Abstract

Introduction and Objective

This paper provides an overview of the DUQuE (Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe) project, the first study across multiple countries of the European Union (EU) to assess relationships between quality management and patient outcomes at EU level. The paper describes the conceptual framework and methods applied, highlighting the novel features of this study.

Design

DUQuE was designed as a multi-level cross-sectional study with data collection at hospital, pathway, professional and patient level in eight countries.

Setting and Participants

We aimed to collect data for the assessment of hospital-wide constructs from up to 30 randomly selected hospitals in each country, and additional data at pathway and patient level in 12 of these 30.

Main outcome measures

A comprehensive conceptual framework was developed to account for the multiple levels that influence hospital performance and patient outcomes. We assessed hospital-specific constructs (organizational culture and professional involvement), clinical pathway constructs (the organization of care processes for acute myocardial infarction, stroke, hip fracture and deliveries), patient-specific processes and outcomes (clinical effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience) and external constructs that could modify hospital quality (external assessment and perceived external pressure).

Results

Data was gathered from 188 hospitals in 7 participating countries. The overall participation and response rate were between 75% and 100% for the assessed measures.

Conclusions

This is the first study assessing relation between quality management and patient outcomes at EU level. The study involved a large number of respondents and achieved high response rates. This work will serve to develop guidance in how to assess quality management and makes recommendations on the best ways to improve quality in healthcare for hospital stakeholders, payers, researchers, and policy makers throughout the EU.

Keywords: quality management systems, clinical indicators, clinical effectiveness, quality of healthcare, hospitals, cross-national research, patient outcomes

Introduction

Research on quality in health care has built a sizeable knowledge base over the past three decades. Evidence on the effectiveness of organizational quality management and improvement systems has emerged more recently [1–4]. This recent research has addressed several questions. Do quality improvement activities lead to better quality of care? Which quality improvement tools are most effective? How can various quality tools be integrated into a sensitive and effective quality and safety improvement programme? What factors impact on the implementation of quality strategies at hospital level? [5, 6].

Recent European Union (EU) projects, such as the ‘Methods of Assessing Responses to Quality Improvement Strategies’ (MARQUIS) and the ‘European Research Network on Quality Management in Health Care’ (ENQUAL), have attempted to measure the effects of a variety of quality strategies in European hospitals in order to provide information that payers could use as they contract for the care of patients moving across borders. This prior research has had limitations including an incomplete conceptualization of antecedents and effects of quality management systems, methodological weaknesses in measurement strategies and limited use of data on patient outcomes in the evaluation of the effectiveness of these strategies [7–12].

This paper provides an overview of the conceptual framework and methodology of the recently completed DUQuE project (Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe) funded by the European Commission 7th Framework Programme. At its start, the goal of this project was to evaluate the extent to which organizational quality improvement systems, organizational culture, professional involvement and patient involvement in quality management are related to the quality of hospital care, assessed in terms of clinical effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience in a large and diverse sample of European hospitals.

DUQuE had the following specific objectives:

To develop and validate an index to assess the implementation of quality management systems across European hospitals (addressed in three papers by Wagner et al. [13–15]).

To investigate associations between the maturity of quality management systems and measures of organizational culture, professional engagement and patient involvement in quality management, including board involvement on quality and its association with quality management systems (addressed by Botje et al. [16]), the relationship between organizational culture and structure and quality management systems (addressed by Wagner et al. [17]) and the development and validation of the measures for evaluation of clinical management by physicians and nurses (addressed by Plochg et al. [18]).

To investigate associations between the maturity of quality management systems and patient level measures (PLMs) of clinical effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience including the relationships between quality management systems at hospital and pathway levels (addressed by Wagner et al. [19]), patient safety and evidence based management (addressed by Sunol et al. [20]), and patient involvement in quality management (addressed by Groene et al. [21]).

To identify factors influencing the uptake of quality management activities by hospitals, including external pressure as enforced by accreditation, certification or external assessment programmes (addressed by Shaw et al. [22]) and the feasibility of using routine data to compare hospital performance (addressed by Groene et al. [23]).

Conceptual framework

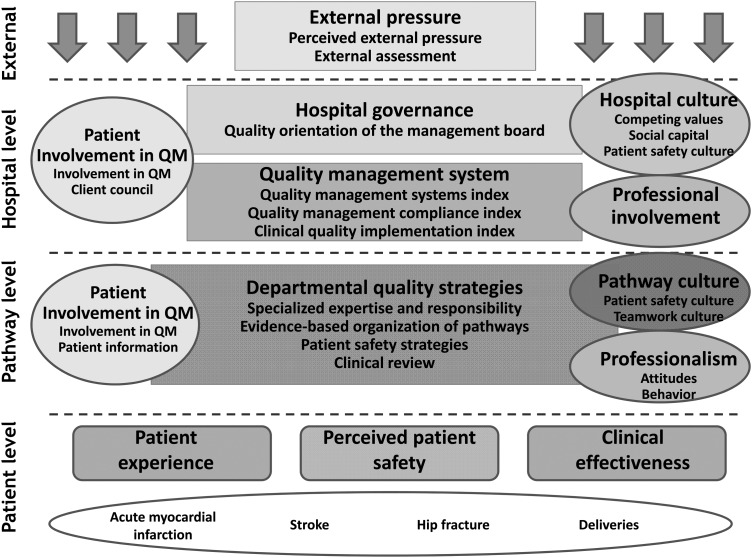

The DUQuE study conceptual model was developed by a range of collaborators with a diverse range of disciplinary backgrounds and expertise. The model addresses four levels: hospital, departmental (or pathway) level, patient's level and external factors influencing uptake of management decisions (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that hospital level quality management systems would be associated with hospital governance and culture, the degree of professional involvement in management (and more concretely in quality management) and the degree of patient involvement in quality management. We further hypothesized that quality management systems in place to manage specific clinical pathways (sometimes referred to as ‘clinical service lines’) would be associated with quality management activities at the hospital and pathway level as well as with pathway culture, professionalism and patients' involvement in quality management. Moreover, we expected quality management systems at both hospital and clinical pathway levels to be associated with patients' experience, and the safety and clinical effectiveness of patient care for four selected conditions (acute myocardial infarction (AMI), obstetrical deliveries, hip fracture and stroke). These conditions were selected because they cover an important range of types of care, there are evidence-based standards for process of care against which compliance could be assessed and there is demonstrated variability in both compliance with process of care measures and outcomes of care (complications, mortality) that would allow for analysis of associations between these measured constructs. Finally, the conceptual model posited that factors external to these quality management systems would also influence the uptake of quality management activities such as perceived pressure from hospital leadership (chief executive officers and governance boards) and external accreditation, certification and standards programmes that offer audit and feedback regarding quality management and performance.

Figure 1.

DUQuE conceptual framework.

Development of measures

For each construct in the conceptual model, published literature was searched to identify measure sets and instruments used previously. Explicit criteria were used to assess and select measures, including psychometric properties, level of evidence and appropriateness in multi-national studies. Whenever a validated measure, instrument or measure set existed and was deemed appropriate, we requested permission to use it in the DUQuE study. Where we found no existing measures or instruments, new measures were developed. After synthesis, 25 measure domains were defined and included in DUQuE (Table 1). Measures were originally designed in English language and translated to local languages when necessary. Table 2 shows the number of cases expected and finally gathered for each instrument designed to operationalize measures according to hospital type. All of the final instruments used are available at the DUQuE's website [24].

Table 1.

Constructs, measure domains and data collection methods used

| Construct name | Measure domain | Measure domain definition | Data collection method | Administration system |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External pressure | Perceived external pressure | Influence in hospital management of external factors (accreditation, contracts, press …) | Questionnaire to CEO | Electronically administered questionnaire |

| External assessment | Whether the hospital has undergone external assessment (accreditation, ISO) | Assessment at hospital level performed by an external visitor | Visit at hospital level performed by an external visitor. Both, paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Hospital governance | Quality orientation of the management board | Including background in quality, time allocated for quality in the meetings, etc. | Questionnaire to CEO | Electronically administered questionnaire |

| Hospital level quality management systems (QMS) | Quality Management System Index (QMSI) | Index to assess the implementation of quality management system at hospital level | Questionnaire to hospital quality manager (QM) | Electronically administered questionnaire |

| Quality management Compliance Index (QMCI) | Measuring compliance with quality management strategies to plan, monitor and improve the quality of care | Assessment at hospital level performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Clinical Quality Implementation Index (CQII) | Index measuring to what extent efforts regarding key clinical quality areas are implemented across the hospital | Assessment at hospital level performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Hospital culture | Organizational culture Competing values framework (CVF) | CVF has two dimensions: structure of internal processes within the hospital and orientation of the hospital to the outside world | Questionnaires to Chair of Board of Trustees, CEO, Medical Director and the highest ranking Nurse | Electronically administered questionnaire |

| Social capital | Measures common values and perceived mutual trust within the management Board | Questionnaire to CEO | Electronically administered questionnaire | |

| Hospital patient safety culture | Safety Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ): Two dimensions measuring perceptions on patient safety culture in terms of teamwork and safety climate | Questionnaires to leading physicians and nurses | Electronically administered questionnaire | |

| Hospital professional involvement | Professional involvement in management | Measures leading doctors and nurses involvement in management, administration and budgeting and managing medical and nursing practice | Questionnaires to leading physicians and nurses | Electronically administered questionnaire |

| Patient involvement in quality management | Patient involvement in quality at hospital level | This construct assesses patients' involvement in setting standards, protocols and quality improvement projects. These constructs used in previous research (Groene, ENQUAL) | Questionnaire to hospital quality manager | Electronically administered questionnaire |

| Client council | Measures existence and functioning of client council | Questionnaire to hospital quality manager | Electronically administered questionnaire | |

| Department quality strategies | Specialized expertise and responsibility (SER) | Measures if specialized expertise and clear responsibilities are in place at pathway level | Assessment at pathway or department settings performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms |

| Evidence-based organization of pathways (EBOP) | Measures if pathways are organized to deliver existing evidence base care | Assessment at pathway or Department settings performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Patient safety strategies (PSS) | Measures if most recommended safety strategies are in place at ward level | Assessment at pathway or department settings performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Clinical review (CR) | Measures if clinical reviews are performed systematically | Assessment at pathway or department settings performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Department pathway culture | Pathway patient safety culture | SAQ: two dimensions measuring perceptions on patient safety culture in terms of teamwork and safety climate | Questionnaires to physicians and nurses at pathway level | Questionnaire electronically administered |

| Professionalism | Professionalism | Measures professional attitudes towards professionalism and behaviour in their clinical area | Questionnaires to professionals at pathway level | Questionnaire electronically administered |

| Patient involvement in quality management | Patient involvement in quality at departmental level | This construct assesses patient's involvement in setting standards, protocols and quality improvement projects. These constructs used in previous research (Groene, ENQUAL) | Questionnaire to manager of care pathways or head of department | Questionnaire electronically administered |

| Patient information strategies in departments | Measures if information literature, surveys and other activities are conducted at pathway or department level | Assessment at pathway or department settings performed by an external visitor | Both paper and electronically administered audit forms | |

| Patient experience | Generic patient experience | Generic measure of patient experience (NORPEQ) | Patient survey | Paper-based questionnaire |

| Perceived patient involvement | Measures perceived involvement of care (from Commonwealth Fund sicker patients survey) | Patient survey | Paper-based questionnaire | |

| Hospital recommendation | Measure of hospital recommendation (from HCAHPS) | Patient survey | Paper-based questionnaire | |

| Perceived continuity of care | Measures patient-perceived discharge preparation (Health Care Transition Measure) | Patient survey | Paper-based questionnaire | |

| Perceived patients safety | Perceived patients safety | Measures patients' perception of possible harm and its management | Patient survey | Paper-based questionnaire |

| Clinical effectiveness | Clinical effectiveness indicators for AMI, stroke, hip fracture and deliveries | A set of clinical process composite indicators based on their high evidence of impacting patients' outcomes | Patient clinical charts Administrative hospital data |

Electronic data collection sheet |

Table 2.

Data collection and response rates in the DUQuE project

| Type of questionnaire | Expected n questionnaires per hospital with partial data collection | Expected n questionnaires per hospital with comprehensive data collection | Total questionnaires expected | Total questionnaires obtained | Average response rate | Response rate country rangea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional questionnaires: | 10 759 | 9857 | 90 | 78–98 | ||

| A. Chair of the Board of Trustees | 1 | 1 | ||||

| B. Chief executive officer | 1 | 1 | ||||

| C. Chief medical officer | 1 | 1 | ||||

| D. Quality manager | 1 | 1 | ||||

| E. Leading physicians and nurses | 20 | 20 | ||||

| F. Manager of care pathways or head of department | 0 | 4 | ||||

| G. Professionals at pathway level | 0 | 80 | ||||

| M. Highest ranking nurse in the hospital | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Patient questionnaires | 0 | 120 | 8670 | 6750 | 75 | 52–90 |

| Chart reviews | 0 | 140 | 10 115 | 9082 | 89 | 66–100 |

| External visits | 0 | 1 | 74 | 74 | 100 | 100–100 |

| Administrative routine data | 1 | 1 | 188 | 177 | 94 | 77–100 |

| Total amount | 26 | 371 | 29 806 | 25 940 | 87% |

aBy country, % response rate range (minimum–maximum).

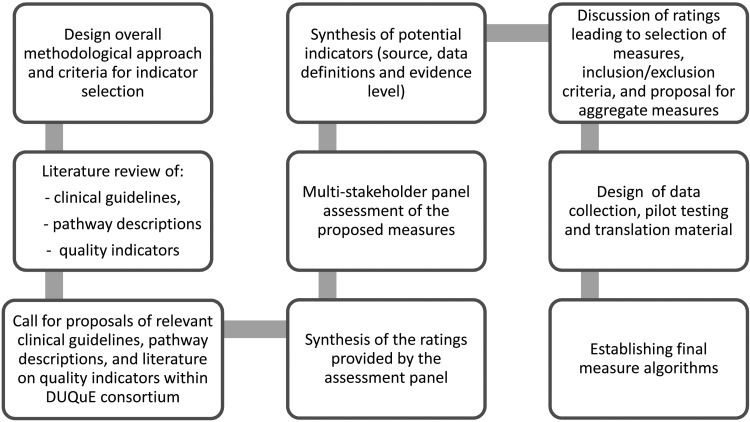

The DUQuE project used a variety of measures to assess patient experience including a generic patient experience instrument (NORPEQ), a measure of patient-perceived discharge preparation (Health Care Transition Measure) and a single-item measure for perceived involvement of care and hospital recommendation in a DUQuE patient survey instrument. In addition, clinical indicators to assess key patient processes and outcomes were selected using a multi-step process (Fig. 2) that included a search of peer-reviewed literature and extensive searches of guidelines and other sources (a substantial amount of patient safety literature appears in the so-called ‘grey literature’ and not in peer-reviewed publications).

Figure 2.

Development process of DUQuE clinical indicators.

Clinical indicators for each of the four clinical conditions included in the study were collected, reviewed and rated based on the level of evidence according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine [25] and their previous use in multi-national studies. In the next step, five relevant European scientific societies, five individual key experts with knowledge of the health-care systems in Europe and the eight DUQuE field test coordinators, named country coordinators, took part in a multi-stakeholder panel. Participants assessed the proposed clinical indicators using a rating matrix. Criteria applied to select four to six clinical indicators of process and outcome per condition were: comparability, data availability, data quality across the eight countries participating, relevance in the different EU health-care settings and ability of the PLM to distinguish between hospitals. The country coordinators offered structural and epidemiological information about treatment of each of the four clinical conditions. The final indicators were selected from among those with the highest level of evidence and the best multi-stakeholder panel rating results with previous use of an indicator in clinical cross-national comparisons given special consideration.

In each condition one or two composite measures were developed that combined the selected indicators for the purpose of a global analysis of the condition. Table 3 shows the final DUQuE indicator list with the source and level of evidence rating for each. Data from clinical indicators were collected via medical records abstraction using a standardized data collection method.

Table 3.

Clinical indicators and composite measures selected for the DUQuE project

| Condition | Main clinical indicators used | Sourcea | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) | Fibrinolytic agent administered within 75 min of hospital arrival | AHRQ | A |

| Primary percutaneous coronary intervention within 90 min | AHRQ | A/B | |

| Thrombolytic therapy or primary percutaneous coronary intervention given | See 1a and 2a | See 1a and 2ª | |

| Therapy given on timeb | |||

| Anti-platelet drug prescribed at discharge (ASPRIN) | AHRQ | A | |

| Beta blocker prescribed at discharge | AHRQ | A | |

| Medication with statin prescribed at discharge | AHRQ | A | |

| ACE inhibitors prescribed at discharge | AHRQ | A | |

| Appropriate medications: all four of anti-platelet, beta blocker, statin, ACE inhibitor) prescribed at dischargeb | |||

| Deliveries | Epidural anaesthesia applied within 1 h after being ordered for vaginal births | The Danish Clinical Registries | D |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | WHO | D | |

| Blood transfusion during intended or realized vaginal birth | The Danish Clinical Registries | B | |

| Acute Caesarean section | |||

| Obstetric trauma (with instrumentation) | OECD | B | |

| Obstetric trauma (without instrumentation) | OECD | B | |

| Mother complication: unplanned C-section, blood transfusion, laceration and instrumentationb | The Danish Clinical Registries | B | |

| Adverse birth outcome (child)b | The Danish Clinical Registries | B | |

| Birth with complicationsb | The Danish Clinical Registries | B | |

| Hip fracture | Prophylactic antibiotic treatment given within 1 h prior to surgical incision | RAND | A |

| Prophylactic thromboembolic treatment received on the same day as admission (within 24 h or on same date when (one or more) times not provided) | RAND | A | |

| Early mobilization (within 24 h or before next day when (one or more) times not provided) | The Danish Clinical Registries | B | |

| In-hospital surgical waiting time <48 h [or 1 day when (one or more] times not provided) | OECD | C | |

| Percentage of recommended care per case: indicators prophylactic antibiotic treatment within 1 h, prophylactic thromboembolic treatment within 24 h, early mobilization within 24 h, in-hospital surgical waiting time <48 h = YES)b | |||

| Stroke | Admitted to a specialized stroke unit within 1 day after admission | The Danish Clinical Registries | A |

| Platelet inhibitor treatment within 2 days after admission | The Danish Clinical Registries | A | |

| Diagnostic examination within first 24 h/same day after admission using CT or MRI scan | The Danish Clinical Registries | D | |

| Mobilized within 48 h (or 2 days when times are missing) after admission? | The Danish Clinical Registries | C/D | |

| Appropriate stroke management. All three applied: Platelet inhibitor treatment within 2 days after admission, Diagnostic examination (CT or MRI) within first 24 h and Mobilized within 48 hb |

aAccording the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine.

bComposite measures (aggregation of indicators).

Design and fieldwork protocol

DUQuE was designed as a multi-level cross-sectional study with data collection in eight countries. Selected countries had to have a sufficient number of hospitals to fulfil sampling criteria, represent varied approaches to financing and organizing health care, have research staff with experience in conducting comprehensive field tests and represent the geographical reach of the EU. Turkey was included because of the status of its EU candidacy at the start of the project. The countries invited to participate in the field test were the Czech Republic, England, France, Germany, Poland, Portugal, Spain and Turkey.

Sampling strategy

We aimed to collect data for the assessment of hospital-wide constructs from up to 30 randomly selected hospitals in each of the 8 participating countries (Nh = 240 hospitals, maximum). In each country, for 12 of these 30 hospitals we carried out comprehensive data collection at pathway and patient levels (nh = 96 hospitals, maximum).

General acute care hospitals (public or private, teaching or non-teaching) with a minimum hospital size of 130 beds were considered for inclusion into the study. In addition, for comprehensive data collection, hospitals were required to have a sufficient volume of care to ensure recruitment of 30 patients per condition over a 4-month period (a sample frame of a minimum of 90 patients). Specialty hospitals, hospital units within larger hospitals, and hospitals not providing care for the four clinical conditions of study were excluded from further consideration.

Each country coordinator provided to the Central Project Coordination Team (CPCT) a de-identified hospital list (including all hospitals with more than 130 beds, ownership and teaching status) of each country for sampling purposes. A simple random sample was taken to identify candidate hospitals for comprehensive and partial data collection; this was oversampled to anticipate withdrawal of participants. The sampling strategy proved efficient as the distribution of key characteristics such as number of beds, ownership and teaching status did not differ between country-level samples and national distributions.

Recruitment

After the preliminary sample of hospitals was selected, each country coordinator formally invited the hospital chief executive officers (CEOs) to participate. A total of 548 hospitals were approached of which 192 agreed to participate. The percentage of hospitals accepting participation ranged from 6.7 to 96.8% between countries. The main reasons of declining to participate were related to time constraints, organizational aspects and the complexity of the study. Data from 188 hospitals in 7 participating countries were included in the final analysis. After significant efforts, hospitals in England were not included partly due to delays in obtaining ethical approval and also extensive difficulty recruiting hospitals.

Data collection

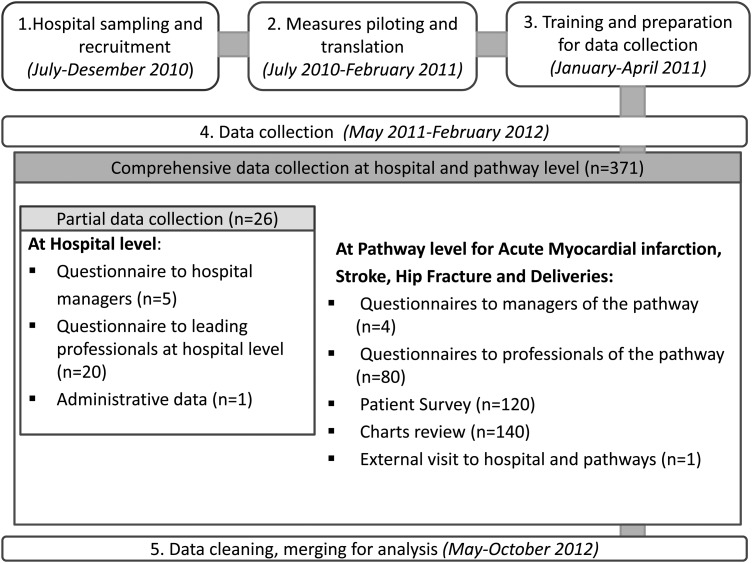

The CPCT facilitated communication and problem solving during the ongoing field test process. Preparation began in July 2010 and included sampling, recruitment, back and forward translation and piloting of measures, preparation of materials and training hospital coordinators in charge of retrieving data. Data collection began formally in May 2011 and was completed by February 2012. Several coordination actions enabled timely data collection of professional questionnaires, patients' surveys, charts review, external visits and administrative data (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Stages of DUQuE field test.

An information technology platform was created to support central collection of responses to professional questionnaires and data from site visits. Among a subset of 88 hospitals a comprehensive data collection required them to provide administrative data and administer 371 questionnaires including patients, professionals, chart reviews and an external visit (Table 2). The remaining hospitals provided administrative data and administered professional questionnaires to 25 respondents. The overall response rate for the different questionnaires was between 75 and 100% for the assessed measures (Table 2).

Once field period was completed, all data collected was cross-checked by the CPCT to ensure that hospital and respondents’ codes matched per country. Data were also checked for any discrepancies, specifically the chart review files. All data sets were merged and transferred to the data analysis team.

Ethical and confidentiality

DUQuE fulfilled the requirements for research projects as described in the 7th framework of EU DG Research [26]. Data collection in each country complied with confidentiality requirements according to national legislation or standards of practice of that country.

Discussion

The DUQuE project has achieved several important advances that are detailed in the papers included in this supplement. First, it is the first large-scale quantitative study exploring across a broad and diverse sample of European hospitals several features of the implementation of hospital quality management systems and their impact on quality and safety. It represents a major advance over previous research by including patient-level processes and outcomes, enabling study of the impact of current quality improvement strategies on patient care and outcomes. Secondly, it made use of a comprehensive conceptual model describing the functioning of hospital quality management systems and supporting a deliberate empirical, quantitative measurement and analytic approach. Thirdly, it succeeded in collecting and linking large amounts of data from hospitals in seven countries including professional surveys (management and baseline), patient surveys, clinical indicators from medical records and administrative data from participating hospitals. Fourthly, the DUQuE coordination structure and protocol including periodic follow-up and feedback to hospital coordinators enabled the project to obtain the active participation of hospitals and high response rates. Finally, the project led to the development of new measures, reported in this supplement, which can be used in future research.

Despite these many achievements, the study has limitations that are worth highlighting. First, the study was not designed or powered to report on the results for each country. We pooled data across countries and addressed heterogeneity in country-level estimates in our statistical modelling using an approach that allowed country-level baselines and effects to vary. Further covariate adjustment included hospital size, ownership and teaching status. A second limitation is that we used a cross-sectional study design. This was considered most appropriate for hypothesis testing in this project because it requires a relatively shorter time commitment and fewer resources to conduct, although ultimately does not allow strong conclusions about causality [27]. The use of directed-acyclic graphs guided the development of our statistical models, incorporating theory and knowledge derived from previous research findings and this approach helps somewhat in strengthening causal inferences from the project results. A third limitation is related to the sampling strategy. Although a random sampling strategy was used, a generalization to participating countries and hospitals is limited because hospitals volunteered to participate in the project introducing potential self-selection bias. However, our analysis shows substantial variations in the implementation of quality criteria, and outcomes, suggesting that the effect of self-selection may be less problematic. A final limitation is the existence of systematic biases due to self-report and to country differences in data coding. The study relied on self-reported data that may introduce social desirability bias. In many instances, we were able to use other data sources to verify responses, but not for all measures. Measuring clinical practice using clinical record review may introduce systemic biases related to medical record completeness practice variations among countries, but some of this is handled through statistical adjustment for the effects of country, hospital size, ownership and teaching status. In conclusion, while the design is prone to a number of limitations we anticipated potential problems and addressed them in study design and our analytical strategy.

This supplement presents the first set of results from the DUQuE project. It includes quality management indexes conceptualization and development, validation of new measures and results of tests of associations between some of the main constructs. Future publications are intended to address remaining questions and secondary analyses of this very large database. For example, papers addressing the associations between quality management systems and key patient processes and outcomes are planned. In addition to the research publications, the DUQuE project website offers a set of recommendations presented in an appraisal scheme derived from the broader perspective of this investigation and summarized for hospital managers buyers and policy makers who may find it useful as they redesign organization-wide approaches to hospital care to achieve the highest levels of quality and safety [24].

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission's Seventh Framework Program FP7/2007–2013 under the grant agreement number [241822]. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 241822.

Acknowledgements

The DUQuE indicators were critically reviewed by independent parties before their implementation. The following individual experts critically assessed the proposed indicators: Dr J. Loeb, The Joint Commission (All four conditions), Dr S. Weinbrenner, Germany Agency for Quality in Medicine (All four conditions), Dr V. Mohr, Medical Scapes GmbH & Co. KG, Germany (all four conditions), Dr V. Kazandjian, Centre for Performance Sciences (all four conditions), Dr A. Bourek, University Center for Healthcare Quality, Czech Republic (Delivery). In addition, in France a team reviewed the indicators on myocardial infarction and stroke. This review combined the Haute Autorité de la Santé (HAS) methodological expertise on health assessment and the HAS neuro cardiovascular platform scientific and clinical practice expertise. We would like to thank the following reviewers from the HAS team: L. Banaei-Bouchareb, Pilot Programme-Clinical Impact department, HAS, N. Danchin, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, Past President, J.M. Davy, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, A. Dellinger, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, A. Desplanques-Leperre, Head of Pilot Programme-Clinical Impact department, HAS, J.L. Ducassé, CFMU, French Emergency Medicine-learned and scientific society, practices assessment, President, M. Erbault, Pilot Programme-Clinical Impact department, HAS, Y. L'Hermitte, Emergency doctor, HAS technical advisor, B. Nemitz, SFMU, French Emergency Medicine scientific society, B. Nemitz, SFMU, French Emergency Medicine scientific society, F. Schiele, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, C. Ziccarelli, CNPC French cardiology learned society, M. Zuber, SFNV, Neurovascular Medicine scientific and learned society, President. We also invited the following five specialist organization to review the indicators: European Midwifes Association, European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, European Stroke Organisation, European Orthopaedic Research Society, European Society of Cardiology. We thank the experts of the project for their valuable advices, country coordinators for enabling the field test and data collection, providing feedback on importance, metrics and feasibility of the proposed indicators, hospital coordinators to facilitate all data and the respondents for their effort and time to fill out the questionnaires.

Appendix

The DUQuE project consortium comprises: Klazinga N, Kringos DS, MJMH Lombarts and Plochg T (Academic Medical Centre-AMC, University of Amsterdam, THE NETHERLANDS); Lopez MA, Secanell M, Sunol R and Vallejo P (Avedis Donabedian University Institute-Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona FAD. Red de investigación en servicios de salud en enfermedades crónicas REDISSEC, SPAIN); Bartels P and Kristensen S (Central Denmark Region & Center for Healthcare Improvements, Aalborg University, DENMARK); Michel P and Saillour-Glenisson F (Comité de la Coordination de l'Evaluation Clinique et de la Qualité en Aquitaine, FRANCE) ; Vlcek F (Czech Accreditation Committee, CZECH REPUBLIC); Car M, Jones S and Klaus E (Dr Foster Intelligence-DFI, UK); Bottaro S and Garel P (European Hospital and Healthcare Federation-HOPE, BELGIUM); Saluvan M (Hacettepe University, TURKEY); Bruneau C and Depaigne-Loth A (Haute Autorité de la Santé-HAS, FRANCE); Shaw C (University of New South Wales, Australia); Hammer A, Ommen O and Pfaff H (Institute of Medical Sociology, Health Services Research and Rehabilitation Science, University of Cologne-IMVR, GERMANY); Groene O (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK); Botje D and Wagner C (The Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research-NIVEL, the NETHERLANDS); Kutaj-Wasikowska H and Kutryba B (Polish Society for Quality Promotion in Health Care-TPJ, POLAND); Escoval A and Lívio A (Portuguese Association for Hospital Development-APDH, PORTUGAL) and Eiras M, Franca M and Leite I (Portuguese Society for Quality in Health Care-SPQS, PORTUGAL); Almeman F, Kus H and Ozturk K (Turkish Society for Quality Improvement in Healthcare-SKID, TURKEY); Mannion R (University of Birmingham, UK); Arah OA, Chow A, DerSarkissian M, Thompson CA and Wang A (University of California, Los Angeles-UCLA, USA); Thompson A (University of Edinburgh, UK).

References

- 1.Cohen AB, Restuccia JD, Shwartz M, et al. A survey of hospital quality improvement activities. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65:571–95. doi: 10.1177/1077558708318285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schouten LM, Hulscher ME, van Everdingen JJ, et al. Evidence for the impact of quality improvement collaboratives: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;336:1491–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39570.749884.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Health sector accreditation research: systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:172–84. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suñol R, Garel P, Jacquerye A. Cross-border care and healthcare quality improvement in Europe: the MARQuIS research project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:i3–7. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suñol R, Vallejo P, Thompson A, et al. Impact of quality strategies on hospital outputs. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:i62–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner C, De Bakker DH, Groenewegen PP. A measuring instrument for evaluation of quality systems. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999;11:119–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/11.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner BJ, Alexander JA, Shortell SM, et al. Quality improvement implementation and hospital performance on quality indicators. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:307–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suñol R, Vallejo P, Groene O, et al. Implementation of patient safety strategies in European hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:i57–61. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groene O, Klazinga N, Walshe K, et al. Learning from MARQUIS: the future direction of quality and safety in healthcare in the European Union. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:i69–74. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombarts MJMH, Rupp I, Vallejo P, et al. Differentiating between hospitals according to the ‘maturity’ of quality improvement systems: a new classification scheme in a sample of European hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:i38–43. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw C, Kutryba B, Crisp H, et al. Do European hospitals have quality and safety governance systems and structures in place? Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:i51–6. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groene O, Botje D, Suñol R, et al. A systematic review of instruments that assess the implementation of hospital quality management systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2013;5:i1–17. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner C, Groene O, Thompson CA, et al. Development and validation of an index to assess hospital quality management systems. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):16–26. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner C, Groene O, DerSarkissian M, et al. The use of on-site visits to assess compliance and implementation of quality management at hospital level. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):27–35. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner C, Thompson CA, Arah OA, et al. A checklist for patient safety rounds at the care pathway level. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):36–46. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botje D, Klazinga NS, Suñol R, et al. Is having quality as an item on the executive board agenda associated with the implementation of quality management systems in European hospitals: a quantitative analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):92–99. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner C, Mannion R, Hammer A, et al. The associations between organizational culture, organizational structure and quality management in European hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):74–80. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plochg T, Arah OA, Botje D, et al. Measuring clinical management by physicians and nurses in European hospitals: development and validation of two scales. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):56–65. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner C, Groene O, Thompson CA, et al. DUQuE quality management measures: associations between quality management at hospital and pathway levels. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunol R, Wagner C, Arah OA, et al. Evidence-based organization and patient safety strategies in European hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):47–55. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groene O, Sunol R, Klazinga NS, et al. Involvement of patients or their representatives in quality management functions in EU hospitals: implementation and impact on patient-centred care strategies. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):81–91. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw CD, Groene O, Botje D, et al. The effect of certification and accreditation on quality management in 4 clinical services in 73 European hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):100–107. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groene O, Kristensen S, Arah OA, et al. Feasibility of using administrative data to compare hospital performance in the EU. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):108–115. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DUQuE project (Deeping our understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe) http://www.duque.eu. (29 May 2013, date last accessed)

- 25.Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D, et al. Martin Dawes since November 1998. Updated by Jeremy Howick March 2009. Centre for Evidence Based Medicine www.cebm.net. (29 May 2013, date last accessed)

- 26.Groene O, Klazinga N, Wagner C, et al. Investigating organizational quality improvement systems, patient empowerment, organizational culture, professional involvement and the quality of care in European hospitals: the ‘Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe (DUQuE)’ project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:281. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]