Abstract

BACKGROUND

The utilization of post-mastectomy reconstruction varies with socioeconomic status, but the etiology of these variations is not understood. We investigate whether these differences reflect variations in the rate and/or qualitative aspects of the provider’s discussion of reconstruction as an option.

STUDY DESIGN

Data were collected via chart review and patient survey for Stage I - III breast cancer patients during the National Initiative on Cancer Care Quality. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify predictors of reconstruction and discussion of reconstruction as an option. Predictors of not receiving reconstruction despite a documented discussion were also determined.

RESULTS

253 of 626 patients received reconstruction (40.4%). Younger, more educated, white women who were not overweight or receiving post-mastectomy radiation were more likely to receive reconstruction. Patients who were younger, more educated, and not receiving post-mastectomy radiation were more likely to have a discussion of reconstruction documented. If a discussion was documented, patients who were older, Hispanic, not born in the U.S., and women who received post-mastectomy radiation were less likely to receive reconstruction. The greatest predictor of reconstruction was medical record documentation of a discussion about reconstruction.

CONCLUSIONS

We observed disparities in the likelihood of reconstruction, which are at least partially explained by differences in the likelihood that reconstruction was discussed. However, there are also differences in the likelihood of reconstruction based on age, race, and radiation once discussions occurred. Efforts to increase and improve discussions regarding reconstruction may decrease disparities for this procedure.

INTRODUCTION

Post-mastectomy breast reconstruction is an elective, costly procedure, but an important component of the surgical care of breast cancer patients. As with many other high-cost elective procedures, previous studies have demonstrated racial and socioeconomic variations in the utilization of post-mastectomy reconstruction.1–10 Careful review of these studies suggests that the observed racial disparities likely reflect differences in socioeconomic status. In fact, the majority of studies that account for differences in individual SES find that race is not a significant predictor of reconstruction. The association between socioeconomic characteristics, such as income, education, and employment status, and rates of reconstruction are larger and more consistent. The underlying etiology of these socioeconomic variations has not been elucidated. Possible contributors include differences in access to care, clinical factors, patient preference or provider bias.

Previous work using data from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network suggests that factors such as provider bias and patient preference are associated with differences in the use of breast reconstruction, even amongst patients with similar access to care.7 In that study, patients receiving mastectomy at one of eight high-volume U.S. comprehensive cancer centers still exhibited disparities in rates of reconstruction explained in part by factors such as income, education, employment and insurance status.

Clinical factors, such as stage, co-morbidities, and the use of post-mastectomy radiation, should play a role in decision making about reconstruction, which must weigh the advantages of reconstruction against the operative risk. Beyond clinical factors, as a purely elective procedure, the decision to receive reconstruction should ultimately reside with the individual patient in keeping with her values and preferences.11, 12 An individual’s attitudes and preferences regarding healthcare result from life experiences, which are often influenced by the socioeconomic conditions in which that person exists. 13–15 Decisions regarding elective procedures such as reconstruction can therefore systematically vary according to socioeconomic status (SES). For particular individuals, concerns about cost, prolonged time off from work and the potential need for secondary procedures can also weigh into the decision.16 However, regardless of what factors are salient, patients cannot meaningfully participate in the decision-making process without an informative discussion of reconstruction that enables them to understand and weigh the risks and benefits.

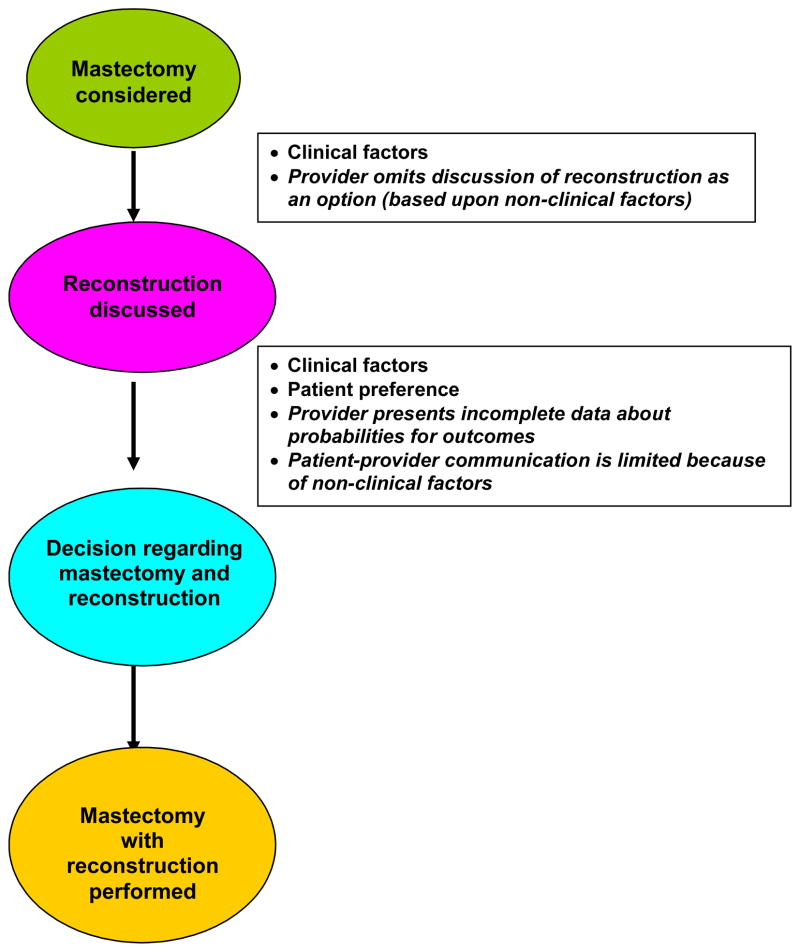

Provider bias may contribute to the observed socioeconomic differences in at least two ways. First, amongst patients without clinical contraindications, providers can decide whether or not to discuss the option of reconstruction based on race or socioeconomic characteristics. Second, even if providers choose to discuss the option of reconstruction, the content of those discussions may vary due to cultural, educational or language barriers between patient and provider or due to differences in the provider’s presentation of the risk/benefit ratio associated with the procedure. Studies suggest that patient perception of the surgeon’s preference plays a major role in patient decision-making regarding breast surgery.17, 18 We also know that there are racial and ethnic variations in physician-patient communication and in patient perceptions of the quality of their communication with physicians.19–22 Figure 1 illustrates how clinical factors, patient preference, provider bias in discussing reconstruction, and qualitative aspects of communication can contribute to whether or not a patient receives reconstruction. Understanding the role of each of these phenomena in the decision-making process is crucial in designing interventions to alleviate disparities in rates of reconstruction.

Figure 1. Schema depicting the factors that potentially contribute to whether a patient receives reconstruction following mastectomy.

Patients cannot meaningfully participate in decision-making without an informative discussion of reconstruction as an option. Once mastectomy is considered as a surgical option, reconstruction should be discussed. This discussion may or many not take place based on clinical factors; however, the may also omit the discussion due to bias based on non-clinical factors. Once the discussion is initiated, there are a number of factors that determine whether a decision is made to proceed with the mastectomy with or without reconstruction. These relate to clinical factors, patient preferences, provider preferences and how these are communicated to the patient. The provider may present incomplete data about probabilities for outcomes with as compared to without reconstruction. Patient-provider communication could be limited because of non-clinical factors (e.g., limited visit time, limited English proficiency, etc.). The factors in italics represent potential target areas to decrease disparities.

METHODS

Identification of Cohort

Data were collected as part of a larger study, the National Initiative on Cancer Care Quality (NICCQ). The methodology for this study is reported in detail elsewhere.23, 24

Patients were eligible for the larger study if their first diagnosis of stage I–III breast cancer occurred during 1998 and they were registered by an American College of Surgeons (ACoS)-approved hospital cancer registry located in one of five Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs): Atlanta, Cleveland, Houston, Kansas City, and Los Angeles. Participants were limited to females, 21 to 80 years of age at diagnosis, who were English-speaking, and alive when contacted to participate in this study approximately four years after diagnosis. To be eligible for this analysis, participants must have received a mastectomy as definitive treatment for their incident breast cancer.

The NICCQ research team recruited a probability sample of ACoS-approved hospital cancer registries in Los Angeles and all available registries in the other four MSAs. Using ACoS National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) data, 3,194 patients with an initial diagnosis of breast cancer during 1998 were identified. After excluding 290 patients known to be deceased and 296 for whom either the doctor refused contact, the patient was out of country, or no valid contact address was available, 2608 women were confirmed to be alive. Of these women, 1690 (65%) completed the survey and 1287 (76%) of the survey respondents also had complete medical record abstraction. Of these, 626 had mastectomy and define the analytic cohort for this report.

Data Collection

Each patient completed an 18-page survey four years after diagnosis, provided consent for medical record abstraction, and submitted a listing of all providers seen since diagnosis. The NICCQ research team requested photocopies of consenting patients’ ambulatory medical records from all cancer providers and primary care physicians. When abstraction revealed cancer providers not reported by the patients, those physicians’ medical records were requested and abstracted. Twelve trained nurses abstracted all available records using a computer-based medical record abstraction instrument. Data obtained from the medical record included detailed information about tumor characteristics, staging, estrogen and progesterone receptor status, referrals and decision-making, initial cancer treatment, adjunctive medications, and comorbid conditions. We used medical record data to define mastectomy. Some variables were collected from both survey and MR abstraction. An algorithm was designed for each variable based on the reliability of the method of data collection.

Data Analysis

Rates of reconstruction and documented discussion of the option of reconstruction were calculated for the cohort. Univariate analysis was used to investigate predictors of reconstruction including: clinical characteristics (age, comorbidities, and body mass index (BMI)), socioeconomic status (employment, education, race, primary language, country of birth, and insurance status), disease stage, and treatment (use of chemotherapy or radiation therapy). The number of patients receiving reconstruction was calculated for each categorical variable and compared using the Mantel-Haenszel test for trend or chi-square test as appropriate. Age and BMI were treated as continuous variables. The mean was calculated for patients receiving and not receiving reconstruction and a t-test was used for significance testing. Results for the univariate analysis are presented in categories, but the reported p-value as based on the continuous variable. All estimates and tests were weighted to account for hospital and patient non-response.23 For the univariate analysis, significance was set at 0.10. A similar univariate analysis was performed with the same covariates for the following three other outcomes: (1) documentation of a discussion of reconstruction; (2) reconstruction given documentation of a discussion; and (3) reconstruction without documentation of a discussion

We used multivariable logistic regression to investigate predictors that were found to be significant in the univariate analysis. Missing data ranged from 0.3% – 2.4% for individual variables. Since these numbers were small, patients with missing variables were excluded from the multivariable models. Multivariable results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All estimates and tests are again weighted to account for hospital and patient non-response.23 Sample survey logistic regression was used to account for stratification according to SEER MSA and clustering within hospitals. All potential interaction terms were tested for inclusion in the model. For the multivariable models, significance was set at 0.05. Because this analysis was exploratory, we did not adjust the type 1 error rate to account for multiple comparisons; thus, p-values should be interpreted cautiously. The number of significant associations (p<0.05) in these analyses is much greater than expected by chance if there were no associations in the data. SAS 9.1 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Of 626 patients undergoing mastectomy as definitive treatment for Stage I, II or III breast cancer in the NICCQ database, 253 (40.4%) received reconstruction. Medical records documented the occurrence of a discussion regarding reconstruction in 249 (39.8%) of 626 patients.

Table 1 shows the unadjusted associations between the socioeconomic and race variables and whether discussion of reconstruction was documented in the chart. Reconstruction was discussed less frequently with older, less educated and uninsured patients. The prevalence of discussion regarding reconstruction was also lower for patients who did not work full-time and spoke a primary language other than English. Clinical and disease-specific variables that were found to be significant on univariate analysis include: chemotherapy use (p = 0.004), XRT (p = 0.02), body mass index (p = 0.04), AJCC stage (p = 0.01). Neither the presence of comorbidities nor lymph node involvement was associated with documentation of a discussion regarding reconstruction on univariate analysis.

Table 1.

Documentation of Discussion Regarding Reconstruction

| Variable | n* | Documented discussion of reconstruction, n (%)† | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, y | |||

| 25–34 | 10 | 3 (30) | <0.0001‡ |

| 35–44 | 37 | 19 (51) | |

| 45–54 | 169 | 74 (44) | |

| 55–64 | 150 | 73 (49) | |

| 65–74 | 155 | 45 (29) | |

| 75+ | 105 | 15 (14) | |

|

| |||

| Born in US | |||

| No | 80 | 28 (35) | 0.74 |

| Yes | 546 | 201 (37) | |

|

| |||

| Primary Language | |||

| English | 562 | 38 | 0.007 |

| Other | 42 | 18 | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| African American | 50 | 13 (27) | 0.13§ |

| Asian | 22 | 11 (51) | |

| Hispanic | 63 | 20 (32) | |

| Caucasian | 523 | 198 (38) | |

|

| |||

| Any Insurance | |||

| Yes | 603 | 226 (38) | 0.015 |

| No | 23 | 3 (12) | |

|

| |||

| Employment | |||

| Full-time | 270 | 119 (44) | 0.0005 |

| Part-time | 72 | 25 (35) | |

| Not working | 281 | 84 (30) | |

|

| |||

| Educational Level | |||

| < 8th grade | 40 | 4 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Some HS | 28 | 6 (20) | |

| HS grad/GED | 163 | 51 (32) | |

| Some college | 214 | 84 (39) | |

| College grad | 83 | 43 (52) | |

| > College grad | 87 | 36 (41) | |

|

| |||

| Radiation | |||

| Yes | 234 | 69 (30) | 0.023 |

| No | 392 | 160 (41) | |

|

| |||

| Co-mordities | |||

| Yes | 243 | 87 (36) | 0.69 |

| No | 383 | 143 (37) | |

|

| |||

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 377 | 155 (48) | 0.004 |

| No | 249 | 74 (30) | |

|

| |||

| Positive LN | |||

| Yes | 248 | 98 (41) | 0.20 |

| No | 378 | 131 (35) | |

|

| |||

| AJCC Stage | |||

| I | 266 | 88 (33) | 0.01 |

| II | 293 | 116 (40) | |

| III | 44 | 23 (52) | |

|

| |||

| BMI | |||

| <20 | 33 | 17 (51) | 0.04† |

| 20 – <25 | 219 | 91 (41) | |

| 25 – <30 | 213 | 69 (32) | |

| ≥30 | 161 | 53 (33) | |

For each variable, the number of patients in each category are listed, followed by the percent of those patients that have a documented discussion of reconstruction in the chart. p Values were derived using Mantel-Haenszel Test for Trend for ordered variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

Some categories do not add up to 626 because approximately 3 of patients were missing at least one variable.

Because of weighting as described in the methods section, counts and percentages may not correlate exactly due to rounding differences.

The p value is derived using a t-test treating BMI and age as continuous variables.

The p value is calculated comparing Caucasian patients to all other groups.

Overall, 176 of 249 (70.7%) patients with a documented discussion received reconstruction. This rate varied by the number of visits with a documented discussion of reconstruction: 65% for documentation at 1 visit; 70% at 2 and 85% for ≥3 visits (p < 0.0001). Not surprisingly, using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for other covariates, the greatest predictor of reconstruction was medical record documentation of a discussion about reconstruction (OR 5.8 (95% CI 3.3 – 10.3), p<0.0001).

Table 2 examines the rates of reconstruction for the entire cohort as well as the subsets of patients who either did or did not have a documented discussion of reconstruction. The same characteristics that were associated with lower rates of a documented discussion of reconstruction (increasing age, lower education levels, not working full-time, and speaking a primary language other than English) were also associated with lower rates of actually receiving reconstruction. Non-white patients and those born outside the U.S. were also less likely to receive reconstruction. Increasing age and lower levels of education were associated with lower rates of reconstruction regardless of whether there was a documented discussion of reconstruction or not. When limited to the subset of patients where reconstruction was discussed, race, not being born in the US and speaking a primary language other than English correlated with lower rates of reconstruction.

Table 2.

Rates of Reconstruction

| Variable | Overall, n (%)* | p Value | Discussion, n (%)* | p Value | No discussion, n (%)* | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| 25–34 | 10 (100) | <0.0001 | 3 (100) | 0.0019 | 7 (100) | <0.0001† |

| 35–44 | 26 (71) | 15 (81) | 11 (62) | |||

| 45–54 | 99 (58) | 56 (75) | 43 (45) | |||

| 55–64 | 66 (44) | 48 (66) | 18 (23) | |||

| 65–74 | 34 (22) | 28 (62) | 7 (6) | |||

| 75+ | 7 (7) | 6 (41) | 1 (1) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Born in US | ||||||

| No | 23 (29) | 0.049 | 10 (37) | 0.0001 | 13 (25) | 0.61 |

| Yes | 220 (40) | 146 (73) | 73 (21) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Primary language | ||||||

| English | 229 (41) | 0.002 | 154 (72) | <0.0001 | 74 (21) | 0.82 |

| Other | 7 (16) | 0 | 7 (20) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 16 (33) | 0.002† | 9 (68) | 0.018† | 7 (20) | 0.12‡ |

| Asian | 7 (31) | 5 (43) | 2 (20) | |||

| Hispanic | 19 (30) | 9 (43) | 10 (24) | |||

| Caucasian | 217 (41) | 141 (71) | 76 (23) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Any insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 239 (40) | 0.009 | 153 (68) | 0.25 | 86 (23) | 0.016 |

| No | 3 (12) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Employment | ||||||

| Full-time | 134 (50) | <0.0001 | 83 (70) | 0.70 | 51 (34) | <0.0001 |

| Part-time | 28 (39) | 15 (60) | 13 (28) | |||

| Not working | 79 (28) | 57 (68) | 22 (11) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| < 8th grade | 1 (3) | <0.0001 | 1 (31) | 0.001 | 0 (0) | 0.0003 |

| Some HS | 5 (17) | 3 (45) | 2 (10) | |||

| HS grad/GED | 49 (30) | 29 (56) | 20 (18) | |||

| Some college | 100 (47) | 59 (71) | 41 (31) | |||

| College grad | 38 (46) | 30 (69) | 8 (20) | |||

| > College grad | 45 (52) | 30 (85) | 15 (30) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Radiation | ||||||

| Yes | 77 (33) | 0.023 | 39 (56) | 0.007 | 39 (24) | 0.47 |

| No | 165 (42) | 228 (74) | 48 (20) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Co-mordities | ||||||

| Yes | 168 (44) | 0.001 | 57 (66) | 0.51 | 18 (12) | <0.0001 |

| No | 75 (31) | 100 (70) | 68 (28) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 182 (48) | <0.0001 | 111 (72) | 0.17 | 71 (32) | <0.0001 |

| No | 61 (24) | 46 (62) | 15 (9) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Positive LN | ||||||

| Yes | 98 (38) | 0.64 | 65 (66) | 0.58 | 28 (19) | 0.26 |

| No | 150 (40) | 91 (70) | 58 (24) | |||

|

| ||||||

| AJCC Stage | ||||||

| I | 99 (37) | 0.98 | 63 (72) | 0.11 | 36 (20) | 0.65 |

| II | 120 (41) | 81 (70) | 38 (22) | |||

| III | 14 (31) | 11 (50) | 2 (10) | |||

|

| ||||||

| BMI | ||||||

| <20 | 11 (34) | 0.02 | 10 (59) | 0.98 | 1 (9) | 0.05# |

| 20 – <25 | 103 (47) | 69 (76) | 34 (26) | |||

| 25 – <30 | 68 (32) | 36 (53) | 32 (22) | |||

| ≥30 | 60 (37) | 42 (79) | 19 17) | |||

For each variable, the number and percentage of patients who receive reconstruction is presented for the entire cohort of patients as well as the subset of patients with and without a documented discussion of reconstruction as an option. p Values were derived using Mantel-Haenszel Test for Trend for ordered variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

Due to weighting as described in the methods section, counts and percentages may not correlate exactly due to rounding differences.

The p value is derived using a t-test treating BMI and age as continuous variables.

The p value is calculated comparing white patients to all other groups.

In addition, the following clinical and disease-specific independent variables were found to be significantly associated with receiving reconstruction on univarite analysis and considered for inclusion in the final multivariable models: comorbidity (p = 0.001); chemotherapy use (p<0.0001); XRT (p = 0.02); and body mass index (p = 0.02). AJCC stage and lymph node involvement were not associated with likelihood of reconstruction on univariate analysis. If we look specifically at the subset of patients who had a documented discussion of reconstruction, only receipt of radiation was associated with subsequent reconstruction (p= 0.007). There was no significant association for the receipt of chemotherapy, presence of comorbidities, AJCC stage, lymph node involvement, or body mass index. When we look at receipt of reconstruction in those patients without a documented discussion of reconstruction, the presence of co-morbidities (p<0.0001), use of chemotherapy (p<0.0001), and BMI (p= 0.05) were all significantly associated with reconstruction on unadjusted analysis. There was no association for receipt of radiation, AJCC stage or LN status for this subset of patients.

Tables 3, 4 and 5 show the results of the multivariable models for documentation of a discussion of reconstruction, reconstruction overall and reconstruction contingent on a discussion. Independent predictors of medical record documentation regarding a discussion of reconstruction that persisted on multivariable modeling include age (OR 0.59 per decade, 95%CI 0.50 to 0.71), educational level (OR 3.3 for college grad v. less than HS grad, 95%CI 1.4 to 7.8), and post-mastectomy radiation (OR 0.54, 95%CI 0.38 to 0.76). (Table 3) These same characteristics, along with body mass index, were also independently predictive of reconstruction. (Table 4) The discussion of reconstruction as an option was less likely to result in the patient actually receiving reconstruction if they were older (OR 0.55 per decade, 95%CI 0.37 to 0.80), Hispanic (OR 0.35, 95%CI 0.13 to 0.94), and received post-mastectomy radiation (OR 0.34, 95%CI 0.17 to 0.66) while patients who were born in the US were more likely to receive reconstruction given a documented discussion (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 10.6). (Table 5)

Table 3.

Multivariable Model to Determine Predictors of Documentation of a Discussion Regarding Reconstruction as an Option

| Variable | OR | 95 CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per decade) | 0.59 | 0.50 – 0.71 | <0.0001 |

| Education | 0.020 | ||

| < High school graduate | Ref | ||

| High school graduate or some college | 2.6 | 0.99 – 6.7 | |

| College graduate or more | 3.3 | 1.4 – 7.8 | |

| Radiation | 0.54 | 0.38 – 0.76 | 0.0005 |

n = 606 with 244 having documentation of discussion; c statistic = 0.702. The following variables were considered, but not included in the final model: AJCC stage, employment status, insurance status, African-American race, receipt of chemotherapy, body mass index.

Table 4.

Multivariable Model to Determine Predictors of Reconstruction.

| Variable | OR | 95 CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per decade) | 0.33 | 0.26 – 0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Race (Caucasian versus other) | 2.8 | 1.2 – 6.6 | 0.016 |

| Education | 0.024 | ||

| < High school graduate | Ref | ||

| High school graduate or some college | 3.3 | 0.94 – 11.4 | |

| College graduate or more | 4.8 | 1.5 – 15.3 | |

| Radiation | 0.38 | 0.24 – 0.59 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (per point) | 0.96 | 0.92 – 0.99 | 0.029 |

n= 605 with 245 patients receiving reconstruction; c statistic = 0.785. The following variables were considered, but not included in the final model: employment status, receipt of chemotherapy, whether the patient was born in US, insurance status, presence of comorbid conditions.

Table 5.

Multivariable Model to Determine Predictors of Reconstruction Given Documentation that a Discussion Regarding Reconstruction Took Place

| Variable | OR | 95 CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per decade) | 0.55 | 0.37 – 0.80 | 0.002 |

| Born in the U.S. | 3.5 | 1.1 – 10.6 | 0.03 |

| Hispanic | 0.35 | 0.13 – 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Radiation | 0.34 | 0.17 – 0.66 | 0.001 |

n = 243 with 172 patients receiving reconstruction; c statistic = 0.675. The following variables were considered, but not included in the final model: African-American race and educational level.

The final model investigated predictors of reconstruction among patients who did not have a documented discussion of reconstruction. Only age (OR 0.28 per decade (95%CI 0.20 to 0.40), p < 0.0001) was a statistically significant predictor. No other variable added significantly to the predictive model of that single variable.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed variations in the likelihood of reconstruction according to age, education and race after adjusting for clinical factors. These differences appear to be at least in part related to patient-provider discussion of reconstruction as an option. Medical record documentation of a discussion regarding reconstruction was less prevalent in older, less educated patients. Furthermore, following a documented discussion of reconstruction, reconstruction was less likely if a patient was older, Hispanic or born outside of the U.S.

The eradication of racial and socioeconomic disparities in healthcare has been identified as a national healthcare priority. While few would argue with this goal, there is some ambiguity, based on the principle of patient autonomy about whether racial or socioeconomic differences that reflect patient preference or values should be included under the heading of disparities.25, 26 For many procedures, such as amputations, revascularization for peripheral vascular disease or renal transplant, patient preferences play a small role and disparities are more readily apparent.27, 28

Patterns of use are more difficult to interpret for elective procedures, like post-mastectomy reconstruction, or procedures with equivalent outcomes, such as breast conserving surgery with radiation and modified radical mastectomy. In these cases, the choice of procedure is a complex decision, influenced by the clinical scenario, access to care, patient preferences, the providers’ clinical approach and their interaction with the patient.29–31 Optimally, clinical decisions in such cases should reflect individual patient preference and not bias on the part of physicians.21, 32–34 This requires that a discussion of potential options be presented to the patient in an informative and comprehensible manner regardless of race, education, insurance or primary language spoken.

In this paper, we investigate the role that such discussions play in explaining variations in the utilization of post-mastectomy reconstruction according to race and socioeconomic status. There were fewer discussions of reconstruction options among patients that were older and less educated. While decisions about reconstruction following mastectomy should rest primarily on clinical considerations (such as radiation and obesity), we also observed variation in the likelihood of reconstruction according to age, education and race.

Age is a complex issue with regards to reconstruction. Older patients are more likely to have more co-morbidities and poorer performance status - clinical factors that may lead physicians to discuss reconstruction less frequently, but may also influence the patient’s preferences and willingness to tolerate a purely elective procedure. Additionally, marital status was not included in our data set and being a widow has been previously shown to correlate with decreased rates of reconstruction.35 Other work suggests certain psychological characteristics could explain the lower rates of reconstruction observed in older patients. Perceived importance of body image, a lack of fear regarding surgery and the ability to discuss surgical choices with a partner were associated with a greater likelihood of reconstruction.17 While these issues may play a role, it’s important to recognize other possible etiologies of the age disparities that have been documented in the treatment of breast cancer.33, 36–38 Documented variations in the patient-physician interaction based on age have been linked with differences in the likelihood that appropriate quality breast cancer care was received.39, 40 To avoid age bias, reconstruction should be discussed with older patients so that an informed decision based on the clinical situation and patient preferences can be reached.

While a lower prevalence of discussions regarding reconstruction appears to play a role in explaining disparities in reconstruction, our data do not address whether the physician or the patient initiated the discussion. It is possible that women who are younger and more educated are more likely to initiate a discussion of reconstruction with their provider, thus accounting for the higher rates. Whether the provider or the patient initiates the discussion, the observed differences still reflect the physician’s behavior. Physicians should systematically address the issue of reconstruction, starting with whether or not the patient is a reasonable candidate based on the clinical situation, with all patients rather than relying on patients to inquire about it.

Considering Figure 1, we next wanted to investigate the factors that predict reconstruction conditional on a documented discussion. Older age was again associated with a lower likelihood of reconstruction. As suggested above, this may reflect patient preference or qualitative aspects of the patient-physician communication. On multivariable modeling the other independent predictors of reconstruction after a discussion is documented are whether the patient was born in the U.S. and Hispanic ethnicity. While this may reflect ethnic differences in patient preferences, it may also be due to communication difficulties between the patient and provider, due to language or cultural barriers or otherwise. Further evidence that the quality of the communication during the discussion of reconstruction may play a role is suggested by the lower rates of reconstruction among patients who speak a language other than English as their primary language. While 72% of patients who primarily spoke English went on to receive reconstruction after discussing it with their providers, no patient with a primary language other than English did. The small sample size (8 patients) in this latter group limited the use of this variable in our multivariable model. In order to ensure adequate comprehension of the patient survey, the study was limited to patients who spoke English, so it is difficult to draw conclusions about the language effect. Our data do not allow us to differentiate between patient preference and qualitative differences in patient-physician communication as the underlying explanation for the different rates of reconstruction following a discussion about the option, but there are plausible reasons to think that both play a role.

Our analysis has several other important limitations. By design, the patients included in this analysis were contacted three years after diagnosis. While delay following diagnosis may ensure complete information about chemotherapy, radiation, and outcomes, it does not have any advantage for surgical analyses such as this and may lead to lower response rates and more difficulty with chart abstraction. Since documentation of reconstruction is one of the primary outcomes for this analysis, we directly investigated this potential for bias.

Twenty-two percent of patients who lacked documentation of a discussion regarding reconstruction actually received reconstruction; however, reconstruction is necessarily preceded by discussion, suggesting misclassification. This lack of documentation would alter our results only if it were related to patients’ socioeconomic characteristics. In order to determine whether this was the case, we tested whether the 22% of patients with reconstruction but without documentation of a discussion differ from the patients who do not have reconstruction. Older patients were less likely to receive reconstruction in the absence of a documented discussion; however none of the other covariates were significant, suggesting minimal, if any, documentation bias related to socioeconomic factors or race.

Another important limitation to this study relates to insurance status. Given the high cost and elective nature of reconstruction, the quality of an individual’s insurance plan is likely to influence their decision to pursue reconstruction. These differences are not well-measured by our binary treatment of insurance (any insurance vs. none). Differences in insurance coverage may explain a portion of the observed socioeconomic variations and cannot be adequately addressed in this study.

The likelihood of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction varies based on the race and socioeconomic status of the patient. This study suggests three potential explanations for this: (1) patient-provider discussions of the option of reconstruction occur less frequently in vulnerable populations; (2) there are differences in qualitative aspects of patient-physician communication during these discussions, potentially based on language, educational, or cultural barriers; and (3) age-based and ethnic or cultural differences in patient preferences regarding reconstruction. While patient preferences should be respected, an informative discussion of reconstruction as an option is required for meaningful decision-making. It is the responsibility of physicians to universally address the issue of reconstruction (within the constraints of the clinical situation) with all women undergoing a mastectomy regardless of age, race, or socioeconomic status. Furthermore, physician-patient communication during these discussions should be optimized through the use of interpreters and educational materials that ensure comprehension regardless of primary language, ethnicity, or educational level. Such efforts to increase and improve discussions of reconstruction for these vulnerable populations may decrease disparities in the utilization of this procedure.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Declared: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alderman AK, McMahon L, Jr, Wilkins EG. The national utilization of immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction and the effect of sociodemographic factors. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:695–703. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041438.50018.02. discussion 704–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desch CE, Penberthy LT, Hillner BE, et al. A sociodemographic and economic comparison of breast reconstruction, mastectomy, and conservative surgery. Surgery. 1999;125:441–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall SE, Holman CD. Inequalities in breast cancer reconstructive surgery according to social and locational status in Western Australia. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:519–525. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(03)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrow M, Scott SK, Menck HR, et al. Factors influencing the use of breast reconstruction postmastectomy: a National Cancer Database study. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00747-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polednak AP. How frequent is postmastectomy breast reconstructive surgery? A study linking two statewide databases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:73–77. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowland JH, Desmond KA, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1422–1429. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.17.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian CK, Niland JC, Edge SB, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of the socioeconomic determinants of breast reconstruction: A study of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Ann Surg. 2006;243:241–249. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197738.63512.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow M, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, et al. Correlates of breast reconstruction: results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2005;104:2340–2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng JF, Kronowitz SJ, Sun CC, et al. The effect of ethnicity on immediate reconstruction rates after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:1514–1523. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pusic A, Thompson TA, Kerrigan CL, et al. Surgical options for the early-stage breast cancer: factors associated with patient choice and postoperative quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1325–1333. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199910000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulley AG., Jr Developing skills for evidence-based surgery: ensuring that patients make informed decisions. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:181–192. xi. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepucha KR, Fowler FJ, Jr, Mulley AG., Jr Policy support for patient-centered care: the need for measurable improvements in decision quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;(Suppl Web Exclusives):VAR54–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dein S. Explanatory models of and attitudes towards cancer in different cultures. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:119–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones C. The impact of racism on health. Ethn Dis. 2002;12:S2-10-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whaley AL. Ethnicity/race, ethics, and epidemiology. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:736–742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Losken A, Carlson GW, Schoemann MB, et al. Factors that influence the completion of breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52:258–261. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000110560.03010.7c. discussion 262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananian P, Houvenaeghel G, Protiere C, et al. Determinants of patients’ choice of reconstruction with mastectomy for primary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:762–771. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molenaar S, Oort F, Sprangers M, et al. Predictors of patients’ choices for breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy: a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2123–2130. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Sharf BF, et al. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients’ perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:904–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status(SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keating NL, Weeks JC, Borbas C, Guadagnoli E. Treatment of early stage breast cancer: do surgeons and patients agree regarding whether treatment alternatives were discussed? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;79:225–231. doi: 10.1023/a:1023903701674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: how can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:626–634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider EC, Epstein AM, Malin JL, et al. Developing a system to assess the quality of cancer care: ASCO’s national initiative on cancer care quality. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2985–2991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Services USDoHaH. Healthy People 2010: With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Gibbons G, et al. The influence of race on the use of surgical procedures for treatment of peripheral vascular disease of the lower extremities. Arch Surg. 1995;130:381–386. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040043006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1661–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greer AL, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL, Wu ZH. Bringing the patient back in. Guidelines, practice variations, and the social context of medical practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;18:747–761. doi: 10.1017/s0266462302000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz SJ, Lantz PM, Janz NK, et al. Patterns and correlates of local therapy for women with ductal carcinoma-in-situ. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3001–3007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reaby LL. Reasons why women who have mastectomy decide to have or not to have breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1810–1818. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keating NL, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, et al. Treatment decision making in early-stage breast cancer: should surgeons match patients’ desired level of involvement? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1473–1479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madan AK, Aliabadi-Wahle S, Beech DJ. Age bias: a cause of underutilization of breast conservation treatment. J Cancer Educ. 2001;16:29–32. doi: 10.1080/08858190109528720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voogd AC, Repelaer van Driel OJ, Roumen RM, et al. Changing attitudes towards breast-conserving treatment of early breast cancer in the south-eastern Netherlands: results of a survey among surgeons and a registry-based analysis of patterns of care. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joslyn SA. Patterns of care for immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1289–1296. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000156974.69184.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold HT, Dick AW. Variations in treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ in elderly women. Med Care. 2004;42:267–275. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114915.98256.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edge SB, Gold K, Berg CD, et al. Patient and provider characteristics that affect the use of axillary dissection in older women with stage I–II breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2534–2541. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enger SM, Thwin SS, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer treatment of older women in integrated health care settings. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4377–4383. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA. Breast cancer treatment in older women: impact of the patient-physician interaction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1138–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thwin SS, Fink AK, Lash TL, Silliman RA. Predictors and outcomes of surgeons’ referral of older breast cancer patients to medical oncologists. Cancer. 2005;104:936–942. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]