Abstract

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are involved in approximately 5% of all human cancer. Although initially recognized for causing nearly all cases of cervical carcinoma, much data has now emerged implicating HPVs as a causal factor in other anogenital cancers as well as a subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), most commonly oropharyngeal cancers. Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated that patients with HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) have improved survival compared to patients with HPV– cancers. Furthermore, epidemiological evidence shows the incidence of OPSCC has been steadily rising over time in the United States. It has been proposed that an increase in HPV-related OPSCCs is the driving force behind the increasing rate of OPSCC. Although some studies have revealed an increase in HPV+ head and neck malignancies over time in specific regions of the United States, there has not been a comprehensive study validating this trend across the entire country. Therefore, we undertook this meta-analysis to assess all literature through August 2013 that reported on the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC for patient populations within the United States. The results show an increase in the prevalence of HPV+ OPSCC from 20.9% in the pre-1990 time period to 51.4% in 1990–1999 and finally to 65.4% for 2000–present. In this manner, our study provides further evidence to support the hypothesis that HPV-associated OPSCCs are driving the increasing incidence of OPSCC over time in the United States.

Introduction

Over the past 25 years, human papillomaviruses (HPVs) have been discovered to cause approximately 5% of all human cancer.1 They are etiologically associated with nearly all cervical carcinomas,2 and significant data has emerged revealing the importance of HPVs in other anogenital cancers3 as well as head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs). Although HPV can be detected in numerous aerodigestive cancers of the head and neck, it is most prevalent in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC).4,5 The discovery of HPV as a causative agent in HNSCC represents an important shift in the epidemiology of this cancer. Historically, patients with HNSCC were older and had extensive tobacco and alcohol use histories. In contrast, patients with HPV+ HNSCC tend to be younger and have risk factors classically associated with cervical cancer, including a high number of sexual partners, an early age of first sexual encounter, and prior sexually transmitted infections.6,7

HNSCC serves as a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, representing the sixth most common cancer.8 The standard of care (SOC) for patients with HNSCC includes a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, all of which can lead to significant acute and long-term consequences. In clinical trials, patients with HPV+ tumors have consistently demonstrated improved response to treatment compared to patients with HPV– cancers.9−13 Thus, HPV status represents an independent and important prognostic factor in OPSCC. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated distinct molecular differences between HPV+ and HPV– HNSCCs, which likely underlie their differential response to treatment.14−16 Currently, the SOC treatment for HNSCC is the same regardless of HPV status.17,18 Because HPV+ HNSCC is now recognized to be a distinct disease from HPV– HNSCC, there is a move within clinical oncology to tailor treatment on the basis of the HPV status of the patient’s cancer.

To evaluate the rationale underlying the drive to stratify HNSCC treatment by HPV status, it is prudent to investigate the emergence of HPV as an etiological factor in HNSCC. Gissmann et al. first described HPV presence in the head and neck region in 1982 when they noted HPV DNA in patients with laryngeal papillomas.19 Syrjanen et al. then detected HPV antigens in oral squamous cell lesions in 1983.20 The first mention of HPV in the oropharynx, specifically the palatine tonsils, was documented in 1989 when Brandsma and Abramson showed the presence of HPV16 DNA in two of seven tonsillar squamous cell carcinomas.21 Since that time, an abundance of data has surfaced implicating HPVs in the oncogenesis of HNSCC, predominantly OPSCC.22−24 One large meta-analysis examined worldwide publications through 2004 employing PCR-based methods for the detection of HPV, and it showed a HPV prevalence of 35.6% in the oropharynx and 23.5% at other oral cavity sites.25 However, this study did not determine if the prevalence of HPV+ cancers was static or changed over time.

Numerous groups have examined the prevalence of HPV in HNSCCs across time. Chaturvedi et al. evaluated the incidence of head and neck cancer between 1973 and 2004 from nine SEER databases.26 They did not carry out any molecular analyses to identify patients with HPV+ cancers, but they instead stratified patients into either HPV-related or -unrelated groups on the basis of the anatomic site of their cancer (oropharynx versus all other sites, respectively). Their study revealed a statistically significant increase in HPV-related cancers and a decrease in HPV-unrelated cases.26 In another study, they evaluated 271 oropharyngeal cancer cases from three SEER databases for the presence of HPV DNA and found that HPV prevalence increased from 16.3% during 1984–1989 to 72.7% for 2000–2004.27 Similarly, Ernster et al. assessed incidence data for oropharyngeal cancer from 1980 to 1990 compared to 1991–2001 for Colorado and the United States via the Colorado Central Cancer Registry and the SEER program, respectively.28 They showed an increased incidence of oropharyngeal cancers in both Colorado and the United States between the two time periods. Furthermore, they analyzed oropharyngeal cancer specimens from 72 patients in one county in Colorado and demonstrated a rise in HPV prevalence from 20% in 1980–84 to 82% in 2000–04.28 Simard et al. revealed a similar trend of increasing incidence for oropharyngeal cancer in white men and women of 4.4 and 1.9% per year, respectively, between 1999 and 2008 on the basis of data from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries.29

Thus, on the basis of the current literature, it is evident that OPSCC is on the rise in the United States. Interestingly, Chaturvedi et al. revealed the number of OPSCC cases in men and women combined has surpassed the number of cervical cancer cases in women in recent years.27 It is imperative to understand the driving force behind the increasing incidence of OPSCC. The current belief is that a steadily rising rate of HPV-associated malignancies is driving the incidence of OPSCC, but the majority of studies solely examine a cross section of individuals at one time and a single location in the United States. Therefore, we undertook this meta-analysis to evaluate changes in the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC across the United States over the last several decades. Our results demonstrate a highly statistically significant increase in the prevalence of HPV+ OPSCCs across the three time periods analyzed: pre-1990, 1990–1999, and 2000–present. This analysis provides further evidence for the hypothesis that the rising incidence of OPSCC in the United States is a result of HPV-associated malignancies. Thus, it is important moving forward to consider HPV status in clinical trials for HNSCC, particularly OPSCC.

Experimental Procedures

Article Selection

The NIH PubMed search engine was used to identify publications via the following keyword searches: “HPV prevalence in oropharyngeal cancer”, “HPV and tonsillar cancer”, and “HPV prevalence in tonsillar cancer”. Titles and abstracts were examined to identify articles through August 2013 that presented data on the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in situ hybridization (ISH), p16 immunohistochemistry (IHC), or other methods for HPV detection. Any articles that fit within the scope of these broad criteria were selected for the assessment of the entire study. Additional relevant papers were identified by methodically evaluating the reference sections of other review articles7,30 and meta-analyses.25,31,32 In a similar manner to the process described above, abstracts were screened to identify articles reporting on the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC based on molecular detection methods. Articles meeting these criteria were then subjected to a more complete and thorough review.

Exclusion Criteria

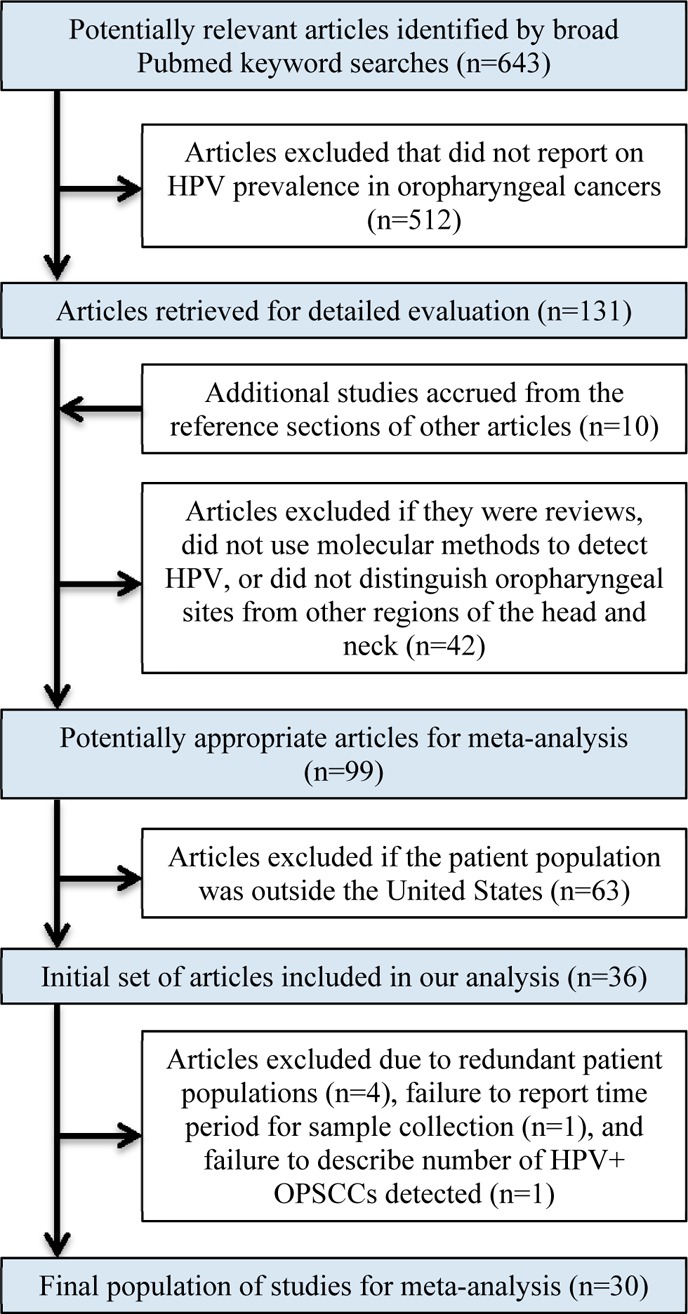

Studies were initially excluded for the following reasons: review articles, papers in which molecular methods to detect HPV were not employed, failure to distinguish oropharyngeal cancers from other oral cavity sites, and patient populations outside the United States. To be evaluated in the context of our meta-analysis, articles required a minimum amount of data. This included a description of the type of samples analyzed, detection method, time period of sample collection, number of HPV+ OPSCCs, and total number of OPSCCs analyzed (Table S1). However, five articles did not report the sample collection time period,11,23,33−35 and two did not describe the number of HPV+ OPSCCs detected.27,36 Therefore, we e-mailed authors from these seven articles to glean this information (if available), which allowed us to increase the number of articles included in our analysis. Furthermore, four other articles21,37−39 reported HPV positivity at some sites in the oropharynx such as the tonsil, but they then provided information for broader anatomic areas (tongue, pharynx, and palate) that could have included additional oropharyngeal samples. We e-mailed these authors to ask them to breakdown tongue into base of tongue (oropharynx) versus oral tongue, pharynx into lateral/posterior pharyngeal walls (oropharynx) versus other pharynx, and palate into soft palate (oropharynx) versus hard palate. If they provided us with this information, then we could increase the sample size for that article. However, if the authors did not reply or could not breakdown these anatomic areas further, then we still included data from these articles by utilizing information for samples in their study that definitively arose from the oropharynx or anatomic subsites within the oropharynx and not including samples from broader anatomic regions. Overall, we received responses related to eight of the 11 articles, and the insight gained from these correspondences is detailed in the footnotes of Table S1. Lastly, additional articles were excluded because of redundant patient populations (here, we included the articles reporting on the larger number of patients), failure to provide the time period for their sample collection, and failure to report the number of HPV+ OPSCCs detected (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the exclusion and inclusion of articles used in our meta-analysis.

Data Abstraction

Data collected from all articles included title, authors, journal, year published, country, description of patients, anatomical sites of cancers analyzed, type of sample (formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded versus fresh frozen), HPV detection method, sample collection period, overall number of head and neck cancers analyzed, and number of cancers that were HPV+. We stratified the head and neck cancers from these studies into oropharyngeal (tonsil, base of tongue, soft palate, lateral, and posterior pharyngeal walls) and nonoropharyngeal (all other sites). Our final data included the overall number of HPV+ OPSCCs out of the total number of OPSCCs analyzed by a specific article and stratified by the time period from which the samples originated.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed with the goal of estimating the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC in the United States from 1980 through August 2013. HPV prevalence was defined as the number of patients with OPSCC whose tumors demonstrated the presence of HPV divided by the total number of OPSCCs analyzed. Linear regression was used on the basis of log-transformed prevalence values and was weighted by the number of OPSCCs assessed in each study. HPV prevalence was subsequently stratified by year on the basis of the midpoint of the first and last years of the study collection period.32 As shown in Table S1, three articles separated their samples into multiple time periods. In this manner, we had a total of 38 data points from the 30 studies included in our analysis (Figure 2A). The midpoint year was used in the model as a categorical variable grouped as pre-1990, 1990–1999, and 2000–present. In addition, we evaluated the prevalence of HPV based on the method employed for HPV detection. Only studies with a midpoint year of 1997 or later that used PCR- or ISH-based methods were included in this analysis. To evaluate whether HPV prevalence differed by time period or method of detection, two-sided 95% confidence intervals were calculated and adjusted using the Bonferroni method. All analyses were performed using the procedure PROC GLM from SAS/STAT software (version 9.3).

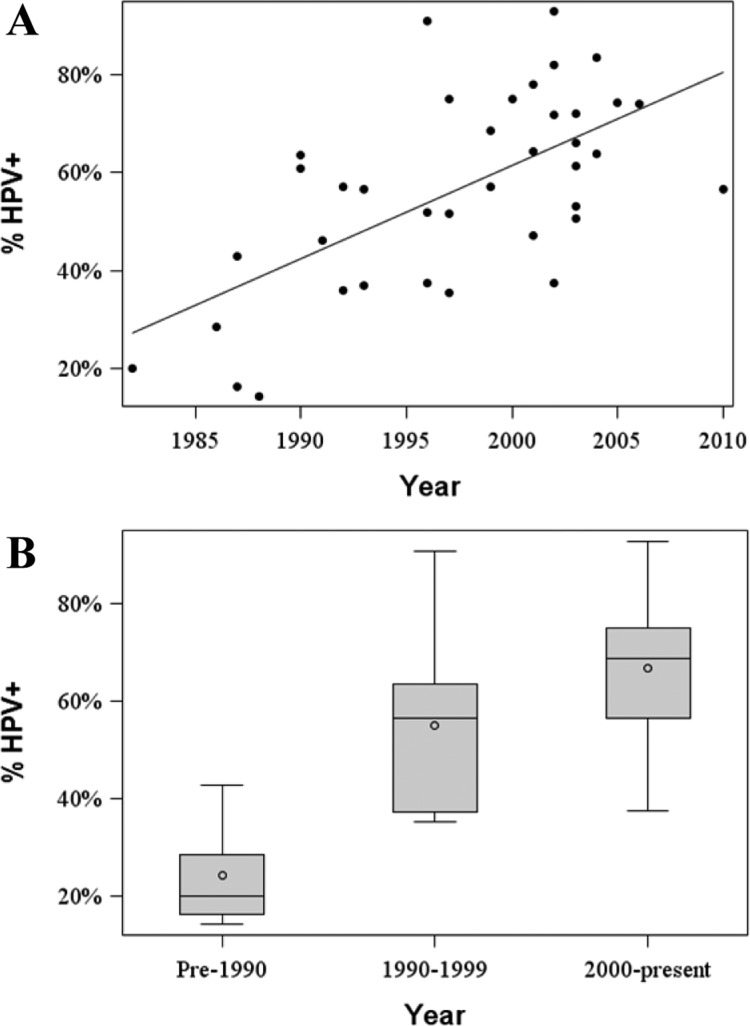

Figure 2.

Prevalence of HPV in OPSCC over time in the United States. (A) Scatterplot demonstrating the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC reported by each article included in our analysis. The median year for the study’s sample collection period was used as the time point. (B) Boxplots of the HPV prevalence in OPSCC stratified into three time periods: pre-1990, 1990–1999, and 2000–present.

Results

Article Selection and Characteristics

In all, 643 articles were identified from our broad PubMed searches. After examining titles and abstracts to select articles that reported on the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC or at anatomic subsites in the oropharynx, 512 were excluded. An additional 10 studies assessing patients from the United States were identified by evaluating the reference sections of other articles.7,25,30−32 Of the 141 articles that underwent full review, 42 were excluded because they were either review articles, did not employ molecular techniques to detect HPV, or did not distinguish anatomical sites of the oropharynx from other areas within the head and neck. Subsequently, 63 articles were excluded because they reported on patient populations outside the United States. Thus, we were left with 36 articles. Next, as detailed in the Experimental Procedures, we contacted authors from 11 studies to gather further information about their work (if available) that allowed us to either (a) include articles that initially would have met exclusion criteria (specifically, did not report sample collection time period (n = 5) or number of HPV+ OPSCCs detected (n = 2)) or (b) increase the sample size for a particular article by further stratifying specific anatomic areas: tongue, pharynx, and palate (n = 4). We received responses related to four of five articles in which the authors were queried regarding the time period for their sample collection,11,23,34,35 two of two articles in which the authors were queried regarding the number of HPV+ OPSCCs detected27,36 (only one had the requested data27), and two of four in which the authors were queried regarding stratification of anatomic sites38,39 (again, only one group could provide this information38). More detailed descriptions of the data gathered from these authors are described in the footnotes of Table S1. Importantly, this correspondence led to the identification of additional articles that needed to be excluded because of redundant patient populations (n = 4)11,23,40,41 (here, we included the articles reporting on the larger number of patients). Lastly, two more articles were excluded: one for failing to provide the time period for their sample collection33 and another that did not report the number of HPV+ OPSCCs detected.36 Ultimately, we included 30 articles in this meta-analysis (Figure 1 and Table S1).

The 30 articles in our study reported on the HPV prevalence in 3428 patients with HNSCC. There were 2099 patients with OPSCC. On average, each article presented on the HPV status for 70 (range 7–323) patients with OPSCC. Twenty-three studies analyzed formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumors, five used fresh frozen tissue, and two used a combination of FFPE and fresh frozen samples. A variety of molecular methods were utilized for the detection of HPV. In some studies, multiple methods were employed to compare their efficacy. For our analysis, we collected data on the basis of the method utilized to make the final decision on HPV status. In this context, 18 studies used PCR-based methods, eight, ISH, two, PCR with flight mass spectroscopy (Attosense HPV Test), one, Southern blot, and one, a combination of p16 IHC followed by ISH and PCR. Specific data for each article can be found in Table S1. Importantly, these studies reported on patients from across the United States including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Washington.

HPV Prevalence in Oropharyngeal Cancer

The prevalence of HPV in OPSCC (HPV prevalence) in each study group is displayed in Figure 2A as a function of the median year of the sample collection period. To assess the relationship between HPV+ OPSCCs and time in greater detail, we divided the articles into three time periods on the basis of the median year of the sample collection period: pre-1990, 1990–1999, and 2000-present. Figure 2B displays the raw data for the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC across the three time periods. On the basis of our statistical analysis, the mean prevalence of HPV was 20.9% (95% CI: (11.8, 37.0%)) in pre-1990, 51.4% (95% CI: (45.4, 58.2%)) from 1990 to 1999, and 65.4% (95% CI: (60.5, 70.7%)) for 2000–present (Table 1). The differences in HPV prevalence values across the three time periods, pre-1990, 1990–1999, and 2000–present, were found to be highly statistically significant, with p values of 0.004 (pre-1990 vs 1990–1999), 0.002 (1990–1999 vs 2000–present), and <0.001 (pre-1990 vs 2000–present).

Table 1. Prevalence of HPV in OPSCC in the United States.

| time period | number of studies | total number of OPSCCs analyzed | mean HPV+ OPSCC prevalence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pre-1990 | 5 | 82 | 20.9 (11.8, 37.0) |

| 1990–1999 | 15 | 684 | 51.4 (45.4, 58.2) |

| 2000–present | 18 | 1333 | 65.4 (60.5, 70.7) |

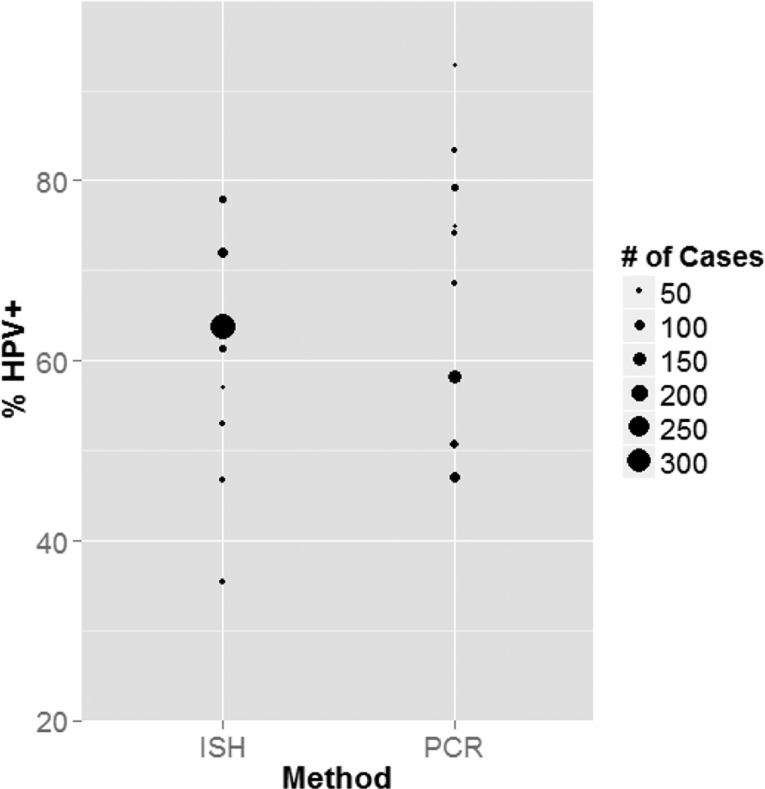

Next, we investigated whether the detection method utilized led to a difference in HPV prevalence. Because the majority of studies employed either HPV DNA PCR- or ISH-based methods, we compared HPV prevalence between these two categories. The first year ISH was employed in these studies was 1997. Therefore, we restricted our evaluation to studies from 1997 to the present because, had we included studies prior to 1997, we would have artificially lowered the prevalence of HPV detected by PCR because HPV prevalence was lower in earlier populations. Overall, we compared eight articles reporting on 718 OPSCC specimens via ISH and nine articles evaluating 501 OPSCC samples by PCR (Table 2). The observed HPV prevalence value from each article is displayed in Figure 3, with the relative size of the data point representing the number of OPSCCs analyzed. By weighting the studies on the basis of the number of OPSCCs analyzed, the estimated HPV prevalence was 63.1% (95% CI: (55.7, 71.6%)) and 63.3% (95% CI: (54.4, 73.6%)) for ISH and PCR, respectively. Thus, there was no statistically significant difference between the mean HPV prevalence detected by ISH compared to PCR (p value = 0.98).

Table 2. Frequency of HPV+ OPSCC Detected by PCR versus ISH.

| detection method | number of studies | total number of OPSCCs analyzed | mean HPV+ OPSCC prevalence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | 8 | 718 | 63.1 (55.7, 71.6) |

| PCR | 9 | 501 | 63.3 (54.4, 73.6) |

Figure 3.

Frequency of HPV+ OPSCC detected by PCR versus ISH. The prevalence of HPV in OPSCC for articles with a median sample collection year from 1997 to the present employing ISH- or PCR-based methods for HPV detection. The relative size of the data point circle is dependent on the number of OPSCCs analyzed in the article.

Discussion

Numerous groups have noted a steady rise in the incidence of OPSCC in the United States.26,28,29 It is now well-accepted that HPV represents an etiologic agent in a proportion of OPSCCs,44 and it has been hypothesized that the driving force behind the rising incidence of OPSCC in the United States is an increase in HPV-related malignancies. To date, there has not been a meta-analysis focusing on the trend of HPV prevalence in OPSCC across the United States over time. By analyzing all of the published literature reporting on patient populations in the United States on this topic, we have demonstrated a clear increase in the proportion of HPV-positive OPSCCs since 1980 until present day. Separating the samples into three discrete time periods, pre-1990, 1990–1999, and 2000–present, the mean prevalence of HPV detected in OPSCC rose from 20.9 to 51.4 to 65.4% (Table 1), respectively. This analysis provides further evidence that HPV represents the likely culprit underlying the increasing incidence of OPSCC in the United States. Moreover, our results are in agreement with another meta-analysis that assessed the global prevalence of HPV across time, although that article did not distinguish the United States from North America.32

Many aspects of our study make these results robust. First, we made a strong and concerted effort to exclude any articles with redundant patient populations. This was accomplished by correspondence with authors who published multiple articles on this subject. We discovered this was a relatively common occurrence, and it would have been difficult to recognize this problem without direct discussions with the authors. In addition, we gathered new information from multiple authors, which allowed us to expand the number of articles included in our study (Table S1). Furthermore, we did not exclude articles on the basis of sample size, but instead, we employed statistical models to weight studies on the basis of the number of OPSCC specimens analyzed.

Despite these efforts, there are, of course, limitations to this analysis. First, we focused on the published literature and did not delve into unpublished data. In this manner, it is possible we have introduced publication bias into this work. Another potential area for concern is that the articles examined a wide range of specimens from varying years and therefore the less frequent detection of HPV in earlier time periods could simply be a consequence of reduced quality of those samples. However, most of the studies (13 out of 18) that included specimens from more than 10 years prior to the publication date carried out quality-control analyses on all of their samples using PCR amplification of beta-globin, beta-actin, or another housekeeping gene to determine whether the tissue was of high enough quality to undergo further analysis.27,28,39,44−52 Likewise, six of the seven articles with samples from 15 years or greater before the year of publication carried out similar quality-control measurements.27,28,39,45−47 Thus, poor quality of older samples should not have significantly affected our data because a high proportion of these articles verified the integrity of their tissue prior to HPV detection. Along the same line, it is possible that changes in the sensitivity of HPV detection methods over time could have influenced this analysis. Two recently published articles (201127 and 200728) evaluated samples from the 1980s through early 2000s. They divided their specimens into four or five consecutive time periods on the basis of the year that the samples originated in order to assess for any changes in HPV prevalence across time. Importantly, they performed quality-control evaluations, as described above, to ensure that degradation of tissue did not influence their results.27,28 Utilizing present-day HPV detection methods, both articles revealed a rising prevalence of HPV+ OPSCCs across the different time periods, consistent with the pattern seen in our meta-analysis. Therefore, it is unlikely that changes in the sensitivity of HPV detection methods over the time period in which the included studies were performed confound the interpretation of our meta-analysis. Lastly, the data was collected in a retrospective fashion, and the studies were carried out by numerous groups utilizing a variety of criteria for patient inclusion/exclusion, gold standards for determining HPV-positivity, and many different assays for HPV detection.

The majority of studies in this analysis used HPV DNA ISH- or PCR-based methods for HPV detection. Although there was not a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of HPV detected by ISH or PCR (Table 2), it is important to assess the commonly utilized methods for HPV detection (reviewed in ref (53)). For PCR, there a number of primer sets available that target degenerate sequences common in multiple HPV genotypes or gene regions specific to certain HPV genotypes such as HPV 16 (implicated in almost 90% of HPV-associated OPSCCs),25 18, 31, 33, and others. PCR assays are highly sensitive and can detect a small quantity of HPV DNA. However, PCR cannot distinguish whether the HPV originated within tumor or adjacent nontumor cells, leading to the concern that PCR alone could lead to false positive results. Similar to PCR, there are numerous molecular probes available for HPV DNA ISH. One advantage to ISH is that it demonstrates the cellular location of the HPV. However, a key pitfall to both HPV DNA PCR- and ISH-based methods is that they determine solely the presence of HPV DNA in the sample, but this does not indicate if the virus is transcriptionally active. p16 IHC has been used in the clinical realm as a surrogate for transcriptionally active HPV infections. Briefly, E7, a vital HPV oncogene, leads to downregulation of the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma (Rb). A decrease in Rb levels/activity leads to a rise in p16.54 Overexpression of p16 has been demonstrated to be consistent with HPV infection in OPSCC.55,56 However, this assay lacks specificity for HPV, and there exists a subset of p16-positive/HPV DNA-negative tumors.57 For this reason, multiple studies have examined using a multistep process of p16 IHC (highly sensitive) followed by HPV DNA ISH (highly specific) to demonstrate both the presence and activity HPV.58,59 This two-step process compared well to HPV E6/E7 RT-PCR, which was utilized as the gold standard in these studies. Lastly, a novel E6/E7 RNA ISH assay was evaluated in two studies, and both indicate that it is very sensitive and specific to the presence of transcriptionally active HPV.23,60 Given the wide array of available assays, there is a clear need to establish standards for HPV detection.61

The increasing burden of HPV+ OPSCC raises an important public health issue: will vaccinating against HPV decrease the incidence of OPSCC in the future? Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of two vaccines against HPV: Gardasil (targets HPV subtypes 6, 11, 16, and 18) and Cervarix (targets HPV subtypes 16 and 18). Both vaccines have demonstrated the ability to decrease rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in large, randomized clinical trials in women.62,63 However, vaccine efficacy specifically against oropharyngeal cancer is not clear and has yet to be examined in the literature. Considering that more than 90% of OPSCCs are caused by HPV-16 and 18,25 it is likely that these vaccines would reduce the future incidence of OPSCC. This is an especially important issue for males because they bear the greater burden of this disease.4,29 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routine vaccination of males at age 11 or 12 (can be started at 9), with additional recommendations for unvaccinated males aged 13–21 and 22–26.64 A national survey of 13–17 year old males in 2010 found the vaccination rate was quite low, with less than 2% receiving at least one dose of the vaccine.65 Clearly, further efforts are needed to increase the vaccination rate among males.66 In the mean time, we expect the role of HPV in OPSCC to continue its upward trend for at least the next few decades because there is a long lag time between infection and cancer development.67 Thus, it is important to continue investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying this cancer as well as different treatment options for patients.

Indeed an important value of assessing OPSCCs for the presence or absence of HPV is the prognostic information that this carries for patients.9−13 Patients with HPV+ OPSCC have significantly improved outcomes compared to those with HPV– OPSCC. This is likely due to underlying molecular differences between HPV+ and HPV– cancers.14−16 On the basis of the improved survival outcomes seen in patients with HPV+ OPSCC, the major cooperative groups that enroll HNSCC patients have embarked on a series of studies specifically targeting these patients. However, pending these results, there is currently no difference in the SOC treatment for patients on the basis of the HPV status of their cancer. Many of these ongoing trials attempt to maintain the improved survival outcomes for patients with HPV+ cancers while minimizing treatment-related morbidity. Currently, these trials are focusing on using relatively standard treatments for patients with HPV+ OPSCC (reviewed in ref (68)), but in the future, we predict that treatments targeting either the viral oncogenes or critical molecular pathways may play a role in therapy.

In addition to these important clinical trials, a number of groups are attempting to understand the biology of HPV+ cancers better using both in vitro and in vivo model systems. Our own groups have developed transgenic models of HPV+ oral cancer in mice as well as a patient-derived xenograft system for studying human tumors.14,69 These preclinical animal models as well as established cell lines derived from human head and neck cancers70 can be used to evaluate the efficacy of novel therapies, to test unique combinations of treatment, and to identify informative biomarkers that can be validated in prospective clinical trials. Testing for and identifying patients with HPV+ cancers will play a critical role in the care of patients with OPSCC, and this should be considered a standard part of the multidisciplinary care for patients with head and neck cancer.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. Anil Chaturvedi, James Lewis, Maura Gillison, Francis Worden, Steve Schwartz, Sharon Wilcyznski, James Rocco, Anthony Nichols, and Seth Schwartz for corresponding with us about their articles and for providing additional information for our meta-analysis. We also acknowledge Jennifer L. Kraninger for editing the manuscript and helping to design the table of contents graphic.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- OPSCC

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ISH

in situ hybridization

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- FFPE

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- CI

confidence interval

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- SOC

standard of care

- U.S. FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

Supporting Information Available

Detailed information that we extracted from all 30 articles in our meta-analysis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (CA022443) and the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center/Wisconsin Institutes of Discovery/Morgridge Institute.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- (2007) Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 90, 1–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz N., Bosch F. X., de Sanjose S., Herrero R., Castellsagué X., Shah K. V., Snijders P. J., Meijer C. J., International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group (2003) Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachow K. R.; Ostrow R. S.; Bender M.; Watts S.; Okagaki T.; Pass F.; Faras A. J. (1982) Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in anogenital neoplasias. Nature 300, 771–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandberg D. P.; Bhargava R.; Badin S.; Cullen K. J. (2013) The role of human papillomavirus in nongenital cancers. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 63, 57–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison M. L.; Shah K. V. (2003) Chapter 9: Role of mucosal human papillomavirus in nongenital cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza G.; Kreimer A. R.; Viscidi R.; Pawlita M.; Fakhry C.; Koch W. M.; Westra W. H.; Gillison M. L. (2007) Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1944–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison M. L.; Koch W. M.; Shah K. V. (1999) Human papillomavirus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Are some head and neck cancers a sexually transmitted disease?. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 11, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (2011) Cancer Facts and Figures, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA.

- Rischin D.; Young R. J.; Fisher R.; Fox S. B.; Le Q. T.; Peters L. J.; Solomon B.; Choi J.; O’Sullivan B.; Kenny L. M.; McArthur G. A. (2010) Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4142–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M. R.; Lorch J. H.; Goloubeva O.; Tan M.; Schumaker L. M.; Sarlis N. J.; Haddad R. I.; Cullen K. J. (2011) Survival and human papillomavirus in oropharynx cancer in TAX 324: A subset analysis from an international phase III trial. Ann. Oncol. 22, 1071–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols A. C.; Faquin W. C.; Westra W. H.; Mroz E. A.; Begum S.; Clark J. R.; Rocco J. W. (2009) HPV-16 infection predicts treatment outcome in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 140, 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong A. M.; Dobbins T. A.; Lee C. S.; Jones D.; Harnett G. B.; Armstrong B. K.; Clark J. R.; Milross C. G.; Kim J.; O’Brien C. J.; Rose B. R. (2010) Human papillomavirus predicts outcome in oropharyngeal cancer in patients treated primarily with surgery or radiation therapy. Br. J. Cancer 103, 1510–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang K. K.; Harris J.; Wheeler R.; Weber R.; Rosenthal D. I.; Nguyen-Tân P. F.; Westra W. H.; Chung C. H.; Jordan R. C.; Lu C.; Kim H.; Axelrod R.; Silverman C. C.; Redmond K. P.; Gillison M. L. (2010) Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strati K.; Pitot H. C.; Lambert P. F. (2006) Identification of biomarkers that distinguish human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive versus HPV-negative head and neck cancers in a mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14152–14157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafkamp H. C.; Speel E. J.; Haesevoets A.; Bot F. J.; Dinjens W. N.; Ramaekers F. C.; Hopman A. H.; Manni J. J. (2003) A subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas exhibits integration of HPV 16/18 DNA and overexpression of p16INK4A and p53 in the absence of mutations in p53 exons 5–8. Int. J. Cancer 107, 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J. O.; Hakim J.; Koch W.; van der Riet P.; Hruban R. H.; Roa R. A.; Correo R.; Eby Y. J.; Ruppert J. M.; Sidransky D. (1993) The incidence of p53 mutations increases with progression of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 53, 4477–4480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra R.; Ang K. K.; Burtness B. (2012) Management of human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative head and neck cancer. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 22, 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna H.; Olaleye O.; Licitra L. (2012) Oropharyngeal cancer - is it time to change management according to human papilloma virus status?. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 20, 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissmann L.; Wolnik L.; Ikenberg H.; Koldovsky U.; Schnürch H. G.; zur Hausen H. (1983) Human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 DNA sequences in genital and laryngeal papillomas and in some cervical cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 560–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjanen K. J.; Pyrhonen S.; Syrjanen S. M.; Lamberg M. A. (1983) Immunohistochemical demonstration of human papilloma virus (HPV) antigens in oral squamous cell lesions. Br. J. Oral Surg. 21, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandsma J. L.; Abramson A. L. (1989) Association of papillomavirus with cancers of the head and neck. Arch. Otolaryngol., Head Neck Surg. 115, 621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houten V. M.; Snijders P. J.; van den Brekel M. W.; Kummer J. A.; Meijer C. J.; van Leeuwen B.; Denkers F.; Smeele L. E.; Snow G. B.; Brakenhoff R. H. (2001) Biological evidence that human papillomaviruses are etiologically involved in a subgroup of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 93, 232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukpo O. C.; Flanagan J. J.; Ma X. J.; Luo Y.; Thorstad W. L.; Lewis J. S. Jr. (2011) High-risk human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA detection by a novel in situ hybridization assay strongly correlates with p16 expression and patient outcomes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 35, 1343–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C. H.; Gillison M. L. (2009) Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer: Its role in pathogenesis and clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 6758–6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreimer A. R.; Clifford G. M.; Boyle P.; Franceschi S. (2005) Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol., Biomarkers Prev. 14, 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi A. K.; Engels E. A.; Anderson W. F.; Gillison M. L. (2008) Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi A. K.; Engels E. A.; Pfeiffer R. M.; Hernandez B. Y.; Xiao W.; Kim E.; Jiang B.; Goodman M. T.; Sibug-Saber M.; Cozen W.; Liu L.; Lynch C. F.; Wentzensen N.; Jordan R. C.; Altekruse S.; Anderson W. F.; Rosenberg P. S.; Gillison M. L. (2011) Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 4294–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernster J. A.; Sciotto C. G.; O’Brien M. M.; Finch J. L.; Robinson L. J.; Willson T.; Mathews M. (2007) Rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer and the role of oncogenic human papilloma virus. Laryngoscope 117, 2115–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard E. P.; Ward E. M.; Siegel R.; Jemal A. (2012) Cancers with increasing incidence trends in the United States: 1999 through 2008. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 62, 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal L.; Gillison M. L. (2008) Human papillomavirus in HNSCC: Recognition of a distinct disease type. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 22, 1125–1142vii.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. S.; Johnstone B. M. (2001) Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis, 1982–1997. Oral Surg., Oral Med., Oral Pathol., Oral Radiol., Endodontol. 91, 622–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna H.; Beech T.; Nicholson T.; El-Hariry I.; McConkey C.; Paleri V.; Roberts S. (2013) Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer–systematic review and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck 35, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S.; Cao D.; Gillison M.; Zahurak M.; Westra W. H. (2005) Tissue distribution of human papillomavirus 16 DNA integration in patients with tonsillar carcinoma. Clin. Cancer. Res. 11, 5694–5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhry C.; Westra W. H.; Li S.; Cmelak A.; Ridge J. A.; Pinto H.; Forastiere A.; Gillison M. L. (2008) Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden F. P.; Kumar B.; Lee J. S.; Wolf G. T.; Cordell K. G.; Taylor J. M.; Urba S. G.; Eisbruch A.; Teknos T. N.; Chepeha D. B.; Prince M. E.; Tsien C. I.; D’Silva N. J.; Yang K.; Kurnit D. M.; Mason H. L.; Miller T. H.; Wallace N. E.; Bradford C. R.; Carey T. E. (2008) Chemoselection as a strategy for organ preservation in advanced oropharynx cancer: Response and survival positively associated with HPV16 copy number. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 3138–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. R.; Yueh B.; McDougall J. K.; Daling J. R.; Schwartz S. M. (2001) Human papillomavirus infection and survival in oral squamous cell cancer: a population-based study. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 125, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra W. H.; Taube J. M.; Poeta M. L.; Begum S.; Sidransky D.; Koch W. M. (2008) Inverse relationship between human papillomavirus-16 infection and disruptive p53 gene mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 366–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. M.; Daling J. R.; Doody D. R.; Wipf G. C.; Carter J. J.; Madeleine M. M.; Mao E. J.; Fitzgibbons E. D.; Huang S.; Beckmann A. M.; McDougall J. K.; Galloway D. A. (1998) Oral cancer risk in relation to sexual history and evidence of human papillomavirus infection. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1626–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz I. B.; Cook N.; Odom-Maryon T.; Xie Y.; Wilczynski S. P. (1997) Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. An association of HPV 16 with squamous cell carcinoma of Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring. Cancer 79, 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernock R. D.; El-Mofty S. K.; Thorstad W. L.; Parvin C. A.; Lewis J. S. Jr. (2009) HPV-related nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: Utility of microscopic features in predicting patient outcome. Head Neck Pathol. 3, 186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J. M.; Smith E. M.; Summersgill K. F.; Hoffman H. T.; Wang D.; Klussmann J. P.; Turek L. P.; Haugen T. H. (2003) Human papillomavirus infection as a prognostic factor in carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int. J. Cancer 104, 336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison M. L.; Koch W. M.; Capone R. B.; Spafford M.; Westra W. H.; Wu L.; Zahurak M. L.; Daniel R. W.; Viglione M.; Symer D. E.; Shah K. V.; Sidransky D. (2000) Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 709–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S. E.; Savva A.; Brissett A. E.; Gostout B. S.; Lewis J.; Clayton A. C.; McGovern R.; Weaver A. L.; Persing D.; Kasperbauer J. L. (2002) Squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsils: A molecular analysis of HPV associations. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 1093–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski S. P.; Lin B. T.; Xie Y.; Paz I. B. (1998) Detection of human papillomavirus DNA and oncoprotein overexpression are associated with distinct morphological patterns of tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 152, 145–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger P. M.; Yu Z.; Haffty B. G.; Kowalski D.; Harigopal M.; Brandsma J.; Sasaki C.; Joe J.; Camp R. L.; Rimm D. L.; Psyrri A. (2006) Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 736–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. F.; Matthews A.; Kandil D.; Adamson C. S.; Trotman W. E.; Cooper K. (2011) Discrimination of ‘driver’ and ‘passenger’ HPV in tonsillar carcinomas by the polymerase chain reaction, chromogenic in situ hybridization, and p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry. Head Neck Pathol. 5, 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews E.; Seaman W. T.; Webster-Cyriaque J. (2009) Oropharyngeal carcinoma in non-smokers and non-drinkers: A role for HPV. Oral Oncol. 45, 486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukpo O. C.; Pritchett C. V.; Lewis J. E.; Weaver A. L.; Smith D. I.; Moore E. J. (2009) Human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: Primary tumor burden and survival in surgical patients. Ann. Otol., Rhinol., Laryngol. 118, 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. A.; Basha S. R.; Reichenbach D. K.; Robertson E.; Sewell D. A. (2008) Increased viral load correlates with improved survival in HPV-16-associated tonsil carcinoma patients. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 128, 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. S. Jr.; Thorstad W. L.; Chernock R. D.; Haughey B. H.; Yip J. H.; Zhang Q.; El-Mofty S. K. (2010) p16 positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma:an entity with a favorable prognosis regardless of tumor HPV status. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 34, 1088–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mofty S. K.; Lu D. W. (2003) Prevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in squamous cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil, and not the oral cavity, in young patients: A distinct clinicopathologic and molecular disease entity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 27, 1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders P. J.; Heideman D. A.; Meijer C. J. (2010) Methods for HPV detection in exfoliated cell and tissue specimens. APMIS 118, 520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaes R.; Friedrich T.; Spitkovsky D.; Ridder R.; Rudy W.; Petry U.; Dallenbach-Hellweg G.; Schmidt D.; von Knebel Doeberitz M. (2001) Overexpression of p16(INK4A) as a specific marker for dysplastic and neoplastic epithelial cells of the cervix uteri. Int. J. Cancer 92, 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M.; Ihloff A. S.; Gorogh T.; Weise J. B.; Fazel A.; Krams M.; Rittgen W.; Schwarz E.; Kahn T. (2010) p16(INK4a) overexpression predicts translational active human papillomavirus infection in tonsillar cancer. Int. J. Cancer 127, 1595–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar A. K.; Westra W. H. (2012) p16 expression as a surrogate marker for HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma: A guide for interpretative relevance and consistency. Head Neck 34, 459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietbergen M. M.; Snijders P. J.; Beekzada D.; Braakhuis B. J.; Brink A.; Heideman D. A.; Hesselink A. T.; Witte B. I.; Bloemena E.; Baatenburg-De Jong R. J.; Leemans C. R.; Brakenhoff R. H. (2014) Molecular characterization of p16-immunopositive but HPV DNA-negative oropharyngeal carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer. 134, 2366–2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhi A. D.; Westra W. H. (2010) Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer 116, 2166–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan R. C.; Lingen M. W.; Perez-Ordonez B.; He X.; Pickard R.; Koluder M.; Jiang B.; Wakely P.; Xiao W.; Gillison M. L. (2012) Validation of methods for oropharyngeal cancer HPV status determination in US cooperative group trials. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 36, 945–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schache A. G.; Liloglou T.; Risk J. M.; Jones T. M.; Ma X. J.; Wang H.; Bui S.; Luo Y.; Sloan P.; Shaw R. J.; Robinson M. (2013) Validation of a novel diagnostic standard in HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 108, 1332–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakhuis B. J.; Brakenhoff R. H.; Meijer C. J.; Snijders P. J.; Leemans C. R. (2009) Human papilloma virus in head and neck cancer: The need for a standardised assay to assess the full clinical importance. Eur. J. Cancer 45, 2935–2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavonen J., Naud P., Salmeron J., Wheeler C. M., Chow S. N., Apter D., Kitchener H., Castellsague X., Teixeira J. C., Skinner S. R., Hedrick J., Jaisamrarn U., Limson G., Garland S., Szarewski A., Romanowski B., Aoki F. Y., Schwarz T. F., Poppe W. A., Bosch F. X., Jenkins D., Hardt K., Zahaf T., Descamps D., Struyf F., Lehtinen M., Dubin G., HPV PATRICIA Study Group (2009) Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): Final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet 374, 301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2007) Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1915–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (2011) Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 60, pp 1705–1708. [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 through 17 years–United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 60, pp 1117–1123. [PubMed]

- Azvolinsky A. (2013) Concerned about HPV-related cancer rise, researchers advocate boosting HPV vaccination rates. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 105, 1335–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers E. R.; McCrory D. C.; Nanda K.; Bastian L.; Matchar D. B. (2000) Mathematical model for the natural history of human papillomavirus infection and cervical carcinogenesis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 151, 1158–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple R. J., Harari P. M. (2013) Is radiation dose reduction the right answer for HPV-positive head and neck cancer? Oral Oncol. [Online early access.] DOI: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.09.015, Published Online: Oct 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple R. J.; Harari P. M.; Torres A. D.; Yang R. Z.; Soriano B. J.; Yu M.; Armstrong E. A.; Blitzer G. C.; Smith M. A.; Lorenz L. D.; Lee D.; Yang D. T.; McCulloch T. M.; Hartig G. K.; Lambert P. F. (2013) Development and characterization of HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumorgrafts. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple R. J.; Smith M. A.; Blitzer G. C.; Torres A. D.; Martin J. A.; Yang R. Z.; Peet C. R.; Lorenz L. D.; Nickel K. P.; Klingelhutz A. J.; Lambert P. F.; Harari P. M. (2013) Enhanced radiation sensitivity in HPV-positive head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 4791–4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.