Abstract

Objective:

To determine the contribution of TUBB4A, recently associated with DYT4 dystonia in a pedigree with “whispering dysphonia” from Norfolk, United Kingdom, to the etiopathogenesis of primary dystonia.

Methods:

High-resolution melting and Sanger sequencing were used to inspect the entire coding region of TUBB4A in 575 subjects with primary laryngeal, segmental, or generalized dystonia.

Results:

No pathogenic variants, including the exon 1 variant (c.4C>G) identified in the DYT4 whispering dysphonia kindred, were found in this study.

Conclusion:

The c.4C>G DYT4 mutation appears to be private, and clinical testing for TUBB4A mutations is not justified in spasmodic dysphonia or other forms of primary dystonia. Moreover, given its allelic association with leukoencephalopathy hypomyelination with atrophy of basal ganglia and cerebellum and protean clinical manifestations (chorea, ataxia, dysarthria, intellectual disability, dysmorphic facial features, and psychiatric disorders), DYT4 should not be categorized as a primary dystonia.

The advent of exome sequencing has expedited the identification of genes linked to dystonia, a genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by involuntary and sustained muscle contractions causing twisting and repetitive movements.1–5 Recently, exome sequencing was combined with linkage analysis to identify an exon 1 mutation in TUBB4A (c.4C>G; p.Arg2Gly) as the cause of DYT4 or “whispering dystonia,” first described by Parker in a family from Heacham in Norfolk, United Kingdom.2,3,6,7 The p.Arg2Gly variant is located within the autoregulatory MREI domain (methionine–arginine–glutamic acid–isoleucine) of β-tubulin 4a. Concurrently, an exon 4 mutation in TUBB4A (c.745 G>A; p.Asp249Asn) was found to cause leukoencephalopathy hypomyelination with atrophy of basal ganglia and cerebellum (H-ABC).8 The phenotypic spectrum of H-ABC includes dystonia, delayed psychomotor development, spasticity, ataxia, dysarthria, short stature, and microcephaly.8 MRI in subjects with H-ABC shows cerebellar and striatal atrophy along with diffuse hypomyelination.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Human studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with formal approval from the institutional review boards at each participating study site. All genetic and phenotypic analyses and publication of the results were approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board (01-07346-XP). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects.

Subjects.

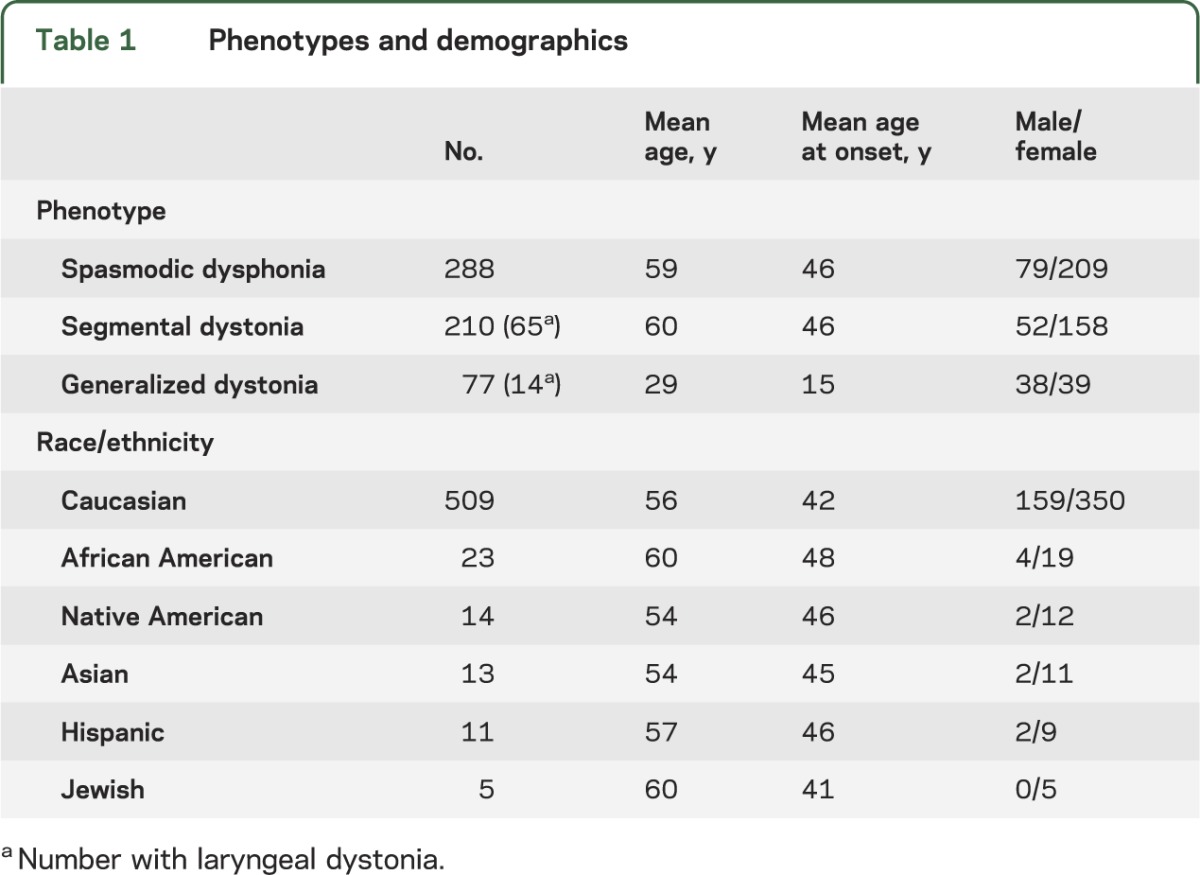

Our primary dystonia cohort included 575 subjects (table 1), mainly non-Hispanic Caucasians of European descent residing in the United States. All subjects with laryngeal dystonia had spasmodic dysphonia. One subject with segmental dystonia had inspiratory laryngeal dystonia. The diagnosis of laryngeal dystonia was made by a board-certified otorhinolaryngologist or a neurologist with subspecialty expertise in movement disorders. Enrollment of patients with primary dystonia has been described previously.4,5 High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral whole blood.

Table 1.

Phenotypes and demographics

Objectives.

To determine the contributions of TUBB4A to primary dystonia, high-resolution melting (HRM)4,5 and Sanger sequencing were used to examine the entire coding region of TUBB4A in 575 subjects with primary laryngeal, segmental, or generalized dystonia (table 1). Mutations in THAP1, GNAL, and exon 5 of TOR1A were excluded in the entire cohort.4,9,10

Screening for TUBB4A variants.

Exons 1 and 4 were examined with Sanger sequencing in the forward and reverse directions,4,5 whereas exons 2 and 3 were screened with HRM (table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). Compared with Sanger sequencing, HRM is a more rapid and less expensive technology for variant detection.11 With small amplicons (<300 base pairs), the sensitivity of heterozygote scanning is nearly 100%, and false positives are readily excluded with Sanger sequencing.11 However, the value of HRM as a variant screening tool is limited in regions that contain common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Sanger sequencing was chosen for exons 1 and 4, and contiguous intronic regions, because these genomic intervals of TUBB4A harbor common SNPs (e.g., reference SNP rs390530, rs61741669, and rs2071347) and the variants associated with DYT4 and H-ABC. HRM was performed with the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system and High Resolution Master Mix (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) in accordance with our laboratory protocol.5 Using 20 ng of DNA template, 1X HRM Master Mix, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 200 nM of each primer in a 10-μL reaction volume, the reactions were performed in either 96- or 384-well plates. Melting curves and difference plots were analyzed by at least 2 investigators blinded to phenotype. For samples with shifted melting curves, PCR products were cleaned using ExoSAP-IT and Sanger sequenced in the forward and reverse directions.

Variant analysis.

In silico mutation prediction programs SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org), and PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) were used to access the pathogenicity of novel and previously reported missense sequence variants. SIFT is a sequence homology–based tool that sorts intolerant from tolerant amino acid substitutions and predicts whether an amino acid substitution at a particular position in a protein will have a phenotypic effect.12 MutationTaster applies a naive Bayes classifier to data derived from evolutionary conversation, splice-site changes, loss of protein features, and changes that might affect the amount of messenger RNA to predict disease potential.13 PolyPhen-2 predicts pathogenicity by applying a probabilistic classifier to sequence- and structure-based information.14 The sensitivities and accuracies of SIFT, MutationTaster, and PolyPhen-2 range from 79% to 89% and 84% to 88%, respectively.13,15

RESULTS

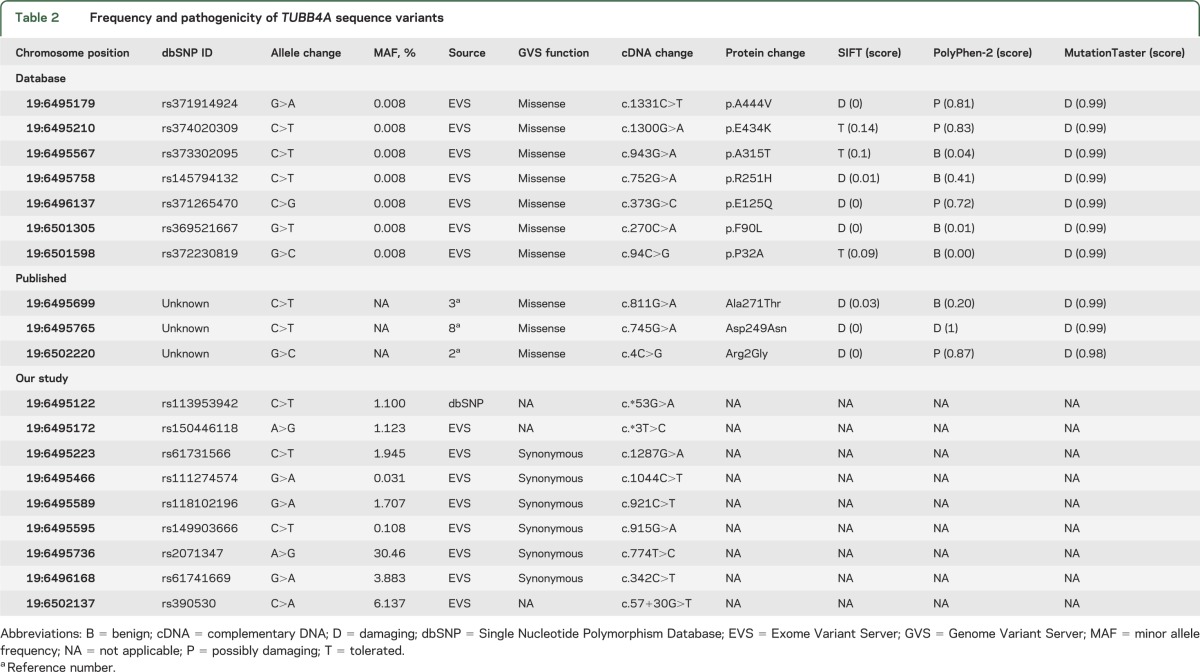

No novel or pathogenic TUBB4A variants were discovered in our cohort. However, previously reported nonpathogenic variants in dbSNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database) and the Exome Variant Server (EVS) of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute were identified (table 2). Among a cohort of 6,503 subjects, EVS reports 7 missense variants in this highly conserved gene (figure e-1). SIFT and MutationTaster suggest that p.Arg2Gly is disease-causing while PolyPhen-2 predicts that this variant is only possibly damaging. Lohmann et al.3 screened 394 unrelated subjects with dystonia and identified a second variant (p.Ala271Thr) in a single subject with segmental craniocervical dystonia. The p.Ala271Thr variant is predicted to be benign by PolyPhen-2 and damaging by MutationTaster and SIFT. Of the 7 variants reported by EVS, 2 are predicted to be pathogenic by MutationTaster and SIFT but benign by PolyPhen-2. The p.Asp249Asn variant associated with H-ABC is predicted to be damaging by all 3 programs.

Table 2.

Frequency and pathogenicity of TUBB4A sequence variants

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that TUBB4A variants do not make a significant contribution to the etiopathogenesis of primary dystonia. Careful analysis of published DYT4 and H-ABC phenotypes indicates the presence of significant phenotypic overlap. H-ABC exhibits an earlier onset and more severe phenotype than DYT4. Therefore, DYT4 may be a “form fruste” of H-ABC. Unlike one or more members of the DYT4 pedigree, none of the subjects in our cohort had a “hobby horse” gait, ataxia, dysmorphic facies, dementia, chorea, or severe dysarthria.6,7 Moreover, the overt improvement in dystonia and/or gait with alcohol, propranolol, or tetrabenazine that has been reported in subjects with DYT4 is not consistent with clinical findings in the vast majority of individuals with primary dystonia.6,7 H-ABC is characterized by defective myelination and atrophy of the striatum and cerebellum.8 Although MRI is reportedly normal in DYT4,7 technical details of imaging and images have not been provided in publications related to the DYT4 pedigree. It is possible that more severely affected older individuals with the p.Arg2Gly variant do show evidence of hypomyelination and atrophy on MRI.

Although there is overt phenotypic overlap between DYT4 and H-ABC, it is possible that these neurogenetic disorders are more discrete at the molecular level. In this regard, there have been numerous studies linking tubulin, a major component of microtubules, to a variety of neurologic conditions ranging from congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles to lissencephaly.16–19 Mutations within the N-terminal MREI domain of β-tubulin 4a, such as p.Arg2Gly, disrupt autoregulation of TUBB4A transcript levels.20 In contrast, the p.Asp249Asn mutation is located within the T7 loop of β-tubulin 4a, which interacts with the guanosine triphosphate nucleotide bound to the N-site of α-tubulin.21 As such, Asn249 β-tubulin 4a could alter microtubule polymerization.

Taken together, these results suggest that (1) p.Arg2Gly is a private mutation, (2) DYT4 should not be classified as a primary dystonia, (3) DYT4 may be a form fruste of H-ABC, and (4) genetic testing for TUBB4A mutations should be limited to pedigrees with H-ABC phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- EVS

Exome Variant Server

- H-ABC

hypomyelination with atrophy of basal ganglia and cerebellum

- HRM

high-resolution melting

- MREI

methionine–arginine–glutamic acid–isoleucine

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.S.L. designed the study. S.R.V., J.X., and M.S.L. performed experiments and analyzed data. R.W.B., D.M., A.B., and M.S.L. examined patients and collected blood specimens. S.R.V. and M.S.L. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by grants to M.S.L. from the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, Tyler's Hope for a Dystonia Cure, NIH (R01 NS069936 and R01 NS082296), and the NIH U54 Dystonia Coalition (1U54NS065701) Pilot Projects Program. The Dystonia Coalition is part of the NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. Funding and/or programmatic support for this project has been provided by NS067501 from the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The views expressed in written materials or publications do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

DISCLOSURE

S. Vemula, J. Xiao, R. Bastian, D. Momčilović, and A. Blitzer report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. M. LeDoux serves on the speakers bureaus for Lundbeck, UCB Pharma, and Teva Neuroscience; serves on the Xenazine Advisory Board for Lundbeck and Azilect Advisory Board for Teva; receives research support from the NIH, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, Tyler's Hope for a Dystonia Cure, Prana, and CHDI; and receives royalty payments for Animal Models of Movement Disorders (Elsevier). Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charlesworth G, Plagnol V, Holmstrom KM, et al. Mutations in ANO3 cause dominant craniocervical dystonia: ion channel implicated in pathogenesis. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:1041–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersheson J, Mencacci NE, Davis M, et al. Mutations in the autoregulatory domain of beta-tubulin 4a cause hereditary dystonia. Ann Neurol 2013;73:546–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohmann K, Wilcox RA, Winkler S, et al. Whispering dysphonia (DYT4 dystonia) is caused by a mutation in the TUBB4 gene. Ann Neurol Epub 2012 Dec 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Vemula SR, Puschmann A, Xiao J, et al. Role of Gα(olf) in familial and sporadic adult-onset primary dystonia. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:2510–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao J, Uitti RJ, Zhao Y, et al. Mutations in CIZ1 cause adult-onset primary cervical dystonia. Ann Neurol 2012;71:458–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker N. Hereditary whispering dysphonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:218–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox RA, Winkler S, Lohmann K, Klein C. Whispering dysphonia in an Australian family (DYT4): a clinical and genetic reappraisal. Mov Disord 2011;26:2404–2408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons C, Wolf NI, McNeil N, et al. A de novo mutation in the β-tubulin gene TUBB4A results in the leukoencephalopathy hypomyelination with atrophy of the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Am J Hum Genet 2013;92:767–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeDoux MS, Xiao J, Rudzinska M, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in THAP1 dystonia: molecular foundations and description of new cases. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:414–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao J, Bastian RW, Perlmutter JS, et al. High-throughput mutational analysis of TOR1A in primary dystonia. BMC Med Genet 2009;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittwer CT. High-resolution DNA melting analysis: advancements and limitations. Hum Mutat 2009;30:857–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res 2001;11:863–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods 2010;7:575–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010;7:248–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnad F, Baucom A, Mukhyala K, Manning G, Zhang Z. Assessment of computational methods for predicting the effects of missense mutations in human cancers. BMC Genomics 2013;14(suppl 3):S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leandro-Garcia LJ, Leskelä S, Landa I, et al. Tumoral and tissue-specific expression of the major human β-tubulin isotypes. Cytoskeleton 2010;67:214–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh KK, Tsai LH. MicroTUB(B3)ules and brain development. Cell 2010;140:30–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tischfield MA, Baris HN, Wu C, et al. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. Cell 2010;140:74–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tischfield MA, Engle EC. Distinct α- and β-tubulin isotypes are required for the positioning, differentiation and survival of neurons: new support for the “multi-tubulin” hypothesis. Biosci Rep 2010;30:319–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen TJ, Machlin PS, Cleveland DW. Autoregulated instability of β-tubulin mRNAs by recognition of the nascent amino terminus of β-tubulin. Nature 1988;334:580–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löwe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. Refined structure of αβ-tubulin at 3.5 Å resolution. J Mol Biol 2001;313:1045–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.