ABSTRACT

We previously found that the small GTPase Ras-dva1 is essential for the telencephalic development in Xenopus laevis because Ras-dva1 controls the Fgf8-mediated induction of FoxG1 expression, a key telencephalic regulator. In this report, we show, however, that Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 are expressed in different groups of cells; whereas Ras-dva1 is expressed in the outer layer of the anterior neural fold, FoxG1 and Fgf8 are activated in the inner layer from which the telencephalon is derived. We resolve this paradox by demonstrating that Ras-dva1 is involved in the transduction of Fgf8 signal received by cells in the outer layer, which in turn send a feedback signal that stimulates FoxG1 expression in the inner layer. We show that this feedback signal is transmitted by secreted Agr proteins, the expression of which is activated in the outer layer by mediation of Ras-dva1 and the homeodomain transcription factor Otx2. In turn, Agrs are essential for maintaining Fgf8 and FoxG1 expression in cells at the anterior neural plate border. Our finding reveals a novel feedback loop mechanism based on the exchange of Fgf8 and Agr signaling between neural and non-neural compartments at the anterior margin of the neural plate and demonstrates a key role of Ras-dva1 in this mechanism.

Keywords: Forebrain development, Anterior neural border, Agr, Fgf8, FoxG1, Otx2, Ras-dva

INTRODUCTION

In vertebrate embryos, a stripe of cells located at the anterior neural plate border (ANB) is an important developmental organizer, which generates the Fgf8-based signal that regulates patterning of the presumptive rostral forebrain, including the telencephalon and the anterior part of the diencephalon (Cavodeassi and Houart, 2012).

Recently, we have shown that in the Xenopus laevis embryo, the small GTPase Ras-dva1, which is expressed near ANB, is necessary for the Fgf8-mediated expression of the telencephalic regulator FoxG1 (previously named BF1) in cells at the anterior margin of the neural plate (Tereshina et al., 2006). This expression pattern indicates that Ras-dva1, which is a membrane-bound GTPase (Tereshina et al., 2007), might control the propagation of Fgf8 signal within these cells, composing the telencephalic rudiment. As we now demonstrate, however, Ras-dva1 is not co-expressed with FoxG1 in the presumptive telencephalic cells. The expression of Ras-dva1 occurs exclusively in the non-neural cells in the presumptive cement and hatching glands, which compose the outer layer of the rostral part of the anterior neural fold and the adjacent non-neural ectoderm surrounding the neural fold at the anterior. Therefore, we hypothesized that Ras-dva1 might control the expression of FoxG1 non-autonomously via regulation of some unknown signal sent by the non-neural cells to the adjacent cells in the presumptive telencephalon.

By using gain- and loss-of-function approaches, we tested this hypothesis and found that the presumptive telencephalic cells induce the expression of Ras-dva1 through secreted Fgf8 in cells of the adjacent non-neural ectoderm. As a result, the Ras-dva1-mediated Fgf8 signal induces the expression of the homeobox gene Otx2 in these cells. In turn, Otx2 activates genes encoding the Agr secreted factors, Xag and Xagr2, which belong to the superfamily of protein disulfide isomerases and supposedly to modulate protein folding, but also possess an independent signaling activity (Blassberg et al., 2011; Hatahet and Ruddock, 2009; Persson et al., 2005; Vanderlaag et al., 2010). We demonstrate that Xag and Xagr2 are required for the Fgf8-dependent activation of FoxG1 expression in the presumptive telencephalic cells. An interruption in this signaling feedback loop at any step, and in particular downregulation of Ras-dva1 expression, leads to severe malformations of the rostral forebrain, as well as abnormalities of the structures deriving from the non-neural anterior ectoderm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs, synthetic mRNAs and morpholino oligonucleotides

All plasmids were described previously (Ermakova et al., 1999; Ermakova et al., 2007; Ivanova et al., 2013; Novoselov et al., 2003; Tereshina et al., 2006). Synthetic capped mRNA and anti-sense RNA dig-labeled probes for in situ hybridization were prepared by using mMessage Machine Kits (Ambion). RNA templates were purified by the RNeasy Mini Column Kit (QIAGEN). Embryos were injected at the 8- or 16-cell stages with 8 or 4 nl per blastomere of mRNA water solution, respectively. The mRNA concentrations were 50 pg/nl of FGF8a and 60 pg/nl of each Agrs and Ras-dva1 mRNAs. The Morpholino Oligonucleotides (MO) were from Gene Tools LLC (see supplementary material Table S1 for MO sequences). All MOs were dissolved in RNAse-free water to a concentration of 0.4 mM, mixed before injection with Fluorescein Lysine Dextran (FLD) (Invitrogen, 40 kDa, 5 mg/ml) tracer and injected into blastomeres at volumes of either 4 nl (at 16-cell stage) or 8 nl (at 8-cell stage). In case when the mixture of Xag and Xagr2 MO was injected, the final concentration of each MO was 0.2 mM.

To construct templates for testing the efficiency of Xag and Xagr2 MOs, cDNA fragments containing the MO target sites along with open reading frames of Xag2 and Xagr2A were obtained by PCR, cloned into the Evrogen pTagRFP-N vector (cat. no. FP142) by EcoRI and AgeI upstream and in-frame of the TagRFP cDNA, followed by recloning of the Xag2-TagRFP and Xagr2-TagRFP cassettes (excised by EcoRI and blunted NotI) into EcoRI and blunted XhoI sites of the pCS2+ vector. Capped mRNA encoding Xag2-TagRFP and Xagr2-TagRFP was synthesized with SP6 Message Machine Kit (Ambion) using the obtained plasmids cut by NotI. The resulting mRNA was injected into dorsal blastomeres of 8-cell embryos (100 pg/blastomere) either alone or in a mixture with the corresponding MO (8 nl of 0.4 mM water solution) (supplementary material Fig. S1A). The injected embryos were collected at the midneurula stage and analyzed for the presence of Xag2-TagRFP and Xagr2-TagRFP by Western blotting with Evrogen tRFP antibody (cat. no. AB233) as described (Bayramov et al., 2011). As a result, the complete suppression of Xag2-TagRFP and Xagr2-TagRFP mRNA translation was observed in embryos co-injected with the corresponding anti-sense MO (supplementary material Fig. S1). In contrast, no inhibition was observed if mis-Xag, mis-Xagr2 or a standard control MO was co-injected.

Transgenic embryos and in situ hybridization

To generate constructs expressing Xanf1 or dnRas-dva1 under the control of the Xenopus laevis Xag2 promoter, cDNA fragments encoding these proteins were obtained by PCR and sub-cloned together with a 1.2 kb fragment of Xag2 promoter into the pRx-GFP-pCA-RFP double-cassette vector (a gift from R. Grainger) in place of the Rx-GFP cassette. Transgenic embryos bearing the resulting constructs, pXag2-Xanf1-pCA-RFP and pXag2-DNRas-dva1-pCA-RFP, were generated as described (Martynova et al., 2004; Offield et al., 2000); transgenic embryos were selected either by performing in situ hybridization with the probe of interest mixed with a RFP probe or by observing red fluorescence in the skeletal muscles of the tadpoles (Ermakova et al., 2007).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as described (Harland, 1991), mainly with dig- and in case of the double in situ also with fluorescein-labeled probes. For in situ hybridization on left and right halves of individual embryos, the embryos were dissected along the medial sagittal plane and processed as described (Tereshina et al., 2006). For in situ hybridization of tissue sections, embryos were first embedded in 4% agarose and then dissected on a vibratome into 20 µm serial, sagittal sections; the central pair of adjacent sections from each embryo were selected and processed individually for in situ hybridization as described (Harland, 1991).

RESULTS

Ras-dva1 regulates rostral forebrain development via a non-autonomous mechanism

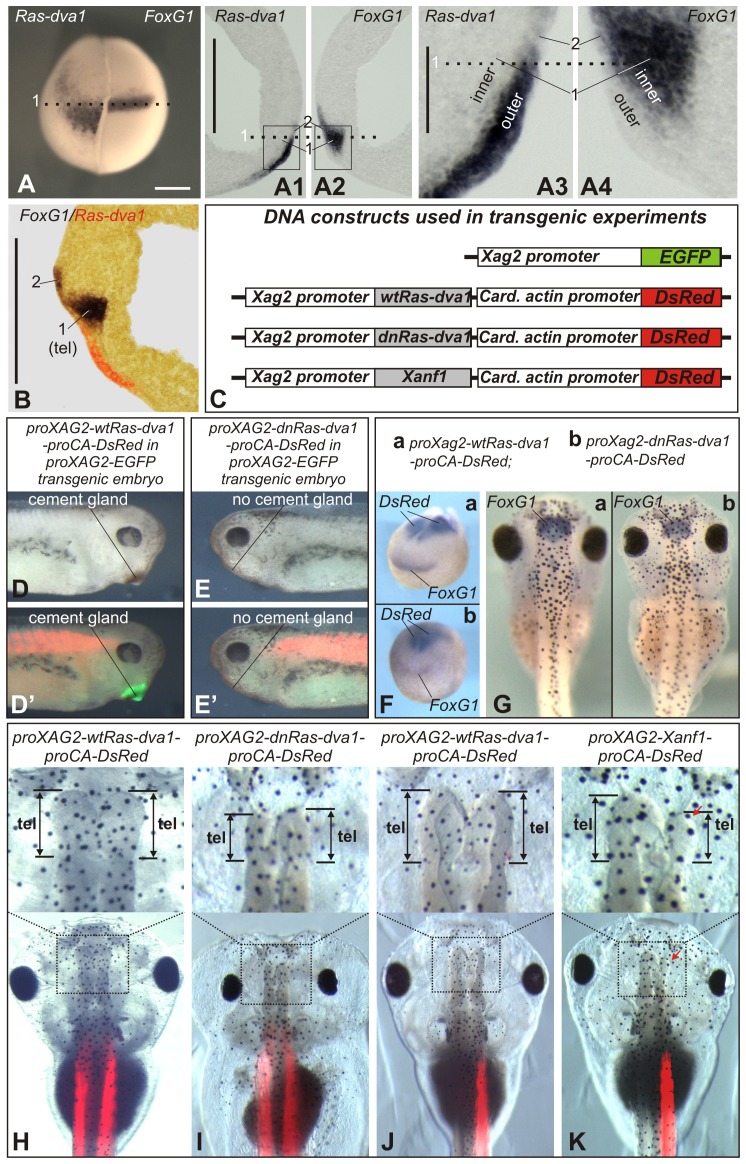

When analyzing FoxG1 and Ras-dva1 expression in whole mount embryos, one may conclude that these genes are co-expressed in same anterior neural fold cells (Fig. 1A). However, we have found that this conclusion is not correct because these genes are mostly expressed in different groups of cells. Namely, beginning from the gastrula stage and till at least tailbud stage, Ras-dva1 is intensively expressed exclusively in cells in the outer layer of the non-neural ectoderm (Fig. 1A1,A3,B; supplementary material Fig. S1B1,E1), which during neurulation partially overlaps the rostral part of the underlying inner layer of the anterior neural fold, where FoxG1 is expressed and from which the telencephalon derives (zone 1 in Fig. 1A1–A4,B; zone 1 in supplementary material Fig. S1I,K1,K3). In addition, lower expression of FoxG1 and Ras-dva1 was observed in a scattered stripe of the outer layer cells, located posterior to cells intensively expressing Ras-dva1 (zone 2 in Fig. 1A1–A4,B; zone 2 in supplementary material Fig. S1I,K1,K3). Importantly, these outer cells, in which both FoxG1 and Ras-dva1 are expressed, further give rise to the diencephalon (supplementary material Fig. S1K5), but not to the telencephalon (G. Eagleson, personal communication; see also Eagleson et al., 1995; Eagleson and Harris, 1990; Eagleson et al., 1986). Thus, Ras-dva1 is not co-expressed with FoxG1 directly in the telencephalic primordium.

Fig. 1. Ras-dva1 is expressed in the non-neural anterior ectoderm and regulates forebrain development by a cell non-autonomous mechanism.

(A) In situ hybridization with dig-labeled probes to Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 on the left and right halves of the same embryo. Upon completing the in situ hybridization procedure, the two halves of the embryo were stacked together and photographed from the anterior with the dorsal side upward. The dotted line corresponds to the dotted lines in panels A1–A4. (A1,A2) Adjacent vibratome medial sagittal sections of the same embryo were hybridized separately with Ras-dva1 (left section) or FoxG1 (right section) probe. Anterior sides face each other, dorsal sides up. “1” indicates region of the inner layer in which only FoxG1 is expressed. “2” indicates region of the outer layer in which Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 are co-expressed. (A3,A4) Enlarged images of fragments squared in panels A1 and A2. (B) In situ hybridization with dig- and fluorescein-labeled probes to Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 on the vibratom medial sagittal section of the midneurula (stage 15) embryo. (C) Schemas of DNA constructs used to generate transgenic embryos shown in panels C–J. (D–E′) Whereas no cement gland inhibition is seen in control embryo of transgenic line bearing proXag2-EGFP construct and transfected by proXag2-wtRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed (D,D′), the embryo of the same line but transfected by proXAG2-dnRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed construct has no cement gland (E,E′). (F) No inhibition of FoxG1 expression is seen in the early neurula embryo bearing the control transgene (proXag2-wtRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed) (a). In contrast, a decrease of FoxG1 expression is observed in the embryo transfected with proXAG2-dnRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed (b). Whole-mount in situ hybridization with probes to both FoxG1 and DsRed. (G) Transgenic tadpole bearing the control proXag2-wtRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed construct has normal sized telencephalon marked by FoxG1 expression. At the same time, a reduction of the telencephalon and FoxG1 is seen in embryo bearing proXAG2-dnRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed construct. Transgenic tadpoles were selected by revealing DsRed fluorescence and hybridized in whole-mount with the probe to FoxG1. (H–K) The telencephalons (upper row) and whole heads (bottom row) of the 5-day tadpoles bearing transgenic constructs indicated on the top. Scale bars: 200 µm (A–A2,B), 40 µm (A3,A4).

In contrast to the spatial complementarity of the Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 expression domains, the activity of Ras-dva1 appears to be critical for FoxG1 expression and telencephalon development. Thus, injections of antisense MO or an mRNA encoding the dominant-negative variant of Ras-dva1 (dnRas-dva1) led to a reduction in the telencephalon, eyes and other anterior structures (Tereshina et al., 2006). These results indicate that Ras-dva1 may regulate FoxG1 expression and forebrain development by a non-autonomous mechanism.

To more clearly demonstrate the non-autonomous character of this mechanism, we precisely inhibited Ras-dva1 expression in cells of the outer layer. To this end, we created transgenic embryos in which either wild-type Ras-dva1, its dominant-negative mutant dnRas-dva1 (Tereshina et al., 2006), or the natural inhibitor of Ras-dva1, the homeodomain transcriptional repressor Xanf1 (Ermakova et al., 1999; Tereshina et al., 2006), was expressed under the control of a 1.2 kb fragment of Xag2 promoter (Fig. 1C). As we have shown previously, this promoter fragment is sufficient to specifically target the expression of the fluorescent reporter to cells in the presumptive hatching and cement gland domains, located in the outer layer of the non-neural anterior ectoderm, in which Ras-dva1 is expressed (Ivanova et al., 2013; Serebrovskaya et al., 2011).

The DNA cassette, composed of the Xag2 promoter attached to either wild-type Ras-dva1, dnRas-dva1 or Xanf1 cDNA, was a part of the double-cassette vector; the second cassette contains the DsRed red fluorescent protein cDNA (Matz et al., 1999) under the control of the Cardiac Actin promoter (Fig. 1C). The DsRed expression cassette helped us to distinguish transgenic embryos from the non-transgenic ones by detecting DsRed RNA (at early stages) or by fluorescence (at late stages).

When transgenic embryos were obtained, we found that approximately 40% and 50% (28 and 35) of embryos bearing proXag2-dnRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed and proXag2-Xanf1-proCA-DsRed constructs, respectively, had no cement glands (Fig. 1D–E′; supplementary material Fig. S2A–C). In addition, and in contrast to transgenic embryos expressing the wild-type Ras-dva1, approximately 45% of those expressing transgenic dnRas-dva1 and 60% expressing Xanf1 (n = 24 and 21, respectively) demonstrated inhibition of expression of the forebrain regulator FoxG1 (Fig. 1F; supplementary material Fig. S2D). A reduction in the FoxG1 expression zone was also observed in tadpoles developed from these embryos (10/15 and 12/17) (Fig. 1G; supplementary material Fig. S2E). Consistently, transgenic tadpoles bearing the proXag2-dnRas-dva1-proCA-DsRed and proXag2-Xanf1-proCA-DsRed constructs had reduced telencephalons and eyes (21/30 and 26/32), i.e. the forebrain abnormalities resembling those observed earlier in embryos injected with dnRas-dva1 mRNA or Ras-dva1 MO (Tereshina et al., 2006) (Fig. 1H–K) These effects were especially evident in accidentally appearing embryos, having transgenic constructs in cells of only left or right side of the body. In these embryos, non-transgenic halves may serve as internal controls (Fig. 1J,K). Taken together, these results confirm the non-autonomous character of the mechanism by which Ras-dva1 regulates forebrain development.

Ras-dva1 mediates the Fgf8-dependent induction of Agrs expression in the outer layer of the non-neural anterior ectoderm

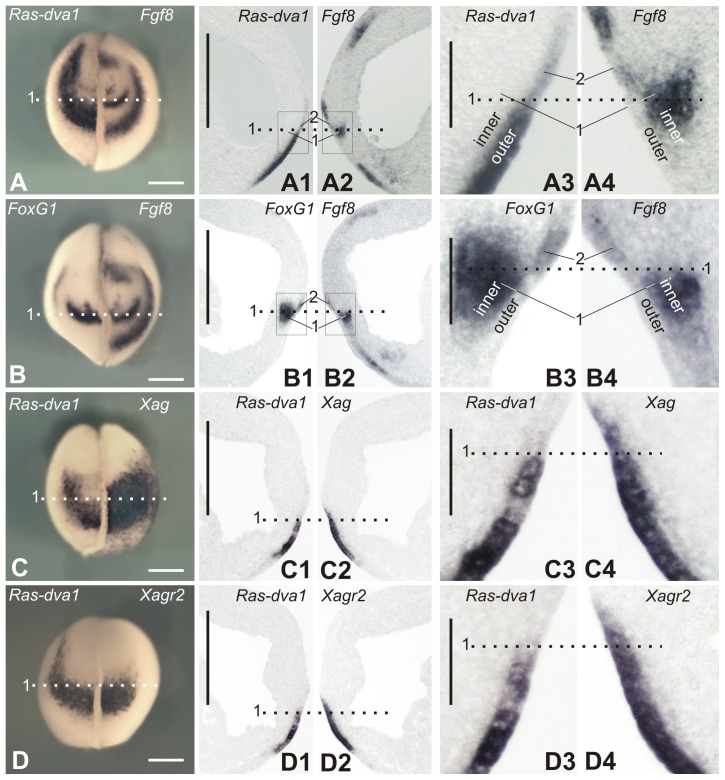

As we have demonstrated previously, downregulation of Ras-dva1 can block the induction of FoxG1 expression elicited by ectopic Fgf8a (Tereshina et al., 2006). Together with the present data suggesting the non-autonomous character of the Ras-dva1-mediated stimulation of FoxG1 expression in the telencephalic primordium, this result indicates that the role of Ras-dva1 in this process may be in the transmission of the Fgf8 signal within cells in the outer layer, thereby programming them to initiate some feedback signal, which in turn induces cells in the inner layer to express FoxG1. Consistently, similarly to FoxG1, Fgf8 is expressed in cells of the inner layer of the anterior neural fold from which the telencephalon derives (zone 1 in Fig. 2A2,A4,B2,B4). In contrast to FoxG1, however, a low Fgf8 expression can be also seen in the inner layer, in a region entirely underlying the territory of the cement gland placode in the outer layer, in which Ras-dva1 is expressed most intensively (compare Fig. 2A2 with Fig. 2B3). Similarly to FoxG1, low Fgf8 expression is revealed in non-telencephalic cells of outer layer, in which Ras-dva1 is also expressed (zone 2 in Fig. 2A2,A4,B2,B4; zone 2 in supplementary material Fig. S1J,K2,K4).

Fig. 2. Pairwise comparison of expression patterns of genes expressed in the anterior ectoderm at the midneurula stage.

(A–D) Whole-mount in situ hybridization with probes to transcripts of the indicated pairs of genes on the left and right halves of individual embryos as it is described in Fig. 1A. (A1–D1,A2–D2) In situ hybridization on adjacent vibratome sagittal sections of individual embryos with probes to indicated pairs of transcripts. Note that panels C1,D1,C2,D2 show results of hybridization made on two pairs of adjacent sections of the same embryo. (A3–D3,A4–D4) Enlarged images of fragments framed in panels A1–D1 and A2–D2. For abbreviations, see Fig. 1A–A4. Scale bars: 200 µm (A–D2), 40 µm (A3–D4).

The hypothetical feed-back signal produced by the outer layer cells could be transmitted by some factor(s) secreted by these cells. We supposed that the role of such factors could play secreted Agr proteins, which belong to the superfamily of protein disulfide isomerases (Persson et al., 2005). The reasoning for this hypothesis is that first, Agrs are expressed in a similar region of the anterior ectoderm as Ras-dva1, and second, at least one of the Xenopus Agrs, Xag2, was shown to induce anterior neural fate in the embryonic ectoderm through a Fgf signaling-dependent manner (Aberger et al., 1998).

Those of Agrs that are expressed during gastrulation and neurulation are represented in the Xenopus laevis genome by two pairs of very homologous pseudoalleles, Xag1/Xag2 and Xagr2a/Xagr2b (further referred to as Xag and Xagr2, respectively) (Ivanova et al., 2013). As we have identified by in situ hybridization, these genes are indeed co-expressed with Ras-dva1 in cells in the outer layer of the anterior ectoderm, which further give rise to the cement and hatching glands (Fig. 2C–C6,D–D6; supplementary material Fig. S1B2,F,H1). Importantly, although Agrs, like Ras-dva1, are co-expressed with FoxG1 and Fgf8 in the outer layer of the anterior neural ridge, no expression of these genes were detected in cells of the telencephalic primordium located in the inner layer of the ridge (supplementary material Fig. S1H2). Thus, the secreted protein products of Agrs could potentially play a role as the proposed signaling factors regulated by Ras-dva1.

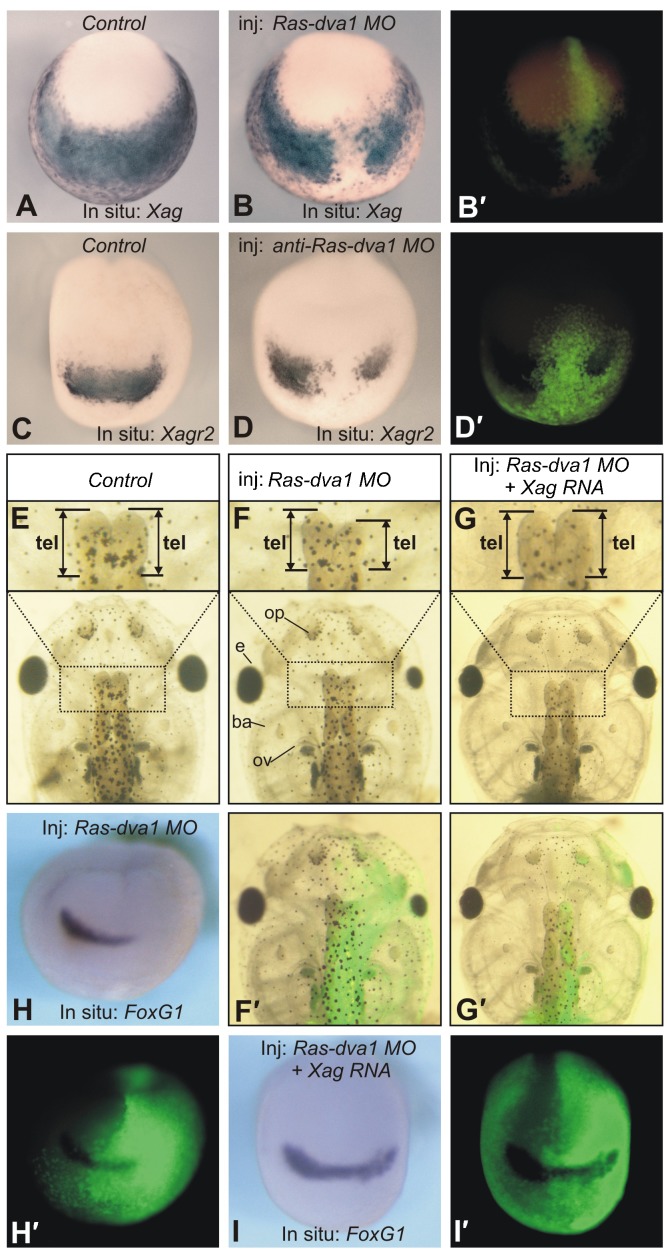

To verify whether Ras-dva1 activity is necessary to induce Agrs expression, we first tested whether downregulation of Ras-dva1 could influence their expression. When embryos were injected with Ras-dva1 MO, a severe downregulation of Xag, Xagr2 and FoxG1 at the midneurula stage (20/23, 25/28, 23/25) and a reduction of the telencephalon and eyes of tadpoles (31/39) were observed (Fig. 3A,B,C,D,E,F,H). In contrast, no abnormalities were seen when the control misRas-dva1 MO was injected (see supplementary material Fig. S3 for results of injections of this and other control MO). Importantly, a rescue of these abnormalities, including normalization of the expression pattern of FoxG1 and a restoration of the wild-type forebrain phenotype, was observed when Ras-dva1 MO was co-injected with either Xagr2 or Xag mRNA (here and below designates Xagr2A and equimolar mixture of Xag1 and Xag2, respectively) (22/35 and 23/34) (Fig. 3G,I and data not shown). This result indicates that Agrs is downstream of Ras-dva1 in the mechanism regulating the forebrain development.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of Ras-dva1 mRNA translation by the Ras-dva1 morpholino elicits the downregulation of Agrs and a reduction of the forebrain.

(A,C) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of midneurula control embryos with dig-labeled probes to Xag and Xagr2, respectively. Anterior view with dorsal side upward. (B,B′,D,D′) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of the Ras-dva1 MO-injected midneurula embryos with dig-labeled probes to Xag and Xagr2, respectively. Fluorescent images in panels B′ and D′ demonstrate distribution of cell clones containing the co-injected FLD fluorescent tracer. (E) The telencephalon (upper row) and whole head of the control 5-day tadpole. Dorsal view, anterior to the top. (F,F′) The telencephalon (upper row) and whole head of the 5-day tadpole developed from the embryos injected with Ras-dva1 MO into the right dorsal blastomere at the 8-cell stage. Note the reduced telencephalon and eye on the injected side. The fluorescent image in panel F demonstrates the distribution of cell clones containing the co-injected FLD fluorescent tracer. (G,G′) Rescue of the Ras-dva1 MO-induced abnormalities by the co-injection of Ras-dva1 mRNA. Note the normal telencephalon and eye on the injected side (see distribution of the injected cells in panel G′). (H,H′) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of the Ras-dva1 MO-injected midneurula embryos with dig-labeled probes to FoxG1. Note the inhibition of FoxG1 expression on the injected side. See the distribution of cell clones containing the co-injected FLD fluorescent tracer in panel H′. (I,I′) Rescue of the Ras-dva1 MO-induced inhibition of FoxG1 expression by the co-injection of Ras-dva1 mRNA. See the distribution of cell clones containing the co-injected FLD fluorescent tracer in panel I′.

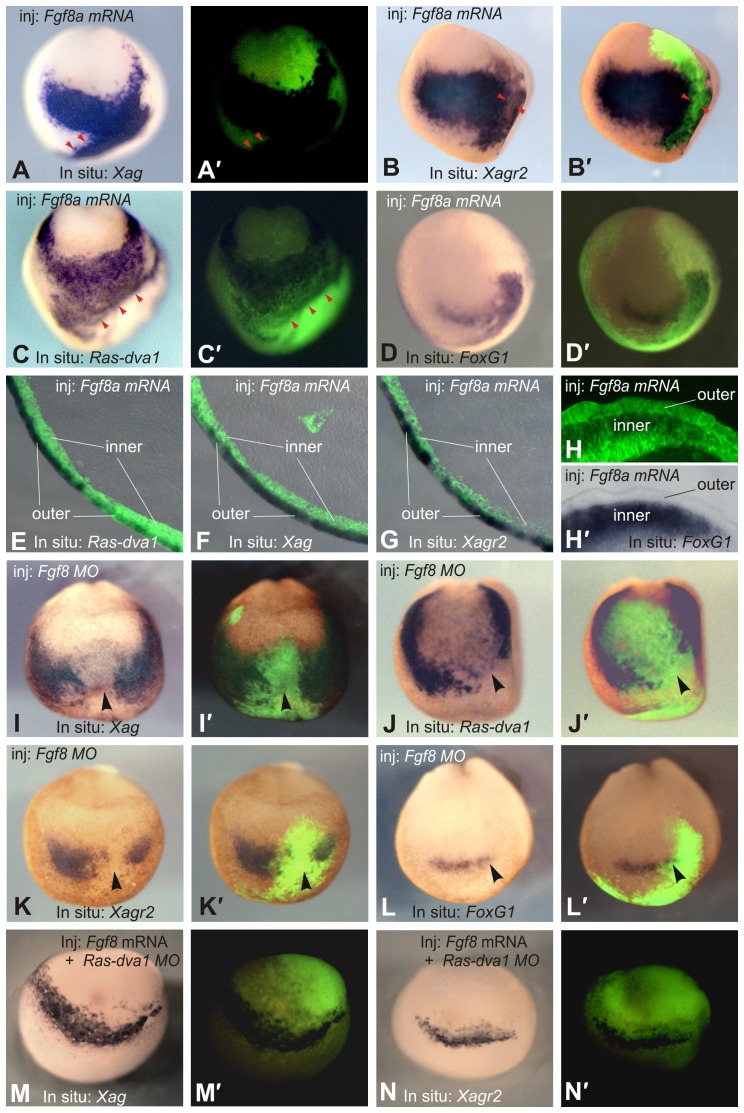

If the Ras-dva1-mediated expression of Agrs in the non-neural cells is activated by Fgf8 signaling, then disturbances in this signaling might also influence Agrs expression. To test this prediction, we examined whether Fgf8 can activate expression of Xag and Xagr2 in the anterior ectoderm of midneurula embryos injected with Fgf8a mRNA. Indeed, we observed strong ectopic induction of Xag and Xagr2 expression in cells in the non-neural ectoderm (25/26 and 23/24) (Fig. 4A,B). Importantly, the expression of Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 appears to also be ectopically activated, confirming involvement of all four genes in the same regulatory pathway (Fig. 4C,D). Remarkably, in contrast to the ectopically induced expression of FoxG1, the expression of Agrs and Ras-dva1 was observed not in Fgf8 expressing cells but in cells at the direct periphery of the Fgf8 expressing cells (arrowheads in Fig. 4B,C). Interestingly, as one may see in the histological sectioning of these embryos, whereas Ras-dva1, Xag and Xagr2 are activated only in the outer layer of the ectoderm, ectopic FoxG1 is induced exclusively in the inner layer (Fig. 4E–H). These results also confirmed that FoxG1 is expressed in relation to Ras-dva1, Xag and Xagr2 in a spatially complementary pattern.

Fig. 4. Fgf8 regulates the expression of FoxG1, Ras-dva1, Xag and Xagr2.

(A–D) Injections of Fgf8a mRNA elicit ectopic expression of FoxG1, Ras-dva1, Xag and Xagr2 in the anterior ectoderm of the midneurula stage embryos. Fgf8a mRNA mixed with FLD tracer was injected at concentration of 20 pg/blastomere in a pair of adjacent animal dorsal and ventral blastomeres on the left sides of 16- to 32-cell stage embryos. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed at the midneurula stage. Anterior view with the dorsal side upward. (A′–D′) Overlays of the white light and fluorescent images of embryos shown in panels A–D. Red arrowheads in panels A and C indicate the borders of ectopic expression, which correspond to the borders of cell clones with strong fluorescence. (E–H) Vibratome sections of embryos injected with Fgf8a mRNA. Note that whereas Ras-dva1, Xag and Xagr2 are activated only in the outer layer of the ectoderm (E–G, overlays of bright light and fluorescent images), ectopic FoxG1 is induced exclusively in the inner layer (H,H′). (I–L) Injection of Fgf8a MO leads to inhibition of FoxG1, Ras-dva1, Xag and Xagr2 expression. An Fgf8a MO (1–2 pmol/blastomere) was injected with a FLD tracer in a pair of adjacent animal dorsal and ventral blastomeres on the left sides of 16- to 32-cell stage embryos. (M,N) Co-injection of Fgf8 mRNA is unable to rescue inhibition of Xag and Xagr2 expression elicited by Ras-dva1 MO. The black arrowheads indicate sites of expression inhibition.

Conversely, we observed inhibition of Xag, Xagr2, Ras-dva1 and FoxG1 expression when translation of Fgf8 mRNA was suppressed by injection of Fgf8 MO in the left or right pair of adjacent dorsal and ventral animal blastomeres at the 16- to 32-cell stage (the presumptive left or right half of the anterior ectoderm) (23/26, 24/27, 22/23 and 20/26, respectively) (Fig. 4I–L).

These results corroborate our working hypothesis predicting that Fgf8-dependent induction of Agrs expression is mediated by the Ras-dva1 activity. Additionally, these experiments revealed that the expression of Ras-dva1 itself is under the control of Fgf8 signaling.

To confirm that Ras-dva1 mediates the induction of Agrs expression by Fgf8, we investigated whether downregulation of Ras-dva1 can interrupt induction of the ectopic expression of Agrs by Fgf8. Indeed, most embryos injected with a mixture of Fgf8 mRNA and Ras-dva1 MO did not demonstrate ectopic expression of Xag and Xagr2 (24/25 and 23/27). Moreover, we observed partial downregulation of Xag expression in the injected side of some of the latter embryos (14/25 and 18/27) (Fig. 4M,N).

Based on these data, we concluded that the Fgf8 signal produced by cells of the anterior neural plate is essential for the induction of Agrs and Ras-dva1 expression in cells in the outer layer of the adjacent non-neural ectoderm, and the activity of Ras-dva1 within the latter cells is crucial for this induction.

Downregulation of Agrs elicits abnormalities similar to those observed in embryos with inhibited Ras-dva1 function

Our experiments described above demonstrate that Xag and Xagr2 are located downstream of Fgf8 and Ras-dva1 in the signaling pathway that regulates FoxG1 expression. This result indicates that in normal development Agr proteins produced by cells in the non-neural ectoderm could be responsible for stimulating FoxG1 expression in cells of the presumptive telencephalon. To verify this prediction, loss-of-function experiments were performed by injecting Xag and Xagr2 MO.

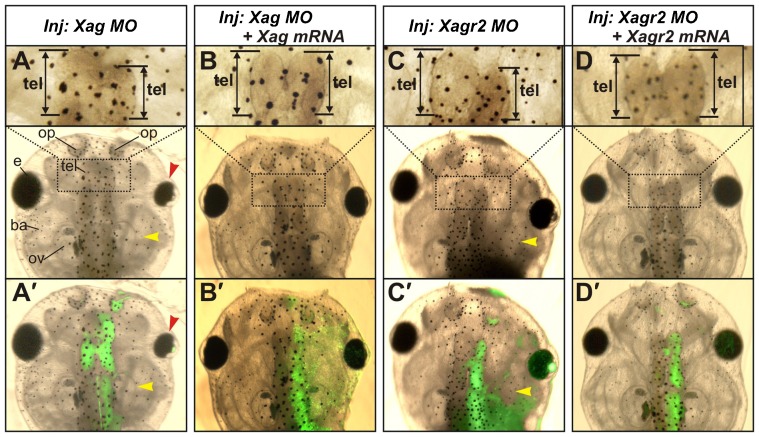

When Xag MO was injected, we observed head malformations, including partial reduction of the telencephalon, olfactory pit, otic vesicle, eye and branchial arches (110/120) (Fig. 5A). These malformations resembled those observed in experiments with downregulated Ras-dva1 (Tereshina et al., 2006). In contrast, injections of Xagr2 MO primarily caused a reduction in the telencephalon, olfactory pits and otic vesicles (85/95), while branchial arches and eyes were reduced only in a small portion of embryos (9/95) (Fig. 5C). In spite of this difference, which could likely be explained by broader expression domains of Xag than Xagr2 (Novoselov et al., 2003) or by some functional difference between these two proteins, these results confirm the importance of both Xag and Xagr2 for the forebrain development.

Fig. 5. Inhibition of Xag and Xagr2 mRNA translation by anti-sense morpholinos elicits brain abnormalities similar to those observed when Ras-dva1 and Fgf8 were inhibited.

(A,C) Inhibition of Xag (A) and Xagr2 (C) mRNA translation by anti-sense morpholinos elicits reduction of the telencephalon (see enlarged images in the upper row, black arrow), otic vesicles (yellow arrowhead) and eyes (red arrowhead for Xag downregulation). (A′,C′) Overlays of the white light and fluorescent images of embryos shown in panels A and C demonstrate the distribution of cells containing injected MO mixed with a FLD tracer. (B,D) Rescue of anatomical abnormalities by co-injection of Xag and Xagr2 mRNAs with Xag and Xagr2 morpholinos to these genes. (B′,D′) Overlays of the white light and fluorescent images of embryos shown in panels B and D demonstrate the distribution of cells containing the injected MO mixed with a FLD tracer.

To test specificity of Xag and Xagr2 MO effects, rescue experiments were performed by co-injecting these MOs with Xag or Xagr2 mRNAs deprived of the MO target sites. As a result, a 50% rescue of the abnormalities induced by the MO injected alone was observed in both cases (35/72 and 28/55, respectively) (Fig. 5B,D). In addition, co-injection of same MOs with Ras-dva1 mRNA did not cause any rescue (0/64) (data not shown). Notably, co-injections of Xag mRNA or Xagr2 mRNA with Ras-dva1 MO resulted in a 50% rescue (34/70 and 33/65) of abnormalities elicited by this MO injected alone (20/23 and 25/28) (Fig. 3G,I). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that positions Ras-dva1 upstream of Agrs in the regulatory pathway.

Agrs, Fgf8 and Ras-dva1 regulate expression of each other

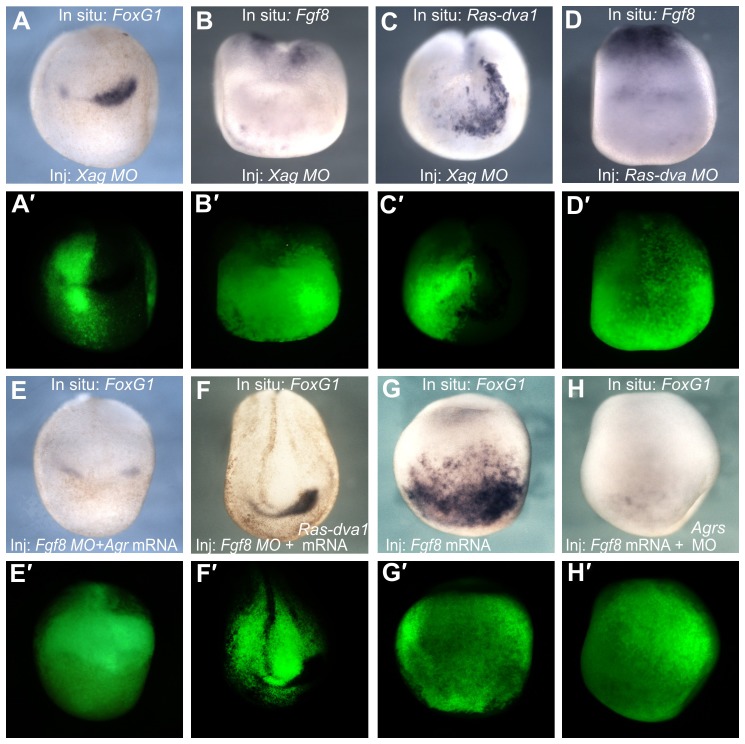

Because downregulation of Agrs caused a reduction in the forebrain structures, one may suppose that this effect could be due to the inhibition of some genes that regulate development of these structures. Indeed, the expression of the telencephalic regulators FoxG1 and Fgf8 was reduced in midneurula stage embryos injected with Xag MO (34/37 and 32/37) (Fig. 6A,B). Interestingly, inhibition of Ras-dva1 expression was also observed in these embryos (30/36) (Fig. 6C). Given that downregulation of Ras-dva1 inhibited Agr expression (Fig. 3), this result indicates a regulatory feedback loop between Ras-dva1 and Agrs.

Fig. 6. Agrs, Fgf8 and Ras-dva1 regulate expression of each other.

(A–C) Injections of Xag and Xagr2 MO elicit inhibition of FoxG1, Fgf8 and Ras-dva1 expression in the anterior ectoderm of midneurula embryos. (D) Injections of Ras-dva MO elicit inhibition of Fgf8 expression in the anterior ectoderm of midneurula embryos. (E,F) Co-injection of Agr mRNA (equimolar mixture of Xag1, Xag2, Xagr2A and Xagr2B mRNAs) or Ras-dva1 mRNA is unable to prevent the inhibitory influence of Fgf8 MO on FoxG1 expression. (G) Injection of Fgf8a mRNA elicits massive ectopic expression of FoxG1 in the anterior ectoderm. (H) Induction of FoxG1 expression elicited by ectopic Fgf8a is suppressed by co-injection of Agrs MO (a mixture of Xag and Xagr2 MO). (A′–H′) Fluorescent image of the embryo shown in panels A–H demonstrates the distribution of injected cells labeled by the co-injected FLD tracer.

Speculating on a possible mechanism of such a feedback loop, one may suppose that one of its important components could be Fgf8, because it is upregulated by Agrs and since its activity is critical for the expression of Ras-dva1. If so, one may predict that the inhibition of Ras-dva1 functioning should result in downregulation of the Fgf8 expression. Indeed, we observed just this effect in embryos microinjected with Ras-dva1 MO (Fig. 6D).

Given that Agrs stimulate FoxG1 expression, which in turn is upregulated by Fgf8 signaling (Danesin and Houart, 2012), one may suppose that the observed downregulation of FoxG1 in embryos with inhibited Agrs could be caused by cessation of Fgf8 expression in the ANB cells. In addition, Agrs might influence FoxG1 expression directly. However, no rescue of the FoxG1 abnormal phenotype generated by the Fgf8 MO was observed in embryos co-injected with mRNA Agrs (2/37) or Ras-dva1 (0/24) (Fig. 6E,F). Therefore, we concluded that Agrs upregulate FoxG1 expression via stimulation of Fgf8 expression.

As we have shown previously, an inhibition of Ras-dva1 translation can interrupt upregulation of FoxG1 expression by the ectopic Fgf8a (Tereshina et al., 2006). Together with the data described above, this result indirectly indicates that besides its stimulating influence on Fgf8 expression, Agrs might be important for the functioning of the Fgf8 signaling per se. In that case one may predict that downregulation of Agrs, similarly to the inhibition of Ras-dva1, will interrupt the Fgf8a-stimulated induction of the FoxG1 expression. Indeed, we observed just this effect when Fgf8a mRNA was co-injected with Agrs MO (44/46) (Fig. 6G,H).

Ras-dva1-mediated Fgf8 signaling induces expression of Agrs through upregulation of Otx2

We have shown previously that the homeodomain transcription factor Otx2 can directly activate the expression of Ras-dva1, while the activity of Ras-dva1 in turn is essential for the expression of Otx2 (Tereshina et al., 2006). Given that Otx2 is also an activator of Agrs expression (Ermakova et al., 1999; Gammill and Sive, 1997; Gammill and Sive, 2000), one may suppose that Ras-dva1-mediated Fgf8 signaling induces expression of Agrs by upregulating Otx2.

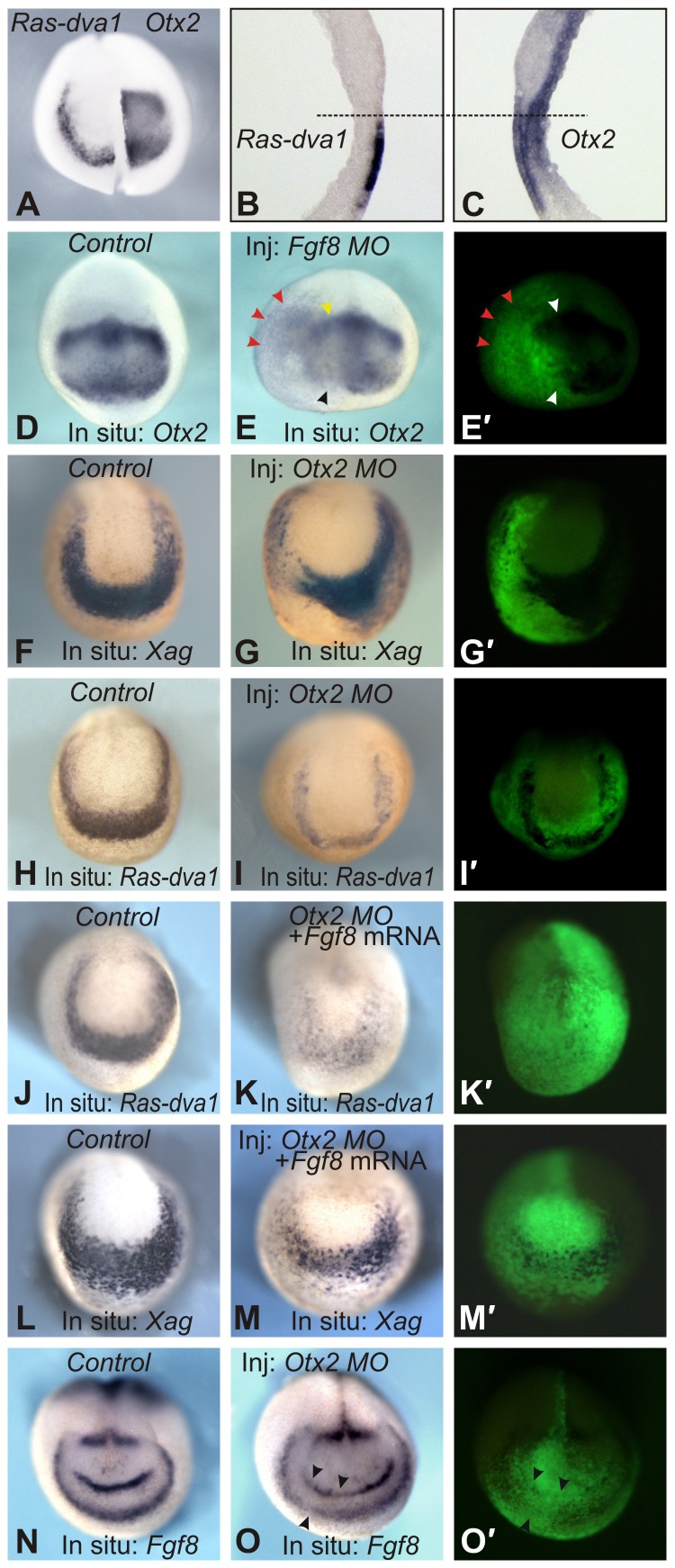

To verify this, we first analyzed the expression pattern of Otx2 in embryonic sections and confirmed that this gene is indeed co-expressed with Ras-dva1 and Agrs in cells in the outer layer of the anterior ectoderm (compare Fig. 7A–C with Fig. 2C1–C4). Furthermore, to test whether endogenous Fgf8 signaling is essential for Otx2 expression, we injected embryos with an Fgf8 MO. As a result, a reduction in Otx2 expression was observed in regions where this gene is expressed most intensely in normal development, i.e. in cells of the presumptive cement gland (27/34) and mesencephalon (23/34) (Fig. 7D,E, black arrowheads). However, the reduction in Otx2 expression was not complete and a low level of expression was still observed in all cases examined. In addition, a characteristic feature of embryos injected with the Fgf8 MO was a posterior and lateral expansion of the low level of Otx2 expression (Fig. 7E, red arrowheads). This result indicates that Fgf8 activity is essential both for the enhancement of Otx2 expression in cells in the presumptive midbrain and cement gland and for restricting expression within these domains. Consistently, at later stages, the inhibition of Otx2 expression in embryos injected with an Fgf8 MO correlated with a reduction in the cement gland (17/30) and forebrain (24/30), i.e. anatomical structures whose development is controlled by Otx2 (supplementary material Fig. S4A,B). Notably, similar abnormalities were seen in embryos injected with Agr (20/32 and 26/32) or Ras-dva1 (17/27 and 24/27) MOs (supplementary material Fig. S4C,D and data not shown).

Fig. 7. Ras-dva1-mediated Fgf8 signaling induces expression of Agrs by upregulating Otx2.

(A–C) Otx2 is co-expressed with Ras-dva1 in cells of the outer layer of the anterior ectoderm. In situ hybridization on the left and right halves of the entire midneurula embryo and on sagittal vibratome sections was performed as described in the legends to Figs 1 and 2. (D,E) Inhibition of Fgf8 mRNA translation by an Fgf8 MO elicits partial inhibition of Otx2 expression and lateral and posterior expansion of the expression domain (red arrowheads). Yellow and black arrowheads indicate a reduction of high Otx2 expression in the presumptive midbrain and cement gland, respectively. (F,G,H,I) Inhibition of Otx2 mRNA translation by an Otx2 MO inhibits Xag and Ras-dva1 expression. (J,K,L,M) Co-injection of Fgf8a mRNA is unable to prevent the inhibitory influence of the Otx2 MO on Xag and Ras-dva1 expression. (N,O) Inhibition of Otx2 mRNA translation by the Otx2 MO inhibits Fgf8 expression (black arrows). (E′,G′,I′,K′,M′,O′) Fluorescent images of embryos shown in panels E,G,I,K,M,O demonstrate distribution of injected cells labeled by the co-injected FLD tracer.

Interestingly, inhibition of Otx2 expression accompanied by expansion of the low expression domains was also characteristic for embryos injected with Fgf8a RNA (24/32) (supplementary material Fig. S4E,F). However, in contrast to the embryos injected with the Fgf8 MO, the Fgf8a mRNA injected embryos demonstrated an expanded area of low Otx2 expression and stripe-like zones of enhanced expression at the periphery of the injected territories (15/32) (supplementary material Fig. S4E,F, arrowheads). Given that Otx2 is the transcriptional activator of Agrs and Ras-dva1, this result is consistent with our data demonstrating that the last two genes were also strongly expressed at the periphery of cell clones bearing the exogenous Fgf8a mRNA (Fig. 4B,C).

To verify that Otx2 activity is indeed critical for Ras-dva1 and Agr expression by another method, we analyzed expression of these genes in embryos injected with Otx2 MO. As a result, we observed a significant downregulation of both genes in the injected embryos (21/28 and 24/30) (Fig. 7F–I). Importantly, these effects Otx2 MO could not be rescued by co-injection of Fgf8 mRNA (4/27), which, if injected alone, readily induced the expression of Ras-dva1 and Agrs (compare Fig. 4A–C with Fig. 7J–M). Consistently, Otx2 mRNA was able to partially rescue cessation of Xag expression elicited by Fgf8 MO (35/42) (supplementary material Fig. S4G,H). By contrast, Ras-dva1 mRNA could not cause similar effect (0/42) (supplementary material Fig. S4I), which indicates the necessity of Fgf8 signaling for the Ras-dva1 activity. In turn, an essential role of Fgf8 for the FoxG1 expression is demonstrated by the fact that neither Ras-dva1, nor Otx2 mRNA were able to rescue FoxG1 expression when these mRNA were co-injected with Fgf8 MO (0/35 and 0/32, respectively) (Fig. 6F; supplementary material Fig. S4J,K).

At the same time, we found that Otx2 activity is important for maintaining Fgf8 expression as a reduction in expression was observed in embryos injected with an Otx2 MO (17/25) (Fig. 7N,O). This result confirms the participation of Otx2 in the signaling feedback loop between ANB cells and the adjacent anterior non-neural ectoderm.

DISCUSSION

Ras-dva1 regulates propagation of Fgf8 signaling in cells in the outer layer of the anterior non-neural ectoderm

As we have shown previously, small GTPase Ras-dva1 controls the telencephalic development in Xenopus laevis embryos by regulating propagation of Fgf8 signaling produced by ANB cells (Tereshina et al., 2006). The following data obtained in the present work confirm the non-autonomous character of this mechanism and demonstrate that it is based on an exchange of Fgf8 and Agrs signals between the neural and non-neural compartments at the ANB.

First, Ras-dva1 is expressed exclusively in cells in the outer layer of the non-neural ectoderm bordering the ANB and, thus, in principal could not regulate expression of the telencephalic genes in the inner layer by a cell autonomous mechanism. Consistently, targeted downregulation of Ras-dva1 elicits inhibition of expression of FoxG1 and Fgf8 in the telencephalic primordium in the inner layer of the anterior neural plate and reduction of the telencephalon. However, these abnormalities could be eliminated by co-injection of Agr mRNA. Second, blocking endogenous Fgf8 mRNA translation prevents Ras-dva1 and Agrs expression in the adjacent Fgf8-non-expressing cells in the outer layer. In agreement with this, the expression of Ras-dva1 and Agrs can be induced by exogenous Fgf8, and this effect can be interrupted by blocking Ras-dva1 mRNA translation. Third, downregulation of Agrs elicits inhibition of FoxG1 and Fgf8 expression and reduction of the telencephalon, i.e. the effects similar to those elicited by the Ras-dva1 MO. However, neither Xagr, nor Ras-dva1 mRNA were able to prevent inhibition of FoxG1 expression caused by Fgf8 MO. The latter results demonstrate an absolute necessity of Fgf8 for the induction of FoxG1. At the same time, an ability of Agrs MO to interrupt FoxG1 induction by Fgf8a indicates that Agrs, besides their influence upon Fgf8 expression, regulate Fgf8 signaling per se. Finally, the data in our previous (Tereshina et al., 2006) and present studies indicate that Ras-dva1 expression in the outer, non-neural layer of the anterior neural fold is directly upregulated by the transcription factor Otx2. Otx2 also operates as an activator of Agrs, and in turn Otx2 gene expression is activated by Fgf8 signaling transmitted by Ras-dva1 in the non-neural cells adjacent to the ANB (Ermakova et al., 1999; Gammill and Sive, 1997; Gammill and Sive, 2000).

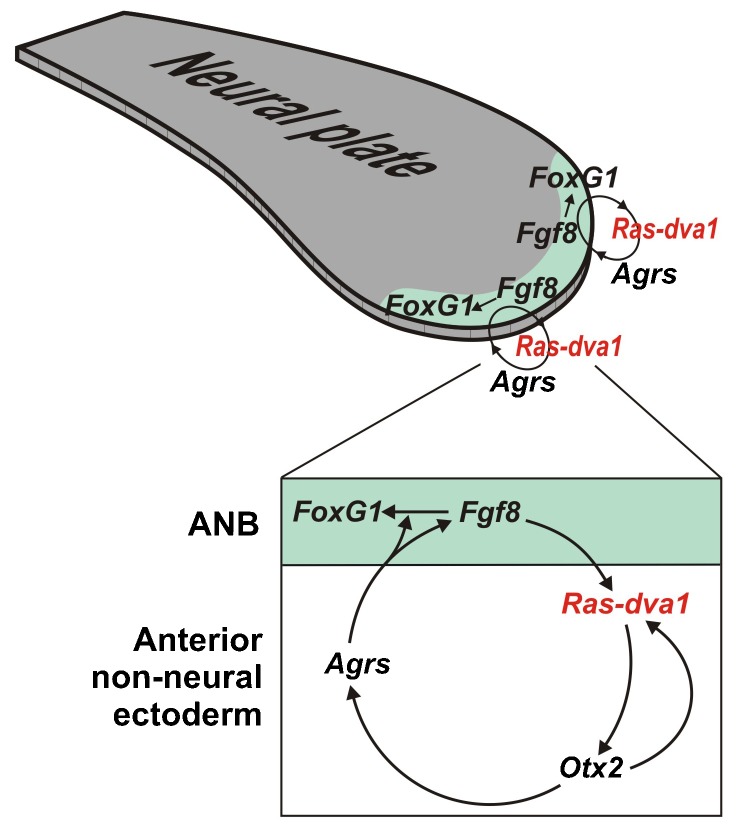

Together all these data suggest a model in which Fgf8 produced by the ANB cells induces Agrs expression in the cells adjacent to the anterior non-neural ectoderm by mediating Ras-dva1 and Otx2. In turn, Agrs secreted by cells in the anterior non-neural ectoderm regulate telencephalic development as through stimulation of Fgf8 expression in the ANB cells, as well as by promotion of Fgf8 signaling per se (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Model for the Fgf8- and Agrs-based signal exchange between neural and non-neural cells at the anterior neural plate border.

Fgf8 produced by the ANB cells induces the expression of Agrs in cells adjacent to the anterior non-neural ectoderm by mediating Ras-dva1 and Otx2. In turn, Agrs secreted by cells in the anterior non-neural ectoderm promote forebrain development through stimulation of both Fgf8 gene expression and Fgf8 protein signaling in the ANB cells.

The importance of ANB as a signaling center that regulates patterning of the rostral forebrain rudiment has been studied thoroughly in zebrafish and mice (Cavodeassi and Houart, 2012; Houart et al., 2002; Houart et al., 1998). However, the role of possible signal exchanges between cells in the ANB and the adjacent non-neural ectoderm was not studied. To our knowledge, only data on the role of BMP signals generated by cells of the non-neural ectoderm and regulating the anterior neural plate patterning have been published (Barth et al., 1999; Houart et al., 2002; Shimogori et al., 2004). Our finding, which demonstrates that the pattern of Agr secreted proteins is necessary, is another example of such a signal produced by cells in the non-neural ectoderm.

Agrs control both forebrain development and body appendage regeneration

We demonstrate here that the activities of Xag1/Xag2 and Xagr2A/Xagr2B promote expression of at least two ANB regulators, Fgf8 and FoxG1, and are necessary for forebrain development. These results are consistent with the data from other authors, who showed that ectopic Xag2 was able to induce several anterior markers in the embryonic ectoderm (Aberger et al., 1998). On the other hand, the newt Xagr2A/Xagr2B homolog was reported to be a key player during limb regeneration in adult salamanders (Kumar et al., 2007). In agreement with this, we have recently demonstrated that Xag1/2 and Xagr2A/Xagr2B are involved in the regeneration of the tail and hindlimb bud in Xenopus laevis tadpoles (Ivanova et al., 2013).

Given these data, an important future study is to compare the molecular mechanisms that regulate Agrs expression during body appendage regeneration and forebrain development. In particular, an area of interest for these studies is whether Fgf8, which participates in both these processes (Christen and Slack, 1997), might also be involved in regulating Agrs expression during tail and limb bud regeneration in Xenopus tadpoles. Furthermore, given that Ras-dva1 was shown to be involved in Agrs induction by Fgf8 in the anterior non-neural ectoderm, an important question is whether this small GTPase plays the same role during the regeneration of body appendages.

Another critical issue concerns the molecular mechanism of Agrs function. Importantly, evidence suggests that in contrast to other PDIs, Agrs act extracellularly (Kumar et al., 2011; Vanderlaag et al., 2010). Therefore, one may hypothesize that Agrs by themselves might play a role as signaling factors that interact with some as-yet unidentified receptors in cells of the inner layer. In particular, during regeneration of the salamander limb bud, Agr2 homolog regulates the expression of regenerating blastema-specific genes via binds to the membrane-anchored receptor Prod1 (Blassberg et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2007).

Alternatively, as Agrs belong to the superfamily of protein disulfide isomerases (PDI), which modulate folding of other proteins (Hatahet and Ruddock, 2009; Persson et al., 2005), they might regulate the folding of some extracellular proteins in the intercellular space. Such a supposition is supported by our data demonstrating ability of Agrs to regulate Fgf8 signaling per se, besides influencing Fgf8 expression. Accordingly, one may further suppose that by this way Agrs might regulate folding of Fgf8, or/and its receptor(s), or/and their co-factors.

An important question for further study is to understand which of these molecular mechanisms is implemented during forebrain development and body appendage regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Gerald Eagleson for discussion.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.B.T. and G.V.E. designed, conducted and interpreted experiments, A.S.I. participated in some experiments, A.G.Z. generated the overall concept, conducted some experiments, designed and interpreted experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by a MCB RAS grant, RFBR grants [N 09-04-00452, 12-04-33111, 12-04-31537, 13-04-01516, 13-04-40194-KOMFI] and a grant from the Dynasty Foundation to M.B.T.

References

- Aberger F., Weidinger G., Grunz H., Richter K. (1998). Anterior specification of embryonic ectoderm: the role of the Xenopus cement gland-specific gene XAG-2. Mech. Dev. 72, 115–130 10.1016/S0925--4773(98)00021--5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth K. A., Kishimoto Y., Rohr K. B., Seydler C., Schulte-Merker S., Wilson S. W. (1999). Bmp activity establishes a gradient of positional information throughout the entire neural plate. Development 126, 4977–4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayramov A. V., Eroshkin F. M., Martynova N. Y., Ermakova G. V., Solovieva E. A., Zaraisky A. G. (2011). Novel functions of Noggin proteins: inhibition of Activin/Nodal and Wnt signaling. Development 138, 5345–5356 10.1242/dev.068908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blassberg R. A., Garza-Garcia A., Janmohamed A., Gates P. B., Brockes J. P. (2011). Functional convergence of signalling by GPI-anchored and anchorless forms of a salamander protein implicated in limb regeneration. J. Cell Sci. 124, 47–56 10.1242/jcs.076331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carron C., Bourdelas A., Li H. Y., Boucaut J. C., Shi D. L. (2005). Antagonistic interaction between IGF and Wnt/JNK signaling in convergent extension in Xenopus embryo. Mech. Dev. 122, 1234–1247 10.1016/j.mod.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavodeassi F., Houart C. (2012). Brain regionalization: of signaling centers and boundaries. Dev. Neurobiol. 72, 218–233 10.1002/dneu.20938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen B., Slack J. M. (1997). FGF-8 is associated with anteroposterior patterning and limb regeneration in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 192, 455–466 10.1006/dbio.1997.8732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesin C., Houart C. (2012). A Fox stops the Wnt: implications for forebrain development and diseases. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 323–330 10.1016/j.gde.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleson G. W., Harris W. A. (1990). Mapping of the presumptive brain regions in the neural plate of Xenopus laevis. J. Neurobiol. 21, 427–440 10.1002/neu.480210305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleson G. W., Jenks B. G., Van Overbeeke A. P. (1986). The pituitary adrenocorticotropes originate from neural ridge tissue in Xenopus laevis. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 95, 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleson G., Ferreiro B., Harris W. A. (1995). Fate of the anterior neural ridge and the morphogenesis of the Xenopus forebrain. J. Neurobiol. 28, 146–158 10.1002/neu.480280203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermakova G. V., Alexandrova E. M., Kazanskaya O. V., Vasiliev O. L., Smith M. W., Zaraisky A. G. (1999). The homeobox gene, Xanf-1, can control both neural differentiation and patterning in the presumptive anterior neurectoderm of the Xenopus laevis embryo. Development 126, 4513–4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermakova G. V., Solovieva E. A., Martynova N. Y., Zaraisky A. G. (2007). The homeodomain factor Xanf represses expression of genes in the presumptive rostral forebrain that specify more caudal brain regions. Dev. Biol. 307, 483–497 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R. B., Baker J. C., Harland R. M. (2006). FGF8 spliceforms mediate early mesoderm and posterior neural tissue formation in Xenopus. Development 133, 1703–1714 10.1242/dev.02342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill L. S., Sive H. (1997). Identification of otx2 target genes and restrictions in ectodermal competence during Xenopus cement gland formation. Development 124, 471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill L. S., Sive H. (2000). Coincidence of otx2 and BMP4 signaling correlates with Xenopus cement gland formation. Mech. Dev. 92, 217–226 10.1016/S0925--4773(99)00342--1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland R. M. (1991). In situ hybridization: an improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 36, 685–695 10.1016/S0091--679X(08)60307--6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatahet F., Ruddock L. W. (2009). Protein disulfide isomerase: a critical evaluation of its function in disulfide bond formation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2807–2850 10.1089/ars.2009.2466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houart C., Westerfield M., Wilson S. W. (1998). A small population of anterior cells patterns the forebrain during zebrafish gastrulation. Nature 391, 788–792 10.1038/35853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houart C., Caneparo L., Heisenberg C., Barth K., Take-Uchi M., Wilson S. (2002). Establishment of the telencephalon during gastrulation by local antagonism of Wnt signaling. Neuron 35, 255–265 10.1016/S0896--6273(02)00751--1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyenne V., Louvet-Vallée S., El-Amraoui A., Petit C., Maro B., Simmler M. C. (2005). Vezatin, a protein associated to adherens junctions, is required for mouse blastocyst morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 287, 180–191 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova A. S., Tereshina M. B., Ermakova G. V., Belousov V. V., Zaraisky A. G. (2013). Agr genes, missing in amniotes, are involved in the body appendages regeneration in frog tadpoles. Sci. Rep 3, 1279 10.1038/srep01279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Godwin J. W., Gates P. B., Garza-Garcia A. A., Brockes J. P. (2007). Molecular basis for the nerve dependence of limb regeneration in an adult vertebrate. Science 318, 772–777 10.1126/science.1147710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Delgado J. P., Gates P. B., Neville G., Forge A., Brockes J. P. (2011). The aneurogenic limb identifies developmental cell interactions underlying vertebrate limb regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13588–13593 10.1073/pnas.1108472108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynova N., Eroshkin F., Ermakova G., Bayramov A., Gray J., Grainger R., Zaraisky A. (2004). Patterning the forebrain: FoxA4a/Pintallavis and Xvent2 determine the posterior limit of Xanf1 expression in the neural plate. Development 131, 2329–2338 10.1242/dev.01133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz M. V., Fradkov A. F., Labas Y. A., Savitsky A. P., Zaraisky A. G., Markelov M. L., Lukyanov S. A. (1999). Fluorescent proteins from nonbioluminescent Anthozoa species. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 969–973 10.1038/13657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov V. V., Alexandrova E. M., Ermakova G. V., Zaraisky A. G. (2003). Expression zones of three novel genes abut the developing anterior neural plate of Xenopus embryo. Gene Expr. Patterns 3, 225–230 10.1016/S1567--133X(02)00077--7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offield M. F., Hirsch N., Grainger R. M. (2000). The development of Xenopus tropicalis transgenic lines and their use in studying lens developmental timing in living embryos. Development 127, 1789–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S., Rosenquist M., Knoblach B., Khosravi-Far R., Sommarin M., Michalak M. (2005). Diversity of the protein disulfide isomerase family: identification of breast tumor induced Hag2 and Hag3 as novel members of the protein family. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 36, 734–740 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serebrovskaya E. O., Gorodnicheva T. V., Ermakova G. V., Solovieva E. A., Sharonov G. V., Zagaynova E. V., Chudakov D. M., Lukyanov S., Zaraisky A. G., Lukyanov K. A. (2011). Light-induced blockage of cell division with a chromatin-targeted phototoxic fluorescent protein. Biochem. J. 435, 65–71 10.1042/BJ20101217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimogori T., Banuchi V., Ng H. Y., Strauss J. B., Grove E. A. (2004). Embryonic signaling centers expressing BMP, WNT and FGF proteins interact to pattern the cerebral cortex. Development 131, 5639–5647 10.1242/dev.01428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tereshina M. B., Zaraisky A. G., Novoselov V. V. (2006). Ras-dva, a member of novel family of small GTPases, is required for the anterior ectoderm patterning in the Xenopus laevis embryo. Development 133, 485–494 10.1242/dev.02207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tereshina M. B., Belousov V. V., Zaraĭskiĭ A. G. (2007). [Study of the mechanism of Ras-dva small GTPase intracellular localization]. Bioorg. Khim. 33, 574–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlaag K. E., Hudak S., Bald L., Fayadat-Dilman L., Sathe M., Grein J., Janatpour M. J. (2010). Anterior gradient-2 plays a critical role in breast cancer cell growth and survival by modulating cyclin D1, estrogen receptor-alpha and survivin. Breast Cancer Res. 12, R32 10.1186/bcr2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.