Abstract

This study examined the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and the presence of anxiety and depression in a sample of low-income urban dwelling whites. Data were analyzed from a cross-sectional survey of low-income whites living in an inner-city neighborhood in the mid-Atlantic United States. Perceived racial discrimination was reported by 39 percent of participants. Rates of depression in the population exceed prevalence rates in the general U.S. population. Those who perceived racial discrimination and were bothered by it experienced significantly greater odds of being depressed (OR = 2.78, 95% CI: 1.60 – 4.82) and had higher anxiety scores (b=2.02, SE: 0.55, p=0.000) than those who did not perceive racial discrimination. Low-income urban white populations have been largely ignored in public health research. This study demonstrates that perceived racial discrimination is common in poor urban whites. Further, exposure to discrimination which is perceived as a stressor is associated with mental illness.

Keywords: Racial discrimination, mental illness, depression, anxiety, residential segregation, urban, whites, low-income

Introduction

Unfair treatment resulting from discrimination (racial/ethnic, gender, sexual orientation) has been studied as a predictor of health outcomes since the early 1980s. A majority of these studies examined racial/ethnic discrimination and mental health outcomes (1). In addition, mental health outcomes have demonstrated the “strongest and most consistent association” with discrimination. Psychological distress and well-being (e.g. – life satisfaction, happiness) have been the two most commonly studied mental health outcomes, with a majority of these studies demonstrating a positive association whereby exposure to discrimination is associated with worst mental health status (1). Fewer studies have examined the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental illness, such as depression and anxiety. However, those studies that have, consistently demonstrate an association between discrimination and depression (2-9). Anxiety has been measured as an outcome in fewer studies, but in most it has been found to be positively associated with racial discrimination (2-4).

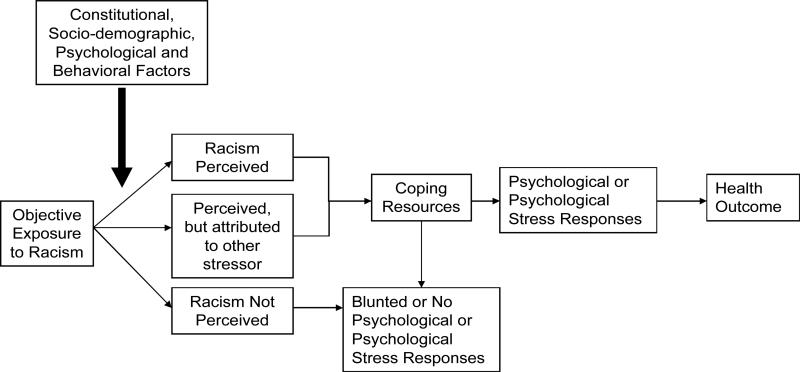

Racism is related but distinct from racial discrimination. Clark and colleagues (10) defined racism as “beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that tend to denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics or ethnic group affiliation.” Whereas, racial discrimination refers to the behavioral aspects of racism, “practices ranging from social distancing to aggression” (11). Attitudes and acts of racism can be held or perpetuated by those of a different ethnic group (intergroup racism) or by members of the same ethnic group (intragroup racism). A model depicting the biopsychosocial factors and pathways involved between the experience of perceived discrimination and ill-health is presented by Clark and colleagues (10) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Racism 29

The Clark (11) model is based on Lazarus and Folkman's (12) stress and coping model. It asserts that environmental stimuli lead to a perception of discrimination, which is mediated by the individual's coping and psychological/physiological responses and ultimately results in a health outcome. Acute or chronic exposures to institutional policies or interpersonal interactions are the stressors thought to act as the environmental stimuli triggering this sequence of events. Moderator variables may influence the magnitude of the relationship between the stimuli and a person's perception of discrimination. These moderators include “constitutional factors” such as family history and skin tone; sociodemographic factors such as socioeconomic status, age, and gender; and psychological; and behavioral factors such as type A behavior and self-esteem. If the experience is not perceived as a stressor, there is no resulting psychological or physiological response. However, if the experience is perceived as a stressor, this perception is mediated by the individual's coping response and is either blunted, ending the chain of events, or it results in a psychological response such as anxiety, anger, and hopelessness or a physiological response involving immune, neuroendocrine, or cardiovascular functioning. In turn, ill-health outcomes, such as depression, hypertension or heart disease, can occur.

Although these definitions and the conceptual model have been applied primarily to ethnic minorities, especially African Americans, they do not preclude application to a white population (10). All ethnicities, including whites, are susceptible to intergroup and intragroup conflict and any individual can attribute such events to racial discrimination. And, regardless of race, experiences of discrimination may result in negative health consequences for all individuals.

Although African Americans experience racial discrimination more frequently and with greater intensity than whites (4, 13, 14), there have been mixed results as to whether blacks or whites experience worse health outcomes as a result. Several studies have found that the negative effect of discrimination may actually be greater among whites (13, 15-17). Whites may be more affected by discrimination than African Americans. It may be the case that the coping response in whites is not as well developed as it is in African Americans, resulting in a greater adverse reaction to perceived racial discrimination as a stressor.

Another recent study found a positive association between perceived discrimination and depression in a low-income sample. However, the sample was primarily female, not necessarily urban dwelling, and discrimination was defined more broadly so that it was not specific to experiences of racial discrimination. We were unable to find any previous studies that examined the association between perceived racial discrimination and health in a low-income urban-dwelling white sample. This subpopulation is unique in that it is experiencing living conditions stereotypically associated with low-income urban dwelling African Americans. It is not known if perceived racial discrimination would have an effect on depression and anxiety in this population. This study aims to characterize the prevalence of perceived racial discrimination in a low-income white population living in an inner-city neighborhood in a large mid-Atlantic U.S. city and to explore the associations of perceived racial discrimination with anxiety and depression in this population.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design and Population

Exploring Health Disparities in Integrated Communities (EHDIC) is a multisite study of health disparities within racially integrated communities without racial disparities in income. The study site of Southwest Baltimore (SWB) was a cross-sectional, face-to-face survey of the adult population (age 18 and older) of two contiguous, census tracts where the racial distribution was 51 percent African American and 44 percent white. The median income for the study area was $24,002 and the 20.3% of the residents were high school graduates. Approximately 40 percent of the adult residents in the study area were enrolled into the study (n=1,489). Respondents completed a structured questionnaire, all of which were administered by trained personnel. The EHDIC-SWB study is described in greater detail elsewhere (18). The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and all participants gave informed consent. For this analysis we examined the subset of respondents who self-reported as non-Hispanic white and had complete data on the dependent variables (n=573).

Measures

Perceived racial discrimination

Perceived racial discrimination was measured using the Experiences of Discrimination scale (EOD), an instrument developed by Krieger and Sidney (19) that has been found to have good reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.77) and construct validity (20). Participants reported whether they had “ever experienced discrimination, been prevented from doing something, or been hassled or made to feel inferior because of their race or color in any of the following settings: at school; getting a job; at work; getting housing; getting medical care; from the police or in the courts; and at a store, restaurant, or some other place (21).” We summed the number of settings a respondent experienced racial discrimination and classified them into three categories (none, 1-2, >2). For each setting that a respondent experienced racial discrimination, they reported how much it bothered them (not at all, a little, or a lot). A racial discrimination variable was constructed as a three level variable with the following categories: (a) no discrimination experienced, (b) discrimination experienced and it either didn’t bother the respondent or bothered them a little, and (c) discrimination experienced and it bothered them a lot. The Cronbach's alpha for this variable was 0.83.

Mental Illness

Depression was evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) (22). The PHQ uses a Likert-type scale with four possible responses (1=not at all, 2=several days, 3=more than half the days, 4=nearly every day). Answering “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” on 4 or more of the questions (including at least one of two questions: “little interest or pleasure in doing things” or “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”) was classified as having depressive syndrome. Answering “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” on 5 or more of the questions (including at least one of two questions: “little interest or pleasure in doing things” or “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”) was categorized as having major depression. Participants identified as having either depressive syndrome or major depression were combined to create one dichotomous depression variable that was used in the logistic regression models.

Anxiety was evaluated using the anxiety subscale of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), which consists of a 7-item scale (23). Responses to the seven questions were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1=not at all, 2=no more than usual, 3=rather more than usual, and 4=much more than usual). No formal cut-point has been established for the GHQ anxiety subscale; therefore, we assessed it as a continuous variable with a higher score indicating a higher anxiety score (range: 7 to 28).

Sociodemographic Variables

The sociodemographic variables included age, gender, education, marital status, income, and employment status. Gender was dichotomized with one representing females and zero representing males. Educational status consisted of three binary variables: less than high school, high school graduate or GED, and some college to graduate degree. Marital status consisted of four binary variables: married or living as married, widowed, divorced or separated, and never been married. Employment status consisted of four binary variables: working full-time or part-time, unemployed, retired or disabled, and attending school or maintaining the home. Age and household income were evaluated as continuous variables.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses included means (standard deviations) and frequencies to summarize continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Multiple logistic regression was used to determine the association between perceived discrimination and depression, adjusting for sociodemographic variables (gender, age, and marital status, income, education, employment status). Multiple linear regression was used to evaluate the association between perceived discrimination and anxiety, adjusting for the sociodemographic variables. Any p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and all tests were two-sided. All analyses used STATA 9.0 statistical software (STATA Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Population Characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. Of the 573 participants, 56.9 percent were female, approximately one quarter (25.7%) were married or living as married, and the mean age was 44 years. Almost half of the respondents (47.5%) reported less than a high school education, 37 percent were employed full- or part-time, and the average annual income was $24,816. Mental health indicators are also presented in Table 1. A total of 15 percent of participants were identified as having depression (12.2% met the criteria for major depression). The mean anxiety score was 12.3 (sd = 5.8), with a median score of 10.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Outcome Indicators: White Participants in the EHDIC Study (n = 573)

| Total N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Socidemographics | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 247 (43.1) |

| Female | 326 (56.9) |

| Age in years | |

| 18 – 24 | 74 (12.2) |

| 25 – 34 | 106 (18.5) |

| 35 – 44 | 137 (23.9) |

| 45 – 54 | 113 (19.7) |

| ≥55 | 143 (25.0) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married or living as married | 147 (25.7) |

| Widowed | 62 (10.8) |

| Divorced or separated | 151 (26.4) |

| Never married | 212 (37.1) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 272 (47.5) |

| High school graduate or GED | 196 (34.2) |

| Some college to graduate degree | 105 (18.3) |

| Annual Income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 127 (22.2) |

| $10,000 - $24,999 | 231 (40.3) |

| $25,000 - $50,000 | 148 (25.8) |

| More than $50,000 | 67 (11.7) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed full or part-time | 210 (37.2) |

| Unemployed | 147 (26.0) |

| Retired or disabled | 176 (31.2) |

| Attending school or maintaining the home | 32 (5.6) |

| Outcomes | |

| Depression | |

| No | 485 (84.6) |

| Yes | 88 (15.4) |

| Anxiety, mean (sd) | 12.3 (5.8) |

Perceived Racial Discrimination

The frequency of reported settings where racial discrimination was experienced is displayed in Table 2. In response to questions about experience of unfair treatment because of race, 61.1 percent responded “no” to ever having experienced racial discrimination in any of the seven settings described. Of these white respondents, 31 percent perceived racial discrimination in one or two of the settings and 8 percent reported experiencing discrimination in three or more settings. The setting with the largest report of racial discrimination was related to the police or the courts (15.9%). There were 13 percent of respondents who perceived racial discrimination but were either not bothered or bothered a little, while 26 percent of respondents perceived racial discrimination and were bothered a lot.

Table 2.

Frequency of Perceived Discrimination in White EHDIC Participants (n = 573)

| Total N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Number of settings where racial discrimination experienced | |

| None | 350 (61.1) |

| 1-2 settings | 177 (30.9) |

| More than 2 settings | 46 (8.0) |

| Racial discrimination | |

| At school | 80 (14.0) |

| Getting a job | 50 (8.7) |

| At work | 58 (10.2) |

| Getting housing | 28 (4.9) |

| Getting medical care | 34 (6.0) |

| From police or in courts | 90 (15.9) |

| At a store, restaurant, or other | 56 (9.8) |

| Bothered by racial discrimination | |

| No discrimination reported | 349 (61.0) |

| Discrimination and bothered not at all or a little | 74 (12.9) |

| Discrimination and bothered a lot | 149 (26.1) |

Mental Health in Relation to Perceived Racial Discrimination

The odds ratio (OR) and 95 percent confidence interval (CI) generated from the multiple logistic regressions models for the association between perceived racial discrimination and depression are displayed in Table 3. In the unadjusted model, those who perceived racial discrimination and were ‘bothered a lot’ had 2.6 (95% CI 1.59 – 4.21) times greater odds of being depressed compared to those who did not perceive racial discrimination. In the adjusted model, those who perceived racial discrimination and were ‘bothered a lot’ had 2.8 (95% CI 1.60 – 4.82) times greater odds of being depressed compared to those who did not perceive racial discrimination. There was no difference in the odds of depression between those who did not perceive racial discrimination and those who perceived racial discrimination but where ‘not bothered’ or ‘bothered a little’ (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.38 – 2.27). In the adjusted model, employment status was the only sociodemographic characteristics found to be significantly associated with depression. Those who were unemployed, retired, or disabled were found to have significantly greater odds of being depressed when compared to individuals who were employed full or part-time.

Table 3.

Associations between Mental Health Indicators and Perceived Racial Discrimination in the 573 White EHDIC Participantsa

| Variable | Unadjusted Model Depression OR (95% CI) | Adjusted Modelb Depression OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted Model Anxiety b (SE) | Adjusted Model Anxiety b(SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bothered by discrimination | ||||

| No discrimination | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Not bothered/bothered a little | 0.76 (0.33 – 1.77) | 0.93 (.38 – 2.27) | 0.05 (0.74) | 0.12 (0.71) |

| Bothered a lot | 2.59** (1.59 – 4.22) | 2.78** (1.60 – 4.82) | 2.42** (0.56) | 2.02** (0.55) |

| Age | 0.99 (.97 – 1.01) | −0.07** (0.12) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 0.72 (.42 – 1.23) | −1.37** (0.49) | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| Less than high school grad | reference | Reference | ||

| High school graduate / GED | 0.69 (.39 – 1.22) | −0.20 (0.53) | ||

| Some college to graduate degree | 0.58 (.24 – 1.43) | −0.15 (0.71) | ||

| Income | ||||

| <$10,000 | reference | reference | ||

| $10,000 - $24,999 | 0.69 (.39 – 1.23) | −1.84** (0.62) | ||

| $25,000 - $50,000 | 0.47 (.20 – 1.07) | −2.22** (0.74) | ||

| >$50,000 | 0.66 (.20 – 2.15) | −2.59** (0.97) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married or living as married | reference | Reference | ||

| Widowed | 0.99 (.40 – 2.52) | −0.86 (0.93) | ||

| Divorced or separated | 1.05 (.50 – 1.90) | 0.22 (0.66) | ||

| Never married | 0.52 (.24 – 1.02) | −0.63 (0.64) | ||

| Employment Status | ||||

| Employed full or part- time | reference | reference | ||

| Unemployed | 2.30*(1.07 – 4.94) | 1.22* (0.62) | ||

| Retired or disabled | 3.82** (1.72 – 8.50) | 3.03** (0.71) | ||

| Attending school or maintaining the home | 0.65 (.13 – 3.21) | −1.73 (1.08) | ||

| Constant | 11.66 (0.31) | 16.32 (1.22) |

The depression variable was a dichotomous variable; therefore, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented. Anxiety scores were considered to be a continuous variable; therefore, beta coefficients and standard errors are presented.

Adjusted model controlled for: age, gender, marital status, annual income, employment status

indicates a p-value <0.01

indicates a p-value <0.05

Table 3 also displays the unadjusted and adjusted multiple linear regression models for the association between perceived racial discrimination and anxiety scores. In the unadjusted model, those who experienced discrimination and were ‘bothered a lot’ had higher anxiety scores (b = 2.42, SE 0.56, p < 0.01) than those who did not experience discrimination. This relationship remained significant after adjusting for age, gender, marital status, annual income, and employment status, those who experienced racial discrimination and were ‘bothered a lot’ scored an average of 2.02 (SE 0.55, p < 0.01) points higher on the anxiety scale than those who did not experience discrimination. In contrast, those who experienced discrimination but where “not bothered at all’ or ‘bothered a little,’ did not score higher on the anxiety scale in the adjusted model (b = 0.12, SE: 0.71, p = 0.87). In the adjusted model, several of the sociodemographic characteristics were significantly associated with anxiety. Older individual had lower anxiety scores than younger individuals. Females experienced significantly higher anxiety scores compared to males and higher income individuals were found to have significantly lower anxiety scores when compared to those in the lowest income category. Employment status is significantly associated with anxiety; those who are unemployed, retired, or disabled are found to have significantly higher rates of both depression and anxiety when compared to individuals who are employed full or part-time.

Discussion

In this low-income urban white sample, we found evidence of an association between perceived racial discrimination and depression and anxiety. This study illustrates exposure to discrimination that is perceived as a stressor is positively associated with depression and anxiety. Poor whites living in inner city neighborhoods are an under-studied population. As a result, the social problems of poor urban whites are not well understood. We posit that these whites live in neighborhoods where they are in the ethnic minority. As such, it is possible that they experience the same discriminatory treatment from agents of societal authority such as, school teachers, police officers, social service staff, and others in positions of power to which African Americans living in such communities are exposed. If these social agents are, themselves, predominantly white, this may be a form of class-based intra-ethnic discrimination, whereby whites in authority hold prejudice toward low-income whites. Alternatively, there may a greater proportion of African Americans or other minorities in positions of authority in these communities. Therefore, these low-income urban-dwelling whites may frequently encounter non-white police officers, school teachers, and social service workers. Under this scenario, the perceived discrimination may be ethnic or class-based or both.

The operationalization of discrimination to include how much a person is bothered by the discrimination is an important methodological deviation from previous studies examining discrimination and health (5, 6, 8, 13, 21). Some studies have measured coping response (19, 21); however, in keeping with the Clark (10) model, a person's coping response is not relevant unless the person has perceived discrimination as a stressor. We posit that being bothered is a proxy for perceiving the discrimination stimuli as stressful. Future research should examine the potentially mediating effect of coping response and the possible moderating affects of individual characteristics such as family history, socioeconomic status, age, gender, psychological factors, and behavioral factors that may influence the magnitude of the relationship between the stimuli and a person's perception of discrimination (10).

The prevalence of depression found in this population is more than twice the rate found in the general U.S. population. Major depression has been estimated to occur in the general U.S. population at a 12-month prevalence of 6.7 percent (24) compared to 12.2 percent in this study population meeting the criteria for major depression. General anxiety disorders have been estimated in the U.S. population with a 12-month prevalence of 3 percent (24). It has been established that whites, compared to non-whites (25), and low-income individuals (25-28) experience higher rates of mental health. We suspect that these findings are a result of a variety of factors but discrimination in inner-city whites is a factor that has not been previously considered as a contributor to rates of mental illness in the white population.

Our study sheds light on one possible contributor to the high rates of depression in low-income, white urban-dwellers. It may be that whites have not typically experienced racial discrimination and, as a result, find it more bothersome or stressful. Other authors have also suggested that whites may have less well developed coping mechanisms compared with African Americans for responding to the stress of discrimination (13, 15-17).

Because of the cross-sectional study design, we are unable to make causal inferences. We assert that experiences of discrimination that are bothersome to an individual results in increased levels of depression and anxiety. However, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that the direction of the association between discrimination and mental health that we have assumed may be reversed. Possibly, individuals who are depressed and/or anxious are more likely to perceive and be bothered by racial discrimination. Also, this study was conducted with a sample of low-income, urban-dwelling whites. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to all low-income white populations. Finally, while we suggest that low-income white individuals facing discrimination may actually be facing discrimination based on class, this hypothesis cannot be tested with the perceived racial discrimination measure used in this study.

In summary, this investigation explored the experience of racial discrimination in a population that has been largely ignored. We established that low-income whites living in an inner-city community frequently perceive racial discrimination. We also established that those individuals who are bothered by experiences of discrimination are more likely to be depressed and anxious. Further studies are needed to explore the causes of unusually high rates of depression and anxiety in this population. In addition, qualitative studies would provide a rich description and enhanced understanding of the experience of racial discrimination in poor urban whites.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health [P60MD000214-01] and Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/Ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gee GC, et al. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(10):1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimiation, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):624–631. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler R, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimiation in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam BT. Impact of perceived racial discrimination and collective self-esteem on psychological distress among Vietnamese-American college students: Sense of coherence as mediator. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(3):370–376. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noh S, Kaspar V, Wickrama KAS. Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: Preliminary findings for Korean immigrants. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(7):1269–1274. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.085316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Snyder VNS. Factors associated with acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among married Mexican immigrant women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1987;11(4):475–488. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz A, et al. Discriminiation, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(7):1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siefert K, et al. Social and environmental predictors of maternal depression in current and recent welfare recipients. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(4):510–522. doi: 10.1037/h0087688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark R, et al. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biospychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brondolo E, et al. Perceived racism and blood pressure: A review of the literature and conceptual and methodological critique. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25(1):55–65. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DR, et al. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaVeist TA, Rolley NC, Diala C. Prevalence and patterns of discrimination among US health care consumers. International Journal of Health Services. 2003;33(2):331–334. doi: 10.2190/TCAC-P90F-ATM5-B5U0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, Collins C. US Socioeconomic and Racial Differences in Health: Patterns and Explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21(1):349–386. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harburg E, et al. Socioecological stressor areas and black-white blood pressure: Detroit. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1973;26:595–611. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(73)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC. Stress, social status, and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1979;20(3):259–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaVeist T, et al. Exploring health disparities in integrated communities: An overview of the EHDIC study. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85(1):11–21. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial and gender discrimination: Risk factors for high blood pressure? Social Science & Medicine. 1990;86(10):1370–1378. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90307-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters RM. The relationship of racism, chronic stress emotions, and blood pressure. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(3):234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg DP, Hiller VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionaire. Psychological Medicine. 1979;9:139–145. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dohrenwend BP, et al. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: The causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;255(5047):946–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenblatt M, Sharaf MR. Poverty and mental health: Implications for training. Psychiatric Research Reports. 1967;21:151–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC. Social class and mental illness: A community study. American Journal of Public Health. 1958;97(10):1756–1757. doi: 10.2105/ajph.97.10.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]