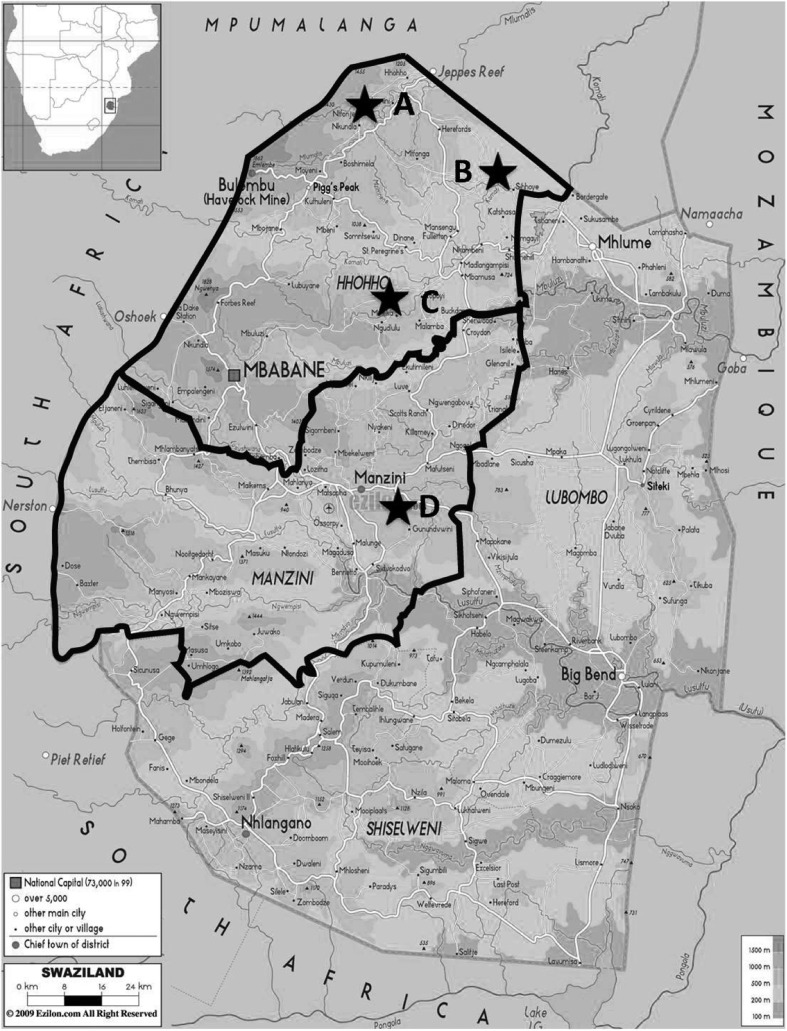

Intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) including helminths and protozoa are estimated to affect around 3.5 billion people globally and 450 million are ill as a result of these infections, the majority being children.1 Several studies have indicated that geohelminth and/or some protozoa infections may result in impairments in physical, intellectual and cognitive development.2 Like other developing countries, IPIs are a major health problem in the Kingdom of Swaziland (KS). This study intends to explore IPIs status of primary schoolchildren living in areas devoid of sanitation in northwestern KS so as to improve Swazi children health. Geographically, KS can be divided into High- (1200 m), Middle- (600 m) and Lowveld (250 m). Participant schoolchildren from four primary schools including three schools located in the High- (school A), Middle- (school B) and Lowveld areas (school C) of the Hhohho Province as well as one school (school D) located in the Lowveld area of the Manzini Province were selected (Fig. 1) after informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians. In total, 267 fresh stool samples (boys: 115 stool samples, girls: 152 stool samples) were obtained for examination of IPIs by using merthiolate-iodine-formalin concentration method.3 Ethical approval (Ref. no. MH 599B) was obtained from the Health Ministry. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software system (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the different biological phenomena of mother-newborn immune interaction which can theoretically affect newborn immune responses to microbial antigens.

The present study found that 32.2% (86/267) of schoolchildren in northwestern KS are infected predominantly by intestinal protozoan parasites, e.g. pathogenic (20.6%, 55/267) and non-pathogenic (11.2%, 30/267) protozoa instead of soil-transmitted helminths (Table 1) and all of these pathogenic protozoa, e.g. amoeba, B. hominis and G. lamblia can cause gastrointestinal illness of varying severity and consequence.4 Polyparasitism, e.g. dual (7.5%, 20/267) and triple infections (2.6%, 7/267) Table 1) particularly on different pathogenic and non-pathogenic protozoan co-infections in KS schoolchildren living in High-, Middle or Lowveld areas is very common, reflecting the very possibility that those schoolchildren lack home sanitation and thus have greater opportunities to contact contaminated soil and infected water when taking care of body hygiene and domestic activities.5 Therefore, key measures would be in improving environmental sanitation to prevent intestinal pathogenic protozoan and helminthic infections but also properly treating infected schoolchildren by considering adding praziquantel and/or metronidazole to mebendazole- or albendazole-alone regular deworming regimens to KS schoolchildren. Diagnostics for IPIs in most of the hospital medical laboratories seemed problematic because all of them used an insensitive direct wet smear method which is unable to detect small-sized helminthic ova and protozoan cysts/trophozoites. This led to low/no detection rates of IPIs in KS schoolchildren. A more sensitive merthiolate-iodine-formalin method was recommended to replace direct wet smear method to be used as the detection system for IPIs in KS to greatly improve the detection rate of IPIs.

Table 1. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among primary schoolchildren in northwestern Kingdom of Swaziland, Southern Africa.

| Subjects | Age | No. of examined | No. of positive (%) | Infection status | Helminth | Protozoan | ||||||||||

| Single (No., %) | Dual (No., %) | Triple (No., %) | Pathogenic* (No., %) | Non-pathogenic† (No., %) | ||||||||||||

| Province | ||||||||||||||||

| Manzini | 10.8±2.5 | 66 | 19 | 28.8§ | 12 | 18.2 | 5 | 7.6 | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 18.2 | 7 | 10.6 |

| Boys | 11.1±2.5 | 25 | 8 | 32.0 | 6 | 24.0 | 2 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 20.0 | 3 | 12.0 |

| Girls | 10.7±2.5 | 41 | 11 | 26.8 | 6 | 54.5 | 3 | 27.3 | 2 | 18.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 17.1 | 4 | 9.7 |

| Hhoho | 10.5±2.6 | 201 | 67 | 33.3§ | 47 | 23.4 | 15 | 7.5 | 5 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 43 | 21.4 | 23 | 11.4 |

| Boys | 1.7±2.9 | 90 | 35 | 38.9 | 26 | 28.9 | 7 | 7.8 | 2 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 27.8 | 10 | 11.1 |

| Girls | 10.5±2.4 | 111 | 32 | 28.8 | 21 | 18.9 | 8 | 7.2 | 3 | 2.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 18 | 16.2 | 13 | 11.7 |

| Altitude | ||||||||||||||||

| Highveld | 11.0±2.7 | 100 | 31 | 31.0** | 28 | 28.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 20 | 20.0 | 10 | 10.0 |

| Middleveld | 9.9±2.2 | 36 | 23 | 63.9¶,** | 12 | 33.4 | 8 | 22.2 | 3 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 41.7 | 8 | 22.2 |

| Lowveld | 10.6±2.6 | 131 | 32 | 24.4¶ | 19 | 14.5 | 10 | 7.6 | 3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 15.3 | 12 | 9.2 |

| Total | 10.6±2.6 | 267 | 86 | 32.2 | 59 | 22.1 | 20 | 7.5 | 7 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 55 | 20.6 | 30 | 11.2 |

| Boys | 10.8±2.8 | 115 | 43 | 37.4‡ | 32 | 27.9 | 9 | 7.8 | 2 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 30 | 26.1 | 13 | 11.3 |

| Girls | 10.5±2.4 | 152 | 43 | 28.3‡ | 27 | 17.8 | 11 | 7.2 | 5 | 3.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 25 | 16.4 | 17 | 11.2 |

*Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica/dispar, Blastocystis hominis.

†Entamoeba coli, Endolimax nana, Chilomastix mesnelli, Iodamoeba bütschlii.

‡odd ratios (ORs) = 1.51, 95 confidential interval (CI) = 0.9–2.5, P = 0.1.

§ORs = 1.2, 95CI = 0.7–2.3, P = 0.5.

¶ORs = 5.5, 95CI = 2.5–12.0, P<0.001.

**ORs = 3.9; 95CI = 1.8–8.8; P<0.001.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Health, Social Welfare, Kingdom of Swaziland. The authors also thank the Embassy of the Republic of China (Taiwan) in Swaziland, the International Cooperation and Development Fund, Taiwan and the Taiwanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well as Taipei Medical University (TMU98-AE1-B19) for their support of this investigation. They are also grateful to Dr Chamberlin for his critical revision and edition of our manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Partners for parasite control: geographical distribution and useful facts and stats. Geneva: WHO, 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/wormcontrol/statistics/geographical/en/index.html (accessed 15 March 2007) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkman DS, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, Lopez SL, Black MM. Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet. 2002;359:564–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07744-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh MH, Lin WY, Dai CY, Huang JF, Huang CK, Chien HH, et al. Intestinal parasitic infection detected by stool examination in foreign laborers in Kaohsiung. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2010;26:136–43. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(10)70020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yakoob J, Jafri W, Beg MA, Abbas Z, Naz S, Islam M, et al. Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis in patients fulfilling irritable bowel syndrome criteria. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:679–84. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinmann P, Utzinger J, Du ZW, Zhou XN. Multiparasitism a neglected reality on global, regional and local scale. Advanced Parasitol. 2010;73:21–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(10)73002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]