Abstract

To date there is no validated peripheral biomarker to assist with the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Platelet proteins have been studied as AD biomarkers with relative success. In the present study we investigated whether platelet BACE1 levels differ between AD and cognitively normal (CN) control patients. Using a newly developed ELISA method, we found that BACE1 levels were significantly lower in AD compare to CN subjects. These data were supported by the observation that several BACE1 isoforms, identified by Western blotting, were also lower in AD platelets. This proof-of-concept study provides evidence for testing platelet BACE1 levels as a peripheral AD biomarker using a novel, sensitive and inexpensive method.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, BACE1, Biomarker, Peripheral, Platelets

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the slow decline of cognition and functional abilities over time. The diagnosis for probable and possible AD relies principally on clinical criteria and neuropsychological tests defined by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA) [1]. The confirmation of the disease is made post-mortem by identifying extracellular senile plaques and intraneuronal fibrillary tangles in the brains of subjects with clinically defined dementia. However, the field critically lacks validated AD-specific peripheral biomarkers to support the diagnosis in living patients or for early detection of patients at risk before symptoms appear. For example, a recent meta-analysis of plasma amyloid beta (Aβ)-40 and 42 showed no consistent results between research centers [2], suggesting that additional markers need to be tested.

Brain senile plaques are mainly constituted of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides that derive from the successive proteolysis of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) by beta- and gamma-secretases [3]. The major β-secretase in AD is the beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) [4]. The process is suspected to occur in neurons in the brain [5], although amyloidogenesis has also been identified in circulating platelets [6]. Intriguingly, it has been estimated that the majority of blood APP and Aβ originates from platelets [7, 8]. Data from several laboratories showed that APP and BACE1 isoform ratios are altered in AD compared to cognitively normal (CN) subjects [9-11]. These observations suggest that APP and BACE1 levels may be altered in AD subject platelets, which might be useful for the development of peripheral biomarkers.

Recently we have proposed the measurement of peripheral BACE1 as AD biomarker [12]. Furthermore, we have developed a new immunoassay that, compared to most other BACE1 assays, detects total BACE1 levels (i.e. most transmembrane and non-transmembrane isoforms) and shows good linearity with human platelet lysates [13]. In the present proof-of-concept study, we hypothesized that total platelet BACE1 levels may differ between AD and CN subjects in a cross-sectional paradigm. To investigate this hypothesis, we employed our new BACE1 ELISA method in conjunction with Western blotting. Both techniques identified a significant decrease in platelet BACE1 levels in AD versus CN subjects.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Isolation of Platelets and Plasma

Study subjects were from the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Cleo Roberts Clinical Research Center. AD was diagnosed by NINDS-ADRDA criteria [1]. CN subjects were defined as cognitively normal (MMSE>28) and suffering no neurodegenerative disease. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all subjects signed Institutional Review Board-approved informed consents. Demographics of the population are presented in Table I. Antecubital venous blood (16-20 mL) was collected in EDTA tubes by an experienced phlebotomist over a nine-month period. Samples were processed within 30 min after collection to isolate platelets and plasma as described earlier [13].

Table I.

Demographics and laboratory features of the population studied.

| CN (n=12) | AD (n=15) | t-value | p-value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 4/8 | 10/5 | |||

| Age (years) | 79.58 [5.04] | 82.08 [5.14] | 1.63 | 0.12 | 0.63 |

| Education (years) | 16.08 [2.35] | 14.13 [2.48] | -2.08 | 0.05 | 0.81 |

| MMSE | 29.33 [0.78] | 19.07 [6.35] | -5.54 | <0.001 | 5.58 |

| Platelet BACE1 (pg/μg protein) | 73.97 [12.95] | 65.10 [7.07] | -2.26 | 0.03 | 0.85 |

| Plasma BACE1 (ng/mL) | 790.5 [142.1] | 712.5 [128.7] | -1.58 | 0.13 | 0.61 |

BACE1 values from ELISA experiments; data shown as Mean [sd]; for t-values, df = 25; effect size – Cohen’s d

ELISA and Western Blot

BACE1 ELISA and Western blot have been reported previously [13]. Briefly, for BACE1 ELISA, 25-100 μg of total protein were loaded in duplicate wells. All samples were analyzed in parallel in a blind manner. For Western blotting, 20-40 μg of total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk and incubated overnight with either mouse anti-BACE1 C-terminal antibody (diluted 1:2,000; #MAB5308; Millipore, Billerica, MA), or rabbit anti-BACE1 N-terminal antibody (1:4,000; #B0681; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). Corresponding secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), and signal detection was carried out with ECL (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and autoradiographic films (Research Products International, Mt. Prospect, IL). After stripping the membranes were reprobed with the complementary N- or C-terminal BACE1 antibody (reversed compared to the first probing), and probed a third time with mouse anti-β-actin (1:8,000; #A1978; Sigma-Aldrich). Films were scanned and densitometry analysis was performed. All experiments were performed at least in duplicate for each subject. Images were processed and figures assembled in Acrobat Photoshop.

Statistical analysis

Two-sample t-tests were used to compare the AD and CN groups. Cohen’s d was used to assess the effect size for the group comparisons. Group differences for BACE1 platelet and plasma levels were then analyzed using ANCOVA, which adjusted for the effects of age and education. Correlation analysis was also carried out to determine the degree of association between platelet and plasma BACE1 levels and MMSE scores. Results with p-values ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

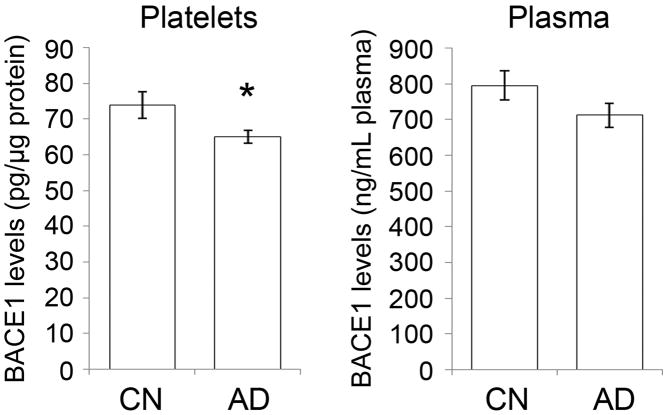

Our population was comprised of 12 CN and 15 AD living subjects. The CN and AD groups did not differ with respect to age, but the CN group had significantly more years of education (Table I). The clinical diagnosis of AD was supported by the lower Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) average score in AD subjects (Table I). Total BACE1 levels were measured in platelet lysates and plasma using a newly developed immunoassay [13]. Data showed a 12% and 10% decrease in total platelet and plasma BACE1 levels, respectively, in AD versus CN subjects (Figure 1). Two sample t-tests yielded statistically significant differences for platelet but not for plasma BACE1 levels. ANCOVA analysis indicated that the group difference was statistically significant for platelet BACE1 levels [F = 5.13 (df = 1, 23), p = 0.03] and yielded a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.85). However, the group difference for plasma BACE1 was not statistically significant [F = 0.71 (df = 1, 23), p = 0.41] and the effect was medium in size (Cohen’s d = 0.63), which was likely due to high inter-individual variations and a less accurate recognition of BACE1 because of matrix effects [13]. Correlational statistics showed that platelet BACE1 levels correlated moderately with the MMSE scores (r = 0.40), but plasma BACE1 levels correlated weakly with MMSE scores (r = 0.25). Nonetheless, the ELISA data showed that BACE1 levels were lower in AD compared to CN platelets.

Figure 1.

ELISA platelet BACE1 levels are lower in AD subjects.

BACE1 ELISA was conducted on platelet lysates and plasma samples from CN (n=12) and AD (n=15) subjects. BACE1 levels were significantly lower in AD compared to CN platelets. No significant difference was obtained for plasma, possibly due to matrix effects which may interfere with the accurate detection of the protein in this tissue as suggested by the high BACE1 concentrations recorded here and previously (see text). * p<0.05.

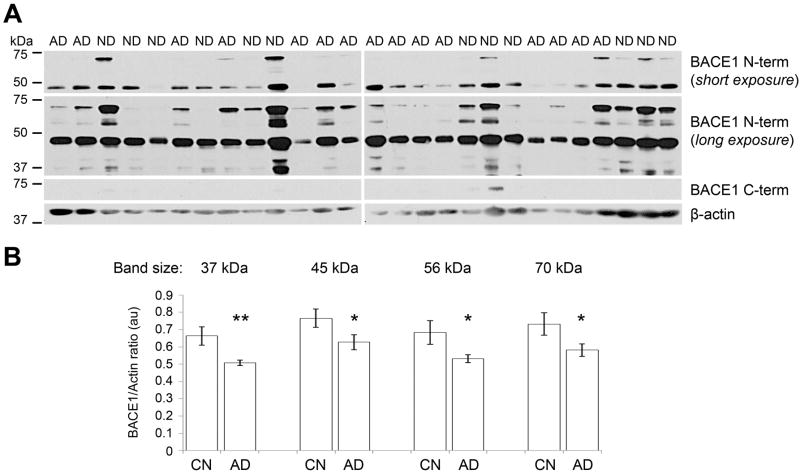

The BACE1 protein displays multiple isoforms migrating at different sizes on Western blots in different tissues [10, 14, 15]. Thus, we investigated whether the decrease in AD platelet BACE1 levels detected by ELISA was due to the decrease in one or several isoforms. For this, we carried out Western blots on platelet lysates from all 27 samples using BACE1 N-terminal and C-terminal specific antibodies. The BACE1 N-terminal antibody, which binds the BACE1 ectodomain present in most active isoforms, produced one major band at 45 kDa (Figure 2A, top panel). Moreover, when the signal detection was carried out for longer times additional bands of lower intensity appeared at 37, 40, 56, 60 and 70 kDa (Figure 2A, central panel). Overall, samples from CN subjects generated bands of more intense signal than AD samples. This was confirmed by densitometry analysis which revealed that BACE1 levels were lower by 24%, 19%, 22%, and 21% for the bands at 37, 45, 56, and 70 kDa, respectively, in AD versus CN samples. Statistical significance was reached for these isoforms (Figure 2B). In addition, the BACE1 C-terminal antibody, which binds the intracellular domain of the BACE1 holoprotein, generated bands of very low intensity at 70 kDa after long signal detection only in a few CN samples (Figure 2A), suggesting that platelets contain only small amounts of transmembrane BACE1. Altogether, these data indicate that 1) multiple BACE1 isoforms are present in platelets; and 2) the levels of several platelet BACE1 isoforms are decreased in AD patients, providing an explanation for the ELISA data.

Figure 2.

Several BACE1 isoforms showed reduced levels in AD by Western blot.

(A) Western blots of all 27 samples for BACE1 and β-actin. The BACE1 N-terminal antibody detected a band of high intensity at 45 kDa detected by short exposure of autoradiographic films (30 sec; top panel), as well as bands of lower intensity at 37, 40, 45, 56, and 70 kDa requiring longer exposure times (5 min; central panel). The BACE1 C-terminal antibody detected a band of very low intensity in a few CN subjects (20 min exposure), likely corresponding to full-length BACE1 (see discussion). β-actin was used as a loading marker. (B) Densitometry analysis of the major BACE1 isoforms detected by Western blot (see C) with normalization to β-actin revealed that all these isoforms have lower levels in AD compared to CN platelet lysates. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we show that platelet BACE1 levels analyzed by a new BACE1 immunoassay were lower in AD versus CN subjects in a cross-sectional paradigm. These data were confirmed by the decreased levels of several BACE1 isoforms in AD samples by Western blot. BACE1 levels did not correlate to MMSE scores. However, the magnitude of the effect between CN and AD individuals on platelet BACE1 was large despite the relatively small sample size, suggesting that platelet BACE1 levels may serve as a peripheral biomarker for AD and could be analyzed in large cohorts using our new ELISA method.

The identification of specific, sensitive, safe, and inexpensive biomarkers for AD is a critical need defined more than two decades ago by the Reagan report [16]. We recently suggested peripheral BACE1 as a candidate [12], and demonstrated a good linearity for platelet BACE1 in our new immunoassay [13]. The use of platelet proteins as potential AD biomarkers was proposed some time ago because 1) blood is a tissue easy to collect; 2) platelets are present in large numbers in the blood; 3) APP and secretases are expressed in platelets [6]; and 4) platelets produce up to 95% of blood Aβ [7]. Previous studies have identified changes in APP and BACE1 isoform ratios between AD and CN platelets [9-11]. The present study not only shows the feasibility of using platelet BACE1 levels as an AD peripheral biomarker, but also provides evidence that our newly-developed ELISA might permit the safe and sensitive analysis of multiple samples at low cost in a short amount of time. However, further validation is needed to determine the discriminatory power of this new method for AD versus other neurological disorders. Furthermore, it will be important to investigate the effect of aging, anti-platelet medications, and other physiological and pharmacological factors on the performance of this BACE1 ELISA.

The decrease in total BACE1 levels noted by ELISA was underscored by the decreased levels of several isoforms identified by Western blot. Several bands we observed with the antibodies used here have not been described previously in platelets [10, 11]. However, we have recently reported the 45 and 70 kDa bands in platelet lysates [13], which are closed to the sizes of brain BACE1 isoforms [15] and indicating that the finding is reproducible. The difference in band sizes could be explained by the different antibodies used which likely recognize separate epitopes. In addition, we believe that our BACE1 N-terminal antibody recognizes most BACE1 isoforms since we observed similar bands in brain samples and recombinant human and mouse BACE1 proteins [13]. It should be noted that the detection of the band at 45kDa combined with the low intensity of the bands recognized by the BACE1 C-terminal antibody (Figure 1C) strongly suggests that the majority of platelet BACE1 isoforms do not bear a transmembrane domain, in contrast to brain BACE1. Moreover, the band at 70 kDa in platelets is likely a mixture of little amounts of full-length and a large quantity of BACE1, fully glycosylated, ectodomain isoforms. These observations provide grounds for the comprehensive analysis of platelet BACE1 isoforms to better understand the changes that may occur during disease progression, as well as any correlation between brain and blood BACE1 isoforms and levels which is currently unexplored.

In addition to the levels, one could ask whether BACE1 activity is also changed in AD platelets. Although such result would be of primary interest, current substrates and inhibitors poorly discriminate BACE1 from other beta-secretases (discussed in [12]), such as cathepsin D which is also expressed by platelets [17].

In conclusion, we believe that the data presented here, combined with previous reports, provide strong evidence that platelet BACE1 levels are worth exploring as a biomarker for AD. Future studies on larger populations and other neurodegenerative diseases, and including potential confounders such as platelet-affecting medications, ApoE genotype, and age would provide sensitivity and specificity data for the use of BACE1 levels as an AD biomarker. Moreover, platelet BACE1 levels could be used as a marker of the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions aimed at reducing BACE1 expression and activity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging grants R01AG034155 and P30AG019610-09.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koyama A, Okereke OI, Yang T, Blacker D, Selkoe DJ, Grodstein F. Plasma Amyloid-beta as a Predictor of Dementia and Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Molecular genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Ann Med. 2008;40:562–583. doi: 10.1080/07853890802186905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandalepas PC, Vassar R. Identification and biology of beta-secretase. J Neurochem. 2012;120(Suppl 1):55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Q, Li H, Gaddam SS, Justice NJ, Robertson CS, Zheng H. Amyloid precursor protein revisited: neuron-specific expression and highly stable nature of soluble derivatives. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2437–2445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.315051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evin G, Zhu A, Holsinger RM, Masters CL, Li QX. Proteolytic processing of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid precursor protein in brain and platelets. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:386–392. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen M, Inestrosa NC, Ross GS, Fernandez HL. Platelets are the primary source of amyloid beta-peptide in human blood. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:96–103. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Nostrand WE, Schmaier AH, Farrow JS, Cines DB, Cunningham DD. Protease nexin-2/amyloid beta-protein precursor in blood is a platelet-specific protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Luca M, Pastorino L, Bianchetti A, Perez J, Vignolo LA, Lenzi GL, Trabucchi M, Cattabeni F, Padovani A. Differential level of platelet amyloid beta precursor protein isoforms: an early marker for Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.9.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colciaghi F, Marcello E, Borroni B, Zimmermann M, Caltagirone C, Cattabeni F, Padovani A, Di Luca M. Platelet APP, ADAM 10 and BACE alterations in the early stages of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;62:498–501. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106953.49802.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang K, Hynan LS, Baskin F, Rosenberg RN. Platelet amyloid precursor protein processing: a bio-marker for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;240:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decourt B, Sabbagh MN. BACE1 as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(Suppl 2):53–59. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzales A, Decourt B, Walker A, Condjella R, Nural H, Sabbagh MN. Development of a specific ELISA to measure BACE1 levels in human tissues. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;202:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmeister A, Dietz G, Zeitschel U, Mossner J, Rossner S, Stahl T. BACE1 is a newly discovered protein secreted by the pancreas which cleaves enteropeptidase in vitro. JOP. 2009;10:501–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, Teplow DB, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, et al. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consensus report of the Working Group on: “Molecular and Biochemical Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease”. The Ronald and Nancy Reagan Research Institute of the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging Working Group. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sixma JJ, van den Berg A, Hasilik A, von Figura K, Geuze HJ. Immuno-electron microscopical demonstration of lysosomes in human blood platelets and megakaryocytes using anti-cathepsin D. Blood. 1985;65:1287–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]