Abstract

Objective

This systematic review examines experimental studies that test the effectiveness of strategies intended to integrate empirically supported mental health interventions into routine care settings. Our goal was to characterize the state of the literature and to provide direction for future implementation studies.

Methods

A literature search was conducted using electronic databases and a manual search.

Results

Eleven studies were identified that tested implementation strategies with a randomized (n = 10) or controlled clinical trial design (n = 1). The wide range of clinical interventions, implementation strategies, and outcomes evaluated precluded meta-analysis. However, the majority of studies (n = 7; 64%) found a statistically significant effect in the hypothesized direction for at least one implementation or clinical outcome.

Conclusions

There is a clear need for more rigorous research on the effectiveness of implementation strategies, and we provide several suggestions that could improve this research area.

Keywords: implementation research, implementation strategies, empirically supported interventions, mental health services research, evidence-based treatments

Introduction

Quality Gaps in Mental Health Care

Concerns about the quality of mental health care provided in the United States are well-documented (Institute of Medicine, 2006; President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003), and a number of studies have found that the majority of mental health consumers receive care that is not based upon the best available evidence (e.g., Garland et al., 2010; Kohl, Schurer, & Bellamy, 2009; Raghavan, Inoue, Ettner, & Hamilton, 2010; Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, 2000; Zima et al., 2005). This is partly due to a myriad of barriers at the client, clinician, organizational, system, and policy levels that have been well documented in the literature (Flottorp et al., 2013). This has led key stakeholders involved in the financing, provision, and receipt of mental health services to advocate for the increased use of evidence-based approaches to prevention and treatment (American Psychological Association, 2005; Birkel, Hall, Lane, Cohan, & Miller, 2003; Howard, McMillen, & Pollio, 2003; Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research, 2007; Institute of Medicine, 2006, 2009a; Kazdin, 2008; National Institute of Mental Health, 2008; President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003; Thyer, 2002).

Evidence-Based Practice Models

A commonly endorsed definition of evidence-based practice is “the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences” (American Psychological Association, 2005, p. 5). Two complementary approaches to advancing the use of evidence in practice are the evidence-based practice process model and the direct application of empirically supported interventions (ESIs). The evidence-based practice process requires that practitioners or organizations: 1) form an answerable question; 2) seek the best evidence to answer that question; 3) critically appraising the evidence; 4) integrate that appraisal with their clinical expertise, client values, preferences, and clinical circumstances; and 5) evaluate the outcome (Gibbs, 2003). A helpful example of the application of this process has been published in this journal (McCracken & Marsh, 2008), and a recent review identified a number of studies that evaluated efforts to implement the evidence-based practice process in community settings (Gray, Joy, Plath, & Webb, 2012). The direct application of ESIs, which is the focus of our review, involves integrating interventions that have some evidence for their efficacy and effectiveness for a given population or clinical problem into routine care settings. Specific benchmarks have been proposed for the level of evidence required before an intervention can be deemed “evidence-based” (Chambless et al., 1998; Roth & Fonagy, 2005; Weissman et al., 2006), and in some fields, such as mental health and child welfare, a growing number of ESIs have been catalogued in repositories of programs and practices that rate the quality of evidence supporting their use (Soydan, Mullen, Alexandra, Rehnman, & Li, 2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012; The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare, 2012).

Implementation Research

Implementation research has emerged as one way of addressing the quality gaps in a variety of fields, including mental health (Brownson, Colditz, & Proctor, 2012, McMillen, 2012). Implementation research is defined as, “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices…to improve the quality (effectiveness, reliability, safety, appropriateness, equity, efficiency) of health care” (Eccles et al., 2009, p. 2). It has been prioritized and supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; National Institute of Mental Health, 2008; National Institutes of Health, 2013) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM; Institute of Medicine, 2007, 2009b), both of which have called for more research that focuses on the identification, development, refinement, and testing of implementation strategies.

Implementation Strategies

Implementation strategies can be defined as systematic intervention processes to adopt and integrate evidence-based health innovations into routine care, or the “how” of implementation (Powell et al., 2012). In their review of implementation strategies in the mental health and health literature, Powell et al. (2012) describe distinctions between “discrete” implementation strategies comprised of single actions (e.g., educational workshops or reminders), “multifaceted” strategies that combine two or more discrete actions (e.g., training plus audit and feedback), or more comprehensive “blended” implementation strategies that incorporate multiple strategies packaged as a protocolized or branded implementation intervention. Examples of blended strategies include the Availability, Responsiveness, and Continuity (ARC) intervention (Glisson et al., 2010; Glisson, Dukes, & Green, 2006) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series Collaborative Model (Ebert, Amaya-Jackson, Markiewicz, Kisiel, & Fairbank, 2012; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003). A number of implementation strategies have been described in the literature. For example, the review by Powell et al. (2012) identified 68 discrete strategies that can be used to plan, educate, finance, restructure, manage quality, and attend to the policy context to facilitate implementation.

Several reviews of implementation strategies in mental health have focused on training in ESIs (e.g., Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010). As noted by Powell, McMillen, Hawley, & Proctor (2013), the most consistent finding from this literature is that while passive approaches to implementation (e.g., single session workshops, distribution of treatment manuals) may increase provider knowledge and even predispose providers to adopt a treatment, passive approaches do little to produce provider behavior change (Davis & Davis, 2009). In contrast, effective training approaches often involve multifaceted strategies including: a treatment manual, multiple days of intensive workshop training, expert consultation, live or taped review of client sessions, supervisor trainings, booster sessions, and the completion of one or more training cases (Herschell et al., 2010). Leaders in the area of training have also suggested that training should be dynamic, active, and address a wide range of learning styles (Davis & Davis, 2009); utilize behavioral rehearsal (Beidas, Cross, & Dorsey, 2013); and include ongoing supervision, consultation, and feedback (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010).

Despite this emerging evidence for particular approaches to training, there is a need for more rigorous research that tests a broad range of strategies (i.e., those not just focusing on training) for implementing psychosocial treatments in mental health (Goldner et al., 2011; Herschell et al., 2010). For instance, a scoping review of the published literature focusing on implementation research in mental health identified 22 RCTs, only two of which tested psychosocial interventions in mental health settings (Goldner et al., 2011). This stands in contrast to the broader field of health care, where the number of RCTs testing implementation strategies dwarfs those in mental health and social service settings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) group (“Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group,” n.d.) has conducted systematic reviews that document the effectiveness of implementation strategies such as printed educational materials (12 RCTs, 11 non-randomized studies), educational meetings (81 RCTs), educational outreach (69 RCTs), local opinion leaders (18 RCTs), audit and feedback (118 RCTs), computerized reminders (28 RCTs), and tailored implementation strategies (26 RCTs, Grimshaw, Eccles, Lavis, Hill, & Squires, 2012). This and the dominance of fields such as medicine and nursing in the only journal presently dedicated to implementation research, Implementation Science, has led Landsverk, Brown, Rolls Reutz, Palinkas, & Horwitz (2011) to conclude that the field of mental health has lagged behind other disciplines in building an evidence-base for implementation. Importantly, the lack of reviews providing an in-depth characterization of rigorous implementation research (i.e., those employing experimental manipulation) in mental health or the social services limits the field’s understanding of the implementation strategies used or found to be effective in these settings.

Overview of Implementation Models

In addition to examining the empirical evidence supporting the use of certain implementation strategies, implementation stakeholders may find it helpful to draw upon the wealth of theoretical perspectives that can inform the design, selection, and evaluation of implementation strategies (Grol, Bosch, Hulscher, Eccles, & Wensing, 2007; Michie, Fixsen, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2009; The Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG), 2006). Indeed, as Proctor, Powell, Baumann, Hamilton, & Santens (2012) note, conceptual models can be “…useful in framing a study theoretically and providing a ‘big picture’ of the hypothesized relationships between variables” (p. 6), and specifying key contextual variables that may serve as moderators or mediators of implementation and clinical outcomes. Theories can be helpful in designing and selecting implementation strategies as they can specify the mechanisms by which they may exert their effects (Proctor et al., 2012). We direct readers to two very helpful reviews of implementation models (Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2012) and theories (Grol et al., 2007).

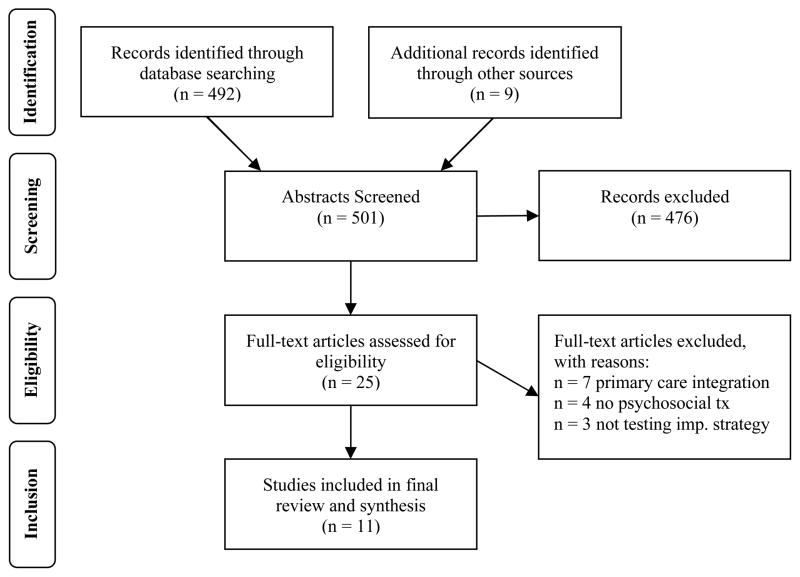

Two conceptual frameworks guide our current review. First, Proctor et al.’s (2009) conceptual model of implementation research (Figure 1) informs the present review by highlighting the fact that implementation efforts require both an ESI and an implementation strategy or set of implementation strategies designed to integrate that ESI into routine care. It also differentiates between implementation outcomes such as acceptability, cost, fidelity, penetration, sustainability (Proctor & Brownson, 2012; Proctor et al., 2011); service outcomes such as efficiency, safety, and timeliness (Institute of Medicine, 2001); and client outcomes such as symptom reduction and improved quality of life. In addition to framing the core elements of implementation research, this conceptual model identifies implementation strategies as the key component that can be manipulated to achieve differential effects on implementation, service system, and clinical outcomes. While the ultimate goal of implementation efforts is improving clinical outcomes, “intermediate outcomes” such as implementation and service system outcomes are also important, particularly in relation to implementation strategies; improving the acceptability of interventions or the efficiency of services even without improving clinical outcomes may be a worthy goal in and of itself. Empirical tests of implementation strategies could potentially focus solely on implementation outcomes, service system outcomes, or clinical outcomes, though some will evaluate combinations of the three. The model also calls for multilevel implementation strategies by explicitly mentioning various levels of the implementation context, including the systems environment, organizational-, group-, supervision-, and individual provider- and consumer-levels.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of implementation research (Proctor et al., 2009)

This review is also informed by the CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009), which provides one of the most comprehensive overviews of the key theories and conceptual models informing implementation research and practice. The CFIR suggests that implementation is influenced by: 1) intervention characteristics (evidentiary support, relative advantage, adaptability, trialability, and complexity), 2) the outer setting (patient needs and resources, organizational connectedness, peer pressure, external policy and incentives), 3) the inner setting (structural characteristics, networks and communications, culture, climate, readiness for implementation), 4) the characteristics of individuals involved (knowledge, self-efficacy, stage of change, identification with organization, etc.), and 5) the process of implementation (planning, engaging, executing, reflecting, evaluating). This model captures the complex, multi-level nature (Shortell, 2004) of implementation, and suggests (implicitly) that successful implementation may necessitate the use of an array of strategies that exert their effects at multiple levels of the implementation context. Indeed, while the CFIR’s utility as a framework to guide empirical research is not fully established, it is consistent with the vast majority of frameworks and conceptual models in dissemination and implementation research in its emphasis of multi-level ecological factors (Tabak et al., 2012). Each mutable aspect of the implementation context that the CFIR highlights is potentially amenable to the application of targeted and tailored implementation strategies (Powell et al., 2012). A “targeted” strategy may be explicitly designed to broadly address one or more levels of the implementation context (e.g., clinician-level knowledge or self-efficacy, organizational culture and climate, financial constraints, etc.), whereas a “tailored” strategy would address one or more levels for a specific treatment, organization, or treatment setting based upon a prospective identification of barriers to change (Bosch, van der Weijden, Wensing, & Grol, 2007). Examining research (and real-world implementation efforts) through the lens of the CFIR gives us some indication of how comprehensively strategies address important aspects of implementation.

Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of this systematic review is to characterize studies that test the effectiveness of implementation strategies in order to consolidate what has been learned about the effectiveness of implementation strategies and (perhaps more importantly) inform future research on the development, refinement, and testing of implementation strategies in mental health service settings. More specifically, this review seeks to answer the following questions: 1) What theories and conceptual models have guided this implementation research?; 2) What types of strategies have been rigorously evaluated and are they discrete, multifaceted, or blended?; 3) To what extent do studies attend to theoretical domains identified as important to the field of implementation science?; 4) What is the range of distal (i.e., clinical) outcomes and intermediate outcomes (i.e., implementation outcomes and service system outcomes) assessed?; and 5) Which strategies are most effective in improving clinical and implementation outcomes?

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review identified empirical research involving the implementation of an ESI or practice guideline in mental health or social service systems. To be included, studies had to involve both an implementation strategy (i.e., an intervention specifically intended to integrate an ESI into routine care) and an evidence-based psychosocial treatment or treatment guideline. We assumed a treatment to be “empirically supported” if the authors cited evidence that supported its efficacy or effectiveness. Following Landsverk et al. (2011), who conducted a structured review of rigorous implementation studies for the purpose of examining elements of the research designs, the search allowed interventions that occurred outside of traditional mental health service settings (e.g., schools) when the intervention was delivered by a professional whose primary focus was on mental health treatment. Our study design criteria required the use of a comparative design to test the implementation strategy that met standards of rigor set forth by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group (2002a). EPOC designates four designs as appropriate for testing the effectiveness of implementation strategies, including: 1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 2) controlled clinical trials (CCTs), 3) controlled before and after studies, and 4) interrupted time series studies. Descriptions of these designs have been described elsewhere (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002a; Landsverk et al., 2011). As specified by EPOC (2002a), controlled clinical trials are similar to RCTs, except that the assignment of participants (or other units) is based upon a quasi-random process of allocation (e.g., alternation, date of birth, patient identifier) rather than a true process of random allocation (e.g., random number generation, coin flips). Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English in peer-reviewed journals. The search was not restricted by date, country, or the type of outcomes evaluated (e.g., implementation, service system, or clinical).

In line with our goal to evaluate strategies for implementing psychosocial mental health ESIs, we excluded studies that focused primarily on physical health, substance abuse, and pharmacological interventions, as well as studies that focused primarily on testing the efficacy or effectiveness of a given clinical intervention. We acknowledge that while pharmacological interventions are often an essential component of mental health treatment, psychosocial interventions can be considered more complex, and thus more difficult to implement than pharmacological interventions (Michie et al., 2009). While we reviewed the full-text articles of several studies of primary care-mental health integration such as the IMPACT trial (e.g., Asarnow et al., 2005; Grypma, Haverkamp, Little, & Unützer, 2006; Ngo et al., 2009; Wells et al., 2000), we ultimately decided to exclude these studies because they generally were aimed at testing the efficacy or effectiveness of new models of clinical care for a given condition, rather than the implementation of a specific ESI.

Search Strategy

In order to target the literature on mental health services, we searched CINAHL Plus, Medline, PubMed, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX on January 4, 2011 using the EBSCO database host. The search strategy (see Table 1) included four concepts: 1) implementation or dissemination, 2) evidence-based practices, 3) mental health service settings, and 4) eligible research designs. The specific terms used in the “implementation/dissemination” concept were selected due to their superiority in accurately identifying knowledge translation (otherwise known as implementation) studies in a recent systematic review (McKibbon et al., 2010). The methodological search terms were identified through the Cochrane review group as mentioned above. Additionally, hand searches of the reference lists of implementation strategy reviews (e.g., Jamtvedt, Young, Kristoffersen, O’Brien, & Oxman, 2006; Landsverk et al., 2011) were conducted to identify relevant articles.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Search string: |

|---|

|

Data Extraction and Coding Procedures

At least two reviewers independently reviewed and extracted data from each article. Two data collection tools aided the extraction process. First, a modified version of the Cochrane EPOC Data Abstraction Form (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002b) was used to extract information about the clinical interventions, strategies, outcomes, and results. We created a checklist, guided by the conceptual model of Proctor and colleagues (2009), for extraction of implementation, service system, and clinical outcomes. We also documented psychometric properties of outcome measures if they were reported in the articles.

We also made use of a checklist (see Table 3) that included the domains and subdomains of the CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009). This allowed a meaningful classification of implementation strategies according to conceptual “targets” that they addressed. Multiple targets for each strategy were allowed when applicable. For example, educational workshops, which generally focus on the attitudes and knowledge of individuals, were classified under “characteristics of individuals” (broad domain) and “knowledge and beliefs about intervention” (subdomain); if the authors further specified that the workshop targeted self-efficacy or individuals’ stage of change, we also marked the respective categories. This classification system affords the opportunity to approximate the level of comprehensiveness of the strategies evaluated in each study (i.e., strategies are more comprehensive if they target more conceptual domains). This approach was previously used to enrich the understanding of implementation strategies applied to alcohol screening and brief intervention (Williams et al., 2011).

Table 3.

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) domains and subdomains targeted by strategies in each study

| Atkins et al., 2008 | Azocar et al., 2003 | Bert et al., 2008 | Chamberlain et al., 2008 | Forsner et al., 2010 | Glisson et al., 2010 | Herschell et al., 2009 | Kauth et al., 2010 | Kramer et al., 2008 | Lochman et al., 2009 | Weisz et al., 2012 | % of studies addressing domain: | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Intervention Characteristics assessed? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 45% |

| A. Intervention Source | 0% | |||||||||||

| B. Evidence Strength and Quality | X | X | 18% | |||||||||

| C. Relative Advantage | 0% | |||||||||||

| D. Adaptability | X | X | X | X | 36% | |||||||

| E. Trial ability | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| F. Complexity | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| G. Design quality and packaging | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| H. Cost | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| Subtotal for Intervention Characteristics | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| II. Outer Setting assessed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 55% |

| A. Patient Needs and Resources | X | X | X | X | 36% | |||||||

| B. Cosmopolitanism | X | X | 16% | |||||||||

| C. Peer Pressure | 0% | |||||||||||

| D. External Policies and Incentives | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| Subtotal for Outer Setting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| III. Inner Setting assessed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 82% |

| A. Structural Characteristics | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| B. Networks and Communication | X | X | X | 27% | ||||||||

| C. Culture | X | X | 18% | |||||||||

| D. Implementation Climate | X | X | X | X | X | 45% | ||||||

| 1. Tension for Change | X | X | 18% | |||||||||

| 2. Compatibility | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| 3. Relative Priority | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| 4. Organizational incentives and rewards | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| 5. Goals and feedback | X | X | X | X | X | 45% | ||||||

| 6. Learning climate | X | X | 18% | |||||||||

| E. Readiness for implementation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 81% | ||

| 1. Leadership engagement | X | X | X | X | 36% | |||||||

| 2. Available resources | 0% | |||||||||||

| 3. Access to knowledge and information | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 64% | ||||

| Subtotal/count for Inner Setting | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | |

| IV. Characteristics of Individuals assessed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| A. Knowledge and beliefs about intervention | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 100% |

| B. Self-efficacy | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| C. Individual stage of change | X | 9% | ||||||||||

| D. Individual identification with organization | 0% | |||||||||||

| E. Other personal attributes | X | X | X | X | 36% | |||||||

| Subtotal/count for Characteristics of Individuals | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| V. Process of implementation assessed? | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 64% |

| A. Planning | X | X | X | X | X | 45% | ||||||

| B. Engaging | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 55% | ||||

| 1. Opinion leaders | X | X | 18% | |||||||||

| 2. Internal implementation leaders* | X | X | 18% | |||||||||

| 3. Champions | 0% | |||||||||||

| 4. External change agents | X | X | X | X | X | X | 55% | |||||

| C. Executing | X | X | X | X | 36% | |||||||

| D. Reflecting and evaluating | X | X | X | X | 36% | |||||||

| Subtotal/count for Process of Implementation | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| Total CFIR domains addressed (CFIR subdomains in parentheses) | 5(14) | 3(4) | 4(6) | 4(7) | 3(17) | 4(20) | 2(4) | 3(12) | 4(12) | 2(4) | 4(7) |

Note: A “Yes” or “No in the rows labeled with a CFIR domain indicates whether any component of the domain was targeted with an implementation strategy. An X in the CFIR subdomain row is marked when the general subdomain was targeted by an implementation strategy. For rows labeled by a specific component of a CFIR subdomain, an X indicates the component was targeted by an implementation strategy.

Though we did not calculate inter-rater reliability statistics (i.e., Cohen’s kappa), we found it difficult to achieve high reliability during the first round of coding, particularly when coding the theoretical domains outlined by Damschroder and colleagues (2009). This is partly due to wide variations in the quality of reporting and the justification for the use of implementation strategies in the included studies, a point that we consider further in the discussion section. These challenges compelled us to hold a number of face-to-face meetings in which coding discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus.

Methods of Synthesis

The wide range of clinical interventions, implementation strategies, and outcomes evaluated in the included studies (see below) precluded meta-analysis. We primarily relied upon tabulation, textual descriptions, and vote-counting to summarize the included studies and answer the primary research questions of this review (Popay et al., 2006). The first four research questions addressed in this review were appropriately addressed through tabulation (see Tables 2 and 3) and textual descriptions in the results and discussion sections. We also used vote-counting to calculate the number of studies that achieved statistically significant results on primary outcomes, as well as the number of studies that addressed the conceptual domains outlined by Damschroder and colleagues (2009). There are limitations to using vote counting to determine the effectiveness of interventions, as it gives equal weight to studies of varying sample sizes, effect sizes, and significance levels (Popay et al., 2006); thus, we temper our interpretation of results accordingly.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies

| Study | Setting, design, and level at which randomization occurred (LOR) | Participants | Guiding theories/ models specified | Clinical Intervention | Classification and Description of Implementation Strategies | Outcomes Assessed: Implementation (IOs), service system (SSOs), or clinical outcomes 50 (COs) | Summary of Outcome Attainment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atkins et al. (2008) |

Setting: Urban elementary schools Design: RCT LOR: School |

Opinion leader teachers (N=12), mental health providers (N=21), and teachers (N=105) in ten urban schools (6 treatment, 4 control) | Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations | ADHD Best Practices (Mental Health and Educational) |

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

The adoption of ADHD management practices for both groups declined over time, only to increase slightly by the end of the study. The authors note mixed effects regression models show that opinion leaders in collaboration with mental health providers promoted higher adoption of best practices for ADHD management, and that these effects were mediated by opinion leader support. |

| Azocar, Cuffel, Goldman, & McCarter (2003) |

Setting: Community-based, multi-disciplinary group of clinicians associated with a managed behavioral health care organization Design: RCT LOR: Individual clinician |

Mental health clinicians (N=443) | Not discussed | Practice guidelines for depression |

Discrete

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

Non-significant findings across all outcomes, except that clinicians’ subjective ratings of guideline adherence was actually lower for the targeted mailing group as compared to the mass mailing or control group. |

| Bert, Farris, & Borkowski (2008) |

Setting: Community settings (web-based and booklet-only condition) and university lab (face-to-face training condition) Design: RCT LOR: Individual parent |

Mothers (N=134) | Not discussed | Adventures in Parenting (training program that teaches parenting intervention principles) |

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

Both face-to-face and web-based trainings were associated with significant increases in knowledge as compared to the booklet only condition. Significant differences were not found between the face-to-face and web-based trainings. |

| Chamberlain, Price, Reid, & Landsverk (2008) |

Setting: Community organizations in San Diego County Design: RCT LOR: Individual foster care giver |

Foster caregivers and children (N=700) | Not discussed but Rogers Diffusion of Innovation Theory is cited | Multi-dimensional Treatment Foster Care |

Multifaceted

Note: Both conditions also benefited from supervision, consultation, the engagement of community stakeholders using both top-down and bottom-up approaches, community-based participatory research, and focus groups. |

IOs: Not assessed SSOs: Not assessedCOs:

|

This study demonstrated that train-the-trainer methods achieved statistically similar outcomes (child behavior problems), which suggests that the cheaper and wider reaching method of training (cascading train-the-trainer) is a promising approach |

| Forsner et al. (2010) |

Setting: Psychiatric clinics in Stockholm, Sweden Design: RCT LOR: Clinic |

Patients in 6 psychiatric clinics (N=2,165) | Cyclical model of change (PDSA cycles) and organizational learning theory | Clinical Guidelines for Depression and Suicidal Behaviors |

Multifaceted

|

IOs: Compliance to the clinical guidelines based upon process indicators SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

Compliance to guidelines improved from baseline and was maintained at 12 and 24 months in the active implementation group, whereas there was no change or a decline in compliance in the control group. |

| Glisson et al. (2010) |

Setting: Community organizations in rural Appalachian counties in Tennessee Design: RCT (2×2 factorial design) LOR: County and individual youth |

Children (N=615) and caregivers in 14 counties served by 35 therapists | Not discussed (though other ARC articles discuss theoretical basis in great detail) | Multi-systemic Therapy (MST) |

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs:

COs:

|

MST therapists in the ARC condition were more efficient, spending less time with the youth’s family system. MST therapists in the ARC condition were equally likely to address multiple subsystems, though MST/ARC therapists were more likely to demonstrate progress in 9 of the 16 subsystems. There were no differences between ARC and non-ARC conditions regarding therapist adherence/fidelity. Finally, problem behavior in the MST plus ARC condition was at a nonclinical level and significantly lower than other conditions, and youth entered out-of-home placements at a significantly lower rate (16%) than in the control condition (34%). |

| Herschell et al. (2009) |

Setting: Community-based mental health centers in California Design: CCT LOR: N/A |

Mental health clinicians (N=42) from 11 mental health centers | Not discussed | Parent-Child Interaction Therapy | Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

Reading the treatment manual alone increased knowledge, but not skill. Both the didactic and experimental training groups increased knowledge, skill, and satisfaction, though there were no significant differences between those conditions. Few demonstrated mastery of skills. |

| Kauth et al. (2010) |

Setting: VA clinics Design: RCT LOR: Clinic |

Mental health clinicians (N=23) in 20 VA clinics | Fixsen et al.’s “implementation drivers” and the PARiHS Model | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) |

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

No statistically significant difference when comparing mean change in self-reported CBT use, though the trend for the facilitation group was clearly in the hypothesized direction, increasing by 18.7 percentage points (or 27.7 additional hours of CBT per month). The total cost for facilitator’s and 12 therapists time spent in facilitation was $2,458.80 over seven months for a benefit of about 28 additional hours of CBT per month per therapist. |

| Kramer & Burns (2008) |

Setting: Two urban mental health centers Design: RCT LOR: Clinician |

Mental health clinicians (N=17) | Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation and the authors cite a number of other theories and models | Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) |

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs: Not assessed |

The majority of clinicians (62%) reported that they understood the basics of CBT; 87% were aware of potential implementation barriers; 95% felt they possessed a set of skills to address barriers; only 50% felt prepared to implement CBT on a regular basis. In terms of CBT use: Three charts indicated no provision of CBT; three indicated adherence to CBT in 1–3 sessions; two indicated CVT in 4–6 sessions, and 8 indicated CBT in more than 6 sessions. |

| Lochman et al. (2009) |

Setting: Public elementary schools in Alabama Design: RCT LOR: Individual school counselor |

School counselors (N=49) and students (N=531) | Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations and “other models of dissemination” | Coping Power |

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs:

|

CP-TF children maintained their levels of externalizing behavior problems and reported lower rates of assaultive behavior while children in the control condition reported increases in both of these outcomes. CP-TF produced significant improvements in children’s expectations regarding the negative consequences of aggression, whereas the control group reported increases in maladaptive assumptions. CP-BT was not as successful in producing change. CP-TF counselors had relatively lower levels of teacher-rated and parent-rated externalizing problems, lower rate of child-reported assaultive behaviors, and reductions in aggressive behavior expectations. However, counselors in the CP-TF and CP-BT conditions did not differ on the implementation outcomes assessed, though CP-TF counselors were significantly more engaged with children. |

| Weisz et al. (2012) |

Setting: Ten outpatient clinical service organizations in Massachusetts and Hawaii Design: RCT LOR: Individual clinician |

Mental health clinicians (N=84) and youth (N=174) | Not discussed |

|

Multifaceted

|

IOs:

SSOs: Not assessed COs:

|

Youths in modular treatment improved faster than youths in usual care and in standard (ESI) treatment. There were no differences between the standard condition and usual care. Additionally, youths in modular condition showed significantly fewer post-treatment diagnoses. Again, there were no differences between the standard condition and usual care. |

Note. The numbers in the “clinical intervention” and “classification and description of implementation strategies” column refer to different treatment and/or implementation conditions. ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ARC = Availability, Responsiveness, and Continuity intervention; BASC = Behavior Assessment System for Children; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; CCT = controlled clinical trial; CDI = child directed interactions; CO = clinical outcome; CP-BT = Coping Power-basic training; CP-TF = Coping Power-training plus feedback; DPICS = Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System; ESI = empirically supported intervention; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; IO = implementation outcome; LOR = level of randomization; MST = Multisystemic Therapy; OLCPS = Objectives List for Coping Power Sessions; PDSA = plan, do, study, act; PARiHS = Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RPM3 = responding, preventing, monitoring, mentoring, and modeling; SAM = Supervisor Adherence Measure; SSO = service system outcome; TAM-R = Therapist Adherence Measure-Revised; VA = U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Results

Search Results

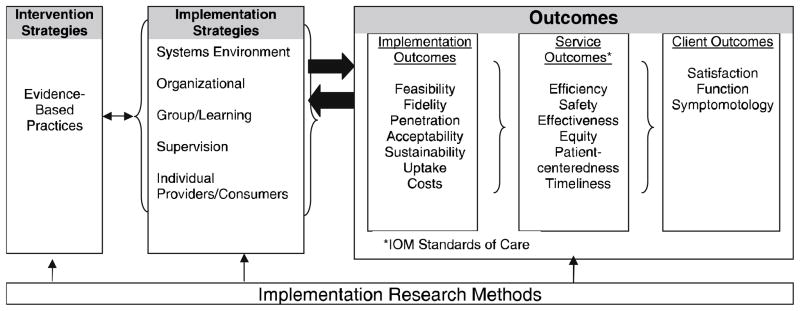

The results of the database and hand search process are displayed in the flowchart in Figure 2. A total of 501 abstracts were identified through the database (n = 492) and hand search (n = 9) process. Abstracts were screened for eligibility and 25 full-text articles were identified as potentially relevant. Ultimately, 11 articles met inclusion criteria, each of which is denoted with an asterisk in the reference section. One of the studies described in the Palinkas et al. (2008) article did not have final data published at the time of this search; however, the results have subsequently been published and the more recent article (Weisz et al., 2012) was examined in this review. Table 2 provides an overview of the included studies, including information about each study’s setting(s), design, level of randomization (if applicable), participants, guiding theories/model(s), clinical intervention(s) implemented, implementation strategies evaluated, outcomes assessed (including implementation, service system, and clinical outcomes), and results/outcome attainment.

Figure 2.

Schematic of search and exclusion process

Populations and Treatment Settings in Included Studies

Eight of the eleven included studies were conducted in child and adolescent mental health, with the remaining three focusing on adult mental health. The child and adolescent mental health studies were conducted in diverse service settings, including: schools, daycare centers, foster care and child welfare settings, and community mental health agencies. The adult mental health service settings included: outpatient mental health (through a managed behavioral health care organization), Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, and psychiatric clinics (in Stockholm, Sweden)

Study Designs

The majority of the studies (n = 10; 91%) were RCTs, and one study was a CCT. However, the studies varied dramatically in terms of size, scope, and complexity. For example, Glisson et al. (2010) and Chamberlain, Price, Reid, & Landsverk (2008) both conducted large-scale RCTs involving over 600 youth, whereas Kauth and colleagues (2010) and Kramer and Burns (2008) conducted small randomized studies (n = 23 and n = 17 respectively) that could be characterized as feasibility or pilot studies.

Guiding Theories and Conceptual Models

Five studies (45%) explicitly referenced and/or discussed a guiding theory or conceptual model. Rogers’ (2003) Diffusion of Innovation theory was the most commonly mentioned, as it was discussed and/or cited in four articles. Other well-known models such as the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework (Rycroft-Malone, 2004), Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace’s (2005) implementation drivers, and cyclical models of change such as those utilizing Plan, Do, Study, Act cycles (Berwick, 1996) were also cited, though no other theory aside from Diffusion of Innovations theory was discussed more than once. Four of the studies used theory to inform the selection of the implementation strategies (Atkins et al., 2008; Forsner et al., 2010; Kauth et al., 2010; Lochman et al., 2009). For example, Atkins and colleagues (2008) supported the use of opinion leaders as an implementation strategy by stating, “diffusion theory posits that novel interventions are initiated by a relatively small group of key opinion leaders (KOLs) who serve as influential models for others in their social network” (p. 905). Kramer and Burns (2008) draw upon the characteristics of innovations that may make them easier to implement as they justify their selection of cognitive behavioral therapy by noting its relative advantage (it has been demonstrated to be effective in community trials), trialability (standardized components and manuals have been developed and can aid the implementation process), and compatibility (CBT is introduced in most graduate curricula; thus, it may be familiar and compatible with many clinicians’ training and theoretical orientations).

Types of Strategies Evaluated

The descriptions of the implementation strategies tested in each study are included in Table 2. Azocar, Cuffel, Goldman, & McCarter (2003) conducted the only evaluation of a discrete strategy (disseminating guidelines), while the remaining studies (n =10; 91%) evaluated multifaceted implementation strategies (i.e., combinations of multiple implementation strategies). Nine of those multifaceted strategies included training as an implementation strategy. For example, Lochman et al. (2009) evaluated the effectiveness of training (both initial and ongoing), technical assistance, and audit and feedback in improving implementation and clinical outcomes. Only one study by Glisson and colleagues (2010) evaluated a blended implementation strategy (ARC) that has been manualized. Though their implementation approaches would not technically be classified as blended owing to a lack of manualization, we note that several studies evaluated multifaceted, multi-level implementation strategies by targeting multiple domains of the implementation context.

Implementation Research Conceptual Domains

Table 3 details the conceptual domains and subdomains of the CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009) that were explicitly targeted by implementation strategies in each study. One hundred percent (n = 11) of studies targeted characteristics of individuals, 82% (n = 9) targeted the inner setting, 64% (n = 7) targeted the process of implementation, 55% (n = 6) targeted the outer setting, and 45% (n = 5) of studies employed strategies that targeted intervention characteristics. With regard to characteristics of individuals, we note that all eleven studies fell into this domain owing to their attempt to enhance the knowledge of practitioners, while just four studies targeted characteristics of individuals other than knowledge such as self-efficacy, competence (skill acquisition), individual stage of change, or attitudes such as flexibility, openness, and engagement. The mean number of domains addressed was 3.45 (range = 2–5), and the mean number of sub-domains addressed was 9.73 (range = 4–20).

Implementation, Service System, and Clinical Outcomes Evaluated

Ninety-one percent of studies (n = 10) evaluated at least one implementation or service system outcome, 9% (n = 1) evaluated only clinical outcomes, and 36% (n = 4) of studies evaluated clinical outcomes in addition to implementation or service system outcomes (see Table 2). Examples of implementation and service system outcomes evaluated in these studies were “adoption” of the ESI, “knowledge acquisition” in regards to intervention delivery, “fidelity” to intervention guidelines, “efficiency” in the service system, “increased skill” in delivering the intervention, and “penetration” of intervention delivery throughout providers in the agency. These 11 studies addressed 12 different implementation or service system outcomes. The most frequently addressed implementation outcomes were fidelity (also referred to as adherence or compliance) and provider attitudes toward or satisfaction with the ESI. Only one study evaluated the costs of the implementation strategies. Kauth et al. (2010) assessed the costs and benefits of external facilitation in increasing the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). The external facilitation strategy resulted in a total cost (facilitator’s and therapists’ time) of $2,458.80 for a benefit of approximately 28 additional hours of CBT per month per therapist. Client outcomes included symptom/behavioral checklists and out-of-home placements. The mean number of implementation or service system outcomes assessed was 2.09 (SD = 1.30) and the mean number of client outcomes assessed was .82 (SD = 1.33). This reflects high variability across studies in outcome focus.

Effectiveness of Implementation Strategies

Brief summaries of study outcomes can be found in Table 2. Our ability to make inferences about the effectiveness of implementation strategies was limited due to the wide range of clinical interventions, implementation strategies, and outcomes evaluated. The majority of studies (n = 7; 64%) found a statistically significant effect in the hypothesized direction for at least one implementation or clinical outcome, and all of the studies with the exception of Azocar et al. (2003) provided at least some support for the implementation strategies used (i.e., there was a non-significant change in the hypothesized direction). The results from several studies indicated that passive strategies such as the dissemination of clinical guidelines (Azocar et al., 2003) and treatment manuals (Bert, Farris, & Borkowski, 2008; Herschell et al., 2009) or the use of opinion leaders (Atkins et al., 2008) were ineffective in isolation. There was no clear relationship between the number of theoretical domains and subdomains addressed and the effectiveness of the implementation strategies. Some studies testing very comprehensive implementation strategies demonstrated positive effects (e.g., Forsner et al., 2010; Glisson et al., 2010); however, other studies also demonstrated positive effects with less comprehensive strategies (e.g., Herschell et al., 2009; Lochman et al., 2009).

Discussion and Applications to Social Work

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that assesses the effectiveness of implementation strategies within diverse settings where mental health treatments are delivered (e.g., community mental health centers, schools, daycare centers, foster care, etc.), and that links implementation strategies to conceptual targets deemed important in the implementation literature. The review provides insight into the current state of implementation research within mental health, and presents exemplars of implementation research as well as many areas in which the conceptualization, conduct, and reporting of implementation research can be improved. A major purpose of a literature review is to foster sharper and more insightful research questions (Yin, 2009); thus, we focus our discussion to encourage improvements in implementation research.

Our first interest was to examine the extent to which theories and conceptual models guided comparative tests of implementation strategies. We found that less that 50 percent of studies used theory or conceptual models to explicitly guide the research. Although this is certainly less than optimal, other systematic reviews of implementation strategies in health have found that theory is used even less frequently (Colquhoun et al., 2013; Davies, Walker, & Grimshaw, 2010). In the current review, studies that employed theory did so in order to justify the selection of either a clinical intervention or the implementation strategy selected. In these cases, theories and models were helpful in promoting an understanding of how and why specific strategies were thought to work, which is essential to developing a generalizable body of knowledge that can inform implementation efforts. We do acknowledge that our systematic review was focused on the discussion of theory within the published trial, yet it is possible that the theoretical foundation of the implementation intervention was discussed elsewhere. For instance, though theory was not discussed in the Glisson et al. (2010) article, the theoretical foundations of the ARC intervention have discussed elsewhere in the literature (Glisson et al., 2006; Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005). Nevertheless, it is clear that there is room for improvement when it comes to using and/or reporting theories and conceptual models in implementation research publications.

The types of implementation strategies evaluated using rigorous designs were mostly multifaceted, which is an encouraging finding given the robust body of literature in both health and mental health suggesting that implementation strategies that focus on relatively passive single discrete approaches such as educational workshops - or “train and hope” approaches (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Liao, Letourneau, & Edwards, 2002) - are not effective in changing provider behavior (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Davis & Davis, 2009; Herschell et al., 2010). Incorporating a variety of strategies, such as ongoing training (e.g. “booster sessions”), access to supervision, expert consultation, peer support, and ongoing fidelity monitoring seems to be an important step in ensuring successful implementation and intervention sustainability (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Davis & Davis, 2009; Herschell et al., 2010).

While the frequent use of multifaceted implementation strategies was encouraging, the process of linking the strategies in each study to potential conceptual “targets” in the CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009) revealed significant gaps in targeting the implementation context, which we identify as opportunities for further implementation research. Most studies addressed “characteristics of individuals” by attempting to increase knowledge, yet it is evident that other individual-level aspects essential for implementation such as boosting providers’ self-efficacy and motivation were not addressed. For example, no studies addressed individuals’ identification within the organization, which is important because it may affect their willingness to fully participate and commit to implementation efforts (Damschroder et al., 2009). In addition, just one study addressed self-efficacy of individuals within the organization, which is an important component of behavior change (Cane, O’Connor, & Michie, 2012; Michie et al., 2005). For more examples of individual level factors that may be important to address during implementation, we direct readers to the Theoretical Domains Framework (Cane, O’Connor, & Michie, 2012; Michie et al., 2005).

Our finding that few studies used implementation strategies that targeted intervention characteristics suggests that most existing implementation research in this area to date has neglected certain intervention-related factors, such as their “packaging,” which may improve the potential for implementation success. For reviews of intervention characteristics that may facilitate or impede implementation and sustainability, we direct readers to Grol et al. (2007) and Scheirer (2013). However, the Weisz et al. (2012) study demonstrated the potentially powerful effect of designing interventions that allow for flexibility and adaptation depending upon client needs. Other approaches that have been described in the literature such as the “common elements” and transdiagnostic approaches to treatment may be similarly effective. The common elements approach is predicated on the idea that ESIs for a given disorder (e.g., childhood anxiety disorders) share many common features that contribute to their effectiveness. These common elements can be systematically identified, taught to clinicians, and applied flexibly to meet clients’ needs, relieving clinicians of the burden of learning a whole host of ESI protocols (Barth et al., 2012; Chorpita, Becker, & Daleiden, 2007). Transdiagnostic treatments provide unified treatment protocols for clinical disorders that have overlapping clinical features, high levels of co-occurrence, or common maintaining mechanisms (McHugh, Murray, & Barlow, 2009). Both of these approaches attempt to simplify the provision of evidence-based care by manipulating characteristics of the intervention to make them more widely applicable to the types of clients that clinicians are likely to serve in routine care, and may represent promising opportunities for implementation research.

The outer setting of the implementation context was addressed in few of the reviewed studies. Studies of large-scale implementation efforts have identified the importance of policy level implementation strategies (e.g., aligning financial incentives, altering certification and licensing standards, state partnerships with academic institutions to develop ESI training curriculum for students), and have suggested that different ESIs may even require different policy-level interventions (Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006). Raghavan, Bright, & Shadoin (2008) have highlighted a number of potential change levers at the level of the “policy ecology;” however, few if any of these strategies have been tested empirically. This includes the absence of research evaluating the use of economic incentives intended to improve the quality of mental health services (Ettner & Schoenbaum, 2006).

The inner setting of the implementation context was addressed frequently (n = 9; 82%) by providing access to new information. Far fewer studies explicitly attempted to influence structural characteristics, organizational culture (Glisson et al., 2010 is one exception), implementation climate, or organizational leadership. While some structural characteristics that impact implementation (for a meta-analysis of determinants and moderators of organizational innovation, see Damanpour, 1991) may not be readily changed (e.g., organizational size), strategies that focus on networks and communication, organizational culture and climate, and implementation climate are needed. Efforts to conceptualize and measure implementation climate and implementation leadership are emerging (Aarons, Horowitz, Dlugosz, & Ehrhart, 2012; Weiner, Belden, Bergmire, & Johnston, 2011), and these measures and frameworks can serve a very practical purpose by guiding the targeted application of implementation strategies to increase the likelihood of implementation success (Aarons et al., 2012).

Finally, there may also be opportunities to address the “process” of implementation to develop implementation programs that are more flexible and adaptive to the needs of the implementation context. Even some of the earliest implementation studies (e.g., Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984) have recognized the unpredictable nature of implementation processes that necessitates iterative (rather than linear) approaches. Thus, there may be room for implementation programs that integrate protocolized adaptations, much in the same way that modular treatments (Weisz et al., 2012) allow clinicians to shift treatment protocols to meet client need. Decision aids could be developed that would help stakeholders to select and apply techniques from a menu of implementation strategies that may address specific and ever-changing contextual demands. Of course, this will require a more robust evidence-base for specific implementation strategies as well as a more nuanced understanding of contextual determinants of change.

The included studies evaluated a range of clinical and implementation outcomes. As Proctor and colleagues (2011) note, the wide variation in outcomes assessed and the inconsistent use of terminology to describe implementation outcomes reflects a lack of consensus in implementation science about how to assess successful implementation. The implementation outcomes addressed most frequently included fidelity, attitudes toward or satisfaction with the ESI, and adoption. Several implementation outcomes identified in a recently published review (Proctor et al., 2011) were underutilized or absent, including: appropriateness of the intervention to the target population, implementation costs, the feasibility of the intervention within the setting, and the sustainability of the intervention after implementation. Some studies evaluated constructs like intervention acceptability or client satisfaction with services in relation to the evidence-based treatments being implemented, but did not assess the acceptability of the implementation strategies that were tested. Implementation outcomes such as acceptability, appropriateness, cost, and feasibility may all have direct bearing on whether a strategy or set of strategies will be effective in the “real world.” Unfortunately, cost was assessed in only one of the eleven studies, which severely limits the usefulness of this research to policy makers and organizational leaders who are charged with making decisions about which implementation strategies to adopt (Grimshaw et al., 2006; Raghavan, 2012; Vale, Thomas, MacLennan, & Grimshaw, 2007). Future studies should take care to integrate a wider range of implementation outcomes whenever possible, as they can serve as indicators of implementation success, proximal indicators of implementation processes, and key intermediate outcomes in relation to service system or clinical outcomes (Proctor et al., 2011). Efforts are underway to catalog and rate the quality of implementation related measures (Rabin et al., 2012) to promote the use of a wider array of valid and reliable instruments and serve to catalyze the development of new measures needed to advance the field.

A promising finding of this review was that approximately two-thirds (64%) of studies demonstrated beneficial effects of employing implementation strategies to improve intermediate and/or clinical outcomes over the comparison conditions. The results from several studies seem to suggest that passive strategies (e.g., disseminating guidelines or manuals, opinion leaders) may represent promising approaches to implementation when combined with other strategies; however, in isolation, they may lack the intensity and comprehensiveness that successful implementation requires.

The diverse range of clinical interventions, implementation strategies, comparison conditions, and outcomes precluded our ability to aggregate evidence regarding the effectiveness of specific implementation strategies using meta-analytic techniques. Another challenge we faced was interpreting the results of studies that evaluated multifaceted strategies. As Alexander and Hearld (2012) note, it is “difficult to parse out the effects of individual intervention components and determine whether some components are more important than others” (p. 4). The relative dearth of theoretical justification for the selection and testing of specific discrete strategies exacerbated this problem by precluding our ability to understand how strategies were thought to improve implementation, service system, and/or clinical outcomes. Alexander and Hearld (2012) recommend addressing this problem by complementing traditional quantitative methods with qualitative methods that allow for the exploration of dynamic, multifaceted aspects of multifaceted interventions. Other scholars have also called for mixed methods approaches to implementation and mental health services research (in part) for this very reason (Palinkas, Horwitz, Chamberlain, Hurlburt, & Landsverk, 2011; Palinkas, Aarons, et al., 2011; Powell, Proctor, et al., 2013).

In an effort to make meaningful comparisons between studies that had different design characteristics we linked the implementation strategies in the included studies to a conceptual framework of implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009). Doing so allowed us to explore implementation effectiveness at the level of the implementation context, which indirectly provided insight into debates regarding the effectiveness of multifaceted implementation strategies versus discrete strategies. Grimshaw et al.’s (2006) extensive review of guideline implementation strategies in health concluded that there was no evidence that multifaceted strategies were superior to single-component strategies. Others have suggested that the reason for Grimshaw and colleagues’ (2006) finding is that many multifaceted strategies focus on only one level of the implementation context (Wensing, Bosch, & Grol, 2009). For instance, the combination of educational workshops, supervision, and consultation would be considered multifaceted, but each of those strategies focuses primarily on the individual-level. In the present study, we found no difference in outcome attainment (clinical or implementation) between studies that targeted multiple theoretical domains or subdomains of the CFIR and studies that targeted fewer domains or subdomains, providing evidence that is consistent with Grimshaw and colleagues (2006). It is possible that factors such as the intensity or dosage of implementation strategies could sometimes be more important to implementation effectiveness than the comprehensiveness of the implementation effort. It is also possible that counting the number of CFIR domains addressed is a limited proxy for the intensity and comprehensives of the strategies. For example, some studies (e.g., Atkins et al., 2008) addressed many CFIR domains and subdomains, but used implementation strategies that have been classified as passive (e.g., opinion leaders and educational meetings), whereas other studies (e.g., Lochman et al., 2009) addressed few domains but used implementation strategies that are considered relatively intensive (initial training, monthly ongoing training, individualized problem solving and technical assistance, and audit and feedback of implementation integrity). Future implementation research designs should consider both the diversity of theoretical targets (e.g. CFIR subdomains) and the intensity of the implementation strategies themselves.

Although we did not formally evaluate the methodological quality of included studies, the need for reporting guidelines in implementation research were readily apparent. For instance, while most studies effectively differentiated between clinical interventions and implementation strategies, the description and reporting of implementation strategies could be vastly improved. Forsner et al. (2010) is one excellent example of a study that clearly describes the implementation strategies (even providing a separate box detailing the different strategies employed). In many other cases it was difficult to determine the scope and detail of the implementation strategies used, which obviously limits one’s ability to understand the implementation approach, let alone replicate it. As noted above, it was also difficult to identify the theoretical and conceptual basis for the selection of specific implementation strategies in many studies.

The journal Implementation Science and several others have embraced the WIDER Recommendations (Michie et al., 2009; Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research, 2008) in order to improve the descriptions of implementation strategies, clinical interventions, and the underlying theories that support them. These guidelines may be very helpful to researchers studying implementation strategies in mental health, as they implore researchers to: 1) provide detailed descriptions of interventions (and implementation strategies) in published papers, 2) clarify assumed change processes and design principles, 3) provide access to manuals and protocols that provide information about the clinical interventions or implementation strategies, and 4) give detailed descriptions of active control conditions. A recently developed checklist based upon the WIDER Recommendations may further assist implementation researchers in reporting their studies (Albrecht, Archibald, Arseneau, & Scott, 2013). Despite the utility of the WIDER Recommendations and other reporting guidelines, we also affirm Eccles et al. (2009) call for a suite of reporting guidelines for different types of implementation research. Perhaps, in order to ensure quality contributions by the field of social work to implementation science, social work journals should consider adopting similar reporting strategies.

Several limitations need to be considered. First, the relatively small number of studies and the diverse range of clinical interventions, implementation strategies, and outcomes evaluated made it difficult to come to firm conclusions regarding the effectiveness of specific implementation strategies. We chose to use a “vote counting” approach to synthesis. This approach is prone to the limitations discussed above in the “methods of synthesis” section, but can be a useful way of providing an initial description of the patterns found across studies (Popay et al., 2006) and, coupled with the narrative approach to synthesis that we have utilized, is a useful way of summarizing included studies. Second, we did not include “grey literature;” thus, we may have missed unpublished studies meeting our other inclusion criteria. Third, we did not assess risk of bias/study quality of the included studies, though we do highlight a number of concerns related to the design, conduct, and reporting of implementation research that can inform social work and implementation researchers endeavoring to contribute to this body of knowledge. Future studies should assess study quality/risk of bias, and (if possible) could also assess the level of fidelity to the implementation strategies being tested. Fourth, as Williams et al. (2011) have mentioned, reporting bias may have lead to an underestimation of the domains and subdomains of the CFIR that were addressed in each study – that is, the authors may not have reported key aspects of the implementation strategies given space limitations. The availability of journals’ online supplemental material should be considered in future research; however, we recognize that few journals subject online supplements to peer review. Fifth, our focus on the effectiveness of implementation strategies compelled us to focus on rigorous designs that minimize threats to internal validity; however, we recognize that there is much to learn from implementation research that uses different study designs (Berwick, 2008; Wensing, Eccles, & Grol, 2005). Finally, the conceptual frameworks we used to characterize the implementation studies (Proctor et al., 2009) and strategies (Damschroder et al., 2009) have not been fully established empirically, which is the case for most theories, models, and frameworks in dissemination and implementation science (Grol et al., 2007). Despite this limitation, we found the models to be very helpful in facilitating a greater understanding of the overall study designs as well as the intended targets of the implementation strategies.

Conclusion

There is a clear need for more rigorous research on the effectiveness of implementation strategies, and we join Brekke, Ell, & Palinkas (2007) in urging the social work research community to take a leadership role in these efforts. Future work in this area should prioritize the integration of conceptual models and theories in the conceptualization and design of research, utilize a broader range of implementation outcomes, and test multifaceted a wider range of strategies that address multiple levels of the implementation context. Yet, the need for more comprehensive implementation strategies must be balanced with the requirement that they be acceptable, feasible, and cost-effective if they are to be adopted in real-world systems of care. Assessing the cost effectiveness of implementation strategies, and integrating stakeholder preferences regarding strategies is an important line of future research. Finally, this research has important implications for future implementation practice. It suggests that no single implementation strategy represents a “magic bullet” (Oxman, Thomson, Davis, & Haynes, 1995), and that implementation stakeholders would be wise to consider the challenges and barriers specific to their practice context, tailoring implementation strategies to address them.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by: a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Fellowship for the Promotion of Child Well-Being, NIMH T32 MH019960, NIH TL1 RR024995, UL1 RR024992, and NIMH F31 MH098478 to BJP; NIH UL1 RR024992 and NIMH P30 MH068579 to EKP; and NIDA T32DA015035 and NIAAA F31AA021034 to JEG. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the NIMH funded Seattle Implementation Research Conference on October 14, 2011 and the Annual Meeting of the Society for Social Work and Research on January 13, 2012.

Contributor Information

Byron J. Powell, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis.

Enola K. Proctor, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis.

Joseph E. Glass, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- Aarons GA, Horowitz JD, Dlugosz LR, Ehrhart MG. The role of organizational processes in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 128–153. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implementation Science. 2013;8(52):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Hearld LR. Methods and metrics challenges of delivery-systems research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(15):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Report of the 2005 presidential task force on evidence-based practice. Washington, D. C: 2005. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Murray P, Wells KB. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Atkins MS, Frazier SL, Leathers SJ, Graczyk PA, Talbott E, Jakobsons L, Bell CC. Teacher key opinion leaders and mental health consultation in low-income urban schools. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(5):905–908. doi: 10.1037/a0013036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Azocar F, Cuffel B, Goldman W, McCarter L. The impact of evidence-based guideline dissemination for the assessment and treatment of major depression in a managed behavioral health care organization. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2003;30(1):109–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02287816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Lee BR, Lindsey MA, Collins KS, Strieder F, Chorpita BF, Sparks JA. Evidence-based practice at a crossroads: The emergence of common elements and factors. Research on Social Work Practice. 2012;22(1):108–119. doi: 10.1177/1049731511408440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Cross W, Dorsey S. Show me, don’t tell me: Behavioral rehearsal as a training and analogue fidelity tool. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bert SC, Farris JR, Borkowski JG. Parent training: Implementation strategies for Adventures in Parenting. J Primary Prevent. 2008;29:243–261. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ. 1996;312(9):619–622. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182–1184. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkel RC, Hall LL, Lane T, Cohan K, Miller J. Consumers and families as partners in implementing evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;26:867–881. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(03)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, van der Weijden T, Wensing M, Grol R. Tailoring quality improvement interventions to identified barriers: A multiple case analysis. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007;13:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Ell K, Palinkas LA. Translational science at the National Institute of Mental Health: Can social work take its rightful place? Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17(1):123–133. doi: 10.1177/1049731506293693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(37):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare. 2008;87(5):27–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Baker MJ, Baucom DH, Beutler LE, Calhoun KS, Crits-Christoph P, Woody SR. Update on empirically validated therapies, II. The Clinical Psychologist. 1998;51(1):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Becker KD, Daleiden EL. Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):647–652. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318033ff71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Data collection checklist. 2002a:1–30. Retrieved from http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf.

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Data abstraction form. 2002b Retrieved from http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-author-resources.

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. n.d Retrieved April 15, 2013, from http://epoc.cochrane.org.

- Colquhoun HL, Brehaut JC, Sales A, Ivers N, Grimshaw J, Michie S, Eva KW. A systematic review of the use of theory in randomized controlled trials of audit and feedback. Implementation Science. 2013;8(66) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. The Academy of Management Journal. 1991;34(3):555–590. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(50):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implementation Science. 2010;5(14):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DA, Davis N. Educational interventions. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert L, Amaya-Jackson L, Markiewicz JM, Kisiel C, Fairbank JA. Use of the breakthrough series collaborative to support broad and sustained use of evidence-based trauma treatment for children in community practice settings. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39 doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, Armstrong D, Baker R, Cleary K, Davies H, Davies S, Sibbald B. An implementation research agenda. Implementation Science. 2009;4(18):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL, Schoenbaum M. The role of economic incentives in improving the quality of mental health care. In: Jones AM, editor. The Elgar Companion to Health Economics. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (No. FMHI Publication #231) (No. No. FMHI Publication #231) Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]