Abstract

Exploration of non-coding genome has recently uncovered a growing list of formerly unknown regulatory long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) with important functions in stem cell pluripotency, development and homeostasis of several tissues. Although thousands of lncRNAs are expressed in mammalian brain in a highly patterned manner, their roles in brain development have just begun to emerge. Recent data suggest key roles for these molecules in gene regulatory networks controlling neuronal and glial cell differentiation. Analysis of the genomic distribution of genes encoding for lncRNAs indicates a physical association of these regulatory RNAs with transcription factors (TFs) with well-established roles in neural differentiation, suggesting that lncRNAs and TFs may form coherent regulatory networks with important functions in neural stem cells (NSCs). Additionally, many studies show that lncRNAs are involved in the pathophysiology of brain-related diseases/disorders. Here we discuss these observations and investigate the links between lncRNAs, brain development and brain-related diseases. Understanding the functions of lncRNAs in NSCs and brain organogenesis could revolutionize the basic principles of developmental biology and neuroscience.

Keywords: non-coding genome, regulatory RNAs, gene regulatory networks, neural differentiation, neurogenesis, gliogenesis, brain-related diseases

Introduction

A long standing question in biological sciences is how cell diversity, specification patterns, and tissue complexity are generated during organ development. The mammalian brain is the most complex organ of any living organism. The question of how this enormous complexity is generated is still open. Such complexity is the result of millions of years of evolution that have equipped neural stem/progenitor cells (NSCs/NPCs) in the embryo with the ability to generate every neuron and glial cell in the brain via a combined action of extrinsic morphogenetic cues and intrinsic gene regulatory networks. For long time, it was thought that these networks are mainly based on cross-regulatory interactions between transcription factors (TFs) (Jessell, 2000; Politis et al., 2008; Kaltezioti et al., 2010; Martynoga et al., 2012; Stergiopoulos and Politis, 2013). However, the recent advent of sequencing methodologies and experimental data from large-scale consortia focused on characterizing functional genomic elements such as ENCODE and FANTOM, have revolutionized our view for organization, activity, and regulation of the mammalian genome (Carninci et al., 2005; Katayama et al., 2005; Birney et al., 2007). Surprisingly, the vast majority of the genome is transcribed producing not only protein-coding RNAs but also a vast number of different kinds of newly-identified classes of non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs-small non-coding RNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). miRNAs have been extensively studied while the role of lncRNAs in cell biology together with novel roles of miRNAs in directly regulating lncRNAs have just begun to emerge (Amodio et al., 2012a,b; Rossi et al., 2013; Tay et al., 2014). LncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II, defined as endogenous cellular RNAs longer than 200 nt in length that lack an ORF, can be post-transcriptional processed by 5′ capping, polyadenylation, splicing, RNA editing, and exhibit specific sub-cellular localization (Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). Most importantly, it was recently shown that lncRNAs participate in the gene regulatory networks controlling embryonic stem cell (ESC) pluripotency and metastasis of cancer cells, as well as development and function of various tissues (Guttman et al., 2011; Gutschner and Diederichs, 2012; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012; Yang et al., 2013). Although lncRNAs are the most abundant classes of RNAs (Katayama et al., 2005; Birney et al., 2007; Kapranov et al., 2007b; Kapranov and St Laurent, 2012), they remain poorly characterized and their roles in brain development have just begun to arise. Notably, it has been proposed that the number of lncRNAs far exceeds the number of protein-coding mRNAs in the mammalian transcriptome (Carninci et al., 2005; Kapranov et al., 2010) and the vast majority of them appears to be expressed in adult brain in a highly specific manner (Qureshi and Mehler, 2012).

In the last few years, many groups have focused their efforts toward understanding the actions of lncRNAs in brain function and evolution. In this mini-review, we highlight the emerging evidence of the involvement of this new class of RNA molecules in NSC biology during development and adulthood, in health and disease. In particular, we summarize recent progress regarding the participation of lncRNAs in the regulatory networks that control the fine balance between proliferation and differentiation decisions of NSCs. The ability of lncRNAs to interact with both genomic loci and protein products of TF genes appears to endow them with a remarkable capacity to control NSC maintenance and differentiation, suggesting an undoubtedly important influence on the pathophysiology of several neurodegenerative disorders (Kapranov et al., 2007a,b; Guttman et al., 2009; Khalil et al., 2009; Orom et al., 2010; Bian and Sun, 2011; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012; Spadaro and Bredy, 2012; Ng et al., 2013).

LncRNAs: new players in cell biology

LncRNAs can be classified as bidirectional, intronic, intergenic, sense, antisense or 3′-UTR (untranslated region) transcripts with respect to nearby protein-coding genes (Mercer et al., 2009; Derrien et al., 2012). Some lncRNAs are exported from nucleus and perform important functions in the cytoplasm, but more often they are found in nucleus, particularly associated with chromatin (Saxena and Carninci, 2011). In more detail, these transcripts may be bound by proteins, other RNA molecules or even fulfil intrinsic catalytic functions (Fedor and Williamson, 2005; Ye, 2007; Guttman and Rinn, 2012). The vast majority of these transcripts are not translated, supporting a role as non-coding RNAs rather than protein precursors (Banfai et al., 2012; Derrien et al., 2012). Furthermore, lncRNAs are developmentally regulated, expressed in specific cell types, associated with chromatin signatures indicating transcriptional regulation, are under evolutionary constraint and associated with carcinogenesis and other diseases; all of which support meaningful roles of lncRNAs (Qureshi and Mehler, 2012; Fatica and Bozzoni, 2014). LncRNAs also participate in a striking diversity of cellular processes including transcriptional regulation, genomic imprinting, alternative splicing, mRNA stability, translational control, DNA damage response, cell cycle regulation and organelle biogenesis (Rinn and Chang, 2012). Interestingly, it seems that knock-down or over-expression of many of these lncRNAs produce phenotypes that are very well correlated with their aberrant expression in disease states (Qureshi et al., 2010; Gutschner and Diederichs, 2012; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). Therefore, we believe that lncRNA transcripts would eventually occupy a central place in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying human diseases.

Systematical profiling and comprehensive annotation of lncRNAs in various cell types can shed light on the functionalities of these novel regulators. LncRNA-protein interactions can be currently predicted, approached and analyzed by various research advanced tools and strategies apart from bioinformatics, including high-throughput analysis of lncRNA expression [microarrays, RNA sequencing [RNA-Seq] (Mortazavi et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Ilott and Ponting, 2013), RNA CaptureSeq, iSeeRNA [support vector machine (SVM)-based classifier] (Sun et al., 2013), BRIC-Seq [50-bromo-uridine (BrU) immunoprecipitation chase-deep sequencing analysis] (Imamachi et al., 2013)], RIP [RNA-binding protein (RBP) immunoprecipitation] coupled with microarray and high-throughput sequencing (RIP-Chip/Seq respectively) (Zhao et al., 2010; Jain et al., 2011), ChIRP (chromatin isolation by RNA purification) and CHART (capture hybridization analysis of RNA targets—High-throughput finding of RBPs and DNAs) as well as CLIP (crosslinking-immunopurification)-Seq, which provides transcriptome-wide coverage for mapping RBP-binding sites (Khalil et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010; Chu et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013).

LncRNAs in neural stem cells

These technologies have greatly helped the efforts to elucidate the role of lncRNAs in NSCs, neural differentiation, migration and maturation. Toward this goal, Ramos and colleagues identified and predicted regulatory roles for more than 12,000 novel lncRNAs (2,265 lncRNAs had proximal protein-coding gene neighbors) in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of adult mice. In FACS-sorted NSCs, they found a unique lncRNA expression pattern for each of the three stages of neurogenesis analyzed. Moreover, by using ChIP-Seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing), lncRNAs were shown to be transcriptionally regulated in a manner analogous to mRNAs, enabling the prediction of lncRNAs that may function in the glial-neuronal lineage specification of multipotent adult NSCs (Ramos et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Further transcriptome-next-generation-sequencing revealed that lncRNA-mediated alternative splicing of cell fate determinants controls stem-cell commitment during neurogenesis. Specifically, Aprea and co-workers identified several genic and intergenic lncRNAs that are functionally involved in neurogenic commitment, including Cosl1, Btg2-AS1, Gm17566, Miat (Myocardial infarction associated transcript-Gomafu), Rmst (Rhabdomyosarcoma 2 associated transcript), Gm17566, Gm14207, Gm16758, 2610307P16Rik, AC102815.1, C230034O21Rik and 9930014A18Rik (Aprea et al., 2013). Accordingly, subsequent studies using high-throughput transcriptomic data (microarray platform) to examine lncRNA differential expression in NSCs, GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes, led to the identification of lncRNAs that are dynamically regulated during neural lineage specification, neuronal-glia fate switching and oligodendrocyte maturation [i.e., Dlx1AS (Distal-less homeobox 1 antisense), Evf2 (Embryonic ventral forebrain 2), Rmst, utNgn1 (untranslated Neurogenin1), MALAT1 (metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; also named NEAT2)] (Mercer et al., 2010; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012; Ng et al., 2013). ChIP-Seq approaches were also developed to generate and investigate genome-wide chromatin-state maps. These functional analyses predicted hypothetical roles for 150 mammalian lincRNAs (long intergenic non-coding RNAs) in a “guilt-by-association” manner in NSCs. In particular, specific lincRNAs appeared to localize near genes encoding key TFs (such as Sox2, Klf4, Myc, p53, NFkB and Brn1) that are involved in processes ranging from hippocampal development to neuronal and oligodendrocyte maturation (Guttman et al., 2009; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012).

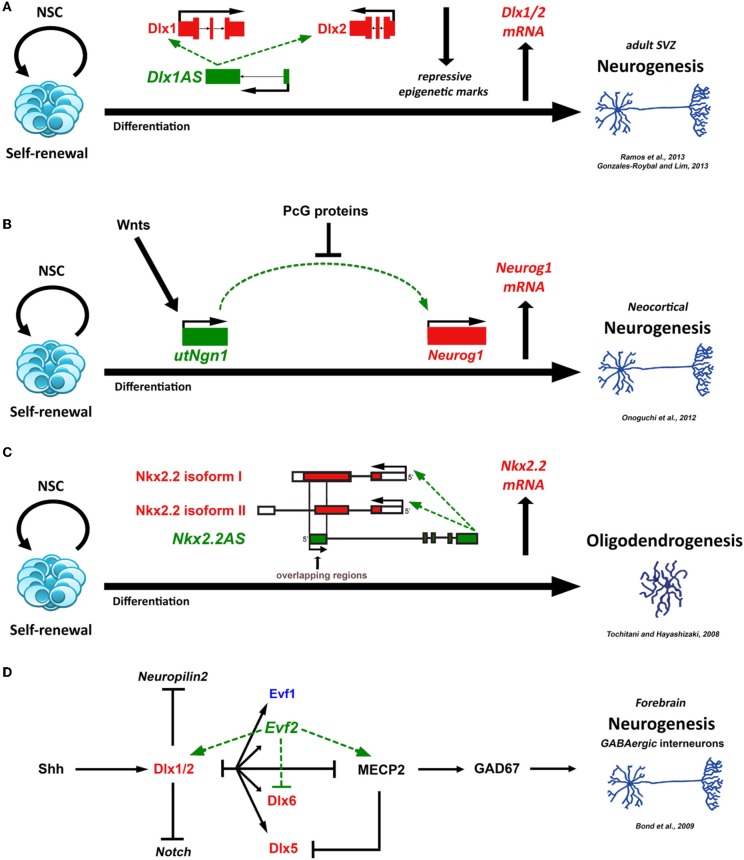

More concisely, Ramos et al. have also performed in vitro knock-down studies and observed that Dlx1AS, a lncRNA encoded from a bigene Dlx1/2 cluster, is associated with fate determination of adult SVZ NSCs via positive regulation of Dlx1 and Dlx2 gene expression. Mechanistically, enhanced transcription of Dlx1AS occurs during neurogenesis when H3K27me3 (trimethylation of histone H3 Lys-27) repression is decreased. The H3K27me3-specific demethylase JMJD3 was also found to be enriched at the Dlx1AS locus (Figure 1A) (Gonzales-Roybal and Lim, 2013; Ramos et al., 2013). Recently, a comprehensive study came up with the finding that UtNgn1 is a non-coding RNA transcribed from an enhancer region of the Neurogenin1 (Neurog1) locus. This non-coding transcript seems to positively regulate Neurog1 transcription during neuronal differentiation of NSCs. In detail, during the late stage of neocortical NSC development, utNgn1 expression is up-regulated via involvement of Wnt signaling whereas it is down-regulated by PcG (polycomb group) proteins (Figure 1B) (Onoguchi et al., 2012). Additionally, two lncRNAs, nuclear enriched abundant transcripts NEAT1 and NEAT2 (MALAT1) are up-regulated in neuronal and glial progeny, and are associated with neuronal activity, growth and branching (Mercer et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2013). Miat (also called Gomafu) is one of the known non-coding RNAs that participates in neuronal subtype- specific determination and is also highly expressed in oligodendrocyte lineage specification (Aprea et al., 2013). In the same lineage, another lncRNA, Nkx2.2AS, an antisense RNA of the known homeobox TF Nkx2.2, appears to lead NSCs into oligodendrocytic fate through modest induction of Nkx2.2 gene. By using deletion mutants, Tochitani and Hayashizaki showed that the overlapping regions of Nkx2.2AS and Nkx2.2 isoforms are required for promoting Nkx2.2 mRNA levels and the subsequent oligodendrocytic differentiation of NSCs (Figure 1C) (Tochitani and Hayashizaki, 2008). Evf2 is predominantly detected in the developing forebrain, both in human and mouse, and is critical for GABAergic-interneuron formation. Like other lncRNAs, Evf2 seems to control the expression of specific genes that are necessary during brain development, such as Dlx5, Dlx6 and Gad1, through distinct trans- and cis-acting mechanisms (Figure 1D) (Bond et al., 2009). Interestingly, Rmst is presented to be a novel marker for dopaminergic neurons during NSC differentiation, where it is co-expressed with the midbrain-specific TF Lmx1a (Uhde et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Proposed schematic models for the role of different lncRNAs (green) in neural development. (A) LncRNA Dlx1AS consists of two exons that are spliced and the mature transcript is polyadenylated. During neuronal differentiation of adult SVZ NSCs, Dlx1AS is required for the induction of Dlx1 and Dlx2 (red) gene expression (Gonzales-Roybal and Lim, 2013; Ramos et al., 2013). (B) During neocortical neurogenesis, utNgn1 receive Wnt signals (i.e., Wnt3a) to induce the expression of Neurog1 (red). PcG protein-mediated mechanisms (i.e., Ring1B, H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K9/K14ac) lead to the suppression of utNgn1 (Onoguchi et al., 2012). (C) The overlapping regions of Nkx2.2AS and Nkx2.2 isoforms (I and II-red) are necessary to promote Nkx2.2 mRNA levels and the subsequent oligodendrocytic differentiation of NSCs (Tochitani and Hayashizaki, 2008). (D) Mechanistic pathway for Evf2-dependent interactions crucial for forebrain development. Secreted Shh (Sonic hedgehog) promotes expression of Dlx1 and Dlx2 (red), which sequentially suppress Neuropilin2 and Notch signaling. Activation of Evf2 leads to the formation of a regulatory network together with Dlx's (red) and MECP2 (methyl CpG binding protein 2) that controls GAD67 and GABAergic-interneuron formation (Bond et al., 2009). NSC, neural stem cell; Evf1 (lncRNA) (blue), Embryonic ventral forebrain-1, Dlx6 antisense RNA 1 (Dlx6AS1).

Considering the tight connection between pluripotency of human ESCs and their differentiation into NSCs (ESC-derived NSCs) and subsequently into neurons, Ng and co-workers extensively showed that diverse lncRNAs are essential for ESC proliferation and neurogenesis through physical interaction with master TFs (e.g., Sox2). In detail, microarray data analysis led to the identification of 35 neuronal lncRNAs with important roles in neuronal differentiation, e.g., Rmst (AK056164, AF429305 and AF429306), lncRNA_N1 (AK124684), lncRNA_N2 (AK091713), lncRNA_N3 (AK055040, etc.). They also suggested that these lncRNAs are required for generation of neurons and suppression of gliogenesis by association with chromatin modifiers and nuclear proteins (Ng et al., 2012). In agreement, another study that aimed at identifying functional features of lncRNAs during ESC differentiation to adult cerebellum by utilizing RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq technologies, demonstrated that filtered novel lncRNAs are located close to protein-coding genes involved in functions such as neuronal differentiation and transcriptional regulation (Guttman et al., 2009; Lv et al., 2013). Particular studies have been successful in identifying anti-NOS2A as an antisense transcript of the NOS2A (Nitric oxide synthase 2 enzyme) gene, an isoform of the NOS protein which induces hESC differentiation into neurogenic precursors (Korneev et al., 2008). Specific expression pattern was also detected for Otx2c (Orthodenticle homeobox 2 c), an alternative splicing variant of the pre-mRNA Otx2 with a possible role in neural differentiation of hESCs (Liu et al., 2013). Another lncRNA that is correlated with the proliferation state of ESCs is lincRNA-Sox2, which is located at the promoter of Sox2 locus and is regulated by Sox2 and Oct4 (Guttman et al., 2009). Finally, a thorough targeted RNA-Seq analysis carried out using neurons derived from patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) showed that more than 1,500 lncRNAs are dynamically regulated during differentiation of iPSCs toward glutamatergic neurons. Particularly, the expression of 1,622 non-coding genes (lncRNAs/lincRNAs) was dramatically affected during conversion from iPSCs to differentiating neurons, while alternative splicing occurred. Significant alterations were also observed in the expression patterns of non-coding genes involved in neuropsychiatric disorders (Lin et al., 2011; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012; Akula et al., 2014).

LncRNAs in brain function, evolution and neurological diseases

The importance of lncRNAs in the brain is explicitly highlighted by the observation that most of them are expressed in the adult mammalian brain in highly regional-, cellular- and sub-cellular compartment-specific and neuronal activity dependent profiles (Mercer et al., 2008; Ponjavic et al., 2009; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). In fact, it seems that lncRNAs have played important roles in the evolution of the form and function of human brain, since the fastest evolving regions of the primate genome are non-coding sequences that generate lncRNAs implicated in the modulation of neuro-developmental genes (Pollard et al., 2006; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). The most dramatic of these regions, called HAR1 (human accelerated region 1), is part of a novel lncRNA gene (HAR1F) that is expressed specifically in Cajal–Retzius neurons in the developing human neocortex from 7 to 19 gestational weeks, a crucial period for cortical neuron-specification and migration. Additionally, analysis of highly conserved lncRNAs in birds, marsupials and eutherian mammals revealed a remarkable similarity in spatiotemporal expression profiles of orthologous lncRNAs, suggesting ancient roles during brain development (Chodroff et al., 2010). Moreover, lncRNAs directly modulate synaptic processes (MALAT1), protein synthesis (BC1), learning and memory (Tsx), and are associated with neuronal activity in mouse cortex (Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). In agreement with these effects on neurons, lncRNAs have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of neuro-developmental, neurodegenerative, neuro-immunological and neuro-oncological diseases/disorders. For instance, high levels of BC1/BC200 and BACE1-AS have been implicated in Alzheimer's disease (AD) while NEAT1's in Huntington's disease (HD). BC1/BC200 normally seems to selectively regulate local protein synthesis in post-synaptic dendritic compartments, by repressing translation via an elF4-A-dependent mechanism (Qureshi et al., 2010; Niland et al., 2012). De-regulation of BACE1-AS has been shown to be responsible for feed-forward induction of BACE1 (β-secretase); thus leading to amyloid β (Aβ) increased production and possible AD pathogenesis (Qureshi et al., 2010). Additionally, NEAT1 is a lncRNA known to be involved in cell death mechanisms. In particular, NEAT1 controls target gene transcription by protein sequestration into paraspeckles (stress-responsive sub-nuclear structures), a potentially dysfunctional pathway in HD progression. In accordance, Hirose and co-workers have very recently shown that NEAT1 transcriptional up-regulation leads to the enlargement of these structures after proteasome inhibition (Johnson, 2012; Hirose et al., 2014). Various lncRNAs have also been correlated with Parkinson's disease (PINK-AS1, UCHL1-AS1), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MSUR1), Down's syndrome (NRON) as well as with tumor progression (ANRIL, MALAT1, HOTAIR, NOS3AS) (Gutschner and Diederichs, 2012). A common theme emerging from all these cases is that lncRNAs control the expression of nearby protein-coding genes in cis and de-regulation of this relationship could lead to nervous system-related diseases. In agreement, brain-expressed lncRNAs are preferentially located adjacent to protein-coding genes that are also expressed in the brain and involved in transcriptional regulation and/or nervous system development (Mercer et al., 2008; Ponjavic et al., 2009). Many of these pairs often exhibited coordinated expression during developmental transitions. Therefore, it was suggested that these lncRNAs may influence the expression of the associated protein-coding genes similarly to previously characterized examples such as Nkx2.2AS, HOTAIR, p15AS, p21AS and Evf2.

Perspective links between lncRNAs and brain development

Over recent years, it has become more and more evident that lncRNAs play key roles in gene regulatory networks controlling nervous system development. To initially investigate this link, we bioinformatically screened numerous mouse genes encoding TFs with well-established roles in CNS (central nervous system) development for close proximity with lncRNA genes (based on publicly available data from UCSC genome-browser). Accordingly, we managed to identify 79 such TF genes encompassing 91 transcriptional units for lncRNA genes in close proximity (<3,000 base pairs-bp) (Table 1). In particular, 40.65% of these lncRNAs are bidirectional, 16.48% intronic, 9.89% intergenic, 12.08% sense, 15.38% antisense and 5.49% 3′-UTR. The majority of these lncRNAs have only been identified in genome-wide expression screens, are expressed in nervous system, and intriguingly, their functions are totally unknown. Some of them have been reported to interact with TFs or chromatin-associated complexes (Wang and Chang, 2011; Guttman and Rinn, 2012; Rinn and Chang, 2012), indicating potential contribution to the combinatorial transcriptional codes involved in NSC maintenance, sub-type/lineage specification and terminal differentiation. Based on these preliminary evidence, we postulate that lncRNAs and TFs with regulatory role in neurogenesis are inter-connected and may form coherent cross-regulatory networks that are associated with CNS development. However, this hypothesis needs to be extensively interrogated in NSCs. Moreover, considering the fact that some TFs are used as reprogramming tools for the production of iPSCs, induced neurons, induced NSCs, cardiomyocytes, etc. (Yang et al., 2011), these lncRNAs may be utilized for the production of clinically useful cell types in the near feature, revolutionizing the basic principles of developmental/cell biology as well as neuroscience.

Table 1.

List of genes encoding TFs with critical roles in brain development that also contain lncRNA genes in close proximity to their genomic loci (<3,000 bp).

| Genes encoding for TFs | LncRNAs | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Ascl4 | AK018959 | Sense |

| Atoh7 | AK005214 | Sense |

| Crebbp | 4930455F16Rik | Intergenic |

| Crx | CrxOS | Bidirectional |

| Ctnnb1 | 4930593C16Rik | Bidirectional |

| Cux2 | AK006762 | Sense |

| Cux2 | AK187608 | Bidirectional |

| Dlx1 | Dlx1AS | Antisense |

| Dlx4 | A730090H04Rik | Bidirectional |

| Dlx6 | Dlx6AS1 | Antisense |

| Dlx6 | Dlx6AS2 | Intronic |

| Emx2 | Emx2OS | Bidirectional |

| Evx1 | 5730457N03Rik | Bidirectional |

| FezF1 | FezF1-AS1 | Bidirectional |

| FezF1 | AK086573 | Intergenic |

| FoxA2 | AK156045 | Antisense |

| FoxG1 | AK158887 | Intergenic |

| FoxG1 | 3110039M20Rik | Sense |

| Gata1 | S57880 | Sense |

| Gata2 | AK137172 | Sense |

| Gata3 | 4930412013R | Bidirectional |

| Gata4 | AK031341 | Intronic |

| Gata6 | AK033147 | Bidirectional |

| Gata6 | AK003136 | Bidirectional |

| Gbx2 | D130058E05Rik | Bidirectional |

| Gli1 | AK157048 | Sense |

| Gli2 | AK054469 | Intronic |

| Gli3 | AK135998 | Intergenic |

| Hmx1 | E130018O15Rik | Bidirectional |

| Irx2 | Gm20554 | Bidirectional |

| Lef1 | Lef1-AS1 | Bidirectional |

| Lhx1 | Lhx1OS | Bidirectional |

| Lhx3 | AK035055 | Bidirectional |

| Lhx8 | AI606473 | Bidirectional |

| Lmx1b | C130021I20 | Bidirectional |

| Lxrb (NR1H2) | AK184603 | 3 ′-UTR |

| Meis1 | AK144295 | Antisense |

| Meis2 | AK012325 | Sense |

| Meis2 | AK144367 | Bidirectional |

| Meis2 | AK144485 | Bidirectional |

| Msx1 | Msx1AS | Antisense |

| MycN | MYCNOS | Bidirectional |

| Myt1L | AK138505 | Antisense |

| NFATc1 | AK155068 | 3 ′-UTR |

| NFATc4 | AK014164 | Sense |

| NFIA | E130114P18Rik | Bidirectional |

| NFIB | AK081607 | Intronic |

| NFIx | AK168184 | Antisense |

| NFkB2 | AK029443 | Bidirectional |

| Ngn1 | AK016084 | Intergenic |

| Nkx2.2 | Nkx2.2AS | Antisense |

| Notch1 | AK075572 | Antisense |

| NR2F1 | AK051417 | Intergenic |

| NR2F1 | A830082K12Rik | Bidirectional |

| NR2F2 | AK135306 | Intronic |

| NR3C2 | Gm10649 | Bidirectional |

| NR4A2 | BB557941 | Intergenic |

| NR5A2 (lrh-1) | AK178198 | Antisense |

| NR5A2 (lrh-1) | AK145521 | Intronic |

| Otx2 | Otx2OS | Bidirectional |

| Pax2 | AK006641 | Antisense |

| Pax6 | AK044354 | Antisense |

| Pbx3 | AK138624 | Intronic |

| Pou4F1 | AK084042 | Intergenic |

| PPARd | AK033897 | Intronic |

| PPARd | AK007468 | Intronic |

| Prox1 | AK142161 | Bidirectional |

| Ptf1a | AK053418 | Antisense |

| RARa | AK031732 | Intronic |

| RARb | AK052306 | 3 ′-UTR |

| RBPjK | AK164362 | Intronic |

| Runx1 | AK131747 | Intergenic |

| SATB2 | 9130024F11Rik | Bidirectional |

| Six1 | AK035085 | 3 ′-UTR |

| Six3 | Six3OS1 | Bidirectional |

| Six6 | 4930447C04Rik | Bidirectional |

| Sox1 | Gm5607 | Sense |

| Sox10 | GM10863 | Bidirectional |

| Sox2 | Sox2OT | Sense |

| Sox21 | AK039417 | Bidirectional |

| Sox8 | AK079380 | Bidirectional |

| Sox9 | BC006965 | Bidirectional |

| STAT5b | AK088966 | Intronic |

| Tgif2 | 5430405H02Rik | 3 ′-UTR |

| THRA | AK165172 | Intronic |

| THRB | AK088911 | Antisense |

| WT1 | AK033304 | Intronic |

| WT1 | AI314831 | Bidirectional |

| Zeb1 | AK041408 | Intronic |

| Zeb1 | Gm10125 | Bidirectional |

| Zeb2 | Zeb2OS | Bidirectional |

Some of these TFs contain more than one lncRNA near to their genes (duplicates). The position of each lncRNA relatively to its nearby protein-coding gene is indicated at the third column of the table.

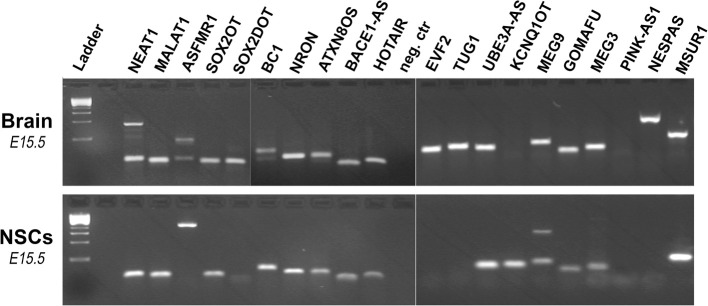

To further examine the links between lncRNAs, brain development and neurological disorders, we tested whether lncRNAs, associated with nervous system-related diseases in humans, are expressed in embryonic mouse brain (E15.5) or ex vivo cultured NSCs (isolated from mouse telencephalon, E15.5). The rational for these experiments was based on observations showing many neurological diseases to be initiated very early during brain maturation and development (Bian and Sun, 2011; Qureshi and Mehler, 2012). Specifically, we first identified in silico and then tested for expression 20 such lncRNAs with clear conservation in mouse genome. Interestingly, RT-PCR (reverse transcription-PCR) analysis revealed that most lncRNAs are expressed in both brain and NSCs (Figure 2), suggesting potential involvement in brain development. Moreover, a possible function of these lncRNAs in NSCs may contribute to their roles in neurological diseases. Nevertheless, further investigation and initiation of new experimental studies are needed to uncover the exact function of lncRNAs in NSCs and nervous system in general.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR-based detection of various lncRNAs associated with CNS-related diseases or disorders. Experiments were performed using cDNA samples derived from embryonic mouse brain (E15.5) or NSCs isolated from embryonic mouse telencephalon and cultured ex vivo, as indicated. In some cases alternative splicing isoforms are also evident. RT-PCR primer sequences are available upon request.

Conclusions

LncRNAs represent a new exciting frontier in molecular biology with major roles in NSC fate decisions, specification and commitment. Full understanding of how these non-coding transcripts regulate the expression of protein-coding genes and participate in gene regulatory circuitries could lead to the discovery of novel cellular/molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in neural development; thus having potential implications for the treatment of nervous system-related diseases and traumas.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by ARISTEIA-II (NeuroNetwk, No. 4786), IKYDA (Greek Ministry of Education) and Fondation Santé grants to Panagiotis K. Politis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- lincRNA

large intergenic non-coding RNA

- miRNA

microRNA

- NSCs

neural stem cells

- ESCs

embryonic stem cells

- iPSCs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- CNS

central nervous system

- SVZ

subventricular zone

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- RBP

RNA binding protein

- RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing

- RIP-Chip

RBP immunoprecipitation-microarray (Chip)

- ChIRP

chromatin isolation by RNA precipitation

- CHART

capture hybridization analysis of RNA targets

- CLIP

crosslinking-immunopurification

- UCSC

University of California Santa Cruz

- ORFs

open reading frames

- TFs

transcription factors

- HAR1

human accelerated region 1

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- HD

Huntington's disease

- Dlx1AS

distal-less homeobox 1 antisense

- Miat

myocardial infarction associated transcript

- Rmst

rhabdomyosarcoma 2 associated transcript

- Evf2

embryonic ventral forebrain 2

- UtNgn1

untranslated neurogenin1

- NEAT

non-coding nuclear enriched abundant transcript.

References

- Akula N., Barb J., Jiang X., Wendland J. R., Choi K. H., Sen S. K., et al. (2014). RNA-sequencing of the brain transcriptome implicates dysregulation of neuroplasticity, circadian rhythms and GTPase binding in bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/mp.2013.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio N., Di Martino M. T., Foresta U., Leone E., Lionetti M., Leotta M., et al. (2012a). miR-29b sensitizes multiple myeloma cells to bortezomib-induced apoptosis through the activation of a feedback loop with the transcription factor Sp1. Cell Death Dis. 3, e436 10.1038/cddis.2012.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio N., Leotta M., Bellizzi D., Di Martino M. T., D'Aquila P., Lionetti M., et al. (2012b). DNA-demethylating and anti-tumor activity of synthetic miR-29b mimics in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 3, 1246–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprea J., Prenninger S., Dori M., Ghosh T., Monasor L. S., Wessendorf E., et al. (2013). Transcriptome sequencing during mouse brain development identifies long non-coding RNAs functionally involved in neurogenic commitment. EMBO J. 32, 3145–3160 10.1038/emboj.2013.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfai B., Jia H., Khatun J., Wood E., Risk B., Gundling W. E., et al. (2012). Long noncoding RNAs are rarely translated in two human cell lines. Genome Res. 22, 1646–1657 10.1101/gr.134767.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian S., Sun T. (2011). Functions of noncoding RNAs in neural development and neurological diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 44, 359–373 10.1007/s12035-011-8211-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Dutta A., Guigo R., Gingeras T. R., Margulies E. H., et al. (2007). Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 10.1038/nature05874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A. M., Vangompel M. J., Sametsky E. A., Clark M. F., Savage J. C., Disterhoft J. F., et al. (2009). Balanced gene regulation by an embryonic brain ncRNA is critical for adult hippocampal GABA circuitry. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1020–1027 10.1038/nn.2371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P., Kasukawa T., Katayama S., Gough J., Frith M. C., Maeda N., et al. (2005). The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309, 1559–1563 10.1126/science.1112014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodroff R. A., Goodstadt L., Sirey T. M., Oliver P. L., Davies K. E., Green E. D., et al. (2010). Long noncoding RNA genes: conservation of sequence and brain expression among diverse amniotes. Genome Biol. 11:R72 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C., Qu K., Zhong F. L., Artandi S. E., Chang H. Y. (2011). Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol. Cell 44, 667–678 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T., Johnson R., Bussotti G., Tanzer A., Djebali S., Tilgner H., et al. (2012). The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 22, 1775–1789 10.1101/gr.132159.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatica A., Bozzoni I. (2014). Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 7–21 10.1038/nrg3606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedor M. J., Williamson J. R. (2005). The catalytic diversity of RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 399–412 10.1038/nrm1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Roybal G., Lim D. A. (2013). Chromatin-based epigenetics of adult subventricular zone neural stem cells. Front. Genet. 4:194 10.3389/fgene.2013.00194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T., Diederichs S. (2012). The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 9, 703–719 10.4161/rna.20481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M., Amit I., Garber M., French C., Lin M. F., Feldser D., et al. (2009). Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature 458, 223–227 10.1038/nature07672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M., Donaghey J., Carey B. W., Garber M., Grenier J. K., Munson G., et al. (2011). lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature 477, 295–300 10.1038/nature10398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M., Rinn J. L. (2012). Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature 482, 339–346 10.1038/nature10887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T., Virnicchi G., Tanigawa A., Naganuma T., Li R., Kimura H., et al. (2014). NEAT1 long noncoding RNA regulates transcription via protein sequestration within subnuclear bodies. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 169–183 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilott N. E., Ponting C. P. (2013). Predicting long non-coding RNAs using RNA sequencing. Methods 63, 50–59 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamachi N., Tani H., Mizutani R., Imamura K., Irie T., Suzuki Y., et al. (2013). BRIC-seq: a genome-wide approach for determining RNA stability in mammalian cells. Methods. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R., Devine T., George A. D., Chittur S. V., Baroni T. E., Penalva L. O., et al. (2011). RIP-Chip analysis: RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation-Microarray (Chip) Profiling. Methods Mol. Biol. 703, 247–263 10.1007/978-1-59745-248-9_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell T. M. (2000). Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1, 20–29 10.1038/35049541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. (2012). Long non-coding RNAs in Huntington's disease neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 245–254 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltezioti V., Kouroupi G., Oikonomaki M., Mantouvalou E., Stergiopoulos A., Charonis A., et al. (2010). Prox1 regulates the notch1-mediated inhibition of neurogenesis. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000565 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P., Cheng J., Dike S., Nix D. A., Duttagupta R., Willingham A. T., et al. (2007a). RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science 316, 1484–1488 10.1126/science.1138341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P., St Laurent G. (2012). Dark matter RNA: existence, function, and controversy. Front. Genet. 3:60 10.3389/fgene.2012.00060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P., St Laurent G., Raz T., Ozsolak F., Reynolds C. P., Sorensen P. H., et al. (2010). The majority of total nuclear-encoded non-ribosomal RNA in a human cell is “dark matter” un-annotated RNA. BMC Biol. 8:149 10.1186/1741-7007-8-149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P., Willingham A. T., Gingeras T. R. (2007b). Genome-wide transcription and the implications for genomic organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 413–423 10.1038/nrg2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama S., Tomaru Y., Kasukawa T., Waki K., Nakanishi M., Nakamura M., et al. (2005). Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science 309, 1564–1566 10.1126/science.1112009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil A. M., Guttman M., Huarte M., Garber M., Raj A., Rivea Morales D., et al. (2009). Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 11667–11672 10.1073/pnas.0904715106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korneev S. A., Korneeva E. I., Lagarkova M. A., Kiselev S. L., Critchley G., O'Shea M. (2008). Novel noncoding antisense RNA transcribed from human anti-NOS2A locus is differentially regulated during neuronal differentiation of embryonic stem cells. RNA 14, 2030–2037 10.1261/rna.1084308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Pedrosa E., Shah A., Hrabovsky A., Maqbool S., Zheng D., et al. (2011). RNA-Seq of human neurons derived from iPS cells reveals candidate long non-coding RNAs involved in neurogenesis and neuropsychiatric disorders. PLoS ONE 6:e23356 10.1371/journal.pone.0023356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Chi L., Fang Y., Liu L., Zhang X. (2013). Specific expression pattern of a novel Otx2 splicing variant during neural differentiation. Gene 523, 33–38 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J., Liu H., Huang Z., Su J., He H., Xiu Y., et al. (2013). Long non-coding RNA identification over mouse brain development by integrative modeling of chromatin and genomic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 10044–10061 10.1093/nar/gkt818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynoga B., Drechsel D., Guillemot F. (2012). Molecular control of neurogenesis: a view from the mammalian cerebral cortex. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4:a008359 10.1101/cshperspect.a008359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer T. R., Dinger M. E., Mattick J. S. (2009). Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 155–159 10.1038/nrg2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer T. R., Dinger M. E., Sunkin S. M., Mehler M. F., Mattick J. S. (2008). Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 716–721 10.1073/pnas.0706729105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer T. R., Qureshi I. A., Gokhan S., Dinger M. E., Li G., Mattick J. S., et al. (2010). Long noncoding RNAs in neuronal-glial fate specification and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation. BMC Neurosci. 11:14 10.1186/1471-2202-11-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B. (2008). Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5, 621–628 10.1038/nmeth.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S. Y., Johnson R., Stanton L. W. (2012). Human long non-coding RNAs promote pluripotency and neuronal differentiation by association with chromatin modifiers and transcription factors. EMBO J. 31, 522–533 10.1038/emboj.2011.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S. Y., Lin L., Soh B. S., Stanton L. W. (2013). Long noncoding RNAs in development and disease of the central nervous system. Trends Genet. 29, 461–468 10.1016/j.tig.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niland C. N., Merry C. R., Khalil A. M. (2012). Emerging roles for long non-coding rnas in cancer and neurological disorders. Front. Genet. 3:25 10.3389/fgene.2012.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoguchi M., Hirabayashi Y., Koseki H., Gotoh Y. (2012). A noncoding RNA regulates the neurogenin1 gene locus during mouse neocortical development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16939–16944 10.1073/pnas.1202956109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orom U. A., Derrien T., Beringer M., Gumireddy K., Gardini A., Bussotti G., et al. (2010). Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell 143, 46–58 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politis P. K., Thomaidou D., Matsas R. (2008). Coordination of cell cycle exit and differentiation of neuronal progenitors. Cell Cycle 7, 691–697 10.4161/cc.7.6.5550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. S., Salama S. R., Lambert N., Lambot M. A., Coppens S., Pedersen J. S., et al. (2006). An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature 443, 167–172 10.1038/nature05113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponjavic J., Oliver P. L., Lunter G., Ponting C. P. (2009). Genomic and transcriptional co-localization of protein-coding and long non-coding RNA pairs in the developing brain. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000617 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi I. A., Mattick J. S., Mehler M. F. (2010). Long non-coding RNAs in nervous system function and disease. Brain Res. 1338, 20–35 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi I. A., Mehler M. F. (2012). Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in brain evolution, development, plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 528–541 10.1038/nrn3234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A. D., Diaz A., Nellore A., Delgado R. N., Park K. Y., Gonzales-Roybal G., et al. (2013). Integration of genome-wide approaches identifies lncRNAs of adult neural stem cells and their progeny in vivo. Cell Stem Cell 12, 616–628 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn J. L., Chang H. Y. (2012). Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 145–166 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M., Pitari M. R., Amodio N., Di Martino M. T., Conforti F., Leone E., et al. (2013). miR-29b negatively regulates human osteoclastic cell differentiation and function: implications for the treatment of multiple myeloma-related bone disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 228, 1506–1515 10.1002/jcp.24306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A., Carninci P. (2011). Long non-coding RNA modifies chromatin: epigenetic silencing by long non-coding RNAs. Bioessays 33, 830–839 10.1002/bies.201100084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro P. A., Bredy T. W. (2012). Emerging role of non-coding RNA in neural plasticity, cognitive function, and neuropsychiatric disorders. Front. Genet. 3:132 10.3389/fgene.2012.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiopoulos A., Politis P. K. (2013). The role of nuclear receptors in controlling the fine balance between proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 534, 27–37 10.1016/j.abb.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Chen X., Jiang P., Song X., Wang H., Sun H. (2013). iSeeRNA: identification of long intergenic non-coding RNA transcripts from transcriptome sequencing data. BMC Genomics 14(Suppl. 2):S7 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S2-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay Y., Rinn J., Pandolfi P. P. (2014). The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature 505, 344–352 10.1038/nature12986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tochitani S., Hayashizaki Y. (2008). Nkx2.2 antisense RNA overexpression enhanced oligodendrocytic differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 372, 691–696 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhde C. W., Vives J., Jaeger I., Li M. (2010). Rmst is a novel marker for the mouse ventral mesencephalic floor plate and the anterior dorsal midline cells. PLoS ONE 5:e8641 10.1371/journal.pone.0008641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lucas B. A., Maquat L. E. (2013). New gene expression pipelines gush lncRNAs. Genome Biol. 14:117 10.1186/gb-2013-14-5-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. C., Chang H. Y. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 43, 904–914 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Gerstein M., Snyder M. (2009). RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 57–63 10.1038/nrg2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. Q., Habegger L., Noisa P., Szekely A., Qiu C., Hutchison S., et al. (2010). Dynamic transcriptomes during neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells revealed by short, long, and paired-end sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5254–5259 10.1073/pnas.0914114107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Lin C., Jin C., Yang J. C., Tanasa B., Li W., et al. (2013). lncRNA-dependent mechanisms of androgen-receptor-regulated gene activation programs. Nature 500, 598–602 10.1038/nature12451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N., Ng Y. H., Pang Z. P., Sudhof T. C., Wernig M. (2011). Induced neuronal cells: how to make and define a neuron. Cell Stem Cell 9, 517–525 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K. (2007). H/ACA guide RNAs, proteins and complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 287–292 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Ohsumi T. K., Kung J. T., Ogawa Y., Grau D. J., Sarma K., et al. (2010). Genome-wide identification of polycomb-associated RNAs by RIP-seq. Mol. Cell 40, 939–953 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Fu H., Wu Y., Zheng X. (2013). Function of lncRNAs and approaches to lncRNA-protein interactions. Sci. China Life Sci. 56, 876–885 10.1007/s11427-013-4553-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]