Abstract

Background: whether socioeconomic position over the life course influences the wellbeing of older people similarly in different societies is not known.

Objective: to investigate the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction among individuals in early old age and the influence of the welfare state regime on the associations.

Design: comparative study using data from Wave 2 and SHARELIFE, the retrospective Wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), collected during 2006–07 and 2008–09, respectively.

Setting: thirteen European countries representing four welfare regimes (Southern, Scandinavian, Post-communist and Bismarckian).

Subjects: a total of 17,697 individuals aged 50–75 years.

Methods: slope indices of inequality (SIIs) were calculated for the association between life course socioeconomic position (measured by the number of books in childhood, education level and current wealth) and life satisfaction. Single level linear regression models stratified by welfare regime and multilevel regression models, containing interaction terms between socioeconomic position and welfare regime type, were calculated.

Results: socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction were present in all welfare regimes. Educational inequalities in life satisfaction were narrowest in Scandinavian and Bismarckian regimes among both genders. Post-communist and Southern countries experienced both lower life satisfaction and larger socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction, using most measures of socioeconomic position. Current wealth was associated with large inequalities in life satisfaction across all regimes.

Conclusions: Scandinavian and Bismarckian countries exhibited narrower socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction. This suggests that more generous welfare states help to produce a more equitable distribution of wellbeing among older people.

Keywords: socioeconomic factors, welfare, ageing, satisfaction, quality of life, older people

Introduction

Improving mental wellbeing throughout the life course is recognised as an important component of healthy ageing [1]. Healthy ageing is influenced by an individual's socioeconomic position throughout the life course [2, 3], but also by societal level factors such as the welfare state [4, 5]. Early old age, containing both the retired and those in the final stages of working life, is increasingly acknowledged as an important stage of the life course, as the labour force across Europe is becoming older [1]. Measuring wellbeing and its determinants among this population is therefore considered a high policy priority.

The welfare state is thought to be a major determinant of the patterning of inequalities in health and wellbeing [4], as it may modify the effect of socioeconomic position on these outcomes. It is unlikely that any single aspect of the welfare state is responsible for wellbeing, but rather its influence is likely to arise as a result of a combination of policies. Five welfare regimes have been characterised within Europe. These are based on the differing contributions of the family, market, and state to the welfare of individuals within a country [6]. Southern countries (including Spain and Greece) typically have fragmented income maintenance schemes and exhibit high dependency on the family and voluntary sector [7, 8]. Scandinavian countries are characterised by a more interventionist state that seeks to promote social equality via principles of redistribution, universalism, a commitment to full employment and income-protection [6, 9]. Germany and France exemplify Bismarckian regimes. Benefits are usually earnings-related and administered by the employer, a supportive role for the family is encouraged, and social divisions are maintained [6]. Post-communist countries (including Poland and the Czech Republic) are characterised by their transition from communism to market economies and have social security systems which provide limited coverage [10]. The UK and Ireland are considered to be part of a ‘Liberal’ regime type, characterised by market dominance and modest state benefits, which are often means-tested [11].

Our study aims to first examine the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction among Europeans in early old age, using measures of socioeconomic position from across the life course. Second, we investigate the influence of the type of welfare regime on socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction.

Methods

Data source

Data were taken from Wave 2 (release 2.5.0) and SHARELIFE (release 1.0.0), the retrospective Wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) collected during 2006–07 and 2008–09, respectively. SHARE is a longitudinal panel survey, which collected representative data from individuals aged 50 and over in 13 European countries. Further information about SHARE is found elsewhere [12, 13]. The population studied included individuals in early old age (50–75 years) participating in Wave 2 and SHARELIFE, who were born in their current country of residence (n = 18,324).

Outcome variable

During Wave 2 participants were asked: ‘On a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 means completely dissatisfied and 10 means completely satisfied, how satisfied are you with your life?’ Life satisfaction is a valid measure of wellbeing, which contains substantial information about how individuals evaluate their lives [14]. Life satisfaction was treated as a continuous variable to ease the interpretation and comparison of results [15, 16].

Exposure variables

Childhood socioeconomic position was captured by the number of books in the household when the participant was aged 10 years, collected via retrospective recall. Education level was recorded using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97) [17]. Current household wealth (equivalised) was derived from a series of questions relating to financial and real assets, as well as liabilities [18]. Countries were grouped into four welfare regimes: Southern (Greece, Italy and Spain), Scandinavian (Denmark and Sweden), Post-communist (Czech Republic and Poland) and Bismarckian (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland).

Statistical analyses

To quantify socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction, slope indices of inequality (SIIs) were calculated [19]. Each measure of socioeconomic position was ranked from the least advantaged to the most advantaged (with the mid-point of their range in the cumulative distribution used for each category) [20]. These were standardised to produce a rank, where the theoretically most advantaged had a value of 1 and least advantaged a value of 0. The SII was calculated by running linear regression models using the socioeconomic rank to predict the outcome measure. It can be understood as the difference in mean life satisfaction between the hypothetically least and most socioeconomically advantaged. Since socioeconomic distributions varied by country, gender and cohort (pre-1946 and post-1945) separate ranks were calculated for each of these groups. Relative indices of inequality by gender and welfare regime were also calculated by dividing the SII by the mean life satisfaction.

Single level linear regression models stratified by welfare regime and containing country fixed effects were run to calculate the SIIs. Multilevel (random-intercept) regression models were also calculated to test the statistical interaction between the welfare regime type and socioeconomic position. All analyses were stratified by gender and adjusted for age group in 5-year bands. Further methodological details available in the Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix S1.

Results

The highest level of life satisfaction was found in Scandinavian countries and the lowest in Post-communist countries (Table 1). Full-descriptive statistics are found in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix S2. Table 1 displays the SIIs for each measure of socioeconomic position stratified by welfare regime (results from the multilevel models are found in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix S3). Narrower socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction were found in Scandinavia, when examining the effect of the number of books in childhood. For men in Scandinavia, the SII was 0.08 (95% CI: −0.18 to 0.35) and for women 0.13 (95% CI: −0.11 to 0.37). Differences in life satisfaction between welfare regimes were most apparent at the least advantaged end of the socioeconomic ranking and narrowed as the rank increased (Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix S4). SIIs were larger in each of the other regimes among both genders, largest for men in the Post-communist regime and for women in the Southern regime.

Table 1.

Mean life satisfaction and slope indices of inequality by welfare regime and gender for each measure of socioeconomic position

| Southern |

Scandinavian |

Post-communist |

Bismarckian |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| 7.56 | 1.56 | 8.44 | 1.34 | 6.94 | 1.98 | 7.76 | 1.55 | |

| SII | 95% CI | SII | 95% CI | SII | 95% CI | SII | 95% CI | |

| Number of books in childhood | 0.49 | (0.23, 0.76) | 0.08 | (−0.18, 0.35) | 0.92 | (0.52, 1.32) | 0.49 | (0.31, 0.66) |

| Education level | 0.74 | (0.47, 1.01) | 0.37 | (0.09, 0.65) | 1.11 | (0.70, 1.52) | 0.54 | (0.36, 0.72) |

| Current wealth | 1.08 | (0.86, 1.29) | 0.73 | (0.48, 0.99) | 1.19 | (0.83, 1.55) | 0.75 | (0.58, 0.91) |

| N | 2,326 | 1,272 | 1,226 | 3,220 | ||||

| Women | ||||||||

| 7.18 | 1.77 | 8.46 | 1.34 | 6.52 | 2.10 | 7.62 | 1.70 | |

| SII | 95% CI | SII | 95% CI | SII | 95% CI | SII | 95% CI | |

| Number of books in childhood | 1.10 | (0.83, 1.36) | 0.13 | (−0.11, 0.37) | 0.96 | (0.60, 1.33) | 0.53 | (0.35, 0.70) |

| Education level | 1.22 | (0.93, 1.51) | 0.13 | (−0.13, 0.38) | 1.39 | (1.00, 1.77) | 0.42 | (0.23, 0.60) |

| Current wealth | 1.09 | (0.87, 1.31) | 0.67 | (0.44, 0.91) | 1.47 | (1.14, 1.80) | 1.00 | (0.83, 1.16) |

| N | 2,743 | 1,429 | 1,613 | 3,868 | ||||

CI, confidence interval; N, number of individuals; SD, standard deviation; SII, slope index of inequality.

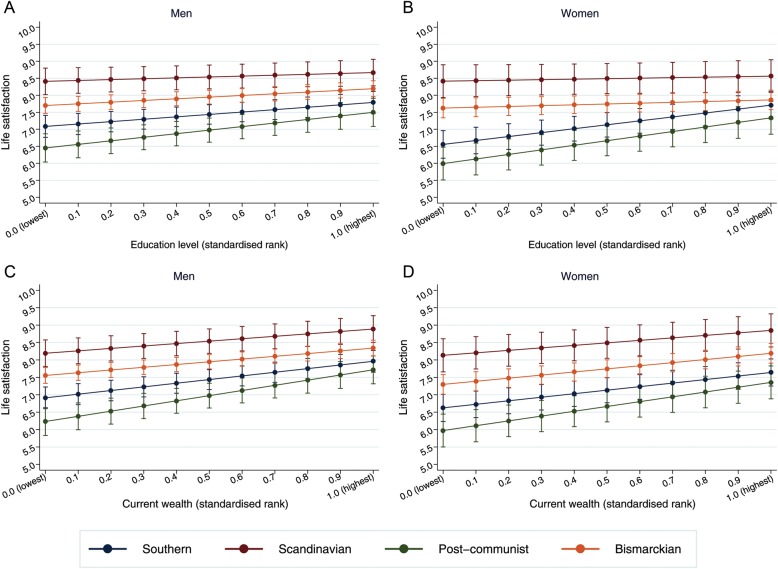

Narrowest educational inequalities in life satisfaction were found among men and women in Scandinavia (Figure 1A and B). The SII for men in Scandinavia was 0.37 (95% CI: 0.09 to 0.65) and for women 0.13 (95% CI: −0.13 to 0.38). Among both genders, the Bismarckian regime also exhibited relatively narrow inequalities in life satisfaction. Largest education SIIs were found in the Post-communist regime for both men (SII = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.70 to 1.52) and women (SII = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.77).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted predicted mean life satisfaction (with 95% confidence intervals) by education level and current wealth for men (n = 8,044) and women (n = 9,653) in different welfare regimes.

Wealth inequalities in life satisfaction were smallest in Scandinavia for both genders (Figure 1C and D). However, the SIIs for wealth were mostly larger across all regimes compared with the other measures. In Scandinavia, the SII for men was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.48 to 0.99) and for women 0.67 (95% CI: 0.44 to 0.91). These were not much larger in the Bismarckian regime and were largest in the Post-communist regime. Scandinavian countries also exhibited the narrowest relative inequalities in life satisfaction (Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix S5). For most measures of socioeconomic position, the Bismarckian regime also displayed narrower relative inequalities compared with Southern and Post-communist countries.

Discussion

Socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction among Europeans in early old age were present in all welfare regimes. The Scandinavian welfare regime exhibited the narrowest inequalities in life satisfaction, using all three measures of socioeconomic position from across the life course. Post-communist countries generally exhibited the largest socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction. Inequalities in life satisfaction were largest using current wealth in most regimes, but inequalities by education level were large, particularly among women in the Post-communist and Southern regimes. Highest levels of life satisfaction were also found in the Scandinavian regime and the lowest in the Post-communist regime.

This study has a number of strengths, including the utilisation of high quality and comparable survey data. Potential limitations include the risk of attrition and survival bias. However, the expected direction of bias is likely to underestimate the magnitude of inequalities [21–23]. Few studies have investigated the influence of the welfare regime on socioeconomic inequalities in wellbeing among older populations, with most studies using negative measures of health. Socioeconomic inequalities in poor self-rated health were found to be narrower in Nordic countries [24, 25], but others have had contradictory results [26, 27].

Our results have important implications for future research and policy, especially given the recent welfare policy changes across Europe [28]. As life satisfaction captures one aspect of wellbeing, further research using different indicators is needed to check the consistency of findings. The differing magnitude of inequalities by measure of socioeconomic position highlights the importance of using multiple measures when quantifying inequalities in health, especially among older populations. We recommend future research examines the impact of changes to welfare policy to try and unpack which policies may foster a more equitable distribution of wellbeing. Our findings suggest that mechanisms to buffer the effect of socioeconomic disadvantage in early old age specifically, perhaps through more redistributive fiscal policy and universal pensions, may help to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction for this age group.

Key points.

Wellbeing is an important component of healthy ageing and is influenced by socioeconomic position across the life course.

Socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction were most apparent in Post-communist and Southern countries.

Scandinavian and Bismarckian regimes exhibited narrowest absolute and relative inequalities in life satisfaction.

Welfare policy that buffers the effect of low socioeconomic position may help reduce socioeconomic inequalities in wellbeing.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study is an analysis of previously collected data and therefore ethical approval was not required for this study. Ethical approval for the survey was obtained by the SHARE team, see http://share-dev.mpisoc.mpg.de/ for details.

Funding

This work received no specific funding. At the time of the research, S.V.K. was funded by the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Health Directorates as part of the Evaluating Social Interventions programme at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit (25605200 68093). The funders had no influence over the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the paper or decision to submit. This paper uses data from SHARE wave 2 release 2.5.0, as of 24 May 2011 and SHARELIFE release 1, as of 24 November 2010. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through the 5th Framework Programme (project QLK6-CT-2001-00360 in the thematic programme Quality of Life), through the 6th Framework Programme (projects SHARE-I3, RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE, CIT5- CT-2005-028857 and SHARELIFE, CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and through the 7th Framework Programme (SHARE-PREP, N° 211909, SHARE-LEAP, N° 227822 and SHARE M4, N° 261982). Additional funding from the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01 AG09740-13S2, P01 AG005842, P01 AG08291, P30 AG12815, R21 AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG BSR06-11 and OGHA 04-064) and the German Ministry of Education and Research as well as from various national sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org for a full list of funding institutions).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2012. World Health Organization. Strategy and action plan for healthy ageing in Europe, 2012–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt M, Deindl C, Hank K. Tracing the origins of successful aging: the role of childhood conditions and social inequality in explaining later life health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niedzwiedz CL, Katikireddi SV, Pell JP, Mitchell R. Life course socio-economic position and quality of life in adulthood: a systematic review of life course models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:628. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartley M, Blane D, Montgomery S. Health and the life course: why safety nets matter. BMJ. 1997;314:1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7088.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theou O, Brothers TD, Rockwood MR, Haardt D, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Exploring the relationship between national economic indicators and relative fitness and frailty in middle-aged and older Europeans. Age Ageing. 2013;42:614–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eikemo TA, Bambra C. The welfare state: a glossary for public health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:3–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bambra C. Going beyond The three worlds of welfare capitalism: regime theory and public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:1098–102. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrera M. The ‘Southern Model’ of Welfare in Social Europe. J Eur Soc Pol. 1996;6:17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esping-Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aspalter C, Jinsoo K, Sojeung P. Analysing the welfare state in Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovenia: an ideal-typical perspective. Soc Pol Adm. 2009;43:170–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bambra C. Health inequalities and welfare state regimes: theoretical insights on a public health ‘puzzle. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:740–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.2011.136333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging. 2011. SHARE Release Guide 2.5.0 Waves 1 & 2: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging.

- 13.Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C, et al. Data resource profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:992–1001. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diener E, Inglehart R, Tay L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc Indicator Res. 2012;112:497–527. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichhorn J. Happiness for believers? Contextualizing the effects of religiosity on life-satisfaction. Eur Sociol Rev. 2012;28:583–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pittau MG, Zelli R, Gelman A. Economic disparities and life satisfaction in European regions. Soc Indicator Res. 2010;96:339–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNESCO. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization ISCED 1997 Mappings. 2012. Available at http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/ISCEDMappings/Pages/default.aspx. 24 June 2013, date last accessed.

- 18.SHARE. Share w2 Questionnaire version 2.7 2006-09-21. 2006. Available at: http://www.share-project.org/data-access-documentation/questionnaires/questionnaire-wave-2.html. (4 March 2013, date last accessed)

- 19.Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. International variation in the size of mortality differences associated with occupational status. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:742–50. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.4.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh-Manoux A, Gourmelen J, Ferrie J, Silventoinen K, Guéguen A, Stringhini S, et al. Trends in the association between height and socioeconomic indicators in France, 1970–2003. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mein G, Johal S, Grant R, Seale C, Ashcroft R, Tinker A. Predictors of two forms of attrition in a longitudinal health study involving ageing participants: an analysis based on the Whitehall II study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra SI, Dooley D, Catalano R, Serxner S. Telephone health surveys: potential bias from noncompletion. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:94–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tolonen H, Helakorpi S, Talala K, Helasoja V, Martelin T, Prättälä R. 25-year trends and socio-demographic differences in response rates: Finnish Adult Health Behaviour Survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:409–15. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borrell C, Espelt A, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Burstrom B, Muntaner C, Pasarin MI, et al. Analyzing differences in the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in self-perceived health by countries of different political tradition in Europe. Int J Health Serv. 2009;39:321–41. doi: 10.2190/HS.39.2.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunst AE, Bos V, Lahelma E, Bartley M, Lissau I, Regidor E, et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in self-assessed health in 10 European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:295–305. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eikemo TA, Huisman M, Bambra C, Kunst AE. Health inequalities according to educational level in different welfare regimes: a comparison of 23 European countries. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30:565–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richter M, Rathman K, Gabhainn SN, Zambon A, Boyce W, Hurrelmann K. Welfare state regimes, health and health inequalities in adolescence: a multilevel study in 32 countries. Sociol Health Illn. 2012;34:858–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKee M, Stuckler D. Older people in the UK: under attack from all directions. Age Ageing. 2013;42:11–3. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.