Abstract

Theories of historical trauma increasingly appear in the literature on individual and community health, especially in relation to racial and ethnic minority populations and groups that experience significant health disparities. As a consequence of this rapid growth, the literature on historical trauma comprises disparate terminology and research approaches. This critical review integrates this literature in order to specify theoretical mechanisms that explain how historical trauma influences the health of individuals and communities. We argue that historical trauma functions as a public narrative for particular groups or communities that connects present-day experiences and circumstances to the trauma so as to influence health. Treating historical trauma as a public narrative shifts the research discourse away from an exclusive search for past causal variables that influence health to identifying how present-day experiences, their corresponding narratives, and their health impacts are connected to public narratives of historical trauma for a particular group or community. We discuss how the connection between historical trauma and present-day experiences, related narratives, and health impacts may function as a source of present-day distress as well as resilience.

Keywords: Historical trauma, personal narratives, public narratives, resilience, community health

Introduction

Historical trauma refers to a complex and collective trauma experienced over time and across generations by a group of people who share an identity, affiliation, or circumstance (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Crawford, 2013; Evans-Campbell, 2008; Gone, 2013). Although historical trauma was originally introduced to describe the experience of children of Holocaust survivors (Kellermann, 2001a), in the past two decades, the term has been applied to numerous colonized indigenous groups throughout the world, as well as African Americans, Armenian refugees, Japanese American survivors of internment camps, Swedish immigrant children whose parents were torture victims, Palestinian youth, the people of Cyprus, Belgians, Cambodians, Israelis, Mexicans and Mexican Americans, Russians, and many other cultural groups and communities that share a history of oppression, victimization, or massive group trauma exposure (Baker & Gippenreiter, 1998; Campbell & Evans-Campbell, 2011; Daud, Skoglund, & Rydelius, 2005; Karenian et al., 2011; Sotero, 2006; Wexler, DiFluvio, & Burke, 2009). Scholars from various disciplines have described the generational aspect of historical trauma as transgenerational, intergenerational, multi-generational, or cross-generational (Bar-On et al., 1998; Kellermann, 2001b), and have introduced concepts, such as soul wound (Duran, 2006; Duran & Duran, 1995) or Post Traumatic Slavery Syndrome (Leary, 2005), to capture the collective experience of trauma by specific cultural groups across generations.

Despite the multitude of terms, historical trauma can be understood as consisting of three primary elements: a “trauma” or wounding; the trauma is shared by a group of people, rather than an individually experienced; the trauma spans multiple generations, such that contemporary members of the affected group may experience trauma-related symptoms without having been present for the past traumatizing event(s). It is distinct from intergenerational trauma in that intergenerational trauma refers to the specific experience of trauma across familial generations, but does not necessarily imply a shared group trauma. Similarly, a collective trauma may not have the generational or historical aspect, though over time may develop into historical trauma.

The widespread interest in historical trauma by scholars across many disciplines presents two unique challenges for this new and rapidly growing area: 1) how to make sense of a diverse empirical literature, and 2) how to integrate that literature with theory so as to advance scientific inquiry. In this critical review and integration, we address these challenges by providing a conceptual framework for understanding the empirical literature on historical trauma, and then specify a theoretical model based on that framework that explains how historical trauma affects present-day health among individuals and communities.

Trauma as Narrative Representation

Central to our perspective is the view that historical trauma functions as a contemporary narrative with personal and public representations in the present. In an influential article published in this journal, Stjepan Meštrović (1985) discussed how early scholarly work on stress and trauma emphasized that trauma is a psychological process independent from the specific traumatic event, that is, as “representation.” He argued that scientific methods should be employed to understand how representations of traumatic experiences impact health (Meštrović, 1985). Subsequent work by medical anthropologist Allan Young further demonstrated how psychological trauma relies on two levels of narrative: 1) an internal logic describing a cause-effect relationship between a past event and present symptoms, and 2) memory as a constructed representation of a traumatic event (Young, 1997, 2004). Young (1997) also showed that trauma varied so dramatically across historical periods and cultures that we cannot assume that past generations represented their traumatic experiences in the same way we would today. Further, because trauma is a representation as opposed to an event, and because we cannot directly know the minds and lives of the past, we cannot assume that our way of responding to negative events is valid for prior generations. Viewing trauma as narrative—representations that contain both personal and public components—directs our focus to the development and impact of present-day representations and their connection to the historic past.

To the extent that historical trauma is a narrative representation, it connects histories of group-experienced traumatic events to present day experiences and contexts, including the contemporary health of a group or community. Thus, historical trauma operates through a layering of narrative turns, including trauma as a concept represented in stories, history as socially endorsed memory, and an internal logic linking history to present suffering or resilience (Crawford, 2013). A narrative framework for historical trauma offers improved conceptual clarity and opportunity for scientific investigation into the relationship between trauma and present-day health by considering the ways in which historical traumas are represented in contemporary individual and community stories. Further, conceptualizing historical trauma as a public narrative avoids problems with projecting contemporary theory back in time, while calling on scholars to engage the full, culture-laden complexity of public narratives in scientific inquiry.

In subsequent sections, we review the existing research on historical trauma across cultures, elaborate on historical trauma as public narrative, and describe the links between psychological health and personal and public narratives. Finally, we present a simplified theoretical model that specifies how historical trauma as a public narrative influences individual and community health.

Existing Research and Theory on Historical Trauma

A number of empirical studies have shown that groups who have histories of trauma are more vulnerable to diminished psychological health in later generations. Kellermann’s (2001a, 2001b) reviews show that children of Holocaust survivors from Israel to Canada are more vulnerable to PTSD, and Barel, Van IJzendoorn, Sagi-Schwartz, and Bakermans-Kranenburg’s (2010) meta-analysis shows that second and third generation offspring of Holocaust survivors display both remarkable resilience and heightened post-traumatic stress symptoms. Daoud, Shankardass, O’Campo, Anderson, and Agbaria (2012) documented lower self-rated health, poorer socio-economic status, and higher stress among Palestinians displaced during the Nakba of 1948 and their descendants in comparison to families who were not displaced. Karenian et al. (2011) found elevated post-traumatic stress symptoms among descendants of the Armenian genocide that, while persistent, seem to be fading with every subsequent generation. Several studies of Canadian First Nations indigenous peoples have found that a family history of forced boarding school attendance and removal from one’s family and community is associated with a number of subsequent behavioral health challenges in later generations, including: increased exposure to sexual violence and involvement in child welfare systems (Pearce et al., 2008), injection drug use (Lemstra, Rogers, Thompson, Moraros, & Buckingham, 2012), current depressive symptoms and increased exposure to trauma (Bombay, Matheson, & Anisman, 2011), and a history of abuse associated with suicidal thoughts and attempts (Elias et al., 2012). Among a sample of North American Plains Indians, Whitbeck, Adams, et al. (2004) have shown that historical trauma affects psychological health through the experience of loss. Their research has demonstrated that, among Native Americans, the frequency of thinking about losses associated with historical traumas: is associated with distressed feelings (Whitbeck, Adams, et al., 2004); mediates the effect of perceived discrimination on alcohol abuse (Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, & Adams, 2004); is distinct from depression (Whitbeck, Walls, Johnson, Morrisseau, & McDougall, 2009); and is a significant source of distress over and above other proximate stressors, such as childhood adversity and negative life events (Walls & Whitbeck, 2011).

The empirical research on historical trauma has followed the growth of theory that links historical trauma to individual and community health. Bar-on et al. (1998) apply attachment theory to explain the preponderance of insecure-ambivalent attachment observed among children of Holocaust survivors, an observation supported in Kellermann’s (2001a, 2001b) reviews of research with this population that showed a predisposition to anxiety-related disorders in later generations. Brave Heart and DeBruyn (1998) point out that government policies toward the Lakota people disrupted culture-based grieving processes, thus resulting in mass unresolved grief. A number of scholars further argue that the violent colonization of the indigenous peoples of the Americas disrupted culture-based protective factors, community systems, and parenting knowledge, thus leading to increased psychosocial risk, inadequate parenting, and health disparities in this population (Campbell & Evans-Campbell, 2011; Crawford, 2013; Gone & Trimble, 2012; Kirmayer, Brass, & Tait, 2000). Walters et al. (2011) also contend that historically experienced traumas may be reflected in heritable biological and epigenetic mechanisms of health risk and illness. And finally, Sotero (2006) argues that, in order for theories of historical trauma to explain the link between present-day health outcomes and past trauma experienced by a particular group, they must be consistent with three overarching theoretical perspectives: 1) psychosocial theory, and specifically, the link between stress and illness; 2) political/economic theory, so as to account for structural determinants of health and illness (e.g., power inequities); and 3) social/ecological systems theory, thus accounting for multi-level influences on health and illness. These extant theories of historical trauma do not explicitly incorporate narrative as a central theoretical framework, but nor are they incompatible with such a framework. A narrative framework for historical trauma asks us to consider more carefully the nature of history.

History is, in part, collective memory, and like memory, is a highly malleable, reconstructive process (see Antze & Lambek, 1996; Young, 2004; Zembylas & Bekerman, 2008). Memories of past traumatic events are constructed within social and cultural contexts, which often determine what is remembered and how it is interpreted. As Foucault (2003) points out, dominant cultures often silence or diminish the value of other cultural groups’ narratives, that is, they disqualify other people’s knowledge and limit what may be discussed publicly. Such struggles for narrative recognition may be an important element of a group’s historical trauma narrative, such as with the struggle of Armenians to have the massacres of their people by Turks during the Ottoman Empire recognized as genocide. Trauma narratives represent an interplay between personal stories and culture and, therefore, are cultural constructions of trauma (Kienzler, 2008). Cultural narratives of trauma may be especially relevant to health, perhaps more so than the actual occurrence of an event, because they frame the psychosocial, political-economic, and social-ecological context within which that event is experienced (Young, 2004). This was evident in a recent study on collective trauma in the Guinean Languette region that documented a relationship between rates of distress and variation in local community narratives of violence and cultural decimation or resilience (Abramowitz, 2005).

Historical Trauma as Public Narrative

By conceptualizing historical trauma as a public narrative we are focusing on narrative accounts that link past experiences of traumatization by a group or community to health over time. Narratives of past traumas and group health over time can be found throughout the world and in reference to a wide diversity of mass-experienced trauma, from a single event, such as a natural disaster (Cox & Perry, 2011), to a recurrent history of oppression and traumatization (Evans-Campbell, 2008). In the latter case, it may be most fruitful to discuss historical trauma in terms of repeated and linked injustices and traumas, some of which date back centuries and others occurring in the present day. Importantly, historical trauma narratives will also vary by person and culture, just as memory and trauma vary across people and cultures (Antze & Lambek, 1996; Young, 1997), and be influenced by the contexts of both local and dominant cultural rules of discourse (Foucault, 2003). This relationship between history, memory, and contemporary contexts highlights the dual nature of historical trauma—on the one hand, historical trauma refers to events and experiences that many people consider traumatic; on the other hand, these events are carried forward through public narratives that not only recount the events but individual and collective responses to them (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Crawford, 2013; Evans-Campbell, 2008).

Although we view historical trauma as narrative, it is important to recognize that these narratives are tied to real injustices or disasters. A narrative conceptualization does not deny the veracity of past traumatic events, but rather redirects one’s focus on how those events are represented and linked to health outcomes today. In this way, historical trauma consists of public narratives that link traumatic events in the historic past to contemporary local contexts so that the trauma becomes part of the contemporary cultural narrative. For example, whereas the fact of boarding schools existence in the history of Native Americans is undisputed, a contemporary narrative explains that the forced removal of children from their families caused the loss of traditional parenting practices among many communities and families, thereby harming the parenting ability of subsequent generations which partially explains behavioral health disparities (Evans-Campbell, Walters, Pearson, & Campbell, 2012). Similarly, without disputing the veracity of the Jewish Holocaust or Palestinian Nakba, we can identify contemporary historical trauma narratives that link these past injustices to present-day social and health conditions—each cultural group views the Holocaust or the Nakba respectively as a great tragedy to befall their people with continued ramifications in contemporary life (Barel et al., 2010; Masalha, 2008). The ways in which people and cultures represent and respond to past traumas become more central than an examination of the facts when we consider historical trauma as narrative.

Understanding historical trauma as a public narrative thus reframes the discussion of historical trauma from a search for historical explanation towards recognition of the contemporary experience of historical trauma and the ways in which current public narratives impact health. A central problem for the scientific study of how the past influence present health is that past events are contestable, as outlined in our discussion on memory and historical narratives, and fundamentally distal to the more proximate factors that influence present health. Whitbeck, Adams, et al. (2004) provide guidance on how one might disentangle proximal versus distal causes when examining the effects of historical trauma. Since one cannot readily measure the impact of past events, sometimes centuries past, on present conditions, they propose examining historical trauma influences on current behavior through one’s psychological experience of historical loss (Whitbeck, Adams, et al., 2004). Specifically, their research has demonstrated empirical links between thinking about historical loss and psychological health indicators, thus emphasizing how the public narrative of historical loss represents a contemporary stressor that has specific and measureable health implications.

Defining Public Narratives

Narratives are stories that string together events to construct meaning and establish discourse (Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007; Riessman, 1993). Through shaping past experience into coherent stories, narratives are the primary means by which people convey contemporary interpretations and aspirations (Bruner, 1991). In particular, people employ narratives to express both individual and collective identities (Wertsch, 2008) and to situate themselves in their social contexts (Hammack, 2008). Personal narratives are stories told by an individual and are unique to that person (Rappaport, 2000), such as a personal account of surviving a car accident. Public narratives differ from personal narratives in as much as they are expressed within public discourse (Ganz, 2011), are indicative of intersubjective understanding (O’Donnell & Tharp, 2012), and are common among a group of people (Rappaport, 2000). Public narratives, thus, are the stories that shape collective memory through reliance on narrative elements such as characters, actions, places, and time (Wertsch, 2008). For example, for one village in the Guinean Languette, the local public narrative recounting the collective memory of attacks by Sierra Leonean Liberation forces includes details regarding who perpetrated the attacks at what sites and when, as well as the armed resistance of village youth, and the period of struggle, poverty, and loss following the attacks (Abramowitz, 2005). We draw a distinction between personal and public by considering whether the story is uniquely told by an individual or whether it exists in a broader social and cultural discourse.

Psychological Health and Public Narratives

A substantial body of research shows a connection between different varieties of narratives and individual and community health. Individuals use narratives to understand traumatic experiences, and often report that they have changed negatively or positively in the aftermath of an experience (McAdams, Reynolds, Lewis, Patten, & Bowman, 2001; Tebes, Irish, Puglisi Vasquez, & Perkins, 2004). A common narrative recounts how one has been irrevocably injured or tainted by adversity (Degloma, 2009). For some, such an account yields a contamination narrative in which positive events are reinterpreted as leading to negative outcomes that result in decrements to well-being (McAdams et al., 2001). For example, the birth of a child may be interpreted as leading to increased stress and social isolation, especially when past trauma experiences are associated with related stressors. For others, the aftermath of trauma leads to a narrative of cognitive transformation or redemption in which a negative life experience is later viewed in positive terms, often after a period of personal struggle (McAdams et al., 2001; Tebes et al., 2004). For example, one may see benefit in becoming more self-reliant after the death of a parent so as to result in a positive reinterpretation of the event’s aftermath, despite the pain caused by the loss. In contrast to contamination narratives, redemption and cognitive transformation narratives are positively associated with well-being and resilience (McAdams et al., 2001; Tebes et al., 2004).

Such personal narratives are contextualized within public narratives that inform how adversity is viewed within the broader culture or by a specific cultural group (Pals & McAdams, 2004). Public narratives may frame how post-traumatic growth, as one example, is even possible within a given socio-cultural context (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Affiliation with group identity and knowledge of the narratives of that group can be a source of resilience for marginalized groups. For example, for indigenous youth and sexual minority youth, group affiliation can encourage a sense of participation in a political struggle evidencing collective strength (Wexler et al., 2009). Resilience in response to adversity and trauma is, in this way, a process in negotiation with influential public narratives such as those conveying group histories of trauma and survival. Just as individuals express resilience through narratives of transformation following traumatic events (McAdams et al., 2001; Tebes et al., 2004), so too do groups and communities represent group resilience in narratives of historical trauma (Crawford, 2013; Denham, 2008; Wexler et al., 2009). Denham (2008) illustrates this effectively by tracing how narrative frames family identity and resilience strategies through four generations of an American Indian family. Family and public narratives, hence, influence the formation of personal narratives, the interpretation of one’s contexts, and the response to personal and collective traumas.

Psychological well-being is related to one’s ability to process narratives and form coherent life stories and interpretations (Pals, 2006; Ville & Khlat, 2006). For example, the ability to develop autobiographical coherence linking one’s sense of self to the past and future, referred to as self-continuity, is predictive of suicide risk (Chandler, 1994). Like self-continuity, Chandler and Lalonde (2009) have shown how cultural-continuity—the degree to which a community engages in actions symbolic of their sense of community as a cultural group—functions as a protective factor and moderator of behavioral health problems among some indigenous Canadian communities. Historical trauma that results from colonization may lead to diminished cultural continuity, which may lead to limited collective action to preserve and advance a cultural legacy (Chandler & Lalonde, 2009). Conversely, narratives of continuity and cultural revitalization promote resiliency (Kirmayer, Dandeneau, Marshall, Phillips, & Williamson, 2011).

Strong cultural identity may be emblematic of public resilience in the face of historical trauma (Crawford, 2013; Gone, 2013). For example, Taylor and Usborne (2010) argue that reconstruction of a strong cultural identity following collective trauma, such as war or disaster, is critical in subsequent individual and community well-being. Their research has shown that clarity in one’s cultural identity predicts personal well-being and that clarity in one’s self-concept mediates this relationship across diverse cultures (Usborne & Taylor, 2010). Furthermore, cultural identity represents the interaction between public norms and self-concept readily expressed in narratives (Gone, Miller, & Rappaport, 1999). International research demonstrates that, across many cultures, family and community narratives contextualize an intergenerational self-concept that serves an important protective role, such as for adolescents (Fivush, Habermas, Waters, & Zaman, 2011) or among marginalized groups who may face daily discrimination (Wexler et al., 2009). Denham (2008) and Crawford (2013) both emphasize how for indigenous people in North America family narratives of historical trauma play a central role in how children situate themselves with respect to adversity and resilience.

A Narrative Model for Understanding the Impact of Historical Trauma on Health

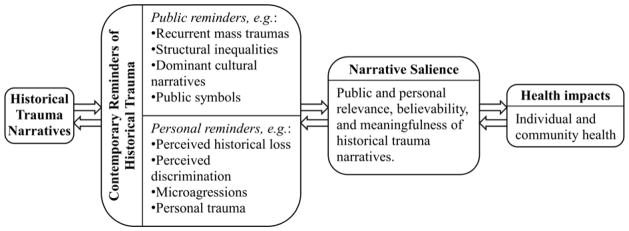

Figure 1 presents a narrative model that specifies how public narratives of historical trauma impact health. As shown, the model specifies successive recursive stages beginning with public narratives of historical trauma that frame contemporary reminders of past collective trauma for a particular group or community. These contemporary reminders influence how salient the narrative is to a person or group; conversely, the salience of the narrative to the individual is critical in determining whether an experience will be interpreted as a reminder of historical trauma(s) or not. Narrative salience also influences whether the narrative will have health implications. Similarly, health status influences the salience of historical trauma narratives; for example, if a person struggles with health outcomes that are attributed to a public narrative of historical trauma, then that narrative is more likely to be seen as relevant to one’s life. Our narrative model of historical trauma is heuristic in that it emphasizes the possible recursive influences between historical trauma narratives, contemporary reminders of that trauma, narrative salience of the trauma within personal and public contexts, and health impacts. We provide a brief description of each component of the model below.

Figure 1.

Narrative Model of How Historical Trauma Impacts Health: Public narratives connect historical traumas to health impacts through public and personal contemporary reminders and the degree of narrative salience. Each stage of the narrative model is recursively influential of the connecting stages.

Historical Trauma Narratives

The left side of Figure 1 depicts historical trauma narratives, that is, public narratives that are present-day, culturally-constructed accounts for a particular group. These narratives link the historical past through meaning-making to contemporary circumstances (Crawford, 2013; Gone, 2013) as depicted in subsequent stages in the model. Following from Wertsch (2008), these stories shape the collective memories of group traumas in the sense that they are stories collectively told, received, interpreted, and re-told—historical trauma narratives are the mechanisms by which memories of historical traumas are shaped and conveyed.

Contemporary Reminders of Historical Trauma

A strict definition of narrative requires a narrator telling the story; however, narratives as such are not the only mechanism by which information on historical traumas are communicated. For example, photography provides powerful visual representations that can serve as reminders of past atrocities (Sontag, 2003). Such contemporary reminders contextualize one’s lived-experience and interpretation of historical traumas. Research with children in Russia showed that situational reminders of trauma, such as walking past shelled buildings or encountering memorials at school, were found to be the greatest source of distress for the children (Scrimin et al., 2011). Similarly, Layne et al. (2010) identified general trauma reminders, such as the news, as the strongest mediator between war trauma exposure and PTSD and functional impairment among Bosnian children. Whitbeck, Adams et al.’s (2004) measure of historical loss exemplifies this process within the context of historical trauma, whereby contemporary contexts and experiences provide reminders of the historical losses. Conversely, reburial ceremonies serve as public symbols that not only highlight the past trauma, but may also promote healing and resilience (Eppel, 2002; Honwana, 1997; Pollack, 2003). Similar to Scrimin et al.’s (2011) distinction between external (e.g., situational and media) and internal (e.g., bodily sensations and affective states) reminders, we divide historical trauma reminders into public and personal reminders.

Public reminders are publically available or experienced events, symbols, contexts, systems, and structures that serve to remind people of historical trauma narratives, such as a new event similar to the past traumatic events, media-portrayed stereotypes, lack of resources, contaminated living environments, and pervasive poverty. Aboriginal reservations and decaying urban environments are examples of structural and physical contexts that can provide daily reminders of historic processes of loss, marginalization, discrimination, and trauma: “An empty city lot is not just the rubble of a razed building, but for the people who have seen it decay it is haunted by memories of the past” (Simms, 2008, p. 88). Also, dominant cultures often perpetuate oppressive public narratives about marginalized groups through media and other public communications, acts, and symbols (Rappaport, 2000), such as Native American sports mascots (Fryberg, Markus, Oyserman, & Stone, 2008).

Personal reminders are individually experienced and relate to historical trauma through an individual’s personal narratives. Examples of personal reminders are perceived discrimination, personal life difficulties, personal trauma experiences, and microaggressions (Sue et al., 2007). As Sue et al. (2007) have noted: “…microagressions are brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults” (p. 273). The extensive research on microaggressions provides powerful examples of how daily indignities are often embedded in narratives of historical oppression and trauma so as to serve as reminders and continuations of past oppression and trauma (Michaels, 2010).

Narrative Salience

Figure 1 also depicts how historical trauma narratives may be more or less salient to an individual or community. Should a person not experience nor perceive any present impact of historical trauma, a narrative of trauma will not have as much meaning to them, even if they are aware of that history. Present conditions and experiences are what make historical trauma narratives relevant to the present and future. Conversely, if a historical trauma narrative is highly salient and accessible to an individual, present conditions and daily indignities also become more readily apparent as part of the historical trauma narrative. Just as dominant cultural narratives serve as reminders of historical traumas, family and community narratives of resilience, action, and aspiration can provide a counter-weight to oppressive dominant cultural narratives (Rappaport & Simkins, 1991). Symbols of marginalization bring to life the traumas in historical trauma narratives (Evans-Campbell, 2008; Simms, 2008), whereas symbols of resistance and persistence bring to life messages of resilience and well-being (Denham, 2008; Fullilove, 1996).

Health Impacts

Finally, the figure also shows how narrative salience influences health impacts. Although Brave Heart (2003) emphasizes psychological distress as a common historical trauma response, as noted previously, other scholars have identified a range of negative health outcomes in response to historical trauma. For example, authors working with diverse populations throughout the world link historical traumas to such contemporary sequelae as predisposition to PTSD (Karenian et al., 2011; Kellermann, 2001b); symptoms of anxiety and depression, with a preponderance of shame and fear (Carolina Lopez, 2011; Evans-Campbell, 2008; Whitbeck et al., 2009); and disruptions to family and parent-child relationships (Bar-On et al., 1998; Campbell & Evans-Campbell, 2011). Similarly, numerous authors use historical trauma as an explanatory framework for understanding a wide-range of health disparities with psychological, social, and biological mechanisms (Crawford, 2013; Daley, 2006; Gone & Trimble, 2012; Sotero, 2006; Walters et al., 2011). Despite this range of potential health impacts, Gone (2013) emphasizes that the development of the notion of historical trauma originates out of the psychological literature, and therefore most discussions of historical trauma preference negative behavioral health impacts. Further, as summarized earlier, health impacts may exemplify wound and survival, trauma and resilience (Crawford, 2013; Denham, 2008).

Illustrations of the Model

Narratives of loss and resilience

Historical trauma narratives do not always offer a clear path to either wounding or resilience, but instead may indicate both of these responses simultaneously. For example, among many indigenous groups around the world, the history of being colonized forms a common narrative that includes being displaced from traditional land and resources, physically and culturally slaughtered, and portrayed by the dominant culture as uncivilized and less evolved (Duran, 2006). This narrative presents a history of trauma, including disease, warfare, colonization, cultural genocide, and poverty, yet it is also a story of ongoing resistance (Campbell & Evans-Campbell, 2011)—it is a history of devastation and survival. Native American reservations in the U.S. and the coerced resettlement of Inuit into government towns in Canada serve as powerful examples of how historical trauma narratives can simultaneously manifest a sense of loss and resilience. This history carries a legacy of imprisonment—with reservations and government settlements serving as ongoing symbols of confinement and loss (Whitbeck, Adams, et al., 2004). Conversely, these communities are also sites of resilience, where indigenous peoples maintain traditional family structures and provide rich enculturation (Walters, Simoni, & Evans-Campbell, 2002). Thus, reservations and government settlements serve a dual function—as reminders of loss as well as places that sustain cultural identity and continuity.

A similar narrative of loss and resilience is found in Abramowitz’s (2005) description of how the public narratives of communities in the Guinean Languette after attacks on their villages resulted in varying post-traumatic symptoms. Those villages that created narratives of group trauma that stressed community persistence and the survival of cultural systems had lower rates of post-traumatic symptoms; in contrast, villages with public narratives that emphasized the destruction of the community’s local moral world exhibited higher post-conflict symptoms (Abramowitz, 2005). This example also illustrates two related observations about narratives of loss and resilience: 1) how the wide variation in public narratives about trauma may result in markedly varying health impacts, and 2) how varying health impacts may be observed despite common traumatic experiences.

Examples of public narratives emblematic of loss and resilience are also evident in the experiences of other historically oppressed cultural groups, including descendants of the Armenian genocide during the Ottoman Empire, descendants of Stalinist persecution in Russian, African American, and aboriginal or indigenous peoples across the world. It is not uncommon for these narratives to include experiences of genocide, forced relocation, enslavement, and ongoing discrimination and marginalization; often alongside narratives of resistance, survival, hope, and resilience (Baker & Gippenreiter, 1998; Evans-Campbell, 2008; Fullilove, 2005; Karenian et al., 2011; Kienzler, 2008; Pollack, 2003; Wexler et al., 2009).

Historical trauma narratives response to disaster

Although historical trauma has mostly been developed to explain the experiences of historically marginalized ethnic groups, the construct is also relevant to understanding individual and community health for groups who have experienced a natural disaster. As Cox and Perry (2011) note in describing how a large wildfire in British Columbia fundamentally altered the community psyche of the two towns most damaged by the fire, place-based traumas also engender public narratives that can impact health. Cox and Perry (2011) show how narratives portraying positive outcomes, such as strengthened sense of community, as well as negative ones, such as feelings of anxiety towards the stability and safety of place, were evident following this disaster. They also show how each of these narratives were related to people’s sense of place. In another example, Long and Wong (2012) describe how the tension between national and local sense of recovery time following the Wenchuan earthquake in China exacerbated a sense of communal trauma. Instead of allowing community members to recover from this disaster at a pace that accommodated their personal and public narratives, members were deluged with national support and public expectations for a speedy recovery that conflicted with these narratives, thus increasing negative health impacts following the disaster. Although these examples are not intergenerational, they illustrate how a place-based trauma can remain part of a community’s cultural identity through a prevailing public narrative of loss or resilience.

Place-based historical trauma narratives can also encode resilience, as is evident by public responses to the great Chicago fire of 1871, which decimated the new city but fostered an altered public identity for its surviving residents and subsequent generations. Many Chicagoans take pride in referring to Chicago as “the second city” because it depicts how the city was rebuilt using brick (rather than wood) following the great fire, how it “[rose] from [its] ashes, a greater city than before” (Shaw, 1921, p. 177). Not only is the narrative one of resilience and thriving, but the mostly brick buildings throughout Chicago serve as a contemporary reminder that heightens the narrative salience of “the second city” and the resilience of its inhabitants.

As Pollack (2003) notes based on his research in Bosnia-Herzegovina, mass trauma experiences can damage people’s relationships to place, but social acts and symbols that re-narrate the connection between physical and social environments can counteract the negative consequences of trauma. Regardless of whether the past traumas are felt based on place, ethnicity, or other social, cultural, or contextual groupings, the public narratives created in response to trauma influence one’s sense of identity.

Conclusion

History provides a narrative context within which contemporary social issues are interpreted. By incorporating a rich understanding of community or group history into social science research on health, we improve the local relevance and responsiveness of research findings and enhance the ability of interventions to leverage community-level and culturally-relevant strategies and variables (Trickett et al., 2011). Should the history contain trauma, the questions become in what ways the historical traumas may or may not be present or impactful and how we might as people and communities respond to these histories in order to promote resilience.

Present-day political forces are increasingly calling for dominant cultures to apologize for historical traumas and document the “truth” of the traumas. In theory, truth commissions promise to repair damage of past abuses through rhetorical strategies that change the dominant cultural narrative to an admission of guilt and wrong doing (Edwards, 2010). Yet, research on the impact of truth commissions is mixed. Evidence from the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission suggests that the commission improved general knowledge but had little to no impact on participant well-being (Kaminer, Stein, Mbanga, & Zungu-Dirwayi, 2001; Stein et al., 2008). Miller (2006) argues that for Canadian First Nations the social-political forms of these apologies may be incongruous with First Nations cultural practices and expectations of reconciliation, thereby limiting their benefit for the aggrieved cultures while benefiting (yet again) the dominant culture. The politics of apology and recognition are thorny—the “political economy of trauma” may do more to benefit the dominant cultures who are apologizing, maintaining their dominance and power, or may help usher in a new period of greater equality (James, 2004). We argue that studying narratives of historical trauma can help disentangle the ways in which contemporary actions perpetrate or repair historical wounds.

Our critical review of historical trauma as a public narrative offers a framework for analyzing how historical traumas are relayed and connected to present-day contexts and health outcomes. Public narratives of historical trauma interact with contemporary reminders of these stories. The reminders serve to make the public narrative more or less salient to particular individuals, families, groups, and communities. The degree of narrative salience, in turn, influences the interpretation of an historical trauma response that manifests as a health impact. Importantly, we suggest that these linkages are recursive, that is, they operate in both directions such that the historical trauma narratives and health impacts mutually influence one another.

At the heart of our review is the conviction that research into historical trauma should remain trained on present-day factors. We believe there are two critical reasons for this. First, we cannot go back in time to document what precisely happened in the past; our knowledge of the past is contained in narrative. And second, as Young (1997) shows, trauma is a present day construct based on contemporary modes of representation and interpretation. Therefore, since we cannot assume that our notions of trauma can be validly projected back through time, our efforts should focus on how the panoply of social science research methods can seek to understand and explain how present day historical trauma narratives impact health.

We view our proposed narrative model as a heuristic for conducting such research, and believe it is relevant to the many social science disciplines currently engaged in studying historical trauma. We also believe that narrative methods are essential to documenting the processes that link public narratives of historical trauma to health outcomes, including experiences of contemporary reminders and the salience given to specific narratives. However, we also believe that a range of mixed methods (Tebes, 2012) are essential to confirm, elucidate, or alter stages described in the model. Research with specific cultural groups is also critical to indentify locally relevant reminders that serve as mediators and moderators of health outcomes, such a sense of historical loss (Whitbeck, Adams, et al., 2004). It is also critical to consider historical trauma as a potential source of both distress and resilience. Research should seek to disentangle how, for whom, when, and where positive sequelae can develop following mass trauma exposure. By studying contemporary experiences of mass trauma and the public narratives that communities generate following trauma, we can better understand how to address historical trauma narratives to enhance community health. In particular, consideration of historical trauma narratives requires attention to the social ecology of history, trauma, and identity for a given population. Historical trauma narratives most likely vary in individual, family, community, and dominant cultural narratives. Disentangling how these differences influence individual and community health is crucial to identifying intervention strategies to promote resilience within the context of historical trauma.

Finally, we believe the narrative model of historical trauma proposed addresses a number of weaknesses of existing historical trauma theories. Green and Darity (2010) warn that current theories of historical trauma fail to account for the effects of daily indignities and make problematic assumptions about marginalized populations. Our proposed model effectively addresses these issues through its emphasis on contemporary reminders and its focus on personal and public salience. The model also provides a basis for understanding individual and community level differences in health outcomes following trauma, since historical traumas are represented differently across individuals, families, populations, and contexts. A narrative approach addresses this concern by requiring careful consideration of individual and collective stories and their integration with contemporary cultural representations and contexts.

Appadurai (2004) posits that culture, and by extension cultural identity, not only refers to past traditions and present norms, but also to a future-oriented capacity to aspire. Public narratives frame how we feel about the world and either inspire action or, as with hopelessness, inhibit it (Ganz, 2011). For cultural groups with significant shared histories of trauma and who experience present-day marginalization, such as many indigenous peoples across the world, a narrative of historical trauma may be a highly salient factor that sustains emotional and psychological wounds, thus functioning as a cultural narrative that inhibits psychological growth and collective aspiration (Chandler & Lalonde, 2009; Crawford, 2013; Gone, 2013). In contrast, historical trauma narratives may also sustain resiliency in response to the ongoing oppression or wounding, as evidenced by family histories of survival (Denham, 2008). The model proposed here provides a means for examining systematically the conditions under which each of these health outcomes are likely to occur; that is, for identifying how historical trauma can have lasting and damaging impacts on health but also be the nexus of group- or community-wide transformation and resilience.

Research highlights.

Historical trauma is a promising but inadequately conceptualized area of research.

A wide variety of research shows the short- and long-term health impact of trauma.

Historical trauma functions a public narrative for particular groups or communities.

We offer a model of historical trauma as present-day narrative that impacts health.

Historical trauma narratives are a source of present-day distress and resilience.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) postdoctoral training program in substance abuse prevention research (T32 DA 019426) to the senior author in support of the lead author, and a Yale Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Scholar program award (K12HD066065) in support of the second author. The authors acknowledge comments made about this manuscript by the Investigators Lab Group of the Division of Prevention and Community Research, Yale University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nathaniel Vincent Mohatt, Email: nathaniel.mohatt@yale.edu.

Azure B. Thompson, Email: azure.thompson@yale.edu.

Nghi D. Thai, Email: thaingd@mail.ccsu.edu.

Jacob Kraemer Tebes, Email: jacob.tebes@yale.edu.

References

- Abramowitz SA. The poor have become rich, and the rich have become poor: Collective trauma in the Guinean Languette. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(10):2106–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antze P, Lambek M. Tense past: Cultural essays in trauma and memory. New York, NY: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai A. Culture and the terms of recognition: The capacity to aspire. In: Rao V, Walton M, editors. Culture and Public Action. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2004. pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Baker KG, Gippenreiter JB. Stalin’s Purge and its impact on Russian families. In: Danieli Y, editor. International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 403–434. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On D, Eland J, Kleber RJ, Krell R, Moore Y, Sagi A, van Ijzendoorn MH. Multigenerational perspectives on coping with the Holocaust experience: An attachment perspective for understanding the developmental sequelae of trauma across generations. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22(2):315–338. [Google Scholar]

- Barel E, Van IJzendoorn MH, Sagi-Schwartz A, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Surviving the Holocaust: A meta-analysis of the long-term sequelae of a genocide. Psychological bulletin. 2010;136(5):677. doi: 10.1037/a0020339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The impact of stressors on second generation Indian residential school survivors. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2011;48(4):367–391. doi: 10.1177/1363461511410240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH. The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: a Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. The narrative construction of reality. Critical inquiry. 1991;18(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CD, Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma and Native American child development and mental health: An overview. In: Sarche M, Spicer P, Farrell P, Fitzgerald HE, editors. American Indian and Alaska Native Children and Mental Health: Development, Context, Prevention, and Treatment. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger; 2011. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carolina Lopez C. The struggle for wholeness: addressing individual and collective trauma in violence-ridden societies. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2011;7(5):300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ. Self-continuity in suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescents. New Directions in Child Development. 1994;(64):55–70. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219946406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE. Cultural continuity as a moderator of suicide risk among Canada’s First Nations. In: Kirmayer LK, Valaskakis GG, editors. Healing Traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancoover, BC: UBC Press; 2009. pp. 221–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cox RS, Perry KME. Like a fish out of water: Reconsidering disaster recovery and the role of place and social capital in community disaster resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(3):395–411. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. “The trauma experienced by generations past having an effect in their descendants”: Narrative and historical trauma among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2013;0(0):1–31. doi: 10.1177/1363461512467161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley TC. Perceptions and congruence of symptoms and communication among second-generation Cambodian youth and parents: A matched-control design. Child psychiatry and human development. 2006;37(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud N, Shankardass K, O’Campo P, Anderson K, Agbaria AK. Internal displacement and health among the Palestinian minority in Israel. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(8):1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daud A, Skoglund E, Rydelius PA. Children in families of torture victims: Transgenerational transmission of parents’ traumatic experiences to their children. International Journal of Social Welfare. 2005;14(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Degloma T. Expanding trauma through space and time: Mapping the rhetorical strategies of trauma carrier groups. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2009;72(2):105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Denham AR. Rethinking historical trauma: Narratives of resilience. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45(3):391–414. doi: 10.1177/1363461508094673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran E. Healing the Soul Wound: Counseling with American Indians and Other Native Peoples. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Duran B. Native American Postcolonial Psychology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JA. Apologizing for the past for a better future: Collective apologies in the United States, Australia, and Canada. Southern Communication Journal. 2010;75(1):57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Elias B, Mignone J, Hall M, Hong SP, Hart L, Sareen J. Trauma and suicide behaviour histories among a Canadian indigenous population: An empirical exploration of the potential role of Canada’s residential school system. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(10):1560–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppel S. Reburial ceremonies for health and healing after state terror in Zimbabwe. The Lancet. 2002;360(9336):869–870. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09960-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(3):316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T, Walters KL, Pearson CR, Campbell CD. Indian Boarding School Experience, Substance Use, and Mental Health among Urban Two-Spirit American Indian/Alaska Natives. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):421–427. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.701358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Habermas T, Waters TE, Zaman W. The making of autobiographical memory: Intersections of culture, narratives and identity. International Journal of Psychology. 2011;46(5):321–345. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.596541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. In: “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976. Macey D, translator; Bertani M, Fontana A, editors. New York, NY: Picador; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fryberg SA, Markus HR, Oyserman D, Stone JM. Of warrior chiefs and Indian princesses: The psychological consequences of American Indian mascots. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2008;30(3):208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove M. Psychiatric implications of displacement: Contributions from the psychology of place. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(15):1516–1523. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove M. Root shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. New York: One World/Ballantine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz M. Public narrative, collective action, and power. In: Odugbemi S, Lee T, editors. Accountability Through Public Opinion: From Inertia to Public Action. Washington, D.C: The World Bank; 2011. pp. 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP. Redressing First Nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for Indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2013;50(5) doi: 10.1177/1363461513487669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Miller PJ, Rappaport J. Conceptual self as normatively oriented: The suitability of past personal narrative for the study of cultural identity. Culture & Psychology. 1999;5(4):371–398. [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2012;8:131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TL, Darity WA., Jr Under the skin: Using theories from biology and the social sciences to explore the mechanisms behind the black-white health gap. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S36–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL. Narrative and the cultural psychology of identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2008;12(3):222–247. doi: 10.1177/1088868308316892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education & Behavior. 2007;34(5):777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honwana AM. Healing for peace: Traditional healers and post-war reconstruction in Southern Mozambique. Peace and Conflict. 1997;3(3):293–305. [Google Scholar]

- James EC. The political economy of ‘trauma’in Haiti in the democratic era of insecurity. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):127–149. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000034407.39471.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer D, Stein DJ, Mbanga I, Zungu-Dirwayi N. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa: relation to psychiatric status and forgiveness among survivors of human rights abuses. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178(4):373–377. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karenian H, Livaditis M, Karenian S, Zafiriadis K, Bochtsou V, Xenitidis K. Collective trauma transmission and traumatic reactions among descendants of Armenian refugees. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2011;57(4):327–337. doi: 10.1177/0020764009354840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann NP. Psychopathology in children of Holocaust survivors: a review of the research literature. Israeli Journal of Psychiatry Related Science. 2001a;38(1):36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann NP. Transmission of Holocaust trauma: An integrative view. Psychiatry. 2001b;64(3):256–267. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.3.256.18464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienzler H. Debating war-trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in an interdisciplinary arena. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(2):218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Brass GM, Tait CL. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples: transformations of identity and community. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry/La Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2000;45(7):607–616. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2011;56(2):84. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Olsen JA, Baker A, Legerski JP, Isakson B, Pašalić A, Arslanagić B. Unpacking trauma exposure risk factors and differential pathways of influence: predicting postwar mental distress in Bosnian adolescents. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1053–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary JD. Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. Oakland, CA: Uptone Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lemstra M, Rogers M, Thompson A, Moraros J, Buckingham R. Risk indicators associated with injection drug use in the Aboriginal population. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2012;24(11):1416–1424. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.650678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D, Wong YLR. Time bound: the timescape of secondary trauma of the surviving teachers of the Wenchuan earthquake. American journal of orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(2):241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masalha N. Remembering the Palestinian Nakba: commemoration, oral history and narratives of memory. Holy Land Studies: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2008;7(2):123–156. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Reynolds J, Lewis M, Patten AH, Bowman PJ. When bad things turn good and good things turn bad: Sequences of redemption and contamination in life narrative and their relation to psychosocial adaptation in midlife adults and in students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(4):474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Meštrović SG. A sociological conceptualization of trauma. Social Science & Medicine. 1985;21(8):835–848. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels C. Child Welfare Series. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota Extension Service, Children, Youth and Family Consortium; 2010. Historical trauma and microaggressions: A framework for culturally-based practice. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BG. Bringing culture in: Community responses to apology, reconciliation, and reparations. American Indian culture and research journal. 2006;30(4):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CR, Tharp RG. Integrating cultural community psychology: Activity settings and the shared meanings of intersubjectivity. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49(1):22–30. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pals JL. Narrative Identity Processing of Difficult Life Experiences: Pathways of Personality Development and Positive Self-Transformation in Adulthood. Journal of personality. 2006;74(4):1079–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pals JL, McAdams DP. The transformed self: A narrative understanding of posttraumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry. 2004:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce ME, Christian WM, Patterson K, Norris K, Moniruzzaman A, Craib KJP, Spittal PM. The Cedar Project: Historical trauma, sexual abuse and HIV risk among young Aboriginal people who use injection and non-injection drugs in two Canadian cities. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(11):2185–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack CE. Burial at Srebrenica: Linking place and trauma. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(4):793–801. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J. Community narratives: Tales of terror and joy. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(1):1–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1005161528817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J, Simkins R. Healing and empowering through community narrative. Prevention in Human Services. 1991;10(1):29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman CK. Narrative Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Scrimin S, Moscardino U, Capello F, Altoè G, Steinberg AM, Pynoos RS. Trauma reminders and PTSD symptoms in children three years after a terrorist attack in Beslan. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(5):694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw W. The Chicago Fire--Fifty Years After. The Outlook. 1921;129:176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Simms EM. Children’s Lived Spaces in the Inner City: Historical and Political Aspects of the Psychology of Place. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2008;36(1):72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York, NY: Picador; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sotero M. A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2006;1(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Seedat S, Kaminer D, Moomal H, Herman A, Sonnega J, Williams DR. The impact of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on psychological distress and forgiveness in South Africa. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2008;43(6):462–468. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0350-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62(4):271. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DM, Usborne E. When I know who “we” are, I can be “me”: The primary role of cultural identity clarity for psychological well-being. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2010;47(1):93–111. doi: 10.1177/1363461510364569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebes JK. Philosophical foundations of mixed methods research: Implications for research practice. In: Jason LA, Glenwick DS, editors. Innovative Methodological Approaches to Community-Based Research: Theory and Application. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tebes JK, Irish JT, Puglisi Vasquez MJ, Perkins DV. Cognitive transformation as a marker of resilience. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39(5):769–788. doi: 10.1081/ja-120034015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Beehler S, Deutsch C, Green LW, Hawe P, McLeroy K, Schulz AJ. Advancing the science of community-level interventions. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1410. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usborne E, Taylor DM. The role of cultural identity clarity for self-concept clarity, self-esteem, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36(7):883–897. doi: 10.1177/0146167210372215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ville I, Khlat M. Meaning and coherence of self and health: An approach based on narratives of life events. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;64(4):1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls ML, Whitbeck LB. Distress among Indigenous North Americans. Society and Mental Health. 2011;1(2):124–136. doi: 10.1177/2156869311414919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Mohammed SA, Evans-Campbell T, Beltrán RE, Chae DH, Duran B. Bodies don’t just tell stories, they tell histories. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2011;8(1):179–189. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X1100018X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska natives: Incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Report. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S104–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertsch JV. The narrative organization of collective memory. Ethos. 2008;36(1):120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler LM, DiFluvio G, Burke TK. Resilience and marginalized youth: Making a case for personal and collective meaning-making as part of resilience research in public health. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(4):565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(3–4):119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Adams GW. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: Culturally specific risk and resiliency factors for alcohol abuse among American Indians. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2004;65(4):409–418. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Walls ML, Johnson KD, Morrisseau AD, McDougall CM. Depressed affect and historical loss among North American Indigenous adolescents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2009;16(3):16–41. doi: 10.5820/aian.1603.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. The Harmony of Illusions: Inventing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Young A. When traumatic memory was a problem: on the historical antecedents of PTSD. In: Rosen G, editor. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Issues and Controversies. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2004. pp. 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas M, Bekerman Z. Education and the dangerous memories of historical trauma: Narratives of pain, narratives of hope. Curriculum Inquiry. 2008;38(2):125–154. [Google Scholar]