Abstract

Social workers have successfully collaborated with African American faith-based organizations to improve health outcomes for numerous medical conditions. However, the literature on Faith-Based Health Promotion for major depression is sparse. Thus, the authors describe a program used to implement a Mental Health Ministry Committee in African American churches. Program goals are to educate clergy, reduce stigma, and promote treatment seeking for depression. Key lessons learned are to initially form partnerships with church staff if there is not a pre-existing relationship with the lead pastor, to utilize a community-based participatory approach, and to have flexibility in program implementation.

Keywords: African Americans, Depression, Faith-Based Health Promotion, Disparities, Community-Based Participatory Research, Implementation

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the leading causes of disability for adults worldwide (Greden, Riba, & McInnis, 2011; Murray & Lopez, 1997). MDD is associated with poor physical health and functioning (Ruo et al., 2008; Weissman et al., 2010), increased medical service utilization, (Johnson, Weissman, & Klerman, 1992; Weissman et al., 2010), and increased risk of suicide (Garlow, Purselle, & Heninger, 2007; Hunt et al., 2003; Joe, Baser, Breeden, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2006; Mann et al., 2005). Kessler and colleagues found that depression had the largest adverse individual-level effect on work performance of any medical or psychiatric condition examined (Kessler et al., 2008). In sum, the individual and societal costs of MDD are devastating.

The relationship between race and MDD is complex (Williams et al., 2007). African Americans are disproportionately affected by low socio-economic status, which increases their risk for developing depression (Jackson, Knight, & Rafferty, 2010; Schnittker & McLeod, 2005; Williams & Jackson, 2005; Williams & Mohammed, 2009) However, large epidemiologic surveys find that African Americans have lower lifetime rates of MDD compared to non-Hispanic white Americans. The lifetime prevalence rate of major depression ranges from to 8.9 to 10.4% among African Americans (Breslau, Kendler, Su, Gaxiola-Aguilar, & Kessler, 2005) compared to 14.6 % to 17.9%% among white Americans (Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Williams et al., 2007). Nevertheless, African Americans with MDD are more impaired and more persistently ill compared to white Americans with MDD (Ezpeleta, Keeler, Erkanli, Costello, & Angold, 2001; Löwe, Schenkel, Carney-Doebbeling, & Göbel, 2006; Williams et al., 2007).

The mental health treatment needs of African Americans with depression are largely unmet. Treatment rates among African Americans with MDD are 33% to 50% lower than treatment rates among white Americans with MDD (Alegria et al., 2008; Gonzalez et al., 2010; Hankerson et al., 2011). African Americans who do receive treatment, as compared to white Americans, are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care, more likely to receive low-quality care (Gonzalez et al., 2010; Young, Klap, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2001), and more likely to terminate treatment prematurely (Ayalon & Alvidrez, 2007). Factors that contribute to these disparities include lack of access (Hines-Martin, Malone, Kim, & Brown-Piper, 2003), financial limitations (Owens et al., 2002), distrust of providers (Nicolaidis et al., 2010), stigma of mental illness (Ayalon & Alvidrez, 2007; Menke & Flynn, 2009; Mojtabai et al., 2011), and culturally encapsulated attributions of disease etiology (Breland-Noble, Bell, Burriss, & Board, 2011).

Community-based interventions hold promise for raising awareness and promoting depression treatment seeking among African Americans (Austin & Claiborne, 2011; Wells, Miranda, Bruce, Alegria, & Wallerstein, 2004; Wells et al., 2002). Community-based interventions involve either collaborations with community-based agencies or attempts to change individual behaviors by reaching people in their normal community settings. They can also aim to target community values and attitudes (i.e., stigma) (Bruce, Smith, Miranda, Hoagwood, & Wells, 2002). These interventions typically employ principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR), a methodology in which mental health professionals, researchers, and community members are equal partners throughout intervention planning, development, and implementation (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). CBPR appears to be an especially promising approach for African Americans, many of whom distrust healthcare professionals due to the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study and enduring years of racial discrimination (Hamilton et al., 2006; McCallum, Arekere, Green, Katz, & Rivers, 2006; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006; Williams & Mohammed, 2009).

Social workers have successfully partnered with community-based organizations to deliver a wide range of mental health services. Social workers provide the majority of mental health care, psychological services, and health crisis interventions in the United States (Block, 2006). Social workers also provide culturally sensitive educational programs to increase the health awareness among racial/ethnic minorities (Austin & Claiborne, 2011). As such, social workers are ideally suited to participate in community-based mental health promotion for African Americans.

Role of the Black Church

The “Black Church” is a term that encompasses the seven predominantly African American denominations of the Christian faith (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). Black churches are trusted, easily accessible, and prominent institutions in many African American communities. The Black Church has a storied history of providing health, social, and educational services for community members (Thomas, Quinn, Billingsley, & Caldwell, 1994). The major Black Church denominations have an estimated membership of 24 million people (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990), and African Americans have the highest documented rates of church attendance among all racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. (Chatters, Taylor, Bullard, & Jackson, 2009; Wells, Cagle, & Bradley, 2006). Thus, the Black Church can reach extremely broad populations and may be uniquely suited to facilitate mental health promotion in the African American community (Bopp & Webb, 2012).

Clergy have an invaluable role in mental health service delivery in the U.S. Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey indicate that a higher percentage of people sought help for mental disorders from clergy (25%) compared to psychiatrists (16.7%) or general medical doctors (16.7%) (Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, 2003). African American clergy are the primary source of mental health care for a large, socioeconomically diverse cohort of African Americans (Levin, 1986; Molock, Matlin, Barksdale, Puri, & Lyles, 2008; Young, Griffith, & Williams, 2003). African American clergy are also trusted “gatekeepers” for referrals to mental health professionals (Neighbors, Musick, & Williams, 1998; Young et al., 2003). However, clergy may not have sufficient training to manage depression, substance use disorders, domestic violence, and psychotic disorders (Hankerson, Watson, Lukachko, Fullilove, & Weissman, 2013; Moran et al., 2005). It is important for clergy to be educated about the signs and symptoms of depression and to be knowledgeable about the mental health resources available in their community.

Faith-Based Health Promotion

Given the centrality of the Black Church in African American culture, Faith-Based Health Promotion (FBHP) has received growing attention from researchers and clinicians as a way to implement culturally sensitive, community-based health programs (Campbell et al., 2007). FBHP is designed to provide measurable benefits to community members through education, screening, and treatment (DeHaven, Hunter, Wilder, Walton, & Berry, 2004; Ransdell, 1995). FBHP has proven effective at improving health outcomes for numerous medical conditions including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and HIV/AIDS (Boltri et al., 2006; Boltri et al., 2008; Bowie, Wells, Juon, Sydnor, & Rodriguez, 2008; Campbell et al., 2004; Campbell et al., 2000; DeHaven et al., 2004; Flack & Wiist, 1991; Hatcher, Burley, & Lee-Ouga, 2008; Tyrell et al., 2008). However, the current body of literature on FBHP for depression is limited. A recent systematic review of FBHP for mental disorders among African Americans found only eight empirical studies (Hankerson & Weissman, 2012). The majority of these studies focused on substance use disorders among adult participants. Depression was the primary outcome in only one of these studies (Mynatt, Wicks, & Bolden, 2008). Since African Americans are three times more likely than white Americans to cite intrinsic spirituality (i.e., prayer) as an extremely important component of depression care (Cooper, Brown, Vu, Ford, & Powe, 2001), FBHP offers an opportunity to incorporate cultural preferences into health promotion activities.

The long-term sustainability of FBHP initiatives must be considered if these programs are to have tangible effects on communities. Organizational factors (e.g., staff cohesion, and communication) and resources (e.g., staffing levels and training) are important characteristics to consider when planning to implement FBHP initiatives (Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002). A “Health Ministry” is a committee of church leaders and community members operating within a church that provides health education and services to congregants. Austin and Harris (2011) successfully implemented Health Ministry Committees among a coalition of Black Churches in upstate New York that were focused on addressing racial disparities in diabetes mellitus. A Mental Health Ministry Committee could provide the organizational infrastructure needed to implement and sustain FBHP for depression (Austin & Claiborne, 2011). Thus, the purpose of this paper is to describe a program designed to implement a Mental Health Ministry Committee in African American churches.

Program Description

The lead author is a Certified Social Worker with the Mental Health Association in New Jersey. In 2004, she created the Promoting Emotional Wellness and Spirituality (PEWS) Program with funding from a pilot grant from the State of New Jersey’s Department of Mental Health Services. The program acronym, “PEWS”, is the name of bench-like seats in churches that are used to seat parishioners during Sunday services. Using language with which church staff and community members are familiar emphasized the culturally sensitive nature of the program. The primary goals of the PEWS Program are: 1) to educate clergy about the signs and symptoms depression; 2) to reduce stigma associated with depression; and 3) to promote mental health treatment seeking for depression among communities of color. A secondary goal is to educate clinicians about the importance of assessing a client’s spiritual beliefs in the course of treatment.

Community Engagement

The lead author formed a PEWS Community Advisory Committee to engage community members and oversee implementation of the PEWS program. The Advisory Committee was composed of three ministers, one mental health consumer, one lay community member, and four mental health providers. The PEWS Advisory Committee garnered community support for the program by sponsoring a “Spirituality and Wellness Conference” in 2007 and 2008 at the Paul Robeson Center on Rutgers University’s Newark Campus. This trusted venue was selected to emphasize the PEWS Program’s desire to be culturally sensitive toward its audience. The conferences brought together mental health professionals and faith-based leaders to highlight their respective roles in providing mental health care to African Americans. Faith leaders from Baptist, Catholic, African Methodist Episcopal, Unitarian, and non-denominational churches attended the conferences. Mental health professionals from state and local government, community non-profit organizations, academic institutions, and hospitals also attended. The majority of the conference attendees were mental health consumers, consumer providers (i.e., self-help center staff) and lay community members (interested family members of mental health consumers and church congregants). These conferences allowed clergy to develop relationships with mental health professionals and create a reliable referral network. Conferences featured a keynote speaker, videos, and breakout workshop sessions. Table 1 shows the program agenda for the 2007 conference. A similar agenda was employed in the 2008 conference.

TABLE 1. Program Overview of the 2007 Spirituality and Wellness Conference.

| Agenda Item | Presentation Topic | Presenter Credentials |

|---|---|---|

| Keynote Speaker | “The Importance of Mental and Spiritual Health” | Senior Pastor of a Baptist Church |

| Video | “Getting to the Other Side – African Americans and Co- Occurring Disorders” |

N/A |

| Workshops | “How Do I Know There’s a Problem?” Identifying Symptoms & Signs of Mental Illness and Substance Abuse” |

Clinical Psychologist |

| “How to Develop a Plan to Stay Well: Basic WRAP (Wellness & Recovery Plan) Principles” |

Clinical Social Worker | |

| “How to Discuss your Client’s Spiritual Beliefs &Incorporate Them into Their Recovery Process” |

Master of Divinity | |

| “What Caregivers Need to Do to Take Care of Themselves” | Licensed Clinical Social Worker | |

| “African American Culture and the Stigma of Mental Illness” | Administrator from New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services |

In total, over 400 participants attended the two PEWS Conferences. At the conclusion of each conference, a majority of clinicians reported being more sensitive to the potential spiritual needs of their clients; identified spirituality as one of the essential dimensions of wellness; and reported a willingness to incorporate spirituality into treatment and/or discharge plans of their clients. The conferences garnered support for addressing depression in the African American community and led to the development of a training curriculum for clergy and community members.

Components of the PEWS Program Training Curriculum

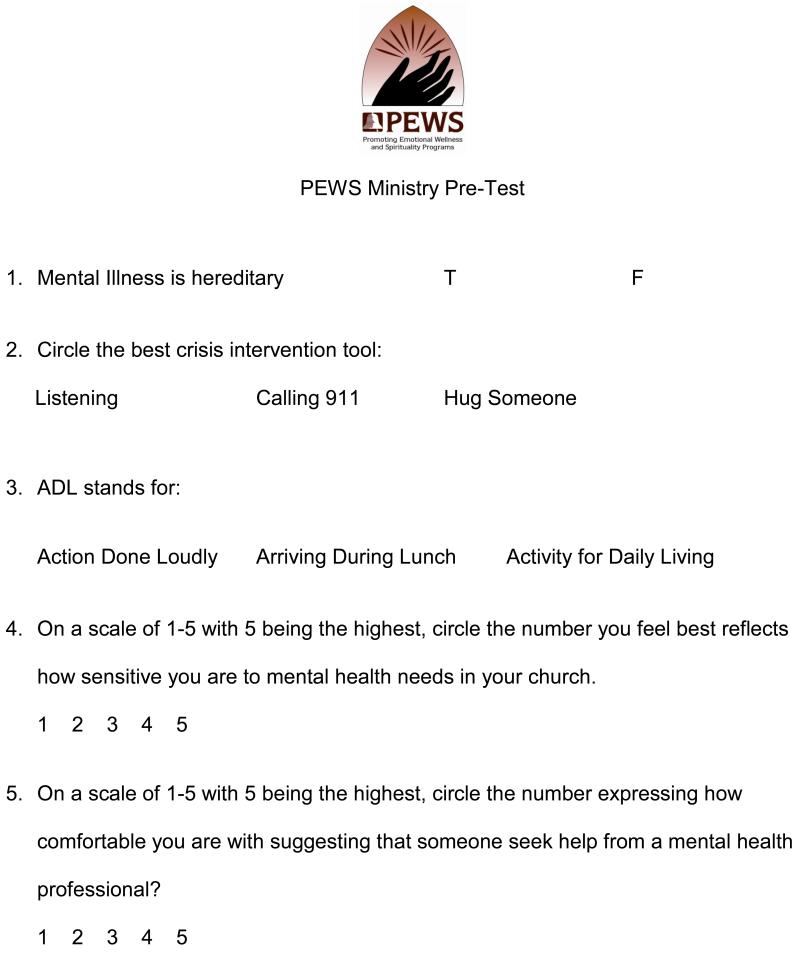

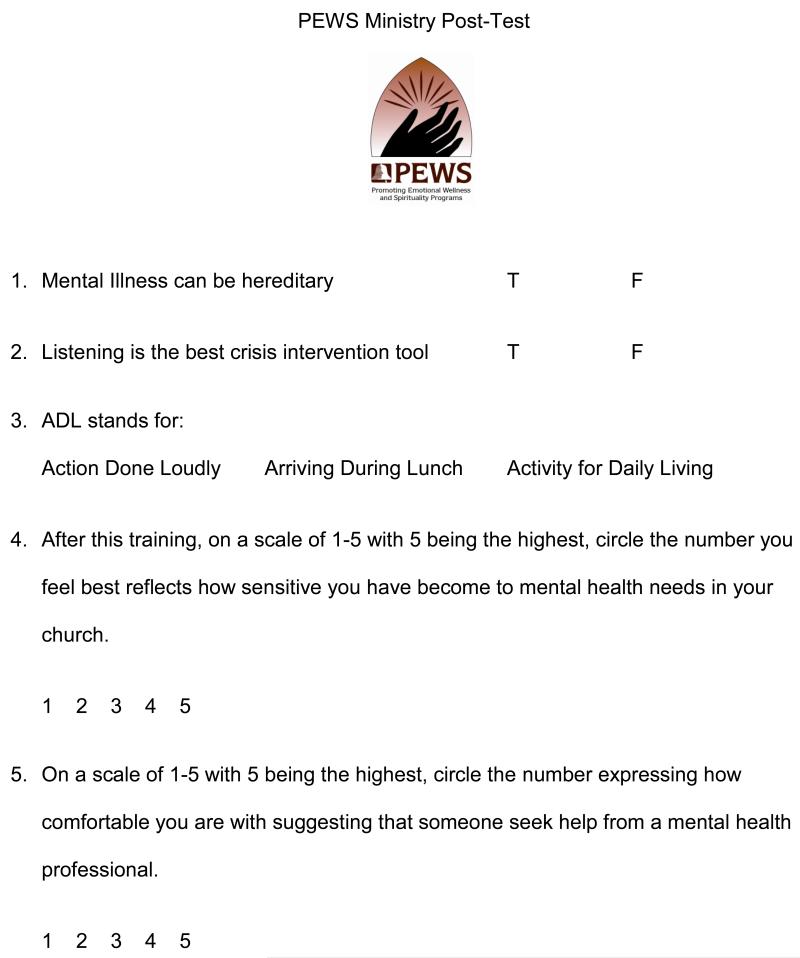

The PEWS Program offers a four-day, 10-hour training curriculum for churches that can either expand their current Health Ministry to include a mental health component or develop a free-standing Mental Health Ministry Committee. The 10-hour training is facilitated jointly by a clinical social worker, pastor, and certified substance abuse counselor. The training program consists of 1) a pre-test to assess the congregation’s baseline knowledge; 2) video vignettes of people who successfully received mental health treatment; 3) an overview of signs, symptoms, and treatment options for depression and other common mental disorders; 4) an introduction to effective communication techniques; 5) basic crisis intervention skills; 6) technical assistance to link congregants to higher levels of care; and 7) a post-test to assess participants’ retention of the training material. Table 2 shows the agenda for the training curriculum. To facilitate standardized implementation of this training, the PEWS Advisory Committee created a manual, “Creating a Vibrant Partnership between Communities of Faith and Mental Health Providers – How to Develop a Successful PEWS Mental Health Ministry” (Figure 1).

TABLE 2. Ten-Hour Training Curriculum for the Promoting Emotional Wellness and Spirituality Program.

| Training Day | Curriculum Content |

|---|---|

| Day 1 (2 hours) | I. Welcome and Introduction |

| II. Pre-Test | |

| III. Overview of Mental Health Issues | |

| A. Prevalent Psychiatric Disorders | |

| 1. Signs and Symptoms | |

| 2. Treatment / Medication | |

| B. Introduction to Effective Communication and Helping Techniques |

|

| Day 2 (3 hours) | IV. Effective Communication and Helping Techniques (Continued) |

| Day 3 (2 hours) | V. Crisis Intervention Skills |

| Day 4 (3 hours) | VI. Referral and Linkage to Community Services |

| VII. Post-Test | |

| VIII. Question and Answer Period |

FIGURE 1. Program Manual for How to Develop a Promoting Emotional Wellness and Spirituality Mental Health Ministry Committee.

Two videos central to the PEWS Program training curriculum were created with funding by the Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Both of these videos were created through equitable partnerships with three local ministers, all of whom appear in the videos, and several community members. The first video, “Anything But Crazy,” chronicles the experiences of several individuals who sought church support during a depressive episode. It also shows a pastor talking about the importance of religious leaders being knowledgeable about mental disorders and community resources available for their congregants. The title of the video refers to a comment made by one of the mental health consumers featured in the video who states, “In the African American community, people will admit they are a drug user, are HIV positive….they’ll admit they’re anything but crazy.”

The second video, “Getting to the Other Side: African Americans and Co-Occurring Disorders,” discusses the relationship between spirituality and healing for people with co-morbid mental illness and substance use. In the video a pastor speaks about the relationship between broken family systems, community violence, and co-occurring mental disorders. Consumers featured in the video share their personal stories and tell how spirituality played a critical role in helping them achieve wellness.

Implementing the PEWS Mental Health Ministry Committee

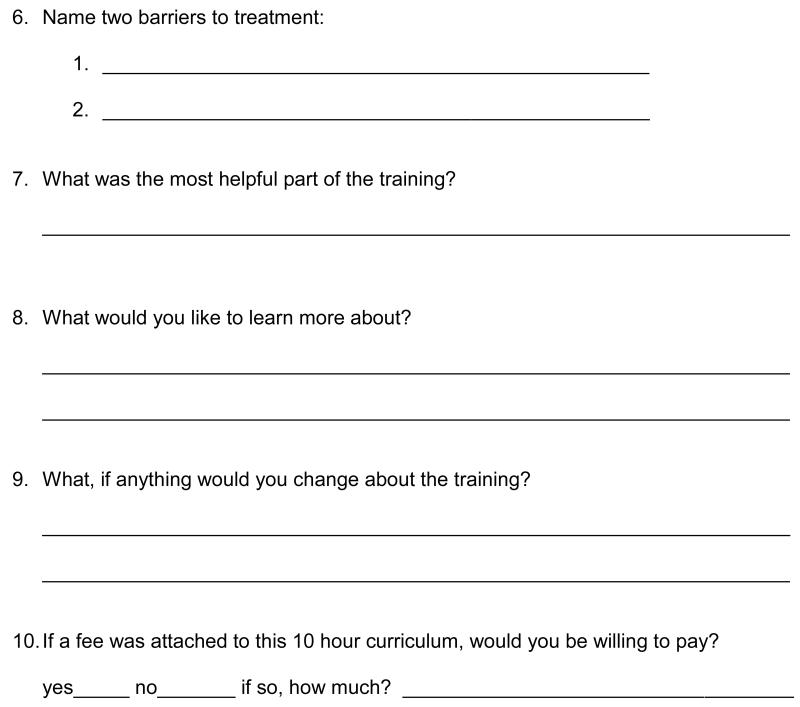

The PEWS Advisory Committee used a CBPR approach to implement a Mental Health Ministry Committee in one medium-sized (n = 400 congregants) Baptist church and one mega-sized (n = 2,000 congregants) Baptist church. Both churches are located in urban cities in New Jersey and serve congregations that are approximately 98% African American. Prior to implementing the PEWS training curriculum at each church, the lead author conducted a two-hour “orientation” session that was open to the general public. This orientation provided a historical overview of the PEWS program, rationale for the curriculum, preview of the training content, and outline of the learning objectives. Following the orientation session, interested community members took the pre-test and those who completed the training program took the post-test (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Since the pre- and post-tests were not originally designed for research studies, the PEWS Advisory Committee did not attain institutional review board approval and did not test the measures for comprehension or face validity prior to giving them to community members. Thus, we are unable to report the results of the pre- and post-tests in this article. Despite these limitations, we describe how the implementation of a Mental Health Ministry Committee differed at each church.

FIGURE 2. Pre-Test for the Promoting Emotional Wellness and Spiritual Programs Mental Health Ministry Training Program.

FIGURE 3. Post-Test for the Promoting Emotional Wellness and Spiritual Programs Mental Health Ministry Training Program.

The lead author is a member and has a prominent leadership role at the medium-sized church in which the PEWS Program was implemented. She leveraged her church affiliation to directly approach the lead pastor about implementing the PEWS Program. The pastor enthusiastically agreed to implement the program and later became Chair of the PEWS Advisory Committee. Facilitators delivered the 10-hour training curriculum on two weeknights and two Saturday mornings over the course of two weeks.

A total of 26 people attended the PEWS trainings at the medium-sized church. After completing the training program, church members decided to implement a “Health and Wellness Ministry” Committee. They decided to use the term “Wellness,” instead of “Mental Health,” due to concerns about stigma. The Health and Wellness Ministry Committee was composed of nine members, whose vocations ranged from a pharmacist, registered nurse, church deacons, mental health consumers, and clinical social workers. Members of the Committee invited mental health professionals to speak at their annual Health Fair. The Health and Wellness Ministry Committee helped to refer depressed congregants to local mental health providers. The Committee also started a Bereavement Support Group to help struggling parishioners cope with various losses. The lead minister raised awareness about depression in his sermons by informing parishioners that October is “National Depression Awareness Month.”

At the mega-church, members of the PEWS Advisory Committee did not have a formal relationship with the lead pastor. Advisory Committee members engaged church leaders, such as deacons, church secretaries, and members of the church usher board, by attending the church’s annual health fair and other church-sponsored events. While attending these programs, Advisory Committee members provided church leaders with a brief overview of the PEWS Program. Due to these outreach efforts, church leaders asked the lead pastor to implement the PEWS Program at their church. The pastor then invited a member of the Advisory Committee to describe the PEWS Program during a Sunday worship service. This program description generated enough interest in the PEWS Program that the pastor decided to proceed with implementation.

During implementation of the training curriculum, faith leaders at the mega-church served as intermediaries between the PEWS Advisory Committee and the lead pastor. A total of 70 people attended the PEWS training at the mega-church, where the training program was implemented on four consecutive Tuesday evenings. The church decided to add a Mental Health Committee to their pre-existing “Nurses Auxiliary.” Prior to implementing the PEWS Program, the Nurses Auxiliary only offered programs about physical health problems. After implementation, the Mental Health Committee sponsored several church-based events featuring mental health professionals. These programs educated the congregation about depression, the relationship between physical and mental health, parenting skills, and stress management.

Implementation Lessons Learned

-

Form partnerships with church leaders and staff if there is not a pre-existing relationship with the lead pastor

Clergy have numerous competing responsibilities and rely heavily on church staff for suggestions about church programming (Young et al., 2003). At the mega-church, members of the PEWS Advisory Committee did not have a pre-existing relationship with the lead pastor. Advisory Committee members initially formed relationships with church leaders, who subsequently persuaded the lead pastor to implement the program. This engagement strategy caused church leaders to feel ownership of the PEWS Program, and they served as local “champions” during the implementation process. FBHP initiatives are more likely to be accepted by community members when there are implementation champions in the organization (Campbell et al., 2007; Scheirer, 2005).

-

Employ a CBPR approach to increase community engagement

PEWS Program facilitators and community members collaborated as equitable partners during the implementation process (Israel et al., 2005; Minkler, 2010; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). The 2007 and 2008 “Spirituality and Wellness Conferences” were essential to engaging the community. The conferences allowed mental health professionals, church leaders, and members of the PEWS Advisory Committee to build trusting relationships. These relationships laid the foundation for church leaders to have an active role in program implementation.

-

Be flexible when implementing the 10-hour training curriculum

The PEWS training curriculum was implemented based on the availability and preferences of each church. The training was completed in two weeks at the medium-sized church and four weeks at the mega-church. Accommodating community members’ busy schedules and the availability of church resources was an essential aspect to consider for implementation. If the Advisory Committee required a rigid timeframe by which to implement the training curriculum, church leaders may not have decided to implement the program.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Social workers have successfully employed FBHP to deliver educational and health services for numerous chronic medical conditions (Austin & Harris, 2011; DeHaven et al., 2004). The PEWS Program is innovative because it provides information on how to implement faith-based mental health promotion programs, which are lacking in the literature (Hankerson et al., 2013). We discuss the clinical and research implications of implementing the PEWS Program in faith-based settings.

A crucial element of the PEWS Program is to educate and engage clergy throughout the implementation process. More people in the U.S. seek help for depression from clergy than from psychiatrists or general medical providers (Wang et al., 2003). African American clergy may be more likely than white clergy to describe depression as a temporary time of weakness, instead of a biological mood disorder (Payne, 2009; Proeschold-Bell et al., 2012). Such beliefs could deter African American clergy from referring community members to mental health professionals, inadvertently prolonging suffering when professional treatment is warranted. Educating African American clergy can dispel these beliefs and link people to clinical services. Collaborating with clergy throughout implementation of the PEWS Program is also an opportunity to harness their support, which increases the likelihood that the program will be sustained long-term (Campbell et al., 2007).

The PEWS program employs video vignettes to combat the stigma associated with depression and co-morbid disorders. Stigma has been cited as a barrier to depression treatment among African Americans (Alvidrez, Snowden, & Kaiser, 2010; Alvidrez, Snowden, Rao, & Boccellari, 2009; Franz et al., 2010). Stigma may be especially strong in some faith-based settings, as community members may attribute depression to a lack of faith in God or under one’s own control to overcome (Bell et al., 2011). Evidence suggests that anti-stigma educational programs must be targeted and contextualized for the local community. By showing testimonials from credible community members who are similar in ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and religion as members of the church target audience, the PEWS Program is employing principles from strategic stigma change (Corrigan, 2011). Future research is needed to assess the impact the PEWS video vignettes have on changing negative attitudes and help-seeking for depression.

Another area deserving investigation is the feasibility of adapting the PEWS program for use among other religious groups. To date, the PEWS Program has been adapted for use among leaders in the Muslim community. Results from this adaptation are forthcoming. A leader in the Jewish community presented the core elements of the PEWS Program to rabbis of his synagogue and encouraged them to hire a clinician to provide services to members of his synagogue. Presenting the PEWS Program to members of different religious groups and racial/ethnic groups may reveal strategies by which to disseminate Mental Health Ministry Committees on a large scale.

Evaluating the long-term impact of the PEWS Program has been hampered by inconsistent funding. Two separate private foundations provided limited funding towards salary support for the lead author and supplies for the 2008 Spirituality and Wellness Conference. After the initial pilot grant funding expired, the New Jersey Department of Mental Health Services did not allocate additional funds to sustain the PEWS Program. Lack of financial stability has limited the PEWS Program’s ability to provide follow-up training sessions to church leaders once the Mental Health Ministry Committees have been implemented. To address this challenge, churches could form strategic partnerships with academic institutions to bolster their chances of securing grant and other sources of funding (Jones & Wells, 2007; Lindamer et al., 2008; Wells et al., 2004). We also surmise that churches will need to devote finances and other resources to sustaining Mental Health Ministry Committees. Given the numerous ways that Black Churches serve their communities, we realize that providing additional funds for FBHP may be difficult. However, devoting such resources will help churches to assess what tangible impacts FBHP have on under-served communities.

LIMITATIONS

The main limitation of this article is the lack of quantitative data from either the pre- and post-test assessments or the conference evaluations. The PEWS Program was not initially designed for research purposes, but rather emerged as a grass roots effort to promote treatment seeking for depression among African Americans. As such, community members who took the PEWS Program 10-hour training curriculum were not able to sign informed consent for participation in a research study. The next steps in the development of the PEWS Program are to evaluate the pre- and post-test for face validity and secure approval from an institutional review board to conduct a formal pilot study. Thereafter, we will employ more rigorous research designs, such as randomized-controlled trials, to measure the effects of the PEWS Program training on participant knowledge of mental disorders, treatment seeking for depression, and referrals from clergy to mental health professionals.

Our discussion also has limited generalizability to other faith-based settings. The PEWS Program has been implemented in two Baptist churches with predominantly African American congregations in the state of New Jersey. Future studies should explore how to implement the PEWS program in churches with varying denominations (i.e., Methodist, Episcopal, and Catholic), congregation sizes, and racial/ethnic groups. It will also be important to evaluate how implementation varies in different geographic regions of the country.

CONCLUSION

The PEWS Program provides the organizational infrastructure necessary to implement a Mental Health Ministry Committee in faith-based settings. Key elements of program implementation are to engage church leaders, such as deacons and church secretaries, if a direct relationship with the lead pastor does not exist; utilize a community-based participatory approach; and have flexibility with program implementation. Churches may want to partner with academic institutions, which can offer institutional support via grants and research volunteers. These community-academic partnerships can be used to conduct empirical research designed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of programs sponsored by Mental Health Ministry Committees.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by grant 5-T32 MH015144 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); grant #17694 from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD); and funding from the Templeton Foundation. We would also like to acknowledge the Victoria Foundation and the Health Care Foundation who provided funding to support elements of the training program.

Contributor Information

Laverne Williams, Mental Health Association in New Jersey, Verona, NJ.

Robyn Gorman, Mental Health Association in New Jersey, Verona, NJ.

Sidney Hankerson, Columbia University, College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY; New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY.

REFERENCES

- Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, Cao Z, Chen CN, Takeuchi D, Jackson J, Meng XL. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(11):1264–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Kaiser DM. Involving consumers in the development of a psychoeducational booklet about stigma for black mental health clients. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(2):249–258. doi: 10.1177/1524839908318286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Rao SM, Boccellari A. Psychoeducation to address stigma in black adults referred for mental health treatment: a randomized pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 2009;45(2):127–136. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin S, Harris G. Addressing health disparities: the role of an African American health ministry committee. Soc Work Public Health. 2011;26(1):123–135. doi: 10.1080/10911350902987078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SA, Claiborne N. Faith Wellness Collaboration: A Community-Based Approach to Address Type II Diabetes Disparities in an African-American Community. Soc Work Health Care. 2011;50(5):360–375. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2011.567128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, Alvidrez J. The experience of Black consumers in the mental health system--identifying barriers to and facilitators of mental health treatment using the consumers’ perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2007;28(12):1323–1340. doi: 10.1080/01612840701651454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Franks P, Duberstein PR, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Garcia EF, Kravitz RL. Suffering in silence: reasons for not disclosing depression in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(5):439–446. doi: 10.1370/afm.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block P. Alternative, complementary, and integrative medicine in a conventional setting. In: Gehlert S, Browne TA, editors. Handbook of Health Social Work. John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boltri JM, Davis-Smith M, Zayas LE, Shellenberger S, Seale JP, Blalock TW, Mbadinuju A. Developing a church-based diabetes prevention program with African Americans. The Diabetes Educator. 2006;32(6):901–909. doi: 10.1177/0145721706295010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltri JM, Davis-Smith YM, Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Okosun IS, Cornelius ME. Diabetes prevention in a faith-based setting: results of translational research. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(1):29–32. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000303410.66485.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Webb B. Health promotion in megachurches: an untapped resource with megareach? Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(5):679–686. doi: 10.1177/1524839911433466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie JV, Wells AM, Juon H-S, Sydnor KD, Rodriguez EM. How old are African American women when they receive their first mammogram? Results from a church-based study. J Community Health. 2008;33(4):183–191. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble AM, Bell CC, Burriss A, Board APAA. “Mama just won’t accept this”: adult perspectives on engaging depressed African American teens in clinical research and treatment. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18(3):225–234. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychol Med. 2005;35(3):317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Smith W, Miranda J, Hoagwood K, Wells KB. Community-based interventions. Ment Health Serv Res. 2002;4(4):205–214. doi: 10.1023/a:1020912531637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, James A, Hudson MA, Carr C, Jackson E, Oakes V, Demissie S, Farrell D, Tessaro I. Improving multiple behaviors for colorectal cancer prevention among african american church members. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):492–502. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Motsinger BM, Ingram A, Jewell D, Makarushka C, Beatty B, Dodds J, McClelland J, Demissie S, Demark-Wahnefried W. The North Carolina Black Churches United for Better Health Project: intervention and process evaluation. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(2):241–253. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Jackson JS. Race and ethnic differences in religious involvement: African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2009;32(7):1143–1163. doi: 10.1080/01419870802334531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, Ford DE, Powe NR. How important is intrinsic spirituality in depression care? A comparison of white and African-American primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):634–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. Best Practices: Strategic Stigma Change (SSC): Five Principles for Social Marketing Campaigns to Reduce Stigma. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(8):824–826. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.8.pss6208_0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Keeler G, Erkanli A, Costello EJ, Angold A. Epidemiology of psychiatric disability in childhood and adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):901–914. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack JM, Wiist WH. Cardiovascular risk factor prevalence in African-American adult screenees for a church-based cholesterol education program: the Northeast Oklahoma City Cholesterol Education Program. Ethn Dis. 1991;1(1):78–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz L, Carter T, Leiner AS, Bergner E, Thompson NJ, Compton MT. Stigma and treatment delay in first-episode psychosis: a grounded theory study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(1):47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow SJ, Purselle DC, Heninger M. Cocaine and alcohol use preceding suicide in African American and white adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(6):530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greden JF, Riba MB, McInnis MG, editors. Treatment Resistant Depression: A Roadmap for Effective Care. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LA, Aliyu MH, Lyons PD, May R, Swanson CL, Jr., Savage R, Go RCP. African-American community attitudes and perceptions toward schizophrenia and medical research: an exploratory study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(1):18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson SH, Fenton MC, Geier TJ, Keyes KM, Weissman MM, Hasin DS. Racial differences in symptoms, comorbidity, and treatment for major depressive disorder among black and white adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(7):576–584. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson SH, Watson KT, Lukachko A, Fullilove MT, Weissman M. Ministers’ perceptions of church-based programs to provide depression care for african americans. J Urban Health. 2013;90(4):685–698. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9794-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson SH, Weissman MM. Church-Based Health Programs for Mental Disorders Among African Americans: A Review. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(3):243–249. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher SS, Burley JT, Lee-Ouga WI. HIV prevention programs in the black church: A viable health promotion resource for African American women? Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2008;17(3-4):309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hines-Martin V, Malone M, Kim S, Brown-Piper A. Barriers to mental health care access in an African American population. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2003;24(3):237–256. doi: 10.1080/01612840305281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt IM, Robinson J, Bickley H, Meehan J, Parsons R, McCann K, Flynn S, Burns J, Shaw J, Kapur N, Appleby L. Suicides in ethnic minorities within 12 months of contact with mental health services. National clinical survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:155–160. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among blacks in the United States. Jama. 2006;296(17):2112–2123. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267(11):1478–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, White LA, Birnbaum H, Qiu Y, Kidolezi Y, Mallett D, Swindle R. Comparative and interactive effects of depression relative to other health problems on work performance in the workforce of a large employer. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(7):809–816. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318169ccba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(4):197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. Roles for the Black Pastor in Preventive Medicine. Pastoral Psychology. 1986;35(2):94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Duke University Press; Durham and London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lindamer LA, Lebowitz BD, Hough RL, Garcia P, Aquirre A, Halpain MC, Depp C, Jeste DV. Public-academic partnerships: improving care for older persons with schizophrenia through an academic-community partnership. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(3):236–239. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Schenkel I, Carney-Doebbeling C, Göbel C. Responsiveness of the PHQ-9 to Psychopharmacological Depression Treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):62–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. Jama. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum JM, Arekere DM, Green BL, Katz RV, Rivers BM. Awareness and knowledge of the U.S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee: implications for biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(4):716–733. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke R, Flynn H. Relationships between stigma, depression, and treatment in white and African American primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(6):407–411. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a6162e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Linking Science and Policy Through Community-Based Participatory Research to Study and Address Health Disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S81–S87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass Publishing; San Francisco: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, Wells KB, Pincus HA, Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2011;41(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molock SD, Matlin S, Barksdale C, Puri R, Lyles J. Developing suicide prevention programs for African American youth in African American churches. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(3):323–333. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M, Flannelly KJ, Weaver AJ, Overvold JA, Hess W, Wilson JC. A Study of Pastoral Care, Referral, and Consultation Practices Among Clergy in Four Settings in the New York City Area. Pastoral Psychology. 2005;53(3):255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynatt S, Wicks M, Bolden L. Pilot study of INSIGHT therapy in African American women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22(6):364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Musick MA, Williams DR. The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(6):759–777. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Timmons V, Thomas MJ, Waters AS, Wahab S, Mejia A, Mitchell SR. “You don’t go tell White people nothing”: African American women’s perspectives on the influence of violence and race on depression and depression care. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1470–1476. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, Ialongo NS. Barriers to Children’s Mental Health Services. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(6):731–738. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JS. Variations in pastors’ perceptions of the etiology of depression by race and religious affiliation. Community Ment Health J. 2009;45(5) doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proeschold-Bell RJ, LeGrand S, Wallace A, James J, Moore HE, Swift R, Toole D. Tailoring health programming to clergy: findings from a study of United Methodist clergy in North Carolina. J Prev Interv Community. 2012;40(3):246–261. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.680423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransdell LB. Church-based health promotion: An untapped resource for women 65 and older. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1995;9(5):333–336. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruo B, Baker DW, Thompson JA, Murray PK, Huber GM, Sudano JJ., Jr. Patients with worse mental health report more physical limitations after adjustment for physical performance. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):417–421. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816f858d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA. Is Sustainability Possible? A Review and Commentary on Empirical Studies of Program Sustainability. American Journal of Evaluation. 2005;26(3):320–347. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, McLeod JE. The Social Psychology of Health Disparities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Billingsley A, Caldwell C. The characteristics of northern black churches with community health outreach programs. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(4):575–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrell CO, Klein SJ, Gieryic SM, Devore BS, Cooper JG, Tesoriero JM. Early results of a statewide initiative to involve faith communities in HIV prevention. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(5):429–436. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333876.70819.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Neria Y, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Lantigua R, Shea S, Olfson M. Positive screens for psychiatric disorders in primary care: a long-term follow-up of patients who were not in treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JN, Cagle CS, Bradley PJ. Building on Mexican-American cultural values. Nursing. 2006;36(7):20–21. doi: 10.1097/00152193-200607000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Miranda J, Bruce ML, Alegria M, Wallerstein N. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Miranda J, Bauer MS, Bruce ML, Durham M, Escobar J, Ford D, Gonzalez J, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Lawson W, Lewis L, McGuire T, Pincus H, Scheffler R, Smith WA, Unutzer J. Overcoming barriers to reducing the burden of affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(6):655–675. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, Jackson JS. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(2):325–334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JL, Griffith EE, Williams DR. The integral role of pastoral counseling by African-American clergy in community mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(5):688–692. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]