Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are immune cells specialized to capture, process and present antigen to T cells in order to initiate an appropriate adaptive immune response. The study of mouse DC has revealed a heterogeneous population of cells that differ in their development, surface phenotype and function. The study of human blood and spleen has shown the presence of two subsets of conventional DC including the CD1b/c+ and CD141+CLEC9A+ conventional DC (cDC) and a plasmacytoid DC (pDC) that is CD304+CD123+. Studies on these subpopulations have revealed phenotypic and functional differences that are similar to those described in the mouse. In this study, the three DC subsets have been generated in vitro from human CD34+ precursors in the presence of fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) and thrombopoietin (TPO). The DC subsets so generated, including the CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ cDCs and CD123+ pDCs, were largely similar to their blood and spleen counterparts with respect to surface phenotype, toll-like receptor and transcription factor expression, capacity to stimulate T cells, cytokine secretion and cross-presentation of antigens. This system may be utilized to study aspects of DC development and function not possible in vivo.

Keywords: dendritic cells, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, thrombopoietin

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen presenting cells crucial for the activation of a T-cell response. DCs have been well studied in mouse lymphoid tissues and a number of distinct subsets have been identified. The plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) are the major producers of type-1 interferons in response to toll-like receptor stimulation.1,2,3 The conventional (or ‘myeloid') DCs (cDCs) that include the CD8+ and CD8− subsets in mice4 are the major presenters of antigen to T cells. In particular, the CD8+ cDCs are the major cross-presenters of antigen and are capable of initiating a CD8+ T-cell response. They also produce large amounts of the cytokine IL-12p70 that confers upon them the capacity to polarize a Th1 response.5 The CD8− cDCs produce high levels of inflammatory chemokines capable of attracting other immune cells to the area.6 It has been shown that these three subtypes of mouse DCs can be differentiated in vitro from bone marrow precursors in the presence of fms-like tyrosine kinase ligand (Flt3L). The cultured DCs can be generated in large quantities with ease, and share similar properties to their in vivo counterparts.7 Of note, the cultured DCs do not express CD8, but the markers that are coexpressed by CD8+ and CD8− DCs including CD24, CD11b and Sirpα are used to distinguish the DC subsets in vitro. This established culture system has enabled detailed studies of the specialized function and development of murine DC subsets.8,9,10,11

The study of human DC has lagged behind. Initial studies on human DC have focused on DC found in blood. Four subtypes have been identified including the CD304+ (BDCA4) pDCs and the cDCs that include the CD141+ (BDCA3) and CD1b/c+ (BDCA1) subsets.12 A fourth subset that is CD16+ has been suggested to be a subset of both DC12 and monocytes,13 but is now considered to be a monocyte in a recent reclassification of the monocyte and DC subsets in human blood.14 The CD141+ DCs have been suggested to be equivalent to the mouse CD8+ DCs sharing a similar transcriptional signature15 and expression of Necl2, CLEC9A and XCR1.16,17,18,19,20,21 Furthermore, the CD141+ DCs have been shown to produce IL-12p70 and cross-present antigen,20,21,22,23 both characteristics of the mouse CD8+ DC subset. The CD1b/c+ DC is thought to be the equivalent of the mouse CD8− DC, based on a similar transcriptional profile.15 Recently, the four populations of human DCs identified in blood have also been found in human spleen with similar phenotype and functions.24 Human spleen are difficult to obtain and thus, a culture system that is capable of generating the DC subsets in vitro would be of great use for further DC research.

A number of different culture systems have been studied for human DC differentiation; however, correlation between the cultured DC subtypes and those found in human blood and lymphoid organs has been difficult. Recently, it has been shown that culturing human blood CD34+ haemopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), Flt3L and tumour-necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) generates two DC subsets that are equivalent functionally to the epidermal and dermal skin-derived DCs found in situ.25 Culturing HSCs enriched from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized blood in the presence of Flt3L and thrombopoietin (TPO) has been shown to generate in good yield, functional pDC that are equivalent to their in vivo counterparts in their capacity to produce interferon (IFN)-α in response to TLR stimulation.26,27 Most recently, Poulin et al.23 have developed a culture system that supports the generation of CD141+CLEC9A+ DCs from cord blood precursors. However, despite many different culture conditions used to generate functional DC in vitro, a culture system capable of generating the pDC and the cDC subtypes including the CD1b/c+ and CD141+CLEC9A+ DC found within human lymphoid tissue and blood has not been described.

In this study, we show that distinct DC subsets including the CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ cDC and CD123+ pDC can be grown in culture from CD34+ precursors of G-CSF-mobilized blood in the presence of Flt3L and TPO. These DC share many similarities to those DC found within human blood and spleen. This is the first study to identify and functionally characterize all three major subtypes of DCs in a single in vitro culture system.

Materials and methods

Isolation of CD34+ haematopoietic stem cells from blood of adult G-CSF-mobilized donors and generation of DC in vitro

CD34+ haematopoietic stem cells were isolated from leukapheresis blood products from G-CSF-mobilized donors. Cell suspensions of G-CSF-mobilized blood were prepared and total mononuclear cells collected after Ficoll density centrifugation. CD34+ HSCs were purified using Miltenyi MACS CD34+ cell isolation reagents and the MACS system according to manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Cells were cryopreserved in foetal calf serum (FCS) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide in liquid nitrogen until use. For culture, HSCs were cultured in 96-well flat bottom plates or 24-well plates at between 1×105 and 5×105 cells/ml in Yssel's medium (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento CA, USA) supplemented with 10% human AB serum, and either HuGM-CSF (100 ng/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), HuSCF (25 ng/ml; eBioscience) and HuTNF-α (2.5 ng/ml; eBioscience) or HuFlt3L (100 ng/ml; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) and HuTPO (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Cell cultures were refreshed every 5 days with Yssels's medium containing the growth factors and split on confluence. Cells were harvested at day 21.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting of DCs

Cells were labelled with antibodies against surface markers by resuspending at 1×106 cells in 10 µl of staining solution (HTPBS/FCS-EDTA) containing conjugated monoclonal antibody (mAbs, or polyclonal in the case of XCR1) for 25 min and washed with HTPBS/FCS-EDTA. For XCR1, cells were first blocked with human AB serum for 15 min before addition of the antibody. Each mAb was conjugated to R-phycoerythrin (PE), fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC), allophycocyanin or biotin (all Molecular Probes—Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). Flow cytometry analysis and sorting were performed on the LSRII and FACSaria (BD Biosciences) instruments. For sorting, cells were stained with anti-HLA-DR-PE (clone 2.06), CD11c-PECy7 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD1b/c-APC, CLEC9A-FITC (clone 4C6), CD123-PE (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) and CD14-alexa680 (clone FMC17). For analysis, CD123-FITC (BD Biosciences), CLEC9A-APC, SIRPα-biotin (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD40-FITC, CD80-FITC, CD83-FITC, CD86-FITC (BD Biosciences), polyclonal XCR1-PE (R&D systems) and CD11b-PE (clone OKM1) were also used.

DC and monocyte stimulation for analysis of cytokine production

Sorted cultured DC subsets and monocytes were cultured at 1×106/ml in 96-well round bottom plates for 24 h in the presence of CpG A and CpG C (1 mM) (Geneworks, Hindmarsh, SA, Australia), soluble trimeric CD40L (1 mg/ml) (kind gift from Dr D. Lynch, Amgen), huGM-CSF (100 ng/ml) (eBioscience), huIL-4 (40 ng/ml) (eBioscience), huIFN-γ (40 ng/ml) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), Poly(I∶C) (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Culture supernatants were collected and stored at −20 °C until cytokine detection using a 14-plex Milliplex human cytokine bead array (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) as per manufacturer's instructions.

Allogeneic mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR)

Blood CD4+ T cells were isolated from buffy coats using a magnetic bead-based CD4 T cell-negative isolation kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+ T cells were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (0.5 mM) and then washed twice with Hank's balanced salt solution. CFSE-labelled purified allogeneic CD4+ T cells (50 000) from blood were cocultured with sorted cultured DCs and monocytes for 96 h in 96-well V-bottom plates. T-cell proliferation was determined by resuspending cells in HT-PBS/3% FCS containing a known number of latex beads (BD Biosciences). Numbers of CFSElo live dividing T cells were determined relative to the number of latex beads added per well.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was prepared from purified DC populations and monocytes using the RNeasyMini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as per the manufacturer's instructions. RNA (up to 2 µg) was treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using random primers (Promega) and Superscipt II reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL—Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed to determine the expression of Gapdh, TLR3, TLR7, TLR9, IRF4 and IRF8 using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and a light cycler (Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The specific primers for RT-PCR were as follows:

GAPDH: 5′-TGGTCACCAGGGCTGCTTTT-3′, 5′-ATCTCGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTG-3′

TLR3: 5′-GTGCCCCCTTTGAACTCTTTTT-3′, 5′-AAATGTTCCCAGACCCAATCCT-3′

TLR7: 5′-CTCCTTGGGGCTAGATGGTTTC-3′, 5′-TAA TGGTGAGGGTGAGGTTCGT-3′

TLR9: 5′-GAGTGCTGGACCTGAGTGAGAA-3′, 5′-ATCGAGTGAGCGGAAGAAGATG-3′

IRF4: 5′-TCCAGGTGACTCTATGCTTTGGA-3′, 5′-CTGGATTGCTGATGTGTTCTGG 3′

IRF8: 5′-CTTCGACACCAGCCAGTTCTTC-3′, 5′-ACAGCTCTTCCCAGCCTCTTCT-3′.

An initial 15-min activation step at 95 °C was followed by 35–45 cycles of 15 s at 94 °C (denaturation), 20–30 s at 50–60 °C (annealing) and 10–12 s at 72 °C (extension), followed by melting point analysis. The expression level for each gene was determined using a standard curve prepared from 10−2–10−6 pg of specific DNA fragment and then expressed as a ratio to GAPDH.

Cross-presentation assay

DC subsets were isolated from cultures and seeded at 4 000 per well in a 96-well U-bottom plate in 200 µl complete medium (HT-RPMI, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 10 mM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 5% pooled human serum (Australian Red Cross Blood Service), 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). DC subsets were pre-incubated with influenza virus protein antigen (New Caledonia 20/1999 H1N1, WHO; the virus had been propagated in the allantoic cavity of embryonated hens' eggs, inactivated with UV light and formaldehyde, purified by centrifugation and disrupted with sodium deoxycholate). After 2.5 h, DCs were washed twice with complete medium and transferred to a new 96-well U-bottom plate and incubated with a human HLA-matched CD8+ T-cell clone (10 000 cells/well) specific for the influenza virus antigen MP 58–66 epitope for 2 h. All cells were then transferred onto an ELISpot plate (Millipore) that was coated with anti-human IFN-γ antibody (Mabtech, Nacka Strand, Sweden) and incubated overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2. IFN-γ production by the T cells was detected on the ELISpot plate after incubation with anti-IFN-γ mAb-biotin for 1 h, followed by streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase for 1 h and NBT/BCIP for 20 min (all reagents from Resolving Images, Mabtech). Between incubations, plates were washed three times with PBS–0.05% Tween 20. IFN-γ spots per well were counted on an ELR02 ELISpot reader and analysed using ELISpot Reader V4.0 software (Autoimmun Diagnostika, Strassberg, Germany).

Results

Generation of DC subtypes in vitro from human haemopoietic stem cells

A number of different culture systems have been used to generate DC subsets in vitro. We compared two such systems. It has been shown that HLA-DR+CD11c+CD1a+CD80+CD86+ DCs can be generated from G-CSF-mobilized CD34+ progenitors in the presence of GM-CSF, stem cell factor (SCF) and TNF-α.28 It has also been shown that CD11c+ cDCs and CD123+ pDCs can be differentiated in vitro from CD34+ HSC obtained from human foetal liver and adult G-CSF-mobilized blood, in the presence of Flt3L and TPO (FL/TPO cultures).26 We compared these two culture conditions for the ability of CD34+ HSC isolated from G-CSF-mobilized blood to differentiate into the cDC subsets found in vivo in human blood.

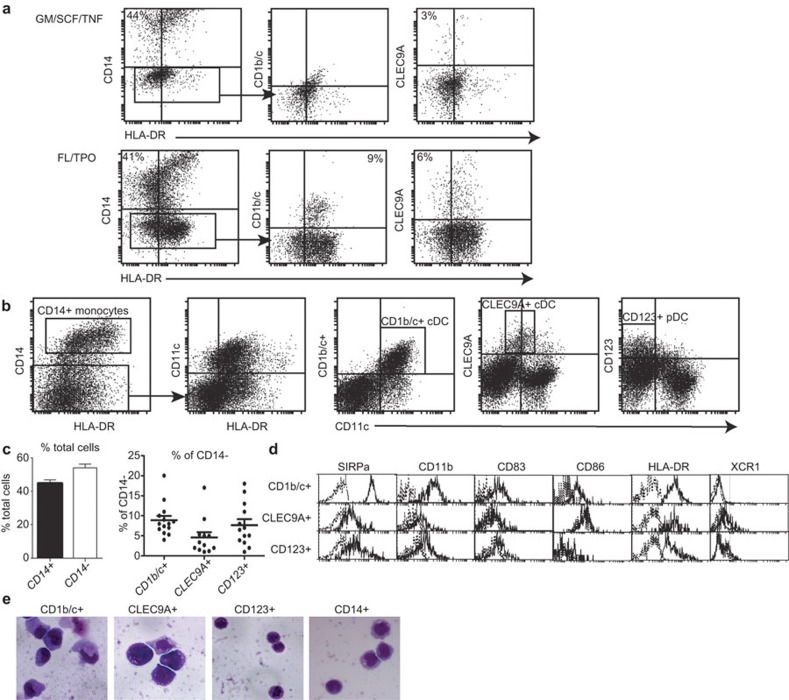

The cultures containing GM-CSF/SCF/TNF-α did not yield CD1b/c+ cDC at any of the time points tested including at days 7, 14 and 21 (Figure 1a, top panel). CLEC9A+ cDCs were identified, albeit at reduced proportions compared to the FL/TPO cultures. In contrast, the FL/TPO cultures yielded both the CD1b/c+ cDCs and the CLEC9A+ cDCs at day 21 (Figure 1a, bottom panel). These cultures were thus chosen for further analysis and characterisation and the DCs generated herein referred to Flt3L-derived DCs.

Figure 1.

Surface phenotype and morphology of Flt3L-derived DCs. (a) CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF, SCF and TNF-α (top panel) or Flt3L and TPO (bottom panel) for 21 days. Cells were harvested and immunofluorescently labelled with DC markers HLA-DR, CD1b/c and CLEC9A and the monocyte marker CD14 and analysed by flow cytometry. To identify the DC subsets, CD14− cells were gated, and expression of HLA-DR, CD1b/c and CLEC9A was analysed. CD14−HLADR+CD1b/c+ DCs were identified in FL/TPO cultures and not in GM/SCF/TNF cultures, while CD14−HLADRint/hiCLEC9A+DC were found in both culture conditions. (b) Flt3L-derived cells harvested at day 21 were immunofluorescently labelled with DC markers CD11c, HLA-DR, CD1b/c, CLEC9A and CD123, and the monocyte marker CD14 and analysed by flow cytometry. CD14+ monocytes were present. A gate was placed on CD14− cells (panel 1) and this CD14− population was analysed for its expression of CD11c and HLA-DR (panel 2). To further study the DC populations, expression of CD11c and CD1b/c (panel 3), CLEC9A (panel 4) and CD123 (panel 5) was analysed among the CD14− gated population. Three populations, namely, CD14−CD11c+CD1b/c+, CD14−CD11cintCLEC9A+ and CD14−CD11c−CD123+ pDCs were identified. (c) Proportions of CD14+ and CD14− cells amongst the total population were calculated (left panel) and the proportions of CD1b/c+, CLEC9A+ and CD123+ cells among the CD14− population were calculated (right panel). (d) The DC subsets identified were further fluorescently labelled with antibodies against SIRPα, CD11b, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR and XCR1. The solid line represents staining for these molecules on gated DC subsets; the dotted line is background fluorescence on unstained cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (e) Cytospins were prepared from sorted populations of the DC subsets and monocytes and morphology was assessed by haematoxylin and eosin staining. Magnification, ×40. DC, dendritic cell; Flt3L, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; SCF, stem cell factor; TNF, tumour-necrosis factor; TPO, thrombopoietin.

CD34+ HSCs comprised approximately 1% of total cells from G-CSF-mobilized blood after Ficoll density centrifugation (data not shown). Purified CD34+ HSCs were cultured in vitro with Flt3L and TPO for 14, 21 and 28 days. In agreement with Chen et al.,26 21 days was optimal for the expansion and development of all DC subsets identified26 and this time point was thus used in all subsequent experiments (data not shown). At day 21, five major populations of cells could be distinguished: CD14+ monocytes, CD14−HLA-DR+CD11c+CD1b/c+ and CD14−HLA-DR+CD11cintCLEC9A+ cDC, HLA-DRintCD11c−CD123+ pDC and HLA-DR−CD11c−CD123−CD1b/c−CLEC9A− cells (subsequently referred to as DC marker-negative cells) (Figure 1b and d). The CLEC9A+ population did not express CD1b/c and vice versa (data not shown). There was a 63±16.8-fold increase in total number of cells over the 21-day period. CD14+ monocytes represented 44% of total cultures. Of the 56% of CD14− cells, CD1b/c+ cDCs comprised an average of 9%, CLEC9A+ cDCs 4.6% and CD123+ pDCs 7.6% (Figure 1c). In the mouse and human systems, the cDC subsets can be distinguished on the basis of CD11b and SIRPα expression.29,30 In vitro, the CD1b/c+ cDCs expressed high levels of CD11b and SIRPα, while the CLEC9A+ cDC expressed low levels of CD11b and SIRPα (Figure 1d), similar to their in vivo counterparts.29,30 Unlike their in vivo counterparts, the CD123+ pDCs did not express CD304 (BDCA4) and the CLEC9A+ cDCs did not express CD141 (BDCA3) (data not shown). However, it has recently been shown that the CD8+ cDCs in mouse and the BDCA3+ cDCs in human blood uniquely express XCR1.21,31,32 The cultured CLEC9A+ DC also expressed this molecule (Figure 1d). CLEC9A is therefore unique to spleen and blood CD141+ DCs16,24 and was thus used as a marker to distinguish this subset in subsequent experiments.

None of the DC subsets expressed CD40 or CD80 (data not shown). However, the CD1b/c+ cDCs did express CD83 and CD86, suggesting that they are more mature than the CLEC9A+ cDCs and CD123+ pDCs (Figure 1d). Cytospin analysis of the three DC subtypes revealed that the CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ cDCs are larger cells compared to the CD123+ pDCs that are small and plasmacytoid-like in morphology (Figure 1e). The CD14+ cells displayed typical monocytic characteristics with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio.

Transcription factor expression by Flt3L-derived DC subsets and monocytes

Given our finding that Flt3L-derived DC subsets were similar in surface phenotype to those found in mouse spleen, and in human blood and spleen, we investigated other properties of Flt3L-derived DCs that in mice and humans demarcate DC subsets. Mouse DC subsets differ in their development, which is controlled by different transcription factors such as interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) IRF4 and IRF8. Mice lacking a functional IRF4 gene have almost no splenic CD4+CD8− cDCs.33,34 In contrast, IRF8 is crucial in the development of mouse CD8+ cDCs and pDCs.34,35

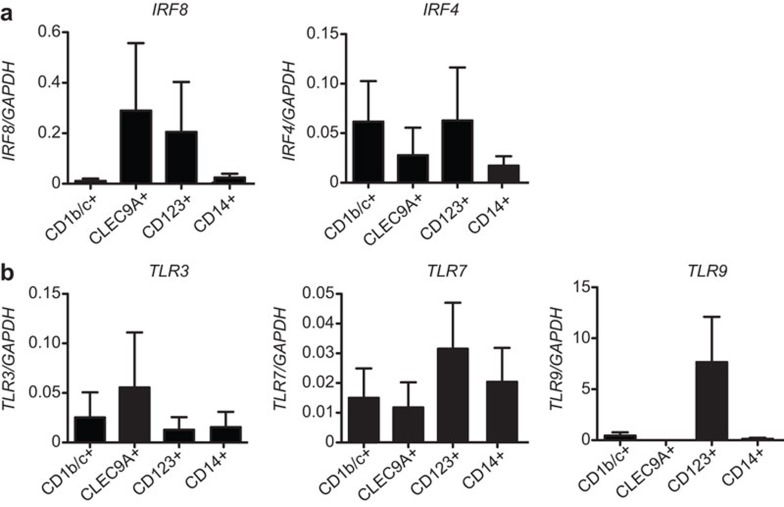

IRF8 and IRF4 expression in human DC subsets and monocytes sorted from day 21 Flt3L cultures were analysed by quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 2a). Overall, the pattern of transcription factor expression in Flt3L-derived DC subsets correlated with that in mouse and human spleen DCs. Flt3L-derived CLEC9A+ cDCs and CD123+ pDCs expressed IRF8 similar to mouse CD8+ cDCs and pDCs and their human equivalents the CD141+ cDCs and CD304+ pDCs. However, in human blood, the pDC expressed IRF8 at higher levels than the CD141+ cDCs, whereas in the cultured system, the pDCs and CLEC9A+ DCs expressed IRF8 at a comparable level. Flt3L-derived CD123+ pDCs expressed IRF4 similar to human pDCs in blood and spleen albeit at lower levels. Interestingly, CD1b/c+ cDCs expressed IRF4 similar to mouse CD8− cDCs, whereas human blood and spleen CD1b/c+ DCs expressed very low levels of IRF424 (Figure 2a). Monocytes expressed only low levels of IRF8 and IRF4 (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Transcription factor and Toll-like receptor expression in Flt3L-derived DCs and monocytes. Quantitative RT-PCR of (a) transcription factors IRF8 and IRF4 and (b) Toll-like receptors TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9 relative to GAPDH in DC subsets and monocytes from Flt3L-derived cultures; CD11c+CD1b/c+, CD11cintCLEC9A+, CD11c−CD123+ and CD14+ monocytes. Results are representative of 3–4 independent experiments. DC, dendritic cell; Flt3L, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; IRF, interferon regulatory factor.

TLR expression by Flt3L-derived DC subsets and monocytes

TLRs are expressed differentially by DC subtypes and monocytes and confer on DCs and monocytes the capacity to respond to specific pathogen-associated molecular patterns. TLR3 binds double stranded RNA and is expressed selectively by mouse CD8+ cDCs and by human blood and splenic CD141+CLEC9A+ cDCs and at lower levels by CD1b/c+ cDCs.36,37 TLR7 binds single-stranded RNA and is expressed by mouse CD8− cDCs and pDCs and by human blood and splenic cDCs and pDCs at low levels.24,36,37 TLR9 binds bacterial CpG and is most highly expressed by mouse pDCs, and all cDCs,7,37 but only expressed by human pDCs.38 Expression of these TLRs in sorted Flt3L-derived DCs and monocytes was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 2b). TLR3 was most highly expressed by CLEC9A+ cDCs and also at moderate levels by CD1b/c+ cDCs similar to human blood and spleen DC, although the difference in expression between the CD1b/c+ DCs and the CLEC9A+ DCs was more pronounced in blood DC.24 Similarly, like human blood DCs, TLR7 was expressed most highly by CD123+ pDCs, and also at moderate levels by the CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ cDCs as well as the CD14+ monocytes, albeit the general expression levels were lower.24 TLR9 was expressed mainly by CD123+ pDC similar to their in vivo counterparts24 (Figure 2b).

Cytokine secretion by Flt3L-derived DCs and monocytes

An important function of DCs is the capacity to secrete cytokines in response to activation. Murine CD8+ cDCs secrete IL-12p70 which polarizes T cells to a Th1 response,5 whereas CD8− cDCs secrete large amounts of inflammatory chemokines including Mip-1α.6 pDCs are the major secretors of type-1 IFN in response to viral stimulation.1,2,3,38 For maximal production of IL-12p70, stimulation with TLR9 together with a cocktail of IL-4, GM-CSF and IFN-γ39 or microbial stimuli together with anti-CD40 is required.40 Given that Flt3L-derived human cDCs did not express TLR9 but differentially expressed TLR3, TLR4 and TLR7, we stimulated them for 24 h with CD40L and a cytokine cocktail to ensure activation of all cDC rather than a particular subset. Since CD123+ pDCs expressed very high levels of TLR9, they were stimulated with CpG A and CpG C. In addition, CD14+ monocytes were sorted and were stimulated with either CD40L and cocktail alone, or in the presence of LPS, a TLR4 agonist. LPS is known to strongly activate monocytes to become cells that produce high levels of IL-1β and IL-6 and which have a capacity to induce human Th17 cells.41 Monocytes derived from the Flt3L cultures expressed high levels of TLR4 (data not shown).

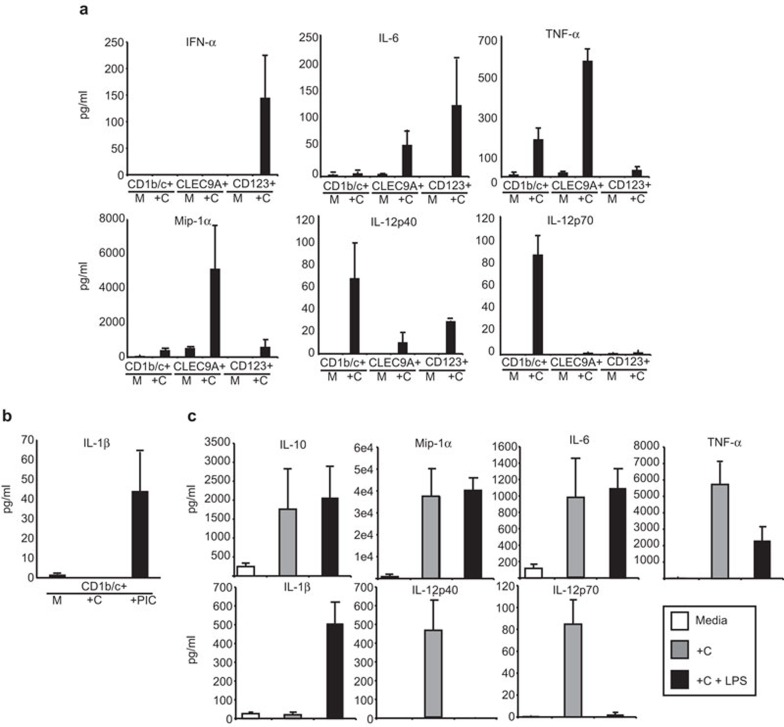

Flt3L-derived pDCs produced IFN-α and IL-6 in response to CpG stimulation (Figure 3a) similar to human blood pDCs. Different from blood pDCs, cultured pDCs did not produce high levels of Mip-1α.

Figure 3.

Cytokine production by Flt3L-derived DCs and monocytes. (a) Sorted Flt3L-derived CD11c+CD1b/c+, CD11cintCLEC9A+ and CD11c−CD123+ were cultured at 1×106/ml for 24 h in medium alone (M) or with a cocktail (+C) containing CD40L (1 mg/ml), IFN-γ (40 ng/ml), GM-CSF (100 ng/ml) and IL-4 (40 ng/ml) for CD11c+CD1b/c+ and CD11cintCLEC9A+, or with CpG A (1 mM) and CpG C (1 mM) for CD11c−CD123+ pDC. Concentrations (pg/ml) of IFN-α, IL-6, TNF-α, Mip-1α, IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 in the culture supernatant were assayed by immunoplex bead array. (b) Sorted Flt3L-derived CD11c+CD1b/c+ were cultured at 1×106/ml for 24 h in medium alone (M), with the cocktail (+C) or with the cocktail and Poly(I∶C) (+PIC) (1 µg/ml) and the concentration (pg/ml) of IL-1β was assayed by immunoplex bead array. (c) Sorted Flt3L-derived CD14+ monocytes were cultured at 1×106/ml for 24 h in medium alone (M) or with CD40L (1 mg/ml), IFN-γ (40 ng/ml), GM-CSF (100 ng/ml) and IL-4 (40 ng/ml) (+C) or in the presence of the cocktail and LPS (1 µg/ml) (+C+LPS). Concentrations (pg/ml) of IL-10, Mip-1α, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 in the culture supernatant were assayed by immunoplex bead array. Results shown as mean (±s.e.m) of at least three independent experiments. DC, dendritic cell; Flt3L, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN, interferon; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; TNF, tumour-necrosis factor.

The CD1b/c+ cDCs produced TNF-α, IL-12p40 and IL-12p70, similar to their blood counterparts.24 It has recently been shown that blood CD1b/c+ DCs produce high levels of IL-1β in the presence of Poly(I∶C) (PIC), a TLR3 agonist compared to unstimulated controls.22 Flt3L-derived CD1b/c+ DCs responded in a similar manner with high levels of IL-1β produced in the presence of PIC but not in its absence (Figure 3b). However, in contrast to blood CD1b/c+ cDCs, Flt3L-derived CD1b/c+ DCs produced only low levels of Mip-1α and IL-6 compared to unstimulated controls.

The CLEC9A+ cDCs produced high levels of TNF-α, Mip-1α and IL-6 and only low levels of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70. The low production of IL-12p70 is similar to the blood CD141+ cDCs.

The CD14+ monocytes in the presence of CD40L and the cocktail produced high levels of IL-10, Mip-1α, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-12p40 and IL-12p70, but only low levels of IL-1β. In addition, when LPS was added, monocytes continued to produce high levels of IL-10, Mip-1α and IL-6, and upregulated production of IL-1β up to 500-fold. In contrast, production of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 was inhibited (Figure 3c).

Overall, the DC subsets and monocytes behaved in a similar way to their in vivo counterparts with respect to cytokine production with some differences.

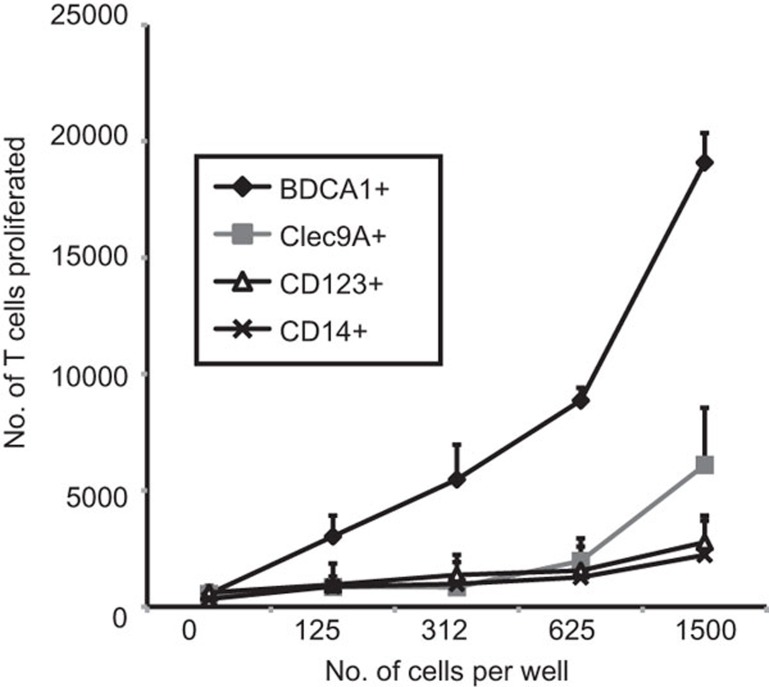

Stimulation of CD4+ T cells in an allogeneic MLR by Flt3L-derived DCs and monocytes

To test the stimulatory capacity of the DC subsets and monocytes identified in Flt3L cultures, CFSE-labelled CD4+ allogeneic T cells from human blood were cocultured with various DC and monocytes sorted from Flt3L cultures for 5 days. T-cell proliferation was determined by enumerating the number of CFSE-low T cells at the end of the culture period. The CD1b/c+ cDCs were the most efficient stimulators of allogeneic CD4+ T cells. The CLEC9A+ cDCs, the CD123+ pDCs and the monocytes stimulated T cells moderately (Figure 4). These results were similar to those found for DC subsets and monocytes in human blood and spleen.24

Figure 4.

Stimulation of CD4+ T cells by Flt3L-derived DCs and monocytes in an MLR. Flt3L-derived CD14+ monocytes, and CD11c+CD1b/c+, CD11cintCLEC9A+ DCs and CD11c−CD123+ pDCs were incubated with CFSE-labelled allogeneic CD4+ human blood T cells. Cell proliferation was measured by counting live CFSE-labelled cells that had divided after 5 days of culture. Results are shown as mean (±s.e.m.) of three independent experiments. CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; DC, dendritic cell; Flt3L, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; MLR, mixed leukocyte reaction; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell.

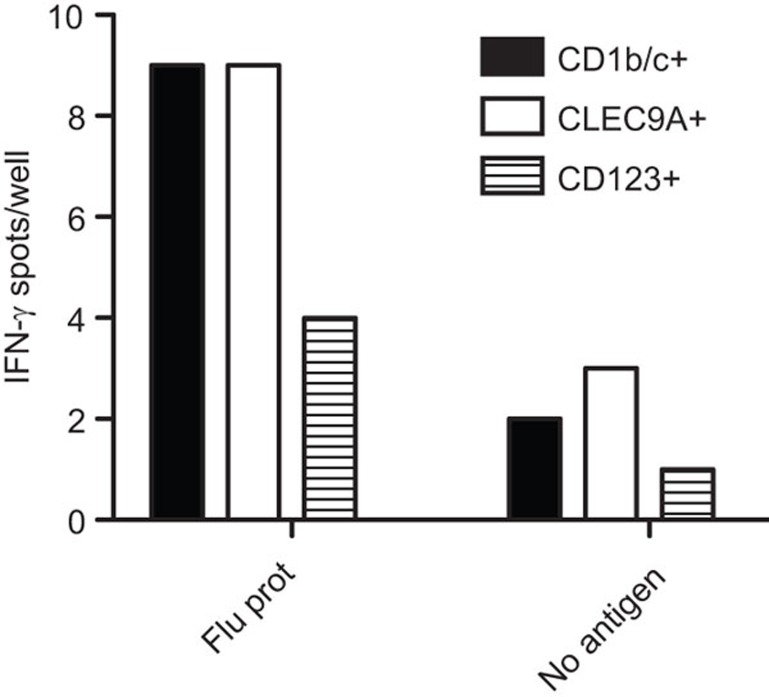

Cross-presentation capacity of Flt3L-derived DCs

Cross-presentation of an exogenous antigen on MHC class I to CD8+ T cells and to induce an antigen specific cytotoxic T-cell response are major functions of DCs, particular during an infection by certain viruses. In C57BL/6 mice, this is a specialized function of splenic and Flt3L-derived CD8+ cDCs.5,7 However, it has been demonstrated recently that both CD1b/c+ and CD141+CLEC9A+ cDCs as well as CD304+ pDCs in both human blood and spleen can cross-present antigen, albeit with different efficiencies.20,21,22,23,24 We therefore tested the ability of Flt3L-derived human DCs to cross-present influenza virus protein to a CD8+ T-cell clone specific for an epitope in the matrix of influenza virus. CD8+ T-cell activation was measured as IFN-γ secretion by ELISpot assay. The CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ cDCs as well as CD123+ pDCs were all capable of inducing IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Activation of CD8+ T cells in a cross-presentation assay. Flt3L-derived CD11c+CD1b/c+, CD11cintCLEC9A+ DCs and CD11c−CD123+ pDCs were isolated, pre-incubated with influenza antigens for 2.5 h (4000 DCs/well, duplicate wells) washed and cocultured with a T-cell clone (10 000 cells/well) containing influenza-specific CD8 T cells over night on an anti-IFN-γ mAb coated ELISpot plate. IFN-γ secretion was detected with a secondary anti-IFN-γ mAb. Data are one representative of four donors with similar results. DC, dendritic cell; Flt3L, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; IFN, interferon; mAb, monoclonal antibody; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell.

Discussion

Since the discovery that DCs are a heterogeneous population of cells in mice,42 the surface phenotype, function and developmental origins of the DC subsets have been the focus of intense research. A number of molecules have been shown to be differentially expressed by the murine cDC subsets including CD8, Sirpα, CD11b, Clec9A and CD24. These markers have been used to segregate DC subsets in the spleen,30,42 the thymus30,42 and in Flt3L cultures in vitro.7 Murine DC subsets also have unique developmental origins and specialized functions reflected in the differential expression of and requirement for transcription factors,33,34,35 expression of TLRs7,36,37 and production of cytokines. In particular, CD8+ DCs compared to the CD8− DCs require IRF8 and Batf3 for development, express TLR3, produce high levels of IL-12p70 and are efficient at cross-presentation of antigen to CD8+ T cells both in vitro and in vivo.5,39,43,44,45 Such properties of this subset have been exploited in in vivo targeting experiments whereby antigens specifically targeted to the CD8+ DC subset boost immune responses and shows promise in improving vaccine delivery and efficacy.16,19,46 The generation of large numbers of DC subset equivalents in vitro from bone marrow precursors in the presence of Flt3L has facilitated further study of mouse DC subsets.7

Recent studies in human blood and spleen have revealed the presence of a number of subsets12,24 that are similar to those found in the mouse with respect to surface phenotype, TLR expression, transcription factor expression and overall transcriptional profile.12,15,22,24 Together, these data have strongly suggested that the CD141+ DCs are similar to the murine CD8+ DCs and CD1b/c+ DCs similar to the CD8− DCs. However, it is clear from these experiments that human cDC subsets share many key functions that in the mouse more clearly distinguish the DC subsets. Both the CD1b/c+ and CD141+ DCs in human blood and spleen have the capacity to produce IL-12p70 and cross-present antigen.21,22,47 The efficiency with which the cDC subsets carry out these two functions appears to be affected by the conditions used in individual assays including the particular antigen used in the cross-presentation assay. It may be a reason why some studies report that the CD141+ DCs are more specialized at cross-presentation20,21,22 whereas others report that CD1b/c+ DCs are more efficient at this process.24 A number of key questions with regard to human DC subset development and function remain, but are difficult to address in vivo and a culture system that can differentiate the three DC subsets under the same conditions would be a useful research tool.

In this study, we utilized a culture system to generate human DCs from CD34+ precursors isolated from G-CSF-mobilized blood in the presence of Flt3L and TPO.

Flt3L is a key cytokine in the development of both murine and human steady-state DC subtypes as demonstrated by the development of DCs in bone marrow cultures after the addition of Flt3L, the increase in number of DCs found in both mice and humans after the injection of Flt3L and the reduced number of DCs found in Flt3L−/− mice.48,49,50,51,52

We now show that in addition to pDCs,26 this culture system also supports the development of both the CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ DCs and CD14+ monocytes. This is in keeping with observations that humans injected with Flt3L show an increase in both DCs and monocytes.53 This is the first time a human culture system has been demonstrated to contain both the conventional DC subsets described in vivo. This culture system did not support the generation of the CD16+ monocyte subset. It is possible that the cytokines required for their development or for the expression of CD16 were not provided in this in vitro system. Furthermore, the CLEC9A+ DCs did not express CD141. This is analogous to the mouse Flt3L culture system where CD8α is not expressed on the cDCs.7 Like the mouse, the lack of expression of CD141 on cDCs suggests that certain cytokines or conditions not provided in the culture system are needed for its upregulation. Nonetheless, CLEC9A and XCR1 represent two molecules that are unique to the CD141+ DCs in human blood and can thus also be used to distinguish this subset.16,17,18,20,21

The CD1b/c+ DC population represented the largest population among the cultured DCs and the CLEC9A+ DCs the smallest. Like the blood, there were a large number of HLA-DR+ Lineage− cells that did not express a DC marker (the DC marker-negative population). These cells most likely represent a precursor population and warrant further investigation.

Similar to human blood, the Flt3L-derived CD1b/c+ DCs expressed SIRPα, CD11b, CD83 and CD86,24 produced IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 in response to stimulation, cross-presented antigen and were the most efficient stimulators of CD4+ T cells in an MLR.24 In addition, they expressed intermediate levels of TLR3, and showed a positive response to Poly(I∶C), a TLR3 agonist, by increasing production of IL-1β, as previously demonstrated.22 However, in contrast to blood CD1b/c+ DCs, cultured CD1b/c+ DCs did not produce high levels of IL-6 or Mip-1α, a difference that may represent their relative immaturity in culture or a lack of a particular stimulus that is present only in vivo.

The Flt3L-derived CD1b/c+ DCs expressed relatively low levels of IRF8, and high levels of IRF4. The requirement for IRF8 in the development of mouse CD8+ cDCs and not the CD8− cDC is clear.34,35 The low levels of IRF8 in CD1b/c+ cDCs in human blood, spleen and Flt3L-derived DCs strongly suggest that this transcription factor is not required for its development. However, Hambleton et al.47 have shown that patients with an autosomal dominant mutation in IRF8 that affects its DNA binding capacity have a marked reduction in the proportion of CD1b/c+ cDCs with no reduction in the proportion of CD141+ cDCs. It could be concluded from these data that IRF8 may indeed have a role in the development of CD1b/c+ cDCs, different from what the expression data in human DCs suggests, and different from what is known in the mouse. While the Flt3L-derived CD1b/c+ cDCs seemed to express higher levels of IRF4, blood and spleen CD1b/c+ DCs express relatively low levels. The function of IRF4 in the CD1b/c+ cDC development would be interesting to dissect, given that it is required for the development of murine CD4+CD8− cDC.34 The culture system described here could be of great use in dissecting the exact requirement for both IRF4 and IRF8 in human DC development.

The Flt3L-derived CLEC9A+ DCs displayed similarities to their in vivo counterparts in their expression of XCR1 and lack of expression of SIRPα, CD11b and CD83. They expressed IRF8 and TLR3, two hallmarks of this subset in blood and spleen,22,23 albeit at lower levels than their in vivo DC counterparts. Furthermore, similar to blood CLEC9A+ cDCs, they stimulated CD4+ T cells to a lesser extent than the CD1b/c+ DCs in an MLR, cross-presented antigen and produced IL-6, TNF-α and Mip-1α. Notably, similar to human blood CLEC9A+ cDCs, in the presence of CD40L, IFN-γ, IL-4 and GM-CSF, they produced only low levels of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70.24 IL-12p70 was enhanced slightly in the presence of Poly(I∶C), but still much lower than secretion by CD1b/c+ DCs. This result is in keeping with a recent study demonstrating that human blood BDCA3+ DCs stimulated with Poly(I∶C) produce only low levels of IL-12p70.54 Furthermore, a recent study on in vitro derived CD141+CLEC9A+ DCs differentiated from HSCs in the presence of a cocktail of cytokines including SCF, Flt3L, IL-3, IL-6, GM-SCF and IL-4 has shown a similar poor response of this population to TLR stimulation with respect to IL-12p70 production.23 They demonstrated that a further stimulus of antigen-specific T cells was required to produce IL-12p70. It may be that the cultured DCs in general, similar to mouse cultured DCs, represent an immature DC subset that requires a number of different stimuli to be fully activated. Indeed, it is known that Flt3L keeps cultured DC in an immature state (Shortman K, personal communication). The nature of the stimuli will need to be further dissected.

The pDCs expressed intermediate levels of SIRPα, and high levels of IRF8, TLR7 and TLR9, as previously shown.26 They responded to CpG by producing IFN-α and IL-6 similar to in vivo human DCs, albeit at lower absolute levels, but did not produce Mip-1α. In addition, they were capable of cross-presenting antigen, but at a lower efficiency than their in vivo counterparts.

A major component of the cultures were the CD14+ monocytes. They expressed intermediate levels of TLR7, and high levels of TLR4 (data not shown). LPS stimulation induced high levels of IL-1β and IL-6 and a suppression of IL-12p70 production, which was similar to what had been described previously.41 A proportion of the CD14+ cells express high levels of HLA-DR and may encompass monocyte-derived DCs. Further study into the function of these cells would be of interest.

Overall, similar to the mouse system, we now have the capacity to generate the CD1b/c+ and CLEC9A+ cDCs, the CD123+ pDCs and the CD14+ monocytes in culture. The DCs display a phenotype that is very similar to their in vivo counterparts. With respect to function, there are key similarities between the cultured and in vivo DCs as described above, but also some differences. With respect to TLR and IRF expression, these differences appear to be largely quantitative rather than qualitative with similar patterns of differences between the cultured DC subsets emerging. Further study on the function of human DC subsets using this system could be achieved and the success of targeting antigens to DCs via cell surface molecules could be safely and routinely tested in vitro.

Ethical considerations

This project was approved by the Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute Research Ethics Committee. The research undertaken here conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

LW is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Research Fellowships. AWR is supported by a Victorian Cancer Agency Fellowship. This work was also funded by an NHMRC Project Grant (LW) and an NHMRC Program Grant (AWR). This work was made possible through Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and Australian Government NHMRC IRIIS. We are grateful to the members of the FACS Laboratory for their excellent assistance with cell sorting. We thank Mireille Lahoud for the antibody against CLEC9A, Gaetano Naselli for advice on the cytokine multiplex assay and Naomi Sprigg for the acquisition of samples for this research.

References

- Kadowaki N, Antonenko S, Liu YJ. Distinct CpG DNA and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid double-stranded RNA, respectively, stimulate CD11c− type 2 dendritic cell precursors and CD11c+ dendritic cells to produce type I IFN. J Immunol. 2001;166:2291–2295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug A, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Jahrsdorfer B, Blackwell S, Ballas ZK, et al. Identification of CpG oligonucleotide sequences with high induction of IFN-alpha/beta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2154–2163. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2154::aid-immu2154>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keeffe M, Hochrein H, Vremec D, Caminschi I, Miller JL, Anders EM, et al. Mouse plasmacytoid cells: long-lived cells, heterogeneous in surface phenotype and function, that differentiate into CD8+ dendritic cells only after microbial stimulus. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1307–1319. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vremec D, Pooley J, Hochrein H, Wu L, Shortman K. CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes in mouse thymus and spleen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2978–2986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K, Heath WR. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietto AI, O'Keeffe M, Gartlan K, Wright MD, Shortman K, Wu L, et al. Differential production of inflammatory chemokines by murine dendritic cell subsets. Immunobiology. 2004;209:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik SH, Proietto AI, Wilson NS, Dakic A, Schnorrer P, Fuchsberger M, et al. Cutting edge: generation of splenic CD8+ and CD8− dendritic cell equivalents in Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand bone marrow cultures. J Immunol. 2005;174:6592–6597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Kilby AW, Kretz CC, Pechhold S, Price JD, Dorta S, Ramos H, et al. Interleukin-2 inhibits FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor ligand (flt3L)-dependent development and function of conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2408–2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009738108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers H, Schnorfeil FM, Brocker T. Differentially expressed microRNAs regulate plasmacytoid vs. conventional dendritic cell development. Mol Immunol. 2010;48:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathaliyawala T, O'Gorman WE, Greter M, Bogunovic M, Konjufca V, Hou ZE, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin controls dendritic cell development downstream of Flt3 ligand signaling. Immunity. 2010;33:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathe P, Pooley J, Vremec D, Mintern J, Jin JO, Wu L, et al. The acquisition of antigen cross-presentation function by newly formed dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5184–5192. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald KP, Munster DJ, Clark GJ, Dzionek A, Schmitz J, Hart DN. Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood. 2002;100:4512–4520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SH, Walzer T, Dembele D, Thibault C, Defays A, Bessou G, et al. Novel insights into the relationships between dendritic cell subsets in human and mouse revealed by genome-wide expression profiling. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R17. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminschi I, Proietto AI, Ahmet F, Kitsoulis S, Shin Teh J, Lo JC, et al. The dendritic cell subtype-restricted C-type lectin Clec9A is a target for vaccine enhancement. Blood. 2008;112:3264–3273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galibert L, Diemer GS, Liu Z, Johnson RS, Smith JL, Walzer T, et al. Nectin-like protein 2 defines a subset of T-cell zone dendritic cells and is a ligand for class-I-restricted T-cell-associated molecule. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21955–21964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huysamen C, Willment JA, Dennehy KM, Brown GD. CLEC9A is a novel activation C-type lectin-like receptor expressed on BDCA3+ dendritic cells and a subset of monocytes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16693–16701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709923200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho D, Mourao-Sa D, Joffre OP, Schulz O, Rogers NC, Pennington DJ, et al. Tumor therapy in mice via antigen targeting to a novel, DC-restricted C-type lectin. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2098–2110. doi: 10.1172/JCI34584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozat K, Guiton R, Contreras V, Feuillet V, Dutertre CA, Ventre E, et al. The XC chemokine receptor 1 is a conserved selective marker of mammalian cells homologous to mouse CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1283–1292. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachem A, Guttler S, Hartung E, Ebstein F, Schaefer M, Tannert A, et al. Superior antigen cross-presentation and XCR1 expression define human CD11c+CD141+ cells as homologues of mouse CD8+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1273–1281. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed SL, Kassianos AJ, McDonald KJ, Clark GJ, Ju X, Angel CE, et al. Human CD141+ (BDCA-3)+ dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1247–1260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin LF, Salio M, Griessinger E, Anjos-Afonso F, Craciun L, Chen JL, et al. Characterization of human DNGR-1+ BDCA3+ leukocytes as putative equivalents of mouse CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1261–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittag D, Proietto AI, Loudovaris T, Mannering SI, Vremec D, Shortman K, et al. Human dendritic cell subsets from spleen and blood are similar in phenotype and function but modified by donor health status. J Immunol. 2011;186:6207–6217. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klechevsky E, Morita R, Liu M, Cao Y, Coquery S, Thompson-Snipes L, et al. Functional specializations of human epidermal Langerhans cells and CD14+ dermal dendritic cells. Immunity. 2008;29:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Antonenko S, Sederstrom JM, Liang X, Chan AS, Kanzler H, et al. Thrombopoietin cooperates with FLT3-ligand in the generation of plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors from human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2004;103:2547–2553. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom B, Ho S, Antonenko S, Liu YJ. Generation of interferon alpha-producing predendritic cell (Pre-DC)2 from human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1785–1796. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratta M, Rondelli D, Fortuna A, Curti A, Fogli M, Fagnoni F, et al. Generation and functional characterization of human dendritic cells derived from CD34 cells mobilized into peripheral blood: comparison with bone marrow CD34+ cells. Br J Haematol. 1998;101:756–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vremec D, Shortman K. Dendritic cell subtypes in mouse lymphoid organs: cross-correlation of surface markers, changes with incubation, and differences among thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1997;159:565–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahoud MH, Proietto AI, Gartlan KH, Kitsoulis S, Curtis J, Wettenhall J, et al. Signal regulatory protein molecules are differentially expressed by CD8− dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:372–382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras V, Urien C, Guiton R, Alexandre Y, Vu Manh TP, Andrieu T, et al. Existence of CD8alpha-like dendritic cells with a conserved functional specialization and a common molecular signature in distant mammalian species. J Immunol. 2010;185:3313–3325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner BG, Dorner MB, Zhou X, Opitz C, Mora A, Guttler S, et al. Selective expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 on cross-presenting dendritic cells determines cooperation with CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Honma K, Matsuyama T, Suzuki K, Toriyama K, Akitoyo I, et al. Critical roles of interferon regulatory factor 4 in CD11bhighCD8alpha− dendritic cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8981–8986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402139101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T, Tailor P, Yamaoka K, Kong HJ, Tsujimura H, O'Shea JJ, et al. IFN regulatory factor-4 and -8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:2573–2581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Sestili P, Borghi P, Venditti M, Morse HC, 3rd, et al. ICSBP is essential for the development of mouse type I interferon-producing cells and for the generation and activation of CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1415–1425. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AD, Diebold SS, Slack EM, Tomizawa H, Hemmi H, Kaisho T, et al. Toll-like receptor expression in murine DC subsets: lack of TLR7 expression by CD8 alpha+ DC correlates with unresponsiveness to imidazoquinolines. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:827–833. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietto AI, Lahoud MH, Wu L. Distinct functional capacities of mouse thymic and splenic dendritic cell populations. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:700–708. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrossay D, Napolitani G, Colonna M, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Specialization and complementarity in microbial molecule recognition by human myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3388–3393. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3388::aid-immu3388>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochrein H, Shortman K, Vremec D, Scott B, Hertzog P, O'Keeffe M. Differential production of IL-12, IFN-alpha, and IFN-gamma by mouse dendritic cell subsets. J Immunol. 2001;166:5448–5455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz O, Edwards AD, Schito M, Aliberti J, Manickasingham S, Sher A, et al. CD40 triggering of heterodimeric IL-12 p70 production by dendritic cells in vivo requires a microbial priming signal. Immunity. 2000;13:453–462. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:942–949. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vremec D, Zorbas M, Scollay R, Saunders DJ, Ardavin CF, Wu L, et al. The surface phenotype of dendritic cells purified from mouse thymus and spleen: investigation of the CD8 expression by a subpopulation of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:47–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Haan JM, Lehar SM, Bevan MJ. CD8+ but not CD8− dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. . J Exp Med. 2000;192:1685–1696. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooley JL, Heath WR, Shortman K. Cutting edge: intravenous soluble antigen is presented to CD4 T cells by CD8− dendritic cells, but cross-presented to CD8 T cells by CD8+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5327–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idoyaga J, Lubkin A, Fiorese C, Lahoud MH, Caminschi I, Huang Y, et al. Comparable T helper 1 (Th1) and CD8 T-cell immunity by targeting HIV gag p24 to CD8 dendritic cells within antibodies to Langerin, DEC205, and Clec9A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2384–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019547108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton S, Salem S, Bustamante J, Bigley V, Boisson-Dupuis S, Azevedo J, et al. IRF8 mutations and human dendritic-cell immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:127–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasel K, de Smedt T, Smith JL, Maliszewski CR. Generation of murine dendritic cells from flt3-ligand-supplemented bone marrow cultures. Blood. 2000;96:3029–3039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakes ML, Lu L, Subbotin VM, Thomson AW. In vivo administration of flt3 ligand markedly stimulates generation of dendritic cell progenitors from mouse liver. J Immunol. 1997;159:4268–4278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, Roux ER, Lyman SD, Shortman K, et al. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1953–1962. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna HJ, Stocking KL, Miller RE, Brasel K, de Smedt T, Maraskovsky E, et al. Mice lacking flt3 ligand have deficient hematopoiesis affecting hematopoietic progenitor cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. Blood. 2000;95:3489–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keeffe M, Hochrein H, Vremec D, Pooley J, Evans R, Woulfe S, et al. Effects of administration of progenipoietin 1, Flt-3 ligand, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and pegylated granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on dendritic cell subsets in mice. Blood. 2002;99:2122–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroquin CE, Westwood JA, Lapointe R, Mixon A, Wunderlich JR, Caron D, et al. Mobilization of dendritic cell precursors in patients with cancer by flt3 ligand allows the generation of higher yields of cultured dendritic cells. J Immunother. 2002;25:278–288. doi: 10.1097/01.CJI.0000016307.48397.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibelt G, Klinkenberg LJ, Cruz LJ, Tacken PJ, Tel J, Kreutz M, et al. The C-type lectin receptor CLEC9A mediates antigen uptake and (cross-)presentation by human blood BDCA3+ myeloid dendritic cells. Blood. 2012;119:2284–2292. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]