Abstract

The hexahydro-1H-isoindolin-1-one core of muironolide A was prepared by asymmetric intramolecular Diels Alder cycloaddition using a variant of the MacMillan organocatalyst which sets the C4,C5 and C11 stereocenters.

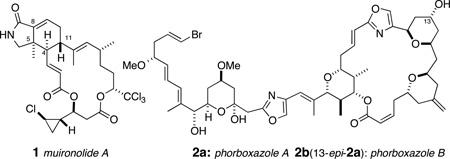

Marine invertebrates show an astounding repertoire of capabilities in biosynthesis of biologically active macrolides, a capacity likely owed to their associations with stable consortia of marine bacteria that augment biosynthetic expression and sequestration of natural products. Sponge-derived macrolides, like peloruside,1a and halichondrin B,1b have undergone preclinical or clinical trials as antitumor agents. Muironolide A (1)2 is an uncommon isoindolinone polyketide macrolide isolated from the same specimen of marine sponge, Phorbas sp., that earlier afforded phorboxazoles A and B (2a,b),3 and phorbasides A–E,4 F,5 and G–I.6

The nitrogenous polyketide 1 is rare in three ways: it is the singular representative of a natural product with an esterified trichloromethylcarbinol, embodying three ketide segments – two esters and an amide within a macrolide ring– and a rarely-encountered hexahydro-1H-isoindolin-1-one heterocycle (hereafter, referred to as an 'isoindolinone'). Muironolide A (1) is also scarce: the total yield from the only available specimen of Phorbas sp. was 90 µg. Although 1 shows activity against the pernicious fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans, the remaining amount of sample precludes further biological evaluation. Recollection of the sponge is not tenable (Phorbas sp. has not been encountered again by us or others7 since the original isolation of 2a and 2b), and total synthesis is the only feasible method to secure additional 1. We describe here the assembly of the stereo-complex hetero-bicyclic core 3 of muironolide A with control of all three stereocenters in the isoindolinone core of 1, through asymmetric catalysis.

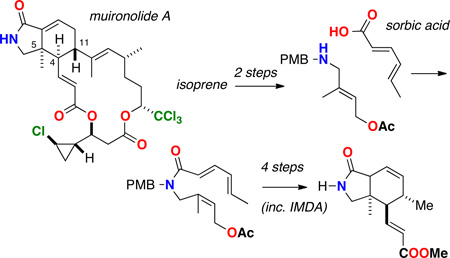

Inspection of the molecular structure of 1 reveals a potential biosynthesis based on assembly of three ketide units and formation of the isoindolinone core through an intramolecular Diels Alder (IMDA) reaction. The latter inspired a biomimetic approach which is outlined in Scheme 1, proceeding through the isoindolinone enoate ester 3 and the key cyclohexene carboxaldehyde 4, assembled from IMDA of 5.

Scheme 1.

Biomimetic approach to 1: retrosynthetic analysis.

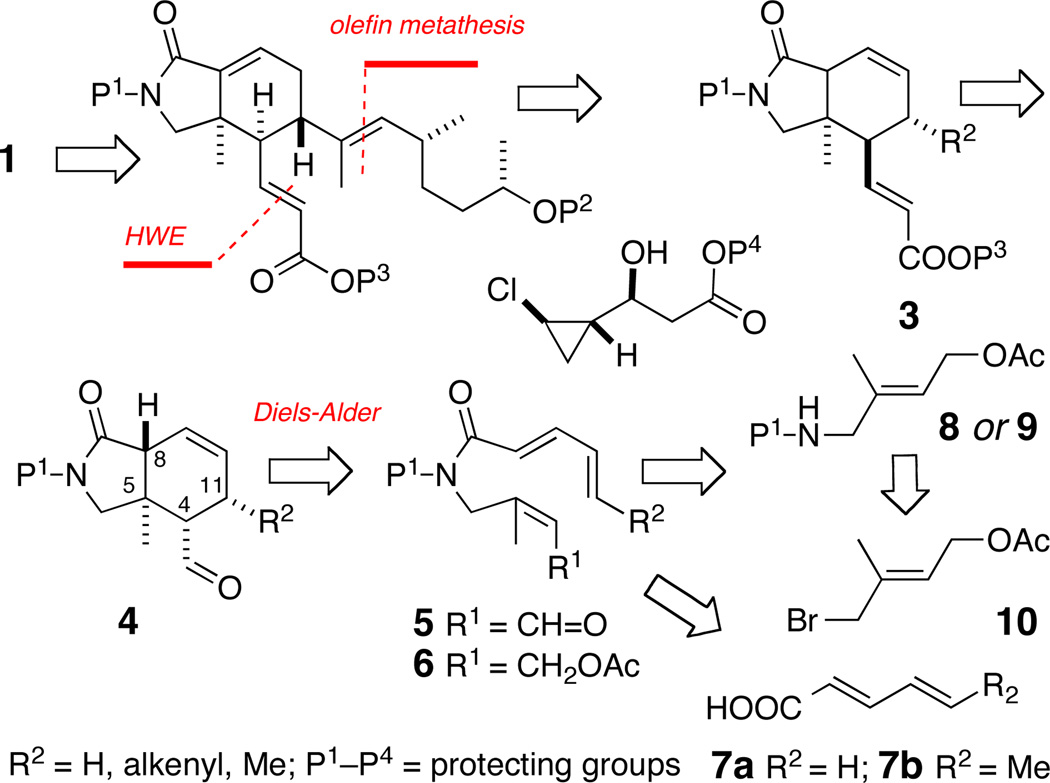

Compound 5, in turn, is elaborated from the open-ring allylic acetate ester 6, through intermediates 8–10, and pentadienoic acid (7a) or sorbic acid (7b). Asymmetry would be introduced by catalytic IMDA of 5 using MacMillan's imidazolidinones (Figure 1, 11a–c) which have been proven to promote [4+2] cycloadditions with high enantioselectivity.8

Figure 1.

MacMillan organocatalysts 11a,b (Ref 8) and Kristensen's derivative 11c (Ref 17).

We anticipated the role of the N-protecting group P1 (viz. 5, Scheme 1) would be critical for two reasons: ease of removal near completion of 1, but primarily to provide steric bias to populate the s-cis rotamer of tertiary amide, necessary to achieve the DA transition state. Control of the three stereocenters C4, C5 and C11 in the isoindolinone rings of 1 would follow from the consequences of the endo rule and base-promoted epimerization at C49 (c.f. 4, Scheme 1).

These three objectives were realized through the completion of two pilot syntheses of model isoindolinones – racemic (±)-12a and optically enriched (5R)-4 – as described below.

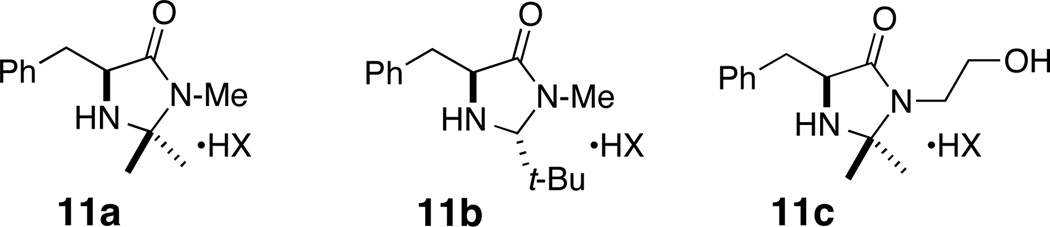

The dienophile precursor, 8 (Scheme 2), for the IMDA reaction was prepared from allylic bromide 1010 by SN2 displacement with p-methoxybenzylamine under conditions11 (Cs2CO3, DMF) that select for the monoalkylated product (95%). Diene components – pentadienoic acid (7a)12 and commercially available sorbic acid (7b) – were separately coupled with 8 and 9 to give tertiary amides 6a,b in good yields (73% and 80%, respectively). Thermal IMDA of 6a (toluene, 110 °C) gave only sluggish conversion to the racemic cycloaddition product (±)-6a. In contrast, microwave-promoted reaction of 12a (200 °C, chlorobenzene, 30 min), in the presence of a radical inhibitor, gave smooth conversion to (±)-12a in very good yield (86%) but with poor diastereoselectivity (1:2 trans to cis). When the product was redissolved in ethanol and subjected to microwave conditions (120 °C), product 12a (dr ~1:2) equilibrated completely to cis-12a (dr > 30:1). Formation of the predominantly cis-product suggested α-epimerization of 12a, similar to that observed during IMDA of allylic sorbates to bicyclic γ- butyrolactones.13 The stage was set to explore optimzed conditions for asymmetric IMDA.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of isoindolinones (±)-12a and 4a–c by intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition (IMDA).

aprepared from the acid chloride of 7b. byield over two steps.

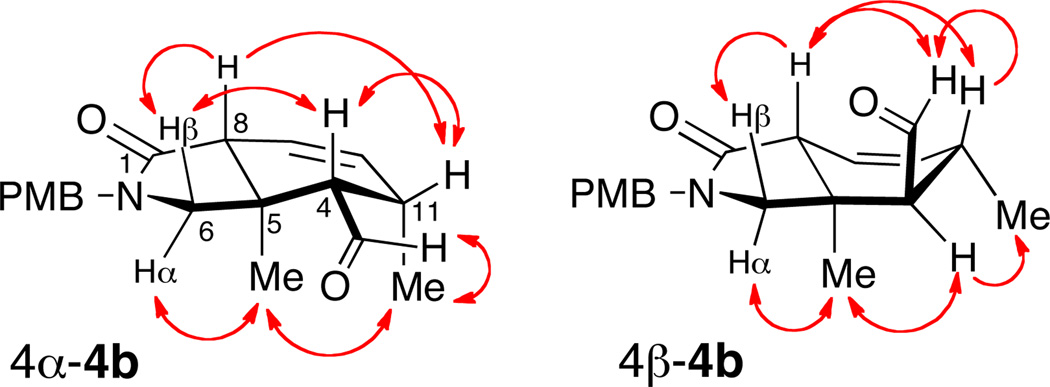

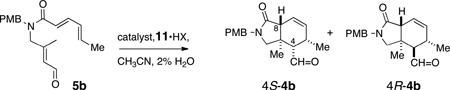

The precursor asymmetric IMDA was prepared in two steps by methanolysis (K2CO3, MeOH) of the acetate ester 6a to the corresponding allylic alcohol which was oxidized (MnO2, CH2Cl2) to aldehyde 5a14 in good overall yield (53% over two steps). Exposure of 5a to either catalyst 11a or 11b (Scheme 2) gave slow [4+2] cycloaddition, a disappointing yield of cycloadduct 4a (~4%) and poor recovery of starting material, probably due to the tendancy of the diene to polymerize.15 Reasoning that a terminally-substituted diene may fare better in the IMDA, aldehyde 5b was prepared using the same sequence of reactions and replacement of pentadienoic acid with sorbic acid 11b. In the presence of catalyst 11b, aldehyde 5b underwent clean asymmetric IMDA in good yield (Table 1, Entry 2, 84%), exclusively in endo mode, to give mostly (+)-(4S,5R,8R)- 4b16 with a lesser amount of (4R,5R,8R)-4b (dr >20:1), albeit in modest enantiomeric excess (42% ee). The relative configurations of the separated pure isomers (HPLC) were determined from extensive 1D-NOE experiments (Figure 2 and Supporting Information).

Table 1.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst 11•HXa | temp, °C | time, h | yield, %b | drc 4S-4b:4R-4b | % eed | |

| 1 | 11a | HCl | 23 | 72 | 5 | 1.6:1 | 14 |

| 2 | 11b | HClO4 | 23 | 4.5 | 84 | >20:1 | 42 |

| 3 | 11b | HClO4 | 10 | 57 | 60 | 6:1 | 50 |

| 4 | 11c | HCl | 23 | 36 | 38 | 1.1:1 | 10 |

| 5 | 11c | HClO4 | 23 | 40 | 73 | 3.8:1 | 72 |

| 6 | 11c | CF3COOH | 23 | 39 | 25 | 2.6:1 | 78 |

| 7 | 11c | HClO4 | 23 | 6 | 48 | 10:1 | 52 |

| 8 | 11c | CF3COOH | 23 | 18 | 86 | 3.4:1 | 36 |

| 9 | 11c | HClO4 | 0 | 84 | 73 | 6:1 | 88 |

| 10 | 11c | HClO4 | 10 | 48 | 69 | 4:1 | 71 |

| 11 | none | – | 80 | 90 | 83e | 3.2:1 | –f |

20 mol% catalyst, CH3CN, 2% H2O, [5b] = 0.5 M.

Combined isolated yield of 4S- and 4R-isomers.

From 1H NMR integrations.

% ee of major isomer, determined by chiral HPLC (Chiracel OD, 3:7 i-PrOH-hexane).

carried out in toluene.

racemic product.

Optimization of the asymmetric IMDA (Table 1) was undertaken and, similar to observations by MacMillan,8 it was found that the catalyst structure, counterion, and temperature all played important roles in affecting the yield, diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity. Catalyst 11a (HCl salt) gave poorer yields of 4b (Entry 1, 5%), even after 72 h. A slight gain in enantioselectivity in formation of the major epimer 4S-4b (Entry 3, 50% ee) was seen with catalyst 11b (HClO4 salt) when the temperature was lowered from 23 °C to 10 °C, however, at the expense of lower yield, diastereoselectivity (60%, dr 6:1) and reaction time (57 h instead of 4.5 h).

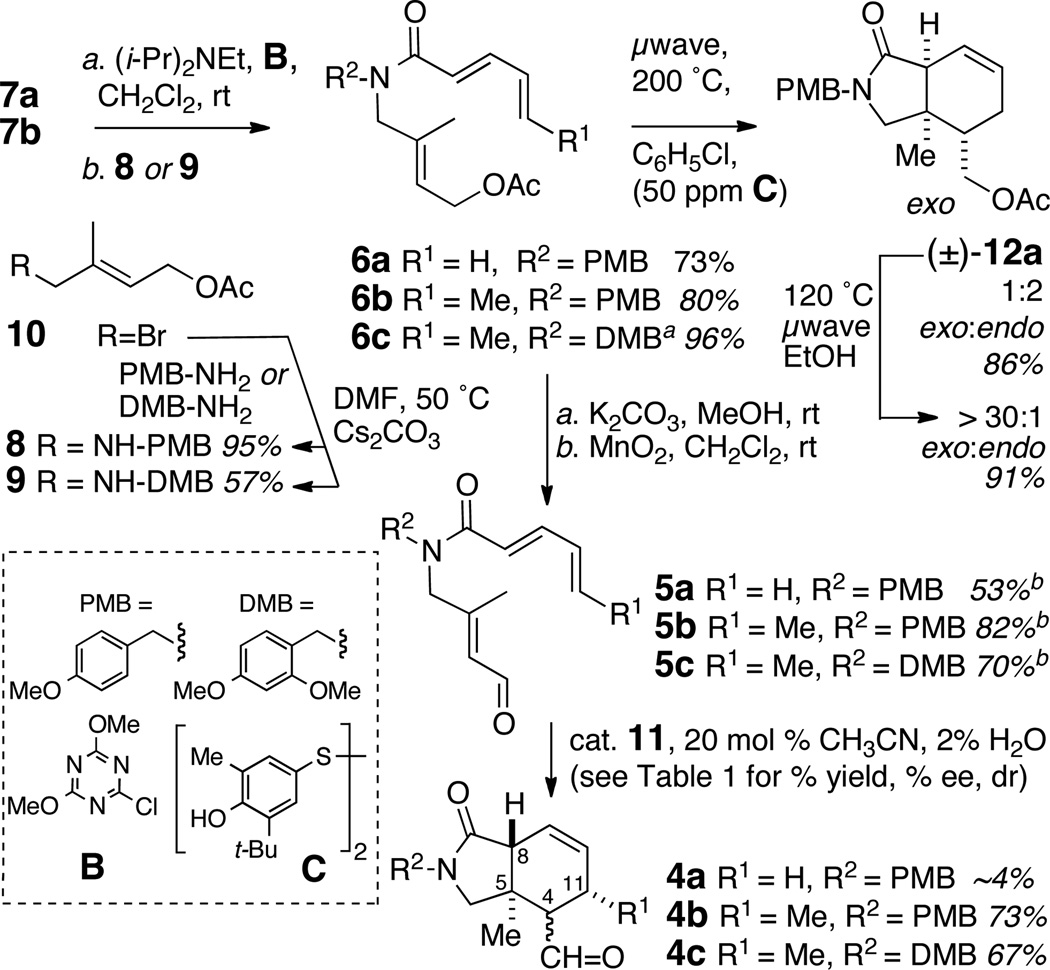

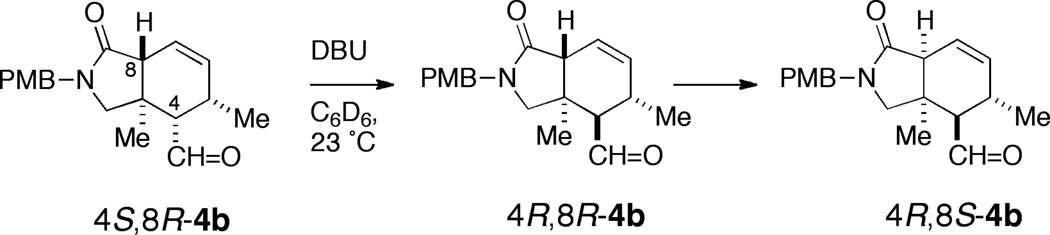

Gratifyingly, N-(2-hydroxy-1-ethyl)-imidazolidone 11c, a MacMillan-type catalyst reported by Kristensen and coworkers17 as an intermediate in the preparation of copolymer-supported catalysts, gave the best outcomes.18 Under conditions similar to those used with 11b (Entry 2), IMDA of 5b in the presence of 11c (20 mol %, 23 °C, Entry 5) gave (+)-4b with almost double the enantioselectivity (72% ee), albeit with lower diastereoselectivity (73%, dr = 3.8:1). Optimal conditions for IMDA of 5b (Entry 9, 20 mol% 11c, 0 °C, 73 h) gave 4b (84% yield, dr = 6:1, 88% ee).19 Base treatment of 4b (DBU, C6D6, 23 °C, 13 h, Scheme 3) epimerized C4 and inverted the 4R:4S ratio to >20:1 in favor of the configuration required for 1.20 Thus, pure (+)-(4R,5R,8S,11S)-4b was obtained in 70% yield over two steps after preparative HPLC.

Scheme 3.

Base-promoted isomerization of (4S,8R)-4b.

The steric bulk of the N-protecting group influences the outcome of the IMDA reaction through torsional strain that also populates the required s-cis conformation of the tertiary amide. Replacement of the N-PMB protecting group with a 2,4-dimethoxybenzyl group (N-DMB) was investigated to determined the effect on yield, enantio- and stereo-selectivity. Compound 5c, prepared from 9 using a similar sequence for 5b, was treated with 11c (20 mol%, 3 °C, 54 h) to afford 4c in 67% yield, with slightly lower enantioselectivity (84% ee) but with high 4S:4R diastereoselectivity (dr >20:1).21

The kinetics of base-equilibration of purified (4S,8R)-4b (DBU, C6D6, 23 °C, Scheme 3 and Supporting Information) were briefly investigated. 1H NMR revealed rapid conversion of the (4S,8R)-4b to the more stable isomer (4R,8R)-4b,22 and finally, slower conversion of the latter to a third isomer, (4R,8S)-4b.

At equilibrium in C6D6 (12 h), (4S,8R)-4b was absent and the relative concentration of (4R,8R)-4b to (4R,8S)-4b was 2:1. Interestingly, very rapid epimerization of C4 was observed with NaH (DMF, 23 °C, 15 min) with complete conversion of (4S,8R)-4b to a mixture of (4R,8R)-4b and (4R,8S)-4b (dr = 4:1). Deuterium incorporation studies (NaOCD3, CD3OD) confirmed that H4 was rapidly exchanged for D followed by slower replacement of H8, consistent with the higher pKa of the H8 in the β,γ-unsaturated lactam.

No conjugated double bond isomers of 4b were detected under any of the isomerization conditions tried (NaOMe-MeOH, DBU-benzene, NaH-DMF). Attempted kinetic trapping of the dienolate generated from 4b with strong base (KHMDS, −78 °C; 1 equiv CH3COOH) returned only starting materials as a mixture of C4 and C8 epimers.23,24 From these results, we deduced that enolization of the IMDA product occurred by deprotonation-reprotonation at C8, but the β,γ-double bond isomer is more stable than the conjugated isomer.25

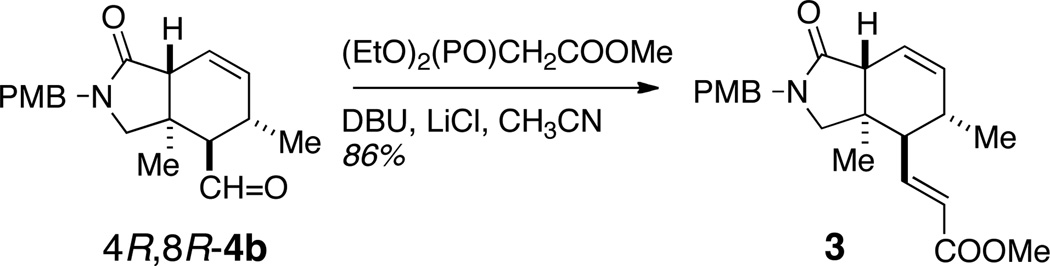

Finally, aldehyde 4b was chain-extended (Scheme 4) by Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction under Roush-Masamune conditions26 to give exclusively E-3 in 86% yield.

Scheme 4.

Chain extension of aldehyde (4R,5R,8R,11S)-4b.

In summary, a simple stereocontrolled route to 3, embodying the isoindolinone core of muironolide A (1), was achieved by asymmetric intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition of an acyclic trienal precursor catalyzed by 11c.

Efforts towards extending the IMDA approach to completion of 1 are underway in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

1D-NOE of (4S)- and (4R)- isomers of 4b (mixing time, tm = 400 mS). Numbering follows that of 1 (see Ref 2).

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Morinaka for assistance with NMR measurements, J. Pigza for helpful discussions, J. Haeckl and B. Ruby for preparation of some catalysts and intermediates, Y. Su for HRMS measurements (all UCSD), and R. New (UC Riverside) for additional MS data. The 500 MHz NMR spectrometers were purchased with a grant from the NSF (CRIF, CHE0741968). This work was supported by the NIH (AI-039987, CA-122256).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) West LM, Northcote PT, Battershill CN. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:445. doi: 10.1021/jo991296y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bai RL, Paull KD, Herald CL, Malspeis L, Pettit GR, Hamel E. J. Bioc. Chem. 1991;266:15882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalisay DS, Morinaka BI, Skepper CK, Molinski TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;31:7552. doi: 10.1021/ja9024929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Searle PA, Molinski TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8126. [Google Scholar]; (b) Searle PA, Molinski TF, Brzezinski LJ, Leahy JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:9422. [Google Scholar]; (c) Molinski TF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7879. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) MacMillan JB, Xiong-Zhou G, Skepper CK, Molinski TF. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3699. doi: 10.1021/jo702307t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Skepper CK, MacMillan JB, Zhou GX, Masuno MN, Molinski TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4150. doi: 10.1021/ja0703978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) MacMillan JB, Xiong-Zhou G, Molinski TF. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3699. doi: 10.1021/jo702307t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalisay DS, Molinski TF. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:739. doi: 10.1021/np900009b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalisay DS, Molinski TF. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:679. doi: 10.1021/np1000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Capon RJ, Skene C, Liu EH, Lacey E, Gill JH, Heiland K, Friedel T. Nat. Prod. Res. 2004;18:305. doi: 10.1080/14786410310001620619. This report of occurrence of 2a,b in a sponge identified as Raspailia sp. from the Indian Ocean some 1200 km south of the site of collection of Phorbas sp. provokes the intriguing speculation that the two sponges are one and the same, and that Raspailia sp. may contain 1.

- 8.(a) Wilson RM, Jen WS, MacMillan D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11616. doi: 10.1021/ja054008q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ahrendt KA, Borths CJ, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4243. [Google Scholar]

- 9.IMDA of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes with MacMillan organocatalysts does not always conserve the α,β-relative configuration of the starting trienal. Ref 8

- 10.Prepared by 1,4-addition of the elements of Br and OAc to isoprene (NBS, AcOH). Babler JH, Buttner WJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:239.

- 11.(a) Salvatore RN, Nagle AS, Schmidt SE, Jung KW. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1893. [Google Scholar]; (b) Salvatore RN, Nagle AS, Schmidt SE, Shin SI, Nagle AS, Worrell JH, Jung KW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9705. [Google Scholar]; (c) Salvatore RN, Nagle AS, Jung KW. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:674. doi: 10.1021/jo010643c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Idoux JP, Ghane H. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1979;24:157. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jessup PJ, Petty CB, Roos J, Overman LE. Organic Syntheses. 1988;6:95. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Wu J, Yu H, Wang Y, Xing X, Dai W-M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:6543. [Google Scholar]; (b) Guy A, Lemaire M, Guiette M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:3575. [Google Scholar]; (c) Boeckman RK, Jr, Demko DM. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:1789. [Google Scholar]; (d) Martin SF, Williamson SA, Gist RP, Smith KM. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:5170. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contained ~5–10% of the Z-isomer.

- 15.Inclusion of a radical inhibitor C (Scheme 1) did not suppress formation of polymer; therefore, the mechanism of polymerization is likely ionic in nature.

- 16.The absolute configuration follows from the expected sense of asymmetric induction demonstrated by McMillan and coworkers. Ref 8.

- 17.Kristensen TE, Vestli K, Jakobsen MG, Hansen FK, Hansen T. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:1620–1629. doi: 10.1021/jo902585j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catalyst 11c is more conveniently prepared from L-phenylalanine methyl ester and inexpensive ethanolamine than 11a,b which requires the more expensive, 'controlled substance', MeNH2.

- 19.The hydroxyethyl side chain in 11c may play an important role in stabilizing either the transition state by hydrogen bonding, or through intramolecular nucleophilic capture of the incipient iminium ion.

- 20.The relative configurations of (4S,8R)-4b and (4R,8R)-4b were assigned by 1D NOESY studies.

- 21.See Supporting Information, Table S1 for optimization of conditions for IMDA of 5c to give 4c.

- 22.The cyclohexene ring conformation changed to a pseudo-boat.

- 23.Clearly, the biosynthesis of 1 favors the α,β-unsaturated lactam. Models show that the macrolide ring adopts a 'ring flipped' cyclohexene half-chair compared to models of 4b in which the C4 and C5 substituents are held in the pseudo-equatorial orientation, which may favors the conjugated lactam.

- 24.Alternative methods can be used to move the C=C double bond into conjugation with the lactam C=O as required for 1 (e.g. hydrogenation α-selenation, followed by H2O2 oxidation-selenoxide elimination).

- 25.Molecular modeling and semi-empirical calculations (PM3) of enthalpies of formation of models of 4 (the N-protecting group was removed for simplicity) show that the non-conjugated isomers are disfavored over the α,β-conjugated isomers by ~1 kcal.mol−1.

- 26.Blanchette MA, Choy W, Davis JT, Essenfeld AP, Masamune S, Roush WR, Sakai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:2183. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.