Abstract

Objective

Intravenous NMDA antagonists have shown promising results in rapidly ameliorating depression symptoms, but placebo-controlled trials of oral NMDA antagonists as monotherapy have not observed efficacy. We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT00344682) of the NMDA antagonist memantine as an augmentation treatment for patients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder.

Method

31 participants with partial or nonresponse to their current antidepressant were randomized (from 2006–2011) to add memantine (flexible dose 5–20 mg/day, with all memantine group participants reaching the dose of 20 mg/day) (n= 15) or placebo (n= 16) to their existing treatment for 8 weeks. The primary outcome, change in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Score (MADRS), was evaluated with repeated measures mixed effects models using last-observation-carried-forward methods. Secondary outcomes included other depression and anxiety rating scales, suicidal and delusional ideation, and other adverse effects.

Results

Participants receiving memantine did not show a statistically or clinically significant change in MADRS scores compared to placebo, either over the entire study (β=0.133, favoring placebo, p=0.74) or at study completion (week 8 MADRS score change: −7.13 +/−6.61 (memantine); −7.25 +/−11.14 (placebo), p=0.97). A minimal-to-small effect size (comparing change to baseline variability) was observed (d=0.19), favoring placebo. Similarly, no substantial effect sizes favoring memantine, nor statistically significant between-group differences, were observed on secondary efficacy or safety outcomes.

Conclusions

This trial did not detect significant statistical or effect size differences between memantine and placebo augmentation among nonresponders or poor responders to conventional antidepressants. While the small number of participants is a limitation, this study suggests memantine lacks substantial efficacy as an augmentation treatment against major depressive disorder.

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) antagonists have garnered intense interest as a novel therapy for depression since the pivotal findings that ketamine infusions produce rapid, robust, and sustained improvement in depression symptoms.1, 2 However, ketamine’s use is limited by the requirement for intravenous administration, the transient dissociative and perceptual disturbances that frequently accompany its administration,3 and the challenges of preserving recovery of symptoms over longer than a few weeks after a single infusion.4 The NMDA antagonist memantine, while of lower affinity, faster-dissociating, and exhibiting other pharmacological differences than ketamine,5 also has fewer side effects and is orally administered. Memantine is also already approved by the US FDA for treatment of another neuropsychiatric disorder, Alzheimer’s dementia, making it an attractive candidate for investigation.

An initial trial of memantine as monotherapy for depression was terminated early when memantine treatment failed to separate from placebo based on response or remission rate.6 Although this monotherapy trial did not demonstrate benefit, there are animal findings suggesting that noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists such as memantine work synergistically in combination with antidepressants,7 providing a rationale for evaluating memantine specifically as an augmentation treatment. In this paper we report the results of a randomized trial testing the hypothesis that memantine would have greater efficacy than placebo in reducing symptoms of major depressive disorder when used to augment antidepressant treatment.

METHOD

We conducted an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT00344682) of memantine augmentation treatment of outpatients at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts from July 2006 to December 2011. Participants who were incomplete or nonresponders to their current antidepressant were randomized 1:1 to add on either flexibly-dosed memantine, 5mg–20mg/day, or placebo to their current antidepressant using a block randomization design by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Investigational Pharmacy. A printed list computer-generated from the website www.randomization.com was used with allocation concealed from participants, research staff, and investigators. All participants began on 5 mg/day and the dose was increased by 5mg/day at weekly intervals as tolerated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/day. In the absence of limiting adverse effects, this dose was achieved approximately 22 days into the eight-week (56-day) trial.

The original target recruitment was 25 patients per study arm. However, the study was terminated prior to full enrollment in 2012 at funder request, resulting in a final enrollment of 31 patients. The study was approved by the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Study participants were recruited through clinician referral and posted and radio advertising with the majority of patients recruited through clinician referral within our single-site, tertiary-care medical center. Inclusion criteria included adults aged 18 to 85 years, the ability to provide written informed consent, diagnosis of a current or partially remitted Major Depressive Episode by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR)9 criteria using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Diagnostic Interview,10 and a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score (17-item)11, 12 of ≥16. Participants received one of the following medications at the following stable dosages for the previous 25 days or more prior to study entry: mirtazapine (≥15 mg/day), fluoxetine, paroxetine, or citalopram (≥20 mg/day), paroxetine controlled-release (≥25 mg/day), sertraline or desvenlafaxine extended-release (≥50 mg/day), duloxetine (≥60 mg/day), fluvoxamine extended-release (≥100 mg/day), venlafaxine or venlafaxine extended-release (≥150 mg/day), fluvoxamine (≥200 mg/day), bupropion or bupropion sustained-release (≥300 mg/day). These dosages were based on “adequate treatment” definitions drawn from the Antidepressant Treatment History form13 except for paroxetine controlled-release, fluvoxamine extended-release, desvenlafaxine extended-release, and duloxetine. For these antidepressants, approximately comparable dosages were determined by the study investigators. Participants were not permitted to make antidepressant dosage changes during the eight weeks of trial participation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any study assessments.

Exclusion criteria included a Diagnosis and Statistical Manual-IV Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)9 diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, current mood stabilizer or antipsychotic use (except lithium as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder), a history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence within 6 months prior to study enrollment, a history of electroconvulsive therapy within 3 months prior to study enrollment, a history of seizures, Mini-Mental Status Exam score of <21 (indicating moderate dementia14), or active suicidal ideation, defined as either a score of 2 on either item 4 or 5 of the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI)15 or a score of 3 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms Self Report scale (QIDS-SR) suicidal thoughts item.16 To maximize generalizability, only medications clearly contraindicated for use with memantine (e.g., other NMDA antagonists, such as amantadine or dextromethorphan) were restricted. There were no restrictions on established anxiolytic or insomnia treatments, or upon initiation or continuation of psychotherapy. Pre-specified criteria for termination of participation in the trial (“rescue criteria”) were as follows: occurrence of a score of 3 on the QIDS-SR suicidal thoughts item, or a score of 5 or 6 on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)8 suicidal thoughts item (Item 10), a worsening of >35% on MADRS score from baseline, or active alcohol abuse or illicit substance use.

Procedures

Patients were evaluated by a research psychiatrist and a research coordinator at each study visit. Study drug and placebo were dispensed from the investigational pharmacy. Participants were evaluated at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 using the MADRS and the self-rated QIDS-SR. Adverse events were recorded at each visit. At baseline and weeks 4 and 8, the Hamilton Anxiety scale (HAM-A)17 and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS)18 delusional severity item were also administered. At baseline and 8 weeks, and as needed during the protocol, the SSI was administered. Brief (approximately 45 minutes) cognitive testing was also performed at baseline and week 8 (results not reported here).

After completion of the trial, participants were provided with a tapering of their study drug over 1–3 weeks. All patients, research staff, and clinical investigators remained blinded throughout the trial with the exception of an unintentional unblinding of one of the principal investigators (EGS) for a single participant receiving placebo who had completed the trial.

Statistical Analysis

T-tests, and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, were used to describe demographic and clinical differences between the two treatment groups. The primary outcome was change in MADRS score over repeated measures (one baseline and six treatment assessments), using participants’ most recently observed MADRS scores for any missing assessments through study completion at eight weeks (“Last Observation Carried Forward” [LOCF]). Secondary depression outcomes included change over repeated measures in MADRS score, using no imputation (“Observed Case” analysis) (i.e., all available observations used but no values were imputed for missing values), and QIDS-SR score (LOCF). Each analysis used intent-to-treat, repeated measures mixed effects models with random intercepts and random slopes. Other secondary efficacy outcomes included change in HAM-A scale (LOCF) and MADRS response rate (defined as 50% change in MADRS score from baseline) and remission rate (defined as a MADRS score of 12 or less) at week 8, analyzed by Fisher’s exact tests. Safety analyses included change in the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) and SADS Delusional Scale, comparing baseline score to the maximum score obtained during treatment.

Results of “guess tests” (i.e., guesses of treatment assignment made after trial completion) were analyzed by Fisher’s exact tests. All tests were two-tailed, considered significant at alpha = 0.05, and conducted using Stata/IC 12.1 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), except the power estimates (STATA 9.2 for PC). Statistical power (alpha=0.05, beta=0.80) was estimated post hoc in terms of projected detectable effect size using estimates of mean changes, standard deviations, and correlations between observations from the data we obtained using an alternate repeated measures design, repeated measures Analysis of Covariance.

RESULTS

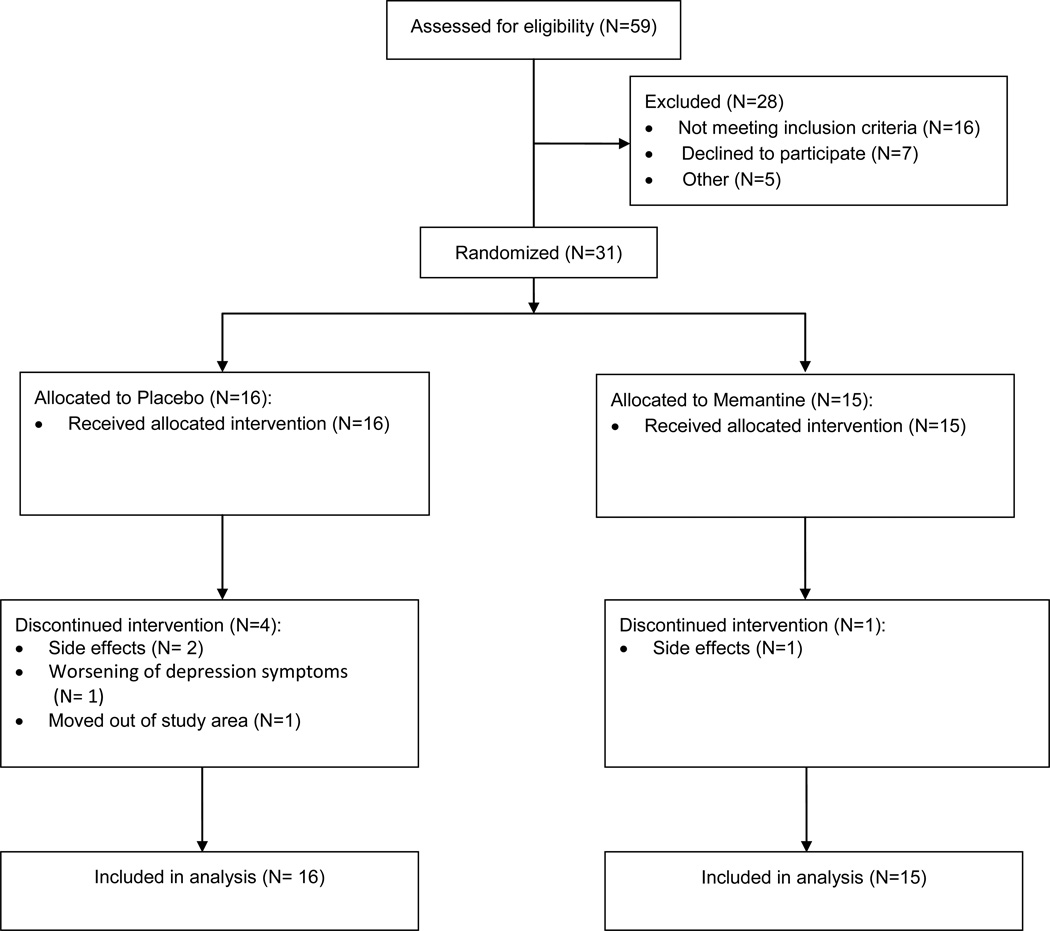

Of 59 patients screened by phone or in person, 31 (53%) were randomized to receive memantine (n=15) or placebo (n=16). All randomized participants received study medication and had at least 2 post-baseline assessments, and 84% of the participants completed the trial (Figure 1). 100% of memantine and 50% of placebo recipients received a study medication dose of 20 mg/day during some portion of the trial. One participant receiving memantine dropped out of the protocol for side effects, while four participants receiving placebo dropped out of the protocol for side effects, worsening of depression symptoms, or movement out of the area. Although study enrollment was terminated early, randomization balanced patients effectively on all measured confounders (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Screening, Randomization, and Disposition of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Incompletely Responding to Antidepressant Therapy Randomly Assigned to Treatment Augmentation with Memantine or Placebo

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Assigned Memantine or Placebo Augmentation of Antidepressant Treatment

| Characteristic | Memantine Augmentation (N = 15) Mean, (S.D.)a |

Placebo Augmentation (N = 16) Mean, (S.D.)a |

P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Gender (Female) (n, %) | 8 (53.33) | 11 (68.75) | 0.473 |

| Age, years | 54.8 (6.17) | 49.75 (11.68) | 0.147 |

| Education, yearsc | 13.82 (2.44) | 14.78 (2.28) | 0.380 |

| Physiological Measures | |||

| BMId | 28.41 (5.34) | 27.98 (4.82) | 0.834 |

| Baseline & Concomitant Antidepressant Treatmente | |||

| SSRIs | 10 (66.67) | 11 (68.75) | 1.000 |

| Citalopram/Escitalopram | 5 (33.33) | 4 (25.00) | 0.704 |

| Fluoxetine | 4 (26.67) | 2 (12.50) | 0.394 |

| Fluvoxamine | 0 (0) | 1 (6.67) | 1.000 |

| Paroxetine | 0 (0) | 2 (12.50) | 0.484 |

| Sertraline | 1 (6.67) | 2 (12.50) | 1.000 |

| SNRIs | 3 (20.00) | 4 (25.00) | 1.000 |

| Duloxetine | 2 (13.33) | 1 (6.25) | 0.600 |

| Venlafaxine/Desvenlafaxine | 1 (6.67) | 3 (18.75) | 0.600 |

| Bupropion | 4 (26.67) | 3 (18.75) | 0.685 |

| Mirtazepine | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Tricyclic Antidepressantf | 2 (13.33) | 0 (0.00) | 0.226 |

| Desipraminef | 2 (13.33) | 0 (0.00) | 0.226 |

| Combination Treatment (Receiving >1 Antidepressant) | 4 (26.67) | 3 (18.75) | 0.685 |

| ≥ Minimum Adequate Doseg | 10 (66.67) | 12 (75.00) | 0.704 |

| Length of Preceding Antidepressant Treatmenth | |||

| ≤ 3 months | 2 (of 12) (16.67) | 1 (of12) (8.33) | 1.000 |

| ≤ 12 months | 6 (of12) (0.50) | 3 (of12) (0.25) | 0.400 |

| Other Psychiatric Medications (intended to treat Depression) | |||

| Dopaminergic Stimulants | 1 (6.67) | 2 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Non-Dopaminergic Stimulants | 1 (6.67) | 2 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Clinical Rating Scales (Baseline) | |||

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17-item) | 22.60 (4.73) | 21.69 (5.47) | 0.624 |

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale | 27.47 (8.32) | 27.38 (6.95) | 0.974 |

| Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (Self-Report) | 15.73 (7.01) | 12.31 (4.16) | 0.107 |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scalei | 23.33 (6.81) | 24.07 (9.17) | 0.805 |

| Mini-Mental Status Exam | 29 (1.51) | 28.87 (1.13) | 0.786 |

| Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation | 2.27 (4.33) | 1.63 (3.07) | 0.636 |

Data presented as mean and standard deviation [mean, (standard deviation)] except for gender and antidepressant medication information, presented as count and percent [number, (percent)].

Calculated by t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables

Data missing for 11 participants: 4 assigned to memantine and 7 assigned to placebo.

Data missing for 5 participants: 2 assigned to memantine and 3 assigned to placebo.

Since antidepressant treatment at baseline was maintained through study, the same Table information applies to antidepressant treatment received throughout the study. Percentages do not equal 100% since some participants were receiving more than one antidepressant.

Participants were required to be receiving a non-TCA antidepressant, but two patients received desipramine in combination with a non-TCA antidepressant.

Determined as the length of time the participant had been receiving their antidepressant of longest duration.

Data missing for 7 participants, 3 assigned to memantine and 4 assigned to placebo.

Data missing for 1 participant, assigned to placebo.

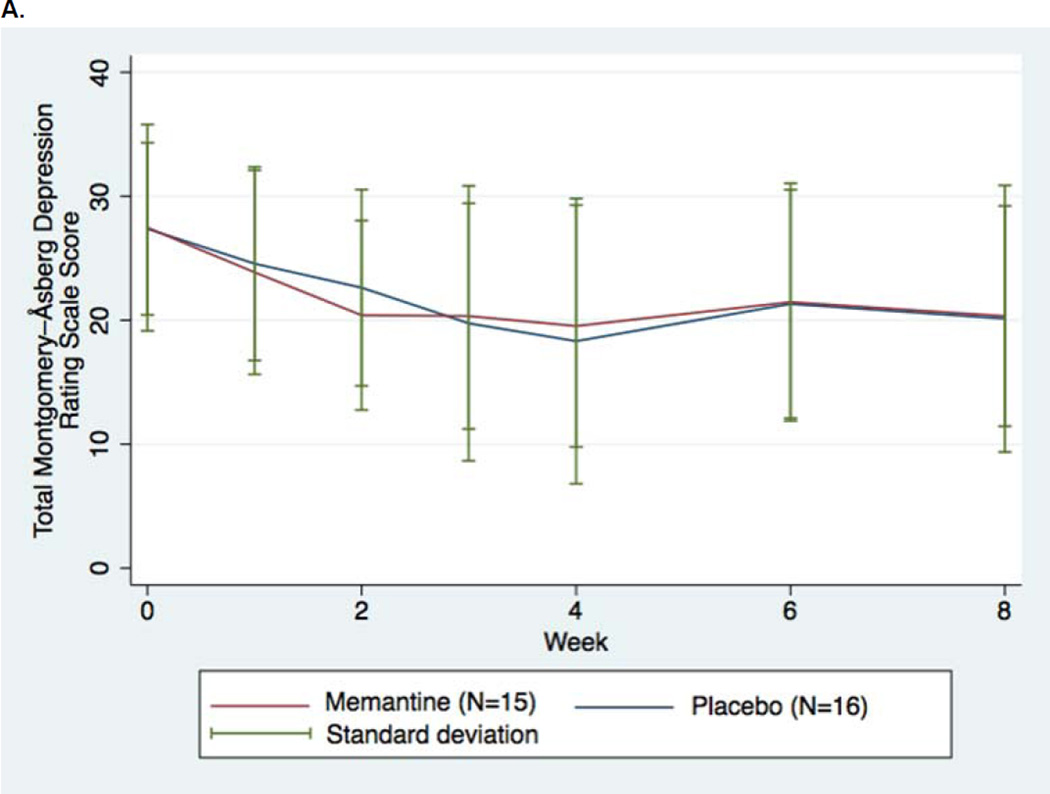

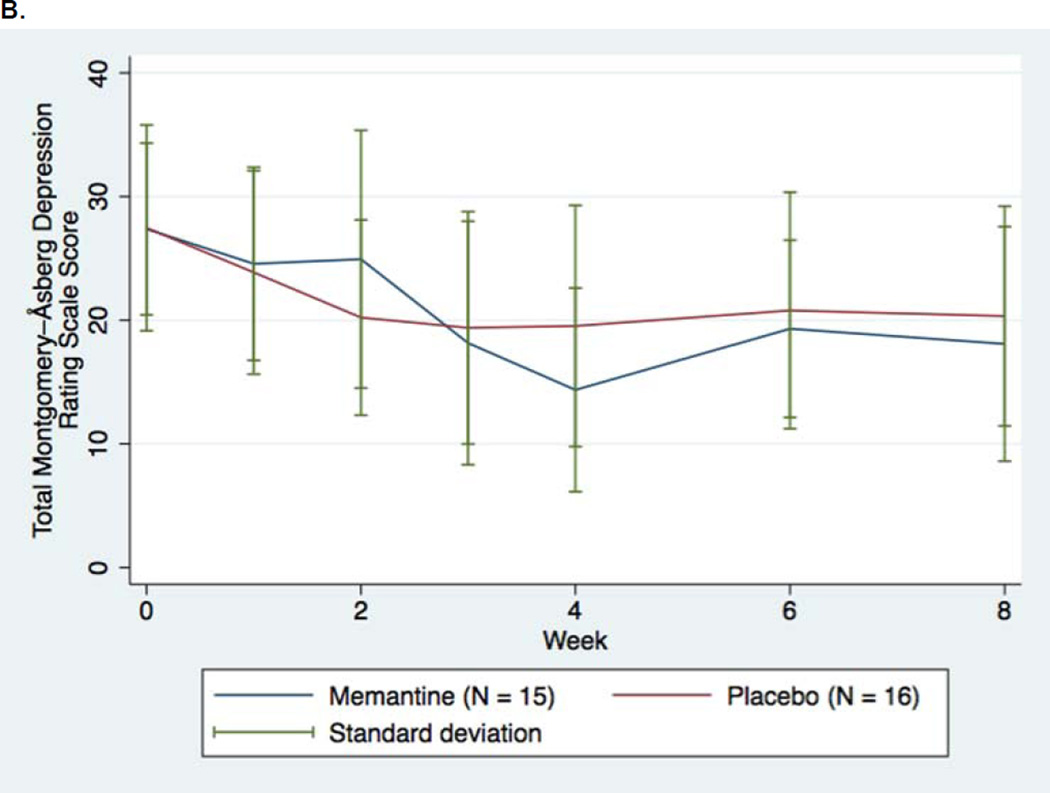

No significant differences were found between memantine augmentation and placebo augmentation in our primary endpoint of change in MADRS score (LOCF) across all the repeated measures, (beta =0.133, p= 0.74) using LOCF methods (Table 2A), with the nonsignificant and modest score differences observed favoring placebo (Figure 2A). An alternative, “observed case” analysis of the data was also nonsignificant (beta= 0.497, p=0.212) (Figure 2B).

TABLE 2.

| A. Results of Mixed Effects Models for Patients Assigned Memantine or Placebo Augmentation of Antidepressant Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Coefficienta | P-Valueb | ||

| Primary Outcome | |||

| Model for the Change in MADRS Score (LOCF)c (Time × Treatment interaction) | 0.133e | 0.742 | |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Model for the Change in MADRS Score (Observed Case Analysis)d Time × Treatment interaction | 0.497f | 0.212 | |

| Model for the Change in QIDS Score (LOCF)c Time×Treatment interaction | −0.246g | 0.216 | |

| B. Changes in and Effects Sizes of Rating Scale Scores at Week 8 for Participants Assigned Memantine or Placebo Augmentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in Rating Scale Score (Participant’s Final Score minus Baseline Score) |

Effect Size c | |||

| Rating Scale (Analysis) | Memantine Augmentation (N=15) |

Placebo Augmentation (N=16) |

P Valueb | |

| Mean, (S.D.)a | Mean, (S.D.)a | |||

| Primary Outcome | ||||

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (LOCF)d,e | −7.13 (6.61) | −7.25 (11.14) | 0.97 | 0.19 |

| Secondary Depression Outcomes | ||||

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (Observed Case)f | −7.13 (6.61) | −10.75 (10.46) | 0.28 | 0.69 |

| Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms-Self Report (LOCF)d, | −6.47 (5.25) | −3.69 (5.00) | 0.14 | −0.04 |

| Secondary Anxiety Outcome | ||||

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (LOCF)d,g | −4.13 (5.11) | −5.53 (7.29) | 0.55 | 0.00 |

Negative coefficient = greater decrease in the memantine group compared to the placebo group; Positive coefficient = greater decrease in the placebo group compared to the memantine group.

Significance of Treatment*Time interaction term.

LOCF = Last Observation Carried Forward

Observed case = all rating scale observations used, but observations not carried forward (i.e., no imputation).

The full model including this interaction term was: 24.669− 0.551*TreatmentGroup − 0.776 *StudyWeek + 0.133*TreatmentGroup*StudyWeek.

The full model including this interaction term was: 25.351 −1.149*TreatmentGroup – 1.170*StudyWeek + 0.497*TreatmentGroup*StudyWeek.

The full model including this interaction term was: 11.030+2.276*TreatmentGroup−0.405*StudyWeek−0.246*TreatmentGroup*StudyWeek.

“SD” = standard deviation.

T test of difference in mean score at week 8 minus mean score at baseline. (For the observed case analysis, using the value for each participant at study completion if prior to week 8).

Effect Size d IGPP (Independent-Group Pre-Post) calculated per formula and recommendations provided by Reference 19: d = Mean Change (Memantine Group) /S.D.Memantine Group at Baseline−Mean Change (Placebo Group)/S.D.Placebo Group at Baseline. (Standard Deviations at Baseline are provided in Table 1). A positive effect size indicates a lower final mean score for placebo recipients than memantine recipients.

LOCF = Last observation carried forward analysis.

A post hoc exploratory subanalysis was also performed examining change in mean MADRS score (LOCF) observed in participants with the greatest initial depression severity (baseline MADRS ≥ the median baseline score): − 8.56 (95% confidence interval (CI) −13.28, −3.28) (9 memantine recipients), −11.00 (95% CI −23.65, 1.65) (7 placebo recipients).

Observed case = all rating scale observations used, but observations not carried forward (no imputation).

Baseline observation for one participant receiving placebo is missing (baseline mean determined without this participant) but Week 8 observation for this participant included in the analysis.

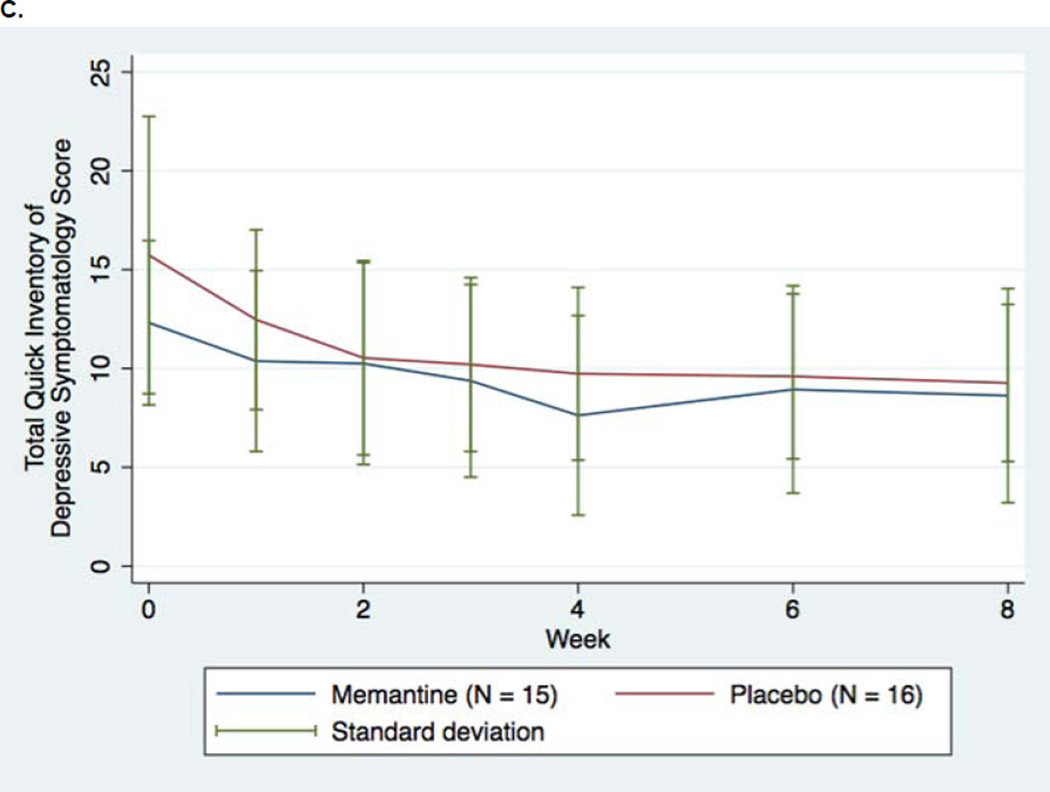

FIGURE 2.

Changes in Depression Rating Scale Scores for Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Assigned to Memantine or Placebo Augmentation of Antidepressant Treatment (LOCF). A. Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scales (LOCF, primary outcome) B. Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scales (No imputation [“Observed Case”]) C. Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, Self-Rated

Mean MADRS score change (LOCF) for memantine recipients at week 8 was −7.13 +/− 6.61 (standard deviation); mean MADRS change for placebo recipients was −7.25 +/−11.14 (Table 2B). A Cohen’s d effect size for change in MADRS score from baseline through week 8 of 0.19 (favoring placebo) was observed. A larger, although nonsignificant, change in MADRS score from baseline through study completion favoring placebo was observed for the nonimputed, observed case mixed model (7.13+/−6.11 [memantine] versus 10.75+/− 10.46 [placebo]), resulting in a medium-sized effect size (d=0.69) favoring placebo. Both these effect size estimates are larger than what simple comparisons of the change scores between memantine and placebo might suggest, since score changes for each treatment group being compared to that group’s baseline standard deviation19 (which is a narrow +/− 6.92 points for placebo recipients). A comparison of effect sizes based on final MADRS scores for the memantine and placebo groups would produce much more modest effect sizes favoring placebo (d=0.02 [LOCF] and d=0.25 [observed case]). A post hoc secondary analysis comparing baseline to week 8 MADRS change for patients with the greatest baseline depression severity also did not reveal differences favoring memantine (Table 2B, Footnote e).

Similarly, no statistically significant differences were observed for the other secondary depression outcome (QIDS-SR) in repeated measure analysis (beta=−0.246, p=0.22) or at week 8 comparison (accompanied by a neglible effect size of −0.04). However, the QIDS-SR results do directionally favor memantine, and the difference in score change at week 8 shows a smaller, although still nonsignificant, p value than the MADRS outcomes (p=0.14). Nevertheless, the changes in depression rating scales over time (Figure 2A–C) suggest little evidence of efficacy for memantine compared to placebo as measured by either QIDS-SR or MADRS.

The secondary endpoints of response and remission based on MADRS score also yielded non-significant results: 13.3% (n=2) of participants receiving memantine had a response or remission by 8 weeks, versus 18.8% (n=3) of participants receiving placebo (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00). These results produce a nonsignificant number-needed-to-treat favoring placebo of approximately 18.

No significant differences were observed using the Ham-A anxiety scale, the suicidal or delusional thinking scales, or in any reported adverse effects (Table 3). Two serious adverse effects were reported that required hospitalization, both involving worsening of pre-existing respiratory problems judged probably unrelated to study medication (one participant received memantine and one participant received placebo).

TABLE 3.

Adverse Events in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Assigned Memantine or Placebo Augmentation of Antidepressant Treatment

| Memantine Augmentation | Placebo Augmentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | N, (%) | N, (%) |

P Valuea |

| PSYCHIATRIC | |||

| Anxiety | 3 (20.00) | 3 (18.75) | 1.000 |

| Irritability | 2 (13.33) | 2 (12.50) | 1.000 |

| Emotional Lability | 2 (13.33) | 2 (12.50) | 1.000 |

| Hypomania/Mania | 0 (0.00) | 2 (12.50) | 0.484 |

| Internal sensation of speed or rapid thoughts | 0 (0.00) | 3 (18.75) | 0.226 |

| Restlessness | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Passive SI | 2 (13.33) | 1 (6.25) | 0.600 |

| Active SI | 1 (66.7) | 2 (12.50) | 1.000 |

| Unusual belief/perceptionb | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| GENERAL | |||

| Headache | 5 (33.33) | 5 (31.25) | 1.000 |

| Back pain | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Generalized aches | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Diaphoresis | 1 (6.7) | 3 (18.75) | 0.600 |

| Chills | 0 (0.00) | 2 (12.50) | 0.484 |

| Clammy hands | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Feeling flushed/hot | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Increased Menstrual Pain | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Dizziness | 1 (6.67) | 5 (31.25) | 0.172 |

| Lightheadedness | 3 (20.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.101 |

| Balance or gait problems | 1 (6.67) | 3 (18.75) | 0.600 |

| Leg weakness | 1 (6.67) | 2 (12.50) | 1.000 |

| Falls | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| DERMATOLOGICAL | |||

| Rash | 0 (0.00) | 2 (12.50) | 0.484 |

| Puritus | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Worsened Acne | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Skin lesion | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| SLEEP AND ENERGY | |||

| Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep | 4 (26.67) | 5 (31.25) | 1.000 |

| Worsened sleep apnea | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Nightmares | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Sleepwalking | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| Sedation/Somnolence | 4 (26.67) | 4 (25.00) | 1.000 |

| Fatigue | 4 (26.67) | 6 (37.50) | 0.704 |

| COGNITIVE | |||

| Confusion/Decreased mental clarity | 2 (13.33) | 2 (12.50) | 1.000 |

| Mild dissociative symptoms | 2 (13.33) | 1 (6.25) | 0.600 |

| GASTROINTESTINAL | |||

| Nausea | 1 (6.67) | 6 (37.50) | 0.083 |

| Vomiting | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Taste perversion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Perceived Weight Gain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Perceived Weight Loss | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Carbohydrate craving | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.50) | 0.484 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Dry mouth | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| Constipation | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| CARDIOPULMONARY/THORACIC | |||

| Heart Palpitations | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Difficulty Breathing | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Chest pain | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| NEUROLOGIC | |||

| Parasthesia/Neuropathy Exacerbation | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Facial Twitching | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| Dyskinesia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| SENSORY | |||

| Tinnitus | 1 (6.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0.484 |

| Eye Photosensitivity | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| INFECTIOUS/POTENTIALLY INFECTIOUS | |||

| URI (Upper Respiratory) Symptoms | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.50) | 0.484 |

| Sore throat | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Conjunctival swelling | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Head Pressure/Ear Pressure | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Ear Pain/Jaw Pain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.25) | 1.000 |

Fisher’s exact test.

One participant receiving memantine endorsed a vague fear of imminent harm repeatedly during an everyday event but maintained it had existed for months prior to study entry, although it was not detected on the baseline screening of unusual thoughts.

The integrity of blinding was assessed through “guess tests” administered to participants, research coordinators, and study psychiatrists. No group was able to accurately distinguish memantine from placebo (p>0.05 for all results), with the highest proportion of correct guesses only 57.1% (observed among participants receiving memantine).

DISCUSSION

In this placebo-controlled, flexibly-dosed randomized trial in which all participants assigned memantine received the highest approved dosage (20 mg/day), no statistically significant differences were observed between memantine and placebo as augmentation agents in incomplete or nonresponders to conventional antidepressants. The primary outcome, repeatedly-measured change in MADRS score, was both statistically nonsignificant (p=0.74) (although limited sample size restricts power), and a minimal effect size was observed at week 8 (Cohen’s d=0.19), favoring placebo. The MADRS observed case repeated measures analysis was also nonsignificant (p= 0.21), with a larger week 8 effect size favoring placebo. Response and remission rates were also nonsignificant and slightly favored placebo.

In contrast, change in self-rated depression (QID-SR) were also nonsignificant but favored memantine in both repeated measures analysis and at week 8. However, interpretation of the change in QIDS-SR score likely is complicated by the fact that this outcome had the greatest (albeit nonsignificant) baseline imbalance of any rating scale (3.4 points). This difference may have facilitated the observation of greater changes in QID-SR in the memantine group. The memantine groups’ baseline scores were also more variable (standard deviation of 7.01 versus 4.16), resulting in an effect size observed at week 8 that was negligible (d=−0.04) despite the more sizable changes in QIDS-SR score observed for the memantine group.

Given the early termination of our trial, we derived post hoc power estimates for our final sample size, taking into account our repeated measures design (which boosts power).20 We estimate that our trial likely had the ability to discriminate an approximate effect size for the primary outcome in the range of Cohen’s d = 0.53. This is less power than would be desired. However, while both this study and the previous placebo-controlled trial of memantine monotherapy in major depressive disorder6 were limited by almost identically small sample size, it may be notable that both trials observed multiple outcomes that numerically favored placebo.

With a sample size falling between a typical Phase I and Phase II trial, our investigation might be viewed as consistent with the recently-proposed “quick win, fast fail” approach to drug evaluation.21 This approach emphasizes the value of small studies for boosting efficiency in drug development through a focus on detecting substantial effect sizes, not statistical significance, although Type 2 errors (i.e., failure to identify valuable interventions) are possible.21 For this trial, the observations that the observed drug versus placebo difference was minimal, few participants dropped out, and maximum titration of possible dose was achieved for all memantine-receiving participants would all likely lessen the chances of Type 2 error.

Limitations of our trial design beyond sample size included the fact that participants could be receiving any one of a substantial number of existing antidepressants, although specific antidepressants appeared to be generally balanced between treatment groups (Table 1). We also did not limit the amount of response participants may have already had to their antidepressant (as long as baseline HAM-D 17 was ≥16), nor imposed limits on the length of time participants could have received their current antidepressant (beyond a minimum of 25 days). This 25-day period was intended to replicate the earliest point (approximately 30 days) at which at patient-provider discussions might occur about next steps in pharmacotherapy for patients experiencing an incomplete or nonresponse to antidepressants. A longer preceding treatment requirement could have yielded lower placebo response rates and reduced the chance some participants were still experiencing change in depression produced by their concomitant antidepressant; however, these concerns are considerably mitigated by the observation that, for the 77% of participants for whom information on duration of current antidepressant treatment was available, only 3 of 24 (12.5%) had received antidepressants for 3 months or less prior to trial enrollment (16.7% of memantine and 8.3% of placebo recipients [Table 1]).

Like most,6, 22, 23 but not all,24 prior trials of memantine for depression, our dosing did not exceed the maximum dose approved for human use (20 mg/day). A small pilot study (n=8),24 in which 37.5% of the participants received doses of memantine of 30–40 mg/day, reported a much higher rate of treatment responders (62.5%) than either our trial (13.3%) or the placebo-controlled monotherapy trial.6 However, this 8-subject pilot study’s open-label design and requirement of prior positive response to antidepressant treatment may have considerably boosted responses independent of any effects from higher dosage. Furthermore, the decision whether to evaluate higher-than-currently-approved dosages of memantine for major depressive disorder may need to consider emerging toxicological literature reporting NMDA antagonist-associated neurotoxicity in some animal models of the developing brain. This literature which has prompted FDA hearings to discuss the relevance to human anesthetic use of NMDA antagonists, especially in children.25–27 Two major reservations concerning the relevance of these animal safety studies have been raised, the first involving the need to employ excessive doses compared to human use, and the second concerning the use of “unrealistically long” (i.e., multi-day) exposures.25 While the first reservation concerning dosing would still apply to potential psychiatric use (and it may be additionally reassuring that NMDA-antagonists are being investigated in adults, not children), the second reservation (concerning duration of exposure) potentially would not apply to likely psychiatric use of oral NMDA-antagonists.

Strengths of our study include the generally good balance achieved on measured participant characteristics despite small sample size, the generally low dropout rate, the success of blinding, the success in titrating all memantine recipients to maximum dose, and the use of a repeated measures design.

To our knowledge, this trial is the only randomized placebo-controlled trial of memantine as an augmentation agent added to antidepressant treatment. Two other placebo-controlled trials have reported a lack of efficacy for memantine as an augmentation agent in other psychiatric conditions (bipolar depression22 and schizophrenia28).. A placebo-controlled trial of memantine as a prophylactic monotherapy for depressive symptoms among elderly patients requiring physical rehabilitation29 also failed to demonstrate efficacy.

In conclusion, this randomized trial did not detect statistically significant differences between augmentation of conventional antidepressants with memantine and placebo and also did not detect substantial effect sizes favoring memantine.. While this study’s small sample size is a limitation, its findings suggest that memantine lacks substantial efficacy as an augmentation treatment for major depressive disorder.

CLINICAL POINTS.

This placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial, although small, did not find efficacy for the oral NMDA-antagonist memantine as an augmentation treatment in major depressive disorder.

This study joins a placebo-controlled monotherapy trial and several other randomized controlled trials in suggesting a lack of efficacy for depression symptoms

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by an investigator-initiated grant to Dr. Smith from Forest Research Institute, an affiliate of Forest Laboratories, the manufacturer of memantine, with Drs. Patel and Deligiannidis serving as Principal Investigator for parts of the trial. Forest Laboratories also provided study drug and placebo. Forest Labs had an opportunity to review the final manuscript but otherwise had no role in the data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation. The sponsor had no role in the study design or conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation or approval of the manuscript. Forest Research Institute had an opportunity to review the final manuscript, but no modifications were requested or made.

Dr. Smith currently receives research support from a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award for work separate from this study. He also received funding from the study sponsor, Forest Research Institute, for a separate study concerning antidepressants and blood pressure, but not in the last 12 months. Dr. Deligiannidis has received investigator-initiated research support from Forest Research Institute for completion of this study and grant support from NIH UL1 TR000161. She received research support from UMass Medical School as well. Dr. Jayendra Patel has served on the Speaker’s Bureau of Sunovian and Merck. Dr. Rothschild has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Cyberonics, Takeda, and St. Jude Medical, has served as a consultant to Allergan, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Sunovian, has received royalties for the Rothschild Scale for Antidepressant Tachyphylaxis (RSAT)™, and has received royalties from American Psychiatric Press, Inc. for Psychoneuroendocrinology: The Scientific Basis of Clinical Practice (2003), Clinical Manual for Diagnosis and Treatment of Psychotic Depression (2009), The Evidenced-Based Guide to Antipsychotic Medications (2010), and The Evidenced-Based Guide to Antidepressant Medications (2011).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Ms. Landolin and Ms. Ulbricht report no financial relationships with commercial interests or other conflicts to disclose.

Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov registration number, NCT00344682.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machado-Vieira R, Ibrahim L, Henter ID, et al. Novel glutamatergic agents for major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;100(4):678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathew SJ, Murrough JW, aan het Rot M, et al. Riluzole for relapse prevention following intravenous ketamine in treatment-resistant depression: a pilot randomized, placebo-controlled continuation trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(1):71–82. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanacora G, Zarate CA, Krystal JH, et al. Targeting the glutamatergic system to develop novel, improved therapeutics for mood disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(5):426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrd2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Quiroz JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):153–155. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogoz Z, Skuza G, Kusmider M, et al. Synergistic effect of imipramine and amantadine in the forced swimming test in rats. Behavioral and pharmacokinetic studies. Pol J Pharmacol. 2004;56(2):179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. text revision ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams JB, Kobak KA, Bech P, et al. The GRID-HAMD: standardization of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(3):120–129. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f948f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, Kartachov A, et al. A computer algorithm for calculating the adequacy of antidepressant treatment in unipolar and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(7):825–833. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47(2):343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitzer R, Endicott J. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Dept, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vickers AJ. How many repeated measures in repeated measures designs? Statistical issues for comparative trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(3):203–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anand A, Gunn AD, Barkay G, et al. Early antidepressant effect of memantine during augmentation of lamotrigine inadequate response in bipolar depression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(1):64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhonen LH, Lonnqvist J, Juva K, et al. Double-blind, randomized comparison of memantine and escitalopram for the treatment of major depressive disorder comorbid with alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(3):392–399. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson JM, Shingleton RN. An open-label, flexible-dose study of memantine in major depressive disorder. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30(3):136–144. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3180314ae7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green SM, Cote CJ. Ketamine and neurotoxicity: clinical perspectives and implications for emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(2):181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA Advisory Committee Background Document: Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee (ALSDAC) meeting minutes. 2007 Mar 29; http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/transcripts/2007-4285t1.pdf [June 12, 2012]

- 27.FDA Advisory Committee Background Document to the Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee (ALSDAC) 2011 Mar 10; http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM245769.pdf [June 28, 2012]

- 28.Lieberman JA, Papadakis K, Csernansky J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of memantine as adjunctive treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 Apr;34(5):1322–1329. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenze EJ, Skidmore ER, Begley AE, et al. Memantine for late-life depression and apathy after a disabling medical event: a 12-week, double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(9):974–980. doi: 10.1002/gps.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]