Significance

Telomeres protect DNA ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes from degradation and fusion through the recruitment of telomerase. We previously found that SUMOylation negatively regulates telomere extension; however, how SUMOylation limits telomere extension has remained unknown until now. Here we provide major mechanistic insights into how the SUMOylation pathway collaborates with shelterin and Stn1-Ten1 complexes to regulate telomere length. We establish that SUMOylation of the shelterin subunit TPP1 homolog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Tpz1) prevents telomerase accumulation at telomeres by promoting recruitment of Stn1-Ten1 to telomeres in S-phase. Thus, our findings establish that Tpz1 not only contributes to telomerase recruitment via its interaction with Ccq1-Est1, but also contributes to the negative regulation of telomerase via its SUMOylation-mediated interaction with Stn1-Ten1.

Keywords: CST complex, DNA replication, S-phase, cell cycle

Abstract

Telomeres protect DNA ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes from degradation and fusion, and ensure complete replication of the terminal DNA through recruitment of telomerase. The regulation of telomerase is a critical area of telomere research and includes cis regulation by the shelterin complex in mammals and fission yeast. We have identified a key component of this regulatory pathway as the SUMOylation [the covalent attachment of a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) to target proteins] of a shelterin subunit in fission yeast. SUMOylation is known to be involved in the negative regulation of telomere extension by telomerase; however, how SUMOylation limits the action of telomerase was unknown until now. We show that SUMOylation of the shelterin subunit TPP1 homolog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Tpz1) on lysine 242 is important for telomere length homeostasis. Furthermore, we establish that Tpz1 SUMOylation prevents telomerase accumulation at telomeres by promoting recruitment of Stn1-Ten1 to telomeres. Our findings provide major mechanistic insights into how the SUMOylation pathway collaborates with shelterin and Stn1-Ten1 complexes to regulate telomere length.

Telomeres protect DNA ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes from degradation and fusion, and ensure replication of the terminal DNA (1, 2). In most eukaryotes, telomere length is maintained predominantly by telomerase, a specialized reverse transcriptase that adds telomeric DNA to the 3′ ends of chromosomes. In addition, a DNA homologous recombination (HR)-dependent mechanism, known as the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) pathway, may contribute to telomere maintenance (3). Given the significant contribution of dysfunctional telomeres to genome instability, cancer development, and aging (4), understanding how telomere maintenance and the cellular response to telomere dysfunction is important. Maintenance of stable telomere length requires a balance of positive and negative regulators of telomerase. The molecular details of such regulation are not completely understood, however, and further investigation of how telomeres ensure genomic integrity is needed.

Telomere regulation is largely mediated by the shelterin complex specifically bound to telomeric repeats (2). In mammalian cells, the shelterin complex (composed of TRF1, TRF2, RAP1, TIN2, TPP1, and POT1) plays critical roles in (i) regulating telomerase recruitment, (ii) preventing full-scale activation of DNA damage checkpoint responses by checkpoint kinases ATM and ATR, (iii) preventing DNA resection, and (iv) preventing telomere rearrangement and fusion by HR, classical nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ), or alternative NHEJ (2, 5, 6).

Fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe serves as an attractive model system for studying telomere regulation, because it uses a complex that closely resembles the mammalian shelterin (7). Fission yeast shelterin is composed of Taz1 (an ortholog of TRF1 and TRF2), Rap1, Poz1 (a possible analog of TIN2), TPP1 homolog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Tpz1) (an ortholog of TPP1), Pot1, and Ccq1. Whereas Taz1 binds to double-stranded G-rich telomeric repeats, Pot1 binds to 3′ single-stranded overhang telomeric DNA, known as G-tails (8, 9). Rap1, Poz1, and Tpz1 act as a molecular bridge connecting Taz1 and Pot1 through protein–protein interactions (7), and Ccq1 contributes to telomerase recruitment via Rad3ATR/Tel1ATM-dependent interaction with the telomerase regulatory subunit Est1 (10).

Because of its direct interaction with Pot1 via its N terminus and with Poz1 and Ccq1 via its C terminus (Fig. 1A) (7), Tpz1 functions as an important node in the protein–protein interaction network at telomeres. Although the circuitry of interactions among shelterin components has been well documented and studied, how core shelterin subunits such as Tpz1 help coordinate the cross-talk between telomere-specific signaling pathways and other cellular networks remains unclear.

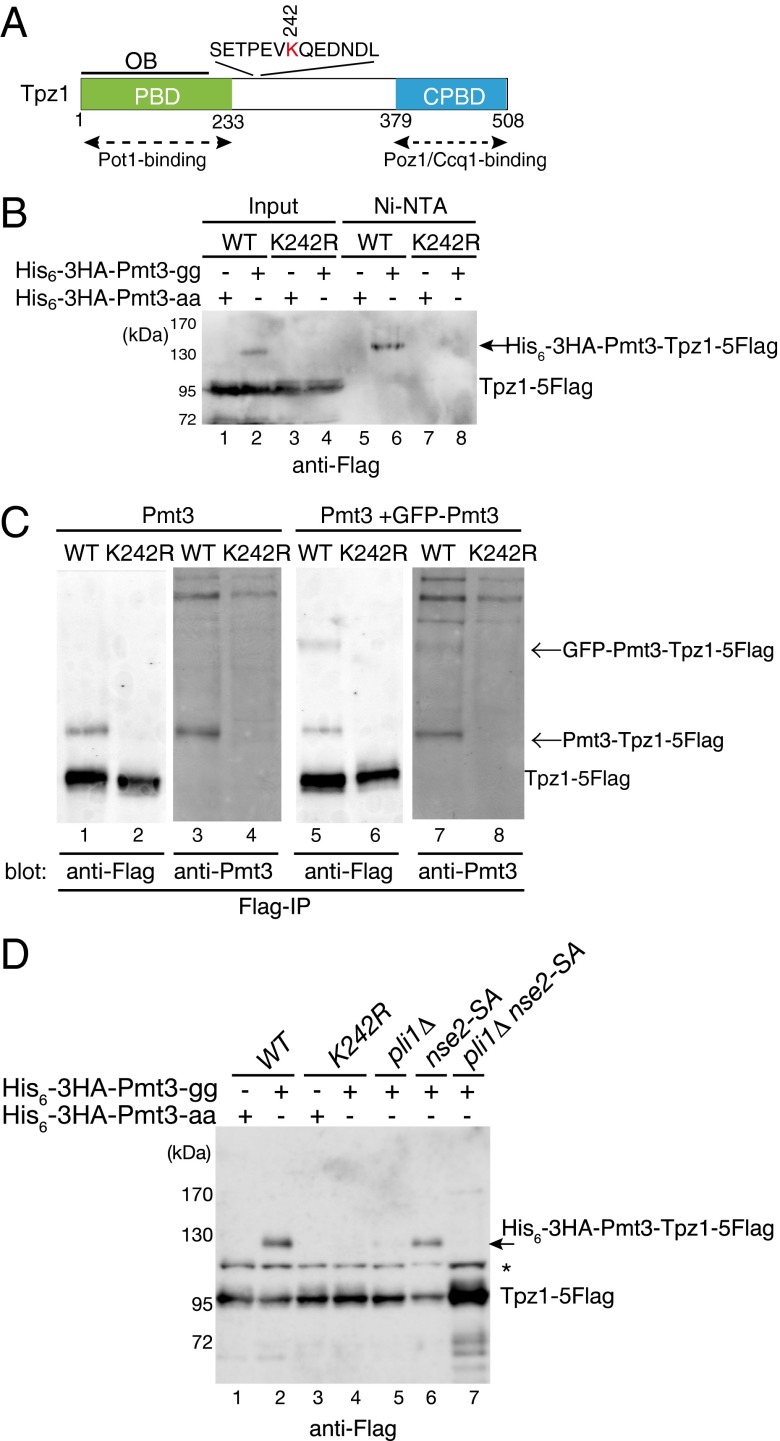

Fig. 1.

Tpz1 is SUMOylated at K242 in a manner dependent on the SUMO E3 ligase Pli1. (A) Schematic representation of Tpz1 functional domains. Pot1-, Poz1-, and Ccq1-interacting domains, as well as a predicted OB fold domain (OBD), are shown. The SUMOylation consensus site and position of the SUMOylated lysine (K242) are also depicted. CPBD, Ccq1/Poz1-binding domain; PBD, Pot1-binding domain. (B) Tpz1 is SUMOylated on K242. His6-3HA-tagged Pmt3-aa or His6-3HA-tagged Pmt3-gg was ectopically expressed from a pREP1-derived vector in tpz1-5Flag (WT) or tpz1-K242R-5Flag (K242R) cells and then purified with Ni-NTA under denatured conditions. Copurifying Tpz1 was detected by anti-Flag Western blot analysis. A band corresponding to SUMOylated Tpz1 is indicated by an arrow. (C) Tpz1 SUMOylation can be detected in cells expressing endogenous levels of Tpz1 and Pmt3. Tpz1-5Flag (WT) and Tpz1-K242R-5Flag (K242R) were immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody from cells expressing endogenous WT Pmt3 only or coexpressing WT and GFP-tagged Pmt3, and detected by Western blot analysis using anti-Flag or anti-Pmt3 antibodies. (D) Tpz1 is SUMOylated primarily by SUMO E3 ligase Pli1. His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3-aa or His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3-gg was ectopically expressed from pREP1-derived vectors in fission yeast cells with indicated genotypes, and Tpz1-5Flag protein was detected by Western blot analysis. His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3-modified Tpz1-5Flag is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band.

Another evolutionarily conserved complex, known as CST (Cdc13-Stn1-Ten1 in budding yeast and CTC1-STN1-TEN1 in vertebrates) is also required for telomere stability (11, 12). Although a CTC1/Cdc13 ortholog has not yet been identified, the Stn1-Ten1 complex is known to be essential for telomere stability in fission yeast (13). The coexistence of shelterin and CST at telomeres in most eukaryotes suggests a division of roles among complexes responsible for end protection and telomere replication (12); however, how shelterin and CST cooperate in telomere function remains to be determined.

It is becoming increasingly clear that dynamic protein posttranslational modifications play important roles in regulating telomere length, possibly by modifying some of the telomerase regulators. SUMOylation, the covalent attachment of a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) to target proteins, plays important roles in a wide variety of cellular functions, including DNA repair, cell cycle progression, and chromatin dynamics (14). Like the modification with ubiquitin (ubiquitylation) and other ubiquitin-like modifiers, SUMOylation is achieved with a distinct but evolutionarily conserved enzymatic cascade consisting of E1-activating, E2-conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes (15–17). Factors involved in SUMOylation regulate recombination-based telomere maintenance in mammals and budding yeast (18–20), and SUMOylation of Cdc13 promotes Cdc13–Stn1 interaction to restrain telomerase-dependent telomere elongation in budding yeast (21). In fission yeast, mutations of SUMO (Pmt3) or SUMO E3 ligase (Pli1) lead to long telomeres in a telomerase-dependent manner (22, 23). The underlying molecular mechanism of SUMO-dependent telomere regulation remains unknown, however.

In this study, we identified Tpz1 as a target of SUMOylation, and determined that Tpz1 SUMOylation prevents telomerase accumulation at telomeres by promoting recruitment of Stn1-Ten1 to telomeres. Our findings thus provide major mechanistic insights into the role of SUMOylation in fission yeast telomere length homeostasis.

Results

Shelterin Subunit Tpz1 Is SUMOylated at K242 by SUMO E3 Ligase Pli1.

To identify proteins involved in telomere maintenance that might be SUMOylated, we epitope-tagged various known telomere proteins at their endogenous loci in strains that overexpressed either His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3-aa (nonconjugatable form) or His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3-gg (conjugatable form). Protein extracts were then produced under denaturing conditions to preserve SUMOylated forms, and His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3 was purified from cell extracts with Ni-NTA resin under denaturing conditions. SUMOylated epitope-tagged proteins were subsequently detected by Western blot analysis using epitope-specific antibodies. Based on these analyses, we identified Tpz1 as a potential SUMO substrate (Fig. 1B).

Sequence analysis of Tpz1 revealed an evolutionarily conserved consensus SUMOylation site, Ψ-K-x-E/D (Ψ, bulky hydrophobic residue; x, any amino acids) in the region between the PBD (Pot1-binding domain) and CPBD (Ccq1/Poz1-binding domain) of Tpz1 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A). Mutation of this putative SUMO site (lysine 242) to arginine (K242R) did not affect Tpz1 protein stability (Fig. S1B), but did cause a loss of detectable Tpz1-Flag from the Ni-NTA resin-purified fraction (Fig. 1B, lane 8), suggesting that Tpz1-K242 is SUMOylated. The tpz1-K242R allele thus provides a useful genetic tool for assessing the role of Tpz1 SUMOylation in telomere metabolism.

To ensure that Tpz1 SUMOylation was not caused by ectopic overexpression of His6-3HA–tagged Pmt3, we repeated our analysis using fission yeast cells expressing WT Pmt3 alone or coexpressing both WT and GFP-tagged Pmt3 under control of the pmt3 promoter (22). On anti-Flag immunoprecipitation (IP), we detected an extra band above Tpz1 on anti-Flag Western blots of the exact same size as a major band detected by the anti-Pmt3 antibody (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 3). This extra band was not seen in the tpz1-K242R mutant strain, and was increased in size when GFP-Pmt3 was coexpressed (Fig. 1C).

We also found that Tpz1 SUMOylation was greatly reduced in pli1Δ cells and completely eliminated in pli1Δ nse2-SA cells, which carry a deletion and a catalytically inactive mutation of the SUMO E3 ligases Pli1 and Nse2, respectively (Fig. 1D) (24). Thus, we conclude that Pli1 is primarily responsible for Tpz1 SUMOylation, with Nse2 possibly playing a minor role.

Tpz1-K242 SUMOylation Limits Telomerase-Dependent Telomere Elongation.

Mutations of SUMO or SUMO E3 ligases in fission yeast lead to longer telomeres in a telomerase-dependent manner (23). To determine whether SUMOylation of Tpz1 has a role in regulating telomere length, we examined how the tpz1-K242R mutation affects telomere length. Southern blot analysis revealed that tpz1-K242R cells carry highly elongated telomeres, suggesting a critical role for Tpz1-K242 SUMOylation in the negative regulation of telomere length (Fig. 2B). Unlike tpz1Δ cells, which showed severe growth defects and rampant telomere loss and fusion (7), tpz1-K242R cells grew normally and demonstrated no telomere loss or fusion. Furthermore, co-IP analyses showed that Ccq1–Tpz1, Pot1–Tpz1, and Poz1–Tpz1 interactions are not affected by the tpz1-K242R mutation (Fig. S2). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays also indicated that tpz1-K242R mutation does not affect the association of Tpz1, Poz1, Ccq1, or Pot1 with telomeres (Fig. S3 A and B). Taken together, these findings identify tpz1-K242R as a separation-of-function mutation that is specifically defective in limiting telomere elongation without affecting the integrity of the shelterin complex. Furthermore, telomere length in tpz1-K242R pmt3Δ cells was similar to that of tpz1-K242R or pmt3Δ cells (Fig. 2 B and C), suggesting that the telomere elongation seen in pmt3Δ cells can be attributed primarily to the loss of Tpz1-K242 SUMOylation.

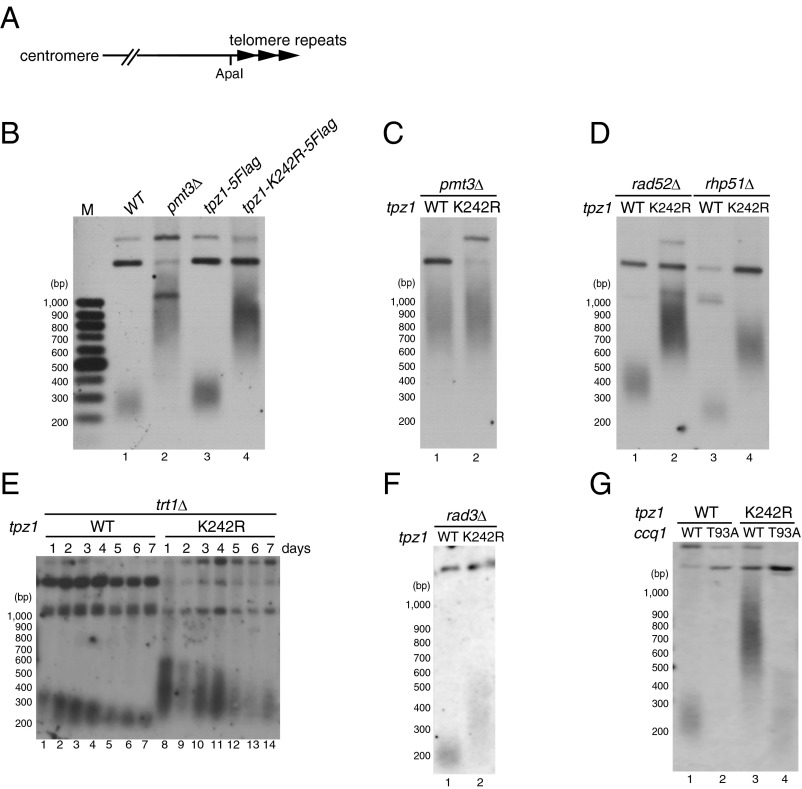

Fig. 2.

Tpz1 SUMOylation is required for telomerase-dependent telomere length homeostasis. (A) A schematic representation of fission telomeres. ApaI-digested genomic DNA was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with a telomere DNA probe. (B–G) Telomere length analyses of various fission yeast strains with indicated genotypes. In all panels except E, haploid cells with indicated genotypes were restreaked extensively to ensure that telomeres reached terminal length. For E, heterozygous diploid strains (trt1+/trt1Δ tpz1+/tpz1-5Flag and trt1+/trt1Δ tpz1+/tpz1-K242R-5Flag) were sporulated, and haploid cells with desired genotypes were picked and grown in yeast extract with supplements (YES) cultures at 30 °C for 2 d. Cultures were then used to inoculate fresh YES cultures, and remaining cells were collected for genomic DNA preparation (day 1). Subsequently, cultures were collected every 24 h on days 2–7 (Materials and Methods).

Because telomere elongation in tpz1-K242R cells may result from improper regulation of telomerase or telomere recombination, we investigated possible roles of the HR repair proteins Rad52 and Rhp51 (an ortholog of Rad51) (25) in telomere elongation, and found that telomeres were highly elongated in tpz1-K242R rad52Δ and tpz1-K242R rhp51Δ cells, to the same extent as in tpz1-K242R cells (Fig. 2D). In contrast, deletion of the telomerase catalytic subunit Trt1TERT caused progressive shortening of telomeres in tpz1-K242R trt1Δ cells (Fig. 2E), indicating that the telomere elongation phenotype in tpz1-K242R cells is dependent on telomerase.

In fission yeast, Rad3ATR/ Tel1ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Ccq1 on threonine 93 (T93) promotes recruitment of telomerase to telomeres (10, 26). We found that rad3Δ (Fig. 2F) and ccq1-T93A (Fig. 2G) significantly reduced telomere elongation caused by tpz1-K242R, suggesting that Rad3ATR/Tel1ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Ccq1-T93 is required for telomere elongation in tpz1-K242R cells. Furthermore, ChIP assays demonstrated significantly increased Trt1 binding to telomeres in tpz1-K242R cells (Fig. 3A), suggesting that Tpz1 SUMOylation prevents uncontrolled telomere elongation by negatively regulating the association of telomerase with telomeres.

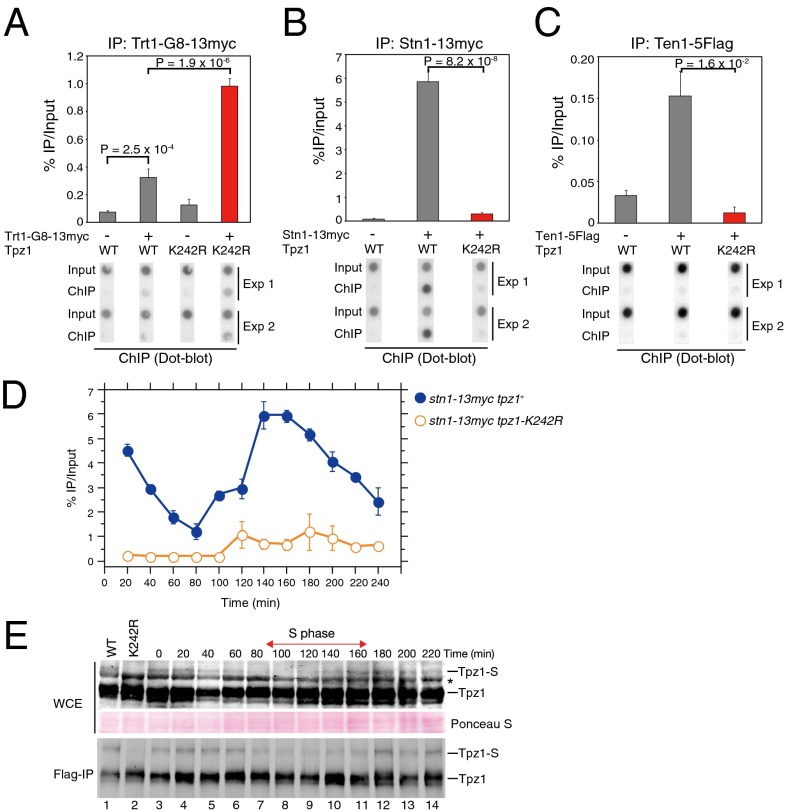

Fig. 3.

Late S/G2-phase SUMOylation of Tpz1 promotes efficient recruitment of Stn1-Ten1 to telomeres. (A–C) Telomere association of Trt1TERT (A), Stn1 (B), or Ten1 (C), monitored with dot blot ChIP assays. ChIP experiments were performed using samples collected from exponentially growing WT tpz1+ or tpz1-K242R (K242R) cells, carrying the indicated epitope-tagged proteins. Error bars indicate the SEM from multiple independent experiments (n ≧ 4). (D) Tpz1 SUMOylation promotes late S/G2 phase accumulation of Stn1 to telomeres. Synchronized cell cultures were obtained using cdc25-22, and cell cycle-regulated Stn1 binding to telomeres was monitored by dot blot ChIP assays. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 4). (E) Tpz1 SUMOylation is reduced in early/mid S phase. Synchronized cell cultures were obtained using cdc25-22, and Tpz1 SUMOylation was monitored by anti-Flag Western blot analysis of either WCE or anti-Flag IP. The SUMOylated Tpz1 band is labeled Tpz1-S. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band.

Late S/G2 Phase SUMOylation of Tpz1 Promotes Stn1-Ten1 Association with Telomeres.

Previous studies found that the human CST complex functions as a terminator of telomerase activity (27). In addition, both human CST and fission yeast Stn1-Ten1 maximally bind to telomeres in late S/G2 phase, when telomerase must dissociate from telomeres before entering mitosis (27, 28). These properties prompted us to examine whether Tpz1 SUMOylation is required for recruitment of the Stn1-Ten1 complex onto telomeres. We found that tpz1-K242R largely abolished association of the Stn1-Ten1 complex with telomeres in ChIP assays (Fig. 3 B and C). Using synchronized cell cultures, we further determined that tpz1-K242R dramatically reduced the late S/G2 phase association of Stn1 with telomeres (Fig. 3D and Fig. S4A), and that Tpz1 SUMOylation was reduced in early/mid S phase but recovered in late S/G2 phase (Fig. 3E and Figs. S4B and S5). Taken together, our results suggest that SUMOylation of Tpz1-K242 is necessary to promote efficient late S/G2 phase association of Stn1-Ten1 with telomeres.

Tpz1-K242 SUMOylation Promotes Tpz1–Stn1 Interaction to Limit Telomere Elongation.

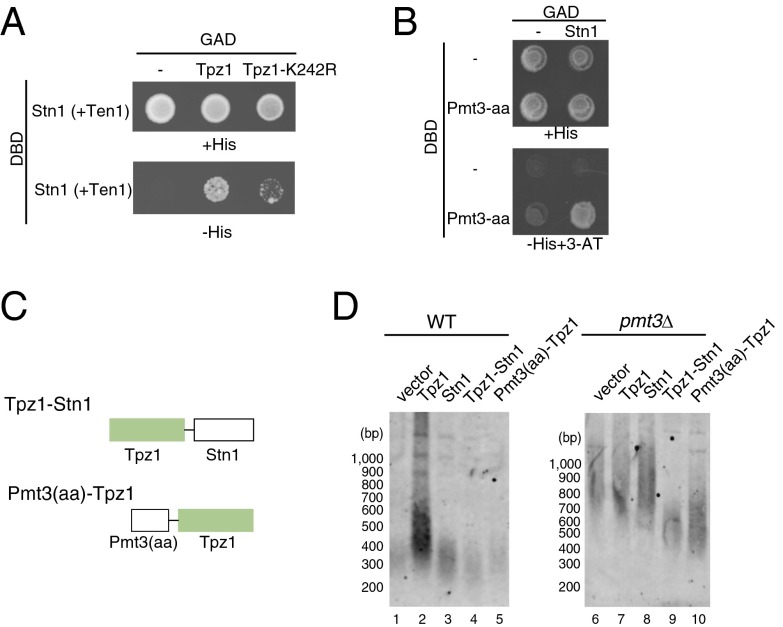

TPP1 and CST appear to directly interact in human cells (27), and we recently reported that fission yeast Tpz1 also interacts with Stn1-Ten1 (29). In a yeast three-hybrid assay, we found that the K242R mutation significantly reduced Tpz1–Stn1-Ten1 interactions (Fig. 4A). In addition, a yeast two-hybrid assay detected interaction between Stn1 and nonconjugatable SUMO (Pmt3-aa) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

SUMOylation-dependent Tpz1–Stn1 interaction promotes telomere shortening. (A) Tpz1-K242R mutation weakens the interaction between Tpz1 and Stn1-Ten1, detected by a yeast three-hybrid assay. The Gal4 activation domain (GAD) was fused to Tpz1, and the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) was fused to Stn1. In addition, cells expressed untagged Ten1. (B) Stn1 interaction with SUMO, detected by a yeast two-hybrid assay between GAD-Stn1 and DBD-Pmt3-aa. (C) Schematic representation of Tpz1-Stn1 and Pmt3-aa-Tpz1 fusion constructs. (D) Ectopic expression of Tpz1-Stn1 or Pmt3-aa-Tpz1 fusion protein causes telomere shortening in pmt3Δ cells. Genomic DNA samples were prepared from WT and pmt3Δ cells carrying indicated plasmids and grown in Edinburgh minimum medium (EMM) supplemented with 5 μM thiamine.

To further analyze the role of Tpz1 SUMOylation from another angle, we generated a Pmt3-aa-Tpz1 construct by fusing SUMO (Pmt3) to the N terminus of Tpz1 (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the idea that fusing SUMO to Tpz1 mimics a constitutively SUMOylated Tpz1 protein, we found that ectopic expression of the Pmt3-aa-Tpz1 fusion protein could suppress telomere elongation in pmt3Δ cells (Fig. 4D). We also generated a Tpz1-Stn1 fusion protein by fusing Tpz1 to the N terminus of Stn1 (Fig. 4C) to mimic a constitutive Tpz1–Stn1 interaction, and found that ectopic expression of the Tpz1-Stn1 fusion protein could suppress telomere elongation in pmt3Δ cells, whereas expression of Tpz1 or Stn1 alone did not affect telomere length in pmt3Δ cells (Fig. 4D). Moreover, expression of Tpz1-Stn1 or Pmt3-aa-Tpz1 fusion protein did not affect telomere length in WT cells (Fig. 4D). These data further support the notion that SUMOylation of Tpz1-K242 prevents telomere elongation by promoting Tpz1–Stn1-Ten1 interaction.

Discussion

Telomeres protect DNA ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes from degradation and fusion, and ensure complete replication of the terminal DNA through recruitment of telomerase. SUMOylation is required for the negative regulation of telomere extension by telomerase in fission yeast (22, 23). How SUMOylation limits telomere extension remains unclear, however. This study provides major mechanistic insights into how the SUMOylation pathway collaborates with shelterin and Stn1-Ten1 to regulate telomere length in fission yeast. Among the numerous cellular targets of SUMOylation, we were able to pinpoint a single SUMOylation site (K242) in Tpz1 to account for telomere elongation. Our findings further suggest that Tpz1 not only promotes telomerase recruitment via its interaction with Ccq1, but also helps terminate telomerase action by SUMOylation-dependent recruitment of the Stn1-Ten1 complex to telomeres (Fig. 5A).

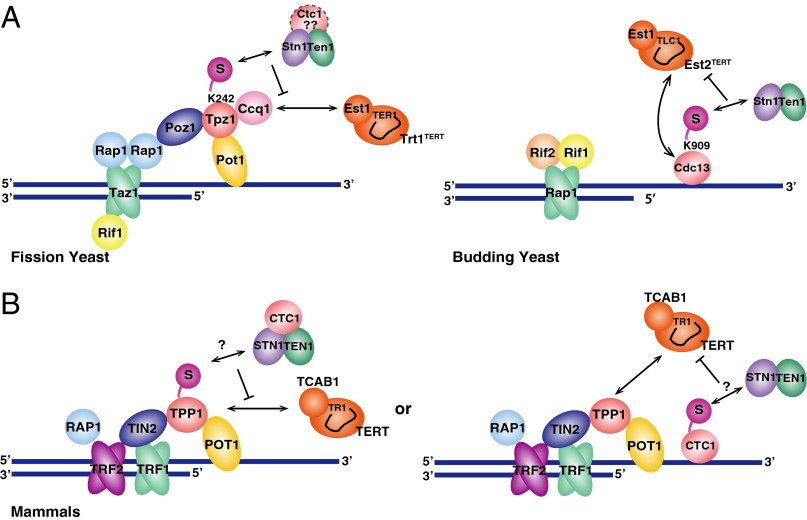

Fig. 5.

Schematic model of telomere regulation by SUMOylation. See text for details. (A) Models in fission and budding yeasts. (B) Predicted models in mammalian cells.

The exact mechanism by which Stn1-Ten1 localization limits telomerase action remains to be established. An attractive possibility is that Stn1-Ten1 limits Ccq1-T93 phosphorylation-dependent accumulation of telomerase to telomeres (10, 26) by stimulating the recruitment of DNA polymerase α (Polα) (30, 31) to reduce single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and subsequently limit Rad3ATR-Rad26ATRIP kinase accumulation at telomeres. Consistently, Polα mutations cause telomere elongation in fission yeast (32), and cells lacking the telomerase inhibitors Poz1 or Rap1 exhibit a long delay in recruitment of Polα (but not the leading strand DNA polymerase ε), leading to increased accumulation of ssDNA, Rad3ATR-Rad26ATRIP, Ccq1-T93 phosphorylation, and telomerase at telomeres (10, 29).

SUMOylation of Cdc13 also has been found to promote Cdc13’s association with Stn1 to restrain telomerase function in budding yeast (Fig. 5A) (21). Furthermore, mutations in Polα also cause telomere elongation in budding yeast (33), and CST interacts with the Polα-primase complex (34, 35). Thus, despite the fact that budding yeast cells lack the shelterin-like complex, SUMOylation-mediated accumulation of Stn1-Ten1 to telomeres may represent a highly conserved regulatory mechanism for controlling telomerase action among budding and fission yeast species (Fig. 5A). Given that fission yeast and mammalian cells use evolutionarily conserved telomere factors, and the interaction between Tpz1/TPP1 and CST is conserved (27, 29, 36), it is likely that SUMOylation-dependent regulation of shelterin and CST is important for telomere regulation in mammalian cells as well. We favor the possibility that SUMOylation modulates the interaction between TPP1 and CST in mammalian cells (Fig. 5B, Left). Alternatively, SUMOylation might modulate the interaction between the CTC1 subunit and the STN1-TEN1 subcomplex, much like in budding yeast (Fig. 5B, Right).

Our present findings highlight the extraordinarily conserved role of SUMOylation in regulating telomerase via modulation of the Stn1-Ten1 association with telomeres. Considering the fact that SUMOylation also plays a conserved role in modulating ALT-based telomere maintenance via regulation of RecQ helicases (18–20), SUMOylation has now emerged as one of the most important posttranslational modifications in telomere maintenance of eukaryotic cells.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains, Plasmids, Growth Conditions, and General Methods.

The fission yeast and budding yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2. Standard growth media (37) were used, supplemented with 100 μg/mL G418 (Sigma-Aldrich), 150 μg/mL Hygromycin B (Roche), or 200 μg/mL nourseothricin (clonNAT; Werner BioAgents) as needed. For strains carrying plasmids expressing proteins from nmt1 or nmt41 promoter, cells were grown to midlog phase overnight at 30 °C in EMM with appropriate growth supplements and 5 μM thiamine (37), washed twice with fresh EMM, and further incubated in EMM without thiamine for 20 h to induce protein expression. His6-3HA-Pmt3–linked proteins were purified under denaturing conditions as described previously (38). For Fig. 2E, trt1Δ haploid cells expressing either Tpz1-5Flag or Tpz1-K242R-5Flag were generated by sporulating heterozygous diploid strains. Cells from colonies with desired genotypes were grown in YES cultures at 30 °C for 2 d. Cultures were then used to inoculate fresh YES cultures and remaining cells collected for genomic DNA preparation (day 1). The subsequent cultures were collected every 24 h on days 2–7.

A fission yeast strain coexpressing WT Pmt3 and GFP-Pmt3 has been described previously (22). In addition, strains carrying pmt3Δ::ura4+ (22), rad3Δ::ura4+ (39), ccq1+::13myc-ura4+ (7), ccq1+::3Flag-kanMX6 (7), ccq1+::3Flag-LEU2 (26), ccq1-T93A::3Flag-LEU2 (26), poz1+::3Flag-LEU2 (7), trt1+::G8-13myc-kanMX6 (40), stn1+::13myc-kanMX6 (28), ten1+::5Flag-TEV-Avitag-kanMX6 (28), pot1+::3Flag-kanMX6 (7), and tpz1+::13myc-kanMX6 (41) have been described previously. The National Bio-Resource Project of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) Japan (yeast.lab.nig.ac.jp/nig/) provided strains with rad52Δ::ura4+ (recently renamed from rad22; FY14150), rhp51Δ::ura4+ (FY14135), spc1Δ::LEU2 (FY14283), trt1Δ::ura4+ (FY14283), and pot1+::HA-ura4 (FY14256).

A PCR-based method (42) was used to generate pli1Δ::natMX6, tpz1+::5Flag-kanMX6, and tpz1+::GFP-hphMX6 strains. The QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) was used to introduce tpz1-K242R mutation into pTN-L1-tpz1 (Table S2) and used as a template for PCR to generate tpz1-K242R::5Flag-kanMX6 and tpz1-K242R::GFP-hphMX6 integration cassettes that were subsequently integrated into the endogenous tpz1+ locus. For the nse2-SA::13myc-hphMX6 stain, pBS-nse2 (Table S2) was mutated with QuikChange to generate a nse2-SA (nse2-C195S-H197A) mutation and used as a template for PCR to generate nse2-SA::13myc-hphMX6 integration cassettes that were subsequently integrated into an endogenous nse2+ locus.

For tpz1-K242R::13myc-kanMX6 strain, pBS-tpz1-13myc-kanMX plasmid was mutated with QuikChange to generate pBS-tpz1-K242R-13myc-kanMX, and a gel-purified BsgI-BglII tpz1-K242R::13myc-kanMX6 fragment was used in transformation to integrate myc-tagged tpz1-K242R into a tpz1+ locus. Subsequently, tpz1-K242R::13myc-kanMX6 strain was transformed with a PCR construct designed to both remove 13myc-tag and replace kanMX6 with hphMX6 to generate a tpz1-K242R::hphMX6 strain.

To create pNmt1-His6-3HA-pmt3 plasmid, a His6 linker sequence was inserted upstream of the 3HA tag of pSLF173L-pmt3 (22). The pmt3 gene was subsequently truncated at the C terminus to generate pNmt1-His6-3HA-pmt3-gg or pNmt1-His6-3HA-pmt3-aa plasmid. The Tpz1-Stn1 fusion plasmid, which expresses 3HA-Tpz1-Stn1 fusion protein under the control of the nmt41 promoter, was generated by cloning a fused tpz1-stn1 cDNA fragment into pSLF273L plasmid. The SUMO-Tpz1 fusion plasmid, which expresses the 3HA-Pmt3-aa-Tpz1 fusion protein under the control of the nmt1 promoter, was generated by cloning a fused pmt3-aa-tpz1 cDNA fragment into pSLF173L plasmid.

Cell Cycle Synchronization.

Temperature-sensitive cdc25-22 cells were incubated at 36 °C for 3–3.5 h to arrest cells at the G2/M boundary, and then shifted to 25 °C to induce synchronous cell cycle reentry. Cell cycle progression was followed by measurement of % septated cells. For strains carrying the cold-sensitive nda3-KM311 mutation, cell were first arrested in M phase at 20 °C for 4 h, and then released synchronously into the cell cycle by the return to a permissive temperature (28 °C).

Yeast Two/Three-Hybrid Assay.

These assays were performed using the Matchmaker System (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For Tpz1–Stn1-Ten1 interaction, MATa (Y2HGold) strains carrying GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) plasmids were mated to MATα (Y187) strains carrying GAL4 activation domain (GAD) plasmids, and the interaction was scored by monitoring growth on SD–HTL (–His) plates. For Pmt3-aa–Stn1 interaction, modified AH109 reporter strains with integrated pAS404 (empty vector control for DBD) or pAS404-pmt3-aa (DBD-Pmt3-aa) was transformed with pGADT7 (empty vector control for GAD) or pGADT7-Stn1, and the interaction was scored by monitoring growth on SD-HTL plates with 2 mM 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole (–His +3-AT).

Southern Blot Analysis for Telomere Length.

Fission yeast genomic DNA was prepared with the Dr. GenTLE (from Yeast) High Recovery System (Takara). DNA was digested with ApaI, separated on a 1.4% agarose gel, and then transferred onto a hybond N+ membrane (GE Healthcare). The 0.3-kb ApaI-EcoRI fragment of pAMP2 (43) was used as a template to generate a probe for telomeric repeat sequences in the AlkPhos Direct Labeling and Detection System (GE Healthcare).

Dot Blot ChIP Assays.

Cells were grown in YES at 32 °C (asynchronous ChIP) or 25 °C (cell cycle ChIP) overnight. Cells were processed for ChIP using anti-Myc 9B11 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling) or anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed by dot blotting with a 32P-labeled telomeric DNA probe, generated using a ApaI-SacI telomere fragment from pTELO plasmid as template DNA and the Prime-It II Random Primer Labeling Kit (Stratagene) as described previously (10, 44). ChIP sample values were normalized to input samples and plotted as percentage of precipitated DNA. ChIP assays based on dot blotting were necessary for cells carrying highly elongated telomeres, because primers used in real-time PCR-based ChIP assays became too distant from chromosome ends.

See SI Materials and Methods for additional information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Fuyuki Ishikawa, Yasushi Hiraoka, Ginger Zakian, Julie Cooper, and Hiroyuki Yamano for providing yeast strains, plasmids, and antibodies, and Drs. Fuyuki Ishikawa, Akira Nabetani, Yusuke Tarumoto, Junko Kanoh, and Jun-ichi Nakayama for discussion and advice. We also thank Tomoaki Arita for technical assistance and Toshiya Fujiwara for graphical assistance. This work was funded by a grant from the Kawanishi Memorial ShinMaywa Education Foundation (to K.T.) and National Institutes of Health Grant GM078253 (to T.M.N.). A.M. was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1401359111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Verdun RE, Karlseder J. Replication and protection of telomeres. Nature. 2007;447(7147):924–931. doi: 10.1038/nature05976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palm W, de Lange T. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:301–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cesare AJ, Reddel RR. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: Models, mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(5):319–330. doi: 10.1038/nrg2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armanios M, Blackburn EH. The telomere syndromes. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(10):693–704. doi: 10.1038/nrg3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sfeir A, de Lange T. Removal of shelterin reveals the telomere end-protection problem. Science. 2012;336(6081):593–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1218498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denchi EL, de Lange T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature. 2007;448(7157):1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyoshi T, Kanoh J, Saito M, Ishikawa F. Fission yeast Pot1-Tpp1 protects telomeres and regulates telomere length. Science. 2008;320(5881):1341–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1154819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann P, Cech TR. Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science. 2001;292(5519):1171–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1060036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper JP, Nimmo ER, Allshire RC, Cech TR. Regulation of telomere length and function by a Myb-domain protein in fission yeast. Nature. 1997;385(6618):744–747. doi: 10.1038/385744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moser BA, Chang YT, Kosti J, Nakamura TM. Tel1ATM and Rad3ATR kinases promote Ccq1–Est1 interaction to maintain telomeres in fission yeast. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(12):1408–1413. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giraud-Panis MJ, Teixeira MT, Geli V, Gilson E. CST meets shelterin to keep telomeres in check. Mol Cell. 2010;39(5):665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price CM, et al. Evolution of CST function in telomere maintenance. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(16):3157–3165. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin V, Du LL, Rozenzhak S, Russell P. Protection of telomeres by a conserved Stn1-Ten1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(35):14038–14043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705497104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peuscher MH, Jacobs JJ. Posttranslational control of telomere maintenance and the telomere damage response. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(8):1524–1534. doi: 10.4161/cc.19847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gareau JR, Lima CD. The SUMO pathway: Emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(12):861–871. doi: 10.1038/nrm3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: A decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(12):947–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson ES. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potts PR, Yu H. The SMC5/6 complex maintains telomere length in ALT cancer cells through SUMOylation of telomere-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(7):581–590. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chavez A, George V, Agrawal V, Johnson FB. Sumoylation and the structural maintenance of chromosomes (Smc) 5/6 complex slow senescence through recombination intermediate resolution. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(16):11922–11930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu CY, Tsai CH, Brill SJ, Teng SC. Sumoylation of the BLM ortholog, Sgs1, promotes telomere-telomere recombination in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(2):488–498. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hang LE, Liu X, Cheung I, Yang Y, Zhao X. SUMOylation regulates telomere length homeostasis by targeting Cdc13. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(8):920–926. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka K, et al. Characterization of a fission yeast SUMO-1 homologue, Pmt3p, required for multiple nuclear events, including the control of telomere length and chromosome segregation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(12):8660–8672. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xhemalce B, et al. Role of SUMO in the dynamics of telomere maintenance in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):893–898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrews EA, et al. Nse2, a component of the Smc5-6 complex, is a SUMO ligase required for the response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(1):185–196. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.185-196.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann AR. Molecular biology of DNA repair in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mutat Res. 1996;363(3):147–161. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(96)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamazaki H, Tarumoto Y, Ishikawa F. Tel1ATM and Rad3ATR phosphorylate the telomere protein Ccq1 to recruit telomerase and elongate telomeres in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2012;26(3):241–246. doi: 10.1101/gad.177873.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen LY, Redon S, Lingner J. The human CST complex is a terminator of telomerase activity. Nature. 2012;488(7412):540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature11269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moser BA, et al. Differential arrival of leading and lagging strand DNA polymerases at fission yeast telomeres. EMBO J. 2009;28(7):810–820. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang YT, Moser BA, Nakamura TM. Fission yeast shelterin regulates DNA polymerases and Rad3ATR kinase to limit telomere extension. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(11):e1003936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3′ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell. 2012;150(1):39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang F, et al. Human CST has independent functions during telomere duplex replication and C-strand fill-in. Cell Rep. 2012;2(5):1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahlen M, Sunnerhagen P, Wang TS. Replication proteins influence the maintenance of telomere length and telomerase protein stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(9):3031–3042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3031-3042.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams-Martin A, Dionne I, Wellinger RJ, Holm C. The function of DNA polymerase α at telomeric G tails is important for telomere homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(3):786–796. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.786-796.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puglisi A, Bianchi A, Lemmens L, Damay P, Shore D. Distinct roles for yeast Stn1 in telomere capping and telomerase inhibition. EMBO J. 2008;27(17):2328–2339. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi H, Zakian VA. The Saccharomyces telomere-binding protein Cdc13p interacts with both the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase α and the telomerase-associated Est1 protein. Genes Dev. 2000;14(14):1777–1788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan M, Qin J, Songyang Z, Liu D. OB fold-containing protein 1 (OBFC1), a human homolog of yeast Stn1, associates with TPP1 and is implicated in telomere length regulation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(39):26725–26731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiozaki K, Russell P. Stress-activated protein kinase pathway in cell cycle control of fission yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1997;283:506–520. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)83040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bentley NJ, et al. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad3 checkpoint gene. EMBO J. 1996;15(23):6641–6651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webb CJ, Zakian VA. Identification and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe TER1 telomerase RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(1):34–42. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moser BA, Subramanian L, Khair L, Chang YT, Nakamura TM. Fission yeast Tel1ATM and Rad3ATR promote telomere protection and telomerase recruitment. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(8):e1000622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krawchuk MD, Wahls WP. High-efficiency gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe using a modular, PCR-based approach with long tracts of flanking homology. Yeast. 1999;15(13):1419–1427. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990930)15:13<1419::AID-YEA466>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuura A, Naito T, Ishikawa F. Genetic control of telomere integrity in Schizosaccharomyces pombe: rad3+ and tel1+ are parts of two regulatory networks independent of the downstream protein kinases chk1+ and cds1+ Genetics. 1999;152(4):1501–1512. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khair L, Subramanian L, Moser BA, Nakamura TM. Roles of heterochromatin and telomere proteins in regulation of fission yeast telomere recombination and telomerase recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(8):5327–5337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.