Abstract

The activation of innate and adaptive immune signaling pathways and effector functions often occur at cellular membranes and are regulated by complex mechanisms. Here we review the growing number of proteins known to be regulated by S-palmitoylation in immune cells emerging from recent advances in chemical proteomics. These chemical proteomic studies have highlighted the roles of this dynamic lipid modification in regulating the specificity and strength of immune responses in different lymphocyte populations.

Introduction

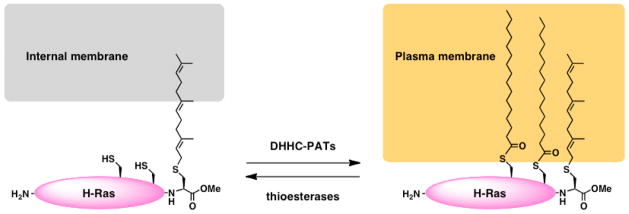

S-Palmitoylation is a reversible lipid post-translational modification that occurs on proteins in diverse cell types including lymphocytes that are crucial for the innate and adaptive immune responses. This covalent attachment of the 16-carbon palmitic acid to specific cysteine side chains regulates protein trafficking to membrane compartments in numerous biological processes [1,2]. For example, reversible S-palmitoylation of the small GTPases H- and N-Ras controls their plasma membrane versus Golgi localization and subsequent interaction with signaling partners that regulate cell growth and differentiation [3,4] (Figure 1). This cyclical control of S-palmitoylation is enzymatically mediated by a family of 23 mammalian DHHC motif-containing protein acyl transferases (DHHC-PATs) that catalyze S-palmitoylation [5–7], while the mechanisms and enzymes responsible for depalmitoylation remain enigmatic (See Martin BR review in this Issue). S-palmitoylation is known to recruit multiple key signaling molecules to the immunological synapse in T cells [8] and S-palmitoylated proteins in other lymphocyte populations are emerging with the advent of new technologies (Table 1). Herein, we describe the technical advances that have enabled improved detection and chemical proteomic analysis of S-palmitoylated proteins, and review the emerging roles of protein S-palmitoylation in the immune system that are being revealed through application of these chemical approaches.

Figure 1. Dynamic S-palmitoylation of H-Ras.

H-Ras is irreversibly prenylated at its C-terminus followed by cycles of S-palmitoylation and depalmitoylation that are mediated by DHHC-PATs and thioesterases, respectively. Prenylation of H-Ras targets the protein to internal organelle membranes while the addition of S-palmitoylation targets H-Ras to the plasma membrane.

Table 1. S-palmitoylated proteins in lymphocytes.

Examples of S-palmitoylated proteins that are either important for the function of the indicated lymphocyte populations or were discovered to be palmitoylated in a chemical proteomic study on the indicated cell type are shown. Examples include proteins that were classically identified on a candidate basis using H3-palmitate, as well as proteins that have been more recently identified in chemical proteomic screens using ABE and/or alk-16/ODYA.

| Cell type | Protein | Method of study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| T cells | FYN | 3H-Palmitate | 22 |

| LCK | 3H-Palmitate | 23,24 | |

| LAT | 3H-Palmitate | 25 | |

| CD4 | 3H-Palmitate | 26 | |

| CD8 | 3H-Palmitate | 27 | |

| FAM108B1 | alk-16/ODYA | 12 | |

| Histone H3 | alk-16/ODYA | 14 | |

| Dendritic cells | MHC class I | 3H-Palmitate | 40 |

| Invariant chain | 3H-Palmitate | 41 | |

| IFITM3 | alk-16/ODYA | 13 | |

| Macrophages | STX7 | 3H-Palmitate | 56 |

| SNAP-23 | 3H-Palmitate | 57 | |

| PLSCR3 | ABE and H3-Palmitate | 18 | |

| B cells | CD81 | 3H-Palmitate | 64 |

| CD20 | ABE and alk-16/ODYA | 65 | |

| CD23 | ABE and alk-16/ODYA | 65 |

Chemical Technologies for Studying S-Palmitoylation

S-Palmitoylation of the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Glycoprotein (VSV-G) was first described in 1979 when it was discovered that purified VSV-G contained a lipid species that could not be removed by organic extraction or protein denaturation and digestion [9]. This lipid was identified as palmitic acid and its incorporation into VSV-G was confirmed using radiolabeled 3H-palmititate [9]. Removal of the lipid with the thioester bond cleaving agent, hydroxylamine, suggested that the lipid modification occurred on a cysteine residue [9]. Demonstrating the incorporation of radiolabeled palmitate into candidate proteins at specific cysteine residues remained a gold standard for defining S-palmitoylation for more than two decades. However, this notoriously cumbersome and insensitive radioactivity-based method has limited the study of S-palmitoylation. Furthermore, unlike other lipid modifications, there is no unique consensus motif for S-palmitoylation and accurate prediction of S-palmitoylation sites on proteins remains challenging.

Two complementary chemical approaches have circumvented these limitations and greatly facilitated the investigation of S-palmitoylation [10]. For example, metabolic labeling of cells with alkynyl palmitate (alk-16) also referred to as 17-octadecynoic acid (ODYA) followed by bioorthogonal chemical ligation of labeled cellular proteins with azide-bearing fluorophores allows robust detection of protein S-palmitoylation and mapping of S-palmitoylation sites [11,12] (Figure 2). Compared to days or weeks for autoradiography, improved fluorescent detection of S-palmitoylated proteins using alk-16/ODYA takes minutes. In addition, bioorthogonal ligation of alk-16/ODYA labeled proteins with affinity tags such as azide-functionalized biotin enables enrichment and identification of S-palmitoylated proteins by mass spectrometry-based proteomics [12–14]. A complementary technique known as acyl-biotin exchange (ABE) has also been employed in recent years for the large-scale characterization of S-palmitoylated proteins [15] (Figure 2). This method first requires capping of free cysteines with thiol-reactive reagents such as N-ethyl maleimide. Palmitic acid is subsequently removed from modified cysteines using hydroxylamine, which cleaves thioester bonds, leaving the previously S-palmitoylated cysteines available for reaction with a thiol-reactive biotin moiety for affinity enrichment followed by identification. In fact, the analyses of S-palmitoyl-proteomes using the ABE method strongly suggest that the scope and functional contribution of this modification in eukaryotes has been largely underestimated [16,17]. For these methods, selectively cleavable reagents and/or high-content proteomics methods were particularly useful for profiling S-palmitoylomes [12–14,18]. Both the bioorthogonal labeling and ABE protocols have been successfully used in yeast and mammalian systems, revealing numerous new S-palmitoylated proteins that were not predicted by existing algorithms [19], including immunity-associated proteins that are the focus of this review.

Figure 2. Chemical methods for the study of S-palmitoylation.

(A) Metabolic labeling of cells with the alkynyl-palmitate reporter, alk-16/ODYA, allows incorporation of reporter onto proteins at sites of S-palmitoylation. Labeled proteins are reacted with azido-modified fluorescent or affinity tags via the copper catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction commonly referred to as “click chemistry.” This method allows robust fluorescent visualization or affinity enrichment and identification of S-palmitoylated proteins. (B) The ABE method requires capping of free cysteines with thiol-reactive reagents such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) followed by removal of S-palmitoylation with NH2OH. Exposed cysteines on previously palmitoylated proteins are then reacted with a thiol-reactive biotin analogue. Streptavidin blotting can be performed to visualize S-palmitoylated proteins. Alternatively, affinity enrichment of the biotin-labeled proteins can be performed for identification of S-palmitoylated proteins.

T cells

T lymphocytes play a primary role in cell-mediated immunity and exist as several distinct subtypes broadly grouped as cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cells or cytotoxic CD8+ T cells [20]. Engagement of the T cell receptor (TCR) by peptide/major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) on antigen presenting cells induces the activation and proliferation of T cells [21]. In this context, analysis of key proteins in T cell signaling has revealed an important role for S-palmitoylation in immunity [8]. For example, S-palmitoylation of signaling molecules such as Src family signaling kinases LCK [22,23] and FYN [24], transmembrane adaptor LAT (linker for activation of T cells) [25], and co-receptors CD4 [26] and CD8 [27] is required for effective TCR signaling [8]. Disruption of S-palmitoylation results in loss of membrane raft association by these proteins, concomitant with abrogation of TCR signaling [25,27–31]. Substitution of palmitate on LCK with a more hydrophilic oxygen-substituted palmitate analog that disrupts lipid packing also reduces raft association and weakens its signaling activity [32]. Although artificial targeting of chimeric LCK and LAT constructs to the plasma membrane without raft association restored their function in TCR signaling, their signaling properties are altered [33,34]. In addition, kinetics of palmitate turnover on LCK, which is accelerated upon T cell activation [35], is consistent with its cytosol-membrane exchange kinetics (~50 s) [36]. Together, these observations strongly indicate an important role for S-palmitoylation-mediated targeting to membrane microdomains in the modulation of TCR signaling.

Given the extensive characterization of S-palmitoylated proteins in T cells with 3H-palmitate, this cell type provided an excellent testing ground for the large-scale identification of S-palmitoylated proteins using the alk-16/ODYA palmitate reporter. Martin and Cravatt profiled alk-16/ODYA-labeled proteins from membrane fractions of Jurkat T cells, a human CD4+ T cell lymphoma line [12]. Validating the utility of the bioorthogonal labeling approach, T cell proteins known to be S-palmitoylated such as FYN, LCK, LAT, and CD4 were identified among more than 300 additional proteins, many of which, such as Ras isoforms, were also known to be S-palmitoylated in other cell types [12]. Also included in this list were novel S-palmitoylated proteins, such as the uncharacterized FAM108B1 serine hydrolase that mislocalizes when its cysteine-rich S-palmitoylated domain is deleted [12]. A complementary proteomic study of total cell lysates from alk-16/ODYA-labeled Jurkat T cells from our laboratory revealed a partially overlapping list of over 200 known and candidate S-palmitoylated proteins. The latter included histone H3 variants, which were found to be S-palmitoylated on cysteine 110 suggesting a novel potential role for this modification in histone H3 function [14]. The integration of stable isotope labeling by amino acids in T cell cultures with pulse-chase alk-16/ODYA proteomic studies has revealed distinct subsets of signaling proteins that are dynamically S-palmitoylated [37], suggesting that not all fatty-acylated proteins are subjected to temporal regulation like the Ras GTPases. These S-palmitoyl-proteomic data in T cells serve as a rich resource for further functional studies and paves the way for evaluating the role of S-palmitoylation in other cell types.

Dendritic cells

A defining feature of dendritic cells is their potent ability to present antigenic peptides on MHC class I and II molecules to T cells [38]. The site of engagement of MHC molecules on antigen presenting cells with the TCR is known as the immunological synapse [39]. While it is clear that S-palmitoylation controls recruitment of many T cell signaling molecules to the synapse membrane, the role of S-palmitoylation in forming and maintaining the antigen presenting cell side of the synapse is less appreciated. Even so, some MHC molecules themselves and other antigen presentation-associated proteins, such as the MHC-associated invariant chain and tetraspanins, have been shown to be S-palmitoylated [40–42], lending credence to the hypothesis that S-palmitoylation is important at both sides of this cell-to-cell signaling interface. Furthermore, S-palmitoylation has been reported for several cell surface receptors responsible for antigen uptake or dendritic cell activation during virus infections such as CD36 [43,44] and the interferon α/β receptor [45–47], respectively.

In an initial attempt at profiling the S-palmitoyl-proteome of dendritic cells, our group identified 157 alk-16/ODYA-labeled proteins in the DC2.4 cell line [13]. A majority of the identified proteins were previously reported in other cell types, and included calnexin, transferrin receptor, mannose-6-phosphate receptor, N-Ras, G protein subunits, and the tetraspanin CD9. Additionally, several novel candidate S-palmitoylated proteins involved in immune responses were identified. In particular, S-palmitoylation of the interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) and that of other family members, IFITM1 and IFITM2, was confirmed [13]. Upon mapping the sites of IFITM3 to three membrane-proximal cysteines, it was discovered that S-palmitoylation controls IFITM3 to clustering in endoplasmic reticulum and endolysosomal membrane compartments, and is required for the full activity of IFITM3 in inhibiting influenza virus infection [13,48]. These studies nicely complemented a genome-wide RNA interference screen that also identified IFITM3 as an influenza virus antagonist [49], and IFITM3 loss-of-function studies in mice and humans [50,51]. While the precise mechanism of action for IFITM3 antiviral activity is still under investigation, additional studies have suggested that IFITM3 alters the endolysosomal membrane compartment through which the influenza virus normally trafficks [48,52,53], and is likely not a transmembrane protein, but rather an intramembrane protein whose complete targeting and association with membranes requires S-palmitoylation [48]. These early chemical proteomic studies have uncovered new S-palmitoylated proteins in dendritic cells and highlight an unappreciated role for S-palmitoylation in host defense against viral pathogens.

Macrophages

Macrophages serve as phagocytes in the immune system engulfing pathogens and cellular debris for digestion in lysosomal compartments [54]. Membrane remodeling involved in phagocytosis and other immunomodulatory functions of macrophages such as cytokine secretion are likely to involve S-palmitoylated proteins. Support for this hypothesis is provided by studies of syntaxin-7, an S-palmitoylated protein involved in macrophage phagocytosis [55,56], and SNAP-23, an S-palmitoylated membrane fusion protein involved in tumore necrosis factor alpha secretion [57,58]. Merrick and colleagues recently employed the ABE method to profile S-palmitoylated proteins in the murine RAW264.7 macrophage line [18]. This study proved fruitful in identifying 98 candidate proteins, 76% of which were previously suggested to be S-palmitoylated by other studies in mammalian cells including syntaxin-7 and SNAP-23. This significant overlap with the literature validated the methodology and suggested that the 24 novel candidates identified in this study are likely to be S-palmitoylated. These results also supported a role for S-palmitoylation in targeting proteins to lipid rafts as 48% of the identified proteins were also seen in a separate proteomic analysis of macrophage detergent-resistant membranes [18,59]. Among the novel candidate proteins without previous report of S-palmitoylation is LAT2, a non-T cell-specific homologue of LAT that participates in signaling cascades originating at the plasma membrane [60], though the S-palmitoylation of this molecule has yet to be followed up in terms of function. Phospholipid scramblase 3 (PLSCR3) was also identified in this study and its sites of S-palmitoylation were mapped to a cluster of five cysteines. An S-palmitoylation-deficient PLSCR3 mutant was mislocalized from the mitochondria to the nucleus, providing the first example of protein targeting to the mitochondria by S-palmitoylation [18]. Given the crucial role of the mitochondria in initiating programmed cell death, the authors examined the role of PLSCR3 in apoptosis. Interestingly, overexpression of PLSCR3 sensitized macrophages to etoposide-induced apoptosis, and this was largely dependent on PLSCR3 S-palmitoylation and mitochondrial localization [18]. Thus, S-palmitoylation plays a role in the pro-apoptotic function of PLSCR3 and our understanding of the role of S-palmitoylation in macrophage biology continues to expand.

B cells

The primary function of B cells is to recognize antigen through the B cell receptor (BCR) and subsequently produce and secrete antigen-specific antibodies [61]. These cells mediate the humoral immune response important for the opsonization and neutralization of pathogens [62]. B cells have long been recognized as a model system for studying the importance of tetraspanin-rich membrane microdomains characterized by the presence of numerous S-palmitoylated tetraspanin proteins that provide a structural framework for receptors to transmit signals to intracellular molecules [63]. In fact, S-palmitoylation of the tetraspanin CD81 is necessary for the stabilization of the CD19/CD21/CD81/BCR complex that leads to enhanced BCR signaling upon antigen binding [64]. Again, the example set by S-palmitoylation studies of tetraspanins and other B cell proteins using classical techniques primed an interest in large-scale analysis of B cell S-palmitoylation. Thus, Ivaldi and coworkers performed ABE and proteomics to identify S-palmitoylated proteins in a human B lymphoid cell line [65]. Of 95 putative S-palmitoylated proteins, 46 were distinct MHC isoforms and 39 were suggested by other proteomic studies or were previously confirmed on a candidate basis. These 39 proteins included tetraspanins CD81, CD9, CD63, and CD82, as well as IFITM1, N-Ras, and LCK. Of the 10 newly identified molecules, the immunoregulatory, B cell-specific CD20 molecule and CD23, which is important for B cell development, were validated by demonstrating alk-16/ODYA incorporation on specific cysteine residues [65]. Both of these molecules are important drug targets in human B cell disorders, such as lymphoma, underscoring the importance of defining the cell biology governing the action of these proteins [66,67]. Thus, the success of using these new chemical tools, both ABE and alk-16/ODYA, in B lymphocytes presents an exciting opportunity to continue to learn more about the control of B cell function and differentiation by S-palmitoylation.

Perspectives

The utility of the newly developed tools for studying S-palmitoylation has been demonstrated by the S-palmitoyl-proteomics studies reviewed here. Of the novel S-palmitoylated proteins that have been identified, only a limited number have been functionally characterized. In T cells the lymphocyte specific CD5 protein and the TCR delta chain (CD3δ), whose deficiency leads to severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome, were identified from S-palmitoyl-proteomics but not further characterized [12,14,37]. Given the essential nature of CD3δ in T cell development [68] and the presence of a conserved cysteine at the cytoplasmic edge of its transmembrane domain, it would be interesting to determine if CD3δ S-palmitoylation affects T cell function. Likewise, MHC molecules and other known S-palmitoylated proteins such as additional small GTPases and tetrapsanins were not identified in palmitoyl-proteome studies of DC2.4 cells [13], indicating that improvements in protein recovery and mass spectrometry techniques may yet increase our understanding of S-palmitoylation in dendritic cells and other lymphocyte subtypes. Improvements in sensitivity should afford new opportunities to compare S-palmitoylation in primary resting and activated lymphocyte populations in various developmental stages. Importantly, the key enzymes (DHHC-PATs and thioesterases) regulating the S-palmitoylation of specific proteins in lymphocyte subsets are largely unknown and represent a crucial area for future investigation. As protein S-palmitoylation controls interactions in cellular membranes, additional studies of this lipid-modification will continue to be important for understanding the strength and specificity of cell signaling events in innate and adaptive immunity.

Highlights.

The alk-16/ODYA chemical reporter and the acyl-biotin exchange methods for studying protein S-palmitoylation are presented.

The role of S-palmitoylation in the control of the immune response is highlighted.

Recent S-palmitoyl proteome studies performed in T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and B cells using new chemical proteomic methods are reviewed.

Acknowledgments

J.S.Y acknowledges support from NIH/NIAID (1K99AI095348). M. M. Z. is supported by A*STAR, Singapore. H.C.H. acknowledges support from Ellison Medical Foundation and NIH/NIGMS (1R01GM087544).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fukata Y, Fukata M. Protein palmitoylation in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(3):161–175. doi: 10.1038/nrn2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Palmitoylation: Policing protein stability and traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(1):74–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magee AI, Gutierrez L, McKay IA, Marshall CJ, Hall A. Dynamic fatty acylation of p21n-ras. The EMBO journal. 1987;6(11):3353–3357. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *4.Rocks O, Peyker A, Kahms M, Verveer PJ, Koerner C, Lumbierres M, Kuhlmann J, Waldmann H, Wittinghofer A, Bastiaens PI. An acylation cycle regulates localization and activity of palmitoylated ras isoforms. Science. 2005;307(5716):1746–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1105654. This study first demonstrated that reversible S-palmitoylation is crucial for ras localization and function by comparing semi-synthetic ras isoforms with a thioester linked palmitate versus non-hydrolyzable ether linked variant. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lobo S, Greentree WK, Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Identification of a ras palmitoyltransferase in saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(43):41268–41273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth AF, Feng Y, Chen L, Davis NG. The yeast dhhc cysteine-rich domain protein akr1p is a palmitoyl transferase. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(1):23–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korycka J, Lach A, Heger E, Boguslawska DM, Wolny M, Toporkiewicz M, Augoff K, Korzeniewski J, Sikorski AF. Human dhhc proteins: A spotlight on the hidden player of palmitoylation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resh MD. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE. 2006;2006(359):re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **9.Schmidt MF, Schlesinger MJ. Fatty acid binding to vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein: A new type of post-translational modification of the viral glycoprotein. Cell. 1979;17(4):813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90321-0. This study was the first to describe protein S-palmitoylation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hang HC, Wilson JP, Charron G. Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for analyzing protein lipidation and lipid trafficking. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(9):699–708. doi: 10.1021/ar200063v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *11.Charron G, Zhang MM, Yount JS, Wilson J, Raghavan AS, Shamir E, Hang HC. Robust fluorescent detection of protein fatty-acylation with chemical reporters. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(13):4967–4975. doi: 10.1021/ja810122f. This study describes the direct fluorescence detection of alkynyl-fatty acid labeled proteins in mammalian cells following bioorthogonal labeling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **12.Martin BR, Cravatt BF. Large-scale profiling of protein palmitoylation in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2009;6(2):135–138. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1293. This study describes the fluorescence detection and proteomic identification of alkynyl-fatty acid labeled proteins in Jurkat T cells following bioorthogonal labeling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **13.Yount JS, Moltedo B, Yang YY, Charron G, Moran TM, Lopez CB, Hang HC. Palmitoylome profiling reveals s-palmitoylation-dependent antiviral activity of ifitm3. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(8):610–614. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.405. This study describes the bioorthogonal proteomic identification of S-palmitoylated proteins in a dendritic cell line and the characterization of IFITM3 S-palmitoylation and antiviral activity against influenza virus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Wilson JP, Raghavan AS, Yang YY, Charron G, Hang HC. Proteomic analysis of fatty-acylated proteins in mammalian cells with chemical reporters reveals s-acylation of histone h3 variants. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(3):M110 001198. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001198. This study describes the bioorthogonal proteomic identification of alkynyl-fatty acid labeled proteins in Jurkat T cells and the charcterization of histone H3 S-acylation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan J, Roth AF, Bailey AO, Davis NG. Palmitoylated proteins: Purification and identification. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(7):1573–1584. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *16.Roth AF, Wan J, Bailey AO, Sun B, Kuchar JA, Green WN, Phinney BS, Yates JR, 3rd, Davis NG. Global analysis of protein palmitoylation in yeast. Cell. 2006;125(5):1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.042. This study describes the first proteomic identification of S-acylated proteins proteins in budding yeast using the acyl-biotin exchange method. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **17.Kang R, Wan J, Arstikaitis P, Takahashi H, Huang K, Bailey AO, Thompson JX, Roth AF, Drisdel RC, Mastro R, Green WN, et al. Neural palmitoyl-proteomics reveals dynamic synaptic palmitoylation. Nature. 2008;456(7224):904–909. doi: 10.1038/nature07605. This study describes the proteomic identification of S-acylated proteins in neurons using the acyl-biotin exchange method and the discovery of S-palmitoylation on the Cdc42 brain-isoform. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **18.Merrick BA, Dhungana S, Williams JG, Aloor JJ, Peddada S, Tomer KB, Fessler MB. Proteomic profiling of s-acylated macrophage proteins identifies a role for palmitoylation in mitochondrial targeting of phospholipid scramblase 3. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(10):M110 006007. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.006007. This study describes the proteomic identification of S-acylated proteins in a macrophage cell line using the acyl-biotin exchange method and the characterization of phospholipid scramblase 3 S-palmitoylation-dependent targeting to the mitochondria. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren J, Wen L, Gao X, Jin C, Xue Y, Yao X. Css-palm 2.0: An updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2008;21(11):639–644. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong Y, Bosselut R. Cd4–cd8 differentiation in the thymus: Connecting circuits and building memories. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fooksman DR, Vardhana S, Vasiliver-Shamis G, Liese J, Blair DA, Waite J, Sacristan C, Victora GD, Zanin-Zhorov A, Dustin ML. Functional anatomy of t cell activation and synapse formation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenoy-Scaria AM, Gauen LK, Kwong J, Shaw AS, Lublin DM. Palmitylation of an amino-terminal cysteine motif of protein tyrosine kinases p56lck and p59fyn mediates interaction with glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(10):6385–6392. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paige LA, Nadler MJ, Harrison ML, Cassady JM, Geahlen RL. Reversible palmitoylation of the protein- tyrosine kinase p56lck. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(12):8669–8674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenoy-Scaria AM, Dietzen DJ, Kwong J, Link DC, Lublin DM. Cysteine3 of src family protein tyrosine kinase determines palmitoylation and localization in caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1994;126(2):353–363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W, Trible RP, Samelson LE. Lat palmitoylation: Its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during t cell activation. Immunity. 1998;9(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crise B, Rose JK. Identification of palmitoylation sites on cd4, the human immunodeficiency virus receptor. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(19):13593–13597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arcaro A, Gregoire C, Boucheron N, Stotz S, Palmer E, Malissen B, Luescher IF. Essential role of cd8 palmitoylation in cd8 coreceptor function. J Immunol. 2000;165(4):2068–2076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang X, Nazarian A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Bornmann W, Tempst P, Resh MD. Heterogeneous fatty acylation of src family kinases with polyunsaturated fatty acids regulates raft localization and signal transduction. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(33):30987–30994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hundt M, Tabata H, Jeon MS, Hayashi K, Tanaka Y, Krishna R, De Giorgio L, Liu YC, Fukata M, Altman A. Impaired activation and localization of lat in anergic t cells as a consequence of a selective palmitoylation defect. Immunity. 2006;24(5):513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb Y, Hermida-Matsumoto L, Resh MD. Inhibition of protein palmitoylation, raft localization, and t cell signaling by 2-bromopalmitate and polyunsaturated fatty acids. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(1):261–270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balamuth F, Brogdon JL, Bottomly K. Cd4 raft association and signaling regulate molecular clustering at the immunological synapse site. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):5887–5892. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawash IY, Hu XE, Adal A, Cassady JM, Geahlen RL, Harrison ML. The oxygen-substituted palmitic acid analogue, 13-oxypalmitic acid, inhibits lck localization to lipid rafts and t cell signaling. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2002;1589(2):140–150. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabouridis PS, Magee AI, Ley SC. S-acylation of lck protein tyrosine kinase is essential for its signalling function in t lymphocytes. The EMBO journal. 1997;16(16):4983–4998. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otahal P, Angelisova P, Hrdinka M, Brdicka T, Novak P, Drbal K, Horejsi V. A new type of membrane raft-like microdomains and their possible involvement in tcr signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3689–3696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *35.Zhang MM, Tsou LK, Charron G, Raghavan AS, Hang HC. Tandem fluorescence imaging of dynamic s- acylation and protein turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(19):8627–8632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912306107. This study describes the dual metabolic labeling of newly synthesized and S-acylated proteins with chemical reporters, which can be used to monitor protein and lipid turnover in cells. This method revealed accelerated S-acylation dynamics on signaling kinases such as Lck during T cells activation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann L, Paster W, Weghuber J, Eckerstorfer P, Stockinger H, Schutz GJ. Direct observation and quantitative analysis of lck exchange between plasma membrane and cytosol in living t cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285(9):6063–6070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Martin BR, Wang C, Adibekian A, Tully SE, Cravatt BF. Global profiling of dynamic protein palmitoylation. Nat Methods. 2012;9(1):84–89. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1769. This study describes the large-scale proteomic analysis of dynamic S-acylation in T cells, which revealed accelerated lipid turnover on signaling molecules compared to other abundant membrane-associated S-palmitoylated proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449(7161):419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dustin ML, Depoil D. New insights into the t cell synapse from single molecule techniques. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(10):672–684. doi: 10.1038/nri3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruda R, Achdout H, Stern-Ginossar N, Gazit R, Betser-Cohen G, Manaster I, Katz G, Gonen-Gross T, Tirosh B, Mandelboim O. Intracellular cysteine residues in the tail of mhc class i proteins are crucial for extracellular recognition by leukocyte ig-like receptor 1. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):3655–3661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch N, Hammerling GJ. The hla-d-associated invariant chain binds palmitic acid at the cysteine adjacent to the membrane segment. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(7):3434–3440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang X, Claas C, Kraeft SK, Chen LB, Wang Z, Kreidberg JA, Hemler ME. Palmitoylation of tetraspanin proteins: Modulation of cd151 lateral interactions, subcellular distribution, and integrin-dependent cell morphology. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(3):767–781. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tao NB, Wagner SJ, Lublin DM. Cd36 is palmitoylated on both n- and c-terminal cytoplasmic tails. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(37):22315–22320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urban BC, Willcox N, Roberts DJ. A role for cd36 in the regulation of dendritic cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8750–8755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151028698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Claudinon J, Gonnord P, Beslard E, Marchetti M, Mitchell K, Boularan C, Johannes L, Eid P, Lamaze C. Palmitoylation of interferon-alpha (ifn-alpha) receptor subunit ifnar1 is required for the activation of stat1 and stat2 by ifn-alpha. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(36):24328–24340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yount JS, Moran TM, Lopez CB. Cytokine-independent upregulation of mda5 in viral infection. J Virol. 2007;81(13):7316–7319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00545-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yount JS, Gitlin L, Moran TM, Lopez CB. Mda5 participates in the detection of paramyxovirus infection and is essential for the early activation of dendritic cells in response to sendai virus defective interfering particles. J Immunol. 2008;180(7):4910–4918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yount JS, Karssemeijer RA, Hang HC. S-palmitoylation and ubiquitination differentially regulate interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (ifitm3)-mediated resistance to influenza virus. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, Adams DJ, et al. The ifitm proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza a h1n1 virus, west nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139(7):1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Everitt AR, Clare S, Pertel T, John SP, Wash RS, Smith SE, Chin CR, Feeley EM, Sims JS, Adams DJ, Wise HM, et al. Ifitm3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature. 2012;484(7395):519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bailey CC, Huang IC, Kam C, Farzan M. Ifitm3 limits the severity of acute influenza in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(9):e1002909. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feeley EM, Sims JS, John SP, Chin CR, Pertel T, Chen LM, Gaiha GD, Ryan BJ, Donis RO, Elledge SJ, Brass AL. Ifitm3 inhibits influenza a virus infection by preventing cytosolic entry. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(10):e1002337. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang IC, Bailey CC, Weyer JL, Radoshitzky SR, Becker MM, Chiang JJ, Brass AL, Ahmed AA, Chi X, Dong L, Longobardi LE, et al. Distinct patterns of ifitm-mediated restriction of filoviruses, sars coronavirus, and influenza a virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(1):e1001258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11(11):723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collins RF, Schreiber AD, Grinstein S, Trimble WS. Syntaxins 13 and 7 function at distinct steps during phagocytosis. J Immunol. 2002;169(6):3250–3256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He YH, Linder ME. Differential palmitoylation of the endosomal snares syntaxin 7 and syntaxin 8. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(3):398–404. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800360-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogel K, Roche PA. Snap-23 and snap-25 are palmitoylated in vivo. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1999;258(2):407–410. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lacy P, Stow JL. Cytokine release from innate immune cells: Association with diverse membrane trafficking pathways. Blood. 2011;118(1):9–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-265892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dhungana S, Merrick BA, Tomer KB, Fessler MB. Quantitative proteomics analysis of macrophage rafts reveals compartmentalized activation of the proteasome and of proteasome-mediated erk activation in response to lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(1):201–213. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800286-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orr SJ, McVicar DW. Lab/ntal/lat2: A force to be reckoned with in all leukocytes? J Leukocyte Biol. 2011;89(1):11–19. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0410221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidlin H, Diehl SA, Blom B. New insights into the regulation of human b-cell differentiation. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(6):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaur K, Sullivan M, Wilson PC. Targeting b cell responses in universal influenza vaccine design. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(11):524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Spriel AB. Tetraspanins in the humoral immune response. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39(2):512–517. doi: 10.1042/BST0390512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cherukuri A, Carter RH, Brooks S, Bornmann W, Finn R, Dowd CS, Pierce SK. B cell signaling is regulated by induced palmitoylation of cd81. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(30):31973–31982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *65.Ivaldi C, Martin BR, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Chapel A, Levade T, Garin J, Journet A. Proteomic analysis of s-acylated proteins in human b cells reveals palmitoylation of the immune regulators cd20 and cd23. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037187. This study describes the proteomic identification of S-acylated proteins in B cells using the acyl-biotin exchange method as well as validation of CD20 and CD23 S-palmitoylation with an alkynyl palmitate chemical reporter. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barcellini W, Zanella A. Rituximab therapy for autoimmune haematological diseases. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(3):220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenwasser LJ, Meng JF. Anti-cd23. Clin Rev Allerg Immu. 2005;29(1):61–72. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:29:1:061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Saint Basile G, Geissmann F, Flori E, Uring-Lambert B, Soudais C, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Durandy A, Jabado N, Fischer A, Le Deist F. Severe combined immunodeficiency caused by deficiency in either the delta or the epsilon subunit of cd3. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(10):1512–1517. doi: 10.1172/JCI22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]