Abstract

This paper examines the impact of a community-based intervention on the trends in the uptake of polio vaccination following a community mobilization campaign for polio eradication in northern Nigeria. Uptake of polio vaccination in high-risk communities in this region has been considerably low despite routine and supplemental vaccination activities. Large numbers of children are left unvaccinated because of community misconceptions and distrust regarding the cause of the disease and the safety of the polio vaccine. The Majigi polio campaign was initiated in 2008 as a pilot trial in Gezawa, a local council with very low uptake of polio vaccination. The average monthly increase in the number of vaccinated children over the subsequent six months after the pilot trial was 1,047 [95% confidence interval (CI): 647–2045, P = 0.001]. An increasing trend in uptake of polio vaccination was also evident (P = 0.001). The outcome was consistent with a decrease or no trend in the detection of children with zero doses. The average monthly decrease in the number of children with zero doses was 6.2 (95% CI: −21 to 24, P = 0.353). Overall, there was a relative increase of approximately 310% in the polio vaccination uptake and a net reduction of 29% of never vaccinated children. The findings of this pilot test show that polio vaccination uptake can be enhanced by programs like Majigi that promote effective communication with the community.

Keywords: Majigi, Polio, Vaccination, Trend, Nigeria

Introduction

Nigeria is yet to achieve complete interruption of wild polio virus (WPV) transmission, since the inception of the global polio eradication effort more than two decades ago.1,2 It is also the only country with a polio epidemic driven by a combination of types 1 and 3 WPV, as well as the vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) type 2.3 Northern Nigeria is one of the world’s largest reservoirs of WPV and accounts for over 80% of the global cases of WPV type 1 reported in 2008.4,5 This outbreak occurred at the same time that the region struggled with an earlier VDPV type 2 outbreak, the largest and longest vaccine-induced epidemic in the history of the polio eradication campaign.6,7 Unfortunately, the VDPV is similar to WPV types 1 and 3 in its ability to attack and cause paralytic diseases.8 The outbreak from this region is linked with the re-emergence of the disease in several polio free countries across Africa, the Middle East and Asia, thereby reversing the global gains achieved previously.4,9

The consistent failure of Nigeria to completely interrupt WPV transmission is largely attributed to children (especially in the north) not sufficiently vaccinated through routine and repeated supplemental vaccination activities.3 Over the years, the program’s campaign strategies failed to connect well with the target population in communities worst hit by the disease, in addition to the operational challenges associated with its implementation.4,5 In some areas in the north, the routine Expanded Program in Immunization is simply non-existent.3 Where it exists, community acceptance is hampered by mistrust, suspicion, and rejection of the program, due to inadequate social mobilization, improper channels of communication, and lack of program commitment and ownership at the local government level.3,10

Carefully planned communication strategies and social mobilization at the community level have contributed greatly in breaking barriers to polio vaccination in the hardest-to-reach and resistant populations. The use of mass media, religious institutions, national advocacy, and sustained community mobilization enhanced the uptake of polio vaccination in hardest-to-reach communities in India and Pakistan leading to reduction in the incidence of polio disease in these countries.11–13 Inclusion of communication through enhanced advocacy, interpersonal engagement and social mobilization is reported to increase absolute and relative (to the baseline) uptakes in polio vaccination in the range of 11–20% and 33–100% respectively.14,15 Mass vaccination campaigns and a mixture of communication strategies remain the most effective approaches for maximum vaccination uptake within the shortest period of time.15,16 However, for high-risk communities with strong community resistance to polio vaccination, innovative strategies that address specific communication concerns are necessary for maximum uptake of vaccination against the disease.17

Lack of strong communication strategies that connect at the grassroots level produced a major setback in Nigeria’s program for polio eradication in 2003 following rumors of the inclusion into the vaccine of an anti-fertility agent or HIV virus as an indirect method of checking population growth in the predominantly Muslim states of the north.18–20 Unfortunately, the rumor rapidly gained acceptance, due to the credence lent to it by religious and political leaders. The controversy led to the suspension of the program in some key northern states including Kano, where it lasted longer, until an investigation ordered by the state government found the vaccine to be safe and further reassured the people by changing the source of the vaccine supply to a trusted producer in the majority Muslim country of Indonesia.18–21

The government of Nigeria is constantly striving to reduce polio transmission, a considerable challenge given the high transmissibility of the disease, and the recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that indicate persistence of WPV and VDPV transmission in some states in the January to June 2011 surveillance period.22,23 The resolve by the government to improve polio vaccination coverage by mobilizing state and local government authorities is rapidly changing the course of the epidemic. Their efforts have resulted in an increased commitment by opinion leaders and civil society organizations to promote program acceptance and create demand for polio vaccination (Abuja declaration, 2009) A major game changer in this renewed effort was the decision to actively engage traditional, religious and political leaders at all levels in sensitization and mobilization activities.

In this article, we discuss the conduct of a grass roots mobilization campaign ‘Majigi’ and the trends in the uptake of polio vaccination among children under the age of 5 years. The campaign systematically engaged the traditional, religious, and political leadership to promote acceptance of the polio vaccination program in high-risk communities where WRV continues to circulate and where resistance to vaccination was strong.

Methods

We analyzed data on the uptake of polio vaccination across Nigeria to identify the state with the lowest uptake and highest number of cases of the disease. Within this highest-risk state, we identified the local council (county) with the lowest uptake and highest number of cases. We then searched for communities within the local council that had the lowest uptake and highest number of reported cases of polio disease. Gezawa local council in Kano state was identified for its high number of reported cases of polio disease and very low vaccination uptake. Danladi B, Sararin Gezawa, Tsamiyar Kara, and Jogana were four communities (settlements) in Gezawa local council where polio disease was frequently reported. These communities were therefore selected for this pilot campaign using convenient sampling. Danladi B was observably a newer settlement and sparsely populated compared to Sararin Gezawa, Tsamiyar Kara, and Jogana.

Majigi in the native Hausa language denotes a road-side film show conducted in communities by mobile vans. For the pilot campaign, a series of polio video clips were composed. Some of the clips focused on the known misconceptions about polio in the selected settlements including the belief that the disease was caused by an evil spirit or demon. Majigi educational intervention targeted the beliefs about the cause of polio disease and the negative attitude towards polio vaccination as two important and changeable predisposing factors for the very low uptake of polio vaccination in these communities.

Regular polio supplemental vaccination activities were conducted in November 2008 and the uptake in these settlements were documented before the Majigi campaign was introduced. After the Majigi awareness campaign, monthly supplemental regular vaccination activities (SVAs) were monitored for the subsequent 6 months and cumulative uptake in each settlement was documented.

Grass roots mobilization

Selected study communities had several layers of opinion leaders and gate keepers. The Majigi polio campaign sought the support of different community gate keepers with a special focus on political, traditional, and religious leaderships. Other groups included traditional healers, birth attendants, town criers, and traditional surgeons. The different leadership groupings were approached separately; their perceptions and feelings were acknowledged and addressed and polio clips were shown to them first, after which their support to mobilize subjects was solicited. Participation of the community leadership was critical in getting their subjects to attend the campaign venue, particularly Muslim religious leaders (Imams), who were the most distrustful of the polio vaccination program.24,25 Having the Imams in these communities as advocates was a great strength for the campaign.

Grass roots campaign

Having the community leaders in attendance boosted the subjects’ morale and encouraged their active participation by listening to polio vaccination campaign messages and asking important questions. The venue was organized to culturally accommodate the entire community membership, including opinion leaders, advocates, men, women, youth, and children. The entire community watched the show from the beginning to the end.

The films were shown in the evening for a period of 1–2 hours, in the following sequence: an opening prayer, welcome speech by the Village head, a formal introduction by the team leader that was followed by an edutainment drama on the consequences of polio rejection. Then, a power point presentation and a computer simulation model on the polio virus, its structure, and types. The routes of transmission, early signs and symptoms and how complications occur after an initial infection were also part of the simulation. This was followed by an emotional movie of victims of the disease, their experiences and frustrations; the different forms of disabilities and associated difficulties encountered by victims and their primary care givers. Finally, recorded video interviews were shown of relatives of the victims, their experiences with the disease, the cost of care, and their frustrations and closing with advice to parents on the need to have their children vaccinated. At the end of each show, feedback was solicited from some participants, including community leaders, on the difference, if any, the show contributed to their understanding of the disease and their readiness to have their children vaccinated against polio.

Evaluation

After the Majigi campaign, monthly SVAs were monitored at the selected sites for 6 successive months. The number vaccinated at each site was documented. The number of children who never received polio vaccination before that time was similarly documented at each site during the follow up SVAs.

Statistical analysis

Mystat 12 (systat software) was used in the analysis. A two sided Mann–Kendall test of trend was used to evaluate the presence of trend and its direction in the polio vaccination uptake and zero doses data generated. The average changes in vaccination uptake and in zero dose detection were computed together with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Significance level was set at an alpha level of 0.05. Trend patterns were further analyzed with time series plots for the different activities at each site.

Results

The baseline polio vaccination uptake among children under the age of five, and the number with zero doses (never received polio vaccination in the past), from the four settlements combined (Danladi B, Sararin Gezawa, Tsamiyar Kara, and Jogana) were 2755 and 125 respectively. At the end of the 6-month follow-up SVA after Majigi, the number vaccinated and zero doses detected were 11 364 and 88 respectively; producing a relative increase of approximately 310% in the polio vaccination uptake and a net reduction of 29% of never vaccinated children.

There is a paucity of data on population denominators of the individual settlements. However, an estimate could be derived from the latest Nigerian Census of 2006, where the population of the Gezawa local council, where the four settlements are located, was 282 062. Since the four settlements studied constitute approximately 30% of the Gezawa population, then we arrive at a figure of 84 620 individuals. Given that children under the age of 5 years accounted for 14% of Nigeria’s population (2006 Census), then we estimate that the number of children under-five in the four settlements is 11 847. Compared to the baseline uptake (before the introduction of Majigi) where only 2755 (23%) of children were covered, uptake increased to 11 364 (96%) in the 6 months subsequent to the Majigi intervention. This represents an absolute increase in polio vaccination uptake of 73% and a relative increase of approximately 310%.

Trends in the uptake of polio vaccination

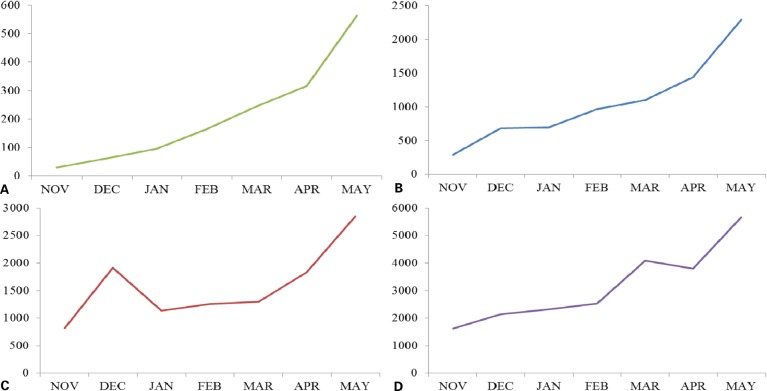

The patterns of the trends in the uptake of polio vaccination in the four individual settlements were provided in the time series plots in Fig. 1. The slope estimates for the mean changes in the uptakes over time and the P values for the Mann–Kendall tests of trends were provided in Table 1. The average monthly increase in the number of children vaccinated at the selected settlements combined was 1047 (95% CI: 647–2045). An increasing trend in uptake of polio vaccination was also evident (P for trend = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Trend pattern in the uptake of polio vaccination over a period of 6 months in the four selected settlements: (A) Danladi B; (B) Sararin Gezawa; (C) Tsamiyar Kara, and (D) Jogana. Uptake (y-axis): number of children vaccinated for polio; monthly SVAs (x-axis): monthly supplemental polio vaccination activities.

Table 1. Average monthly change in the uptake of polio vaccination by settlements.

| Settlements | Mean change in uptake (N) | 95% CI | P value | Trend |

| Danladi B | 70 | 47–117 | <0.0001 | Increasing |

| Sararin Gezawa | 235 | 142–401 | <0.0001 | Increasing |

| Tsamiyar kara | 187 | 24–545 | 0.031 | Increasing |

| Jogana | 617 | 207–887 | 0.001 | Increasing |

| All Settlements | 1047 | 647–2045 | 0.001 | Increasing |

Note: P value: Mann–Kendall test for trend; CI: confidence interval.

N: average increase or decrease in the number of vaccinated children over 6 months period.

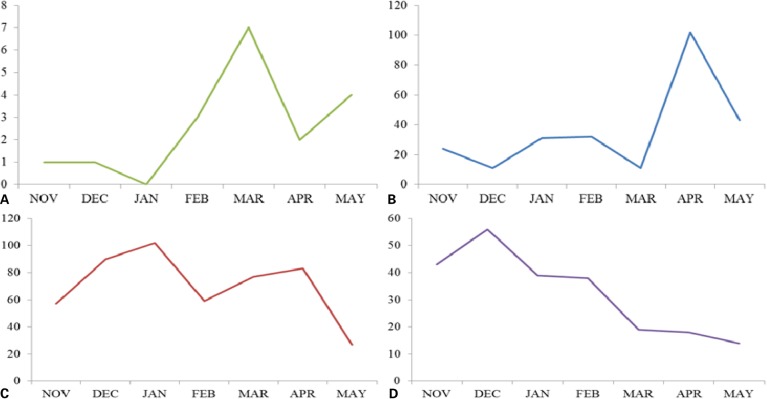

Trends in the detection of children with zero doses

Generally, a pattern of decreasing or no trend was observed in the detection of number of children without a single polio vaccination since birth. Details of the patterns for each of the four settlements are provided in Fig. 2. The slope estimates for the changes in the zero doses detection and the Mann–Kendall P values for test of trends are given in Table 2. The outcome was consistent with a decrease (Jogana settlement) or no trend in the detection of children with zero doses. The average monthly decrease in the number of never vaccinated children (zero doses) was 6.2 (95% CI: −21 to 24; P = 0.353).

Figure 2.

Patterns of zero doses detection among children vaccinated for polio in the four selected settlements: (A) Danladi B; (B) Sararin Gezawa; (C) Tsamiyar Kara, and (D) Jogana. Zero doses detected (y-axis): number of children vaccinated for polio; monthly SVAs (x-axis): monthly supplemental polio vaccination activities.

Table 2. Average monthly change in polio vaccination zero doses detection by settlements.

| Settlement | Mean change in zero dose (N) | 95% CI | P value | Trend |

| Danladi B | 0.6 | −0.5 to 2.0 | 0.088 | No trend |

| Sararin Gezawa | 3.5 | −9.7 to 23 | 0.088 | No trend |

| Tsamiyar kara | −4.3 | −18.9 to 12 | 0.353 | No trend |

| Jogana | −6.3 | −10.1 to 1.7 | 0.001 | Decreasing |

| All Sites | −6.2 | −21.0 to 24 | 0.353 | No trend |

Note: P value: Mann–Kendall test for trend. CI: confidence interval.

N: average increase or decrease in the number of never vaccinated over 6 months period.

Discussion

There is an upward trend in the uptake of polio vaccination in all the settlements after the introduction of Majigi campaign. The consistent increase in the numbers of vaccinated children and the cumulative coverage four times greater than the cumulative value observed with only regular supplemental vaccination activities before the introduction of Majigi suggests a change in the attitude of the targeted communities towards polio vaccination; and decreased community rejection of routine polio vaccination activities. Children who may have received the vaccination in the past but stopped due to the controversies in vaccine safety, accepted the vaccine after Majigi. These returnees may have accounted for the large increase in the number of vaccinated children.

The lack of consistent decrease in the number of never vaccinated children may be explained by the changing population dynamics. Every month, new children and those returning from migration are adding to the baseline numbers of those never vaccinated. Previous defaulters with a positive change in attitude are also adding to this pool. Because of this dynamic, the pool continues to get replenished. However, eventually, we anticipate that a state of equilibrium will be attained and result in an absence of trend in most of the settlements.

Similarly, the lack of significance of the Mann–Kendall test of trend despite an observed cumulative net reduction in the number of never vaccinated children at the end of the evaluation period is because the test is structured to compare data value with a preceding value. The Mann–Kendall statistic increases by one if the latter value is higher and the opposite if it is lower. A consistent increase or decrease in either direction produces strong evidence for an upward or downward trend.

The ability to secure the support and involvement of different cadres of community leaders and to mobilize entire communities has made Majigi a strong campaign tool for polio eradication in similar communities in Northern Nigeria. In addition to the mobilization efforts, the methods used in educating communities and the quality of the messages communicated, also contributed to the observed increase in uptake. Previous studies have underscored the power of effective communication in polio outreach campaigns.26 The absence of several data points prior to the introduction of Majigi made it impossible to compare slopes before and after Majigi. However, it should be noted that these communities were known for their firm resistance to polio vaccination and it is highly unlikely that the increase in the number of children vaccinated for polio in all the settlements would have occurred by chance.

Given the community resistance and the diplomatic friction generated in the past with the polio vaccination campaign in Nigeria, the need for innovative strategies that engage and empower communities, clear misconceptions and provide a sense of ownership have never been greater.27 We believe that Majigi has successfully contributed to filling this gap, and its adoption as a national health tool for polio eradication campaign in Nigeria is an important strategic decision with potential for achieving complete interruption in the transmission of WRV.

Acknowledgments

The first author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Peter Eriki and Suleiman Abdullahi, Abubakar S. Abdul, Dayyabu Muhammad, and Abdurrahman Bichi for facilitating the conduct of the Majigi pilot project (Gezawa initiative). The support of Dr John Vertifeuille, Dr Nancy Knight, Dr Sue Gerber, and Dr Victoria Gammino in providing the formal release of the first author to undertake the assignment is highly appreciated. We thank the entire vaccination team in Kano state and Gezawa LGA including the Ward focal persons for the data collected. The contributions of the staff of the Kano state Ministry of information in the conduct of Majigi is greatly appreciated. We also wish to thank Muhammad Idris (Sayyadi) for his leadership role in the Majigi team.

References

- 1.Progress toward interrupting wild poliovirus circulation in countries with reestablished transmission–Africa, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar. 18;60(10):306–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers ST, Dickson N. Global polio eradication: progress, but determination and vigilance still needed. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1337):100–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammed AJ, Datta KK, Jamjoon G, Magoba-Nyanzi J, Hall R, Mohammed I. 2009. Independent evaluation team’s report on barriers to polio eradication in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Outbreak news. Poliomyelitis in Nigeria and West/Central Africa. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2008;83(26):233–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samba E, Nkrumah F, Leke R. Getting polio eradication back on track in Nigeria. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(7):645–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts L. Infectious disease. Vaccine-related polio outbreak in Nigeria raises concerns. Science. 2007;317(5846):1842. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5846.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts L. Public health. Type 2 poliovirus back from the dead in Nigeria. Science. 2009;325(5941):660–1. doi: 10.1126/science.325_660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins HE, Aylward RB, Gasasira A, Donnelly CA, Mwanza M, Corander J, et al. Implications of a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus in Nigeria. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2360–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai S, Pelletier L, Garner M, Spika J. Increase in poliomyelitis cases in Nigeria. CMAJ. 2008;179(9):930. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renne E. Perspectives on polio and immunization in northern Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(7):1857–69. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obregon R, Chitnis K, Morry C, Feek W, Bates J, Galway M, et al. Achieving polio eradication: a review of health communication evidence and lessons learned in India and Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):624–30. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balraj V, John TJ. Evaluation of a poliomyelitis immunization campaign in Madras city. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64(6):861–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galaway M. Polio communication. J Indian Med Assoc. 2005;103(12):679, 707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waisbord S, Shimp L, Ogden EW, Morry C. Communication for polio eradication: improving the quality of communication programming through real-time monitoring and evaluation. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 1):9–24. doi: 10.1080/10810731003695375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kowli SS, Bhalerao VR, Jagtap AS, Shrivastav R. Community participation improves vaccination coverage. Forum Mond Sante. 1990;11(2):181–4. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obregon R, Waisbord S. The complexity of social mobilization in health communication: top-down and bottom-up experiences in polio eradication. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 1):25–47. doi: 10.1080/10810731003695367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutter RW, Maher C. Mass vaccination campaigns for polio eradication: an essential strategy for success. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;304:195–220. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36583-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jegede AS. What led to the Nigerian boycott of the polio vaccination campaign? PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson HJ, Ghinai I. Lessons from polio eradication. Nature. 2011;473(7348):446–7. doi: 10.1038/473446a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapp C. Nigerian states again boycott polio-vaccination drive. Muslim officials have rejected assurances that the polio vaccine is safe — leaving Africa on the brink of reinfection. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):709. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)15665-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olufowote JO. Local resistance to the global eradication of polio: Newspaper coverage of the 2003–2004 vaccination stoppage in northern Nigeria. Health Commun. 2011;26(8):743–53. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.566830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication — Nigeria, January 2010–June 2011. MMWR Morb Mort Weekly Rep. 2011;60(31):1053–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhutta ZA. The last mile in global poliomyelitis eradication. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):549–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60744-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakabi W. Opponents stymie fight against polio in Nigeria. CMAJ. 2008;179(9):891. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clements CJ, Greenough P, Shull D. How vaccine safety can become political — the example of polio in Nigeria. Curr Drug Saf. 2006;1(1):117–9. doi: 10.2174/157488606775252575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu H.The lost decade of global polio eradication and moving forward. Uirusu.2010;60149–58.Japanese [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufmann JR, Feldbaum H. Diplomacy and the polio immunization boycott in Northern Nigeria. Health Affairs. 2009;28(4):1091–101. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]