Abstract

Novice teen drivers have long been known to have an increased risk of crashing, as well as increased tendencies toward unsafe and risky driving behaviors. Teens are unique as drivers for several reasons, many of which have implications specifically in the area of distracted driving. This paper reviews several of these features, including the widespread prevalence of mobile device use by teens, their lack of driving experience, the influence of peer passengers as a source of distraction, the role of parents in influencing teens’ attitudes and behaviors relevant to distracted driving and the impact of laws designed to prevent mobile device use by teen drivers. Recommendations for future research include understanding how engagement in a variety of secondary tasks by teen drivers affects their driving performance or crash risk; understanding the respective roles of parents, peers and technology in influencing teen driver behavior; and evaluating the impact of public policy on mitigating teen crash risk related to driver distraction.

INTRODUCTION

Per unit of travel, teenage drivers have an elevated fatal and non-fatal crash risk relative to adults [Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 2014]. Concerns about driver distractions have focused in particular on teenagers because they are inexperienced drivers and more likely than adults to engage in risky driving behaviors [Simons-Morton, Ouimet, Zhang, et al., 2011a; Williams, 2003]. Driver distractions occur both when a driver is looking away from the forward roadway (e.g., inside or outside the vehicle), or looking at the forward roadway but not attending (e.g., involved in a cell phone conversation) [Strayer, Drews, Johnston, 2003].

Recent declines in the number of teen crash deaths suggest that progress is being made, largely due to proliferation and improvement in Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) laws in all 50 US states. As a consequence of such programs, novice drivers must generally spend more time in the car learning to drive with their parents, something that has been shown to have a positive effect on attention maintenance [Thomas, Blomberg, Korbelak et al., 2012]. After obtaining their independent license they must generally restrict their driving at night and with passengers. There have been several recent summaries of available knowledge in teen driver safety that identify what we know of the risk factors for teen driver crashes and the most promising strategies for making further reductions in crash risk among teens [e.g., Simons-Morton, Ouimet, 2006; Williams, 2006; Shope, 2007]. However, these summaries have not typically focused on the issue of driver distraction among novice teen drivers.

Teens are unique as drivers for several reasons, many of which have implications specifically in the area of distracted driving:

The widespread prevalence of mobile device use among adolescents and young adults means that these devices likely are present in the cars of most teens.

Their novice driver status may make them more susceptible to the distracting effects of mobile devices, in-vehicle technology, as well as other potential distractions both in and outside the vehicle.

Having peer passengers in the car is a well-known risk factor for serious crashes and there is evidence that peers may serve both as a source of distraction, as well as an adverse influencer of teen decision-making relevant to driving.

Teens are members of families; parents and other family members can exert both positive and negative influence on teen attitudes and behaviors relevant to driving safety.

Teen drivers have been the subject of targeted laws limiting cell phone use and texting, often part of GDL programs, that may provide a public policy foundation on which other intervention programs may be developed.

In the following sections, we address each of these unique circumstances for teen drivers and summarize the available evidence as it relates to distracted driving. We conclude with a summary of recommendations for priority areas for future research on teens and distracted driving.

PREVALENCE AND RISKS OF MOBILE DEVICE USE

Mobile communication and connectivity are commonplace among all U.S. drivers, including teenagers. In a 2012 nationally representative telephone survey of 12–17 year-old children, over three-quarters of teens had cell phones [Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, et al., 2013]. In a 2011 national telephone survey of a representative sample of 6,002 drivers, 93 percent of 18–20 year-old drivers said they own cell phones [Tison, Chaudhary, Cosgrove, 2011].

There is some information about the prevalence of teen drivers’ phone use from self-report surveys or observational surveys of teen populations. Consistently, national self-report surveys indicate that many teens use phones while driving, but the prevalence estimates vary. In a 2009 nationally representative telephone survey of 800 teens 12–17 years old and their parents, 26% of 16–17 year-olds said that they had texted while driving and 52% had talked on a cell phone while driving [Madden, Lenhart, 2009]. In the 2011 national survey on distracted driving, approximately 23% of drivers ages 18–20 years said they had read texts or emails while driving, 17% had sent texts or emails, and 43% had made/accepted phone calls [Tison, Chaudhary, Cosgrove, 2011]. In a 2013 nationally representative survey of 3,103 people 16 and older, 58% percent of 16- to 18-year-old licensed drivers reported talking on a cell phone while driving at least once in the past 30 days, 39% said they had read texts or emails while driving at least once in the past 30 days, and 31% said they had sent texts or emails while driving at least once in the past 30 days [Hamilton, Arnold, Tefft, 2013]. In the 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of over 15,000 US high school students, approximately 45% of students 16 years and older said they had texted while driving in the past 30 days, and 11% texted while driving in the past 2 days [Olsen, Shults, Eaton, 2013].

Two studies directly observed cell phone use among high school student drivers as they exited school parking lots at the end of the day. Observations were conducted during 2011–12 at high schools in California as part of an evaluation of a high-school based educational program on teen driver and passenger safety, with and without special traffic enforcement [McCartt, Wells, 2013]. California prohibits all drivers from talking on hand-held phones and texting, and prohibits all phone use among drivers younger than 18 years. The percentage of drivers engaged in any potentially distracting behavior ranged from 23% to 34% in the preprogram surveys, whereas the rate of all forms of cell phone use was 3–4%. To evaluate North Carolina’s ban on any phone use by drivers younger than 18 years, before and after observations were conducted at high schools in North Carolina and in South Carolina, which has no law limiting teen drivers’ phone use [Goodwin, O’Brien, Foss, 2012]. The rate of phone use among North Carolina teenagers was 11% before the law took effect in December 2006 and 10% two years after, whereas the rate among South Carolina teenagers declined from approximately 15% at baseline to 12%. It should be noted that it is unclear how representative the prevalence of phone use among teenagers exiting high school parking lots may be to other driving situations.

Naturalistic studies can yield more accurate estimates of phone use, although to date, they have been based on small regional samples of drivers. Three naturalistic studies of teen drivers have provided data on the prevalence of distracting behaviors. All were conducted in states with laws limiting teen drivers’ cell phone use so the results may not generalize to states without such laws. In a study of North Carolina novice teen drivers, conducted during 2007–10, 52 teen drivers were observed using an electronic device in 7% of the sampled video clips [Goodwin, Foss, O’Brien, 2012]. The frequency of electronic device use varied considerably by driver, and females were twice as likely as males to use electronic devices. Clips were recorded only during high g-force events like sudden braking or hard cornering, although the thresholds were more sensitive than those used in some other naturalistic studies of teen drivers [Lee, Simons-Morton, Klauer, et al., 2011]. Nevertheless, the estimates of electronic device use may not reflect electronic device use during all driving conditions.

Another study estimated the prevalence of electronic device use among 16–17 year-old novice drivers (20 females, 20 males) who participated in a field operational test of collision warning systems during 2011–2012 in Michigan [Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, unpublished data]. During the study period, Michigan prohibited texting by all drivers. Based on video clips of driving at speeds above 25 mph randomly selected from the 3-week baseline period, the teens engaged in at least one secondary task during 47% of the clips. Cell phones were used in 4% of the clips; approximately half involved texting or manipulating phones.

Klauer, et al. (2013) examined the prevalence and risk of drivers’ phone use with data from 22 female and 20 male newly licensed teens (mean 16.4 years of age) and 43 female and 66 male experienced drivers (mean 36.2 years of age) who were continuously monitored and videotaped from June 2006–September 2008 and January 2003–July 2004, respectively. Klauer, et al. reported the following estimated prevalence of cell phone tasks among the teens in a supplementary appendix: 5% talking/listening on the phone, less than 1% dialing; 1% texting/emailing; and less than 1% reaching for the phone. Prevalence estimates were calculated as the proportion of randomly sampled control periods that involved the secondary phone tasks.

Studies using complementary methodologies have compared teens’ rates of phone use while driving with adults’ rates, and results are mixed. The 2011 national survey of distracted driving found that drivers 18–20 years old and 21–24 years old were more likely than drivers 25 years and older to report sending or receiving texts or emails [Tison, Chaudhary, Cosgrove, 2011], but were less likely than drivers ages 25–54 to report receiving/making phone calls. In the 2013 national survey, 57.8% of drivers 16–18 years old said they had talked on a cell phone while driving at least once in the past 30 days compared with 72.2% of 19–24 year olds, 82.0% of 25–39 year olds, and 71.9% of 40–59 year olds who said the same. In addition, 39% of 16–18 year-old drivers said they had read a text or e-mail or sent a text message while driving at least once in the past 30 days, compared with 42.4% of 19–24 year olds, 55.5% of 25–39 year olds, and 23.7% of 40–59 year-old drivers [Hamilton, Arnold, Tefft, 2013].

Two naturalistic studies compared the prevalence of phone tasks among teen and adult drivers. Using data from the field operational test of collision warning systems described above, the baseline prevalence of distracted driving behaviors among the teen drivers was compared with the prevalence of these behaviors observed during the 12-day baseline in a similar field operational test with 108 adult drivers (54 females, 54 males; ages 21–30, 42–50, and 61–69 years) conducted in 2009–10 [Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, unpublished data]. Teens engaged more often than adults in any kind of secondary task behaviors (47% vs. 41% of clips) but were less likely to use or interact with a cell phone (4% vs. 10% of clips). Adults ages 21–30 years were much more likely than teens to engage in cell phone tasks (17% vs. 4% of clips), especially phone conversations (11% vs. 2% of clips), but teenagers texted more often (1.3% vs. 0.3% of clips).

Based on the proportion of control video clips involving cell phone tasks, Klauer et al. (2013) found that adult drivers talked/listened on cell phones slightly more often than teen drivers (6% vs. 5%). Both teens and adults dialed their phones or reached for their phones in less than 1% of the clips. Overall rates of secondary task engagement, which included phone tasks as well as other potentially distracting activities such as eating and manipulating the radio, were similar for teen drivers (10%) and adult drivers (11% of video clips viewed). The incidence of secondary task engagement did not change over time for adults but increased for teens.

The pervasiveness of cell phone use among teenagers has led to concerns about the consequences for teenage driver safety. The deleterious effects of cell phone use on simulated or instrumented driving performance is well-established [Caird, Willness, Steel et al., 2008; McCartt, Hellinga, Braitman, 2006], and using cell phones while driving has been linked to increases in crash risk [McEvoy, Stevenson, McCartt, et al., 2005; Redelmeier, Tibshirani, 1997] and near-crash risk [Klauer, Dingus, Neale, et al., 2006]. However, the naturalistic study of newly licensed teenagers in North Carolina found that electronic device use was not strongly related to higher g-force events [Goodwin, Foss, O’Brien, 2012]. Klauer et al (2013) observed an elevated risk for crashes and near-crashes among newly licensed teens when dialing (OR 8.32, 95% CI 2.83–24.42) or texting (OR 3.87, 95% CI 1.62–9.25) on a hand-held phone. Among experienced drivers, only cell phone dialing was associated with significantly increased crash or near-crash risk; texting was not assessed among adults.

One study suggested that texting while driving among teenagers might be a single indicator of an overall pattern of risky behavior. The 2011 Youth Risk Behavior survey of high school students found that reported texting while driving in the past 30 days was associated with irregular seat belt use, driving after drinking, and riding with a driver who had been drinking; this association strengthened with more frequent texting while driving [Olsen, Shults, Eaton, 2013].

TEENS ARE NOVICE DRIVERS

The literature that compares teen and novice drivers with more experienced drivers clearly shows that teen and novice drivers are more likely to engage in distracting activities (i.e., they are less skilled strategically) and, when engaged in such activities, they are more likely to do so in a way which increases their risk of crashing (i.e., they are less skilled tactically). Below, the evidence that such is the case is discussed briefly, as are the reasons for such differences. A key theme throughout is that novice teen drivers appear to be more clueless (e.g., not understanding that a hazard could emerge from behind an obstruction) than careless (e.g., understanding that such is the case and not acting in a way to mitigate the risk) [McKnight, McKnight, 2003].

Distraction is most clearly a problem when drivers are looking away from the forward roadway (inside or outside the vehicle). But distraction can also be an issue when teens are looking at the forward roadway and, say, talking to other passengers or on the cell phone (cognitive distraction), which unless a hands-free phone is used, also represents a manual distraction. The review below addresses, where possible, these different forms of distraction.

Strategic Differences

First, consider the evidence that novice teen drivers are less strategic in their engagement with distracting activities inside the vehicle. One controlled field study asked four groups of drivers (teen and young, middle and older adults) at selected points on the road to rate both how risky 81 distracting in-vehicle tasks were and how willing they were to engage in them [Lerner, Boyd, 2005]. Teen drivers were approximately 50% more willing to engage in distracting activities than older drivers. Interestingly, this may be a function of how risky drivers considered the distracting tasks to be. Older drivers rated the tasks as 50% more risky than the teen drivers.

Lee et al. found that newly licensed teens consistently had fewer glances in the rearview mirror, as well as more time with their eyes off the road during a variety of nondriving tasks than experienced adult drivers [Lee, Olsen, Simons-Morton, 2006]. In a follow-up study, the same researchers found that rearview and left mirror glances improved for teens over six months of driving experience, although the percentage of eyes off the road during a reading task and eyes on the display for cell phone based tasks did not improve [Olsen, Lee, Simons-Morton, 2007]. The authors suggested that while experience improves some safety-relevant scanning behaviors, engagement with a secondary task inhibits the performance of scanning for some novice teens.

Tactical differences

Next, consider the likelihood that when teen and novice drivers engage in distracting activities they do so in such a way that is particularly risky. Consider first glances away from the forward roadway inside the vehicle. Not all such glances are dangerous, especially if they are short and driving related (e.g., glancing at the rear view mirror). However, cumulative glances longer than 2 seconds in a 6 second window for whatever purpose are associated with an increase in near crash/crash risk in naturalistic studies [Klauer, Dingus, Neale, et al., 2006; Simons-Morton et al., in press] and single glances longer than 1.6 seconds are associated with simulated crashes in experimental studies [Horrey, Wickens, 2007]. Novice drivers are particularly at risk here since studies have shown that they are more willing to take especially long glances away from the forward roadway than are experienced drivers. For example, the Naturalistic Teen Driver Study has recently found that eye glances away from the forward roadway involving secondary tasks (including but not limited to use of a cell phone) increased the likelihood of a crash/near crash (CNC). Specifically, a single longest glance longer than 2 sec was associated with a nearly 4-fold increase in CNC risk for all secondary tasks and a 5.5-fold increase in risk for wireless secondary tasks [Simons-Morton et al, in press]. In a field study in England, none of the experienced drivers (mean age 36 yrs; median driving experience= 200,000 km) took glances longer than 3 seconds inside the vehicle, but 29% of the inexperienced drivers (mean age 19 yrs; median driving experience= 2,000 km) did [Wikman, Nieminen, Summala, 1998]. In a more recent study conducted on a driving simulator, experienced drivers glanced for longer than 2 seconds at least once inside the vehicle in 20% of the scenarios in which they were asked to perform a secondary task whereas novice teen drivers glanced for longer than 2 seconds at least once in 56.7% of such scenarios [Chan, Pradhan, Pollatsek, et al., 2010].

Similar problems occur when drivers are glancing to the side of the road, at signs, billboards or other objects, though there are many fewer studies upon which one can draw. Here, the measures of interest are not the distribution of the glance durations of the novice and experienced drivers since those distributions are almost identical [Chan, Pradhan, Pollatsek, et al., 2010]. Rather, the difference comes in measures of hazard anticipation and vehicle control which both have been linked to increases in crash risk [Horswill, McKenna, 2004]. Perhaps this is not surprising given the literature on hazard anticipation when no roadside distraction is present. This literature, based on studies that have been carried out both in the laboratory and the field, suggests that novice drivers anticipate hazards less well (look towards the latent threat less often) than experienced drivers when glancing ahead at the forward roadway. [Crundall, Chapman, Trawley, et al., 2012; Pradhan, Hammel, DeRamus, et al., 2005; Lee, Klauer, Olsen et al, 2008]. Similarly, it has been shown the novice drivers anticipate hazards less well than experienced drivers when glancing towards the side at a billboard [Divekar, Pradhan, Pollatsek, et al., 2012]. For example, novice drivers are less likely to glance towards an area from which a pedestrian may emerge from behind a vehicle when asked to gather information from a billboard than when not asked to do so (glances towards a potential threat were used as an indication of hazard anticipation, though someone can glance towards a potential threat and not necessarily recognize that a threat could materialize). Additionally, when glancing towards the side at a billboard novice drivers control the vehicle less well than experienced drivers, exceeding their lane in 26% of the scenarios with roadside distractions as compared with only 4% for the experienced drivers [Divekar, Pradhan, Pollatsek, et al., 2012].

In one study performed on a driving simulator, novice (less than six months driving) and experienced drivers’ behaviors in a number of different scenarios were measured while they dialed, talked on (hands-free) and while they were not talking on a cell phone [Chisholm, Caird, Lockhart, et al., 2006]. Response times to events such as the sudden braking of a lead vehicle, emergence of a pedestrian, or a parked vehicle that pulled into the subject vehicle’s path were slowed more for novice drivers than experienced drivers at baseline (no secondary task), as well as while dialing or talking on the cell phone.

A number of advances have been made in recent years to improve specific driver skills relevant to distraction [Pollatsek, Vlakveld, Kappe, et al., 2011]. The first area to be targeted was hazard anticipation. Simple PC-based training programs have been found to increase hazard anticipation skills among novice drivers for up to one year in the field [Taylor, Masserang, Pradhan, et al., 2011]. The next area to be addressed was distraction inside the vehicle. PC-based training programs to decrease long glances inside the vehicle among novice drivers have been found effective on the simulator and in the field both over the short [Pradhan, Divekar, Masserang, et al., 2011] and the long-term [Thomas, Blomberg, Korbelak, et al., 2012]. Similar training programs to decrease long glances to the side of the road among novice drivers [Divekar, 2013] and to improve hazard mitigation among such drivers [Hamid Samuel, Borowsky et al., 2014] are also effective, but their effects have not yet been evaluated in the field. Although these efforts appear promising, their link to novice driver crashes has not been established.

THE EFFECT OF PEER PASSENGERS

Teenagers spend a significant amount of time with other teens. Adolescents spend more time than children or adults interacting with peers, report the highest degree of happiness when with their peers, and assign the greatest priority to peer norms for behavior [Brown, Larson, 2009]. Teens are an important source of social influence on one another [Ennett, Bauman, 1994; Jaccard, Blanton, Dodge, 2005]. In general, peers can influence behavior by directly encouraging or discouraging it or by modeling the behavior. They can also influence behavior through their general attitude, expectations, and judgments by suggesting how normative and acceptable a behavior is [Ouimet, Pradhan, Simons-Morton, et al., 2013].

The elevated risk of teen driver crash deaths associated with the presence of peer passengers has been known for well over a decade [Chen, Baker, Braver, et al., 2000]. A more recent examination of this phenomenon confirms that compared with having no passengers, increasing numbers of passengers younger than 21 years was associated with a 16- or 17-year-old driver’s increasing relative risk per mile driven of being killed in a crash [Tefft, Williams, Grabowski, 2012]. Similarly, a recent naturalistic driving study of 42 newly licensed teens found that the rate of crashes and near crashes was nearly twice as high when teens drove with more risk-taking friends- as measured by driver report of their friend’s perceived alcohol and drug use, smoking, and driving-related risky behaviors-than when driving alone [Simons-Morton, Ouimet, Zhang, et al., 2011b].

The effect of peer passengers on nonfatal crash risk for teen drivers is not as well established. Inattention due to distraction is one of the main behaviors preceding crashes among young drivers [Curry, Hafetz, Kallan, et al., 2011; McKnight, McKnight, 2003; Braitman, Kirley, McCartt, et al., 2008]. In a survey of over 2,100 high school students in California, 80% of whom reported driving, 38.4% of teens reported that they had been distracted while driving by one or more of their passengers [Heck, Carlos, 2008]. Females were slightly more likely than males to report being distracted, as were students in moderate to high income schools as compared with those in low income schools. The most common types of distraction were talking/ yelling (44.7%), passengers “fooling around” (22.4%), and music/ dancing (15.5%). Approximately 7.5% of drivers reported their passengers intentionally distracting them. In an online survey of 1,000 teens, 47% of teenagers reported that having others in the vehicle with them had a distracting effect, and 44% thought they were safer drivers without their friends in the vehicle [The Allstate Foundation, 2005]. It is interesting to note that teens consider their friends in the car to be a source of distraction, the mechanism of which is not entirely clear. Using the taxonomy of driver inattention described by Regan and Strayer [Regan, Strayer, 2014], peer passengers may serve as a source of driver diverted attention, either by diverting the driver’s eyes from the roadway or by engaging the driver in conversation to the extent that a cognitive distraction is created.

Population-based crash studies indicate that crash-involved males with passengers were more likely to be distracted by something outside the vehicle (RR 1.70 [1.15–2.51]). Conversely, females with passengers were more often engaged in at least one interior non-driving activity (RR 3.87 [1.36–11.06]) prior to the crash, particularly when driving with opposite-gender passengers [Curry, Mirman, Kallan, et al., 2012]. Observational and experimental studies have shown that the presence of teenage passengers is associated with higher involvement in inattention such as higher “looked-but-failed-to-see” driving errors [White, Caird, 2010], lower identification of and reaction time to hazardous situations [Gugerty, Rakauskas, Brooks, 2004], and more driving errors [Rivardo, Pacella, Klein, 2008; Toxopeus, Ramkhalawansingh, Trick, 2011]. The Naturalistic Teen Driver Study has found lower crash/near crash rates for teens when an adult was present in the vehicle but higher when in the presence of risk-taking friends [Simons-Morton, Ouimet, Zhang, et al., 2011b]. Other experimental studies have found performance deterioration when young drivers were accompanied by a passenger who was talking to them, but not when the passenger was silent [Rivardo, Pacella, Klein, 2008; Toxopeus, Ramkhalawansingh, Trick, 2011]. While many studies demonstrate elevated risk in the presence of teenage passengers, the existence of mixed results suggests that there might be specific conditions under which teenage driving risk is increased or decreased in the presence of passengers (e.g., different combinations of driver and passenger gender or based on the specific actions of the passenger).

Given the uncertainty regarding specific mechanisms by which peer passengers may lead to increased distraction for novice teen drivers, the most effective strategy to mitigate this risk is to control the number of peer passengers. This is the justification for passenger restriction provisions in many GDL laws, which have repeatedly been demonstrated to reduce the risk of young driver crashes [Chen, Baker, Li, 2006; Fell, Jones, Romano, et al., 2011; Masten, Foss, Marshall, 2011; McCartt, Teoh, Fields et al, 2010]. Given the complexity of the role of peer passengers on nonfatal crash risk, strategies designed to positively influence peer and driver behaviors to reduce the influence of peers on risky driving or distraction would complement GDL policy. While several peer-to-peer programs have been developed (e.g., Ride Like a Friend, Drive Like you Care- www.teendriversource.org; Teens in the Driver Seat- www.t-driver.com; Operation Teen Safe Driving- www.teensafedrivingillinois.org) few have been evaluated for their effectiveness in changing teen driver or passenger behaviors.

THE ROLE OF FAMILIES

The parents of young drivers play a significant role in the driving safety of their adolescents. Parenting practices that ensure the health and safety of their children are vital to raising responsible and productive adults. Along these lines, there is evidence that monitoring and guidance reduce the likelihood of teens engaging in risky driving. Adolescents who experience this type of involved parenting also have been shown to have fewer violations, and lower crash rates [Hartos, Eitel, Simons-Morton, 2002; Hartos, Eitel, Haynie, et al., 2000; Hartos, Nissen, Simons-Morton, 2001; McCartt, Shabanova, Leaf, 2003]. But the real influence of parents on their teens’ driving behavior is more profound. Long before children begin learning to drive, parents’ driving attitudes and behaviors make a deep impression, including observing the use of cell phones while driving.

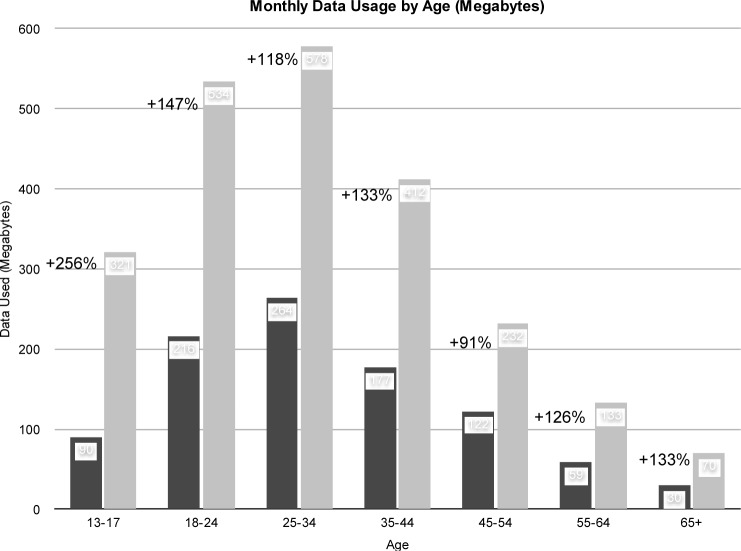

Parents’ driving records [Ferguson, Williams, Chapline, et al., 2001; Senserrick, Boufous, Ivers, et al., 2010], driving style [Bianchi, Summala, 2004; Miller, Taubman-Ben-Ari, 2010], and willingness to engage in risky driving behaviors [Prato, Toledo, Lotan, et al., 2010] all impact teens, who are likely to replicate the behaviors they observe. Moreover, parent attitudes toward technology and distraction create a kind of familial norm. A recent series of Nielson studies reveals the rapid increases in all forms of cell phone use (e.g., texting, data). Even in 2009, young parent-aged adults 25–34 represented 34% of the mobile social network usage, while those aged 35–54 represented another 36%. In 2011, 54% of adults aged 35–44 were using smart phones [The Nielson Company, 2010; The Nielson Company, 2011]. Figure 1 shows the substantial increase in smart phone data usage across adults of parenting age.

Figure 1.

Increase in monthly data usage by age between 2010–2011

The fact that children might be observing such frequent cell phone use in parents and others could influence the broader safety culture. Exacerbating this parent modeling is observing friends who use the cell phone frequently which ultimately leads to a social norm that is difficult to reverse. Such parent and friend modeling have been shown to be an influence in other risky behaviors such as smoking [Hoffman, Sussman, Unger et, al., 2006].

Teens who report having familial relationships that are nurturing and encouraging are also less likely to engage in high-risk behaviors. A survey of over 4,400 10th graders found that positive parental involvement and high levels of support were significantly associated with lower rates of serious violations and crashes [Shope, Waller, Raghunathan, et al., 2001]. A longitudinal study of over 1,000 teens between the ages of 15 and 18 years found that males who reported low family involvement were three times more likely to be involved in an injury crash [Begg, Langley, 1999]. Survey data from more than 4,500 teen drivers revealed that teens whose parents have an authoritative parenting style had approximately half the crash risk, and were less likely to drive after drinking or to use cell phones while driving [Ginsburg, Durbin, Garcia-Espana, et al., 2009].

A study that investigated communication patterns between parents and teens found that frequent discussions about safe driving were positively associated with teens’ attitudes about safe driving. In addition, families with a consensual communication pattern that encouraged expression of opinions and discussion were found to foster more talk about safe driving [Yang, Campo, Ramirez, et al., in press].

US LAWS LIMITING MOBILE DEVICE USE BY TEEN DRIVERS

In response to concerns about the distractions associated with drivers’ cell phone use, almost all U.S. states have implemented laws prohibiting drivers from talking on phones and/or texting [McCartt, Kidd, Teoh, in press]. As of January 2014, only Arizona, Montana, and South Carolina did not prohibit texting by teen drivers. Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia prohibit all uses of cell phones, whether hand-held or hands-free, by novice teen drivers. The bans vary with regard to the ages or licensing stages affected (e.g., drivers younger than 18 years, learner’s permit holders); the uses that are still legal (e.g., reading text messages; talking when the vehicle is stopped); the maximum penalties; and whether the ban is part of the graduated licensing system so that, for example, violations may delay graduation to the next licensing stage. Enforcement may be primary (police officers can stop drivers for violating the cell phone or texting laws) or secondary (officers need another reason to stop drivers before issuing a citation for violating the cell phone or texting law).

Some studies of the effects of laws limiting hand-held cell phone use among drivers of all ages have looked at the effects for teens and young adults combined [e.g., McCartt, Geary, 2004; Trempel, Kyrychenko, Moore, 2011]. There is scant research evaluating cell phone bans targeting teenage drivers. In North Carolina, there was no apparent effect on the observed rate of teen drivers’ phone use associated with a ban on the use of any wireless communication device by drivers younger than 18 years. The rate was not significantly different from the pre-ban rate (11%) when measured 2 years after the ban took effect (10%) [Goodwin, O’Brien, Foss, 2012], relative to use rates at comparison sites in South Carolina, which had no phone ban for teen drivers. The lack of targeted enforcement may have been a factor in these results. When interviewed a few months after the law took effect, a majority of teens and their parents believed that the cell phone ban was enforced rarely or not at all [Foss, Goodwin, McCartt, et al., 2009]. There were no special enforcement campaigns during the two years following implementation of the ban, and the number of citations issued for violations was small [Goodwin, O’Brien, Foss, 2012].

Lim and Chi (2013) attempted to isolate the effects of cell phone bans on the number of drivers younger than 21 years in fatal crashes not involving alcohol during 1996–2010, using state-level annual data. In one set of analyses, there were significantly fewer young driver fatal crash involvements in states with all-driver handheld phone bans, but no effects were found for novice driver bans. In general, the effects of legislation that restricts driver cell phone use on crashes is mixed [McCartt, Kidd, Teoh, in press].

There are no published studies examining the effects of texting bans on teen drivers’ rates of texting or teens’ crash rates. A national survey conducted in 2009 found that 45% of 18–24 year-olds reported texting while driving in states that bar the practice, just shy of the 48% of drivers who reported texting in states without bans [Braitman, McCartt, 2010].

Laws that apply only to teen drivers can be challenging to enforce. In an effort to facilitate enforcement of GDL restrictions, New Jersey implemented a law in May 2010 requiring teens with learner’s permits or probationary licenses to display license plate decals. New Jersey prohibits the use of any kind of wireless communication device by teens with learner’s permits or probationary licenses. Approximately 18% of teens with probationary licenses reported talking on the phone while driving in the past week both before and about a year after the decal requirement was implemented [McCartt, Oesch, Williams, et al., 2013]. The reported rate of texting while driving in the past week declined from 12% to 10%, a non-significant change. Although there were relatively few citations issued for wireless device use compared with other teenage driving restrictions, the number doubled after the decal requirement. This finding was confirmed in a separate analysis of New Jersey state data for the first year following implementation of the decal provision, suggesting that the decal was an initially effective way to enhance police enforcement of a cell phone ban [Curry, Pfeiffer, Localio, et al., 2013].

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Although there is evidence that teenagers frequently use phones while driving, there is little research examining how this behavior affects teenagers’ driving performance or their crash risk. Initial findings from early naturalistic driving studies on the risks associated with specific activities involving cell phones (i.e., reaching for, dialing, talking on, etc.) should be replicated on larger studies, including a description of the circumstances under which engagement in secondary tasks by teen drivers is most common. In addition, how engagement in secondary tasks evolves over the early driving experience of novice teens must be better understood.

Recent technologies, including those that let parents lock their teen’s phone while the teen is in the vehicle [Progue, 2010] or that translate speech to text, have been developed, although the latter have been found to increase cognitive distraction, resulting in, for example, less scanning for hazards while driving [Richtel, Vlasic, 2013]. The effects of such technology on teen drivers’ phone use, driving behavior, or crashes have not been evaluated. Studies of in-vehicle devices that monitor teens’ driving have found challenges in recruiting families and keeping parents engaged, [Carney, McGehee, Lee et al., 2010; Farmer, Kirley, McCartt, 2010] and it is unclear how widely such technologies will be used by families.

The relative importance of visual vs. cognitive distraction for novice teens is not well understood, and is important to the design of driver training programs designed to reduce teen driver distraction. Future novice driver training programs should focus on both strategic and tactical driving skills for novice teens in an effort to raise teens’ awareness of risky driving situations, as well as improve critical driving skills such as scanning and hazard detection. Initial results of driver training programs designed to reduce long glances in and outside of the vehicle show promise, but must be more extensively evaluated in on-road driving scenarios and ultimately in terms of their effects on crashes.

Future research should build on what we know about the influence of peers and parents on teen driving behavior. Specifically, we do not currently understand well the specific mechanisms by which peers may serve as a source of distraction to teen drivers, and under what circumstances this is most likely to occur. Further research is needed to understand how teen drivers might effectively control the influence of their peers, as well as how best to motivate peer passengers to reduce their distracting influence. Parent-oriented and peer-to-peer behavior change programs are promising but have not been rigorously evaluated.

There is evidence that all-driver hand-held cell phone bans can result in large and lasting reductions on use [McCartt, Hellinga, Strouse, et al., 2010], but their effects on crashes is unclear, as is the effect of teen-specific laws. Recent novel legislation designed to enhance police enforcement of teen driving laws shows initial promise [Curry, Pfeiffer, Localio, et al., 2013] but must be evaluated over longer time periods and in multiple jurisdictions.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written as part of the Engaged Driving Initiative (EDI) created by State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company (State Farm®). The EDI Expert Panel was administered by the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine (AAAM) and chaired by Susan Ferguson, Ph.D., President, Ferguson International LLC. The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily the views of State Farm, AAAM or Ferguson International LLC. The authors acknowledge David Kidd from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, for his assistance with identifying studies of interest as well as his critical review of a draft of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Begg DJ, Langley JD. Road Traffic Practices among a Cohort of Young Adults in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1999;112:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A, Summala H. The “Genetics” of Driving Behavior: Parents’ Driving Style Predicts Their Children’s Driving Style. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2004;36:655–659. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitman KA, Kirley BB, McCartt AT, et al. Crashes of Novice Teenage Drivers: Characteristics and Contributing Factors. J Safety Res. 2008;39:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitman KA, McCartt AT. National Reported Patterns of Driver Cell Phone Use in the United States. Traffic Inj Prev. 2010;11:543–548. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2010.504247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Larson J. Peer Relationships in Adolescence Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, Contectal Influences on Adolescent Develpment. Ed. 3. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Caird JK, Willness CR, Steel P, et al. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Cell Phones on Driver Performance. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney C, McGehee DV, Lee JD, et al. Using an Event-Triggered Video Intervention System to Expand the Supervised Learning of Newly Licensed Adolescent Drivers. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1101–1106. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E, Pradhan AK, Pollatsek A, et al. Are Driving Simulators Effective Tools for Evaluating Novice Drivers’ Hazard Anticipation, Speed Management, and Attention Maintenance Skills? Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 2010;13:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Baker SP, Braver ER, et al. Carrying Passengers as a Risk Factor for Crashes Fatal to 16- and 17-Year-Old Drivers. JAMA. 2000;283:1578–1582. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LH, Baker SP, Li GH. Graduated Driver Licensing Programs and Fatal Crashes of 16-Year-Old Drivers: A National Evaluation. Pediatrics. 2006;118:56–62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm S, Caird J, Lockhart J, et al. Novice and Experienced Driving Performance with Cell Phones; Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting; Sage Publications; 2006. pp. 2354–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Crundall D, Chapman P, Trawley S, et al. Some Hazards Are More Attractive Than Others: Drivers of Varying Experience Respond Differently to Different Types of Hazard. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;45:600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Hafetz J, Kallan MJ, et al. Prevalence of Teen Driver Errors Leading to Serious Motor Vehicle Crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43:1285–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Mirman JH, Kallan MJ, et al. Peer Passengers: How Do They Affect Teen Crashes? J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, Localio R, et al. Graduated Driver Licensing Decal Law: Effect on Young Probationary Drivers. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divekar G. Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering. University of Massachusetts; Amherst, MA: 2013. External-to-Vehicle Distractions: Dangerous Because Deceiving. [Google Scholar]

- Divekar G, Pradhan AK, Pollatsek A, et al. External Distractions: Evaluation of Their Effect on Young Novice and Experienced Drivers’ Behavior and Vehicle Control. Transp Res Rec. 2012;2321:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The Contribution of Influence and Selection to Adolescent Peer Group Homogeneity: The Case of Adolescent Cigarette Smoking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer CM, Kirley BB, McCartt AT. Effects of in-Vehicle Monitoring on the Driving Behavior of Teenagers. J Safety Res. 2010;41:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell JC, Jones K, Romano E, et al. An Evaluation of Graduated Driver Licensing Effects on Fatal Crash Involvements of Young Drivers in the United States. Traffic Inj Prev. 2011;12:423–431. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.588296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SA, Williams AF, Chapline JF, et al. Relationship of Parent Driving Records to the Driving Records of Their Children. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2001;33:229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(00)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss RD, Goodwin AH, McCartt AT, et al. Short-Term Effects of a Teenage Driver Cell Phone Restriction. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg KR, Durbin DR, Garcia-Espana JF, et al. Associations between Parenting Styles and Teen Driving, Safety-Related Behaviors and Attitudes. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1040–1051. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin AH, Foss RD, O’Brien NP. Distracted Driving among Newly Licensed Teen Drivers. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety; Washington, DC: 2012. pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin AH, O’Brien NP, Foss RD. Effect of North Carolina’s Restriction on Teenage Driver Cell Phone Use Two Years after Implementation. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;48:363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugerty L, Rakauskas M, Brooks J. Effects of Remote and in-Person Verbal Interactions on Verbalization Rates and Attention to Dynamic Spatial Scenes. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36:1029–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid M, Samuel S, Borowsky A, et al. Evaluation of Effect of Total Awake Time on Driving Performance Skills: Hazard Anticipation and Hazard Mitigation-Simulator Study. Presentation at the 93rd Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting; Washington, D.C.: TRB, National Research Council; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BC, Arnold LS, Tefft BC. Distracted Driving and Perceptions of Hands-Free Technologies: Findings from the 2013 Traffic Safety Culture Index. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hartos J, Eitel P, Simons-Morton B. Parenting Practices and Adolescent Risky Driving: A Three-Month Prospective Study. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:194–206. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartos JL, Eitel P, Haynie DL, et al. Can I Take the Car? Relations among Parenting Practices and Adolescent Problem-Driving Practices. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000;15:352–367. [Google Scholar]

- Hartos JL, Nissen WJ, Simons-Morton BG. Acceptability of the Checkpoints Parent-Teen Driving Agreement - Pilot Test. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2001;21:138–141. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck KE, Carlos RM. Passenger Distractions among Adolescent Drivers. J Safety Res. 2008;39:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BR, Sussman S, Unger JB, et al. Peer Influences on Adolescent Cigarette Smoking: A Theoretical Review of the Literature. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:103–155. doi: 10.1080/10826080500368892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrey WJ, Wickens CD. In-Vehicle Glance Duration: Distributions, Tails, and Model of Crash Risk. Transp Res Rec. 2007;2018:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Horswill MS, McKenna FP. Drivers’ Hazard Perception Ability: Situation Awareness on the Road. Ashgate Publishing; Ashgate, Aldershot, UK: 2004. pp. 155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety . Unpublished Analysis of 2008 data from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Household Travel Survey. General Estimates System, and Fatality Analysis Reporting System. Arlington, VA, unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety Teenagers: Driving carries extra risk for them. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/teenagers/topicoverview. Accessed January 9, 2014.

- Jaccard J, Blanton H, Dodge T. Peer Influences on Risk Behavior: An Analysis of the Effects of a Close Friend. Dev Psychol. 2005;41:135–147. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauer SG, Dingus TA, Neale VL, et al. The Impact of Driver Inattention on near-Crash/Crash Risk: An Analysis Using the 100-Car Naturalistic Driving Study Data. National Highway Safety Administration; Springfield, VA: 2006. pp. 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- Klauer SG, Guo F, Simons-Morton BG, et al. Distracted Driving and Crash Risk Among Novice and Experienced Drivers. NEJM. 2013;370:54–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Olsen ECB, Simons-Morton BG. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No 1980. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies; Washington, D.C.: 2006. Eyeglance Behavior of Novice Teen and Experienced Adult Drivers; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Klauer SG, Olsen ECB, et al. Detection of Road Hazards by Novice Teen and Experienced Adult Drivers. Transportation Research Record. 2008;2078:26–32. doi: 10.3141/2078-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Simons-Morton BG, Klauer SE, et al. Naturalistic Assessment of Novice Teenage Crash Experience. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43:1472–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner N, Boyd S. National Highway Safety Administration: On-Road Study of Willingness to Engage in Distracting Tasks. National Highway Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lim SH, Chi J. Are Cell Phone Laws in the U.S. Effective in Reducing Fatal Crashes Involving Young Drivers? Transport Policy. 2013;27:158–63. [Google Scholar]

- Madden M, Lenhart A. Teens and Distracted Driving: Texting, Talking and Other Uses of the Cell Phone Behind the Wheel. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, et al. Teens and Technology 2013. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2013. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Masten SV, Foss RD, Marshall SW. Graduated Driver Licensing and Fatal Crashes Involving 16- to 19-Year-Old Drivers. JAMA. 2011;306:1098–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Geary L. Longer Term Effects of New York State’s Law on Drivers’ Handheld Cell Phone Use. Inj Prev. 2004;10:11–15. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Hellinga LA, Braitman KA. Cell Phones and Driving: Review of Research. Traffic Inj Prev. 2006;7:89–106. doi: 10.1080/15389580600651103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Hellinga LA, Strouse LM, et al. Long-Term Effects of Handheld Cell Phone Laws on Driver Handheld Cell Phone Use. Traffic Inj Prev. 2010;11:133–141. doi: 10.1080/15389580903515427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Kidd DG, Teoh ET. Laws Targeting Distracted Driving in the United States: Evidence of Effectiveness. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2014;58:101–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Oesch NJ, Williams AF, et al. New Jersey’s License Plate Decal Requirement for Graduated Driver Licenses: Attitudes of Parents and Teenagers, Observed Decal Use, and Citations for Teenage Driving Violations. Traffic Inj Prev. 2013;14:244–258. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.701786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Shabanova VI, Leaf WA. Driving Experience, Crashes and Traffic Citations of Teenage Beginning Drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2003;35:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Wells JK. Effects of the Impact Teen Drivers Program, with and without Special Traffic Enforcement, on Self-Reported and Observed Behaviors of Teenage Drivers. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Teoh ER, Fields M, et al. Graduated Licensing Laws and fatal crashes of teenage drivers; A national study. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2010;11:240–248. doi: 10.1080/15389580903578854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy SP, Stevenson MR, McCartt AT, et al. Role of Mobile Phones in Motor Vehicle Crashes Resulting in Hospital Attendance: A Case-Crossover Study. BMJ. 2005;331:428–430. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38537.397512.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight AJ, McKnight AS. Young Novice Drivers: Careless or Clueless? Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:921–925. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Taubman-Ben-Ari O. Driving Styles among Young Novice Drivers-the Contribution of Parental Driving Styles and Personal Characteristics. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2010;42:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen EOM, Shults RA, Eaton DK. Texting While Driving and Other Risky Motor Vehicle Behaviors among US High School Students. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1708–e1715. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen ECB, Lee SE, Simons-Morton BG. Eye Movement Patterns for Novice Teen Drivers. Does 6 Months of Driving Experience Make a Difference? Transportation Research Record. 2007:8–14. doi: 10.3141/2009-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimet MC, Pradhan AK, Simons-Morton BG, et al. The Effect of Male Teenage Passengers on Male Teenage Drivers: Findings from a Driving Simulator Study. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;58:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollatsek A, Vlakveld W, Kappe B, et al. Driving Simulators as Training and Evaluation Tools: Novice Drivers. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan A, Divekar G, Masserang K, et al. The Effects of Focused Attention Training on the Duration of Novice Drivers’ Glances inside the Vehicle. Ergonomics. 2011;54:917–931. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2011.607245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AK, Hammel KR, DeRamus R, et al. Using Eye Movements to Evaluate Effects of Driver Age on Risk Perception in a Driving Simulator. Hum Factors. 2005;47:840–852. doi: 10.1518/001872005775570961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prato CG, Toledo T, Lotan T, et al. Modeling the Behavior of Novice Young Drivers During the First Year after Licensure. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2010;42:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progue D. Your Phone Is Locked Just Drive. New York Times. 2010 Apr 29;:B1. [Google Scholar]

- Redelmeier DA, Tibshirani RJ. Association between Cellular-Telephone Calls and Motor Vehicle Collisions. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:453–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan MA, Strayer DL. Towards and Understanding of Driver Inattention: Taxonomy and Theory. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2014;58:7–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtel M, Vlasic B. Voice-Activated Technology Is Called Safety Risk for Drivers. New York Times. 2013 Jun 13;:B1. [Google Scholar]

- Rivardo MG, Pacella ML, Klein BA. Simulated Driving Performance Is Worse with a Passenger Than a Simulated Cellular Telephone Converser. N Am J Psychol. 2008;10:265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Senserrick TM, Boufous S, Ivers R, et al. Association between Supervisory Driver Offences and Novice Driver Crashes Post-Licensure. Annals of Advances in Automotive Medicine. 2010;54:309–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shope JT, Waller PF, Raghunathan TE, et al. Adolescent Antecedents of High-Risk Driving Behavior into Young Adulthood: Substance Use and Parental Influences. Accid Anal Prev. 2001;33:649–658. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(00)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shope J. Graduated driver licensing: review of evaluation results since 2002. J Safety Res. 2007;38:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Ouimet MC. Parent involvement in novice teen driving: a review of the literature. Inj Prev. 2006;12:i30–i37. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.011569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Ouimet MC, Zhang Z, et al. Crash and Risky Driving Involvement among Novice Adolescent Drivers and Their Parents. Am J Public Health. 2011a;101:2362–2367. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Ouimet MC, Zhang Z, et al. The Effect of Passengers and Risk-Taking Friends on Risky Driving and Crashes/near Crashes among Novice Teenagers. J Adolesc Health. 2011b;49:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Guo F, Klauer SG, et al. Keep your eyes on the road: Young driver crash risk increases according to the duration of distraction. J Adol Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.021. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer DL, Drews FA, Johnston WA. Cell phone-induced failures of visual attention during simulated driving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2003;9:23–32. doi: 10.1037/1076-898x.9.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor T, Masserang K, Pradhan A, et al. Long-Term Effects of Hazard Anticipation Training on Novice Drivers Measured on the Open Road; Proceedings of the Sixth International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driving Assessment, Training, and Vehicle Design; Lake Tahoe, CA. 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefft BC, Williams AF, Grabowski JG. Teen Driver Risk in Relation to Age and Number of Passengers, United States, 2007–2010. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;14:283–292. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.708887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Allstate Foundation . Chronic: A Report on the State of Teen Driving. The All State Foundation; 2005. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- The Nielson Company Mobile Social Network Usage by Gender and Age. 2010. Available online at http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2010/for-social-networking-women-use-mobile-more-than-men.html (Accessed June 2013).

- The Nielson Company Smart Phone by Age. 2011. Available online at http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2011/generation-app-62-of-mobile-users-25-34-own-smartphones.html (Accessed June 2013).

- Thomas FDI, Blomberg RD, Korbelak KT, et al. Effect of Pc-Based Attention Maintenance Training over Time and as a Function of Driver Experience. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tison J, Chaudhary N, Cosgrove L. National Phone Survey on Distracted Driving Attitudes and Behaviors. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Toxopeus R, Ramkhalawansingh R, Trick L. The Influence of Passenger-Driver Interaction on Young Drivers; Proceedings of the Sixth International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training and Vehicle Design; Lake Tahoe, California. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Trempel RE, Kyrychenko SY, Moore MJ. Does Banning Hand-Held Cell Phone Use While Driving Reduce Collisions? Chance. 2011;24:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- White CB, Caird JK. The Blind Date: The Effects of Change Blindness, Passenger Conversation and Gender on Looked-but-Failed-to-See (LBFTS), Errors. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:1822–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikman A-S, Nieminen T, Summala H. Driving Experience and Time-Sharing During in-Car Tasks on Roads of Different Width. Ergonomics. 1998;41:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AF. Teenage Drivers: Patterns of Risk. J Safety Res. 2003;34:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4375(02)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AF. Young driver risk factors: successful and unsuccessful approaches for dealing with them and an agenda for the future. Inj Prev. 2006;12:i4–i8. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.011783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Campo S, Ramirez M, et al. Family Communication Patterns and Teen Drivers’ Attitudes toward Driving Safety. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2012.01.002. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]