Abstract

Background

Nutrition management of cirrhosis in hospitalized patients is overlooked despite the clinical significance of sarcopenia or loss of muscle mass in cirrhosis. Determining optimal nutrition requirement needs precise measurement of resting energy expenditure (REE) in the cirrhotic patient. Predictive equations are not accurate, and the metabolic cart is expensive and cumbersome. The authors therefore performed a prospective study to examine the feasibility and accuracy of a handheld respiratory calorimeter (HHRC) in quantifying the REE in hospitalized cirrhotic patients not in the intensive care unit.

Materials and Methods

The study was done in 2 phases: in the first phase, the REE of 24 consecutive healthy volunteers was measured using an HHRC in different positions. The objective of this phase was to identify the impact of body and arm position on measured REE. Subsequently, in the second phase of the study, REE was measured using the HHRC and the metabolic cart in 25 consecutive well-characterized, hospitalized cirrhotic patients. The degree of concordance was calculated.

Results

Body position and arm position did not significantly affect the measured REE using HHRC. In patients with cirrhosis, the mean measured REE (kcal/d) using the HHRC was 1453.2 ± 319.3 in the hospital room, 1525.6 ± 305.2 in a quiet environment, and 1553.7 ± 270.6 with the metabolic cart (P > .1). Predicted REE using 2 widely used equations did not correlate either with each other or with the measured REE.

Conclusions

HHRC is a valid, feasible, and rapid method to determine optimal caloric needs in hospitalized cirrhotic patients.

Keywords: calorimetry, calorimetry, indirect, liver diseases, liver cirrhosis

Loss of skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) and loss of fat mass are the major constituents of malnutrition in cirrhosis that adversely affect the survival and the quality of life of these patients. Hospitalization in cirrhosis aggravates the preexisting protein-energy malnutrition with worsening sarcopenia because of suboptimal oral intakes.1–3 Calorie and protein replacement have been considered to be the mainstay of nutrition interventions in cirrhotics.4 The recommendations for dietary nutrition interventions are typically based on predictive equations in a clinical setting.5 However, the accuracy of these equations has been questioned because body composition, physical activity habits, ethnicity, the underlying clinical condition, and metabolic disturbances affect resting energy expenditure (REE) and cannot be factored in as part of the predicted value.6 More precise quantification of REE in cirrhotic patients is recommended to calculate their caloric and protein requirements.7,8 Assessment of energy needs of these patients is challenging due to the effects of the underlying disease as well as the therapeutic interventions on energy expenditure.9–11 An accurate method to determine calorie requirements is to measure REE. The current reference standard for measuring energy expenditure is the use of a metabolic cart.12 In 7 of the major hospitals in the Cleveland region, none of the nutrition departments were routinely quantifying REE in patients with cirrhosis (Peggy Hipskind, personal communication, 2011). The major reasons for this include the large size, lack of portability, and cost of the machine as well as the expertise needed to administer the testing. Therefore, the use of the metabolic cart to quantify REE is not routinely used in hospitalized patients.7 Handheld respiratory calorimeters (HHRCs) have recently been developed to measure energy expenditure. The MedGem (Microlife, Golden, CO) is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved HHRC that measures REE and VO2.13–15 Ease of use, low cost, and shorter time to quantify REE are some of the advantages of the HHRC. Unlike the metabolic cart that requires the patient to be recumbent and covered with the canopy, the HHRC can be used in a sitting position, does not need a canopy, and is relatively easy to perform. Because patients with cirrhosis have difficulty in being in the recumbent position for extended periods of time, an HHRC may be a more convenient and simple method to precisely measure REE that will form the basis of nutrition interventions. The HHRC has been validated to be an accurate and reliable method of quantifying REE in healthy populations.16 However, the HHRC has only been validated in healthy, free-living individuals, and its accuracy has not been established in hospitalized cirrhotics.17 Because the need for precise measurement of REE is greatest in the hospitalized patients to ensure appropriate nutrition interventions,18,19 there is a compelling need for an accurate measure of REE to prevent acute worsening of sarcopenia and malnutrition in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. We therefore conducted a prospective study to determine the feasibility and reliability of the HHRC in patients with cirrhosis admitted to the hospital.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in 2 phases (Figure 1). In the first phase, healthy volunteers were evaluated to determine the optimal position of the subject for measuring REE while holding the HHRC. This was done because when the device is held, the muscles of the arm are active, and this may affect the measured REE. This was reported in a single study in children.20 We then compared the REE obtained from each of the different positions with the Harris-Benedict and the Mifflin–St Jeor equations.17 The metabolic cost of the body position and holding the HHRC was also determined for each individual. The primary objective of this phase of the study was to determine the REE in different arm and body positions using the HHRC in healthy individuals. The secondary objective was to determine feasibility and tolerance of testing. In the second phase of the study, consecutive adult cirrhotic patients who were hospitalized were studied. All of these patients had the REE measured using the HHRC in their hospital room and again in the clinical research unit (CRU) using the HHRC and the metabolic cart. In addition, REE was predicted using the Harris-Benedict and Mifflin–St. Jeor equations in all these participants because these are used most frequently in our clinical practice. For these predictive equations, current weight was used to calculate REE. Even though under ideal conditions, the dry weight would have been a better measure, hospitalized cirrhotics have changes in body composition related to ascites, edema, changes in tissue hydration, and malnutrition.21,22 Therefore, for uniformity, we have elected to use the current weight for these calculations. The primary objective of this phase of the study was to identify if REE measured using HHRC in the patient’s hospital room is accurate by comparing these results with that measured using the metabolic cart in the CRU under optimum conditions. The HHRC and the consumable supplies related to the study were procured using independent grant funds with no commercial support.

Figure 1.

Design of study to determine the impact of arm and body position on measured resting energy expenditure (REE) using the handheld respiratory calorimeter (HHRC) in phase 1 and the validity of the HHRC in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. In phase 1, REE was measured in 4 different positions using the HHRC device in healthy controls. In phase 2 of the study, the REE in hospitalized cirrhotics was quantified using the HHRC in their room as well as in the clinical research unit under ideal conditions. These results were then compared with those obtained using the metabolic cart that was considered the gold standard.

Participants

For the first phase of the study, 27 healthy volunteers were recruited to complete an HHRC reading in 4 different positions. These positions were laying (recumbent with the torso inclined at 30°) or sitting (seated vertically) with the arm holding the device propped with a pillow or unpropped. The study was completed in 24 participants (88% of participants were able to complete all 4 components of the study). These positions were studied in random order with the sequence generated by a randomization table. Participants tolerated the HHRC well, with the majority of them having no complaints (Table 1). In this phase of the study, participants were not assessed using a metabolic cart because the HHRC has been previously validated in healthy individuals and a simultaneous or subsequent measurement after 4 readings from the HHRC would likely alter the measured REE due to the prolonged testing phase.

Table 1.

Patient Tolerance and Feasibility of the Handheld Respiratory Calorimeter (HHRC) in Healthy Participants

| Discomfort With HHRC | After Position 1 | After Position 4 |

|---|---|---|

| None | 16 (66.7) | 15 (62.6) |

| Nose pain/clip pain | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) |

| SOB/difficulty breathing | 2 (8.3) | 0 |

| Study too long | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) |

| Dry mouth | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) |

| Multiple reasons | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) |

Values are presented as No. (%). SOB, shortness of breath.

For the second phase of the study, consecutive hospitalized cirrhotic patients who were able to provide informed consent were included. Patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding, on hemodialysis, on supplemental oxygen, with uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c >12 g/dL), in septic shock or with untreated bacteremia, on intravenous (IV) narcotics, and with hepatic encephalopathy (who could not follow instructions) were excluded. Patients in intensive care units (ICUs) were also excluded. Thirty-three cirrhotic patients satisfied these criteria. Of these, 8 were not able to complete the entire study (discomfort of the HHRC device [n = 5], patients falling asleep during the metabolic cart reading [n = 2], and hypoglycemia requiring oral feeding [n = 1]) and were therefore excluded from the final analysis. A total of 25 cirrhotic patients completed the second phase of the study. The order of obtaining the REE measurements was randomized using random numbers generated from randomization tables.

Clinical and demographic information was obtained for all participants and included age, gender, ethnicity, height, and weight. Adhering to the indirect calorimetry protocol, all participants fasted for at least 4 hours (11.3 ± 0.5 hours in the healthy controls and 13.1 ± 1.5 hours in cirrhotics; P > .1), rested for 10–15 minutes prior to first reading, refrained from exercise for 4 hours, and refrained from caffeine for 4 hours and nicotine for at least 1 hour. In addition, medications and liver disease scores (Model of End-stage Liver Disease [MELD] and Child-Pugh) were obtained for cirrhotic patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and Demographic Features of Cirrhotic Patients

| No. | 25 |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 56.6 ± 8.0 |

| Gender, M:F | 17:8 |

| Ethnicity, No. | |

| White | 19 |

| Black | 2 |

| Hispanic | 4 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis, No. | |

| NASH | 4 |

| Alcoholic | 4 |

| Hepatitis virus | 9 |

| Others | 8 |

| MELD, mean ± SD (range) | 17.4 ± 4.4 (11–28) |

| Child’s score, mean ± SD (range) | 9 ± 1.5 (6–12) |

| Height, in, mean ± SD | 68.5 ± 4.2 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 89.0 ± 20.9 |

| BMI, mean ± SD (range) | 29.6 ± 7.7 (18.3–56.1) |

| Ascites, No. (%) | 17 (68%) |

BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Studies were conducted between 7:00 am and 9:30 am. Morning hours were chosen for ease of adhering to resting and fasting protocols. All participants completed the different components of the study sequentially.

Procedure

The HHRC was calibrated for each participant per the manufacturer’s guidelines prior to each test. The device was placed on a stationary flat surface during calibration. Each participant was tested wearing a nose clip and the disposable mouthpiece in position with a firm seal around the lips. Participants were made comfortable, held the unit in their dominant hand, and were instructed to breathe through the mouthpiece while being motionless. The device collects data from the first breath and continues until a steady VO2 measurement is reached based on a proprietary algorithm. The first 2 minutes permit the participant to be acclimatized and stabilized to the testing protocol. A steady-state VO2 is then obtained during the next 3–8 minutes based on reiterative sets of VO2 in 30 breaths.

For the second phase of the study, each participant’s REE was measured using this device in his or her own hospital room. The participant was then transferred by wheelchair to the CRU, placed in a bed (laying recumbent with the torso reclining at 30°), and allowed to rest for 10 minutes. After recalibrating the device, a second HHRC reading was done in the CRU to compare the REE measured in a busy hospital room with the REE measured in a calm and quiet environment. The metabolic cart used in the CRU was a Vmax Encore (CareFusion, San Diego, CA). After calibrating the metabolic cart, the participant was placed under the canopy and REE measured. The participant was removed from the canopy 3–5 minutes after steady state had been reached or after 20 minutes. Intersubject variability was eliminated by performing all components of the studies sequentially in one sitting. Comparisons were done for measurements within the same participant, and different participants were not compared. Therefore, the metabolic conditions were identical for each participant. The studies were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board, and a written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Equipment

The HHRC is a handheld respiratory calorimeter that measures REE using VO2 and a fixed respiratory quotient (RQ) of .85. The RQ is the ratio of carbon dioxide produced to the volume of oxygen inspired (VCO2/VO2). Respiratory oxygen concentration is based on quenching of ruthenium fluorescence, with the degree of quenching being inversely proportional to the concentration of oxygen present. The volume of inspired and expired air is determined using an ultrasonic sensing technology with transducers placed at each end of a flow tube. The transmission time of the sound waves is proportional to the rate and direction of the air flow. An abbreviated version of the Weir equation, which calculates REE using only oxygen consumption, is used: .23

A metabolic cart is a device used to measure the oxygen consumed and carbon dioxide produced by an individual and then calculates the REE using an abbreviated Weir equation: .24

Impact of Body Position and Holding the HHRC on Measured REE

In the first phase of the study, the metabolic cost of altering the body position from laying to sitting and that of holding the HHRC was calculated as the difference in measured REE for one variable at a time (ie, either the body position or holding the HHRC), and the mean difference was then computed. Specifically, the cost of sitting could be calculated as the difference between REE measured in the sitting position with the arm propped and the REE measured in the laying position with the arm propped. However, the impact of sitting could also be calculated as the difference between the REE measured in the sitting position with the arm not propped holding the HHRC and the REE measured in the laying position with the arm not propped. This gave us 2 metabolic costs for each body and arm position per participant. The mean of these metabolic costs was then calculated.

Bias of Different Methods to Quantify REE

The gold standard for measuring REE was the metabolic cart. The degree of over- or underestimation of REE using different methods was determined both in terms of the absolute differences as well as a percentage of the gold standard that was similar to that reported by other workers.25

Cost Analysis

The cost of measuring REE was calculated based on the consumable items: the mouthpiece and the nose clip for the HHRC and the tubing and gases for the Vmax Encore metabolic cart as well as the prorated cost of the equipment. The HHRC was estimated to be functioning for 1 year based on the warranty period. The life of the metabolic cart was estimated to 5 years of trouble-free, no-cost function. Using these assumptions, the cost of each metabolic cart study was calculated to be $310, and for the HHRC, it was estimated to be $40 per study. This did not include the cost of personnel involved in administering the test, cost of transporting patients to a quiet environment, and inconvenience to the patient during the metabolic cart study that takes significantly more time than HHRC reading. The metabolic cart requires that the patient be evaluated in a quiet environment. Because the hospital floor where cirrhotic patients are admitted is not considered a quiet, stress-free environment, patients need to be transported to an area where the REE can be measured accurately using the metabolic cart. Hence, transportation was taken into consideration when estimating the total cost of quantifying REE.

The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes are numbers assigned to every task and service a medical practitioner may provide in the United States and are used by insurers to determine reimbursement. Using this uniform coding system, we still found major discrepancies in the reimbursements from $250–$625. Because of the wide range, we elected to use our at-cost rate for our calculations.

Statistics

For the first phase of the study in healthy participants, sample size was calculated with the assumption that there would be at least a 20% difference in the measured REE between the HHRC being held actively by the participant or the arm propped up to avoid the effect of arm activity with an α of 5% and a power of 80%. The paired Student t test was used to compare REE using each position. Lin’s concordance was used to examine the degree of agreement between the positions. For the second phase of the study in patients with cirrhosis, quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified and compared using the Student t test. The Bland-Altman analysis was used to assess the agreement between the different methods of measurement of REE. A scatter plot of variable means was plotted on the horizontal axis, with the difference plotted on the vertical axis, which shows the amount of disagreement between the 2 measures. These plots included 95% limits.

The average energy expenditure in patients with cirrhosis of the liver has been reported to be approximately 1561 kcal (range, 1255–1887). Based on a low standard deviation in the measured REE and a high concordance between results obtained by HHRC and the metabolic cart that have been reported,17 the sample size was calculated. A total of 25 patients with cirrhosis would be required to estimate the difference between measures of REE with a 95% confidence interval of ±0.68s (where s is the standard deviation of the difference) for the whole group and within approximately ±0.1s for each stratum.

Results

Impact of Arm Support and Body Position on Measured REE (Phase 1)

The mean age of the 24 healthy volunteers who completed the study was 33.5 ± 11.4 years, with a total of 17 women. The mean total duration of the study, including quantifying REE in all 4 positions, was 52.6 ± 7.3 minutes. The mean REE in the different positions is shown in Figure 2. Even though there was a high degree of correlation between the REE quantified in different positions (Figure 3), measured REE was significantly (P < .05) higher when the arm was not supported independent of the body position. However, the differences in measured REE using the HHRC were not considered biologically significant because they were <5% apart. Among these healthy individuals, there was, however, a significant difference between the predicted and measured REE in all positions (P < .05), and this difference was >5% and therefore considered biologically significant. The mean REE calculated using the predictive equations (Harris-Benedict, Mifflin–St Jeor) was significantly higher than that measured using the HHRC (Figure 2); the predictive equations underestimated the REE in a significantly higher number of participants than they overestimated. The Harris-Benedict underestimated the REE in 21 participants (−243.59 ± 32.33 kcal/d) and overestimated REE in 3 participants (89.6 ± 65.51 kcal/d) compared with the HHRC in the laying propped position. Similar results were observed when the Mifflin–St Jeor equation was compared with the HHRC (underestimated REE in 18 by −214.26 ± 30.71 kcal/d and overestimated in 6 by 88.33 ± 32.24 kcal/d). These suggest that even though the mean REE was higher using the predictive equations, compared with the HHRC, the predictive equations underestimated the REE in a large number of participants.

Figure 2.

Resting energy expenditure (REE) using the handheld respiratory calorimeter in different body positions with and without supporting the arm. The measured REE with the arm propped was lower than that measured with the unpropped arm actively holding the instrument. However, the differences were <5%. The predicted REE was significantly higher than the measured value using either the Harris-Benedict or the Mifflin–St Jeor equation. *P < .05.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman analysis with scatter plot of measured resting energy expenditure (REE) in different positions: (A) sitting propped vs sitting unpropped, (B) laying propped vs laying unpropped, (C) laying unpropped vs sitting unpropped, and (D) laying propped vs sitting propped. Lin’s concordance was found to be high among all 4 positions even though the REE was lowest in the reclined position (laying) with the arm supported (propped).

Using this method, we calculated that metabolic cost (median, first and third quartiles) of sitting compared with the laying position to be 10 (−62.5 to +40) with the arm propped and 5 (−62.5 to +90) kcal/d with the arm unpropped. The metabolic cost of holding the HHRC was 80 (25–130) kcal/d in the sitting position and 60 (7.5–115) kcal/d in the laying position.

Impact of Device Used and Location of Reading on Measured REE (Phase 2)

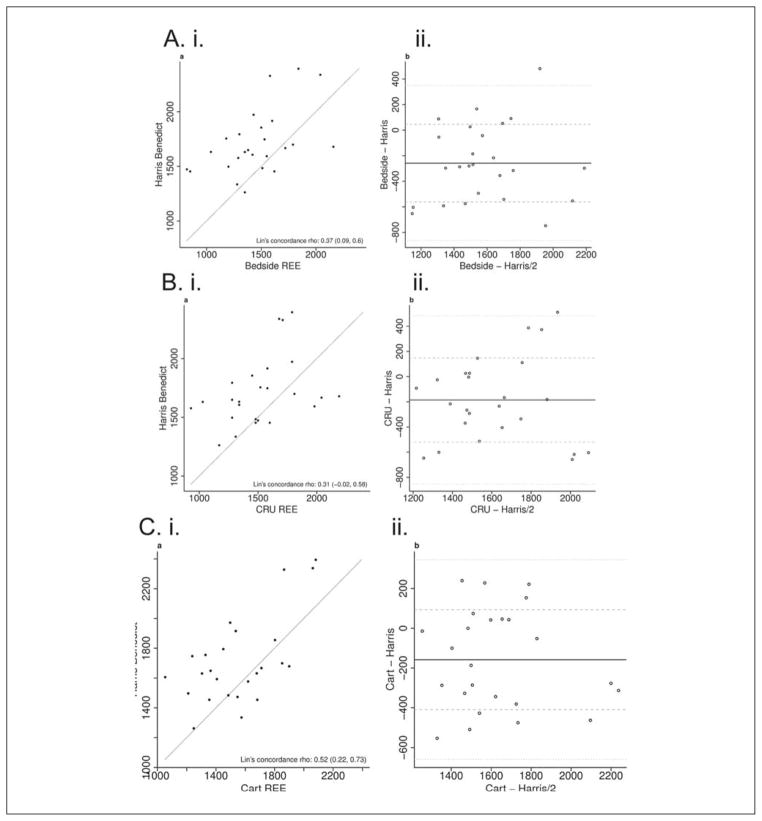

The mean age of the 25 cirrhotic patients was 56.6 ± 8 years, of whom 17 were men and the majority of them were white (76% [Table 3]). All participants were studied in the laying position (recumbent with torso inclined at a 30° angle), having their dominant arm propped when using the HHRC. The mean REE and VO2 from the 3 measurements as well as the predictive equations are shown in Table 4. In cirrhotic patients, the mean difference between the 3 measurements of REE was not statistically significant (HHRC in the hospital room vs CRU: P = .2; HHRC in the hospital room vs metabolic cart in CRU: P = .11; HHRC in CRU vs metabolic cart in CRU: P = .64). When comparing the measurements from the HHRC and the cart with the predictive equations, a significant difference was found (P < .01) with the exception of the REE measured using the HHRC in the CRU compared with the Mifflin–St Jeor equation (P = .7) and the REE measured using the metabolic cart compared with the Mifflin–St Jeor equation (P = .089). The scatter plot of the data and Bland-Altman analyses are shown in Figures 4–6. Panel i for each figure shows the concordance between the REE quantified using 2 different methods. Panel ii shows the Bland-Altman plot to assess the variability at higher or lower values of the measure and the pattern of agreement or disagreement. To determine the bias of the HHRC, we determined absolute differences (Table 5) between the REE measured using the metabolic cart (gold standard) and other methods (HHRC in the room or CRU; predictive equations). It was found that the predictive equations consistently underestimated REE in hospitalized cirrhotics. On the other hand, the HHRC did not have any bias compared with the cart. The Harris-Benedict equation derived mean REE was significantly different from the mean of the measured values. The mean of the measured REE compared with that calculated using the Mifflin–St Jeor equation also differed significantly or showed a trend toward a difference. The absolute differences were then calculated as a percentage of the ideal measurement (metabolic cart or measurements in the CRU). These showed that the HHRC was a reliable measure of REE in cirrhotic patients. Compared with the metabolic cart, the HHRC in the patient’s room underestimated the REE by >20% in 3 (12%) and overestimated the REE in 6 (24%). These were similar to those when the HHRC was used in the CRU. In contrast, both the Harris-Benedict and the Mifflin–St Jeor equations consistently underestimated the REE in a significantly higher number of patients (32%–40%), with overestimation of REE in only a small proportion (4%–12%) of patients.

Table 3.

Laboratory Findings in Cirrhotic Patients

| Mean ± SD (Range) | |

|---|---|

| Serum bilirubin, mg/dL | 6.2 ± 8.0 (0.2–36.7) |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 2.8 ± 0.7 (1.4–4.2) |

| INR | 1.5 ± 0.6 (1–3.8) |

| Serum urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 23.7 ± 14.3 (8–65) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 ± 0.8 (0.5–3.4) |

All values are mean ± standard deviation (range). INR, international normalized ratio.

Table 4.

Measured Resting Energy Expenditure

| Factor | Overall (N = 25) |

|---|---|

| VO2-HHRC in hospital room | 209.6 ± 46.1 |

| REE-HHRC in hospital room | 1453.2 ± 319.3 |

| VO2-CRU HHRC | 220.2 ± 44.0 |

| REE-CRU HHRC | 1525.6 ± 305.2 |

| VO2–metabolic cart | 233.1 ± 45.5 |

| REE–metabolic cart | 1553.7 ± 270.6 |

| Mifflin–St Jeor | 1644.5 ± 253.6 |

| Harris-Benedict | 1711.6 ± 293.9 |

Values presented as Mean ± SD. CRU, clinical research unit; HHRC, handheld respiratory calorimeter device; REE, resting energy expenditure in kcal/d.

Figure 4.

Scatter plots of resting energy expenditure (REE) measured using 2 different methods with Lin’s concordance values shown in panel i. In panel ii, the Bland-Altman plots comparing the REE using 2 methods are shown. The difference in results (y-axis) is plotted against the average magnitude of the result (x-axis). A difference of 0 indicates equivalent results. The dark horizontal reference line is the mean difference in results. The dashed lines are the first and second standard deviation of the difference. The mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown for each panel. (A) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the handheld respiratory calorimeter (HHRC) at the clinical research unit (CRU) and the metabolic cart (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.11–0.73). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE in the CRU using HHRC with the metabolic cart measurement. The mean difference was −28.1 (95% CI, −149.9 to 93.8). (B) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the HHRC bedside and in the CRU (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.80). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing HHRC-measured REE at the bedside with that in the CRU. The mean difference was −72.4 (95% CI, −185.3 to 40.5). (C) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the HHRC at the bedside and the metabolic cart (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.69). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE measured using HHRC at the bedside with the metabolic cart. The mean difference was −100.5 (95% CI, −226.9 to 25.9).

Figure 6.

Scatter plots of resting energy expenditure (REE) measured using 2 different methods with Lin’s concordance values shown in panel i. In panel ii, the Bland-Altman plots comparing the REE using 2 methods are shown. The difference in results (y-axis) is plotted against the average magnitude of the result (x-axis). A difference of 0 indicates equivalent results. The dark horizontal reference line is the mean difference in results. The dashed lines are the first and second standard deviation of the difference. The mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown for each panel. (A) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the handheld respiratory calorimeter (HHRC) at the bedside and that calculated using the Mifflin equation (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.11 to 0.64). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE measured using the HHRC at the bedside with that calculated using the Mifflin–St Jeor equation. The mean difference was −191.3 (95% CI, −309.5 to −73.1). (B) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the HHRC at the CRU and that calculated using the Mifflin–St Jeor equation (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.35; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.62). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE measured using the HHRC in the CRU with that calculated using the Mifflin–St Jeor equation. The mean difference was −118.9 (95% CI, −248.11 to 10.4). (C) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the metabolic cart and that calculated using the Mifflin–St Jeor equation (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.73). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE measured using the metabolic cart with that calculated using the Mifflin–St Jeor equation. The mean difference was −90.8 (95% CI, −196.6 to 15.0).

Table 5.

REE Using Different Devices and Locations

| Mean Difference (95% CI) | Absolute Differences Underpredicted (% Difference) | Absolulte Differences Overpredicted (% Difference) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HHRC in hospital room—HHRC in CRU | −72.4 (−185.3 to 40.5) | −132.5 ± 39.6 (n = 12) (−11.1 ± 3.7) | 261.5 ± 63.1 (n = 13) (16.3 ± 4.1) |

| HHRC in hospital room—metabolic cart | −100.5 (−226.9 to 25.9) | −145.0 ± 38.8 (n = 11) (−11.0 ± 3.3) | 293.4 ± 70.4 (n = 14) (17.6 ± 4.3) |

| HHRC in CRU—metabolic cart | −28.1 (−149.9 to 93.8) | −266.9 ± 47.1 (n = 10) (−19.1 ± 3.5) | 224.7 ± 45.8 (n = 15) (13.5 ± 2.7) |

| HHRC in hospital room—Harris-Benedict | −258.4*** (−383.7 to −133.2) | −387.7 ± 46.6 (n = 19) (−31.0 ± 4.9) | 151.0 ± 68.8 (n = 6) (8.2 ± 3.1) |

| HHRC in CRU—Harris-Benedict | −186.0* (−324.1 to −48.0) | −346.2 ± 51.4 (n = 18) (−25.6 ± 4.4) | 225.8 ± 73.6 (n = 7) (11.4 ± 3.4) |

| Metabolic cart—Harris-Benedict | −158.0** (−261.6 to −54.3) | −312.1 ± 40.0 (n = 16) (−18.6 ± 2.5) | 116.2 ± 31.4 (n = 9) (6.8 ± 1.8) |

| HHRC in hospital room—Mifflin | −191.3** (−309.5 to −73.1) | −333.3 ± 42.5 (n = 18) (−27.5 ± 4.8) | 173.9 ± 52.8 (n = 7) (9.9 ± 2.2) |

| HHRC in CRU—Mifflin | −118.9 (−248.1 to 10.4) | −315.9 ± 40.2 (n = 16) (−23.9 ± 4.0) | 231.3 ± 57.8 (n = 9) (12.4 ± 2.5) |

| Metabolic cart—Mifflin | −90.8 (−196.6 to 15.0) | −285.1 ± 35.9 (n = 14) (−21.1 ± 3.4) | 156.5 ± 35.8 (n = 11) (9.3 ± 21.0) |

Values presented as mean ± SEM. CRU, clinical research unit; HHRC, handheld respiratory calorimeter device; REE, resting energy expenditure in kcal/d.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

P values correspond to paired t tests.

Cost Analysis

The cost of REE measurements using the Vmax Encore metabolic cart was computed to be $310, whereas that of the HHRC was $40 (as described in the “Materials and Methods” section), and the predictive equations were at no cost as part of the nutrition assessment because they were considered to be available from the public domain. The metabolic cart administration required at least 3 training sessions lasting 60 minutes each, whereas the HHRC could be mastered by the investigators in a single session of in-service training lasting about 30 minutes. Thus, the HHRC using the MedGem is about 15% of the cost and is easy to use with significantly less time for learning and application compared with the metabolic cart.

Discussion

This is the first prospective study to demonstrate the feasibility and validity of the HHRC in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. We showed that REE measured by the HHRC is significantly different from that obtained using the Mifflin–St Jeor and Harris-Benedict equations in healthy volunteers. Because the HHRC has been extensively validated in healthy, free-living individuals against the metabolic cart,17 the present studies reiterate that measured REE is superior to that calculated from predictive equations.6 Even though the body and arm position had a statistically significant impact on measured REE using the HHRC, these were not biologically significant. Having established the validity of HHRC and the optimum body and arm position, we also showed that HHRC used in the hospital room in cirrhotic patients yielded results very similar to that obtained using the metabolic cart under optimal conditions. Therefore, the use of HHRC in hospitalized cirrhotics should form part of the nutrition assessment in the management of these patients.

The HHRC is being increasingly used in the measurement of REE because of the lower cost and simplicity of use. Its validity has been extensively studied in free-living individuals.17 One of the considerations when measuring REE using the HHRC is impact of the metabolic cost of body position and holding the instrument on measured REE. Both sitting and holding the instrument in the hand result in muscle contraction that is likely to add to the caloric utilization, leading to an overestimation of the REE. The first phase of our study was designed specifically to address the metabolic cost of body position and holding the instrument. Previous studies have suggested that the caloric cost of sitting is about 60 kcal higher compared with the laying position.20,26 The authors suggested that this may be related to the increased caloric expenditure of sitting and holding the HHRC. They also suggested that further studies with the HHRC are warranted to determine the metabolic cost of subject positioning because this was not part of the original design of their study.20 The first phase of our study was designed to address this issue and showed that the caloric cost of holding the instrument was higher than that related to the body position. However, it must be reiterated that neither the body position nor the propping of the arm had a significant impact on the REE because the differences were <5% of total REE. Although the differences may not be biologically significant, we chose to conduct the second phase of the study using the laying position, torso reclined with the arm propped, because the measured energy expenditure was the least in this position and may therefore be considered closest to the REE. An additional advantage of this was that it mirrored the position of the participant while under the canopy system of the metabolic cart. In contrast to the lack of significant differences between the measured REE in the 4 positions, the predictive equations resulted in higher mean REE than that measured using the HHRC. However, when the biases of these were evaluated, it was observed that the predictive equations underestimated the REE compared with the HHRC in a significantly higher number of participants.

Our observations demonstrating the validity of REE measured using the HHRC in hospitalized cirrhotics is the first of its kind. Nutrition interventions are currently the mainstay for the management of malnutrition in cirrhosis and require quantifying REE to determine optimal caloric replacement.11 Because predictive equations for REE are imprecise and the use of the metabolic cart has limitations, there is a compelling need for an accurate yet simple, economical, and reproducible method to measure REE. Patients with cirrhosis have been classified as hypermetabolic, hypometabolic, and eumetabolic based on the comparison of measured REE with predictive equations.10,11 This has been shown to have prognostic significance.10 We did not classify patients into the individual groups because that was not the goal of this study, but future studies to define patients into these groups will be of great clinical interest. Furthermore, even though patients with cirrhosis have been classified based on the differences between measured REE and predicted REE with wide variation,27,28 our data in both healthy individuals and cirrhotics suggest that the validity of the predictive equations needs to be accurately defined. These have major clinical significance, because studies to date have compared the Harris-Benedict equation with measured REE.10,11 Our data showed that even though the Harris-Benedict and the Mifflin–St Jeor equations yield similar but not identical data, classifying cirrhotics based on comparing their predicted and measured metabolic state may not be as precise as has been believed.10,27 These were reiterated by the Bland-Altman analyses in this study.

Measurement of REE in patients with cirrhosis assists in accurately determining their nutrition needs. Indirect calorimetry is the gold standard for measurement of REE in humans. However, cost is one limitation while using the currently available indirect calorimeters.29 We also discovered other drawbacks to the use of the metabolic cart. The time for which patients needed to be away from other scheduled clinical procedures often exceeded 1 hour and reduced the feasibility of the test. Additional concerns expressed by the patients included their fear of becoming claustrophobic under the canopy, as well as the presence of comorbidities and complications of advanced liver disease that may preclude the prolonged time required for indirect calorimetry using the metabolic cart. Another issue that is specific to cirrhotics is the use of diuretics, which precluded them from completing the study on a metabolic cart (due to possible need for frequent urination that could disrupt the resting period). In contrast, our studies showed that the HHRC is not only a valid method but also significantly more cost-effective than the metabolic cart to quantify REE in hospitalized cirrhotics. The initial cost of the instrument, consumables, time to administer, and the ease of training the evaluator were all significantly lower with the HHRC.

In the present study, major complications such as septic shock, untreated bacteremia, active gastrointestinal bleeding, and renal failure were excluded. This limited their potential to confound the measured REE because these complications are likely to increase the REE. Because it is not possible to quantify the amount of calories absorbed even if REE is measured, it may not be possible to ensure that the entire energy requirements are met in hospitalized patients.

We conclude that the HHRC is a rapid, feasible, and economical method to quantify REE in hospitalized cirrhotic patients not in the ICU. We have not validated this in the out-patient setting because the option of using a metabolic cart is much more feasible in this setting. However, future studies need to be performed to validate the use of HHRC in outpatient cirrhotics also, given the advantages of this method over the traditional open canopy indirect calorimetry.

Figure 5.

Scatter plots of resting energy expenditure (REE) measured using 2 different methods with Lin’s concordance values shown in panel i. In panel ii, the Bland-Altman plots comparing the REE using 2 methods are shown. The difference in results (y-axis) is plotted against the average magnitude of the result (x-axis). A difference of 0 indicates equivalent results. The dark horizontal reference line is the mean difference in results. The dashed lines are the first and second standard deviation of the difference. The mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown for each panel. (A) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the handheld respiratory calorimeter (HHRC) at the bedside and that calculated using the Harris-Benedict equation (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.60). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE measured using the HHRC at the bedside with that calculated using the Harris-Benedict equation. The mean difference was −258.4 (95% CI, −383.7 to −133.2). (B) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the HHRC at the clinical research unit (CRU) and that calculated using the Harris-Benedict equation (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.31; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0.58). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE using the HHRC at the CRU with that calculated using the Harris-Benedict equation. The mean difference was −186.0 (95% CI, −324.1 to −48.0). (C) (i) Scatter plot of REE measured using the metabolic cart and that calculated using the Harris-Benedict equation (Lin’s concordance coefficient = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.73). (ii) Bland-Altman plot comparing REE using the metabolic cart with that calculated using the Harris-Benedict equation. The mean difference was −158.0 (95% CI, −261.6 to −54.3).

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, CTSA 1UL1RR024989, Cleveland, Ohio. SD was supported by NIH RO1 DK083414 and NIH UO1 DK 061732.

References

- 1.Patel MD, Martin FC. Why don’t elderly hospital inpatients eat adequately? J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:227–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02982626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svahn BM, Remberger M, Heijbel M, et al. Case-control comparison of at-home and hospital care for allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: the role of oral nutrition. Transplantation. 2008;85:1000–1007. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816a3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trabal J, Leyes P, Forga MT, Hervas S. Quality of life, dietary intake and nutritional status assessment in hospital admitted cancer patients. Nutr Hosp. 2006;21:505–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plauth M, Cabre E, Riggio O, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsiaousi ET, Hatzitolios AI, Trygonis SK, Savopoulos CG. Malnutrition in end stage liver disease: recommendations and nutritional support. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald A, Hildebrandt L. Comparison of formulaic equations to determine energy expenditure in the critically ill patient. Nutrition. 2003;19:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)01033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campillo B, Richardet JP, Scherman E, Bories PN. Evaluation of nutritional practice in hospitalized cirrhotic patients: results of a prospective study. Nutrition. 2003;19:515–521. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)01071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondrup J, Muller MJ. Energy and protein requirements of patients with chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 1997;27:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guglielmi FW, Panella C, Buda A, et al. Nutritional state and energy balance in cirrhotic patients with or without hypermetabolism: multicentre prospective study by the ‘Nutritional Problems in Gastroenterology’ Section of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller MJ, Bottcher J, Selberg O, et al. Hypermetabolism in clinically stable patients with liver cirrhosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1194–1201. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng S, Plank LD, McCall JL, Gillanders LK, McIlroy K, Gane EJ. Body composition, muscle function, and energy expenditure in patients with liver cirrhosis: a comprehensive study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1257–1266. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selberg O, Bottcher J, Tusch G, Pichlmayr R, Henkel E, Muller MJ. Identification of high- and low-risk patients before liver transplantation: a prospective cohort study of nutritional and metabolic parameters in 150 patients. Hepatology. 1997;25:652–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderegg BA, Worrall C, Barbour E, Simpson KN, Delegge M. Comparison of resting energy expenditure prediction methods with measured resting energy expenditure in obese, hospitalized adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:168–175. doi: 10.1177/0148607108327192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper JA, Watras AC, O’Brien MJ, et al. Assessing validity and reliability of resting metabolic rate in six gas analysis systems. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fares S, Miller MD, Masters S, Crotty M. Measuring energy expenditure in community-dwelling older adults: are portable methods valid and acceptable? J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDoniel SO. Systematic review on use of a handheld indirect calorimeter to assess energy needs in adults and children. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2007;17:491–500. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.17.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hipskind P, Glass C, Charlton D, Nowak D, Dasarathy S. Do handheld calorimeters have a role in assessment of nutrition needs in hospitalized patients? A systematic review of literature. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011;26:426–433. doi: 10.1177/0884533611411272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paauw JD, McCamish MA, Dean RE, Ouellette TR. Assessment of caloric needs in stressed patients. J Am Coll Nutr. 1984;3:51–59. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1984.10720036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles JM. Energy expenditure in hospitalized patients: implications for nutritional support. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:809–816. doi: 10.4065/81.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fields DA, Kearney JT, Copeland KC. MedGem hand-held indirect calorimeter is valid for resting energy expenditure measurement in healthy children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1755–1761. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller MJ, Bottcher J, Selberg O. Energy expenditure and substrate metabolism in liver cirrhosis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17(suppl 3):S102–S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolz C, Raurich JM, Ibanez J, Obrador A, Marse P, Gaya J. Ascites increases the resting energy expenditure in liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:738–744. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)80019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weir JB. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol. 1949;109:1–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham JJ. Body composition as a determinant of energy expenditure: a synthetic review and a proposed general prediction equation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:963–969. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeves MM, Capra S, Bauer J, Davies PS, Battistutta D. Clinical accuracy of the MedGem indirect calorimeter for measuring resting energy expenditure in cancer patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:603–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melanson EL, Coelho LB, Tran ZV, Haugen HA, Kearney JT, Hill JO. Validation of the BodyGem hand-held calorimeter. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1479–1484. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greco AV, Mingrone G, Benedetti G, Capristo E, Tataranni PA, Gasbarrini G. Daily energy and substrate metabolism in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:346–350. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merli M, Riggio O, Romiti A, et al. Basal energy production rate and substrate use in stable cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 1990;12:106–112. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis KA, Kinn T, Esposito TJ, Reed RL, Santaniello JM, Luchette FA. Nutritional gain versus financial gain: the role of metabolic carts in the surgical ICU. J Trauma. 2006;61:1436–1440. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000242269.12534.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]