Abstract

Background:

Early enamel lesions have a potential to re-mineralize and prevent caries progress.

Aim:

The aim of the following study is to determine the depth of penetration of low viscosity resin into artificially created enamel lesions.

Materials and Methods:

A sample of 20 sound premolars, indicated for orthodontic extraction, formed the study group. The teeth were coated with a nail varnish, leaving a window of 4 mm × 4 mm, on buccal surfaces of sound, intact enamel. Each tooth was subsequently immersed in demineralizing solution for 4 days to produce artificial enamel lesions. The demineralized area was then infiltrated with low viscosity resin (Icon Infiltrant, DMG, Hamburg, Germany) as per the manufacturer's instructions. All the restored teeth were then immersed in methylene blue dye for 24 h at 37°C. Teeth were then sectioned longitudinally through the lesion into two halves. The sections were observed under stereomicroscope at ×80 magnification and depth of penetration of the material was measured quantitatively using Motic software.

Results:

The maximum depth of penetration of the resin material was 6.06 ± 3.31 μm.

Conclusions:

Resin infiltration technique appears to be effective in sealing enamel lesions and has great potential for arresting white spot lesions.

Keywords: Caries, dental white spots, resins

INTRODUCTION

White spot lesions are early signs of demineralization under intact enamel, which may or may not lead to the development of caries. White spot lesions occur when the pathogenic bacteria have breached the enamel layer and organic acids produced by the bacteria have leached out a certain amount of calcium and phosphate ions that may or may not be replaced naturally by the remineralization process. This loss of mineralized layer creates porosities that change the refractive index (RI) of enamel that is usually translucent.[1] The causes of white spot lesions may include plaque accumulation particularly along the cervical margins of teeth, inadequate home oral care, consumption of diets rich in sugar and/or those that frequently lower the intraoral pH. White spot lesions may also be seen after removal of orthodontic bands and brackets.

The progression of white spot lesions can be slowed or even arrested by non-operative measures that influence etiologic factors such as maintaining oral hygiene and use of remineralizing agents such as topical fluorides and casein phospho peptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. Although lesions can be arrested by these measures they still continue to pose esthetic problems referred to as “enamel scars”.[2] At times they may not be effective and the carious lesions tend to progress. In such conditions, the infiltration of caries lesions with low viscosity light curing resins is considered as a treatment option for non cavitated lesions, which are not expected to arrest or remineralize.[3]

Caries infiltration is a novel treatment option for white spot lesions and might bridge the gap between non-operative and operative modalities. It is a micro-invasive technology that fills, reinforces and stabilizes demineralized enamel, without drilling or sacrificing healthy tooth structure. It has also been shown to inhibit caries progression in lesions that are too advanced for fluoride therapy.

Caries infiltration involves the use of low-viscosity light curing resins composed of triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) which completely fills pores within the tooth, replacing lost tooth structure and stopping caries progression.[4,5] It penetrates into the lesion by capillary forces and creates a diffusion barrier inside the lesion and not only on the lesion surface.[6,7] The use of 15% hydrochloric acid for etching the surface layer is effective and postulated to be beneficial for a deeper infiltration of the resin into the body of the lesion.[8] The use of solvents such as ethanol, acetone and water in resin infiltrates show lower surface tension and viscosities compared with materials without solvents. These materials show higher penetration coefficient.[9] Thus, the success of caries infiltration technique, depends on the efficacy of this low viscosity resin or “caries infiltrant” to penetrate up to the depth of the white spot lesion and not just mask the lesion.

Studies which have assessed the caries infiltrate, have shown that resin infiltration of initial non-cavitated proximal lesions have a good clinical applicability and very high patient acceptance.[7,10,11] A study by Wiegand et al. showed that use of caries infiltrate before application of conventional adhesive does not impair bonding to sound and demineralized enamel and can be used as a pre-treatment in demineralized enamel.[3] However, a study by Schmidlin et al. showed that application of an adhesive, either alone or in combination with the caries infiltrant, is more effective to protect enamel dissolution than application of only the infiltrant.[12]

Although clinical studies have been done earlier,[4,5,6,7,9,10] they focused mainly on the clinical success and outcome of the resin. Depth of resin penetration could be a key determining factor for the creation of a diffusion barrier and the success of infiltration. Hence, the aim of the present study was to determine the depth of penetration of a commercially available resin infiltrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present in-vitro study was conducted in the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry and Department of Oral Pathology. The study sample consisted of 20 healthy, sound premolars, indicated for orthodontic extraction. The teeth were collected and stored in thymol solution until the study was conducted. On the day of study, the teeth samples were removed from the solution, washed and dried for use. All teeth samples were coated with a nail varnish, leaving a 4 mm × 4 mm window on the buccal surface. A demineralizing solution was prepared (2.2 mM calcium chloride, 2.2 mM monopotassium phosphate, 0.05 mM acetic acid having pH adjusted to 4.4 and 1M potassium hydroxide) and all the samples were immersed in this demineralizing solution for 4 days to create artificial white spot lesions.[13] After 4 days, the teeth were removed from the solution and the demineralized window of enamel was infiltrated with the low viscosity resin (ICON-DMG, Hambergh, Germany) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Method of application of low viscosity resin (ICON-DMG)™

The surface of the artificially created white spot was etched using 15% hydrochloric acid gel (Icon etch™) for 2 min. The gel was stirred from time to time during application with a microbrush. Subsequently, the etching gel was thoroughly washed for 30 s using a water spray. Following etching the lesion was desiccated by applying ethanol (Icon-Dry™) for 30 s and air dried. Low viscosity resin was applied on the lesion surface using a microbrush and was allowed to penetrate for 3 min. The excess material was removed using a cotton roll and the surface was light cured for 40 s (LEDition, Ivoclaire, Vivadent). The application of infiltrant was repeated to minimize enamel porosity.

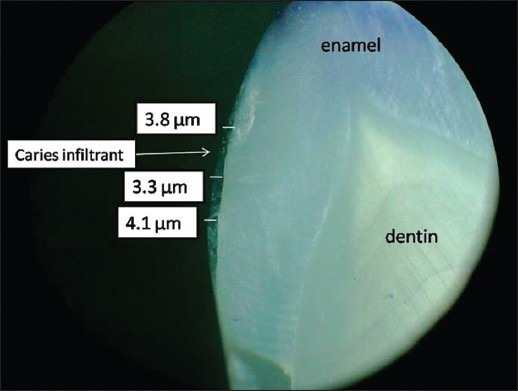

The samples were immersed in methylene blue dye for 24 h at 37°C and sectioned into two halves along the bucco lingual plane with a diamond disc mounted on a low speed handpiece. All the 40 specimens, which included the mesial and distal halves of all the 20 samples, were then observed under the stereomicroscope at ×80 magnification for determining the depth of penetration of the low viscosity resin. Stereomicroscopic photographs were taken and using Motic software the depth of penetration of infiltrant was measured in microns [Figures 1]. The measurements were made on three different locations and the maximum and minimum value was considered.

Figure 1.

Maximum and minimum depth of penetration of caries infiltrant

RESULTS

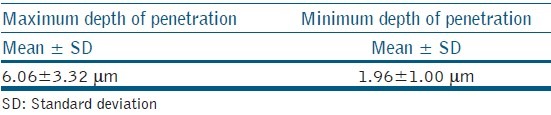

The mean values obtained for maximum depth of penetration of the caries infiltrant material was 6.06 ± 3.32 μm and for minimum depth of penetration, it was 1.96 ± 1.00 μm [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean values of depth of penetration of caries infiltrant

DISCUSSION

The treatment of white spot or non cavitated lesions should aim to arrest the lesion progression and improve the aesthetics by diminishing the opacity.[14,15] Caries infiltration acts by arresting the lesion progression by occluding the microporosities that provide diffusion pathways for acids and dissolved minerals.[16] It is a simple, painless, ultraconservative technique that allows immediate treatment of lesions, not advanced enough for restorative therapy.

Infiltrants used in this technique are light curable resins that are optimized for rapid penetration into the capillary structures of the lesion body. These materials exhibit a very low viscosity, low contact angles to the enamel and high surface tension. These properties are important for complete depth of penetration of the resin infiltrant into the body of the enamel lesions.[17]

The partially mineralized intact surface layer could hamper the resin from penetrating into the lesion. Hence, this layer was removed by acid etching with 15% hydrochloric acid gel. Application of hydrochloric acid as an etchant has been demonstrated to be superior to 37% phosphoric acid gel in removing the surface layer of natural enamel lesions when applied for 120 s.[18] The etching procedure removes superficial discolorations and the higher mineralized surface layer, which might hamper resin penetration. Hydrochloric acid in similar concentrations is widely accepted in aesthetic dentistry to remove superficial discolorations using enamel microabrasion. However, contact with soft-tissues may cause ulcerations if used for more than 30 s. Therefore, in clinical application, isolation with a rubber dam is mandatory.[8]

Sound enamel has a RI of 1.62, while the micro porosities of enamel lesions are filled with either a watery medium (RI: 1.33) or air (RI: 1.0). The difference in refractive indices between the enamel crystals and medium inside the porosities causes light scattering that results in a whitish opaque appearance of these lesions, especially when they are desiccated.[1]

The principle of masking enamel lesions by resin infiltration is based on changes in light scattering within the lesions. This novel technique involves infiltration of the carious lesions with resin (RI 1.46) that, in contrast to the watery medium, cannot evaporate. Therefore, the difference in refractive indices between porosities and enamel is negligible and lesions appear similar to that of the surrounding sound enamel.[15] It has a chameleon effect and requires no shade matching. Lesions lose their whitish opaque color and blend reasonably well with the surrounding natural tooth structure. An immediate improvement in the aesthetic appearance is observed.

Since many enamel lesions remain unchanged or progress very slowly over long periods, there is adequate time to assess caries risk and initiate preventive procedures. Furthermore, the percentage of radiographically visible proximal lesions in the outer half of dentin that are cavitated has declined over the past several decades to approximately 41%.[19] The efficacy of caries infiltration has been shown to be limited when used in cavitated lesions.[20]

In our study, the infiltrant successfully penetrated into the artificially created white spot lesion and formed a homogenous resin layer. These findings were in accordance with earlier observations which reported that resin mixtures with high TEGDMA concentrations tend to show better inhibition of lesion progression than those with high concentration of bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate. It was attributed to enhanced ability of the resin to penetrate after application of ethanol.[21]

The mean values observed in this study are similar to those obtained by Buonocore,[22] Voss and Charbeneau[23](5-10 μm) and Pahlavan et al.[24](7 μm) but lower than those reported by Wickwire and Rentz[25](25 μm) and Arakawa et al.[26](50 μm). These studies were based on indirect decalcification procedures to assess the depth of penetration.

Wetting and penetration of resins might have been impaired as contamination of enamel surface with traces of dust, water and organic substances could not be avoided. A proper decontamination of the lesion may be essential to determine complete resin penetration. In the oral cavity, the enamel lesions are exposed to several contaminants, which tend to reduce the surface energy of enamel.[9] Other factors such as saliva, pellicle and intraoral pH may also influence the depth of penetration of the infiltrate.

Lesser filler loading contributes to low viscosity and enables better penetrability.[27] The low viscosity of the infiltrant, enables it to be applied even on tooth surfaces which are difficult to access, such as, interproximal surfaces. Recently, it was shown that caries infiltration reduced lesion progression of non-cavitated interproximal caries lesions extending radiographically into the inner half of enamel up to the outer third of dentin.[28] Microinvasive technology can be an advantage in the pediatric population. The use of caries infiltration limits the use of dental drill, thus improving patient acceptance to treatment. It also avoids periodic recall of the patient compared with fluoride application as it is a single sitting procedure. This new technology allows for specific therapy of early carious lesions without the need to prepare cavities, thus protecting and fully preserving the hard tissue surrounding the lesion. Furthermore, it is virtually painless as it requires no anesthesia and the treatment duration is predictable, thus positively affect the compliance of young patients.

Caries infiltration can also be used as an adjunctive therapeutic measure for white spot lesions in adolescents and adults following fixed orthodontic therapy and in the absence of good oral hygiene.[29]

CONCLUSION

The maximum depth of penetration of the resin material was 6.06 ± 3.32 μm. Caries infiltration can be used as a painless and effective option for treating white spot lesions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kidd EA, Fejerskov O. What constitutes dental caries. Histopathology of carious enamel and dentin related to the action of cariogenic biofilms? J Dent Res. 2004;83(Spec No C):C35–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammad SM, El Banna M, El Zayat I, Mohsen MA. Effect of resin infiltration on white spot lesions after debonding orthodontic brackets. Am J Dent. 2012;25:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiegand A, Stawarczyk B, Kolakovic M, Hämmerle CH, Attin T, Schmidlin PR. Adhesive performance of a caries infiltrant on sound and demineralised enamel. J Dent. 2011;39:117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller J, Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Kielbassa AM. Inhibition of lesion progression by the penetration of resins in vitro: Influence of the application procedure. Oper Dent. 2006;31:338–45. doi: 10.2341/05-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H. Inhibition of caries progression by resin infiltration in situ. Caries Res. 2010;44:47–54. doi: 10.1159/000275917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H, Kielbassa AM. Resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2007;86:662–6. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S. Improved resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2008;87:1112–6. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paris S, Dörfer CE, Meyer-Lueckel H. Surface conditioning of natural enamel caries lesions in deciduous teeth in preparation for resin infiltration. J Dent. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H, Cölfen H, Kielbassa AM. Penetration coefficients of commercially available and experimental composites intended to infiltrate enamel carious lesions. Dent Mater. 2007;23:742–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altarabulsi MB, Alkilzy M, Splieth CH. Clinical applicability of resin infiltration for proximal caries. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:97–104. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a28934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martignon S, Ekstrand KR, Gomez J, Lara JS, Cortes A. Infiltrating/sealing proximal caries lesions: A 3-year randomized clinical trial. J Dent Res. 2012;91:288–92. doi: 10.1177/0022034511435328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidlin PR, Sener B, Attin T, Wiegand A. Protection of sound enamel and artificial enamel lesions against demineralisation: Caries infiltrant versus adhesive. J Dent. 2012;40:851–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar VL, Itthagarun A, King NM. The effect of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate on remineralization of artificial caries-like lesions: An in vitro study. Aust Dent J. 2008;53:34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sapir S, Shapira J. Clinical solutions for developmental defects of enamel and dentin in children. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29:330–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H. Masking of labial enamel white spot lesions by resin infiltration - A clinical report. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:713–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S. Progression of artificial enamel caries lesions after infiltration with experimental light curing resins. Caries Res. 2008;42:117–24. doi: 10.1159/000118631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gugnani N, Pandit IK, Gupta M, Josan R. Caries infiltration of noncavitated white spot lesions: A novel approach for immediate esthetic improvement. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:S199–202. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S, Kielbassa AM. Surface layer erosion of natural caries lesions with phosphoric and hydrochloric acid gels in preparation for resin infiltration. Caries Res. 2007;41:223–30. doi: 10.1159/000099323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitts NB, Rimmer PA. An in vivo comparison of radiographic and directly assessed clinical caries status of posterior approximal surfaces in primary and permanent teeth. Caries Res. 1992;26:146–52. doi: 10.1159/000261500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paris S, Bitter K, Naumann M, Dörfer CE, Meyer-Lueckel H. Resin infiltration of proximal caries lesions differing in ICDAS codes. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119:182–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson C. Filling without drilling. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1261–3. doi: 10.1177/0022034511418827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buonocore MG. A simple method of increasing the adhesion of acrylic filling materials to enamel surfaces. J Dent Res. 1955;34:849–53. doi: 10.1177/00220345550340060801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voss JE, Charbeneau GT. A scanning electron microscope comparison of three methods of bonding resin to enamel rod ends and longitudinally cut enamel. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;98:384–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pahlavan A, Dennison JB, Charbeneau GT. Penetration of restorative resins into acid-etched human enamel. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976;93:1170–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1976.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickwire NA, Rentz D. Enamel pretreatment: A critical variable in direct bonding systems. Am J Orthod. 1973;64:499–512. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(73)90263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arakawa Y, Takahashi Y, Sebata M. The effect of acid etching on the cervical region of the buccal surface of the human premolar, with special reference to direct bonding techniques. Am J Orthod. 1979;76:201–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(79)90121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandes KS, Chalakkal P, de Ataide Ide N, Pavaskar R, Fernandes PP, Soni H. A comparison between three different pit and fissure sealants with regard to marginal integrity. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:146–50. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.94588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Meyer-Lueckel H. Resin infiltration of caries lesions: An efficacy randomized trial. J Dent Res. 2010;89:823–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034510369289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shivanna V, Shivakumar B. Novel treatment of white spot lesions: A report of two cases. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14:423–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.87217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]