Abstract

Rates of depression are reported to be between 22–33% in adults with HIV, which is double that of the general population. Depression negatively affects treatment adherence and health outcomes of those with medical illnesses. Further, it has been shown in adults that reducing depression may improve both adherence and health outcomes. To address the issues of depression and non-adherence, Health and Wellness (H&W) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and medication management (MM) treatment strategies have been developed specifically for youth living with both HIV and depression. H&W CBT is based on other studies with uninfected youth and upon research on adults with HIV. H&W CBT uses problem-solving, motivational interviewing, and cognitive-behavioral strategies to decrease adherence obstacles and increase wellness. The intervention is delivered in 14 planned sessions over a 6-month period, with three different stages of CBT. This paper summarizes the feasibility and acceptability data from an open depression trial with 8 participants, 16–24 years of age, diagnosed with HIV and with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) diagnosis of depression, conducted at two treatment sites in the Adolescent Trials Network (ATN). Both therapists and subjects completed a Session Evaluation Form (SEF) after each session, and results were strongly favorable. Results from The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician (QIDS-C) also showed noteworthy improvement in depression severity. A clinical case vignette illustrates treatment response. Further research will examine the use of H&W CBT in a larger trial of youth diagnosed with both HIV and depression.

Keywords: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Adherence, Health

Introduction

Higher rates of psychiatric illnesses are typically found in individuals with HIV, particularly mood disorders. In a study of an adult HIV infected clinic population, the rates of depression were between 22 to 32%, which is more than twice as high as the prevalence in a general population (Bing et al., 2001). In Bing and colleagues’ study, rates of mood disorders and anxiety tended to be more prevalent in those younger than 35, suggesting that younger age and the multiple challenges that come with adolescence and young adulthood may be risk factors for depression and/or anxiety. A study by Macdonell and colleagues (2011) also showed that youth may be tempted for various reasons to be non-adherent with their HIV medications. Depression can complicate the health status of these individuals by further reducing adherence to medical appointments and medications and negatively impacting medical outcomes, including increasing viral loads and decreasing CD4 counts (Ferrando, 2009).

Promising interventions to address the challenge of comorbid depression and HIV medication adherence have begun to emerge in adult populations. Horberg and colleagues (2008) found that depressed participants who were treated with antidepressant medication were more adherent to their HIV medication and had more effective disease management than depressed participants not treated with antidepressant medication (Horberg, 2008). Safren and colleagues (2009) have developed a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for increasing medication adherence in HIV infected adults, with promising results. This intervention has been shown to be effective in improving either depression, medication adherence, or both in HIV infected individuals with heroin addiction (Safren et al., 2009; Safren et al., 2012). Therefore, improving depression is important in order to improve overall health outcomes for individuals living with HIV. It is important to note that CBT may need to be specifically tailored to address adherence and wellness in order to impact both those issues. A study by Spirito and colleagues indicated that without CBT specifically focusing on suicidal thoughts and behaviors, these behaviors did not necessarily improve with the improvement of depression (Spirito, Esposito-Smythers, Wolff, & Uhl, 2011).

Non-adherence to the frequent medical appointments, typically recommended every three months, and daily medication regimens, is unfortunately common in youth with HIV (Macdonell et al., 2013; Malee et al., 2011). A study of adolescents with HIV who were initially adherent to medication concluded that failure to maintain adherence over 12 months was associated with younger age and depression (Murphy, 2005). In youth with HIV infection (age 16–24 years), psychological distress, primarily depression and anxiety symptoms, was found to be related to medication non-adherence and poor disease management outcomes (Naar-King, 2006). Macdonell et al. (2011) also found that in youth with HIV infection (age 16–24), non-adherence was linked to lack of social support and insufficient comprehension of the need for medication (Macdonell, Naar-King, Murphy, Parsons, & Huszti, 2011). Improving depression and medication education in this population may be important factors to increase adherence to medical treatment.

Effective treatments are available for youth with depression. Practice guidelines suggest that a combination of medication management and psychotherapy show a more rapid reduction in depressive symptoms than a single modality of treatment for moderate to severe depression in adolescents (Birmaher, Brent, Issues, & Staff, 2007; Cheung et al., 2007; Team & March, 2004). The majority of the work in psychotherapy trials in adolescents has utilized CBT (Compton et al., 2004; Weisz, McCarty, & Valeri, 2006), with several studies assessing the impact of interpersonal therapy (Brunstein-Klomek, 2007). Results have been promising in showing clinically significant improvement, which is consistent with adult outcomes ( , 2001 & Vittengl, Clark, Dunn, & Jarrett, 2007). However, there are no studies that inform practitioners about the best way to treat young individuals who are living with both HIV and depression. Due to many sociocultural factors, youth with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and non-adherence to appointments and medication, and thus, medical outcomes in this population may be compromised. Therefore, developing an approach that engages this population in treatment to reduce depressive symptoms and address adherence issues is warranted. The goal of this treatment is not only to mitigate depressive symptoms, but to foster wellness. The literature defines wellness as a process of pursuing goals, connecting with others, cultivating positive self-regard, and overall higher quality of life (Ryff &Singer, 1996). The application of wellness in treatment includes skills that promote positive affect and healthy lifestyles as opposed to treating symptoms of illness.

This study describes the development of a CBT intervention that has been tailored to youth ages 16–24 who are living with HIV and have been diagnosed with depression. The aim of this study is to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention, to inform further efforts to improve depression and health outcomes among youth living with HIV.

Manual Development

Overview of health and wellness CBT (H&W CBT)

The goal of the H&W CBT treatment is to develop effective strategies for targeted youth to reduce depression, improve adherence, and promote mental health. This treatment conceptualizes the participants from a mixed deficit and strengths model, by decreasing negative mood and cognitions of the youth targeted, while simultaneously enhancing strengths, positive experiences, mood, and cognitions of the youth (Kennard, 2010). The CBT treatment approach includes strategies to counter dysphoric mood and promote health and well-being. Although the treatment approach is primarily CBT, it also integrates motivational interviewing (MI) as needed, in order to engage the patient in treatment as well as to manage problems with adherence and/or substance abuse (Naar-King, 2011). The person centered approach of motivational interviewing can give patients insight, knowledge, and skills to strengthen their own motivation for change.

Treatment adherence is essential to promoting health outcomes, as taking medications in a timely manner is the most effective way to reduce viral load and enhance Cluster of Differentiation 4 (CD4) count. HIV targets CD4 cells, therefore, these cells are integral to the immune response as they are an index of the effects of HIV on immune functioning. Cognitive-behavioral and problem-solving strategies adapted from Life-Steps Intervention (Safren, 2008) were utilized in this intervention to increase adherence. These strategies examine behaviors and obstacles that may impede an individual’s adherence, such as feelings of worthlessness and experiences of HIV stigma. These barriers are reduced by teaching youth to understand the linkages of thoughts, feelings and behaviors, and how to shift thinking to alter mood and behavior. The strategies also identify targets for wellness and improved mood. Positive factors are enhanced through behavioral coping strategies that counter negative mood (e.g., participating in an activity that expends energy). Additionally, the treatment includes skills in cognitive restructuring and catching negative automatic thoughts.

Skills and strategies contributing to wellness occur throughout the intervention. The goal of treatment is not only to equip participants with skills and tools to decrease depressive symptoms, but to enhance wellness and overall quality of life. Wellness is presented as a continuum that can fluctuate over time instead of a “well” or “not well” concept. Specifically, six general areas of wellness are explored. These main areas include: self-acceptance, social, success, self-goals, spiritual, and soothing (adapted from Ryff & Singer, 1996; Ryff, 1996). The concept of wellness, described by Ryff and Singer (1996) include aspects of self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. The manual utilizes the core of these concepts of wellness, specifically ones that are salient to youth with HIV (Macdonell, Naar-King, Murphy, Parsons, & Huszti, 2011). Additionally, to further tailor the manual to this particular population, the family component of the treatment was implemented in a flexible manner. Participants were provided the opportunity to include their family, significant others or no family (if the youth were emancipated) in the treatment sessions.

Stages of treatment and structure of sessions

A manual was developed to aid therapists and guide them through the H&W CBT treatment intervention. The H&W CBT treatment consists of three stages, which include 14 planned sessions over a six-month period, as well as additional sessions for crisis intervention or attrition prevention as needed. The manual can be flexibly tailored to fit individual needs if a participant needs fewer than the planned sessions. Initially, participants meet with the therapist at the baseline visit for a treatment overview. The intervention is scheduled weekly for the first 8 weeks, biweekly for 2 months, and monthly until the end of the intervention, for a total of 6 months of treatment. Participants also received psychotropic medication management at baseline and every two weeks through week 12 (weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12), and then monthly through week 24 (weeks 16, 20 and 24). Medication management followed a treatment algorithm in which patients could receive no medication or treatment with medication on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI ; Stage 1), treatment with a different SSRI (Stage 2), or treatment with a non-SSRI (Stage 3; Emslie, Croarkin, Mayes, 2012). H&W CBT sessions lasted on average 60 minutes and medication management (MM) sessions lasted approximately 30 minutes. All participants were compensated for their time, compensation was site-specific and ranged from thirty to fifty dollars per treatment visit.

The H&W CBT manual is intended to be used in a flexible manner. It provides the therapist with guidelines to use for content and session structure (see Table 1); however, the therapist can modify a session based on his/her clinical judgment as long as the overall approach is consistent with the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy. The treatment is focused on the patient’s needs and should be used as a guideline rather than a rigid procedure. For example, if a participant struggles with withdrawal from family and peers, the therapist has the flexibility to address behavioral coping skills in additional sessions. Supplemental sessions are included in the manual and may be used at any point throughout treatment to address specific concerns of either the participant or therapist. The supplements are designed to assist the therapist in applying core skills to common issues such as anxiety, hopelessness, and sleep hygiene, assertiveness, emotional regulation, impulsivity, interpersonal conflict, social support, irritability, self-esteem, and social skills.

Table 1.

CBT Treatment Overview

| Treatment Stage |

Objective | Session # | Session Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Psychoeducation and Motivation for Treatment | 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

||

| Stage 2 | Reducing Symptoms | 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

||

| 5 |

|

||

| 6 |

|

||

| 7 |

|

||

| 8 |

|

||

| Stage 3 | Achieving and Maintaining Wellness | 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

||

| 11 |

|

||

| 12 |

|

||

| 13 |

|

||

| Continuation | Consolidation of Treatment Gains | 14 |

|

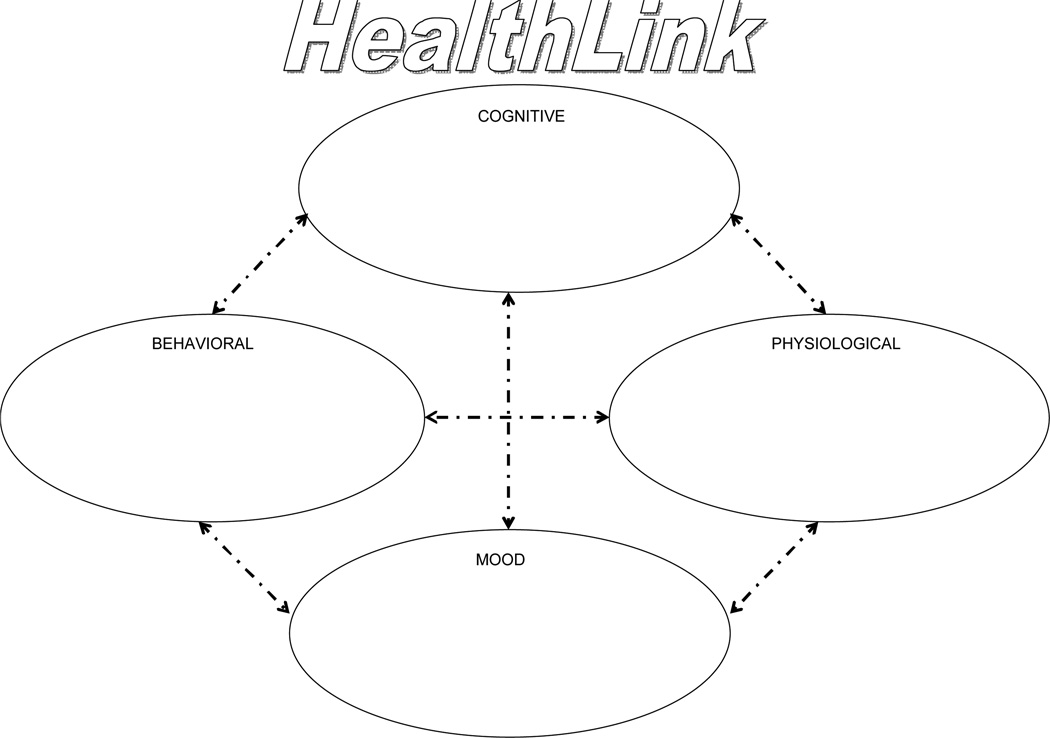

Stage 1 of the H&W CBT treatment (sessions 1 and 2) focuses on engaging the participant (and family members as appropriate) in the treatment. Psychoeducation is provided on the co-occurrence of depressive illness and HIV infection, as well as treatment options for depression in this population. Rapport building, an explanation of the CBT model of treatment for depression, and goal setting are emphasized. In addition to mitigating depressive symptoms and increasing HIV treatment adherence, participants could choose specific goals such as reducing interpersonal conflict or managing anxiety. Motivational interviewing strategies are also utilized in Stage 1 to help the participant identify the discrepancy between their current lifestyle and goals for treatment. This includes adherence goals and training (Safren, 2008). The participant is introduced to HealthLink (See Figure 1), which serves as a framework to individualize, plan, organize, and integrate the treatment. The figure is used to help the participant to identify the relationships between mood, behavior, thoughts and physiological symptoms related to living with HIV. Throughout treatment, the participant continues to add skills, build strengths and identify triggers to negative emotional reactions.

Figure 1.

HealthLink serves as a framework to individualize, plan, organize, and integrate the treatment.

Stage 2 (sessions 3 to 8) emphasizes reduction in symptoms by teaching the participant core CBT skills, which target any remaining depressive symptoms. These skills most commonly include mood monitoring, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, core beliefs, and problem solving. Based on common problems among depressed participants, supplemental sessions include: training in emotional regulation, social skills, assertiveness, and relaxation.

The goal of Stage 3 (sessions 9 – 13) is achieving and maintaining wellness by focusing on wellness strategies and lifestyle changes designed to enhance strengths and extend recovery. Once the depressive symptoms begin to remit, the participant explores strategies that promote health and well-being, such as mastery, positive self-regard, goal setting, quality relationships, and optimism (Jaycox, 1994; Ryff, 1996). Finally, the Continuation Stage (Session 14) emphasizes the consolidation of treatment gains. The content of the last stage varies depending on the participants’ needs.

Methods

Participants

In order to be included in the study, participants were required to be ages 16 −24 years, engaged in care at the participating Adolescent Medicine Trials Unit (AMTU), have documented HIV by medical records, and have a diagnosis of nonpsychotic depression, either Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Depression NOS, or Dysthymia as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Participants were exclude from the study if they had a history of any psychotic disorders or Bipolar I or II Disorder, had a fist degree relative diagnosed with Bipolar I Disorder, had a diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependence according to DSM-IV in the last 6 months, and if they were at imminent danger to themselves or others.

To test the CBT intervention, we conducted an initial feasibility study with 8 participants, 16–24 years of age (M= 21.5, SD= 2.1), diagnosed with HIV and who also had a DSM-IV diagnosis of either Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Dysthymia or Depression Not Otherwise Specified as determined by a licensed mental health clinician. One participant had a comorbid diagnosis of Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder inattentive type. The clinical evaluation to determine DSM-IV diagnoses was done per clinic standard of care for each site. Participants were mostly male (87%; 7 males, 1 female) and Non-Hispanic, Black/African-American (87%). Six of the 8 participants were Men who have Sex with Men (MSM), and were behaviorally infected. One participant was infected though high risk heterosexual contact, and one participant was perinatally infected. All but two participants were on antiretroviral medication treatment.

Measures

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician (QIDS-C: Bernstein, 2010) was used to evaluate depression severity, a primary outcome for this study. This scale was administered by a licensed medical or mental health clinician at baseline and every MM visit (weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20 and 24) to assess depressive symptoms. The total score ranges from 0 to 27. QIDS-C depression severity thresholds were empirically derived and have been categorized as 6 to 10 for mild, 11 to 15 for moderate, 16 to 20 for severe, and 21+ for very severe depression. The QIDS-C has highly acceptable psychometric properties including high internal consistency and high concurrent validity with previously established measures. It is also a sensitive measure of change in depressive symptom severity associated with effective treatment (Trivedi et al., 2004).

Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS: Young & Beck, 1980) was used to rate therapists’ conduct of the CBT sessions. This is a scale developed to measure therapist competency in and adherence to the cognitive behavioral model of treatment. The items are rated on a scale from 0 (poor) to 6 (excellent), with a 4 being the standard for an acceptable level of competence on each item. This scale was used by the CBT supervisor to rate audio recordings of the CBT sessions.

Session Evaluation Form (SEF; Harper, 2003) was used to evaluate therapists’ and clients’ evaluation of each of the CBT sessions. These evaluations were used in the initial phase of the study in order to formally assess each module and to determine if there were any modifications needed to the manual. The evaluations were used by the authors to finalize the treatment manual for further use. The SEF is a brief 13-item self-administered questionnaire. The SEF consists of ten items on a four-point response scale (ranges 1, strongly disagree, to 4, strongly agree) aimed at gathering information about the participant’s experience with the session (i.e., the session was relevant to their life, will be able to apply what was learned; see Table 2). Additionally, there are 3 open-ended items eliciting information about which aspects of the session were the most and least useful, as well as an opportunity to state potential changes. The SEF has been adapted for use by therapists and includes areas to indicate participant response, relevance, and areas for improvement.

Table 2.

Participant Session Evaluation Form (SEF) Results

| Q1. I learned a lot from this session. | ||

| Q2. I will be able to apply what I learned from this session in my life. | ||

| Q3. I was given an opportunity to participate and discuss information. | ||

| Q4. The session was well organized. | ||

| Q5. The topic of this session was interesting. | ||

| Q6. The therapist stimulated my interest in the material. | ||

| Q7. The topic of this session was relevant to my life. | ||

| Q8. The session was enjoyable. | ||

| Q9. I would recommend this session to others. | ||

| Q10. I felt comfortable participating in this session. | ||

| Weeka | Participants |

Mean Satisfaction M(SD) |

| 1 | N=8 | 3.88(±.13) |

| 2 | N=8 | 3.83(±.15) |

| 3 | N=8 | 3.76(±.15) |

| 4 | N=8 | 3.88(±.16) |

| 5 | N=7 | 3.86(±.00) |

| 6 | N=8 | 4.00(±.00) |

| 7 | N=8 | 3.66 (±.12) |

| 8 | N=7 | 3.66(±.10) |

| 10 | N=7 | 3.84(±.05) |

| 12 | N=8 | 4.00(±.00) |

| 14 | N=7 | 3.86(±.00) |

| 16 | N=8 | 3.88(±.00) |

| 20 | N=8 | 3.88(±.00) |

| 24 | N=8 | 3.88(±.00) |

Note. a Excludes extra visit sessions.

Response for each of the 10 items was converted to a 4-point likert scale (4=Strongly Agree; 3=Agree; 2=Disagree; 1=Strongly Disagree). The satisfaction score was the mean response given by participants on each of the 10 items.

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) (Nguyen, Attkisson, & Stegner, 1983),used to evaluate clients’ overall satisfaction with the CBT intervention, was administered at the end of treatment. This scale has a range of 1–4, with 4 representing high satisfaction.

Procedures

The larger study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to test a novel behavioral intervention to treat depression in HIV positive adolescents and young adults. Four sites were assigned to either the H&W CBT and MM (COMB) group or the Treatment As Usual (TAU) group. Participants enrolled at COMB sites received a 24-week intervention consisting of Medication Management visits and CBT visits to treat depression. The COMB group involved pilot testing of H&W CBT and MM manuals, and the participants and clinicians provided feedback to aid in revision of the manuals. Study coordinators and site clinicians documented depression symptoms and treatment regimens for all participants for 24 weeks on QIDS as well as satisfaction with treatment surveys.

We present the data from the open trial of the participants in the COMB condition. The larger RCT is still in progress. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating organizations.

H & W CBT

Each enrolling site participating in the COMB intervention included a site clinician who prescribed medication and a site therapist who performed H&W CBT. All therapists were either at the master’s level or doctoral level of training. Therapists had extensive training and exposure to CBT prior to the current study. Additionally, some therapists had training in protocol based CBT. The CBT therapists received on-site, two day intervention training (e.g. didactic instruction, role plays, and vignettes) and participated in weekly monitoring and supervision calls for the H&W CBT. CBT sessions were digitally recorded for quality control. Forty percent of all the recorded sessions were rated by the CBT supervisor using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS; Young & Beck, 1980) with 95% rated as of acceptable quality.

Medication Management

Medication management was done by site clinicians and followed a manual that was developed based on existing practice guidelines for treating adolescent depression, as well as recommendations from APA guidelines for treating depression in patients with HIV. The algorithm in the manual was adapted from the algorithm used in a completed trial of adolescent suicide attempters (Brent et al., 2009). The manual was specifically modified to address issues specific to those living with HIV, including taking into account drug interactions. Clinicians overseeing psychotropic medications participated in bi-weekly calls for the MM component of treatment.

All 8 participants entered the study currently on no antidepressant medication. During the course of the trial, 75% (n=6) of the participants started treatment with antidepressant medication. Most (n=5) initiated treatment on Stage 1 (SSRI); one entered at Stage 3 (non-SSRI), with the medication selection (bupropion) based on need for treatment of both depression and significant attention difficulties. Only 2 participants were also prescribed adjunct medication for associated symptoms (1 with trazodone for sleep, 1 with aripiprizole for irritability).

Results

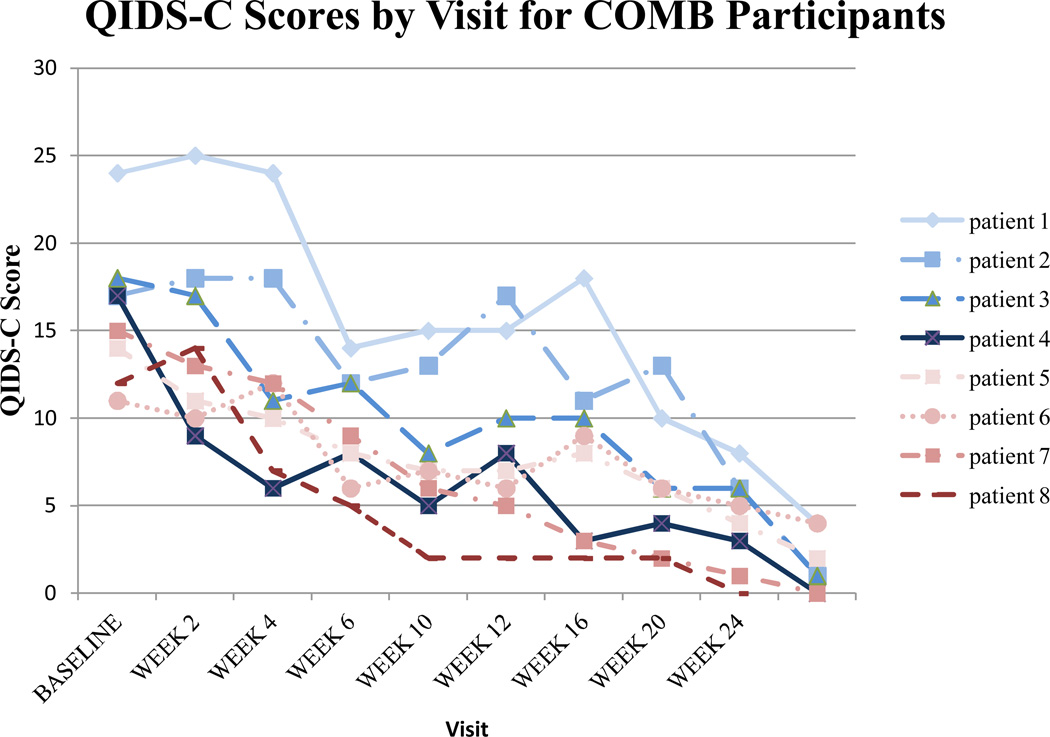

Depression Severity

On the QIDS-C, the mean of the 8 participants at baseline was 16, with scores ranging from 12 to 24. The mean score at week 24 was 1.5, with scores ranging from 0–4. By the end of treatment, all participants had scores that met criteria for remission (QIDS-C ≤ 5). Figure 2 shows the QIDS-C scores by week for each participant.

Figure 2.

QIDS-C scores by week for each participant.

Adherence Levels

Adherence levels to antiretroviral medication were self-reported by participants at baseline, week 6, 12, and 24. Percent adherence was calculated by number of medications prescribed minus the number missed, divided by number of medication prescribed over the past week. Mean percentages for those on ARV (n = 5 at baseline, n = 6 at weeks 6, 12, 24) were as follows: 74.3% (SD = 25.6) at baseline; 66.7% (SD = 42.1) at week 6; 69.0% (SD = 43.7%) at week 12; 90.5% (SD = 11.7) at week 24.

Participants’ Satisfaction

Preliminary findings from the SEF indicate that the participants responded to the sessions positively. Participants most frequently strongly agreed or agreed on the SEF questions (see Table 2 for average satisfaction ratings per week). The overall average response on an item across all sessions was a 3.85 out of a possible 4. Additionally, the open-ended items elicited mainly positive feedback in regard to session content (e.g., “I loved the fact that I was able to challenge negative thoughts into positive ones”; “I found that self-esteem is what everyone needs in order to allow themselves to feel comfortable in different situations”). Participants had minimal to no feedback regarding change in session content. Of note is that the ratings tended to be slightly lower in those sessions that were less structured and focused on skill review.

We found high ratings of consumer satisfaction for the overall intervention on the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire – 8 (CSQ-8) (Nguyen et al., 1983). Across all items, the average score was a 3.94 (SD = .12) indicating very high levels of satisfaction. See Table 3 for a comprehensive breakdown of scores.

Table 3.

Item-Specific Frequencies and Summary Scores for Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) among Eight COMB Participants at Week 24

| COMB Participants |

|

|---|---|

| Item-Specific Frequencies | |

| How would you rate the quality of service you have received | |

| Excellent | 8 (100.0) |

| Did you get the kind of service you wanted | |

| Yes, generally | 1 (12.5) |

| Yes, definitely | 7 (87.5) |

| To what extent has our program met your needs | |

| Most of my needs have been met | 1 (12.5) |

| Almost all of my needs have been met | 7 (87.5) |

| If a friend were in need of similar help, would you recommend our program to him or her | |

| Yes, definitely | 8 (100.0) |

| How satisfied are you with the amount of help you have received | |

| Very satisfied | 8 (100.0) |

| Have the services you received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems | |

| Yes, they helped | 1 (12.5) |

| Yes, they helped a great deal | 7 (87.5) |

| In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the service you have received | |

| Mostly satisfied | 1 (12.5) |

| Very satisfied | 7 (87.5) |

| If you were to seek help again, would you come back to our program | |

| Yes, definitely | 8 (100.0) |

Therapists’ Satisfaction

The scores from the SEF indicated favorable responses from the therapists for each of the sessions. Therapists reported many of the concepts and corresponding worksheets to be helpful (e.g., “check, challenge, change: he sees the importance of challenging these negative thoughts”). Therapists were also able to provide feedback about reducing content, moving content, and suggestions for restructuring worksheets. Overall, therapists found the session content to be applicable and helpful to the participants. A summary of the therapist’s SEF scores is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Therapist Session Evaluation Form (SEF) Results

| Q1. The participant learned a lot from this session. | ||

| Q2. The participant will be able to apply what he/she learned from this session in his/her life. | ||

| Q3. The participant was given an opportunity to participate and discuss information. | ||

| Q4. The session was well organized. | ||

| Q5. The topic of this session was interesting. | ||

| Q6. I was able to stimulate the participant’s interest in the material. | ||

| Q7. The topic of this session was relevant to the participant’s life. | ||

| Q8. The session was enjoyable for the participant. | ||

| Q9. I would recommend this session to others. | ||

| Q10. The participant felt comfortable participating in this session. | ||

| Weeka | Therapistsb |

Mean Satisfaction M(SD) |

| 1 | N=8 | 3.45(±.06) |

| 2 | N=8 | 3.14(±.14) |

| 3 | N=8 | 3.43(±.09) |

| 4 | N=8 | 3.52(±.14) |

| 5 | N=7 | 3.36(±.19) |

| 6 | N=8 | 3.43(±.13) |

| 7 | N=8 | 3.28(±.16) |

| 8 | N=7 | 3.47(±.27) |

| 10 | N=7 | 3.33(±.07) |

| 12 | N=8 | 3.30(±.13) |

| 14 | N=7 | 3.37(±.19) |

| 16 | N=8 | 3.31(±.15) |

| 20 | N=8 | 3.30(±.20) |

| 24 | N=8 | 3.43(±.12) |

Note. aExcludes extra visit sessions.

Therapists had the option to mark ‘don’t know’ for some questions; that response was excluded when calculating the mean satisfaction scores.

H&W CBT Case Illustration

Identifying details in this case vignette have been modified to protect the participant’s confidentiality.

Martin is a 26 year old African American male who identifies as gay. He acquired HIV through consensual sexual contact when he was 24 years old. He began the pilot program with a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder, Moderate, Recurrent over the last 10 years. Martin did not have any comorbid diagnoses. At baseline his QIDS score was a 14, indicating moderate depression. He was not on anti-depressant medication at the beginning of treatment; however, he was treated with an SSRI at week 16, as he was still endorsing depression symptoms. He was treated with medication for one week, but he chose to discontinue due to side effects. He endorsed multiple depression symptoms including irritable mood, decreased interest in activities, sleep disturbance, excessive fatigue, decreased appetite, feelings of worthlessness, thoughts of suicide and low self-esteem. Martin described a history of suicidal ideation, intent and planning, although he had no history of suicidal behavior. Martin began his highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen 10 months prior to beginning the H & W CBT and had a CD4 over 800 and a viral load below detection.

Although he was adherent to his medication regimen, Martin struggled with negative mood and interpersonal and family conflict. Negative automatic thoughts that were salient to Martin included: “If I tell people I have HIV, they will judge me” and “It’s my fault that people in my home are unhappy.” Specific focus on HIV for this patient was on managing negative thoughts related to stigma associated with HIV infection. Martin’s negative thinking pattern reinforced his depressive symptoms and hindered his healthy coping strategies. The therapist used strategies to help Martin reframe his negative thoughts, including challenging his unhelpful thinking and generating Positive Self Statements with the aim to increase his self-esteem and self-worth. An example of an alternative, helpful thought includes, “Other people have illnesses and I don’t judge them; I am a person with HIV which does not define me; There are other parts of my life that are bigger than the HIV illness piece.” Through role play interactions he gained communication strategies for reducing interpersonal conflict. Often this role play included the therapist playing the role of the family member, and Martin using assertive language to communicate his reactions to the family member and to articulate his needs to them. Martin was able to let his family know not only what he experienced as hurtful language, but what types of support he needed to improve his mood and quality of life.

Martin previously engaged in habitual marijuana use. Throughout the treatment, he identified his marijuana use as an unhelpful coping strategy and using the Wellness Plan learned new strategies, including relaxation techniques and behavioral coping. Martin and the therapist collaborated on a Relapse Prevention and Wellness Plan that included the following components.

For when he experiences depressed or irritable mood and thoughts of worthlessness, the Plan calls for him to engage in exercise, getting social support, and positive self-talk. Sleep disturbance and fatigue require him to use exercise, as well as maintain a sleep schedule and using relaxation techniques (deep breathing and guided imagery). Future suicidal thinking is addressed in the plan using a hierarchical safety plan, with early steps including use of distraction and behavioral coping skills, and progressing to getting with friends for social support, to finally letting identified close friends, family and / or professionals know of his suicidal thoughts and urges.

Martin is no longer using marijuana to cope with life challenges. He continues to use deep breathing, muscle relaxation and positive self-statements when he feels depressed. His communications skills have significantly improved, in that he reminds his family when they make negative comments, versus just ‘letting it go’, but experiencing distress. Martin finds that communicating his feelings more directly helps him feel empowered.

At the end of the six months, his QIDS score was a 2, indicating full remission of his depression. He could discriminate between the prior coping strategies and his current ones. For example, in a workbook exercise he determined how his Old Me (negative thoughts, emotions and unhelpful coping strategies prior to treatment) and his New Me (self talk strategies and positive coping skills) were different even amidst similar circumstances.

At 15 months post-intervention and with no additional counseling support, Martin has maintained the gains he made during the program. He continues to be compliant with his medication treatment for HIV and utilizes deep breathing, guided imagery and behavioral coping strategies when facing difficult situations. Following the intervention, Martin completed a training program in the health professions and obtained employment. He is currently living with a family member and has transitioned his HIV care to an adult medical clinic.

Conclusions

It has been shown that young individuals living with HIV have an increased risk for depression and that depression can negatively affect medication adherence and wellness. The results from this feasibility trial show that the H&W CBT intervention, along with tailored MM, treatment was acceptable to both patients and therapists. Additionally, the skills employed in H& W CBT seem to be effective in this population to manage depressive symptoms in the context of a chronic illness. All patients treated in this feasibility trial reached remission and demonstrated improved adherence. Thus, incorporating traditional CBT strategies with a wellness perspective may not only improve depressive symptoms, but also promote disease management. These preliminary findings are consistent with the results from adult trials using CBT with HIV infected individuals with improvement on depression and adherence outcomes. (Safren et al., 2009; Safren et al., 2012).

Limitations

These results should be tempered by an awareness that this was an open trial, without a control comparison condition and, thus, the efficacy of this intervention has yet to be established. The scope of this paper was specifically to focus on the development and pilot testing of the H&W CBT intervention, thus we did not compare the COMB group to the TAU group. While the intervention is acceptable and feasible, a randomized controlled study is needed to confirm the efficacy of H & W CBT.

Clinical Implications

Based on the literature and our preliminary findings using a cognitive behavioral approach, with a special focus on issues of adherence and illness management, is an intervention strategy that should be considered in the treatment of youth with depression and HIV. In addition, MI strategies should also be considered for engaging individuals in treatment and fostering adherence to medical regimens. Specifically, skills which promote wellness and prevent relapse of depressive symptoms appear to be helpful in this population. Overall, H&W CBT and MM intervention may be a promising treatment option for adolescents living with HIV and depression.

Future Directions

The treatment developed from this open pilot (H & W CBT) will be part of a larger, Phase 2 randomized controlled trial, comparing this combination strategy (H & W CBT and MM) to treatment as usual. Data from this trial will allow us to determine the efficacy of this treatment in youth with depression and HIV. If proven effective, these strategies, can be applied to other medical populations with comorbid depression.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) from the National Institutes of Health (U01 HD 040533 and U01 HD 040474) through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (B. Kapogiannis, C. Worrell) with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse and Mental Health. ATN sites 01 - University of South Florida and 04 – The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia participated in the study from which the manuscript evolved. The study was scientifically reviewed by the ATN’s Behavioral Leadership Group; The ATN Coordinating Center for Network scientific and logistical support (C. Wison and C. Partlow); The ATN Data and Operations Center at Westat (J. Korelitz and B. Driver); The ATN Community Advisory Board and the youth who participated in the study. We wish to thank Dr. Steven Safran for consultation on the development on the treatment manual.

References

- Bernstein IH, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Psychometric Properties of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology in Adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(4):185–194. doi: 10.1002/mpr.321. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing BE, Burman MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, Turner BJ, Eggan F, Beckman R, Vitiello B, Morton SC, Orlando M, Bozzette SA, Ortiz-Barron L, Shapiro M. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Issues TWGoQ, Staff A. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Depressive Disorder. [practice parameters] Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):24. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Greenhill LL, Compton S, Emslie G, Wells K, Walkup JT, Turner JB. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters study (TASA): predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein-Klomek A, Zalsman G, Mufson L. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT-A) Israel Journal of Psychiatry & Related Sciences. 2007;44(1):40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein REK, Group TG-PS. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and Ongoing Management [guideline] Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton SN, March JS, Brent DA, Albano AM, Weersing VR, Curry JF. Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy for Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents: An Evidence-Based Medicine Review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):930–959. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Croarkin P, Mayes TL. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS (ATN 080) Medication Management Manual, Version 2.0. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando SJ. Psychopharmacologic treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11(3):235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LB, Towner WJ, Klein DB, Bersoff-Matcha S, Weinberg WG, Antoniskis D, Mogyoros M, Dodge WT, Dobrinich R, Quesenberry CP, Kovach DA. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(3):348–390. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d53e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Reivich KJ, Gillham J, Seligman ME. Prevention of depressive symptoms in school children. Behavior Research & Therapy. 1994;32:801–816. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennard B, Hayley C, Hughes J, Jones J, Hines T. CBT Treatment Manual for ATN 080. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Macdonell KE, Naar-King S, Murphy DA, Parsons JT, Huszti H. Situational temptation for HIV medication adherence in high-risk youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(1):47–52. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malee K, Williams P, Montepiedra G, McCabe M, Nichols S, Sirois PA, Storm D, Farley J, Kammerer, & the PACTG219C Team Medication adherence in children and adolescent with HIV infection: Associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25:191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Belzer M, Durako SJ, Sarr M, Wilson CM, Muenz LR, Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:764–770. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Templin T, Wright K, Frey M, Parsons JT, Lam P. Psychosocial Factors and Medication Adherence in HIV-Positive Youth. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20(1):44–47. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6(3–4):299–313. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. Psychological well-being: Meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics. 1996;65:14–23. doi: 10.1159/000289026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Soroudi N. Coping with Chronic Illness: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach for Adherence and Depression. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Mayer KC. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(3):404–415. doi: 10.1037/a0028208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C, Wolff J, Uhl K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression and suicidality. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(2):191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team TT, March JS. Fluoxetine, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, and Their Combination for Adolescents with Depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(7):807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, Crismon K, Shores-Wilson Troprac EB, Dennehy B, Witte B, Kashner TM. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Ratings (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of Psychotherappy for Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]