Abstract

Objective:

To determine the magnitude of potentially causal relationships among vascular risk factors (VRFs), large-artery atheromatous disease (LAD), and cerebral white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in 2 prospective cohorts.

Methods:

We assessed VRFs (history and measured variables), LAD (in carotid, coronary, and leg arteries), and WMH (on structural MRI, visual scores and volume) in: (a) community-dwelling older subjects of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936, and (b) patients with recent nondisabling stroke. We analyzed correlations, developed structural equation models, and performed mediation analysis to test interrelationships among VRFs, LAD, and WMH.

Results:

In subjects of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (n = 881, mean age 72.5 years [SD ±0.7 years], 49% with hypertension, 33% with moderate/severe WMH), VRFs explained 70% of the LAD variance but only 1.4% to 2% of WMH variance, of which hypertension explained the most. In stroke patients (n = 257, mean age 74 years [SD ±11.6 years], 61% hypertensive, 43% moderate/severe WMH), VRFs explained only 0.1% of WMH variance. There was no direct association between LAD and WMH in either sample. The results were the same for all WMH measures used.

Conclusions:

The small effect of VRFs and LAD on WMH suggests that WMH have a large “nonvascular,” nonatheromatous etiology. VRF modification, although important, may be limited in preventing WMH and their stroke and dementia consequences. Investigation of, and interventions against, other suspected small-vessel disease mechanisms should be addressed.

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are a major component of cerebral small-vessel disease (SVD) and substantially increase the risk of dementia, stroke,1 and physical disability.2 Despite this considerable clinical and societal impact, the causes of SVD and WMH are poorly understood.3

WMH are associated with several common vascular risk factors (VRFs) offering potentially modifiable targets: hypertension,4–9 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and possibly carotid stenosis.10 Hypertension was associated with WMH progression6–9; better blood pressure (BP) control delayed WMH progression in observational studies9 and in one randomized controlled trial (RCT).11 However, there are anomalies: in larger RCTs, antihypertensive treatment did not prevent WMH progression,12 intensive BP reduction did not prevent recurrent lacunar stroke,13 and the associations between BP and WMH were often weak14 or disappeared with correction for age and baseline WMH, both strong predictors of WMH progression.15–17 Statins did not prevent WMH progression,18 and dual (vs mono) antiplatelet therapy increased death in patients with lacunar stroke without preventing recurrence.19,20

These discrepancies question the strength of associations among VRFs, atheroma, and SVD, contrasting with the effectiveness of antihypertensive, antiplatelet drugs and statins in preventing atheromatous ischemic stroke. We hypothesized that if WMH mainly occur secondary to VRFs or are a “small-vessel” form of atheroma, then either of these or both should explain most WMH variance. We determined how much WMH variability was attributable to VRFs and/or large-artery atheromatous disease (LAD) in 2 cohorts.

METHODS

The derivation cohort is the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (LBC1936),21 community-dwelling older subjects born in 1936, now being studied to determine lifetime influences on aging. The replication cohort is a prospective study of patients with recent nondisabling ischemic stroke, the Mild Stroke Study (MSS).22

The LBC1936 subjects were aged 71 to 74 years (mean 72.5, SD 0.72) at assessment. The MSS patients were aged 34 to 95 years (mean 74, SD 11.62). In both groups, we obtained medical history, physiologic measurements, blood samples, brain MRI, and carotid Doppler ultrasound imaging (full details in references 21–23).

We recorded hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia (all medically diagnosed and/or on relevant drugs), ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease or other circulatory problems (all diagnosed by general practitioner or hospital doctor), and smoking (current vs stopped >1 year ago or never smoked). History of stroke was also collected in the LBC1936 cohort. All MSS participants had an index stroke (on clinical criteria and MRI with diffusion imaging22) as a study entry criterion.

In the LBC1936 cohort, we measured systolic and diastolic BP, each 3 times sitting and standing during a 4-hour Clinical Research Facility assessment. We also measured the following: ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI), carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) in the common carotid artery and carotid bulb on both sides (mean of 3 measures by Framingham24 and by manual caliper measurements), carotid flow velocities, maximum stenosis affecting the internal carotid artery/bulb/common carotid artery,25 hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), plasma total cholesterol and albumin, urinary albumin, microalbuminuria, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). All measures were performed blinded to all other data. In the MSS subjects, we also performed echocardiography where clinically indicated and measured all of the above (including carotid Doppler ultrasound on the same scanner with the same operators) except ABPI, HbA1c, IMT, eGFR, microalbuminuria, and albumin, and only one BP reading was available, but we had more detailed history and medical examination.

All LBC1936 and MSS subjects underwent brain MRI on the same 1.5-tesla GE Signa Horizon HDx clinical scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) and had T1-, T2-, and T2*-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial whole-brain imaging.22,23 A neuroradiologist, trained in WMH rating, quantified the WMH on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery using the Fazekas score.26 A second neuroradiologist cross-checked a random 20% of ratings, uncertain ratings, and cases with suspected infarct. In the LBC1936, we also measured WMH volumes in cubic millimeters using a validated multispectral image processing method (http://sourceforge.net/projects/bric1936/) that maps combinations of magnetic resonance sequences to the red-green color space for tissue segmentation.23,27 We checked all segmented images visually for accuracy blinded to all clinical details, manually removed any errors, and masked all imaging-detected infarcts to avoid confounding the WMH volumes.28

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Both studies were approved by Lothian Research Ethics (LBC1936 REC 07/MRE00/58; MSS 2002/8/64) and LBC1936 additionally by the Scottish Multicentre (MREC/01/0/56) Research Ethics. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Analytical approach.

We used all available data, because the pattern of missing values was acceptably random (e.g., more LBC1936 subjects completed carotid than brain imaging). WMH were not associated with carotid disease on right or left sides separately so we combined sides. We used the average of sitting BPs after exploring multiple individual measures of systolic and diastolic and mean BPs at sitting and standing positions. We examined correlation matrices and excluded variables with no/low correlation from further analysis, e.g., eGFR and microalbuminuria. Where both variables were continuous, we used the Pearson correlation coefficient; dichotomous, we used tetrachoric correlation; and 1 dichotomous/1 continuous, we used biserial correlation. The p values for the latter 2 correlations were determined from their variance and standard error.29

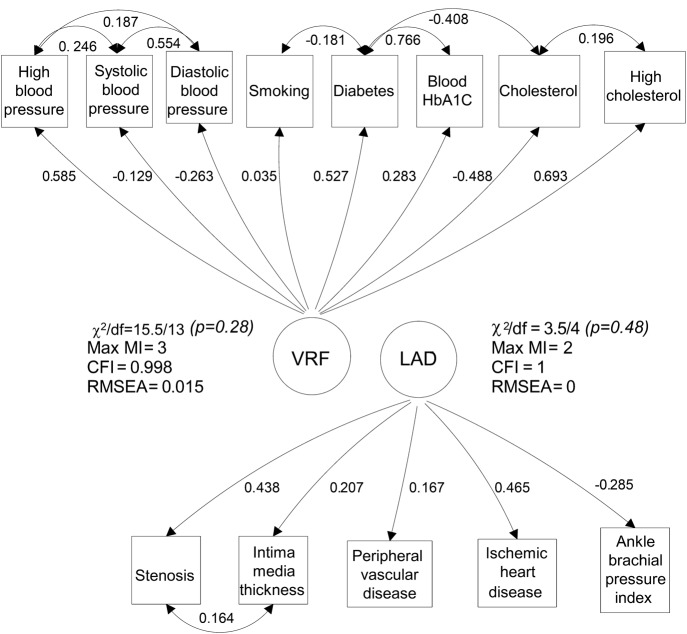

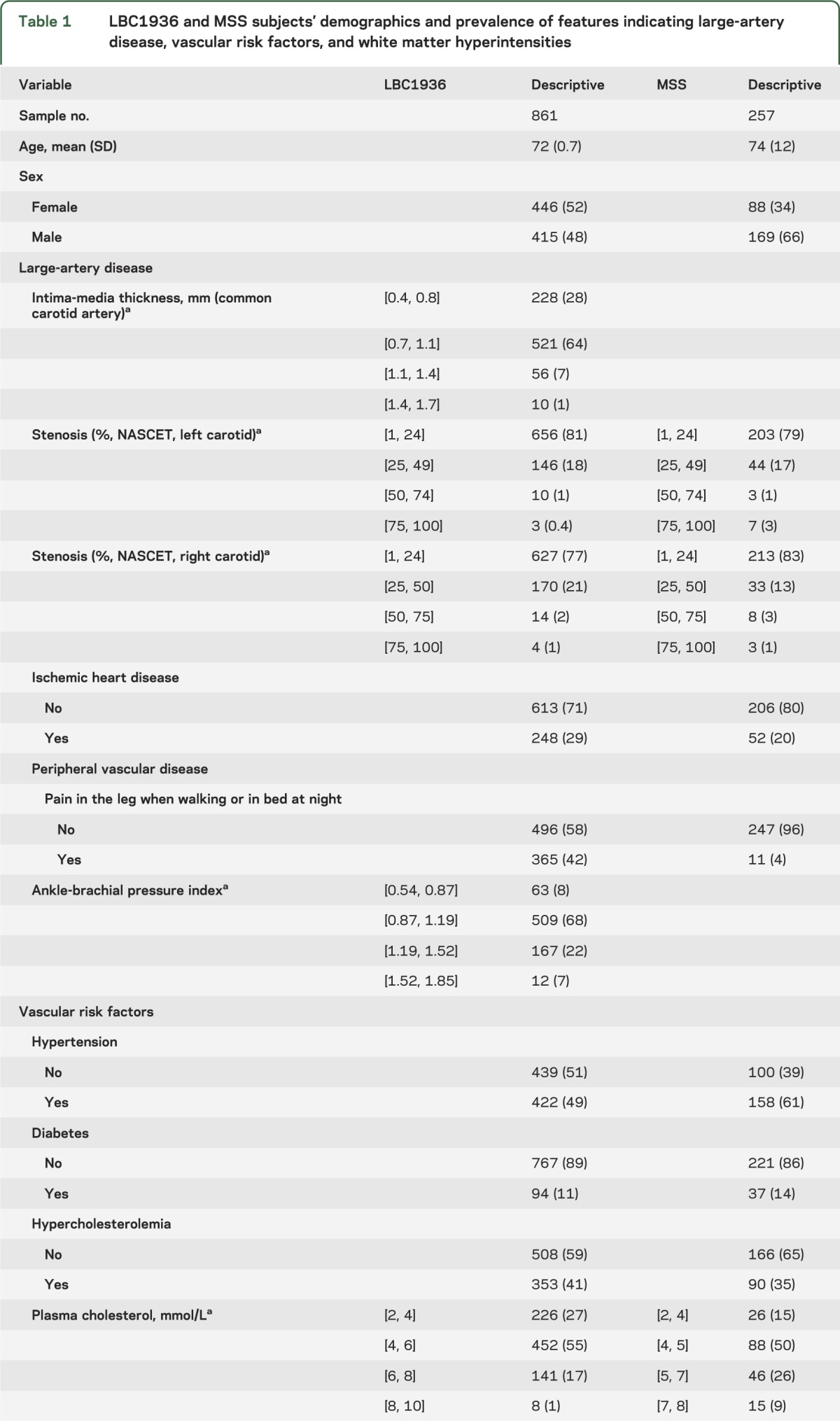

We used structural equation models to test the contribution of VRFs and LAD to the WMH burden. Such models are described using path diagrams, e.g., figures 1 and 2, where the square boxes represent measured observations, e.g., BP. Each circle represents a “latent construct,” e.g., LAD or VRFs, that underlies a combination of correlated individual measured variables. Single-headed arrows represent simple regression relationships, and double-headed arrows represent correlations. In structural equation models, it is conventional to divide the modeling into 2 parts. Measurement models are used to check whether the variance shared by several measured variables constitutes an underlying latent trait. Structural models are used to test hypothesized relationships among latent and measured variables. Figure 1 shows measurement models for LAD and VRFs, where each circle represents an underlying latent construct that is a weighted combination of the correlated measured variables. Figure 2 shows structural models of relationships between these latent constructs of LAD, VRFs, and WMH. The models shown in figure 2, A and B, test the hypothesis that the association between LAD and WMH may be explained by common association with VRFs. Under this hypothesis, we expected the total association between LAD and WMH (figure 2A) to be reduced when VRFs were controlled in both variables (figure 2B). The models shown in figure 2, C and D, test the hypothesis that any direct relationship between VRFs and WMH (figure 2C) is mediated by LAD (figure 2D; details in appendix e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org).

Figure 1. LBC1936 cohort: Diagram of measurement models for the VRF and LAD constructs.

Standardized loadings and residual correlations are shown. Numbers adjacent to paths may be squared to obtain the shared variance between adjacent variables. Double-headed arrows are correlations; single-headed arrows are hypothesized causal pathways. The convention used represents manifest (measured) variables as rectangles and constructed variables (VRFs or LAD) as circles. Model fit parameters are shown adjacent to the constructed variable: a nonsignificant χ2 is a sign of a well-fitting model; the Max MI (which indicates the degree of greatest local strain within the model in terms of a potential reduction in model χ2); the CFI (≥0.90 indicates acceptable fit); and the RMSEA (<0.06 indicates acceptable fit). CFI = comparative fit index; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; LAD = large-artery atheromatous disease; LBC1936 = Lothian Birth Cohort 1936; Max MI = maximum modification index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; VRF = vascular risk factor.

Figure 2. Structural models in the LBC1936.

(A) This model is the total association between LAD and WMH. (B) Hierarchical association with VRFs controlled. (C) Total effect of VRFs on WMH. (D) The mediation model (see the text). Standardized regression coefficients (parameter weights) are shown adjacent to each path. Each arrow is directed from a predictor variable to the outcome variable. In model B, the 0.828 indicates that approximately 70% of the variance in LAD is explained by VRFs and the 0.111 indicates that approximately 2% of the variance in WMH is explained by VRFs. The 0.292 and 0.984 adjacent to the lateral arrows in model B indicate the variance that is unexplained by VRFs on LAD and WMH, respectively. The estimates shown in the figure are for WMH measured using combined periventricular and deep Fazekas scores. The estimates for the model using other WMH measures are shown in table 2. R2 is the WMH model R2 value; s2 is the residual variance. LAD = large-artery atheromatous disease; LBC1936 = Lothian Birth Cohort 1936; VRF = vascular risk factor; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

In the LBC1936, we grouped the measured variables into those that represented (1) VRFs, (2) LAD in the arteries supplying the brain, heart, or legs, and (3) WMH measures. VRFs included history variables (hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, smoking) and measured variables (BP, HBA1c, and plasma cholesterol). LAD included history variables (ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, other circulatory problems) and measured variables (ABPI, carotid stenosis, and IMT; figure 1).24 The variables were grouped based on medical knowledge, correlations, a scree plot of the principal components, and the exploratory factor analysis.30 For WMH, because deep and periventricular WMH were highly correlated (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), we combined them into a summed Fazekas score. We also tested WMH volume as a percent of intracranial volume and of brain parenchymal volume. The correlation between the 2 percentage WMH scores was 0.998, and between the Fazekas scores and each of the 2 percentage scores was 0.760 and 0.765. The Fazekas score was ordinal, and both percentage measures were continuous variables. Both were positively skewed and zero-inflated (less than 18% of the sample were zeros), and these measures were treated as censored from below at zero using Tobit regression.

We performed a similar analysis in the MSS cohort by testing groupings of VRF and LAD measured variables and WMH (figure e-1).

We used Mplus version 6.131 to fit the measurement and structural models of regression relationships between the variables simultaneously. We estimated model parameters by weighted least-squares and assessed the indirect effect in the mediation model (model D) using a bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval derived by Monte Carlo sampling.32,33 We controlled for sex in all variables but not age (adjusting for age had negligible effect and all subjects were of very similar ages, SD = 0.71 years). We examined estimates of factor loadings (unstandardized, standardized, and squared multiple correlation coefficient) and several indices of model fit: the comparative fit index (≥0.90 indicates acceptable fit), the root mean square error of approximation (<0.06 indicates acceptable fit), and the maximum modification index (indicates the degree of greatest local strain within the model in terms of a potential reduction in model χ2).

RESULTS

Primary analysis.

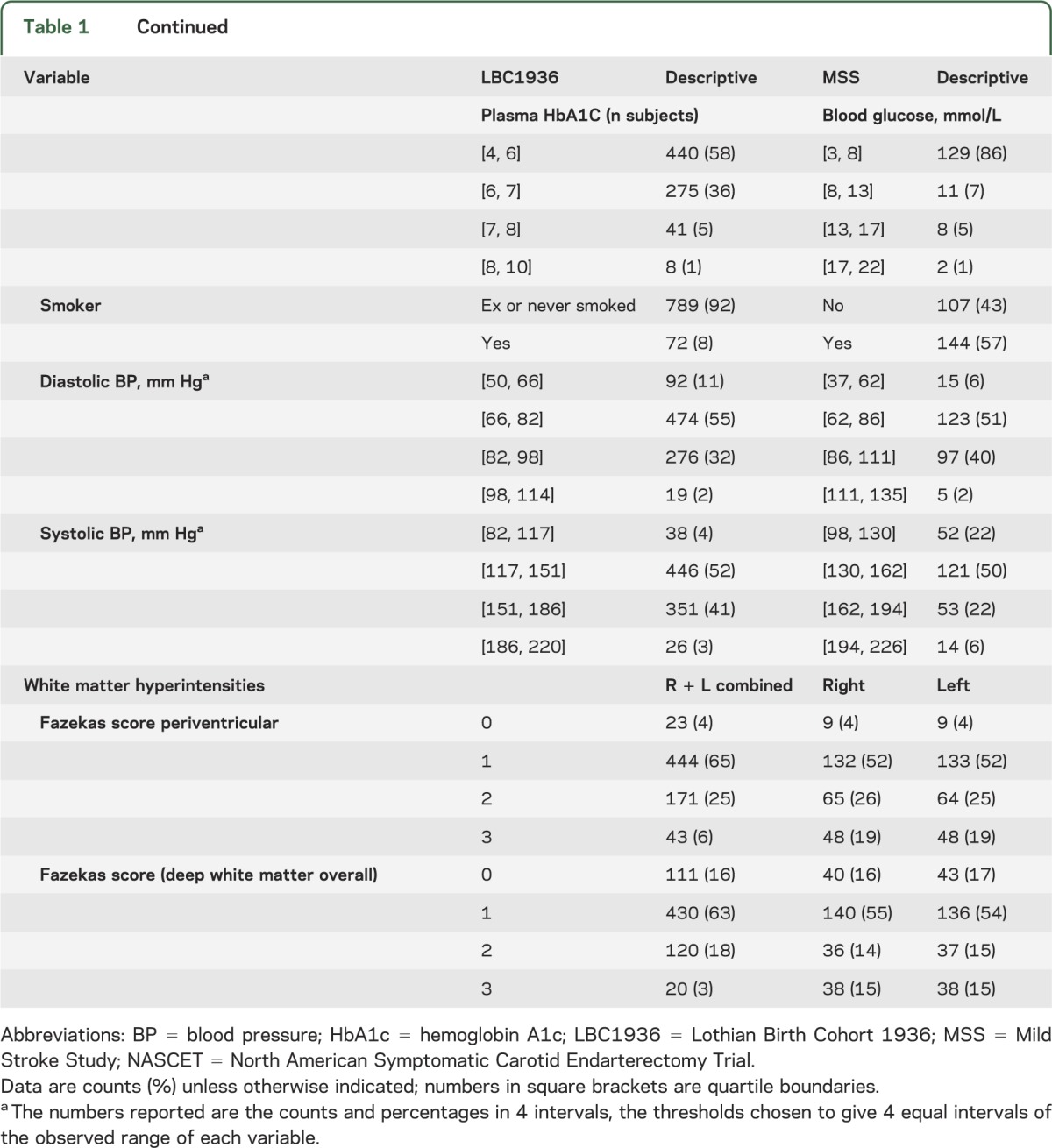

In the LBC1936, 861 subjects (415, 48% male) of mean age 72.5 years (SD 0.7, range 71–74 years) had full clinical assessment and carotid imaging; 681 subjects completed brain imaging and provided WMH scores and volumes. Of the 861, 422 (49%) had hypertension, 94 (11%) had diabetes, 248 (29%) had ischemic heart disease, the median carotid stenosis was 20%, and 33% had moderate or severe WMH scores (table 1).

Table 1.

LBC1936 and MSS subjects' demographics and prevalence of features indicating large-artery disease, vascular risk factors, and white matter hyperintensities

Multivariate measurement models to derive the VRF and LAD latent variables (figure 1) indicate that all observed variables contributed significantly to the latent variable (p < 0.05) except for smoking (p = 0.66), which nonetheless we included in the VRF model. The models all fitted the data well (figure 1).

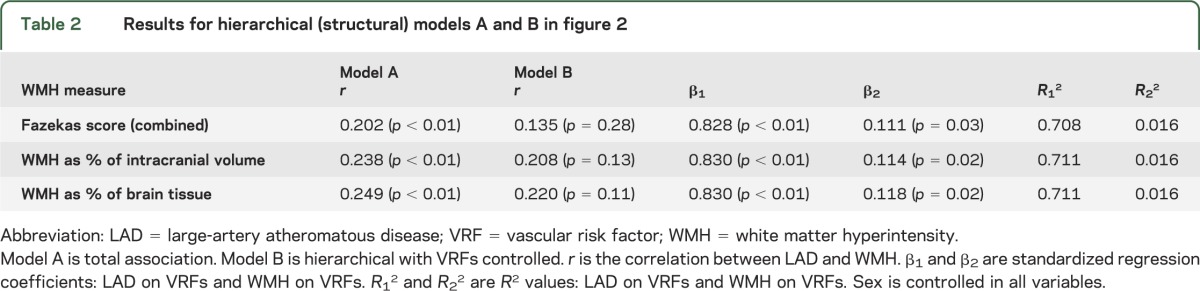

Structural models (figure 2) show the standardized estimates for WMH measured using Fazekas scores. Without accounting for VRFs (figure 2A), there was a small but reliable shared variance of approximately 4% and 6% between LAD and WMH, depending on which WMH measure was used (all 3 WMH measures were statistically significant; table 2).

Table 2.

Results for hierarchical (structural) models A and B in figure 2

However, when VRFs were accounted for (figure 2B), the total association between LAD and WMH became smaller and nonsignificant with all 3 WMH measures (table 2). Therefore, the small association between LAD and WMH seen in model A before VRFs were considered was mainly explained by VRFs acting through LAD. In addition, VRFs were a far stronger predictor of LAD than of WMH, accounting for approximately 70% of variation in LAD burden (standardized parameter weight 0.828) but less than 2% of variation in WMH (standardized parameter weight 0.111).

The mediation model (figure 2, C and D) indicates that the standardized total effect of VRFs (figure 2C, effect c in table e-1), explained no more than a small (2%) but significant variance in WMH. Exploring the effect of LAD as a mediating variable for VRFs (figure 2D, appendix e-1, and table 1) did not explain the missing variance in WMH, instead emphasizing the presence of large influences on WMH that are not captured in history or concurrent measures of VRFs or LAD.

The magnitude of individual VRF contributions to WMH (table e-2, a and b) were all small; e.g., the largest individual contributions to WMH variance were hypertension (2.4%) and smoking (0.89%).

Replication in the stroke cohort.

The MSS patients (n = 257) had similar mean age although a wider range (74.2, SD ±11.6 years, range 34–95 years) than the LBC1936, but more MSS patients were hypertensive (61%), smoked (57.4%), and had moderate to severe WMH scores (44.3% periventricular, 29.6% deep; table 1, figure e-1). A combined hierarchical factor analysis model showed that VRFs explained 35% of LAD variance (standardized parameter weight 0.594) but only 0.1% of WMH variance (standardized parameter weight −0.033), with hypertension again being the strongest individual factor.

DISCUSSION

WMH are a huge health problem, doubling the risk of dementia and trebling the risk of stroke. We were surprised to find that although VRFs explained 70% of the burden of LAD and hypertension was the strongest single risk factor for WMH, all common VRFs combined failed to account for 98% of WMH. Furthermore, there was no direct association between LAD and WMH; any apparent association was through a coassociation with VRFs. We found the same results in 2 separate cohorts, one community-dwelling, the other with stroke, regardless of how WMH were assessed. The mediation model highlighted the absence of key factors to account for most of the WMH variance.

The proportion of subjects with hypertension in the LBC1936 (49%) was similar to the proportion in other similar aging studies,34 and the proportion MSS patients (61%) was similar to stroke patients elsewhere (55%–66%).34 Hypertension was the strongest risk factor for WMH in LBC1936, as in other observational studies.6–9 Consistent with our results, large increments in diastolic BP (e.g., 10 mm Hg above the mean baseline diastolic BP of 83 ± 11 mm Hg) were associated with small differences in WMH in cross-sectional studies (e.g., 1.21% larger WMH volume)4; large increments in systolic BP (20 mm Hg) were associated with small increases in WMH volume (2.5 mL) at follow-up.8 The association between WMH and hypertension applied only to diastolic5 or systolic BP,8 indicating variation in strength of association.35 Most studies adjusted for age, but not for baseline WMH, a strong predictor of WMH progression,16,36 although baseline adjustment should be handled cautiously because it may distort estimates of change in longitudinal studies.37 Others also noted a lack of independent association between WMH and BP in patients with stroke.15

The modest VRF effect is supported by RCTs. Antihypertensive treatment had no effect in the large PRoFESS (Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes) MRI substudy (n = 771) after an average of 28 months12: insufficient BP lowering was blamed for not preventing WMH progression, but the average systolic/diastolic BP reduction in PRoFESS (3.0/1.3 mm Hg) was identical to the systolic/diastolic BP increment (3.0/2.0 mm Hg) blamed for WMH progression over only 14 months of follow-up in a 584-patient observational cohort.14 Intensive vs usual antihypertensive treatment did not significantly reduce recurrent lacunar stroke.13 In RCTs of other VRF modifications that reduce adverse outcomes from LAD, statins had no effect in preventing WMH progression,18 and dual vs mono antiplatelet therapy caused excess hemorrhage and death without reducing recurrent stroke in patients with lacunar stroke.19,20 However, data on lipids and WMH are lacking and should be addressed in further studies.

Our study strengths include the large sample (total n = 1,118), a development (n = 861) and replication (n = 257) cohort, and robust statistics. The narrow age range of the LBC1936 subjects minimized the powerful confounding effect of age on WMH, LAD, and VRFs. The results were the same in the MSS patients whose ages spanned 6 decades and had more vascular disease. The LBC1936 subjects are all white Caucasian, minimizing any influence of ethnic differences on VRFs. We have no reason to think that our subjects are unrepresentative of other Caucasian cohorts (Scotland has one of the highest vascular disease rates in the world). A third of the LBC1936 and approximately 40% of MSS patients had moderate to severe WMH. We found the same results for WMH assessed by visual rating and volume. We carefully excluded infarcts from the WMH volume: inadvertent inclusion of infarcts in “WMH volume” may have inflated associations among VRFs, LAD, and WMH previously.28

The study had limitations. We lacked continuous BP monitoring but used the average of 3 systolic and diastolic BP readings obtained over 4 hours at sitting positions by trained technicians. Most other studies of WMH and BP have not used continuous BP measures. Perhaps our subjects were too old: BP decreases between middle and old age38; WMH may be more closely associated with long-standing elevated BP from middle age.5 However, BP measured 3 years earlier at approximately age 69 was very similar; our “history of hypertension” captured prior hypertension and was the strongest risk factor. Age 72 is not particularly “old.” The stroke cohort including much younger subjects produced the same result. Future studies could test other BP parameters. Adding other imaging markers of SVD might increase the sensitivity for detecting causal relationships. Some variables were missing but without evidence of bias and we used all available data. The high prevalence of peripheral vascular disease in the LBC1936 may represent overreporting but is counterbalanced by the objective measure of peripheral vascular disease with the ABPI and by the MSS where history and examination were very detailed and the same associations were found.

Our results suggest that WMH have a large “nonvascular” component. The remaining unexplained 98% of WMH variance will hinder advances in prevention of dementia, stroke,1 and physical dependency2 in aging. Treating hypertension and diabetes, lowering cholesterol, and stopping smoking are important. Lifestyles that minimize vascular risk should be encouraged. Other modifiable risk factors (e.g., vitamins),39 dietary factors (e.g., salt), inflammation, and other nonvascular contributing mechanisms should be sought.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the radiographers at the Brain Research Imaging Centre; Elizabeth Eadie and Avril Thomas, ultrasonographers at the Department of Neuroradiology, Edinburgh (www.bric.ed.ac.uk); the nurses of the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Edinburgh (www.wtcrf.ed.ac.uk); P. Davies, J. Corley, A. Pattie, and R. Henderson for coordination, data collection, and entry for LBC1936; and the staff at Lothian Health Board and at the SCRE Centre, University of Glasgow.

GLOSSARY

- ABPI

ankle-brachial pressure index

- BP

blood pressure

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- IMT

intima-media thickness

- LAD

large-artery atheromatous disease

- LBC1936

Lothian Birth Cohort 1936

- MSS

Mild Stroke Study

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SVD

small-vessel disease

- VRF

vascular risk factor

- WMH

white matter hyperintensity

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M. Wardlaw, M. Allerhand, I. Deary, F. Doubal: study concept and design. F. Doubal, A. Gow, I. Deary, J. Starr, M. Bastin, M. Dennis, J.M. Wardlaw: acquisition of data. M. Allerhand, M. Valdez Hernandez, Z. Morris, F. Doubal, M. Dennis, I. Deary, J. Starr, J.M. Wardlaw: analysis and interpretation. I. Deary, M. Dennis, F. Doubal, M. Allerhand, M. Valdez Hernandez, A. Gow, J.M. Wardlaw: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.M. Wardlaw, I. Deary: study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

The initial recruitment and testing of the LBC1936 was supported by Research Into Ageing: the subsequent imaging and related data collection used here was supported by Age UK (The Disconnected Mind project; the Sidney de Haan Award for Vascular Dementia) and the Medical Research Council (G1001245 and 82800). The MSS was funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive (CZB/4/281) and the Wellcome Trust (075611). The Brain Research Imaging Centre is supported by the SINAPSE Collaboration (www.sinapse.ac.uk) funded by the Scottish Funding Council and Chief Scientist Office and NHS Lothian Research and Development Office. The work was partly undertaken within the University of Edinburgh Centre for Cognitive Aging and Cognitive Epidemiology (G0700704/84698, http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk/), part of the cross council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Initiative. Funding from the BBSRC, EPSRC, ESRC, and MRC is gratefully acknowledged. The study funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baezner H, Blahak C, Poggesi A, et al. Association of gait and balance disorders with age-related white matter changes: the LADIS study. Neurology 2008;70:935–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:483–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus J, Gardener H, Rundek T, et al. Baseline and longitudinal increases in diastolic blood pressure are associated with greater white matter hyperintensity volume: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke 2011;42:2639–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo X, Pantoni L, Simoni M, et al. Blood pressure components and changes in relation to white matter lesions: a 32-year prospective population study. Hypertension 2009;54:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dufouil C, De Kersaint-Gilly A, Besancon V, et al. Longitudinal study of blood pressure and white matter hyperintensities: the EVA MRI Cohort. Neurology 2001;56:921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Oudkerk M, et al. Hypertension and cerebral white matter lesions in a prospective cohort study. Brain 2002;125:765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottesman RF, Coresh J, Catellier DJ, et al. Blood pressure and white-matter disease progression in a biethnic cohort. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Stroke 2010;41:3–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godin O, Tzourio C, Maillard P, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C. Antihypertensive treatment and change in blood pressure are associated with the progression of white matter lesion volumes: the Three-City (3C)-Dijon Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Circulation 2011;123:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Bots ML, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis and cerebral white matter lesions in a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol 2000;247:291–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dufouil C, Chalmers J, Coskun O, et al. Effects of blood pressure lowering on cerebral white matter hyperintensities in patients with stroke: the PROGRESS (Perindopril Protection against Recurrent Stroke Study) Magnetic Resonance Imaging Substudy. Circulation 2005;112:1644–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber R, Weimar C, Blatchford J, et al. Telmisartan on top of antihypertensive treatment does not prevent progression of cerebral white matter lesions in the prevention regimen for effectively avoiding second strokes (PRoFESS) MRI substudy. Stroke 2012;43:2336–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benavente OR, McClure LA, Coffey CS, et al. The secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes (SPS3) Trial: results of the blood pressure intervention. Lancet 2013;382:507–51523726159 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Liu R, Sun W, et al. Different impacts of blood pressure variability on the progression of cerebral microbleeds and white matter lesions. Stroke 2012;43:2916–2922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rost NS, Rahman R, Sonni S, et al. Determinants of white matter hyperintensity volume in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;19:230–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouw AA, van der Flier WM, Fazekas F, et al. Progression of white matter hyperintensities and incidence of new lacunes over a 3-year period: the Leukoaraiosis and Disability Study. Stroke 2008;39:1414–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardlaw JM, Doubal FN, Valdes-Hernandez MC, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability and long term clinical and imaging outcomes in cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke 2013;44:525–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ten Dam VH, van den Heuvel DM, van Buchem MA, et al. Effect of pravastatin on cerebral infarcts and white matter lesions. Neurology 2005;64:1807–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SPS3 Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 2012;367:817–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palacio S, Hart RG, Pearce LA, Benavente OR. Effect of addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on mortality: systematic review of randomized trials. Stroke 2012;43:2157–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deary IJ, Gow AJ, Taylor MD, et al. The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936: a study to examine influences on cognitive ageing from age 11 to age 70 and beyond. BMC Geriatr 2007;7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doubal FN, MacGillivray TJ, Hokke PE, Dhillon B, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Differences in retinal vessels support a distinct vasculopathy causing lacunar stroke. Neurology 2009;72:1773–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wardlaw JM, Bastin ME, Valdes Hernandez MC, et al. Brain aging, cognition in youth and old age and vascular disease in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936: rationale, design and methodology of the imaging protocol. Int J Stroke 2011;6:547–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2007;115:459–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardlaw JM, Lewis S. Carotid stenosis measurement on colour Doppler ultrasound: agreement of ECST, NASCET and CCA methods applied to ultrasound with intra-arterial angiographic stenosis measurement. Eur J Radiol 2005;56:205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:351–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdes Hernandez MC, Ferguson KJ, Chappell FM, Wardlaw JM. New multispectral MRI data fusion technique for white matter lesion segmentation: method and comparison with thresholding in FLAIR images. Eur Radiol 2010;20:1684–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Valdes Hernandez MC, Doubal F, Chappell FM, Wardlaw JM. How much do focal infarcts distort white matter lesions and global cerebral atrophy measures? Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;34:336–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox J, Weisberg S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 2nd ed Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Child D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd ed London: Continuum International Publishing Group; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide, 6th ed Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004;36:717–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008;40:879–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE Study): a case-control study. Lancet 2010;376:112–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Dijk EJ, Breteler MMB, Schmidt R, et al. The association between blood pressure, hypertension, and cerebral white matter lesions: Cardiovascular Determinants of Dementia Study. Hypertension 2004;44:625–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Vrooman HA, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Progression of cerebral small vessel disease in relation to risk factors and cognitive consequences: Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke 2008;39:2712–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wills AK, Lawlor DA, Matthews FE, et al. Life course trajectories of systolic blood pressure using longitudinal data from eight UK cohorts. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cavalieri M, Schmidt R, Chen C, et al. B vitamins and magnetic resonance imaging–detected ischemic brain lesions in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke: the VITAmins TO Prevent Stroke (VITATOPS) MRI-substudy. Stroke 2012;43:3266–3270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.