Abstract

This study examined the specificity of relations between parent / caregiver behaviors and childhood internalizing and externalizing problems in a sample of 70 fourth grade children (64% male, mean age = 9.7 years). Specificity was assessed via (a) unique effects, (b) differential effects, and (c) interactive effects. When measured as unique and differential effects, specificity was not found for warmth or psychological control but was found for caregiver’s use of behavior control. Higher levels of behavior control were uniquely related to lower levels of externalizing problems and higher levels of internalizing problems; differential effects analyses indicated that higher levels of behavior control were related to decreases in the within-child difference in relative levels of level of internalizing vs. externalizing problems. Interactive relations among the three parenting behavior dimensions also were identified. Although caregivers emphasized different parenting behavior dimensions across two separate caregiver-child interaction tasks, relations between parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology did not vary as a function of task. These findings indicate the importance of assessing and simultaneously analyzing multiple parenting behavior dimensions and multiple child psychopathology domains.

Forty years of parenting research have produced consensus regarding the importance of several dimensions of parenting behavior, including behavior control, psychological control, and warmth/support (e.g., Gray & Steinberg, 1999). Yet the precise nature of the relation of these parenting dimensions to child psychopathology remains unclear. For example, there is not yet consensus as to whether parenting behavior dimensions are best considered as categorical parenting styles (e.g., authoritative parenting, authoritarian parenting; Baumrind, 1991) based on simultaneous consideration of multiple dimensions, or as independent, continuous dimensions (e.g., psychological control; behavior control; Barber, 1996).

Underlying the use of parenting style typologies (as opposed to separate dimensions of parenting) are several assumptions about the nature of parenting behaviors, including the belief that (a) parenting behaviors are themselves correlated (e.g., parents who are warm tend to use positive behavior control strategies), and thus parenting behaviors should be considered in clusters rather than separately; and (b) the effects of one type of parenting behavior on children are dependent on the presence or absence of other parenting behaviors (i.e., parenting behaviors have interactive effects on child outcomes), and thus typologies should simultaneously consider multiple parenting behaviors. Although many studies have failed to find interactions among parenting behaviors in the prediction of child psychopathology (e.g., Barber, Olsen, & Shagle, 1994; Garber, Robinson, & Valentiner, 1997), others have found some evidence for interactive relations (e.g., Galambos, Barker, & Almeida et al., 2003; Pettit & Laird, 2002).

As O’Connor (2002) has noted, at the core of this discussion regarding whether parenting dimensions are best considered independently or in clusters is the question as to whether there is specificity in the relation between different parenting dimensions and child outcomes. Most theories linking parenting and child psychopathology posit causal processes wherein specific parenting behaviors influence the development and /or maintenance of specific forms of child psychopathology. For instance, in Patterson’s theory of “coercive cycles” (Patterson, 1982; 1997), parents’ capitulation to children’s tantrums is hypothesized to serve as a negative reinforcer for the child’s tantrums, ultimately teaching the child that oppositional, aggressive behavior will be reinforced, increasing the likelihood the child’s negative behavior will re-occur. The empirical literature, however, suggests that the actual relations between parenting behavior and child psychopathology may be relatively non-specific. In the case of the coercive cycles hypothesis, for instance, several studies (e.g., Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz & Simons, 1994) indicate that coercive processes also may be related to internalizing as well as externalizing problems. O’Connor (2002) concluded that there is only “modest evidence” for specificity.

For several reasons, we believe that there is not yet an adequate body of research is to support (or disconfirm) such a conclusion. First, the parenting literature is vast but relatively few studies have directly assessed specificity of effects. Although it sometimes is possible for quantitative literature reviews to address questions not addressed by the original studies (see e.g., Weisz, Weiss, Han, Granger, & Morten, 1995), methodological characteristics of many studies in the parenting literature may make it impossible to cumulate their findings across studies to assess the specificity of parenting dimensions. For instance, even if certain parenting behaviors have specific relations with child psychopathology, many studies used designs or analytic models that do not take into account correlations among different forms of child psychopathology (e.g., Galambos et al., 2003). Results that appear to indicate non-specific relations to multiple forms of psychopathology (e.g., internalizing and externalizing problems) may actually represent indirect effects of parenting behavior through unassessed covariance between the different forms of child psychopathology. Thus, in the coercive cycles example, it is possible that coercive parenting patterns relate to internalizing problems through the relatively high co-occurrence of internalizing and externalizing problems, and not due to a direct relation between coercive parenting and child internalizing problems. Cross-study comparisons of previous research cannot add clarity since such comparisons cannot control for indirect effects not assessed in the original studies.

A similar potential limitation of cross-study comparisons vis-à-vis identifying specificity is that, as some researchers have noted (e.g., Darling & Steinberg, 1993), past research often has examined only one or two parenting behavior dimensions at a time. Because parents use multiple strategies, the total effect of a particular type of parenting behavior dimension will be a function of the entire repertoire of correlated behaviors used by the parent. Thus, two different parenting behaviors may in actuality have specific, unique effects but because the two parenting behaviors are correlated and these indirect effects are not controlled in the analytic models, they may appear to be non-specific in their relations to different outcomes. Thus, co-occurring parenting behaviors as well as co-occurring psychopathology domains need be controlled in studies in order to assess specificity accurately.

Another potential limitation to reviewing the parenting literature is that effects of at least some parenting behaviors may differ as a function of the interaction task or larger context in which the behavior occurs (e.g., Dadds & Sanders, 1992; Holden & Miller, 1999). Because many studies have examined parent-child interactions in only one interaction task (e.g., Dadds, Sanders, Morrison, & Rebgetz, 1992) or have combined data across different tasks (Ge, Best, Conger, & Simons, 1996), little is known about the relation between parenting behavior in specific tasks and child psychopathology. Insofar as different studies have assessed the same parenting behavior but in different interaction tasks, cross-study comparisons may suggest that these parenting behaviors have non-specific effects when in fact their effects are specific to the particular interaction within which the parenting behavior occurs.

It should be noted that there are at least three ways in which “specificity” might be operationalized. The first focuses on the question of whether a variable has a unique (i.e., direct) effect, or whether a variable’s effect becomes non-significant when indirect relations through other variables are controlled (e.g., Barber, 1996). For example, a parenting behavior dimension might have a direct effect on internalizing problems, but it also is possible that once indirect effects through externalizing problems are controlled, its effects on internalizing problems are no longer significant. This question of unique effects can help clarify whether a particular path or variable is necessary in a causal model. The second operationalization of specificity concerns whether a variable (e.g., low parental warmth) has differential effects on other variables (e.g., internalizing and externalizing problems). For example, given a model (causal or otherwise) wherein a particular parenting behavior was related to both internalizing and externalizing problems, the question might be asked whether the relation between the parenting behavior and internalizing problems was stronger than the relation between the parenting behavior and externalizing problems (assuming relations were in the same direction). This could be done by testing whether the coefficient linking the parenting behavior and internalizing problems differed significantly from the coefficient linking the parenting behavior and externalizing problems (e.g., through the use of a profile analysis; Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996; Timm, 2002). This question can clarify which of several outcomes in a model is more likely, or which of several causes is more important. If the relations between the predictor and outcome differed in direction, the differential effects test would simply assess whether that difference was significant. Finally, although generally not conceptualized as such, interaction effects represent a form of specificity. That is, interaction tests determine whether the effects of one variable are specific to particular levels of a second variable, or general across the levels of the second variable.

The purpose of the present study was to assess the extent to which the relations between parenting behavior dimensions (or “caregiver behavior dimensions” in the case of the present study, since not all primary caregivers assessed were participants’ parents) and child psychopathology are unique, differential, and / or interactive, focusing on (a) multiple parenting behaviors organized into the three often-identified dimensions of behavior control, psychological control, and warmth (e.g., Barber, et al., 1994), (b) the two main broadband domains of child psychopathology (internalizing, externalizing), and (c) the interaction task within which the parenting behavior occurs (i.e., a ‘Conflict Task’ wherein the caregiver and child discussed a conflict, vs. a ‘Close Feelings’ task wherein the caregiver and child discussed times when they felt close to one another). The purpose of the interaction tasks was to provide samples of parenting behavior and then to relate these samples of parenting behaviors to levels of child psychopathology measured more generally than could be done within the specific task interactions.

We hypothesized that there would be an effect of Task, with caregivers using more behavior control in the ‘Conflict Task’ and more psychological control and warmth in the ‘Close Feelings Task.’ We predicted that the relation between parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology would vary by task, with (a) both unique and differential effects for behavior control in relation to externalizing problems in the Conflict Task, but not in the Close Feelings Task; and (b) differential effects for psychological control in relation to internalizing problems in the Close Feelings Task, and (c) across both tasks, warmth would not show specificity as measured either as unique or differential effects in relation to internalizing or externalizing problems. Given inconsistency of previous studies’ results, our parenting behavior dimensions interaction analyses were considered exploratory.

In studies addressing questions such as these, an important consideration is whether a clinic-referred or a non-referred sample should be used. A clinic-referred sample will increase the frequency or mean level of psychopathology in the sample (see e.g., Donenberg & Weisz, 1997) which is valuable because in non-referred samples, most participants will have relatively low problem levels, the distribution of child psychopathology will be significantly skewed (Hartman et al., 1999), and restriction of range will attenuate correlations. Another way of looking at this issue is that in non-referred samples, few subjects will have substantially elevated problem levels.

However, clinic-referred samples have a major drawback in that the selection factors that placed an individual in the sample pool (i.e., the factors that lead parents to seek to clinic referral, such as parental beliefs about the relative seriousness of different forms of child psychopathology; Weisz & Weiss, 1991) are generally unknown and these factors may bias results in unknown ways (Angold & Rutter, 1992). As a consequence, many researchers (e.g., Barber, 1996) have opted to use non-referred samples, despite the above-noted problems. In the present study, we used a modified form of a clinical sample. Our goal was to include children who were experiencing moderate levels of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology yet avoid unknown selection factors inherent with clinic-referred samples. Participants for the present study were part of a larger treatment study of children with concurrent internalizing and externalizing problems (Weiss, Harris, Catron & Han, 2003), selected from public school classrooms based on their assessed levels of psychopathology. This sampling procedure increased the level of psychopathology in the sample while at the same time avoided problems associated with the clinical referral process.

Methods

Participants

Selection and recruitment

The present study’s participants were part of a larger treatment study of children with concurrent internalizing and externalizing problems (Weiss et al., 2003). Data used in the present study were collected prior to assignment to treatment or control group. One hundred and thirteen families were contacted regarding participating in the main treatment research study, and 93 entered the study (i.e., 17% of those contacted declined participation). Of these 93 potential participants in the present study, 70 produced codeable tapes (participants were excluded because of the failure of the tape recorder to function correctly or because of improper placement of the microphone, and one family declined the interaction task). There were no systematic differences in those families whose tapes were inaudible versus those whose tapes were codeable.

Participants were recruited from four elementary schools serving lower-income neighborhoods. Mental health screening data from assessments conducted by the school system at the end of the third grade were used in the first step of the participant selection process. The school provided these data, consisting of teacher, peer, and self-report measures of internalizing and externalizing problems (see Weiss et al., 2003) to the project with identification numbers only (i.e., without names). Each child’s scores on these variables were standardized to the metric of the normative sample, and then combined to produce (a) an externalizing psychopathology score, (b) an internalizing psychopathology score, and (c) an overall psychopathology score, for each informant for each student; thus each child had nine scores. Any child who was at least one standard deviation above the mean on the internalizing, externalizing, and overall psychopathology scores for two of the three informants was eligible for project enrollment. This selection process did not include parent-reports of child psychopathology, which served as the dependent variable in the present study.

Identification numbers were given to the school, who (a) matched the numbers with students’ names, (b) contacted the family, (c) informed them about the project, and (d) requested permission to provide the research project with their contact information. If a family agreed, this information was provided to project staff who telephoned the family and (a) described the project in more detail, (b) obtained verbal consent, and (c) scheduled a home interview. During this visit details of the project were reviewed, informed consent and child assent were obtained, and the first home assessment was conducted. See Weiss et al. (2003) for additional details regarding this selection process.

Participant characteristics

Seventy children and their primary caregivers participated in this study, 64% of the children were male with a mean age of 9.7 years (SD=.59). Reflecting the fact that participating schools served neighborhoods that were predominantly African-American (across the participating schools, 63% of students were African-American), 66% of the sample were African-American and 32% percent Caucasian. Primary caregivers had a mean age of 34.2 years and a mean number of years of education of 12.5. The sample included 64 mothers (91%), 1 father, 1 stepmother, 1 step-father, 2 grandmothers, and 1 grandfather. The median annual family income was $20,000, with 51% of the families headed by a single parent and 26% having two biological parents in the home. For the participants in the present study, T-scores on the parent-report Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991; see below) Internalizing Problems scale ranged from 43 to 79, with a mean of 59.7; T-scores on Externalizing Problems scale ranged from 38 to 81, with a mean of 60.0.

Procedure

After completion of the outcome study’s baseline assessment including the CBCL (Weiss et al., 2003), caregivers and children took part in two audiotaped interactions. Participants were asked to talk for 5 minutes about times they “felt close” to one another, about when they felt close, and what it was like to feel close (“Close Feelings Task”); during the second interaction task, children and their primary caregiver participated in a revealed differences task in which a family issue was discussed about which the participants disagreed (“Conflict Task”; see Reuter & Conger, 1995). Earlier the caregiver and the child independently identified sources of conflict or disagreement (e.g., chores, homework), and a common issue was identified by the interviewer to serve as the starting point for their discussion. The caregiver and child were instructed to discuss the source of conflict and attempt to develop a solution for the conflict. During the tasks, the interviewer stayed at a distance in the room.

Previous research on parent-child interactions has utilized a variety of tasks. The “Conflict Discussion” or “Revealed Differences” task (e.g., Reuter & Conger, 1995) has been used relatively frequently, as have a number of other tasks such as “planning a vacation” (Donenberg & Weisz, 1997) or discussing family activities (Reuter & Conger, 1998). We selected the two tasks for the present study to parallel the internalizing and externalizing psychopathology that was the focus of the study; i.e., the Conflict Discussion focuses on the behavioral conflict that is central to externalizing problems whereas the Close Feelings task focuses on the affect and emotional relationship that is central to internalizing problems. However, both tasks have the potential to elicit caregiver and child responses important to both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology domains since both tasks have the potential to evoke parent and child affect, as well as hostility or relational difficulties.

Measures

Child Psychopathology

Parent-reported child psychopathology data were collected using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL is a widely used, 118-item parent-report measure of child emotional and behavioral problems. Parents respond on a three-point scale as to how much each item describes their child. The CBCL produces two broadband scales (internalizing and externalizing problems) used as indices of psychopathology. CBCL scales average a one-week test-retest reliability of .89 and a correlation of .81 with the Quay and Peterson (1983) Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (Achenbach, 1991).

Parenting Behavior

The Parental Behavior Coding System (PBCS; Caron, Harris, & Weiss, 1999) was used to code the audiotaped interactions. The PBCS is a micro-analytic coding system of 18 parenting behaviors (e.g., threats; positive comments; effective behavior control). The presence or absence of each parenting behavior was coded within 30-second intervals, and these scores were summed across intervals for each parenting behavior. A subset of the 18 behavior codes then were grouped into the three parent/caregiver behavior dimensions consistently identified in studies of parenting behavior (Galambos et al., 2003): (a) psychological control, (b) behavior control, and (c) warmth, with means computed across all the parental behavior codes that contributed to the dimension (i.e., collapsing across specific behaviors and time intervals). Psychological control included use of guilt induction, hostile tone, emotional over-involvement, and manipulative threats (e.g., Barber, Bean, & Erickson, 2002). Behavior control was defined as use of direct behavior control strategies, such as stating a consequence, suggesting alternatives, explaining why rule is enforced, limit setting, and monitoring (e.g., Barber, et al. 1994). Warmth was composed of positive comments about the child as a person or the child’s behavior, affirmations, active speaking during the task, etc. (e.g., Garber, et al., 1997; Reuter & Conger, 1998).

To estimate inter-rater reliability, all tapes were coded by two trained coders, who coded independently; monthly reliability checks were conducted. The intra-class correlations (ICCs; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) across raters ranged from good to excellent. In the Close Feelings Task, ICCs were: .88 for psychological control, .71 for behavior control, and .91 for warmth. In the Conflict Task, the ICCs were: .90 for psychological control, .84 for behavior control, and .90 for warmth. After coding for reliability, parent-child interaction tapes with the largest inconsistencies in scores across raters were recoded by consensus; tapes not recoded had scores were averaged across rater.

Results

Analysis of skewness and kurtosis indicated that no transformations of variables were necessary. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and pearson correlations among gender, ethnicity, parenting dimensions, internalizing and externalizing problems.

| Measure | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. GENDER | - | - | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 2. ETHNICITY | - | - | −.05 | ||||||||

| 3. WM-close task | 1.65 | .92 | .06 | −.00 | |||||||

| 4. WM-conflict task | .94 | .63 | −.17 | .08 | .47*** | ||||||

| 5. BC-close task | −.11 | .64 | .06 | .19 | −.05 | .01 | |||||

| 6. BC-conflict task | .65 | 1.51 | −.25* | .21 | .09 | .32** | .19 | ||||

| 7. PC-close task | .29 | .35 | −.18 | .24* | .16 | .22 | .04 | −.05 | |||

| 8. PC-conflict task | .94 | .92 | −.06 | .29* | .11 | .20 | −.15 | −.23 | .13 | ||

| 9. INT | 59.7 | 7.56 | .24* | .16 | −.24* | −.32** | −.01 | −.04 | −.04 | .23 | |

| 10. EXT | 60.0 | 8.78 | .13 | .14 | −.30* | −.33** | −.25* | −.18 | −.03 | .28* | .76*** |

Note. SEX: 1=female child, 0=male child. WM=warmth. BC=behavioral control. PC=psychological control. EXT=externalizing problems. INT=internalizing problems.

p < .05.

p < .01;

p < .001.

Interaction Task Effects

A within-subjects profile analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996) was used to determine whether there were differences across the two caregiver-child interaction tasks in the relations between (a) the parenting dimensions, and (b) child internalizing and externalizing problems. Two models were tested, one using internalizing problems as a between-subjects factor (i.e., variation on this variable occurred between-subjects), the other using externalizing problems. In both models, Interaction Task and Type of Parenting Behavior Dimension (e.g., warmth) were within-subjects variables (i.e., variation on these factors – Close Feelings Task vs. Conflict Task, and Psychological Control vs. Behavioral Control vs. Warmth, respectively – occurred within each subject).

For internalizing problems, significant effects were found for the main effects (a) of Interaction Task (F[1,68]=10.68, p<.005) and (b) Type of Parenting Behavior Dimension (F[2,136]=40.47, p<.0001), and (c) their interaction (F[2,136]=36.77, p<.0001); because these effects do not involve child psychopathology, results for externalizing problems were essentially identical. The main effects indicated that the amount of control that parents used with their children varied as a function of the (a) interaction task (i.e., contrasts comparing the amount of parental control displayed in the Conflict vs. Close Feelings tasks were significantly related to internalizing and externalizing problems), and (b) type of parental control (i.e., contrasts comparing the amount of Behavior Control vs. Psychological Control vs. Warmth were significantly related to internalizing and externalizing problems). The significant interaction indicated that caregivers emphasized different types of controls in the different interaction tasks. However, for both internalizing and externalizing problems, the interactions between psychopathology and task, and between psychopathology, context, and type of control were non-significant (all p>.10). This indicates that the relation between parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology did not differ significantly as a function of the interaction task in which the parenting behavior dimensions occurred. Because there were no differences in the relation between parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology across tasks, all further analyses were conducted with parenting behavior dimensions averaged across task.

Total effects of parenting behavior dimensions

In the analyses below, parenting behavior dimension was treated as the predictor variable and child psychopathology (internalizing and externalizing problems) as the outcome variable. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, it would be possible to reverse the direction of the variables without changing the results. Hierarchical regression was used to examine the relation of each parenting behavior dimension to child psychopathology while controlling for co-occurring parenting behavior dimensions as well as to determine whether there were interactions among parenting dimensions (Table 2). Significant interactions were described by computing the predicted scores for the outcome variable at high (+1 SD), medium (mean), and low (−1SD) values of the moderators, while holding all other variables in the equations at their mean value (Aiken & West, 1991). Child gender and ethnicity were controlled in the first block; Main effects of parenting behavior dimensions were examined in the second block, with parenting dimension interactions examined in the third block of the regression equations examined herein.

Table 2.

Predicting child psychopathology, co-occurring psychopathology uncontrolled

| D.V. (df error) | Effect | β | ΔR2 | Total R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT (61) | Gender | .31** | ||

| Ethnicity | −.03 | .06** | ||

| W | −.51*** | |||

| PC | .51*** | |||

| BC | .19 | .20*** | ||

| W × BC | .10 | |||

| PC × BC | .22* | |||

| W × PC | −.36*** | .18*** | .44*** | |

| EXT (61) | Gender | .13 | ||

| Ethnicity | .03 | .03 | ||

| W | −.50*** | |||

| PC | .41*** | |||

| BC | −.10 | .23*** | ||

| W × BC | −.01 | |||

| PC × BC | .22* | |||

| W × PC | −.36*** | .13*** | .39*** |

Note. SEX: 0=male child, 1=female. ETHNICITY: 0=African American, 1=Caucasian. WM = warmth. BC=behavioral control. PC=psychological control. Total=total psychopathology score. EXT=externalizing problems. INT=internalizing problems.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

A consistent pattern emerged across the outcome variables for the parenting behavior dimension main effects. Warmth was moderately negatively related to internalizing and externalizing whereas psychological control was moderately positively related to both psychopathology domains. These beta weights are notably stronger than bivariate relations between the individual parenting behavior dimensions and child internalizing and externalizing problems, indicating suppressor effects. This suggests that previous evaluations of these parenting dimensions that did not assess their effects in models including all three parenting dimensions may have underestimated the direct effects of these parenting behavior dimensions on child psychopathology. Behavior control did not have significant effects in either model.

Interactive effects of parenting behaviors

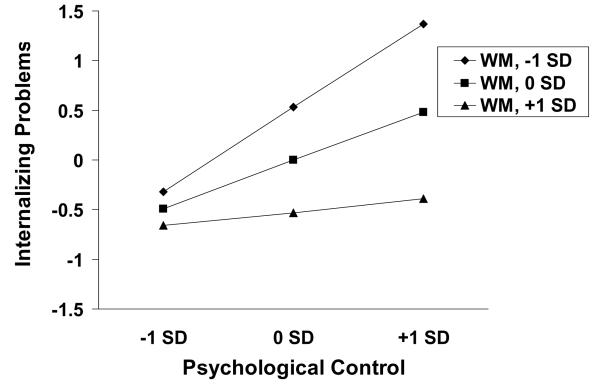

To determine whether each parenting dimension’s relations to psychopathology differed as a function of levels of the other parenting behavior dimensions, we included the two-way interaction terms of centered parenting dimensions (warmth × behavior control, psychological control × behavior control, and psychological control × warmth) in each model. For both outcome variables (see Table 2; third block) two interactions were significant. First, Psychological Control × Warmth was significant for both internalizing and externalizing problems. When high levels of psychological control were coupled with low levels of warmth, children exhibited high levels of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, whereas in the context of high warmth, psychological control was unrelated to level of child problems. Since the interactions were based on continuous variables, we used graphical displays (see Figures 1 and 2) to interpret the results instead of dichotomizing the continuous variables (Cohen & Cohen, 1983).

Figure 1.

Child internalizing problems as a function of parental warmth (WM) and parental psychological control.

Figure 2.

Child externalizing problems as a function of parental warmth (WM) and parental psychological control.

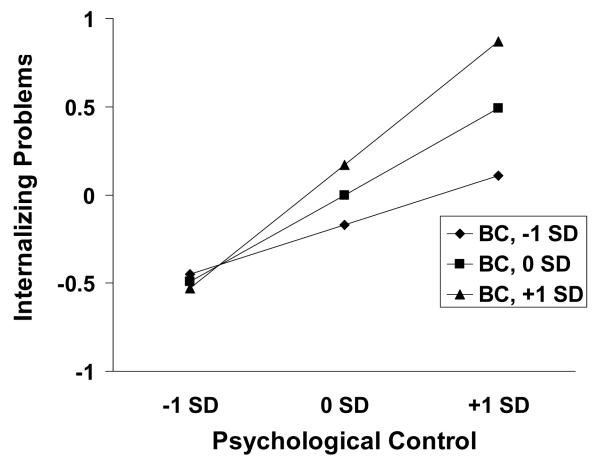

Second, Psychological Control × Behavior Control was significant for child internalizing and externalizing problems. For both psychopathology domains, use of psychological control was related to higher levels of child problems when coupled with high levels of behavior control (see Figures 3 & 4). In the context of low psychological control, however, behavior control was related to lower levels of child externalizing problems, and was unrelated to internalizing problems.

Figure 3.

Child internalizing problems as a function of parental behavior control (BC) and parental psychological control.

Figure 4.

Child externalizing problems as a function of parental behavior control (BC) and parental psychological control.

Unique effects

The next two sets of analyses focused on determining the specificity of the relations between (a) the parenting dimensions and (b) internalizing versus externalizing psychopathology domains, with specificity operationalized as unique effects; i.e., the extent to which parenting behavior dimensions had relations to a child psychopathology domain (e.g., internalizing) when indirect relations through the other parenting behavior dimensions as well as through the other child psychopathology domain (e.g., externalizing) were controlled. Hierarchical regression analyses were used for this purpose with gender and ethnicity controlled in the first block, covaring psychopathology domain in the second block, and parenting behavior dimensions in the third block (Table 3). Analyses initially were conducted including the parenting dimension interactions in the final step (fourth block). However, because none of the interactions were significant across either unique and differential effects analyses, for clarity the models reported do not include the interaction terms.

Table 3.

Testing specificity: Unique effects (hierarchical controlling for co-occurring psychopathology) and Differential Effects (contrast outcome variable).

| D.V. (df error) | Effect | β | ΔR2 | Total R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT (63) | Gender | .20* | ||

| Ethnicity | −.06 | .06* | ||

| EXT | .72*** | .52*** | ||

| W | −.12 | |||

| PC | .17 | |||

| BC | .27** | .06* | .64*** | |

| EXT (63) | Gender | −.09 | ||

| Ethnicity | .07 | .02 | ||

| INT | .72*** | .54*** | ||

| W | −.1o | |||

| PC | .02 | |||

| BC | −.24* | .07* | .64*** | |

| EXT-INT (64) | Gender | −.24* | ||

| Ethnicity | .11 | .02 | ||

| Warmth | .01 | |||

| PC | −.12 | |||

| BC | −.42** | .14* | .16* |

Note. SEX: 1=female child, 0=male child. 0=African American. WM=warmth. BC=behavioral control. PC=psychological control. EXT=externalizing problems. INT=internalizing problems.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

When co-occurring psychopathology was included (i.e., when indirect paths through correlated psychopathology domains were controlled), neither warmth nor psychological control were significant predictors (Table 3). The consistent pattern of results across both internalizing and externalizing problems in the previous analyses (Table 2) suggested a possible lack of unique effects. That is, the fact that warmth and psychological control in the prior analyses predicted internalizing and externalizing problems with nearly identical magnitude and direction suggested that these two parenting dimensions were non-specifically related to psychopathology in general. Behavior control, however, did show a unique relation to both internalizing and externalizing problems. For internalizing problems, higher levels of behavior control were associated with higher reported levels of internalizing problems, controlling for level of externalizing problems and other parenting domains. The opposite was true in the model predicting externalizing problems, with greater use of behavior control related to lower levels of reported externalizing problems, controlling for cooccurring internalizing problems and co-occurring parenting behaviors.

Differential effects

The next analyses focused on differential effects; i.e., determining whether parameter estimates linking parenting behavior dimensions to one child psychopathology domain differed significantly from the parameter estimate linking the parenting behavior to the other psychopathology domain. Profile analysis (Harris, 1985; Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996; Timm, 2002) was used, testing the interaction between a predictor variable (in this case, parenting dimension), and the profile effect (in this case, the contrast between internalizing and externalizing problems). This within subjects test assessed the extent to which the relation between the predictor variable (parenting dimension) differed significantly for the different outcome variables (child psychopathology domain) of which the contrast was comprised (see Weiss, Susser, & Catron, 1998). This analysis is analogous to using equality constraints on two parameter estimates in a path or structural equation model.

In the present study, the contrast of interest was the difference between the externalizing and internalizing variables; any parenting dimension significantly related to this contrast was considered to have a broadband specific relation to childhood psychopathology, showing a differential relation to the two broadband syndromes of internalizing and externalizing problems. Gender and ethnicity were controlled in the first block of this regression analysis. Similar to the findings for the unique effects analyses, neither parental warmth nor psychological control showed differential effects to child internalizing versus externalizing problems (see Table 3, third model). This indicates that although both parenting dimensions predicted both types of psychopathology, there were not differences in the magnitude of the relations across child psychopathology outcomes. However, behavior control showed a differential effect, relating to the externalizing minus internalizing contrast, in a model including all three parenting behavior dimensions, accounting for 16% of the variance; neither warmth nor psychological control were significant in this model (F[5, 62] = 2.40, p<.05). Interpretation of this beta-weight is complicated by the fact that the outcome variable is a difference score: The significant beta could indicate: (a) differential magnitude of the relation between the particular parenting dimension and the two outcomes in the same direction (i.e., either positive or negative), or (b) the parenting dimension significantly relates to the two outcomes in opposite directions. In the case of behavior control, the differential relation reflected behavior control relating in opposite directions to externalizing and internalizing problems.

Discussion

Consistent with past research, the present study found that the three main dimensions of parenting behavior – warmth, psychological control, and behavior control – were related to child internalizing as well as externalizing problems, albeit in different ways. Relations between parenting dimensions and child psychopathology domains varied as a function of level of other parenting dimensions (i.e., moderated effects) and types of statistical effects examined (i.e., unique or differential), with warmth and psychological control related to psychopathology in general but showing neither unique nor differential effects. Behavior control was uniquely and differentially related to both internalizing and externalizing problems. The implication of these findings vis-à-vis the question of how parenting behavior should be analyzed is that independently analyzing parenting dimensions or child psychopathology outcome may result in biased or misleading results, and that it is essential to include multiple parenting domains and multiple psychopathology domains in one’s data collection and statistical models; otherwise, incomplete results that are potentially misleading may be produced.

Based on prior work (e.g., Donenberg & Weisz, 1997; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 2000) suggesting the importance of the specific interaction task, we had anticipated that parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology would show different relations as a function of the context of the interaction task. However, although the level of behavior control and psychological control did vary as a function of task, the relation between the parenting dimensions and child psychopathology did not vary across interaction task. In contrast to parental psychological and behavior control, levels of parental warmth were correlated across tasks, suggesting that although parents’ controlling behaviors were task dependant, their use of warmth was not.

The particulars of our specificity findings (i.e., interactive, unique, and differential effects) have interesting implications regarding processes linking parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology that should be examined in future longitudinal studies. Because our data are cross-sectional both directions of causality must be considered. For instance, similar to Pettit and Laird (2002), we found that higher levels of psychological control were associated with higher externalizing problems only when warmth was low (but c.f. Gray & Steinberg, 1999). From a ‘parent effects’ perspective, this may reflect a compensatory process wherein high warmth compensates or buffers against the negative effects of high psychological control. On the other hand, from a ‘child effects’ perspective, externalizing behaviors could invoke high levels of psychological control only when the caregiver-child relationship is not grounded in warmth or closeness, perhaps because of a buffering effect of the closeness of the relationship on the caregivers’ interpretations of the child’s behavior. This interactive relation held for the prediction of child internalizing problems as well.

Psychological control was most strongly associated with child externalizing and internalizing problems when caregivers also used high levels of behavior control. This combination of high behavior control (conceptualized as a positive socialization strategy) with high psychological control (typically conceptualized as an intrusive parenting strategy) may represent parenting that is too controlling and may result in a child feeling “smothered” and developing internalizing problems (via decreasing self-esteem or personal agency) or feeling frustrated and developing externalizing problems (via hostile social information processing: Gomez, Gomez, DeMello, & Tallent, 2001). On the other hand, child effects processes may be occurring wherein caregivers react to a behaviorally difficult child by resorting to all available means of control, reflecting development of a coercive process (Galambos, et al., 2003; Patterson, 1982; 1997). Although some longitudinal studies suggest caregivers ultimately decrease positive behavior control strategies in response to increasing child deviance (e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2003), use of more negative types of control (i.e., possibly reflected in the joint use of behavioral and psychological control in this study) has been shown to increase with increasing child behavior problems (Scaramella, Conger, Spoth, & Simons, 2002; Stice & Barrera, 1995).

The combination of high levels of psychological control and behavior control was linked to higher levels of both child internalizing and externalizing problems. However, when psychological control was low, the importance of behavior control varied across psychopathology domains: When psychological control was low, the level of behavior control was unrelated to the level of internalizing problems but was negatively related to the level of child externalizing problems. This is not surprising given that behavior control focuses directly on externalizing problems themselves (e.g., rule violating delinquent behavior) or risk factors for externalizing problems (e.g., associating with deviant peers: Scaramella et al., 2002) but does not act directly on internalizing problems.

With regard to unique and differential effects, psychological control and warmth were related to both forms of psychopathology, failing to show either form of specificity. This suggests that there may be overlapping pathways linking these parenting behavior dimensions to child internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, an idea that is consistent with empirical findings (Gray & Steinberg, 1999; Pettit, Laird, Bates, Dodge, & Criss, 2001). One instance of specificity, as measured by both unique and differential effects, involved parental behavior control. Behavior control showed a unique relation to externalizing problems, which suggests a link between these two constructs that is not mediated through other forms of psychopathology. Further, parental behavior control showed a differential relation between child externalizing and internalizing problems, such that as the difference between levels of externalizing and internalizing problems increased the amount of behavior control decreased. Similar to Fauber, Forehand, Thomas and Weirson (1990), when other parenting behavior dimensions were included in models but correlated psychopathology domains were not included, behavior control was not associated with either internalizing or externalizing problems (but c.f., Gray & Steinberg, 1999). Consistent with prior work directly testing unique effects (e.g., Barber, 1996), however, behavior control appears to have a specific relation to both externalizing and internalizing problems. These results highlight the risk of failing to consider cooccurring psychopathology in research designs, with suppressor effects reducing relations between parenting behavior and different child psychopathology domains (see Lilienfeld, 2003).

In regards behavior control’s unique relation to child internalizing problems, there is some reason to believe that the direction of effects may run from parent to child, as it seems relatively unlikely that child internalizing problems (e.g., withdrawal) would cause parents to increase use of behavior control. With regard to behavior control and externalizing problems, however, multiple reinforced processes may underlie these unique and differential relations that warrant further study in longitudinal studies. From a ‘parent effects’ model (or from ‘parent maintenance’ model, since child psychopathology in middle childhood likely is being maintained rather than created by parent behavior), low levels of behavior control could relate to increased child externalizing problems due to increased opportunities to act out without appropriate guidelines for behavior regulation, or increased opportunity to engage with deviant peers (Kim, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1999; Scaramella, et al., 2002). Recent support in the literature, however, has been found for child effects models such that high levels of externalizing problems in children result in decreases in behavior control due to increased parental tolerance or hopelessness regarding the externalizing behavior (Stice & Barrera, 1995). Thus, for this sample behavior control attempts may be more a reaction to earlier externalizing behavior (e.g., delinquency) than vice versa, and changes youth’s behavior in the family context (e.g., being secretive or intimidating) may mediate this relation between delinquency and parental control attempts (i.e., intimidated or worried parents may decrease behavior control attempts; Kerr & Stattin, 2003).

Although behavior control was both differentially and uniquely related to internalizing as well as externalizing problems, it is possible that behavior control (or any parenting behavior) could relate to different forms of child psychopathology uniquely but not differentially, or vice versa. A particular parenting behavior might, for instance, show a direct path of 0.4 to internalizing as well as externalizing problems, thus showing unique but not differential relations to internalizing and externalizing problems. On the other hand, a particular parenting behavior might show a direct path of 0.3 to internalizing and 0.6 to externalizing problems, and if the difference in coefficients were significant then there would be unique as well as differential relations.

This distinction is important because under certain circumstances differential and unique specificity may have different implications. In regards to treatment, for instance, even if a parenting behavior showed an overall / total effect on the intervention’s target problem, if the parenting behavior did not show a unique effect for the target problem area then helping parents/caregivers develop or refine this parenting behavior might not be useful or even necessary; i.e., the lack of a unique effect suggests the parenting behavior is not directly impacting on the target problem area in the child and thus may not be the most useful intervention target. In contrast, lack of a differential relation would not imply that the parenting behavior is unimportant in regards to the different forms of child psychopathology but rather that it is equally important for both problem areas. Thus, when targeting comorbid problems (e.g., Weiss et al., 2003) for instance, finding unique but not differential specificity would suggest that this parenting behavior might be particularly appropriate as an intervention target, since it would be impacting equally on two comorbid problem areas. Information regarding unique and differential effects can help streamline program development, by identifying intervention components that are unnecessary or that may be particularly useful to target.

Finally, in regards to the issue of whether parenting behavior dimensions should be conceptualized as separate dimensions or as parts of categorical parenting styles (e.g., authoritarian, authoritative), our study’s findings suggest support for both perspectives. Although, for example, the interactions between behavior control and psychological control suggest a possible unique combination that could reflect a category similar to an authoriarian parenting style, the specificity findings point to the need to consider the parenting behavior dimensions separately, and that information would be lost by creating subgroups of parenting styles. However, when unique or differential specificity effects were examined, the parenting behavior interactions were no longer significant. Because both unique effects (i.e., suggesting continuous parenting dimensions) and interactive effects (i.e., suggesting possible categorical styles) did not co-exist within models in this study, it would be useful for future studies with larger sample sizes to determine if our findings are reflective of low power or suggest that the interactions and unique / differential effects are tapping a similar phenomenon. Such information would have implications for how we conceptualize, examine, and model parenting behavior dimensions.

Several caveats regarding this study should be noted. First, our sample was relatively small and thus replication with larger samples will be important. Second, the extent to which the behavior displayed by caregivers in the structured audiotaped interactions is representative of their everyday behavior is unclear. The somewhat contrived nature of the tasks may reduce the generalizability of the behavior displayed by participants. However, a study by Dadds and Sanders (1992) reported a significant correlation between parent-child interactions in the lab and behaviors in the home. The fact that our interaction tasks were conducted in a more naturalistic setting than Dadds and Sanders further supports the generalizability of our results. However, our choice to use audiotapes rather than videotapes may have restricted the range of caregiver information we were able to assess from the interactions (e.g., facial expressions). Further, although our 2 coders were reliable with one another, problems of observer drift over time can not be ruled out.

Third, although we controlled for gender and ethnicity in our analyses, we did not examine gender or ethnicity as possible moderators of the relations among parenting dimensions and child psychopathology domains, because our sample size precluded sub-group analyses (Whisman & McClelland, 2005). Some (e.g., Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996) but not all studies have found that effects of certain parenting behaviors vary as a function of ethnicity, and thus our inability to carry out similar analyses may be a limitation to the study. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not provide information regarding the direction of effects. It may be that (a) parenting dimensions cause or perpetuate child psychopathology (e.g., Ge et. al., 1996), (b) child psychopathology elicits certain parenting behavior dimensions (e.g., Bell, 1968), and / or (c) unassessed third variables (e.g., heredity; Deater-Deckard & Plomin, 1999) are responsible for child psychopathology as well as parenting behavior dimensions. In particular with regard to child effects, a number of studies have shown the importance of individual differences in child behavior and temperament (e.g., child negative emotionality; Scaramella & Conger, 2003) in predicting parenting behaviors. Work in this area incorporating specificity models would prove beneficial to our understanding of the findings herein.

Fifth, only caregivers who were interested in participating in a treatment study were involved in this investigation, and our results therefore may not be generalizable to non-treatment samples. In addition, like some other researchers in this area (e.g., Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, Lengua, & Conduct Prevention Research Group, 2000), we intentionally chose participants based on elevated psychopathology scores to ensure that children with a range of severity of psychopathology were included in the study while at the same time avoiding selection problems inherent with clinic-referred samples (Angold & Rutter, 1992). Use of a normal sample would have resulted in a skewed sample with few participants experiencing significant levels of psychopathology. It is possible, however, that our selection process resulted in a restricted range of psychopathology. However, our subject selection was based on teacher-, peer-, and self-report whereas our dependent variable was parent-reported child psychopathology; this resulted in psychopathology scores ranging from one standard deviation below the mean to three standard deviations above the mean, suggesting that if restriction of range did occur, it was not substantial.

Finally, we should note that the relation between internalizing and externalizing problems in our sample was quite substantial. It is possible that the magnitude of this relation was a function of our sample selection procedure, which in turn might suggest limits to the generalizability of our results. However, in a sample of over 1,400 non-referred fourth graders, Cole and Carpentieri (1990) found a correlation of .73 between depression and conduct disorder factors, which suggests that the strong relation between internalizing and externalizing problems that we found in our selected sample probably was not a function of our selection process.

Acknowledgments

Annalise Caron, Division of Clinical and Genetic Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute. Bahr Weiss and Vicki Harris, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University. Tom Catron, Department of Community Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University. This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01-MH54237; R01-MH58275), American Psychological Foundation’s Elizabeth Munsterberg Koppitz Fellowship, and by the Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies. The authors wish to thank the following people: Most importantly, the families and children who participated in the project; Emery Lancaster for her time and diligence in coding the parent-child interactions; and the staff of the Center for Psychotherapy Research in the Vanderbilt Institute of Public Policy Studies for help with data collection.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Rutter M. Effects of age and pubertal status on depression in a large clinical sample. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development. 1996;67:3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Bean RL, Erickson LD. Expanding the study and understanding of psychological control. In: Barber BK, editor. Intrusive Parenting: How Psychological Control affects Children and Adolescents. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2002. pp. 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA, Shagle SC. Associations between parental psychological control and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron AL, Harris VS, Weiss B. Parental Behavior Coding System. Vanderbilt University, Department of Psychology and Human Development; Nashville, TN: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression / correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Carpentieri S. Social status and the comorbidity of child depression and conduct disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:748–757. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family processes, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Sanders MR. Family interaction and child psychopathology: A comparison of two observation strategies. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1992;1:371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Sanders MR, Morrison M, Rebgetz Childhood depression and conduct disorder: II. An analysis of family interaction patterns in the home. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:505–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Plomin R. An adoption study of the etiology of teacher and parent reports of externalizing behavior problems in middle childhood. Child Development. 1999;70:144–154. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Weisz JR. Experimental task and speaker effects on parent-child interactions of aggressive and depressed/anxious children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:367–387. doi: 10.1023/a:1025733023979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber R, Forehand R, Thomas AM, Wierson M. A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child Development. 1990;61:1112–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, Almeida DM. Parents do matter: Trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Development. 2003;74:578–594. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Robinson NS, Valentiner D. The relation between parenting and adolescent depression: Self-worth as a mediator. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:12–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Best KM, Conger RD, Simons RL. Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and co-occurrence of adolescent depressive symptoms and conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:717–731. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Gomez A, DeMello L, Tallent R. Perceived maternal control and support: Effects on hostile biased social information processing and aggression among clinic-referred children with high aggression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2001;42:513–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MR, Steinberg L. Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:574–587. [Google Scholar]

- Harris RJ. A primer of multivariate statistics. 2nd ed Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman CA, Hox J, Auerbach J, Erol N, Foneseca AC, Mellenbergh GJ, Novik TS, Oosterlaan J, Roussos AC, Shalev RS, Zilber N, Sergeant JA. Syndrome dimensions of the Child Behavior Checklist and Teacher Report Form: A critical empirical investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:1095–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Miller PC. Enduring and different: A meta-analysis of the similarity in parents’ child rearing. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:223–254. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s Influence on Family Dynamics. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J,E, Hetherington EM, Reiss D. Associations among family relationships, antisocial peers, and adolescents’ externalizing behaviors: Gender and family type differences. Child Development. 1999;70:1209–1230. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Comorbidity between and within childhood externalizing and internalizing disorders: Reflections and directions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:285–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1023229529866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG. Annotation: The ‘effects’ of parenting reconsidered: Findings, challenges, and applications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:555–572. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. A social learning approach to family intervention III. Coercive family process. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Performance models for parenting: A social integrationist perspective. In: Grusec J, Kuczynski L, editors. Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory. Wiley; New York: 1997. pp. 193–226. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD. Psychological control and monitoring in early adolescence: The role of parental involvement and earlier child adjustment. In: Barber BK, editor. Intrusive Parenting: How Psychological Control affects Children and Adolescents. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2002. pp. 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583–598. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay HC, Peterson DR. Interim manual for the Revised Problem Behavior Checklist. University of Miami; 1983. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter MA, Conger RD. Interaction style, problem solving behavior, and family problem solving effectiveness. Child Development. 1995;66:98–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter MA, Conger RD. Reciprocal influences between parenting and adolescent problem solving behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1470–1482. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children’s negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella L, Conger RD, Spoth R, Simons RL. Evaluation of a social contextual model of delinquency: A cross-study replication. Child Development. 2002;73:175–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. The role of context in the development of psychopathology: A conceptual framework with some speculative propositions. Child Development. 2000;71:66–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M. A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents’ substance sue and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ, Lengua LJ, Conduct Prevention Research Group Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3rd ed Harper Collins; New York City: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Timm NH. Statistics and probability. Springer-Verlag; NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Harris V, Catron T, Han SS. Efficacy of the RECAP intervention program for children with concurrent internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:364–374. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Susser K, Catron T. Common and specific features of childhood psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:118–127. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B. Studying the “referrability” of child clinical problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:266–273. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Han SS, Granger DA, Morten T. Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:450–468. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, McClellend GH. Designing, testing, and interpreting interactions and moderator effects in family research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:111–120. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]