy, ear piercing, tattooing, prolonged hospitalization and dental care. US: Ultrasound; BMI: Body mass index.

The mean of expected duration of infection was 5.29 ± 3.97 years and the mean BMI was 18.20 ± 2.77. Low, moderate and high viremic loads were found in 41.3%, 54.3% and 4.3% of patients, respectively. HCV genotype was detected in 38 out of 46 patients. All were genotype 4; 30 (65.2%) were 4a and 8 (17.4%) were 4b. The genotype could not be determined in eight patients. The majority of patients had mild fibrosis (66.7%) and mild activity (97.8%) in their liver biopsy. Fibrosis was absent in 28.9% of patients, while only 4.4% had moderate fibrosis.

Response to treatment in the group as a whole

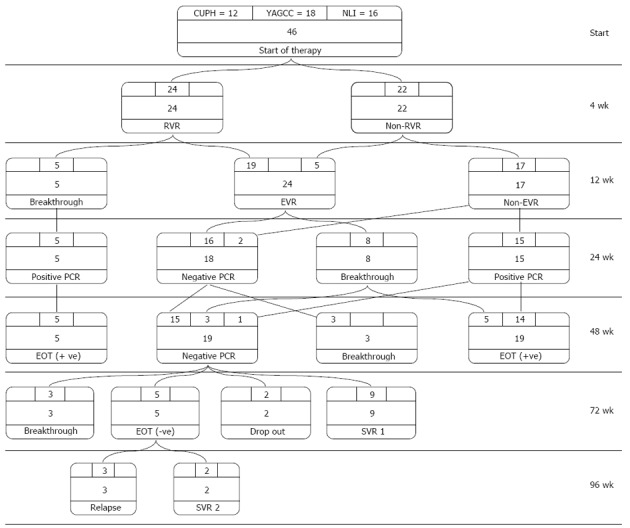

In the group as a whole, only 11 out of 46 (23.9%) showed an SVR. There were 14 (30.4%) non-responders, where HCV-RNA was detectable throughout treatment. Breakthrough was seen in 18 (39.1%) patients and delayed response in eight (17%) patients. Relapse occurred in one (2.17%) patient. Two patients had an end of treatment response (ETR) but were lost to follow up and dropped out of the evaluation of SVR (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the treatment algorithm according to PCR results for all cases during treatment and follow up periods.

Table 2.

Response outcome

| Response type | n = 46 |

| End of treatment response | 13 (28.2) |

| SVR | 11 (23.9) |

| Dropped out SVR | 2 (4.3) |

| Non-responder | 14 (30.4) |

| Breakthrough | 18 (39.1) |

| Delayed responders ended by breakthrough | 8 (17.4) |

| Breakthrough ended at 48 wk as non-responders | 8 (17.4) |

| Breakthrough ended at 72 wk by relapse | 2 (4.3) |

| Relapse | 1 (2.17) |

Two patients who had end of treatment response (ETR) but were lost to follow up. SVR: Sustained virological response.

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm and response to therapy. At weeks 4, 24 (52.17%) patients attained a rapid virological response (RVR) and 22 (47.82%) had no RVR. At week 12, five patients (10.86%) had breakthrough, while the remaining 19 patients had an early virological response (EVR). Those patients, in addition to five patients who turned negative from ones with no RVR formed a total of 24 (52.17%) patients with EVR. At week 24, those who had breakthrough continued to be polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive and eight patients from those with EVR had breakthrough. The remaining 16 patients, in addition to two patients from those with no EVR, turned PCR-negative, making a total of 18 (39.13%) patients with negative PCR. At week 48, three of those 18 patients had breakthrough, while the remaining 15 patients and one patient from those positive at week 24, in addition to three patients who had breakthrough at week 24 (making a total of 19 patients), had negative PCR. Of the 19 negative-PCR patients, nine had an SVR at week 72 and two patients dropped out. The remaining eight patients had an extended 6-month therapy (three patients had breakthrough and five patients were PCR-negative at their ETR). At week 96, three out of five patients with extended course had relapse, while the other two patients attained an SVR, making the total SVR 11 out of 44 (25%). EOT: End of treatment.

Predictors of response

There was no significant statistical difference in the response rate of the three centers. Responders were nine males (9/31 = 29.1%) and two females (2/13 = 15.4%). Twelve patients had history of a previous treatment trial; two (18.2%) of them achieved SVR while nine (81.8%) were non-responders. The last one achieved ETR but was lost to follow up. The type of previous treatment (short acting IFN vs PEG-IFN) did not affect the response to retreatment. On the other hand, the SVR was significantly higher in previous relapsers than in previous non-responders (P = 0.039). Seven out of the 11 (64%) responders had low viremia. Patients infected with HCV subtypes, whether 4a or 4b, had similar response rates (4/28 and 1/8 respectively). The majority of patients (44) had mild activity; 11 out of them had an SVR (13 achieved ETR). Mild fibrosis was seen in 30 patients; 10 (33%) out of them achieved an SVR (12 achieved ETR), while among 13 patients with absent fibrosis, only one (7.7%) achieved an SVR. All patients with steatosis (4 patients) did not achieve an SVR (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison between patients with sustained virological response and non-sustained virological response according to different variables n (%)

| Parameter | SVR | Non-SVR | P value |

| (n = 11) | (n = 33) | ||

| Center: | |||

| CUPH | 1 (9) | 9 (27.3) | 0.330 |

| YAGCC | 5 (45.5) | 13 (39.4) | |

| NLI | 5 (45.5) | 11 (33.3) | |

| Age (yr) | 9.9 ± 3.76 | 10.39 ± 3.45 | 0.385 |

| Male | 9 (81.8) | 22 (66.7) | 0.340 |

| Expected duration of infection (yr) | 3.77 ± 3.28 | 5.61 ± 4.02 | 0.341 |

| Previous treatment trial | 2 (18.2) | 9 (27.3) | 0.546 |

| Previous treatment type2 | |||

| Short-acting IFN + RBV | 2 (100) | 8 (88.9) | 1.000 |

| PEG-IFN + RBV | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Previous response type2 | |||

| Non-responder | 0 (0) | 7 (77.8) | 0.0391 |

| Relapser | 2 (100) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Possible cause of infection | |||

| Surgery | 4 (36.4) | 10 (30.3) | 0.709 |

| Blood transfusion | 4 (36.4) | 11 (33.3) | 0.854 |

| Tonsillectomy | 1 (9.1) | 4 (12.1) | 0.784 |

| Circumcision | 9 (81.8) | 22 (66.7) | 0.340 |

| Minor procedures | 8 (72.7) | 22 (66.7) | 0.709 |

| Vertical transmission | 2 (18.2) | 6 (18.2) | 1.000 |

| Family contact | 4 (36.4) | 14 (42.4) | 0.723 |

| Injection interval: | |||

| 5 d | 1 (9) | 16 (48.5) | 0.0201 |

| 7 d | 10 (91) | 17 (51.5) | |

| Treatment duration: | |||

| 48 wk | 9 (81.8) | 27 (81.8) | 0.940 |

| 72 wk | 2 (18.2) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Genotype: | |||

| 4a | 4 (80) | 24 (77.4) | 0.890 |

| 4b | 1 (20) | 7 (22.6) | |

| Viral load: | |||

| Low | 7 (64) | 11 (33.4) | 0.180 |

| Moderate | 4 (36) | 20 (60.6) | |

| High | 0 (0) | 2 (6.0) | |

| Histological Activity: | |||

| Mild | 11 (100) | 31 (96.9) | 0.550 |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | |

| Fibrosis stage: | |||

| No | 1 (9.1) | 12 (37.5) | 0.112 |

| Mild | 10 (90.9) | 18 (56.3) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Steatosis: | |||

| No | 11 (100) | 28 (87.5) | 0.460 |

| Mild | 0 (0) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) |

Significant;

Percentages were calculated for those with previous treatment trial. SVR: Sustained virological response.

Effect of tailoring treatment according to on-treatment response

Of the 17 patients who followed the 5-d schedule, one patient (1/17=6%) achieved an SVR. Extended treatment (72 wk) was given to eight patients. Whatever the duration of treatment, a quarter of the cases in each group achieved an SVR (Table 3).

SVR according to rapid virological response and EVR

Patients who achieved an SVR (11/44) had 81.8% rapid virological response (RVR), 90.9% EVR, 100% negative PCR at 24 wk of treatment, and 100% ETR. These data are highly significant (Table 4). RVR and EVR showed high sensitivity (81.8% and 90.9% respectively), but low specificity (60.6% and 63.6% respectively) in predicting an SVR. They had a very good NPVs of 90.9% and 95.45% respectively (Table 5).

Table 4.

Rapid virological response, early virological response, polymerase chain reaction at week 24, and end of treatment response in sustained virological response vs non-sustained virological response n (%)

| Parameter | RVR | EVR | PCR at week 24 | ETR |

| SVR (n = 11) | 9 (81.8) | 10 (90.9) | 11 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Non-SVR (n = 33) | 13 (39.4) | 12 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| P value | 0.0151 | 0.0021 | < 0.0011 | < 0.0011 |

Significant. SVR: Sustained virological response; ETR: End of treatment response; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; EVR: Early virological response.

Table 5.

Predictive value of rapid virological response and early virological response to sustained virological response

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

| RVR | 81.8 | 60.6 | 40.9 | 90.9 |

| EVR | 90.9 | 63.6 | 45.45 | 95.45 |

PPV: Positive predictive value; RVR: Rapid virological response; NPV: Negative predictive value; EVR: Early virological response.

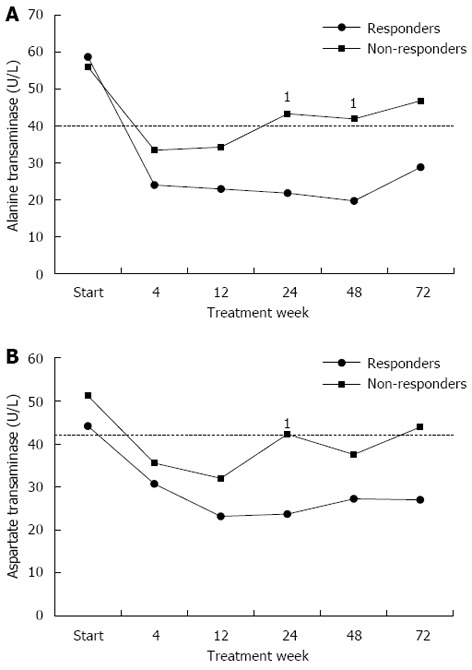

Effect of treatment on liver enzymes

During treatment, ALT and AST normalized in both responder and non-responder groups at week 4 and were maintained normal in responders till the end of the treatment, whereas they increased again significantly in non-SVR group from week 12 onwards (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase mean levels during treatment in responders and non-responders. A: Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) mean levels remained normal in responders all through the follow up period, while in non-responders, after starting as normal, they increased again to significantly higher levels than in responders from week 12 onwards, especially at weeks 24 and 48 (1P = 0.007, 0.003 respectively); B: Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) mean levels remained normal in responders all through the follow up period, while in non-responders, after starting as normal, they significantly increased again in week 24 (1P = 0.007) and once more in week 72. The dashed line represents the upper limit of normal.

Treatment safety

Regarding the safety of combined therapy, all side effects were temporary and mild (Table 6). Fever was seen in the first few weeks of treatment in 27 (58.7%) patients and flu-like symptoms appeared in 15 (32.6%) patients. Both anemia and neutropenia were treated by reduction or skipping of doses.

Table 6.

Treatment side effects n (%)

| Side effect | n = 46 |

| Flu like symptoms | 15 (32.6) |

| Headache | 15 (32.6) |

| Fever | 27 (58.7) |

| Injection site reaction | 7 (15.2) |

| Itching | 1 (2.2) |

| Fainting | 1 (2.2) |

| Vomiting | 6 (13) |

| Nervousness | 1 (2.2) |

| Loss of appetite | 10 (21.7) |

| Sleeplessness | 1 (2.2) |

| Rigors | 3 (6.5) |

| Neutropenia | 6 (13) |

| Anemia (Hb 8.5-10 g/dL) | 8 (17.4) |

| Anemia (Hb ≤ 8.5 g/dL) | 2 (4.3) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (4.3) |

| Arthralgia | 5 (10.9) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (8.7) |

DISCUSSION

Since the introduction of IFN, attempts have been made to introduce novel IFNs with the aim of increasing therapeutic efficacy, reducing adverse events and/or reducing the cost of therapy.

The current study used the Hansenula-derived PEG-INF-alpha-2a (a 20 KDa Reiferon Retard) plus ribavirin customized regimen for treatment of chronic HCV infected children.

To date, only four Egyptian studies investigating the efficacy and safety profile of the Hansenula-derived PEG-IFN-alpha-2aplus ribavirin for the treatment of adult Egyptian patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C are available. The SVRs ranged from 56% to 60.7% following 48 wk of combination therapy[20,27-29]. These results are comparable to those obtained using the existing two PEG-IFN-alpha-2a and alpha-2b agents for treatment of genotype 4 in adults[30-33], with the exception of a single report that demonstrated an SVR rate of 33.3% after treatment with PEG-IFN-alpha-2b[34].

In children, Wirth et al[35] evaluated the efficacy and safety of PEG-IFN-alpha-2b and ribavirin, disclosing a high SVR of 90% in genotypes 2 and 3, and 53% for children with genotype 1. Another large trial concluded that children with HCV genotype 1 had a 47% response rate with PEG-IFN-alfa-2a/ribavirin[36].

The results of a meta-analysis of eight trials[35-42] performed in 2013 by Druyts et al[43], indicated that EVR and SVR were both higher for genotypes 2/3 (87% and 89%, respectively) than for genotypes 1/4 (61% and 52%, respectively). The sensitivity analysis comparing PEG-IFN-alfa-2a and PEG-IFN-alfa-2b indicated that these two treatments were comparable in terms of efficacy and safety.

In the present study, the ETR was 28.2% (two cases were lost to follow up) and 23.9% showed an SVR. Breakthrough was seen in 39.1%. One patient showed relapse and 14 (30.4%) were non-responders.

The lower proportion of SVRs in genotype 4 infected children in this trial compared with other trials in adults using the same IFN type and in children using other IFN types might be partially explained by the high percentage of previous non-responders (9/12) and relapsers (2/12) included in the study (12/46). Of those 12, only two showed an SVR (they were the previous relapsers).

Retreatment of children who do not demonstrate an SVR may be beneficial in patients who relapse or show viral breakthrough during treatment, but is not helpful in non-responders[39,44]. Of our patients, 39.1% had breakthrough and 2.17% showed relapse giving an opportunity for retreatment.

In this study, although the relapse rate was comparable to other studies[39,43,45], there was a very high rate of breakthrough, which may also explain our low response rate, as the EVR was 24/46 (52%); however, this dropped to an ETR of 13/46 (28.2%) because of the high rate of breakthrough (39.1%).

The cause of viral breakthrough is not well understood. Some have postulated that it occurs as a result of neutralizing antibodies to IFN, downregulation of IFN receptors or development of IFN resistance and emergence of quasispecies that are less sensitive to IFN[46]. Also, the overall adherence to ribavirin significantly influences the SVR. Notably only one (2%) patient had ribavirin dose reduction in this study.

The 5-d schedule did not affect the response rate. Treatment duration (whether 48 wk or extended course to 72 wk) gave the same response rate. In the extended treatment group, four patients received this extended treatment because of breakthrough (three at week 24 and one at week 12). None benefited from the 72 wk treatment. On the other hand, two out of the four patients who received the extended course because of delayed response achieved an SVR.

In the study of Druyts et al[43], only 4% of patients discontinued treatment because of breakthrough.

In our study, 10 out of 11 patients (90.9%) who had achieved SVR had EVR. EVR had a PPV of 45.45% and an NPV of 95.45% for SVR. Nine of the SVR patients (81.8%) had RVR. RVR had a PPV of 40.9% and an NPV of 90.9% for SVR. Thus, EVR is slightly better than RVR for the negative and positive prediction of SVR. According to Druyts et al[43], most of the patients who achieved an EVR (70%) also achieved an SVR (58%).This emphasizes that the EVR is crucial and cost-effective in selecting those who can discontinue treatment at week 12 if they remain positive.

According to the present study, factors related to better response were male gender, short duration of infection, low viral load, mild activity and mild fibrosis. Patients with high viral load and absence of fibrosis showed failure to respond to treatment. In addition, all patients with steatosis (four patients) failed to achieve an SVR. Furthermore, those with previous treatment trials, namely the previous non-responders, showed failure of retreatment with IFN/ribavirin. Novel direct acting antiviral drugs (DAAs), which target specific hepatitis C virus enzymes, showed encouraging results in adults when used alone or in combination with IFN/ribavirin. DAAs have been studied in relapsers, partial responders and null responders to prior PEG-IFN/ribavirin therapy. The SVR rates were approximately 85%, 57%, and 31%, respectively[47]. A Japanese study of 10 prior null responders with HCV genotype 1b found 90% achieved an SVR using a combination of two DAAs[48]. Such regimens may be of benefit and worth future clinical trials in children to ensure safe and appropriate use of these new agents, especially in those with treatment failure to IFN-based therapy.

In other studies[36,39,49], predictors of response were early viral response, lower baseline HCV-RNA levels, female sex, non-maternal route of transmission of HCV, absence of steatosis on liver histology, and moderate inflammation on liver biopsy.

Constitutional symptoms are almost universal in children undergoing IFN therapy. Bone marrow suppression induced by IFN constitutes the next most common toxicity after constitutional symptoms, occurring in approximately one third of treatment recipients[35,36]. In the current study, only mild reversible adverse effects were observed. Fever was seen in the first few weeks of treatment in 58.7% of patients, and both flu-like symptoms and headaches appeared in 32.6% of patients. Anemia and neutropenia were found at a rate of 21.7% and 13%, respectively, and were treated by reduction or skipping of doses; none of the patients developed thrombocytopenia. According to a meta-analysis reported in 2013[43], neutropenia was the most common hematological adverse event evaluated (32%), whereas anemia and thrombocytopenia were less frequent (11% and 5%, respectively). Dose reductions for neutropenia occurred in 38% of patients in the North American study and 12% in the European study respectively[35,36]. Drug cessation because of neutropenia did not occur in either study. In the North American study[36], there was no significant thrombocytopenia, and in the European study, one patient discontinued therapy at week 42 because of thrombocytopenia (platelet count 45000 cells/mm3)[35].

The strength of this study is that it is a multicenter one; including 46 children with chronic HCV, using the Hansenula-derived PEG-IFN-alpha-2a (a 20 KDa Reiferon Retard) plus ribavirin, using customized treatment and reporting the response to treatment in children. The limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size.

In conclusion, combined therapy in the form of Reiferon retard plus ribavirin was safe. Children tolerated the treatment well, with only mild reversible adverse effects. The end of treatment response was 28.2% and the factors related to better response were male gender, short duration of infection, low viral load, mild activity and mild fibrosis. Our customized regimen did not influence the SVR rate, and future clinical trials with novel antiviral drugs may be of benefit to those with treatment failure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02027493).

COMMENTS

Background

Despite recent success after the introduction of combination therapy with interferon (IFN)-alpha and ribavirin, genotype 4 is considered difficult-to-treat. Approximately 60% of patients fail to respond. Resistance to antiviral therapy remains a serious problem in the management of chronic hepatitis C. Establishing novel therapeutic agents, treatment customization, and determining the factors associated with better response rates remain the targets of many researchers.

Research frontiers

Reiferon Retard is a novel 20-kDa PEGylated (PEG)-IFN-alpha-2a derived from the Hansenula polymorpha expression system. It has been used in adults with chronic hepatitis C virus to achieve a sustained virological response (SVR) ranging from 56% to 60.7%, while no studies have been reported in the pediatric population.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The current study is the first to use the novel Hansenula-derived PEG-IFN-alpha-2a in children. Treatment customization regarding duration (72 wk vs extended course of 48 wk) and IFN injection frequency (5-d schedule vs 7-d schedule) demonstrated safety and tolerability in children, yet did not improve response rates. This may be, in part, explained by the high percentage of previous non-responders included in the study.

Applications

The study results suggest that combined therapy in the form of Reiferon Retard plus ribavirin was safe. Children tolerated the treatment well, with only mild reversible adverse effects. Treatment duration extension and/or shortening the injection interval did not improve the SVR rates. Male gender, short duration of infection, low viral load, mild activity, and mild fibrosis are associated with favorable response.

Terminology

The Hansenula polymorpha expression system is known for its superior characteristics. Increasing numbers of products and protein candidates have been derived from this expression system; therefore, it has been gaining greater popularity in recent years. Hansenula polymorpha represents an absolute mitotic stable, robust and safe expression system, which boasts one of the highest productivities ever described for a recombinant protein, with maximum purity and high biological activity. In addition, production processes based on Hansenula polymorpha technology are very cost effective. The cost effectiveness is strongly related to very short fermentation times and to a significantly reduced number of downstream steps, resulting in a higher purity, with no forms of oxidized interferon being detected.

Peer review

This is a well done study, presented in a detailed fashion. Though it is already known that extending treatment beyond 48 wk achieves little extra benefit, your paper convincingly proves the case for genotype 4 infected children (including prior non-responders), which is a not so widely studied sub-group.

Footnotes

Supported by Yassin Abdel-Ghaffar Charity Center for Liver Disease and Research, Cairo, Egypt, in collaboration with the National Liver Institute, Menofiya University, Egypt and Cairo University Pediatric Hospital, Cairo, Egypt; Antiviral medications (PEG-IFN-alpha-2a and ribavirin) and HCV genotyping were offered as donation from Yassin Abdel-Ghaffar Charity Center for Liver Disease and Research, Cairo, Egypt

P- Reviewers: Antonelli A, Gelderblom HC, Gara N S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis C: the clinical spectrum of disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:15S–20S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster DP, Klenerman P, Collier J, Jeffery KJ. Development of novel treatments for hepatitis C. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:108–117. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Wahab MF, Zakaria S, Kamel M, Abdel-Khaliq MK, Mabrouk MA, Salama H, Esmat G, Thomas DL, Strickland GT. High seroprevalence of hepatitis C infection among risk groups in Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:563–567. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, El Khoby T, Abdel-Wahab Y, Aly Ohn ES, Anwar W, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887–891. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamal SM, Nasser IA. Hepatitis C genotype 4: What we know and what we don’t yet know. Hepatology. 2008;47:1371–1383. doi: 10.1002/hep.22127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Raziky MS, El-Hawary M, Esmat G, Abouzied AM, El-Koofy N, Mohsen N, Mansour S, Shaheen A, Abdel Hamid M, El-Karaksy H. Prevalence and risk factors of asymptomatic hepatitis C virus infection in Egyptian children. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1828–1832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch MP, Glynn SA, Stramer SL, Strong DM, Caglioti S, Wright DJ, Pappalardo B, Kleinman SH. A new strategy for estimating risks of transfusion-transmitted viral infections based on rates of detection of recently infected donors. Transfusion. 2005;45:254–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack CL, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Gupta N, Leung D, Narkewicz MR, Roberts EA, Rosenthal P, Schwarz KB. NASPGHAN practice guidelines: Diagnosis and management of hepatitis C infection in infants, children, and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:838–855. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318258328d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jara P, Hierro L. Treatment of hepatitis C in children. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:51–61. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shebl FM, El-Kamary SS, Saleh DA, Abdel-Hamid M, Mikhail N, Allam A, El-Arabi H, Elhenawy I, El-Kafrawy S, El-Daly M, et al. Prospective cohort study of mother-to-infant infection and clearance of hepatitis C in rural Egyptian villages. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1024–1031. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jara P, Resti M, Hierro L, Giacchino R, Barbera C, Zancan L, Crivellaro C, Sokal E, Azzari C, Guido M, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in childhood: clinical patterns and evolution in 224 white children. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:275–280. doi: 10.1086/345908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee HS, Currie SL, Darling JM, Wright TL. Management and treatment of hepatitis C viral infection: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center program and the National Hepatitis C Program office. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2360–2378. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamal SM. Hepatitis C genotype 4 therapy: increasing options and improving outcomes. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varghese R, Al-Khaldi J, Asker H, Fadili AA, Al Ali J, Hassan FA. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 with peginterferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:218–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buti M, Lurie Y, Zakharova NG, Blokhina NP, Horban A, Teuber G, Sarrazin C, Balciuniene L, Feinman SV, Faruqi R, et al. Randomized trial of peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for 48 or 72 weeks in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 and slow virologic response. Hepatology. 2010;52:1201–1207. doi: 10.1002/hep.23816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo MW, Fried MW. Guidelines for stopping therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:17–21. doi: 10.1007/s11894-004-0021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craxì A. Early virologic response with pegylated interferons. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36 Suppl 3:S340–S343. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(04)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K, Doucette K, Wong W, Girgrah N, Yoshida E, Renner E, Wong P, Deschênes M. Management of chronic hepatitis C: consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21 Suppl C:25C–34C. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drusano GL, Preston SL. A 48-week duration of therapy with pegylated interferon alpha 2b plus ribavirin may be too short to maximize long-term response among patients infected with genotype-1 hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:964–970. doi: 10.1086/382279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esmat G, Fattah SA. Evaluation of a novel pegylated interferon alpha-2a (Reiferon Retard®) in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C - genotype 4. Dig Liver Disease Suppl. 2009;3:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esmat G, Hadi G. A Novel PEG-IFN-alpha2A in Chronic HCV Genotype 4 Patients. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:691–712. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehab HM. Efficacy of Nitazoxanide in the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Sponsors and Collaborators. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Egyptian Railway Hospital; Cairo University (EGY). [cited; 2013. p. Dec 27]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01276756 NLM Identifier: NCT01276756. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esmat G, Metwally M, Zalata KR, Gadalla S, Abdel-Hamid M, Abouzied A, Shaheen AA, El-Raziky M, Khatab H, El-Kafrawy S, et al. Evaluation of serum biomarkers of fibrosis and injury in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2007;46:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giannattasio A, Spagnuolo MI, Sepe A, Valerio G, Vecchione R, Vegnente A, Iorio R. Is HCV infection associated with liver steatosis also in children? J Hepatol. 2006;45:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afifi MT, El-Gohary A. Evaluation of the effi cacy and safety of pegylated interferon α2a 160 μg (reiferon retard) and ribavirin combination in chronic HCV genotype 4 patients (Poster Abstracts II). Proceedings of Asian Pacific Digestive Week; 2010 Sep 19-22; Kuala Lampur, Malaysia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:A79–A176. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amer M, El Sayed A, Afifi MMA, Awad SE. Response to Combination Therapy with a Hansenula-derived Pegylated-Iinterferon alpha-2-a and Ribavirin in Naive Egyptian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 4. Proceedings of 18th United European Gastroenterology Week; 2010 Oct 23-27; Barcelona, Spain, A321 P1064. Gut. 2010;59:A321. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taha AA, El-Ray A, El-Ghannam M, Mounir B. Efficacy and safety of a novel pegylated interferon alpha-2a in Egyptian patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:597–602. doi: 10.1155/2010/717845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derbala M, Rizk N, Al-Kaabi S, Amer A, Shebl F, Al Marri A, Aigha I, Alyaesi D, Mohamed H, Aman H, et al. Adiponectin changes in HCV-Genotype 4: relation to liver histology and response to treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:689–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derbala MF, El Dweik NZ, Al Kaabi SR, Al-Marri AD, Pasic F, Bener AB, Shebl FM, Amer AM, Butt MT, Yakoob R, et al. Viral kinetic of HCV genotype-4 during pegylated interferon alpha 2a: ribavirin therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:591–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Makhzangy H, Esmat G, Said M, Elraziky M, Shouman S, Refai R, Rekacewicz C, Gad RR, Vignier N, Abdel-Hamid M, et al. Response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1576–1583. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamal SM, El Kamary SS, Shardell MD, Hashem M, Ahmed IN, Muhammadi M, Sayed K, Moustafa A, Hakem SA, Ibrahiem A, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C: The role of rapid and early virologic response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1732–1740. doi: 10.1002/hep.21917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derbala M, Amer A, Bener A, Lopez AC, Omar M, El Ghannam M. Pegylated interferon-alpha 2b-ribavirin combination in Egyptian patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:380–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth S, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calzado MA, Bortolotti F, Zancan L, Jara P, Shelton M, Kerkar N, Galoppo M, Pedreira A, et al. High sustained virologic response rates in children with chronic hepatitis C receiving peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2010;52:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz KB, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Murray KF, Molleston JP, Haber BA, Jonas MM, Rosenthal P, Mohan P, Balistreri WF, Narkewicz MR, et al. The combination of ribavirin and peginterferon is superior to peginterferon and placebo for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:450–458.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Ali J, Owayed S, Al-Qabandi W, Husain K, Hasan F. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 in adolescents. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:156–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jara P, Hierro L, de la Vega A, Díaz C, Camarena C, Frauca E, Miños-Bartolo G, Díez-Dorado R, de Guevara CL, Larrauri J, et al. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon-alpha2b and ribavirin combination therapy in children with chronic hepatitis C infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:142–148. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318159836c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pawłowska M, Pilarczyk M, Halota W. Virologic response to treatment with Pegylated Interferon alfa-2b and Ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in children. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CR616–CR621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sokal EM, Bourgois A, Stéphenne X, Silveira T, Porta G, Gardovska D, Fischler B, Kelly D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in children and adolescents. J Hepatol. 2010;52:827–831. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirth S, Pieper-Boustani H, Lang T, Ballauff A, Kullmer U, Gerner P, Wintermeyer P, Jenke A. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin treatment in children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1013–1018. doi: 10.1002/hep.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang HF, Yang XJ, Zhu SS, Dong Y, Chen DW, Jia WZ, Xu ZQ, Mao YL, Tang HM. [An open-label pilot study evaluating the efficacy and safety of peginterferon alfa-2a combined with ribavirin in children with chronic hepatitis C] Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Zazhi. 2005;19:185–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Druyts E, Thorlund K, Wu P, Kanters S, Yaya S, Cooper CL, Mills EJ. Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:961–967. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerner P, Hilbich J, Wenzl TG, Behrens R, Walther F, Kliemann G, Enninger A, Wirth S. Re-treatment of children with chronic hepatitis C who did not respond to interferon-alpha treatment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:187–190. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d9c7f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mangia A, Minerva N, Bacca D, Cozzolongo R, Ricci GL, Carretta V, Vinelli F, Scotto G, Montalto G, Romano M, et al. Individualized treatment duration for hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:43–50. doi: 10.1002/hep.22061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vuillermoz I, Khattab E, Sablon E, Ottevaere I, Durantel D, Vieux C, Trepo C, Zoulim F. Genetic variability of hepatitis C virus in chronically infected patients with viral breakthrough during interferon-ribavirin therapy. J Med Virol. 2004;74:41–53. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, Focaccia R, Younossi Z, Foster GR, Horban A, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chayama K, Takahashi S, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ikeda K, Ishikawa H, Watanabe H, McPhee F, Hughes E, Kumada H. Dual therapy with the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor, daclatasvir, and the nonstructural protein 3 protease inhibitor, asunaprevir, in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected null responders. Hepatology. 2012;55:742–748. doi: 10.1002/hep.24724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Porto AF, Tormey L, Lim JK. Management of chronic hepatitis C infection in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:113–120. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834eb73f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]