Abstract

Refractory status epilepticus is a potentially life-threatening medical emergency. It requires early diagnosis and treatment. There is a lack of consensus upon its semantic definition of whether it is status epilepticus that continues despite treatment with benzodiazepine and one antiepileptic medication (AED), i.e., Lorazepam + phenytoin. Others regard refractory status epilepticus as failure of benzodiazepine and 2 antiepileptic medications, i.e., Lorazepam + phenytoin + phenobarb. Up to 30% patients in SE fail to respond to two antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and 15% continue to have seizure activity despite use of three drugs. Mechanisms that have made the treatment even more challenging are GABA-R that is internalized during status epilepticus and upregulation of multidrug transporter proteins. All patients of refractory status epilepticus require continuous EEG monitoring. There are three main agents used in the treatment of RSE. These include pentobarbital or thiopental, midazolam and propofol. RSE was shown to result in mortality in 35% cases, 39.13% of patients were left with severe neurological deficits, while another 13% had mild neurological deficits.

Keywords: Midazolam, pentobarb, propofol, refractory status epilepticus, status epilepticus

Introduction

Status epilepticus (SE) has traditionally been defined as more than 30 minutes of continuous seizure activity or two or more sequential seizures without full recovery of consciousness in between for a total of more than 30 minutes.[1] In 1999, Lowenstein et al. proposed a new working definition that lowered the threshold to more than 5 minutes of persistent seizure activity.[2] This definition is more relevant clinically given that majority of self-aborting seizures are brief, lasting less than two minutes and the response to therapy declines as the duration of the seizure increases.

Refractory status epilepticus has lacked a consensus definition; most today regard it as status epilepticus that continues despite treatment with benzodiazepine and one antiepileptic medication (AED), e.g., Lorazepam + phenytoin. Others regard refractory status epilepticus as failure of benzodiazepine and 2 antiepileptic medications, e.g., Lorazepam + phenytoin + phenobarb. The first definition is often referred to as 2 AED failure and the second one is termed the 3 AED failure.

Epidemiology

There are about 150,000 cases of SE reported in US each year resulting in 55,000 deaths. The annual incidence of status epilepticus is 10 to 40/100,000.[3] It is more common in men and African-Americans. The incidence is twice as much in the elderly population and carries a worse prognosis in that cohort.[4] About 25 to 27% patients with epilepsy experience at least one episode of SE.[5] 10 to 12% patients present with SE as the first seizure episode. Most common causes of SE include low AED levels in patients with epilepsy, toxic metabolic encephalopathy, stroke, hypoxic ischemic injury, refractory epilepsy, brain tumor, and meningitis/encephalitis.

The most common complications include respiratory depression, fever, hypotension, infections like pneumonia, bacteremia, and urinary tract infections. SE is associated with a 20% mortality rate.

Up to 30% patients in SE fail to respond to two antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and 15% continue to have seizure activity despite use of three drugs. These people are classified as having refractory status epilepticus (RSE). Non-convulsive seizures and focal seizures at onset have been identified as independent risk factors for RSE. The mortality in RSE is three times that of status epilepticus that is not refractory.

Periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges, bilateral or generalized epileptiform discharges, and electrographic seizures are more commonly seen in patients who had RSE in comparison to those who had responsive SE.

Drug Resistance in status epilepticus

It has been well documented that benzodiazepines are effective in the early phase of status epilepticus but they fail to treat prolonged status epilepticus.[4] This resistance is found in clinical situation and also in animal models of status epilepticus. One important reason for this finding is that there is a change in the GABA receptor; one study has shown that GABA-R are internalized during status epilepticus and thus there is less efficacy of benzodiazepines which act via the GABA receptors.[6]

GABA-mediated synaptic inhibition in a network of cultured hippocampal neurons was diminished after a period of prolonged epileptiform bursting, and that the intracellular accumulation of GABARs was modulated by neuronal activity. The internalization of GABARs was modulated by neuronal activity; recurrent bursting enhanced it, and activity blockade reduced it. Neuronal activity is also known to enhance internalization of AMPA receptors but not NMDA receptors. An increase in the rate of GABAR intracellular accumulation may be one of the mechanisms by which GABA inhibition is reduced during the prolonged seizures of SE.

There is upregulation of multidrug transporter proteins that leads to lowering of levels of AEDs in the brain through its action on blood brain barrier.[7] During status epilepticus, there is upregulation of multidrug resistance protein 2 (Mrp2) expression.

Status epilepticus-induced neuronal death is thought to be initiated by excessive glutamate release, which activates postsynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and triggers receptor-mediated calcium influx, a process called excitotoxicity.[8]

Treatment

There is paucity of scientific evidence to guide treatment of SE, and even less for RSE. The Veterans Administration (VA) Cooperative Study cooperative study from 1998 generated the majority of data used in most SE treatment guidelines.[9]

As in any emergency situation, the first priority should be assessment and management of airway, breathing, and circulation. For SE-specific management, benzodiazepines form the first line of treatment. In addition, continuous EEG monitoring should be initiated to observe the patient for ongoing sub-clinical seizure activity. Other steps that must be undertaken in parallel with the treatment of the seizure activity are the administration of thiamine for the prevention of Wernicke's encephalopathy in a hypoglycemic patient that may be thiamine deficient (such as in the case of chronic alcohol abuse) before administering glucose. A comprehensive metabolic profile, toxin screen, blood gases, and complete blood cell counts should also be evaluated to determine if an underlying, and potentially modifiable cause might be identified.

For SE-specific management, benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment.[10]

Lorazepam is the most commonly used agent, used at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg given in dose of 2 mg/min to a maximum of 8 mg. Lorazepam was shown to be successful in 64.9% patients as the first line compared to 58.2% success with phenobarbital and 55.8 % with Diazepam plus Phenytoin.[9] In out of hospital SE, Lorazepam terminated SE in 59.1%, diazepam in 42.6%, and placebo in 21%.[9] The rate of complications like hypotension, respiratory depression, or cardiac dysrhythmia was 10.6% for Lorazepam, 10.3% for diazepam, and 22.5% for placebo. In outpatients, diazepam suppositories are a preferred agent in management of SE as it can be administered by family members or paramedics while the seizure is occurring. Recently, intranasal midazolam has also become available for these situations.

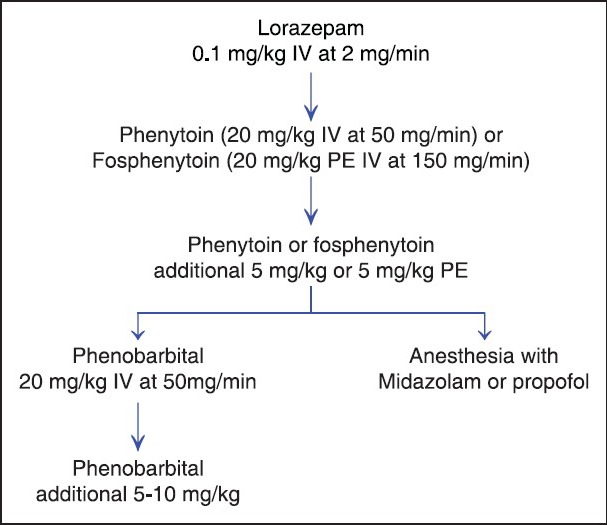

After lorazepam, loading with phenytoin should be initiated with a dose of 20 mg/kg infused at a rate of no greater than 50 mg/min (to avoid hypotension), or the phenytoin pro-drug fosphenytoin dosed in phenytoin equivalents (PEs) at a rate of 150 mg/min, as in Figure 1. An additional dose of phenytoin of 5 mg/kg can be given if seizure activity continues after an additional 20 minutes.

Figure 1.

Creighton status epilepticus protocol

There is controversy about which medication should be employed after failure with phenytoin. However, traditionally if the seizure still fails to abate, the patient is loaded with phenobarbital. Phenobarbital is given as a loading dose of 10 to 20 mg/kg intravenously. Of note, in the VA Cooperative trial, only 5% patients who failed benzodiazepine and phenytoin therapy responded to phenobarbital administration. Therefore, another option would be to go directly to anesthetic agents, i.e., Midazolam or propofol. Before the administration of phenobarb or anesthetic at this stage, patients are electively intubated.

There are three main agents in treatment of RSE. These include pentobarbital or thiopental, midazolam, and propofol.[11] All three have GABA-A agonistic action. Pentobarbital and propofol have NMDA antagonistic and Ca+ channel modulatory effects as well.

Midazolam is one of the first line agents in treatment of RSE. Treatment is initiated with an intravenous loading dose of 0.2 mg/kg followed by an IV infusion initiated at 0.1to 0.4 mg/kg/hr, and titrated to the goal of seizure suppression on EEG. Midazolam is a fast-acting, short half-life benzodiazepine which allows for easy titration. The drug's elimination half-life is approximately 4 to 6 hours. It is metabolized through liver and excreted in urine. The disadvantages include tachyphylaxis after 24 to 48 hours, necessitating ever-increasing doses to maintain seizure control. Also, there is accumulation and so prolonging the time to wakefulness.

Propofol is another option for RSE treatment. It is an alkylphenol that is a global CNS depressant. It activates GABA receptors and inhibits the NMDA receptors. Being highly lipophilic, it has fast onset, recovery, and a reliable entry in CNS. It is started with a loading dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg and then infused at 2 to 5 mg/kg/min, titrated to seizure suppression on EEG. It can be tapered down after 12 to 24 hours to check for resolution of refractory status. The drug is frequently employed as an anesthetic in the operating room and ICUs, making it a familiar agent to intensivists. Its use results in quick onset and recovery, and, unlike midazolam, it does not accumulate in the body over time. The short half life is due to redistribution followed by hepatic conjugation and renal excretion. A severe complication sometimes associated with the drug is Propofol infusion syndrome (PIS) which is characterized by severe metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, and cardiovascular collapse which can be fatal. A retrospective review at Mayo clinic found incidence of PIS to be 45%.[12] PIS is particularly likely if the dose used is >5 mg/kg/hr. Propofol should not be used in children, particularly those on ketogenic diet or in those patients who are on concurrent steroid or catecholamine therapy.[13] Other complications include infections like pneumonia, hypotension requiring vasopressors, rhabdomyolysis, and cardiac arrhythmia.[14]

The third commonly used agent in RSE is Pentobarbital. The initial dose is 5 mg/Kg IV followed by and infusion of 0.5-9 mg/kg/hour. Unlike midazolam and propofol, this medication is titrated to burst suppression pattern on EEG.[11] The half life is about 80 hours. Elimination is chiefly by hepatic microsomal enzyme system but 25-50% of the dose is excreted unchanged in urine. Pentobarbital also redistributes in the fat stores and accumulates with prolonged administration leading to a long wash out time. Zero order kinetics, metabolic autoinduction and various drug interactions make it a complicated drug to use. The major side effect is hypotension. Other effects include respiratory suppression and infection.

Randomized control trials comparing the three agents are lacking. Most the information is available through retrospective reviews. A review of literature form 1970s to 2001 by Claassen et al., found lower rates of treatment failure with pentobarbital (PTB) in comparison to midazolam or propofol. There was 8% treatment failure with PTB at six hours compared to 23 % for midazolam or propofol combined. The risk of breakthrough seizures was 12% with PTB and 42% with the latter. There was 7 times higher incidence of change in AED therapy in the latter compared to pentobarbital. But pentobarbital is associated with a 77% incidence of hypotension in comparison to 34% with midazolam or proprofol. However, of note, PTB was titrated to EEG burst suppression while midazolam and propofol were titrated to suppression of seizure activity. So it is not clear whether the drug or the goal of therapy resulted in better seizure control. Also more patients with NCSE were given midazolam while PTB group had more GCSE patients.

We tend to use Midazolam in preference to propofol or pentobarbital as the initial agent for RSE for the reasons mentioned above. However, propofol possesses some advantages with regard to ease of use and pharmacokinetic properties. Thiopental or Phenobarbital are usually reserved for use in severe cases. Some studies have found poorer outcomes where pentobarbital was used but this may be a biased conclusion based on the fact that it tends to be used in severe cases where prognosis may be poor due to the nature of the underlying etiology of the seizures.

There has also been an attempt to introduce the term “Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus” in scientific literature. It has been defined as refractory status epilepticus that has continued for more than 24 hours despite therapy. This term has however not yet gained widespread use in the United States.[15]

Other antiepileptic medications for treatment of status epilepticus

Levetiracetam has a parenteral formulation which has been studied as a treatment for status epilepticus[16,17] but there are no large randomized control studies to provide Level 1 evidence for its effectiveness in status epilepticus.

A retrospective study looked at 36 patients with RSE treated with intravenous levetiracetam after having failed at least one AED.[18] It was used at a median dose of 3,000 mg per day after a bolus loading dose of 500 to 2,000 mg. Outcome was favorable in 48%.

Another study from India looked at use of levetiracetam in RSE as a first line therapy as compared to lorazepam.[19] The study used intravenous levetiracetam at a dose of 20 mg/kg. Levetiracetam controlled SE in 70.0% (7/10) and Lorazepam in 88.9% (8/9) patients. There have also been earlier reports of using intravenous valproate in status epilepticus.

Lacosamide is another newer AED with availability of both enteral and parenteral formulations. For SE doses of 100 to 400 mg per day are used. It has a half life of 13 hours and is mainly excreted unchanged in urine. It is generally well tolerated and common side effects include ataxia, blurred vision, and somnolence. There are several case reports and case series of successful use of lacosamide in RSE.[20,21,22] However, a small case series at Johns Hopkins hospital did not find significant difference in outcomes with use of lacosamide.[23]

Inhalational anesthetics like isoflurane and desflurane have also been used in treatment of RSE. There is no general consensus on the dose and duration of therapy. For isoflurane, two small case series describe using end tidal volume ranges from 1.2 to 5.0% for up to 55 days.[24,25] There is now some concern of CNS toxicity when this agent is used for RSE.

There are also some reports of the use of NMDA antagonist Ketamine in status epilepticus.[26,27,28]

Adenosine is an endogenous anticonvulsant of the brain. It plays a role in seizure termination. Adenosine kinase (ADK) eliminates adenosine by phosphorylation to AMP; it is expressed predominantly in astrocytes. Thus, ADK inhibition or adenosine augmentation can be a therapeutic strategy to terminate or attenuate an SE.[29] Ketogenic diet reduces the expression of ADK and exercise augments the levels of adenosine in the brain and has been successfully tried in children[30,31] as well as adults.[32]

There is clearly a role for inflammation in status epilepticus. It is obvious in SE secondary to encephalitis – autoimmune and infectious.[33] There is study showing the benefit of utilizing an AED in conjunction with blood-brain-barrier stabilizing corticosteroid therapy in control of seizures.[34]

Lastly, various surgical approaches have been tried in RSE. These include hemispherectomy, multiple subpial transections, focal resection, lobar resection, corpus callosotomy, multilobar resection, and VNS placement.[35] The experience of surgery in RSE is limited. It has been used in cases of both focal and generalized seizures with etiologies like Tuberous Sclerosis, Rassmussen's syndrome, cortical dysplasia, and infarction.

Recent trials in status epilepticus

Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART) study showed that the efficacy of intramuscular midazolam is non-inferior to intravenous lorazepam when given to the patient before they reach the emergency room.[36]

There are two interesting trials being undertaken in status epilepticus. One is the Established Status Epilepticus Trial, which is a multicenter randomized study comparing the efficacy of fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, and valproic acid in established status epilepticus.[37] The second is the Treatment of Recurrent Electrographic Nonconvulsive Seizures study (TRENdS), which will evaluate the efficacy of lacosamide compared with fosphenytoin in the treatment of NCSE as measured by continuous EEG monitoring in critically ill patients.[38]

Outcome

In a retrospective study of 596 cases, RSE was shown to result in mortality in 35% cases.[39] 13% of the patients were left with severe neurological deficits while another 13% had mild neurological deficits. Only 35% patients recovered to baseline while 4% had undefined neurological deficits. Patients in RSE have higher lengths of stay in ICU and hospital and had lower Glasgow Coma Scales at discharge than patients with GCSE.

The morbidity and mortality associated with this entity make early recognition and aggressive treatment imperative. Continuous EEG monitoring is an essential tool in treatment of RSE to recognize non-convulsive status and adequately titrate medications. It is also an essential tool to recognize non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE). There has been an attempt to develop a unified EEG terminology for NCSE.[40]

SUMMARY

Though the definition of RSE varies, it is considered a medical emergency requiring aggressive treatment to avoid long-term complications and reduce mortality. Benzodiazepines remain the short-acting medications of choice for therapy initiation in SE followed by longer-acting medications (phenytoin or fosphenytoin, or phenobarbital in the case of phenytoin failure). Treatment options for patients who progress to RSE vary considerably, though midazolam, propofol, and pentobarbital are the most frequently utilized. Use of each medication includes a unique set of advantages and disadvantages, and as such, therapy should be individualized according to the seizure etiology (if known) and the individual patient's needs. Failure of one therapy does not predict response to other therapies and they should be given adequate trials sequentially unless contraindicated. There is no evidence on superiority of one approach to the other as yet.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy. Commission on epidemiology and prognosis, international league against epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34:592–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowenstein DH, Alldredge BK. Status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:970–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804023381407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassin S, Smith TL, Bleck TP. Clinical review: Status epilepticus. Crit Care. 2002;6:137–42. doi: 10.1186/cc1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer SA, Claassen J, Lokin J, Mendelsohn F, Dennis LJ, Fitzsimmons BF. Refractory status epilepticus, frequency, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:205–10. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg AT, Shinnar S, Levy SR, Testa FM. Status epilepticus in children with newly diagnosed epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:618–23. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199905)45:5<618::aid-ana10>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodkin HP, Yeh JL, Kapur J. Status epilepticus increases the intracellular accumulation of GABAA receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5511–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0900-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löscher W, Potschka H. Drug resistance in brain diseases and the role of drug efflux transporters. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrn1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujikawa DG. Prolonged seizures and cellular injury: Understanding the connection. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(Suppl 3):S3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treiman DM, Meyers PD, Walton NY, Collins JF, Colling C, Rowan AJ, et al. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans affairs status epilepticus cooperative study group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:792–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, Corry MD, Allen F, Ulrich S, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:631–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Emerson RG, Mayer SA. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with pentobarbital, propofol, or midazolam: A systematic review. Epilepsia. 2002;43:146–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.28501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer VN, Hoel R, Rabinstein AA. Propofol infusion syndrome in patients with refractory status epilepticus: An 11-year clinical experience. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3024–30. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b08ac7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumeister FA, Oberhoffer R, Liebhaber GM, Kunkel J, Eberhardt J, Holthausen H, et al. Fatal propofol infusion syndrome in association with ketogenic diet. Neuropediatrics. 2004;35:250–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Power KN, Flaatten H, Gilhus NE, Engelsen BA. Propofol treatment in adult refractory status epilepticus. Mortality risk and outcome. Epilepsy Res. 2011;94:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shorvon S. Super-refractory status epilepticus: An approach to therapy in this difficult clinical situation. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 8):53–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallentine WB, Hunnicutt AS, Husain AM. Levetiracetam in children with refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:215–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rösche J, Pohley I, Rantsch K, Walter U, Benecke R. Experience with levetiracetam in the treatment of status epilepticus. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2013;81:21–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1312951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Möddel G, Bunten S, Dobis C, Kovac S, Dogan M, Fischera M, et al. Intravenous levetiracetam: A new treatment alternative for refractory status epilepticus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:689–92. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.145458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra UK, Kalita J, Maurya PK. Levetiracetam versus lorazepam in status epilepticus: A randomized, open labeled pilot study. J Neurol. 2012;259:645–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albers JM, Möddel G, Dittrich R, Steidl C, Suntrup S, Ringelstein EB, et al. Intravenous lacosamide - an effective add-on treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Seizure. 2011;20:428–30. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Höfler J, Trinka E. Lacosamide as a new treatment option in status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2013;54:393–404. doi: 10.1111/epi.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellinghaus C, Berning S, Besselmann M. Intravenous lacosamide as successful treatment for nonconvulsive status epilepticus after failure of first-line therapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:429–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodwin H, Hinson HE, Shermock KM, Karanjia N, Lewin JJ., 3rd The use of lacosamide in refractory status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14:348–53. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kofke WA, Young RS, Davis P, Woelfel SK, Gray L, Johnson D, et al. Isoflurane for refractory status epilepticus: A clinical series. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:653–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirsattari SM, Sharpe MD, Young GB. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with inhalational anesthetic agents isoflurane and desflurane. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1254–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaspard N, Foreman B, Judd LM, Brenton JN, Nathan BR, McCoy BM, et al. Intravenous ketamine for the treatment of refractory status epilepticus: A retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1498–503. doi: 10.1111/epi.12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Synowiec AS, Singh DS, Yenugadhati V, Valeriano JP, Schramke CJ, Kelly KM. Ketamine use in the treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2013;105:183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosati A, L’Erario M, Ilvento L, Cecchi C, Pisano T, Mirabile L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine in refractory status epilepticus in children. Neurology. 2012;79:2355–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278b685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boison D. Role of adenosine in status epilepticus: A potential new target? Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 6):20–2. doi: 10.1111/epi.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kossoff EH, Nabbout R. Use of dietary therapy for status epilepticus. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1049–51. doi: 10.1177/0883073813487601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wheless JW. Treatment of refractory convulsive status epilepticus in children: Other therapies. Semin in Pediatr Neurol. 2010;17:190–4. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wusthoff CJ, Kranick SM, Morley JF, Christina Bergqvist AG. The ketogenic diet in treatment of two adults with prolonged nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1083–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gall CR, Jumma O, Mohanraj R. Five cases of new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) syndrome: Outcomes with early immunotherapy. Seizure. 2013;22:217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchi N, Granata T, Freri E, Ciusani E, Ragona F, Puvenna V, et al. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory therapy in a model of acute seizures and in a population of pediatric drug resistant epileptics. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X, Liporace J, O’Connor MJ, Sperling MR. Neurosurgical treatment of medically intractable status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2001;46:33–8. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silbergliet R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch Y, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 366:591–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bleck T, Cock H, Chamberlain J, Cloyd J, Connor J, Elm J, et al. The established status epilepticus trial 2013. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 6):89–92. doi: 10.1111/epi.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husian AM. Treatment of recurrent electrographic nonconvulsive seizures (TRENdS) study. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 6):84–8. doi: 10.1111/epi.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferlisi M, Shorvon S. The outcome of therapies in refractory and super-refractory convulsive status epilepticus and recommendations for therapy. Brain. 2012;135:2314–28. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beniczky S, Hirsch LJ, Kaplan PW, Pressler R, Bauer G, Aurlien H, et al. Unified EEG terminology and criteria for nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 6):28–9. doi: 10.1111/epi.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]