Abstract

PQQ is an exogenous, tricyclic, quino-cofactor for a number of bacterial dehydrogenases. The final step of PQQ formation is catalyzed by PqqC, a cofactorless oxidase. This study focuses on the activation of molecular oxygen in an enzyme active site without metal or cofactor and has identified a specific oxygen binding and activating pocket in PqqC. The active site variants H154N, Y175F,S and R179S were studied with the goal of defining the site of O2 binding and activation. Using apo-glucose dehydrogenase to assay for PQQ production, none of the mutants in this “O2 core” are capable of PQQ/PQQH2 formation. Spectrophotometric assays give insight into the incomplete reactions being catalyzed by these mutants. Active site variants Y175F, H154N and R179S form a quinoid intermediate (Figure 1) anaerobically. Y175S is capable of proceeding further from quinoid to quinol, whereas Y175F, H154N and R179S require O2 to produce the quinol species. None of the mutations precludes substrate/product binding or oxygen binding. Assays for the oxidation of PQQH2 to PQQ show that these O2 core mutants are incapable of catalyzing a rate increase over the reaction in buffer. Interestingly, H154N can catalyze the oxidation of PQQH2 to PQQ faster than buffer, but only with H2O2 as an electron acceptor, not with O2. Taken together, these data indicate that none of the targeted mutants can react fully to form quinone even in the presence of bound O2. The data indicate a successful separation of oxidative chemistry from O2 binding. The residues H154, Y175, and R179 are proposed to form a core O2 binding structure that is essential for O2 activation.

Keywords: PqqC, non-metal O2 pocket, redox inactive mutants

Pyrroloquinoline quinone (4,5-dihydro-4,5-dioxo-1H-pyrrolo-[2,3-f]quinoline- 2,7,9-tricarboxylic acid: PQQ (1)) is an aromatic, tricyclic ortho-quinone that serves as a cofactor for a number of prokaryotic dehydrogenases, found largely but not exclusively in Gram-negative bacteria (1–3). The oxidative reactions catalyzed by PQQ-dependent enzymes are focused on catabolic pathways, where the best studied examples are methanol dehydrogenase and glucose dehydrogenase (4). PQQ is part of the quinone family of cofactors and has remarkable antioxidant properties (5–7). Like all known quinone cofactors, PQQ is peptide-derived (6). But unlike the other quinone cofactors, such as topaquinone (TPQ), tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ), lysyl tyrosylquinone (LTQ) and cysteine tryptophylquinone (CTQ) (6, 8, 9), it is freely dissociable from the enzyme and its biogenesis is independent of its catalytic function. The biosynthesis of PQQ is a complex process and in Klebsiella pneumoniae is catalyzed by the gene products of pqqABCDEF (10). All the carbon and nitrogen atoms in PQQ derive from a conserved tyrosine and glutamate in the peptide substrate PqqA (11).

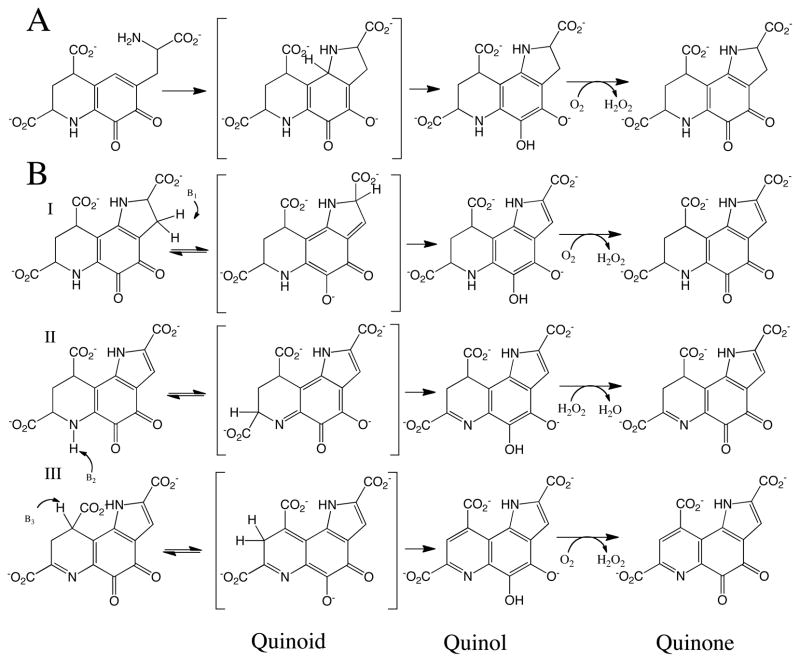

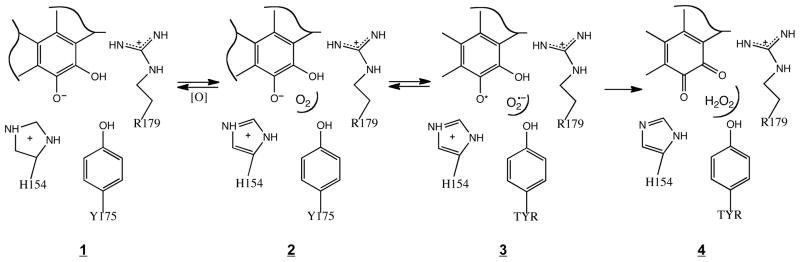

The final step of PQQ formation is catalyzed by PqqC and involves a ring closure and eight-electron oxidation of AHQQ (3a-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)–4,5-dioxo-4,5,6,7,8,9 hexahydroquinoline-7,9-dicarboxylic acid) (Structure 1, Scheme. 1) (12, 13). As shown in Scheme. 1, AHQQ must undergo a two-electron oxidative ring closure (A) followed by three additional two-electron oxidation steps (BI-BIII). Recent X-ray studies of a mutant form of PqqC support ring closure as the initial step in AHQQ oxidation (14), while the order of BI-BIII is currently unknown. The net reaction in Scheme. 1 has been well characterized and occurs via the production of only three moles of hydrogen peroxide (12), implicating bound hydrogen peroxide as the electron acceptor in either steps BI or BII; the biochemical detection of final products, H2O2 and PQQ, during a single turnover of PqqC (12) implicates O2 as electron acceptor in the final product-forming step (BIII). The absence of any requirement for an external cofactor or metal (12) raises the very interesting question regarding how O2 is activated in this metal and cofactor free active site.

Scheme 1.

Overall mechanism proposed for the conversion of AHQQ to PQQ (12). Note the recurring formation of quinoid, quinol, and quinone species. In the case of the quinol, there is spectroscopic evidence for both monoprotic (as shown) and diprotic species.

X-ray crystallographic studies of PqqC have provided a fairly detailed picture of the amino acid side chains positioned near bound PQQ (Figure 1) that are likely to be involved in the postulated base-catalyzed proton abstraction steps (Scheme. 1). According to our working model, base catalysis is a pre-requisite for tautomerization of substrate to a quinoid intermediate, which then aromatizes to yield the individual quinol products of pathways A and BI-BIII. H84 is completely conserved among the sequenced PqqC proteins, and was the subject of an earlier investigation (15). In this instance, mutations in H84 led to the accumulation of quinoid species, not their precursors, revising the role for H84 to that of a proton donor in quinoid formation. We note that the progressive release of protons from the AHQQ substrate and its derived intermediates, together with the requirement for a net uptake of two protons in the reduction of each molecule of oxygen or hydrogen peroxide, requires proton conduction through the active site. This suggests a dual role for active site side chains as base catalysts in substrate oxidation followed by proton donors in hydrogen peroxide formation.

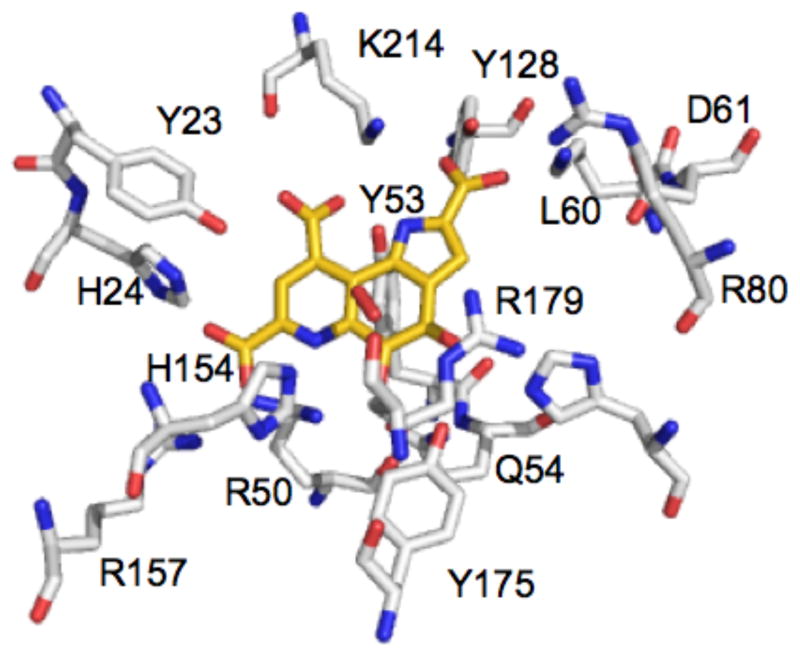

Figure 1.

The active site of PqqC. Residues are shown in white sticks with heteroatoms in blue (N) and red (O), PQQ is shown in gold and the putative oxygen molecule is shown above the PQQ ring in red. (PDB: 1OTW) (12).

In the present study, we have concentrated on defining the site for O2 binding and activation in PqqC. Inspection of the active site of the complex of PqqC and PQQ has indicated electron density above the PQQ ring that is consistent with either O2 or hydrogen peroxide. Three residues are identified within 5 Å of the putative oxygen site (16): Y175, R179 and H154, Figure 2. The τ-N of H154 is at 3.3 Å from O1 of the species bound above PQQ, while ε-N of R179 is 2.9 Å away. Both Y175 and R179 are completely conserved in PqqC, whereas, H154 is highly conserved with a glutamine occurring rarely at this position, for example, in enzyme from proteobacterium Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum (protein ID ZP 00052131), and from the gram-positive bacterium Desulfitobacterium hafniense (protein ID ZP 00101389) (RoseFigura and Klinman, in preparation). The three residues - H154, Y175 and R179 - will, heretofore, be referred to as the putative “O2-binding core”. In contrast to H84, these residues move into the active site following the conformational change that occurs at helices 5 and 6 upon binding of PQQ to PqqC (12). H154, located on helix 5, and Y175 and R179, on helix 6, are fully solvent-exposed prior to the addition of PQQ to PqqC.

Figure 2.

A. Distances in the PqqC active site for core residues (Y175, H154, R179). PQQ is shown in gold with the putative oxygen molecule in red over the quinone ring. Active-site residues H84, H154, Y175 and R179 are shown in green. B. Space filling model for Y175, H154 and R179, as well as the putative O2 (purple) above the PQQ ring (gold). (PDB: 1OTW) (12).

An X-ray structural analysis of PqqC mutants has recently been published (14). These structures indicate that mutants H154S and Y175F have different effects on the structure of the enzyme/product complexes. H154S/PQQ is unable to form the closed complex, whereas the Y175F/PQQ structure is closed and closely resembles WT, with an observable electron density over the quinone ring. Herein, we describe the kinetics of the reaction of four active site mutants (H154N,1 Y175F, Y175S, R179S) under single turnover conditions that permit the detection of spectroscopic intermediates and their comparison to the wild-type enzyme. The aberrant kinetic behavior found with all four mutants, together with biochemical analyses of product formation, directly links their presence in the active site to the binding and subsequent activation of O2.

Materials and Methods

Chemical and Molecular Biological Reagents

Buffers, salts, general reagents, and culture media were obtained from Sigma and Fisher and were of the highest available purity. Ni-nitriloacetic acid (NTA) resin, DNA purification kits, and PCR primers were purchased from Qiagen. Enzymes and reagents for mutagenesis reactions were from Strategene. PQQ was purchased from Fluka. Restriction enzymes and appropriate reaction buffers were purchased from New England Biolabs. Cell lines were obtained from Invitrogen. AHQQ was purified from a pqqC mutant strain EMS12 of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 as described. Concentration of AHQQ was determined spectrophotometrically at pH 7 by averaging the concentrations determined at three wavelengths with the following extinction coefficients: 222 nm = 15.7 mM−1 cm−1, 274 nm = 8.26 mM−1 cm−1, and 532 nm = 2.01 mM−1 cm−1. Plasmids were developed in the Schwarzenbacher lab and made from genomic DNA from Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78578 (WT2). Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78578 PqqC varies from the previously described wild-type (WT1) PqqC at the base of the 3rd alpha helix. There are three differences between the two sequences: A21D, D37N and K41E, with WT1 listed first. The A21D variant was obvious in the original crystal structure, with the further changes at positions 37 and 41 in agreement with the sequence deposited by Postma (PubMed accession number: X58778) (17, 18). Since PqqC from Klebsiella sub-species MGH 78578 forms PQQ at close to the same rate as WT 2, we have used these two parent enzymes from K. pneumoniae sub-species interchangeably.

PCR Cloning, Expression and Purification of PqqC

PCR cloning was performed by Sandra Puehringer of the Schwarzenbacher group (University of Salzburg). Plasmids were constructed in pET29 with kanamycin resistance and a C-terminal His tag. The isolated plasmids were sequenced from both directions using the T7 promoter and terminator primers.

Expression of plasmids was done using BL21(DE3) cells in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Cultures were grown at 37 °C to an optical density at 600 nm of ~ 0.8, at which time, isopropyl B-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM) was added, and the cells harvested ~ 4 h later. All pET-29b-pqqC/D plasmids produced high quantities of protein as judged by SDS-PAGE analysis. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM KH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF and 5 mM MgCl2. After sonication and centrifugation, as described previously (15), the clear supernatant was applied to a 10 mL Ni-NTA column that had been equilibrated in 20 mM Tris buffer supplemented with 300 mM NaCl and 5 mM imidazole. After two buffer washes with increasing amounts of imidazole (5mM and 10mM) the His-tagged bound protein was eluted with 25 mM tris buffer supplemented with 300 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole. Fractions containing mutant enzyme were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, pooled, concentrated and buffer exchanged into 100mM monobasic potassium phosphate pH 8.0 before being aliquoted and snap-frozen. Further column chromatography only provided inactive enzyme, unlike what was seen in the WT1, WT2 and H84 variants, which were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography. A single band was seen on an SDS-PAGE gel, and the Ni-NTA column chromatography provided enzyme with greater than 90% purity. The expression for these mutants was lower than WT and yielded ~ 3 mg/L of culture.

Single Turnover Kinetics

The enzyme in the highest concentration possible without precipitation (WT: 104 μM; Y175F: 27μM; Y175S: 55μM; H154N: 25μM; R179S: 30μM) was mixed with substrate, AHQQ (12μM final concentration), in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, in a total volume of 100 μL. The use of different concentrations for the mutant enzyme forms resulted from their differential solubilities in the μM range; in all instances, final enzyme concentrations were higher than substrate. The enzyme mixture was transferred to a microcuvette, and UV-vis spectra were recorded within 10 sec of addition of AHQQ. Spectra were obtained on a Cary spectrophotometer, and the temperature of the reaction was maintained at 25 °C using a circulating water bath. Spectra were acquired at predetermined time points and the data exported to SPECFIT/32 for analysis. Because of a small amount of protein precipitation during the course of the reaction, all spectra were normalized via a baseline correction (19). Epsilon values and rates were obtained via SpecFit after fitting the spectra to an appropriate kinetic reaction. For spectra where two species built up concurrently, as in all aerobic spectra, the λmax for the peaks were found in SpecFit (at ca. 315 nm and 356 nm).

Anaerobic reactions were done under the conditions described above. Enzyme and substrate were made anaerobic by repeated cycles of argon purging and high-vacuum evacuation on a Schlenk line. The sealed samples were brought into an anaerobic chamber, the protein was transferred into a microcuvette fitted with a rubber stopper, and the substrate was loaded into a syringe and the needle inserted through the stopper and into the top of the cuvette. The cuvette, with the syringe attached, was brought out to the spectrophotometer, and the substrate was mixed thoroughly with enzyme before spectra were recorded. After some time, when no further changes were observed in the UV-vis spectrum of the samples, the stopper was removed and air was blown over the surface of the sample for a few seconds, demonstrating further reaction in some cases.

PQQ Binding

PQQ binding was investigated spectroscopically. One equivalent of PQQ was added to enzyme in 100 mM potassium phosphate at pH 8.0. For binding of reduced PQQ (PQQH2) to WT enzyme, 30 equivalents of dithiothreitol was included in the PQQ solution. All mutants showed absorbance characteristic of a single species by UV/vis spectroscopy.

KD values were acquired fluorometrically as previously described (15). Data were fitted using Kaleidagraph to a quadratic-binding isotherm (eq 1), where ΔF equals the change in fluorescence in a given sample compared to free ligand, ΔFM is the change in fluorescence at saturation, [E]T equals the total concentration of enzyme in each sample, [L]T equals the concentration of total ligand and KD is the dissociation constant of the enzyme-ligand complex (eq 1):

| (1) |

Some mutants, namely Y175F and R179S, did not yield a fluorometric change in the presence of PQQ. Since evidence from both X-ray crystallography (14) and UV/vis spectroscopy shows that PQQ binds to these mutant forms of enzyme, this result is attributed to the absence of a specific interaction(s) necessary for the fluorescence increase normally seen upon PQQ binding to PqqC. Determination of the binding constant of PQQH2 to WT was achieved by shortening the incubation time after the addition of enzyme to five minutes, to avoid reoxidation of PQQH2 to PQQ.

Expression and Purification of Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH)

The apo-form of GDH was expressed and purified with a modification from literature procedures (20). Instead of using a fermentor, overnight cultures (18 L) in shaker flasks, were employed. Cells (~ 80 g) were disrupted by sonication in 250 mL of 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.5, 0.2 M NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 1000 U benzonase. After centrifugation, the clear supernatant was dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 3 mM CaCl2 (GDH Buffer). The dialysate was passed through an SP-Sepharose column (2.5 × 30 cm) and after a buffer wash, GDH was eluted with a NaCl gradient (0–450 mM) in GDH Buffer. Fractions containing GDH were assayed as described elsewhere (20), pooled based on enzyme activity and concentrated to ~ 20 mL. Tris buffer, pH 7.5, was added to a final concentration of 0.1 M and solid (NH4)2SO4 to a final concentration of 1M and the protein solution was passed over a Phenyl-Sepharose column (1.5 × 20 cm). The protein was eluted by a gradient (500 mL) of decreasing concentration of (NH4)2SO4 (1 M to 0). Enzyme containing fractions based on activity assays were combined and dialyzed against GDH Buffer overnight. The purified protein was concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon YM10), frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. This procedure yielded a single band on a gel and gave ~ 20 mg of protein with specific activity of ~ 7000 U/mg, which is comparable to that reported in the literature.

GDH Assay

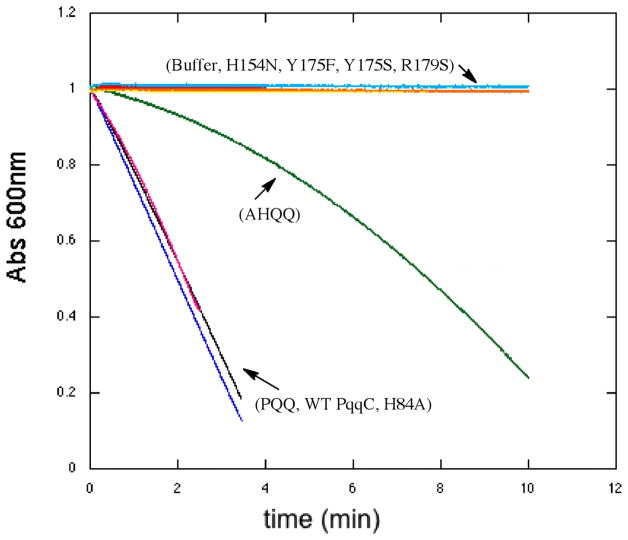

This was carried out to quantify product PQQ production from AHQQ. After aerobic reaction of PqqC (25 μM) and AHQQ (20 μM) in 100 mM KPi, pH 8.0, for 1 h, the assay mixture was taken into an anaerobic chamber, where enzymes samples were denatured with acid. Denaturation in the absence of O2 was necessary to prevent non-enzymatic formation of AHQQ-derived quinones from reaction intermediates, after centrifugation and adjustment of the pH back to pH 8, the resulting supernatants were incubated with GDH anaerobically. Following this incubation, the GDH-bound PqqC products were removed from the anaerobic chamber and assayed for glucose oxidation as previously published (4). This end point assay looks at the amount of PQQ formed after 1 h of reaction of PqqC with AHQQ; all enzymes examined showed a spectroscopic endpoint within this time frame. The amount of PQQ formed from PqqC catalysis can be inferred from the rate of DCIP reduction catalyzed by GDH, which is monitored via a decrease in the absorbance at 600 nm. GDH reactions were run for 30 min or until no further change was observed; the initial point of each reaction was normalized to one.

Quinol Oxidation Assays

To directly test and compare the ability of the WT and mutant enzymes to do oxidative chemistry 20 μM PQQ was anaerobically reduced using 1.25 equivalents of dithiothreitol (25 μM). This reduced quinol was then bound to 25 μM PqqC enzyme anaerobically in 100 mM KPi, pH 8.0, and sealed in a cuvette. This anaerobic cuvette was taken out of the anaerobic chamber and exposed to oxygen approximately 10 sec before starting spectroscopic scans. Free reduced PQQ has an absorbance at 308 nm, which generally shifts to 315–318 nm when the chromophore is bound to PqqC. The spectral traces were analyzed with the program SpecFit. The data were baseline-corrected at 800nm and then fitted to a single exponential to find the rate of oxidation of quinol to quinone.

When H2O2 was tested as an oxidant instead of O2, the anaerobic cuvette remained sealed and a gastight syringe was preloaded with H2O2 in an anaerobic chamber. H2O2 (final concentration of 25 μM) was added to the quinol sample directly before spectra were collected. Spectral traces were analyzed by the same method as the O2-dependent reoxidation spectral traces. A 10-fold higher concentration of H2O2 was tested and denatured the enzyme in all cases.

Results

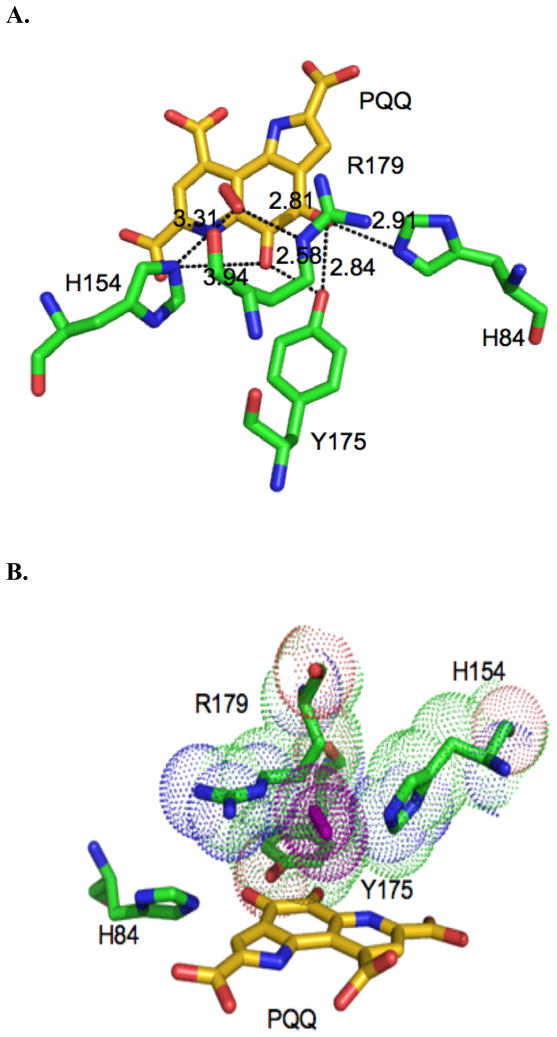

Anaerobic Single Turnover Kinetics of H154N, Y175F, R179S and Y175S

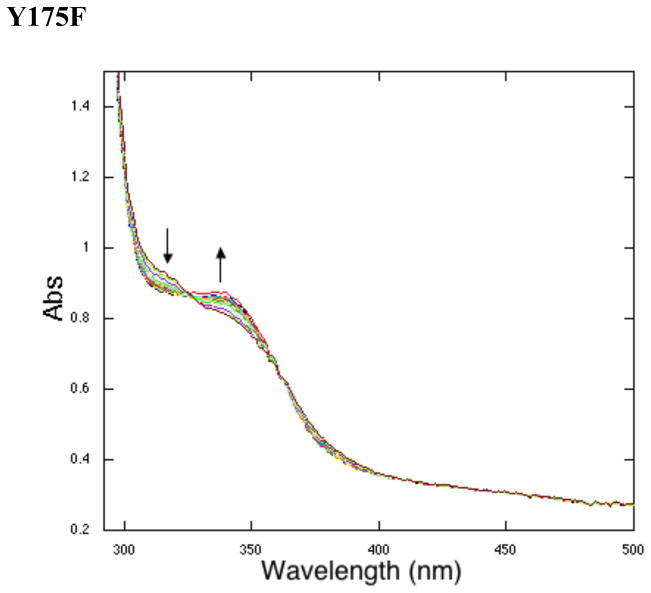

Under anaerobic conditions, the initial steps of the PQQ reaction (Scheme. 1) were probed by UV/vis for comparison to WT enzyme. Representative time courses for reactions initiated by addition of AHQQ are illustrated in Figure 3 for Y175F. Similar time traces were observed for H154N and R179S, and data for all mutants are tabulated in Table 1 in comparison to WT-enzyme. In each case, there is evidence for formation of a species at ca. 340 nm, which in a single instance (Y175S, Figure 3B) proceeds further to a new species at 318 nm. From earlier studies, a 338 nm species was attributed to quinoid (21), while the neutral (protonated) quinol has been assigned to the 318 nm species (22). Unexpectedly, these data suggest that, except for Y175S, mutants have lost their ability to convert the quinoid intermediate to quinol anaerobically, despite the fact that this chemical conversion is a non-oxidative one.

Figure 3.

Single turnover reactions under anaerobic conditions. The apparent absence of the initial enzyme-AHQQ complex at 532 nm is a result of its low extinction coefficient. A. Active site variant Y175F. Representative spectra at time points: 0.2, 0.8, 1.6, 2.4, 4, 5.6, 7.2, 8.8, 10.4, 12, 14.4, 19.5, 25.5, 31.5, 37.5, 43.5, 49.5, 55.5, and 59.5 min. B. Active site variant Y175S. Representative spectra at time points: 0.2, 1.3, 3, 4.3, 8.3, 11, 13.6, 19, 21.6, 27, 31, 35, 39, 43, 47, 51, 55, 59 min.

Table 1.

Anaerobic spectroscopic analysis of PqqC mutants.

| Species | λmax (nm) | ε (mM−1 cm−1) | Rate of formation (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT15 | |||

| WT-AHQQ | 536 | 2.1 | |

| WT-IA1 | 318 | 22 | 2.42 (± 0.07) |

| WT-IA2 | 356 | 12 | 1.22 (± 0.06) |

|

| |||

| H154N | |||

| H154N-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| H154N-IA | 338 | 6.6 | 2.22 × 10−2 (± 0.62) |

|

| |||

| Y175F | |||

| Y175F-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| Y175F-IA | 338 | 7.6 | 6.94 × 10−2 (± 0.40) |

|

| |||

| Y175S | |||

| Y175S-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| Y175S-IA1 | 344 | 6.2 | 7.7 × 10−2 (± 0.3) |

| Y175S-IB | 318 | 8.5 | 2.3 × 10−2 (± 0.2) |

|

| |||

| R179S | |||

| R179S-AHQQ | 532 | 2.2 | |

| R179S-IA | 338 | 7.9 | 3.34 × 10−2 (± 0.79) |

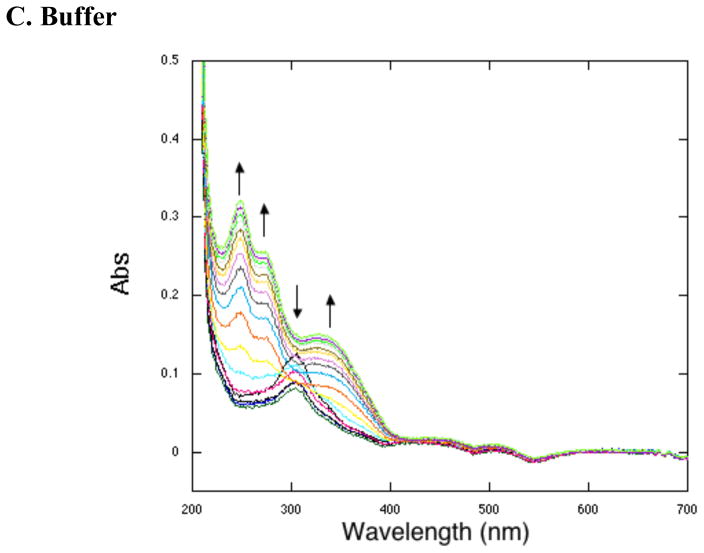

The anaerobic reactions were then exposed to air and the resulting spectra recorded. Under these conditions, a clear 318 nm species forms from the 338nm species for H154N and Y175F (see Figure 4 for an illustrative trace). The R179S variant was found to be unstable under these conditions. Previous work done on WT PqqC showed that anaerobic reactions form quinol intermediates that proceed to PQQ upon the addition of oxygen (15). Characterization of PqqC/PQQ complexes for H154N and Y175S indicates an affinity of PQQ to these mutants that brackets the affinity of PQQ to WT: the KD’s for H154N and Y175S are 0.66 nM and 12.3 nM in relation to a previously determined value of 2.0 nM for WT (15). The absorbance for mutant PQQ complexes is summarized in Table 2 and, in each case, is distinct from 318 nm. Thus, while the kinetic trace in Figure 4 shows that O2 is binding to Y175F (with similar behavior for H154N), and that this binding is required for conversion of a quinoid to quinol intermediate, the data do not directly support any oxidative chemistry in the presence of O2.

Figure 4.

Anaerobic to aerobic transitions. The 338 nm peak decreases as the 318 nm peak increases. The Y175F data shown here is representative of the H154N reaction. Representative spectra at time points: 0.2, 0.6, 1.2, 1.8, 3, 4.2, 5.4, 6.6, 7.8, 9, 10.2, 11.4, 12.6, 13.8, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30 min.

Table 2.

Aerobic spectroscopic analysis of PqqC mutants.

| Species | λmax (nm) | ε (mM−1 cm−1) | Rate of formation (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT15 | |||

| WT-AHQQ | 536 | 2.0 | |

| WT-I | 316 | 23 | 0.960 (± 0.013) |

| WT-PQQ | 346, 498 | 12, 0.6 | 0.340 (± 0.005) |

|

| |||

| H154N | |||

| H154N-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| H154N-IA1 | 315a | 10.1 × 10−2 (± 0.6) | |

| H154N-IA2 | 360a | 10.2 × 10−2 (± 0.5) | |

| H154N-PQQ | 344 | ||

|

| |||

| Y175F | |||

| Y175F-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| Y175F-IA1 | 318a | 14.4 × 10−2 (± 0. 2) | |

| Y175F-IA2 | 356a | 6.6 × 10−2 (± 0.2) | |

| Y175F-PQQ | 342 | ||

|

| |||

| Y175S | |||

| Y175S-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| Y175S-IA | 344 | 2.3 | 27 × 10−2 (± 0.2) |

| Y175S-IB | 318a | 7.6 × 10−2 (± 0.3) | |

| Y175S-IC1 | 356a | 2.2 × 10−2 (± 0.3) | |

| Y175S-PQQ | 344 | ||

|

| |||

| R179S | |||

| R179S-AHQQ | 532 | 2.1 | |

| R179S-IA1 | 318a | 5.67 × 10−2 (± 0.08) | |

| R179S-IA2 | 356a | 6.5 × 10−2 (± 0.1) | |

| R179S-PQQ | 344 | ||

No effort has been made to estimate individual extinction coefficients in the instance where two species form in parallel with similar rate constants.

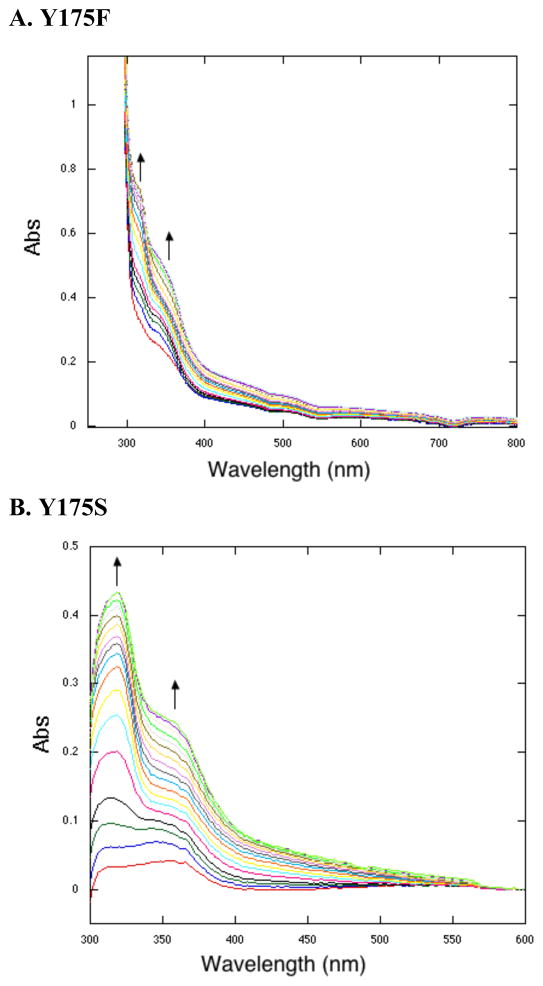

Aerobic Single Turnover Kinetics of H154N, Y175F, R179S and Y175S

The addition of the substrate, AHQQ, and O2 to H154N, Y175F, and R179S, leads to spectra very similar to that of WT PqqC reacted anaerobically (15). As shown for Y175F (Figure 5A), two species form independently, 318 nm and the other, more slowly, at 356 nm. Unlike WT enzyme, the species from Y175F persist in an aerobic environment up to 3 h (data not shown). These intermediates are thought to both be quinols, with one intermediate being the monoprotonated, anionic quinol (356 nm) and the other corresponding to the diprotonated quinol (318 nm) (15). R179S (Table 2) forms the same species as Y175F aerobically, and H154N forms similar species, but with slightly shifted λmax values at 315 nm and 360 nm (Table 2), suggesting subtle differences in charge stabilization of electronically excited states in the H154N variant.

Figure 5.

Single turnover reactions under aerobic conditions. A. Y175F spectra are similar to that of H15N and R179S. Representative spectra at time points: 0.2, 0.8, 1.6, 2.4, 3.2, 4, 6.4, 8, 9.6, 12, 14.4, 19.5, 25.5, 33.5, 41.5, 47.5, 55.5 and 59.5 min. B. Y175S. Representative spectra at time points: 0.2, 1.3, 3, 4.3, 8.3, 11, 13.6, 17.6, 19, 21.6, 27, 31, 35, 39, 43, 47, 51, 55, 57.6 and 59 min.

The spectral species from Y175S, both anaerobically (Figure 3B) and aerobically (Figure 5B), are distinct from intermediates seen with the other three active site variants in several ways. First, a quinol is seen anaerobically (318 nm species, Table 1) while a quinoid intermediate is seen aerobically (344 nm species, Table 2). The detection of additional species with Y175S allows both of their rates of formation to be compared in the absence versus presence of O2. In the case of H154N, Y175F, and R179S, the failure to see any quinoid intermediate aerobically implies a very large rate acceleration by O2 in its breakdown to quinol. As a consequence, the measured rates in the presence of O2 are for quinoid formation, and these can be seen to be enhanced only 2- to 5-fold. Overall, all of the mutants catalyze the formation of quinoid at rates within a factor of 4-fold of one another (either with or without O2). It is Y175S that stands out, with its ability to form a quinol slowly in the absence of O2 and its failure to undergo a large rate acceleration for quinol formation by O2 binding. It appears that, with the exception of Y175S, O2 is necessary to restructure the active site in a way that is essential for a base-catalyzed aromatization coupled to protonation of the quinoid intermediate. Previous work with the PqqC variants of H84 also showed inhibition of the quinoid to quinol conversion anaerobically (15) attributed, in that case, to the absence of a proton donor to neutralize the intermediate quinoid anion that is a prerequisite for quinol production. It should be emphasized that unlike the present studies, H84 mutants were able to catalyze PQQ formation aerobically.

GDH Assay for PQQ Production

Although the spectroscopic analyses summarized above all point toward the failure of the O2 core mutants to produce PQQ, the repeated observation of an absorbance band at 318 nm could have implicated formation of reduced PQQ (PQQH2) that was unable to undergo further oxidation, i.e the final step of BIII in Figure 1. While reduced PQQ bound to PqqC has an absorbance at 318 nm (Figure 8A), previous anaerobic studies with WT PqqC also showed a 318 nm peak that could not be PQQH2, due to the absence of oxygen (15), and which was attributed to the first formed quinol species (Scheme. 1). The ability to reconstitute GDH activity, subsequent to the destructive release of mutant-derived PqqC bound intermediates, was undertaken to test whether the 318nm species seen is PQQH2. It is expected that PQQH2 will either bind directly to GDH or undergo oxidation in solution to PQQ and then add to the GDH (20). As shown in Figure 6, incubation of GDH with either a PQQ standard or product produced by an equivalent amount of WT PqqC or its H84A mutant give similar levels for GDH activity. Previous work has indicated that WT and H84A form PQQ at very different rates but, since the experiments run here are endpoint assays, it is not surprising that the final concentration of PQQ detected is similar. We have shown additionally that pre-binding of GDH with chemically reduced PQQ (PQQH2) gives a turnover rate that is ca. 50 % of GDH reconstituted with PQQ (data not shown). Turning to the O2 core mutants, in no instance are these capable of producing a species that can support GDH-dependent turnover. This contrasts with incubation of AHQQ alone, which is capable either on its own (15) or subsequent to non-enzymatic breakdown, to act as a cofactor for GDH. This indicates that the products of the O2 core mutants are distinct from AHQQ and PQQ/PQQH2 in a manner that prevents their ability to restore activity to apo-GDH when incubated with GDH anaerobically. Future work will focus on the chemical structures of the mutant-derived products.

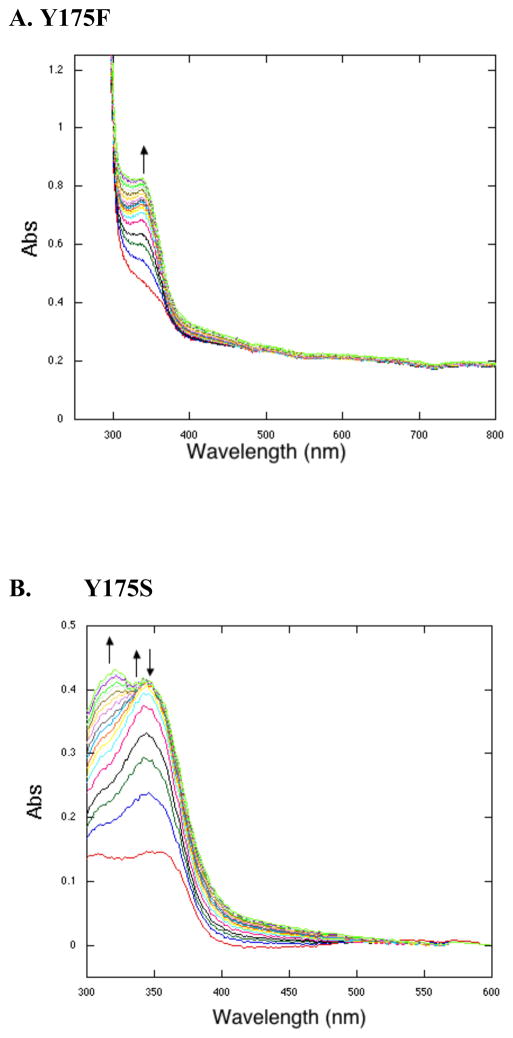

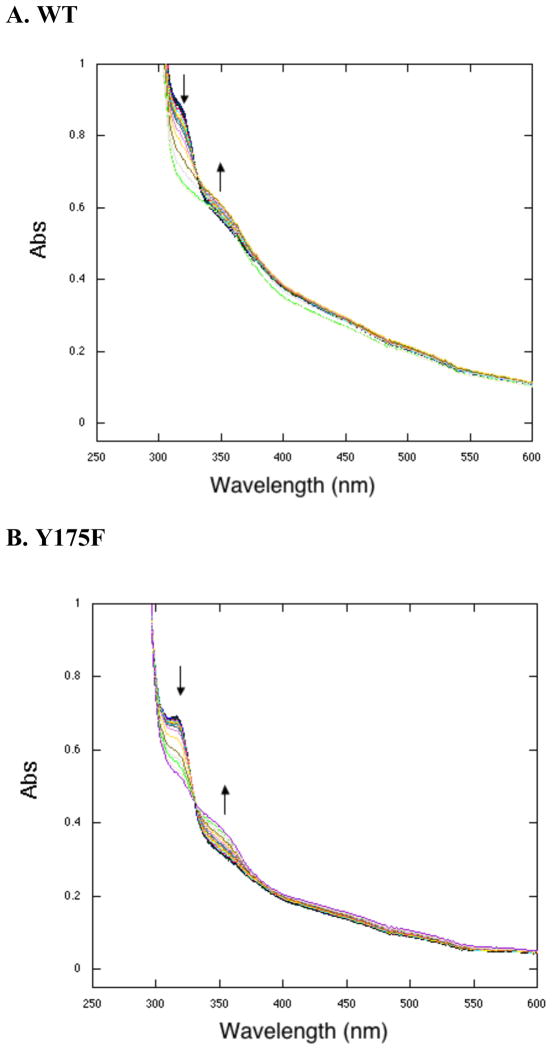

Figure 8.

PQQH2 reoxidation to PQQ in the presence of WT protein (A) and representative O2 core mutant Y175F (B) or buffer (C).

Figure 6.

Reconstitution of GDH with PQQ versus mutant PqqC-generated intermediates. Assays for glucose oxidation products (at 600 nm) are compared using a PQQ standard, WT, H84A, H154N, Y175F, Y175S and R179S (25μM) with AHQQ (20μM). The incubation of AHQQ with GDH shows that the substrate itself can serve as a cofactor.

PQQH2 Reoxidation

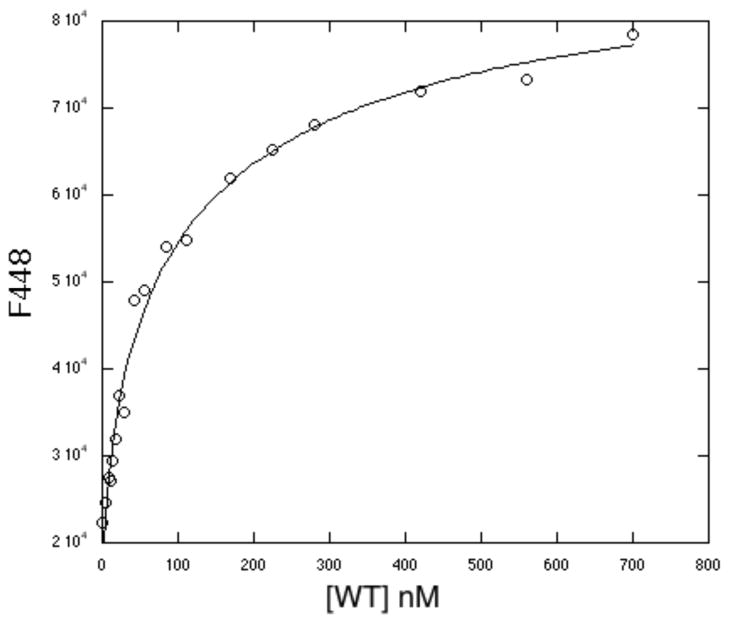

To test the ability of the O2 core mutants of PqqC to do any oxidative chemistry, it was decided to simplify reaction conditions and to examine the last step of the reaction in which product PQQH2 is converted to PQQ. WT-PqqC is found to bind PQQH2 with a KD = 114 nM, Figure 7, less tightly than for PQQ (KD = 2.0 nM) (15), but still stoichiometric under the conditions of these experiments (reoxidation assays were run at 20 μM PQQH2 with 25 μM enzyme). PQQH2 was first incubated with the targeted enzyme anaerobically, and then exposed to air (Representative spectra Figure 8A and B). Quinols are known to reoxidize to quinones in buffer in the presence of air and a control in the absence of protein is given in Figure 8C. Whereas, the solution reaction does not show a straightforward precursor/product relationship, the enzymatic data all show a clean conversion from PQQH2 to PQQ. Noting that the non-enzymatic mechanism of PQQH2 oxidation is more complex than on the enzyme, in no instance do the mutant PqqCs show significant rate acceleration relative to buffer. Despite this lack of detectable rate enhancement, the enzymatic and buffer reactions are clearly occurring along different pathways, showing that enzymatic catalysis does take place, albeit slowly.

Figure 7.

Binding of PQQH2 to WT enzyme as determined by fluorescence spectroscopy.

On the premise that an enzyme-based reduction of H2O2 could occur more facilely than reduction of O2 (23), we next tested H2O2 as the oxidant for the WT PqqC and the O2 core variants. In this instance, the rate for quinol reoxidation by WT PqqC with H2O2 is lowered, consistent with the expectation that O2 is the normal oxidant during the final step of catalysis (BIII in Scheme. 1). Of interest, the mutant H154N begins to approach the rate of the WT with H2O2, undergoing a clear-cut shift in mechanism toward the utilization of this alternate oxidant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rates of PQQH2 reoxidation to PQQ in the presence of O2 and H2O2.

| Enzyme | O2 k1(min−1) | H2O2 k1(min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 2.12 (± 0.97) | 0.646 (± 0.387) |

| H154N | 0.120 (± 0.089) | 0.308 (± 0.009) |

| Y175F | 0.115 (± 0.099) | 0.095 (± 0.015) |

| Y175S | 0.097 (± 0.076) | 0.010 (± 0.006) |

| Buffer | 0.071 (± 0.005) | - |

Discussion

Absence of O2 reactivity

Among the four mutants studied herein, only one has been studied by X-ray crystallography (Y175F), showing a structure in the presence of PQQ very similar to the WT PqqC/PQQ structure, i.e. in a closed conformation. Since H154N shows a KD value for PQQ binding that is similar to WT, and the kinetic traces for H154N and R179S are similar to Y175F, it is reasonable to proceed on the assumption of closed structures for the initial enzyme-AHQQ complexes. However, the behavior of Y175S is sufficiently different from that of the other mutants to suggest an open or partially closed conformation. What is striking about this variant, in relation to the other mutants, is its relative independence of O2 in the quinoid to quinol conversion. A recently solved X-ray structure for a double mutant of PqqC, Y175S/R179S, indicated an open conformation, in which the initial ring cyclization of AHQQ could occur (A in Scheme. 1), but was unable to proceed further toward PQQ (14).

When reacted anaerobically, WT-PqqC catalyzes formation of the initial quinol intermediate (Scheme. 1), with subsequent addition of O2 leading to PQQ. The first unexpected result with the O2 core mutants is the arrest (with the exception of Y175S) of the reaction course at the quinoid stage, indicating a role for O2 binding in facilitating the first base-catalyzed aromatization that generates quinol from quinoid (Scheme. 1). It appears, while the introduction of Y175F, H154N or R179S precludes an anaerobic transition of quinoid to quinol; O2 binding to these proteins is able to “correct” active site defects to allow quinol production. Given the requirement for a properly positioned donor (H84) for quinol formation (15), we suggest that the orientation of H84 may be altered by mutation at H154, Y175 and R179 (cf. Figure 2), and further, that binding of O2 facilitates realignment of H84 into a catalytically suitable position. The second unexpected result is that mutations in the O2 core disable PqqC from doing oxidative chemistry and ultimately forming PQQ. In all instances, the product of the aerobic reaction of these mutations is spectroscopically different from that of genuine PQQ bound to the mutant enzymes (Table 2). When AHQQ is added to enzyme aerobically we see the build up of two peaks at approximately 318 nm and 356 nm (Figure 5). These peaks persist for hours showing insensitivity to an aerobic environment, and are very similar to that observed with WT PqqC reacted anaerobically. The peaks at 318 nm and 356 nm have previously been described as the diprotonated and monoprotonated quinols, respectively (15). The data, thus, indicate that while O2 binds to protein, the mutants are prevented from either facilitating/stabilizing the postulated superoxide anion intermediate (3 in Scheme 2) or promoting the proton transfers necessary for production of hydrogen peroxide (4 in Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Proposed oxidation mechanism of PqqC that involves O2 binding at a pocket created by the “O2 core” amino acids, followed by a series of electron- and proton-coupled/electron transfer steps to generate quinone and bound hydrogen peroxide.

While the spectroscopic traces of these reactions give strong evidence that mutations in the O2 core of PqqC stop formation of PQQ, additional assays were undertaken to support this claim. Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) uses PQQ as an obligate cofactor and provides an assay for PQQ production. As shown in Figure 6, similar activity was seen in the presence of a PQQ standard (20 μM) or the product formed from 20 μM of AHQQ incubated with a 1.25 excess of either the WT PqqC or the H84A variant. The slightly reduced GDH activity in the latter two examples is attributed to some loss of PQQ during enzyme denaturation. By contrast, addition of either buffer or the products of the O2 core mutant reactions (that of H154N, Y175F, Y175S and R179S) gave no indication of species capable of acting as a cofactor for GDH. Surprisingly, the substrate for the PqqC reaction, AHQQ, was able to reconstitute GDH activity, though at a rate lower than that of PQQ. AHQQ is an unstable compound having a half-life of approximately 2 h at pH 6 and room temperature, and we attribute this behavior to likely degradation of AHQQ. Denaturation of the O2 core mutants aerobically did give low level reaction with GDH (results not shown), which we attribute to some oxidation of the AHQQ-derived intermediates, subsequent to release from PqqC and prior to binding to GDH. Controls, in which PQQH2 was used to reconstitute GDH, indicated the ability of reduced cofactor to support enzyme turnover. These data provide corroborative evidence for the proposal that O2 core mutations form a species that is distinct from AHQQ and is neither PQQ nor PQQH2.

The ability of the O2 core mutant enzymes to do oxidative chemistry was further tested, by examining their catalysis of PQQH2 oxidation to PQQ, the last step of BIII in Scheme 1. The nM KD for binding of PQQH2 of PQQ to WT-PqqC (Figure 7), together with the similarity of the KD for PQQ binding to mutants and WT, indicated that PQQH2 should be fully bound under the conditions of these experiments. While the O2 core mutants showed a single isosbestic point for PQQ production from PQQH2 (cf. Figure 8B for Y175F), the rates are low and within error of the formation of PQQ in buffer (Table 3). The fact that the use of hydrogen peroxide as an oxidant, instead of molecular oxygen, both decreased the rate for WT-PqqC and increased that for H154N is of considerable interest, supporting O2 as the natural oxidant in the final step. Clearly, while the H154N lacks the catalytic machinery to activate O2, the presence of Y175 and R179 appears sufficient to permit the thermodynamically more favorable peroxide-based oxidation to proceed (23, 24).

Relationship of PqqC Activation of O2 to Other Oxidases

In aggregate, the data from this work have led to the identification of three protein side chains in PqqC that enable O2 to bind and catalyze the oxidation of intermediate quinols to quinones, Schemes 1 and 2. Historically, most of the mechanistic study of O2 activating enzymes has focused on either metalloenzymes or enzymes that use organic redox cofactors (24, 25). Proteins generally cannot modulate redox potentials sufficiently to activate O2 using the 20 naturally occurring amino acids. A possible mechanism for O2 reduction by WT-PqqC, Scheme 2, shows an anticipated role of electrostatic interactions in the initial formation of O2−, together with the requirement for two protons within each step of the mechanism. While one proton can be provided by the quinol itself, presumably from H84 initially (15), the second proton is illustrated as being delivered by H154. An important feature of Scheme 2 is the need to “reset” the active site at each step (A, BI-BIII, Scheme 1) via uptake of protons from solvent to H84 and H154 through an, as yet, unidentified pathway.

Previous studies from this laboratory have focused on O2 activation in a copper amine oxidase from H. polymorpha (HPAO) and in glucose oxidase (GO) from Aspergillus, leading to the identification of protein features that can facilitate O2 binding and reactivity in the absence of direct binding of O2 to a metal. In the HPAO instance, a hydrophobic pocket adjacent to an active site Cu2+ ion was proposed to be the site of initial O2 binding (26, 27), with electron transfer from the reduced active site cofactor (aminoquinol of TPQ) to bound O2 being facilitated by the +2 charge on the adjacent copper ion; subsequent binding of the superoxide anion onto copper and further reduction of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide completed the reaction cycle, returning the reduced quinol cofactor to its oxidized, quinone form. More recent studies, involving site-specific mutagenesis, xenon binding/X-ray crystallography (28) and molecular dynamics identified pathways for O2 to reach the proposed binding pocket in HPAO. While the off-metal binding in HPAO has been questioned in the case of the several plant copper amine oxidases (29, 30), all available data for HPAO support the described mechanism (9, 26).

In the case of GO, which contains a non-covalently bound flavin as cofactor, O2 has never been shown to saturate the enzyme, reacting instead via a second order process with reduced flavin. Despite the absence of evidence for a distinct O2-binding pocket, an active site histidine that sits near the N-1 position of the bound flavin has been shown to provide all of the catalysis required for reduction of O2 to superoxide ion. This is attributed to electrostatic catalysis of superoxide anion formation, with subsequent protonation and electron transfer leading to hydrogen peroxide (31, 32). In both HPAO and GO, the reduction of O2 is, thus, believed to occur via stepwise electron and proton transfers, as proposed in Scheme 2 for PqqC. Work by others on flavin-containing oxidases indicates pathways for O2 binding, as well as support for the importance of electrostatic catalysis (33–35).

The fact that PqqC contains neither a metal ion nor a redox cofactor places it into a unique family of proteins that also includes urate oxidase (UO) and coproporphryinogen oxidase (CPO) (36). In the case of urate oxidase, the use of high-pressure xenon binding and X-ray crystallography has identified an oxygen-binding pocket outside the active site (37). Recent studies have also found a polar site above the substrate in UO that can accommodate a water ion or chloride ion, with the latter being a reasonable mimic of an anionic superoxide intermediate. Inspection of the active site of UO indicates a structural motif that has some similarity to the O2 binding core of PqqC, with the presence of Lys (versus Arg in PqqC), Thr (versus Tyr in PqqC), as well as Asn that is seen in some PqqC variants. Mechanistically, PqqC, UO and CPO may differ. Both UO and CPO have been proposed to proceed via a hydroperoxy intermediate (36) though there is little experimental evidence to support this. There is no evidence to suggest that PqqC proceeds by a similar mechanism, leading to the proposal of outer-sphere electron transfer in Scheme 2. The most significant, unifying feature of PqqC, UO and CPO is the nature of the substrates themselves. In each instance, the reduced form of substrate has similarities to well-studied organic cofactors (e.g., reduced flavins and quinols) that are capable of one electron transfer to O2 to generate superoxide anion (38). Given that the first electron transfer to O2 to form O2−• is the most endothermic step in hydrogen peroxide formation (cf. 23), the major portion of catalysis in PqqC, UO and CPO is expected to depend on side chains that can catalyze the first electron transfer step from reduced substrate to O2 (24). The reactivity and redox capabilities, i.e. capacity for one electron chemistry, of their substrates sets these reactions apart.

As discussed earlier, among the three O2 core side chains in PqqC, two are completely conserved in all PqqC protein sequences; these are the Y175 and R179. Inspection of Figure 2 indicates that both the phenyl ring of Y175 and the long side chain of R179 could create a hydrophobic pocket for O2. Additionally, the tail of R179 is expected to contribute to electrostatic catalysis of superoxide anion production. Thus, these side chains have the potential to contribute both to O2 binding and to a subsequent rate-limiting outer sphere electron transfer from substrate to O2 to form a superoxide anion. In the case of position 154, which is also highly conserved, gene annotation indicates replacement by Asn in two sequences (RoseFigura and Klinman, in preparation). While this replacement could possibly have arisen from an error in sequencing3, we must also consider the possibility that a protonated histidine is not an absolute prerequisite for catalysis within the PqqC O2-binding/activation motif. If this is the case, the source of the second proton in hydrogen peroxide formation, Scheme 2, would have to reside at an as yet unidentified protein side chain. In this context, it may be important that among the mutants studied, only H154N is competent toward H2O2 reduction (Table 3).

The challenge for the future will be to tease apart the detailed properties of the O2 core that contribute to O2 binding versus catalysis. We consider it important that addition of O2 to mutant proteins promotes the appearance of new spectral species. This is the second example of a special role for non-metal O2 binding in promoting a conformational rearrangement during quino-cofactor biogenesis. In an earlier study of TPQ formation, it was shown that a charge transfer complex between the active site copper and the tyrosine (Y405) that is the precursor to TPQ occurs only after exposure of anaerobic protein samples to O2 (39, 40). It appears that for both TPQ and PQQ biogenesis, O2 binding can contribute to a restructuring of the active site that alters proton movement involving deprotonation (of Y405) in the case of TPQ biogenesis and most likely protonation of the quinoid intermediate in PQQ formation catalyzed by the PqqC mutants described herein.

Conclusion

The aggregate data presented in this study are consistent with an “O2 core” in PqqC. We have characterized four mutations that implicate the vital roles played by H154, Y175 and R179, with a change at any single position inhibiting PQQ production via a possible impact on a protein conformation change to the closed structure (Y175S), or a direct impairment of oxidative chemistry (H154N, Y175F, R179S). In the latter cases, it is further proposed that occupancy at the O2 binding pocket respositions H84, a residue previously shown (15) to be a requisite proton donor in quinol formation. Although the precise chemical nature of the species formed from the single turnover of “O2 core” mutants is not yet demonstrated, it is clear that these can persist for long times in the presence of O2. The present results, showing a binding of O2 to mutant forms of PqqC, add another example to the literature of gas-binding pockets that can be generated in the absence of either an organic cofactor or metal ion.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- PQQ

pyrroloquinoline quinone

- DCIP

dichloroindole phenol

- PMS

phenazine methosulfate

- NTA

nitriloacetic acid

- AHQQ

3a-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-4,5-dioxo-4,5,6,7,8,9-hexahydroquinoline-7,9-dicarboxylic acid

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- GDH

glucose dehydrogenase

Footnotes

Contribution from the Departments of Chemistry and Molecular and Cell Biology and the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (GM039296 to JPK) and the Austrian Science Fund (#P18702-B12 to RS).

H154S was not a good candidate for full kinetic characterization, given its demonstrated failure to form a closed enzyme/product complex.

The rate constants for PQQ formation were determined as 0.25 min−1 (WT2) versus 0.34 min−1 (WT1).

The glutamine codon (CAC/U) is only one base pair away from histidine (CAA/G).

Supporting Information Available: Single turnover reactions under anaerobic conditions for H154N and R179S. The anaerobic to aerobic transition for H154N. Single turnover reactions under aerobic conditions for H154N and R179S. Binding of PQQ to mutant enzymes. PQQH2 reoxidation to PQQ for H154N and Y175S. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Anthony C. Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) and quinoprotein enzymes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:757–774. doi: 10.1089/15230860152664966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakawa K, Sugino F, Kodama K, Ishii T, Kinashi H. Cyclization mechanism for the synthesis of macrocyclic antibiotic lankacidin in Streptomyces rochei. Chem Biol. 2005;12:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin PM, Anthony C. The biochemistry, physiology and genetics of PQQ and PQQ-containing enzymes. Advances in Microbial Physiology. 1998;40:1–80. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony C. The quinoprotein dehydrogenases for methanol and glucose. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;428:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storms DH, Rucker RB, Chen ILF, Jame M, Yang SJ. Pyrroloquinoline quinone: role in growth and development. FASEB J. 2003;17:Abstract No. 439.9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duine JA. The PQQ story. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;88:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(00)80002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He K, Nukada H, Urakami T, Murphy MP. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties of pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ): implications for its function in biological systems. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson AR, Jones LH, Higgins LA, Ashcroft AE, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL. Understanding quinone cofactor biogenesis in methylamine dehydrogenase through novel cofactor generation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3224–3230. doi: 10.1021/bi027073a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBois JL, Klinman JP. Mechanism of post-translational quinone formation in copper amine oxidases and its relationship to the catalytic turnover. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyama H, Chistoserdova L, Lidstrom ME. Sequence analysis of pqq genes required for biosynthesis of pyrroloquinoline quinone in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and the purification of a biosynthetic intermediate. Microbiology-Uk. 1997;143:595–602. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houck DR, Hanners JL, Unkefer CJ. Biosynthesis of pyrroloquinoline quinone. 2. Biosynthetic assembly from glutamate and tyrosine. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3162–3166. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnusson OT, Toyama H, Saeki M, Rojas A, Reed JC, Liddington RC, Klinman JP, Schwarzenbacher R. Quinone biogenesis: Structure and mechanism of PqqC, the final catalyst in the production of pyrroloquinoline quinone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7913–7918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402640101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnusson OT, Toyama H, Saeki M, Schwarzenbacher R, Klinman JP. The structure of a biosynthetic intermediate of pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) and elucidation of the final step of PQQ biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5342–5343. doi: 10.1021/ja0493852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puehringer S, RoseFigura JM, Metlitzky M, Toyama H, Klinman JP, Schwarzenbacher R. Structural studies of mutant forms of the PQQ-forming enzyme PqqC in the presence of product and substrate. Proteins-Struct Funct Bioinf. 2010;78:2554–2562. doi: 10.1002/prot.22769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnusson OT, RoseFigura JM, Toyama H, Schwarzenbacher R, Klinman JP. Pyrroloquinoline quinone biogenesis: Characterization of PqqC and its H84N and H84A active site variants. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7174–7186. doi: 10.1021/bi700162n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarzenbacher R, Stenner-Liewen F, Liewen H, Reed JC, Liddington RC. Crystal structure of PqqC from Klebsiella pneumoniae at 2.1 Å resolution. Proteins-Struct Funct Bioinf. 2004;56:401–403. doi: 10.1002/prot.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meulenberg JJM, Sellink E, Loenen WAM, Riegman NH, Vankleef M, Postma PW. Cloning of Klebsiella pneumoniae PQQ genes and PQQ biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Fems Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:337–344. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90244-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meulenberg JJM, Sellink E, Riegman NH, Postma PW. Nucleotide-sequencing and structure of the Klebsiella pneumoniae PQQ operon. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:284–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00280008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kriss GA. Astronomical Data Analysis Software & Systems III. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsthoorn AJJ, Duine JA. Production, characterization, and reconstitution of recombinant quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase (soluble type; EC 1.1.99.17) apoenzyme of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;336:42–48. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nabiullin AA, Fedoreev SA, Deshko TN. Circular dichroism of quinoid pigments from Far Eastern representatives of the family Boraginaceae. Chem Nat Compd. 1984;19:532–537. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toyama H, Fukumoto H, Saeki M, Matsushita K, Adachi O, Lidstrom ME. PqqC/D, which converts a biosynthetic intermediate to pyrroloquinoline quinone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:268–272. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wulfsberg G. Principles of Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry. University Science Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klinman JP. How do enzymes activate oxygen without inactivating themselves? Accts Chem Res. 2007;40:325–333. doi: 10.1021/ar6000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon EI, Chen P, Metz M, Lee SK, Palmer AE. Oxygen binding, activation, and reduction to water by copper proteins. Angew Chemie-Int Ed. 2001;40:4570–4590. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4570::aid-anie4570>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto Y, Klinman JP. Binding of dioxygen to non-metal sites in proteins: Exploration of the importance of binding site size versus hydrophobicity in the copper amine oxidase from. Hansenula polymorpha Biochemistry. 2002;41:13637–13643. doi: 10.1021/bi0204591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson BJ, Cohen J, Welford RW, Pearson AR, Schulten K, Klinman JP, Wilmot CM. Exploring molecular oxygen pathways in Hansenula polymorpha copper-containing amine oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17767–17776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701308200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pirrat P, Smith MA, Pearson AR, McPherson MJ, Phillips SEV. Structure of a xenon derivative of Escherichia coli copper amine oxidase: confirmation of the proposed oxygen entry pathway. Acta Crystallog Section F-Struct Biol Crystal Commun. 2008;64:1105–1109. doi: 10.1107/S1744309108036373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee A, Smirnov VV, Lanci MP, Brown DE, Shepard EM, Dooley DM, Roth JP. Inner-sphere mechanism for molecular oxygen reduction catalyzed by copper amine oxidases. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9459–9473. doi: 10.1021/ja801378f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepard EM, Okonski KM, Dooley DM. Kinetics and spectroscopic evidence that the Cu(I)-semiquinone intermediate reduces molecular oxygen in the oxidative half-reaction of Arthrobacter globiformis amine oxidase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13907–13920. doi: 10.1021/bi8011516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su Q, Klinman JP. Probing the mechanism of proton coupled electron transfer to dioxygen: The oxidative half reaction of bovinre serum amine oxidase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12513–12524. doi: 10.1021/bi981103l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roth JP, Klinman JP. Catalysis of electron transfer during activation of O2 by the flavoprotein glucose oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:62–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kommoju PR, Bruckner RC, Ferreira P, Carrell CJ, Mathews FS, Jorns MS. Factors that affect oxygen activation and coupling of the two redox cycles in the aromatization reaction catalyzed by NikD, an unusual amino acid oxidase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9542–9555. doi: 10.1021/bi901056a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finnegan S, Agniswamy J, Weber IT, Gadda G. Role of valine 464 in the flavin oxidation reaction catalyzed by choline oxidase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2952–2961. doi: 10.1021/bi902048c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pennati A, Gadda G. Involvement of ionizable groups in catalysis of human liver glycolate oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31214–31222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fetzner S, Steiner RA. Cofactor-independent oxidases and oxygenases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:791–804. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colloc’h N, Gabison L, Monard G, Altarsha M, Chiadmi M, Marassio G, Santos J, El Hajji M, Castro B, Abraini JH, Prange T. Oxygen pressurized X-ray crystallography: Probing the dioxygen binding site in cofactorless urate oxidase and implications for its catalytic mechanism. Biophys J. 2008;95:2415–2422. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.122184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Light DR, Walsh C, Ocallaghan AM, Goetzl EJ, Tauber AI. Characteristic of the cofactor requirements of the superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1468–1476. doi: 10.1021/bi00509a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams NK, Klinman JP. Whence topa? Models for the biogenesis of topa quinone in copper amine oxidases. J Mol Catal, B Enzym. 2000;8:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dove JE, Schwartz B, Williams NK, Klinman JP. Investigation of spectroscopic intermediates during copper-binding and TPQ formation in wild-type and active-site mutants of a copper-containing amine oxidase from yeast. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3690–3698. doi: 10.1021/bi992225w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.