Abstract

Aim:

To investigate the protective effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) against inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis in a rat model of resuscitated hemorrhagic shock.

Methods:

Hemorrhagic shock was induced in adult male SD rats by drawing blood from the femoral artery for 10 min. The mean arterial pressure was maintained at 35–40 mmHg for 1.5 h. After resuscitation the animals were observed for 200 min, and then killed. The lungs were harvested and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was prepared. The levels of relevant proteins were examined using Western blotting and immunohistochemical analyses. NaHS (28 μmol/kg, ip) was injected before the resuscitation.

Results:

Resuscitated hemorrhagic shock induced lung inflammatory responses and significantly increased the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α, and HMGB1 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Furthermore, resuscitated hemorrhagic shock caused marked oxidative stress in lung tissue as shown by significant increases in the production of reactive oxygen species H2O2 and ·OH, the translocation of Nrf2, an important regulator of antioxidant expression, into nucleus, and the decrease of thioredoxin 1 expression. Moreover, resuscitated hemorrhagic shock markedly increased the expression of death receptor Fas and Fas-ligand and the number apoptotic cells in lung tissue, as well as the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins FADD, active-caspase 3, active-caspase 8, Bax, and decreased the expression of Bcl-2. Injection with NaHS significantly attenuated these pathophysiological abnormalities induced by the resuscitated hemorrhagic shock.

Conclusion:

NaHS administration protects rat lungs against inflammatory responses induced by resuscitated hemorrhagic shock via suppressing oxidative stress and the Fas/FasL apoptotic signaling pathway.

Keywords: hemorrhagic shock, lung injury, inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, Fas/FasL, hydrogen sulfide, sodium hydrosulfide

Introduction

In recent years, H2S has been recognized, along with nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), as a third gaseous signaling molecule1. It is generally agreed that H2S exerts a variety of protective effects on multiple organs in pathophysiological processes. H2S has been reported to function as an anti-oxidant and is able to improve cardiac function, limit leukocyte adhesion and to enhance angiogenesis in a number of animal models2,3,4,5. Additionally, researchers have demonstrated that H2S administration may induce a “suspended animation-like state” in small mammals such as mice and rats6,7 but not in larger mammals such as pigs8. There have recently been a number of large studies that were designed to investigate the beneficial effects of H2S on important organs. Jiang and colleagues demonstrated that, in rats, exogenous H2S alleviates heroin-induced hippocampal damage through its antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects9. Another group of researchers has shown the protective effects of H2S on the hepatotoxicity induced by acetaminophen in mice10. A study by Lee et al proposed that hydrogen sulfide inhibits the increased glucose-induced matrix protein synthesis in renal epithelial cells11. Similarly, hydrogen sulfide has also been shown to attenuate hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cardiomyocytic endoplasmic reticulum stress in rats12. A recent study in pigs has shown that intravenous sulfide administration protects multiple organs against hemorrhagic shock (HS)13. Studies have also suggested that hydrogen sulfide protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury14. Finally, a new study has recently shown that hydrogen sulfide decreases the generation of reactive oxygen species in a rabbit model of lung transplantation15.

Hemorrhagic shock has been recognized as a predictor of poor outcome and as a leading cause of death in injured patients worldwide. The pathophysiologic process of HS is complex, and involves, among other events, hypovolemia, hypoxemia, microcirculatory disturbances, oxidative stress, the release of significant amounts of toxic chemical mediators, and apoptosis16. These alterations during HS are the primary cause of the subsequent development of multiple organs failure (MOF), a systemic inflammatory process that leads to the dysfunction of vital organs and that results in a high mortality rate17. Important organs, such as the lungs, are susceptible to such changes. The mechanisms that lead to organ injury induced by HS have not been fully elucidated; however, apoptosis is considered to be an underlying factor in acute lung injury18. It is well-established that lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury is associated with apoptosis involving Fas/FasL interactions19. Although different from the cell death patterns observed during LPS-induced lung injury, hyperoxia and ischemia-reperfusion injury are the main causes of complex cell death that include apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis20,21. Dimtrios and colleagues have suggested that two programmed cell death pathways exist in the lungs in rat models of trauma-hemorrhagic shock22. These two pathways involve endothelial cell death via a caspase-independent way and epithelial cell apoptosis through a caspase-dependent pathway.

Given the various protective effects of H2S mentioned above, we explored the anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-apoptotic effects of H2S in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock induced acute lung injury.

Materials and methods

Materials

NaHS and pentobarbital sodium were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich CO LLC, MO, USA). Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interlukin-6 (IL-6) ELISA kits were obtained from R&D (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The primary antibodies against high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) were purchased from Epitomics (Epitomics, CA, USA). The primary antibody against nuclear erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) was from Bioworld Technology (Nanjing, China). The anti-rat monocytes/macrophages antibody (ED1) was purchased from the Millipore Corporation. The commercial kits for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (·OH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) were obtained from the Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). The primary antibodies against Fas, FasL, active-caspase 8, active-caspase 3, FADD, BID, Bcl-2, and Bax were all purchased from Abcam (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The commercial immunohistochemistry staining kit was from ZSGB-BIO CO Ltd (Beijing, China). A commercial in situ cell death detection kit was from Roche Ltd (Basel, Switzerland). An ECL kit for signal detecting was purchased from BestBio Inc (Shanghai, China).

Animals

We used age-matched adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats that weighed 250–350 g with an average weight of approximate 280 g in this study. All the animals were from the Animal Center of the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi-an, China) and received humane care in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Publication No 85–23, revised 1996). The protocol number from the Human and Animal Ethics Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University is DSJYDXLL-2012510. All animals were fed a standard rodent diet (purchased from the Animal Center of the Fourth Military Medical University).

Animal groups and the hemorrhagic shock model

A total of 32 rats were used in the present study. The animals were randomly assigned to 4 groups (8 rats for each group) as follows: (1) Sham-operated animals (Sham group); (2) Sham-operated animals that were treated with sodium sulfide (NaHS) (Sham+NaHS group); (3) hemorrhagic shock animals (HS group); and (4) hemorrhagic shock animals that were treated with NaHS (HS+NaHS group). After 1 week of acclimatization, the rats were fasted overnight prior to the experiments but were allowed free access to water. The rat hemorrhagic shock model was performed as has previously been described23. The optimal dose of NaHS (28 μmol/kg) to be administered to the animals was determined by our preliminary experiments (See the Supplemental data). In brief, blood was drawn from the femoral artery of the rats over a 10-min period to induce a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 35–40 mmHg and to maintain a condition of shock for 1.5 h. One bolus dose of NaHS (28 μmol/kg, ip) was administered to the rats before resuscitation. The rats were observed for 200 min after the resuscitation. The rats in the HS group underwent all of the surgical procedures and were given 0.9% NaCl in place of an equal volume of the NaHS solution before resuscitation. The rats in the Sham group also underwent all of the surgical procedures but neither hemorrhage nor resuscitation was performed. The rats in the Sham+NaHS group underwent the same procedure as did the Sham group, except that the NaHS was administered at the time of resuscitation. All of the experimental animals were sacrificed by injection with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium after the procedures were completed. The lungs were harvested immediately, and the left lower lobes were sectioned into 3-mm-thick slices that were immersed in 10% formalin for subsequent analysis. Part of the left lung was cut and weighed to obtain the wet lung weight. Bronchoalveolar lavage of the right lung was then performed. The remaining lung tissue was stored in a −70 °C freezer for subsequent analyses.

Lung wet to dry ratio and morphological investigation

The lung wet to dry weight ratios were calculated to assess the magnitude of pulmonary edema induced by the hemorrhagic shock. After the wet lungs were weighed, they were desiccated in an oven at 80 °C for 72 h to obtain a stable dry weight. The ratio of the wet/dry weight was then calculated. To investigate the morphological changes in the lungs induced by hemorrhagic shock, hematoxylin and eosin staining (HE) was performed according to a standard protocol. To evaluate the degree of the morphological changes in the lung tissue, the HE stained slides were analyzed by a pathologist who was blinded to the identity of the experimental groups.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid preparation and analysis of inflammatory cytokines

At the end of the experiment, bronchoalveolar lavage of the right lung was performed on all of the experimental groups (n=8, respectively) by washing the lung five times with 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline. Approximately 90% (4.5 mL) of the starting lavage fluid volume was consistently retrieved. The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was centrifuged at 450×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was then stored at −70 °C for later analysis. The concentration of protein in the lavage fluid was measured using Bradford's method with bovine serum albumin used as a standard24. The concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were determined using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, after the lavage samples were collected, the samples and reagents were added to the assay wells in order and the optical densities were read by a spectrophotometer (PowerWave XS, BioTek Inc, VT, USA) at 450 nm (with a correction wavelength at 540 nm). Then, the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 were calculated accordingly.

Myeloperoxidase assays

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured using a commercially available kit (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) to assess the neutrophilic infiltration into the lung. In short, lung samples from each group were homogenized in ice cold saline (with a 1:10 ratio of lung tissue to saline). The homogenates were then processed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, myeloperoxidase was detected using a spectrophotometer at 460 nm (PowerWave XS, BioTek Inc, VT, USA), and the MPO activity was thereby obtained.

Oxidative stress analysis

H2O2 and ·OH were used as a surrogate for the production of reactive oxygen species during HS induced oxidative stress in vivo. The lung tissue was homogenized in 0.01 mol/L phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). After centrifugation at 1200×g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and the reagents were added according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance was detected using a spectrophotometer at 560 nm, and the concentrations of H2O2 and ·OH were then calculated.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining

A commercial in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) was used in this study according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the tissue sections were dewaxed according to standard protocols and then were microwave heat treated. The slides were immersed in Tris-HCl (0.1 mol/L, pH 7.5) containing 3% BSA and 20% normal bovine serum for 30 min. To exclude the staining of apoptotic inflammatory cells that are present in the lungs after HS, the slides were incubated with an antibody against ED1 (1:200, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) overnight before proceeding with the staining. The corresponding secondary antibody was incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. After being washed twice in PBS, the slides were covered with the TUNEL reaction mixture. The slides were then incubated for 60 min at 37 °C in a humidified chamber in the dark. Then, the slides were washed three times with PBS for 5 min each. The apoptotic cells were counted by a pathologist under a fluorescence microscope. The apoptotic cells in 10 consecutive visual fields were counted in each histological section using a ×40 objective.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays

After being dewaxed, the paraffin sections (4 μm thick) were incubated at 4 °C overnight in the presence of primary antibodies raised against HMGB1 (1:200, Epitomics, CA, USA), Fas (1:150, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and Fas ligand (1:150, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Then, the sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies at 37 °C for 1 h. The final antibody complex was visualized using a commercial immunohistochemistry staining kit (ZSGB-BIO CO Ltd, Beijing, China). The stained sections were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0, Media Cybernetics, Inc, MD, USA) by a pathologist who was blinded to the identity of the groups. The integrated optical density (IOD) was calculated by measuring 10 consecutive visual fields for each sample using a 40×objective. All data were gathered and used to calculate a mean value. A statistical analysis was used to compare the results obtained from different experimental groups.

Western blotting assays

The lung tissue samples were homogenized in 1 mL of ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Inc, Haimen, China). The homogenates were then centrifuged at 800×g to remove the cellular debris. After the pellet had been discarded, the supernatant was again centrifuged at 12 000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was collected. The resulting pellet was resuspended in mitochondrial lysis buffer to obtain the mitochondrial fraction. The nuclear protein was extracted using a commercial kit (BestBio Inc, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equivalent amounts of protein (30 μg) from each sample were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and were then transferred onto 0.22 μmol/L nitrocellulose filter membranes (Millipore, Bedford, USA). The primary antibodies were incubated at 4 °C overnight. The dilutions of primary antibodies that were used were anti-Nrf2 (1:200), anti-Trx1 (1:1000), anti-active-caspase 8 (1:1000), anti-active-caspase 3 (1:2000), anti-FADD (1:500), anti-BID (1:2000), anti-Bcl-2 (1:100), and anti-Bax (1:1500). The secondary antibodies were incubated, and the signals were detected using an ECL kit (BestBio Inc, Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the mean±SD. Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Fisher's LSD post hoc multiple comparisons test (SPSS for Windows version 16.0, Chicago, USA). A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

NaHS alleviates lung injury in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock

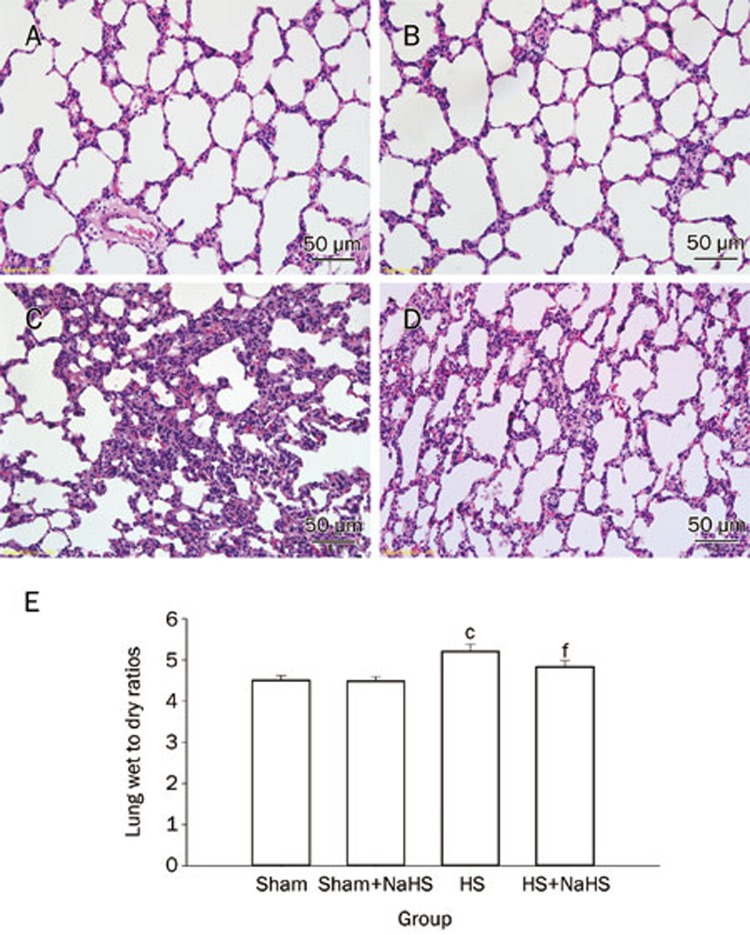

The pulmonary histology observed microscopically showed that the lung structure was normal with well-defined pulmonary alveoli in the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 1A and 1B). Furthermore, hemorrhagic shock caused acute alveolar injury and inflammation (Figure 1C); the histopathologic changes in the lung were characterized by the aggregation of red blood cells, edema, the infiltration of inflammatory cells, markedly thickened alveolar walls, and the destruction of alveoli. The NaHS treatment notably attenuated these features of lung injury (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

NaHS alleviates lung injury after hemorrhagic shock-resuscitation in rats. (A–D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of rat lungs (original magnification ×20). Scale bars=50 μm; (E) Rat lung wet to dry ratios. cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. fP<0.01 vs the HS group. The data are expressed as the mean±SD. n=8. (A) Sham group; (B) Sham+NaHS group; (C) HS group; (D) HS+NaHS group.

The wet to dry ratios of the lungs were calculated to assess the edema induced by hemorrhagic shock. HS increased the wet to dry ratio (Figure 1E; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups) while NaHS treatment considerably decreased the wet to dry ratio (Figure 1E; P<0.01 vs the HS group).

NaHS decreases rat lung protein leakage, the inflammatory response, and neutrophilic infiltration that is induced by hemorrhagic shock

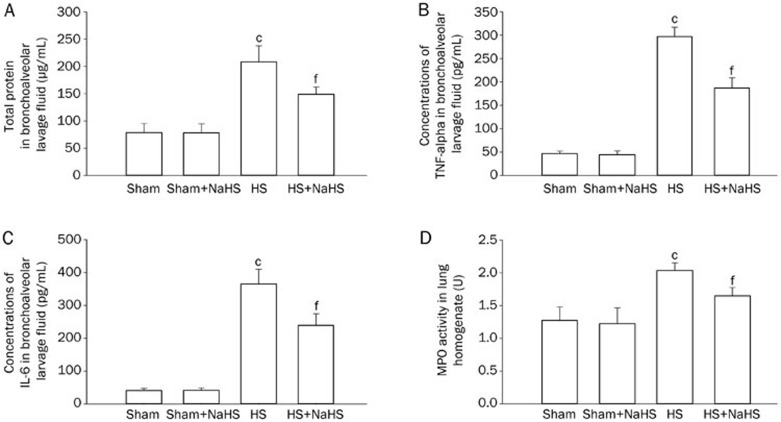

The degree of hemorrhagic shock-induced lung leakage in the rat lungs was measured by the amount of protein that was present in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, which indicated the severity of the lung injury. We could clearly see a considerable increase in the amount of protein in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after hemorrhagic shock, which indicates that hemorrhagic shock increases the permeability of the lung and the leakage of protein from the blood vessels (Figure 2A; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups). However, the protein leakage was attenuated by the administration of NaHS (Figure 2A; P<0.01 vs the HS group). We then analyzed the effects of NaHS on the inflammatory response to hemorrhagic shock, and the ELISA data showed an increase in the concentration of TNF-α after HS (Figure 2B; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups), which was effectively attenuated by the NaHS treatment (Figure 2B; P<0.01 vs the HS group). Similarly, the concentration of IL-6 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid increased after HS (Figure 2C; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups). The increase in IL-6 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was effectively attenuated by NaHS treatment (Figure 2C; P<0.01 vs the HS group). There was no difference between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups in the concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α (Figure 2B and 2C).

Figure 2.

NaHS decreases rat lung protein leakage, the inflammatory response, and the neutrophilic infiltration induced by hemorrhagic shock. (A) Total bronchoalveolar lavage fluid assay; (B) Concentrations of TNF-α in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; (C) Concentrations of IL-6 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; (D) MPO assay. The values are expressed as the mean±SD. n=8. cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. fP<0.01 vs the HS group.

A myeloperoxidase activity assay was performed to assess the degree of neutrophilic infiltration in the rat lungs after hemorrhagic shock. The myeloperoxidase activity in the lung tissue increased considerably after hemorrhagic shock in comparison with the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 2D; P<0.01), whereas this activity was significantly reduced in the NaHS treated group (Figure 2D; P<0.01 vs the HS group). There was no difference in the myeloperoxidase activity observed between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 2D).

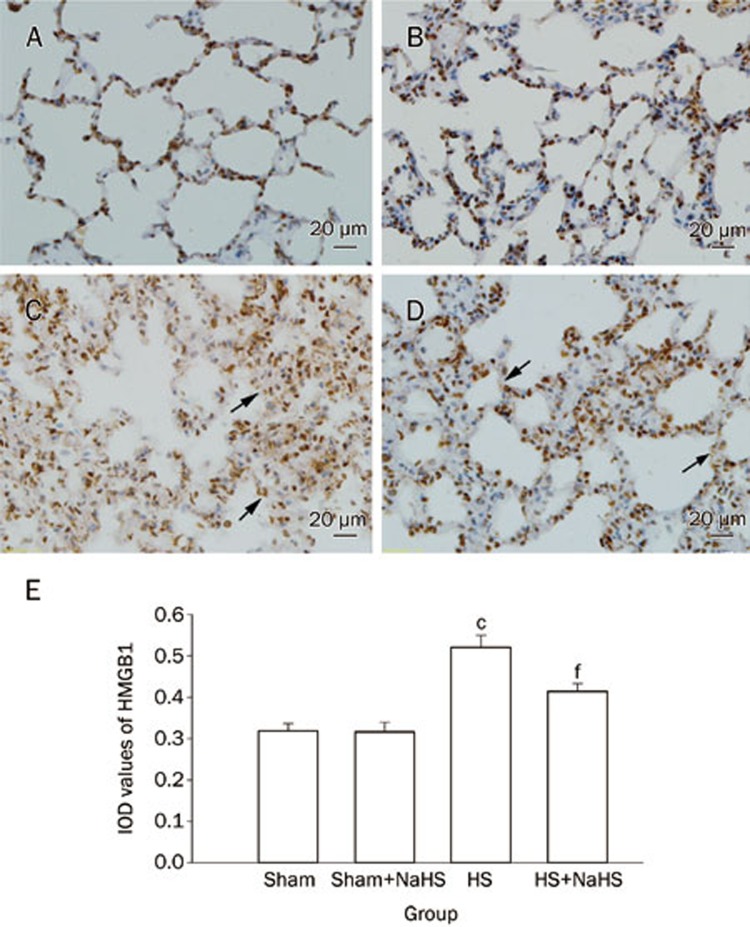

Additionally, the expression of the late phase inflammatory factor HMGB1 was measured by IHC. HMGB1 expression dramatically increased after hemorrhagic shock (Figure 3C and 3E; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS group). The NaHS treatment effectively reduced HMGB1 expression after HS (Figure 3D and 3E; P<0.01 vs the HS group). However, there was no difference in the expression of HMGB1 between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

NaHS decreases the expression of HMGB1 in rat lungs. Representative IHC staining of HMGB1 (original magnification ×40). Scale bars=20 μm. The brown staining represents positive HMGB1 staining. The black arrows indicate the HMGB1 protein being transferred from the nuclear to the intracellular spaces after HS. cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. fP<0.01 vs the HS group. (A) Sham group; (B) Sham+NaHS group; (C) HS group; (D) HS+NaHS group.

NaHS decreases the oxidative stress that is induced by hemorrhagic shock

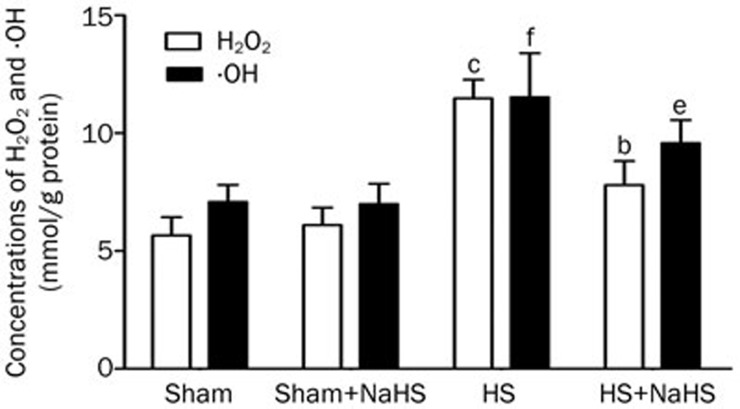

Hemorrhagic shock increased the production of the reactive oxygen species H2O2 and ·OH (Figure 4, P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups). However, NaHS treatment notably decreased the amount of these two reactive oxygen species (Figure 4, P<0.01 vs the HS group).

Figure 4.

NaHS decreases oxidative stress induced by hemorrhagic shock. H2O2 and ·OH assays. bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 vs the HS group.

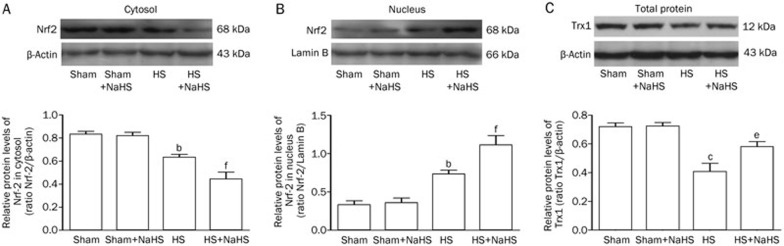

NaHS up-regulates the translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus and the expression of Trx1 after hemorrhagic shock

Hemorrhagic shock increased the translocation of nuclear factor erythroid-2 (Nrf2) into the nucleus (Figure 5A and 5B, P<0.05 and P<0.05 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups). NaHS significantly increased Nrf2 translocation into the nucleus (Figure 5A and 5B, P<0.05 and P<0.01 vs the HS group). Trx1 expression notably decreased after hemorrhagic shock (Figure 5C, P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups), and NaHS administration reversed this (Figure 5C, P<0.05 vs the HS group).

Figure 5.

NaHS enhances the translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus and increases the expression of Trx1. (A) Western blotting assays for Nrf2 expression in the cytosol in rat lungs, (B) Nrf2 expression in the nucleus in rat lungs, and (C) Trx1 expression in the total protein in rat lungs separately. bP<0.05, cP<0.05 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 vs the HS group.

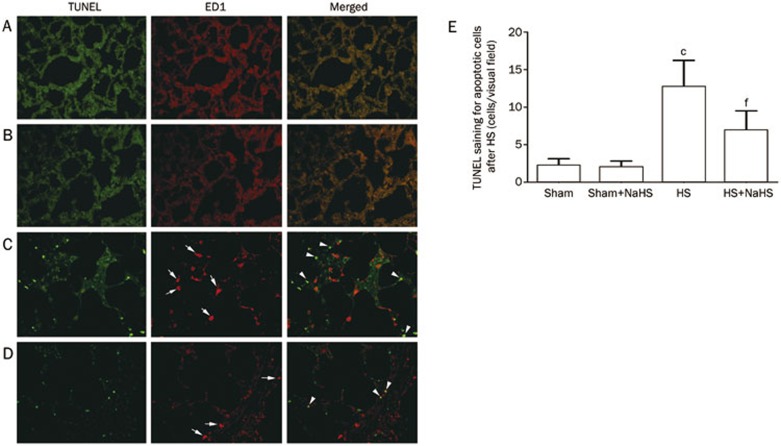

NaHS attenuates apoptosis induced by hemorrhagic shock

The data showed an obvious increase in the number of apoptotic cells in the rat lungs after HS (Figure 6C and 6E; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups). In contrast, NaHS administration evidently alleviated the apoptotic response (Figure 6D and 6E; P<0.01 compared with HS group), and few apoptotic cells were detected in the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 6A and 6B).

Figure 6.

NaHS attenuates the apoptosis induced by hemorrhagic shock in rat lungs. TUNEL staining of rat lungs; the red stained cells indicated by the white arrows are monocytes or macrophages, and the green stained cells indicated by the white arrowheads are the apoptotic cells induced by HS. cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. fP<0.01 vs the HS group. (A) Sham group; (B) Sham+NaHS group; (C) HS group; (D) HS+NaHS group.

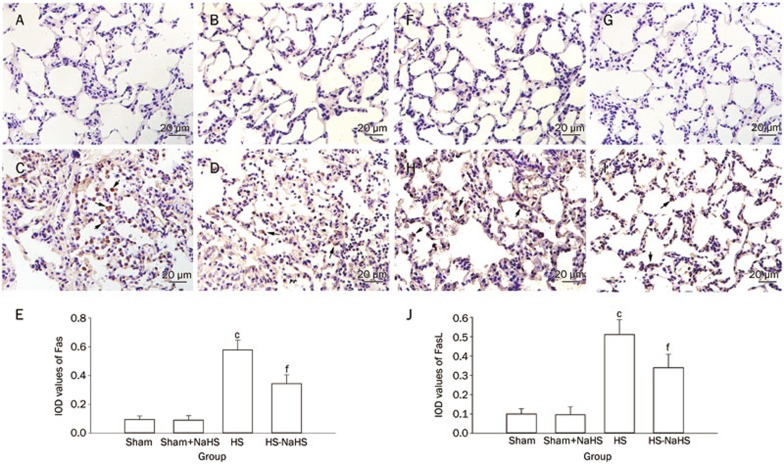

NaHS inhibits the expression of Fas and FasL during hemorrhagic shock

Hemorrhagic shock elevated the death receptor Fas (Figure 7C and 7E; P<0.01 compared with the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups). Administration of NaHS reduced the expression of Fas (Figure 7D and 7E; P<0.01 vs the HS group). However, there was no difference between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 7A–7E). Similarly, the expression of Fas-ligand also increased following HS (Figure 7H and 7J; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups), and the NaHS treatment reduced its expression when it was compared with that observed in the HS group (Figure 7I and 7J; P<0.01). Similarly, there was no difference between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 7F, 7G, and 7J).

Figure 7.

NaHS inhibits the expression of Fas/FasL induced by hemorrhagic shock in rat lungs. (A–E) IHC staining of Fas in rat lungs, the black arrows indicate cells stained positively for Fas; (F–J) IHC staining of FasL in rat lungs, the black arrows indicate cells stained positively for FasL. Original magnification ×40. Scale bars=20 μm. cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. fP<0.01 vs the HS group. (A, F) Sham group; (B, G) Sham+NaHS group; (C, H) HS group; (D, I) HS+NaHS group.

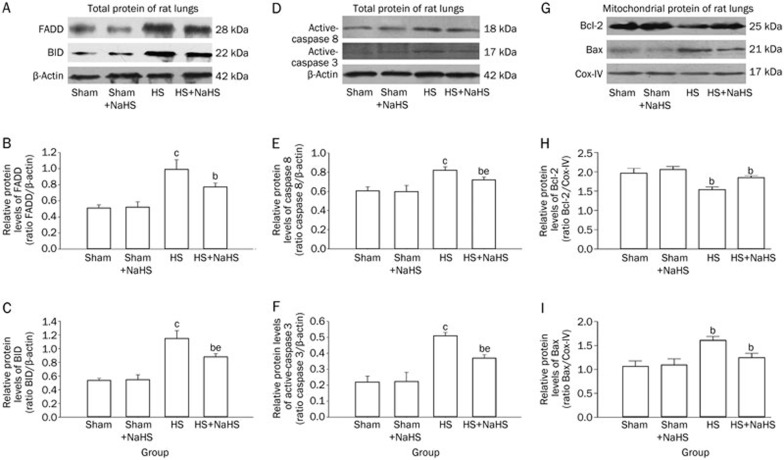

NaHS attenuates the increase in expression of apoptosis-related proteins that are induced by hemorrhagic shock

Hemorrhagic shock increased the expression of Fas-associated death domain (FADD) when compared with both the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 8A and 8B; P<0.01), and administration of NaHS reduced the expression of FADD (Figure 8A and 8B; P<0.05 vs the HS group). There was no difference in FADD expression between the Sham and Sham+NaHS group (Figure 8A, 8B). An increase in BID expression was observed in the HS group (Figure 8A and 8C; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups), and NaHS treatment notably inhibited the increase in BID expression when it was compared with that observed in the HS group (Figure 8A and 8C; P<0.05).

Figure 8.

NaHS inhibits the expression of hemorrhagic shock induced apoptosis-related proteins in rat lungs. Western blotting assays for hemorrhagic shock induced apoptosis-related protein expression. (A) Representative Western blotting for the expression of FADD and BID. (D) Representative Western blotting for the expression of active-caspase 8 and caspase 3. (G) Representative Western blotting for the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax. bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 vs the HS group.

Our data showed that hemorrhagic shock induced a notable increase in the expression of active-caspase 8 (Figure 8D and 8E; P<0.01, P<0.05 vs the Sham group), and NaHS treatment decreased the expression of active-caspase 8 (Figure 8D and 8E; P<0.05 vs the HS group). There was no difference in active-caspase 8 expression between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 8D and 8E). Similarly, hemorrhagic shock increased the expression of active-caspase 3 (Figure 8D and 8F; P<0.01, P<0.05 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups), while the NaHS treatment decreased active-caspase 3 expression (Figure 8D and 8F; P<0.05 vs the HS group). There was no difference in active-caspase 3 expression between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 8D and 8F).

Finally, hemorrhagic shock also resulted in lower Bcl-2 expression when compared with both the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 8G and 8H; P<0.01). The NaHS treatment reversed the drop in Bcl-2 expression (Figure 8G and 8H; P<0.05 vs the HS group). However, increased Bax expression was found after HS (Figure 8G and 8I; P<0.01 vs the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups), and NaHS treatment reduced Bax expression (Figure 8G and 8I; P<0.05 compared with the HS group). Again, there was no difference between the Sham and Sham+NaHS groups (Figure 8G and 8I).

Discussion

H2S is recognized as a promising drug candidate and is now the subject of intense research. IK1001, an injectable H2S donor, was recently demonstrated to attenuate hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury because of its anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic properties25. GYY4137, a new slowly releasing hydrogen sulfide donor also was recently shown to protect against endotoxic shock in the rat at a dose of 50 mg/kg ip26. NaHS, an exogenous donor of H2S, has also been shown to be protective in a variety of animal models of disease15. Our previously published study demonstrated that NaHS administration ameliorated hemodynamic deterioration, the inflammatory response, and the myocardial tissue injury that are caused by hemorrhagic shock23. The present study supports our previous findings by examining the role of sodium hydrosulfide on hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury in rats.

Although most of the published studies have reported that H2S is able to reduce a variety of organs damage in animal models of disease, Drabek et al have argued that intravenous administration of hydrogen sulfide does not induce hypothermia or improve survival from hemorrhagic shock in pigs8; this result was not in accordance with the results reported by Blackstone6.

Similarly, whether H2S has anti- or pro-inflammatory effects remains controversial. It is generally agreed that H2S inhibits the inflammatory response in a number of animal models of disease7,27; however, Collin et al recently reported that H2S acts as an inflammatory mediator in lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in both mice and rats28,29. Additionally, a study by Mok et al proposed that H2S may participate in the inflammatory response to HS by inhibiting H2S biosynthesis30. However, Zanardo et al demonstrated that H2S modulates leukocyte adherence to the vascular endothelium by activating KATP channels31. According to a new report, Seitz and colleagues showed that continuously inhaled hydrogen sulfide induces suspended animation but that it did not alter the inflammatory response to blunt chest trauma32. Our study shows that, although administration of a single dose of 28 μmol/kg NaHS significantly attenuated inflammation and decreased oxidative stress and apoptosis that was induced by HS, it did not induce the “suspended animation like effect” in our rat model of HS because there were no significant changes in the body temperatures observed in the experimental animals (data not shown). A single dose of NaHS, which is different from the continuously inhaled hydrogen sulfide treatment described above, may be insufficient to induce the “suspended animation like effect”. Thus, in the present study, the protective effects of NaHS observed during HS-resuscitation may not be due to the “suspended animation like effect”. The present study showed that HS induced significant expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and HMGB1. However, the administration of 28 μmol/kg NaHS significantly inhibited the inflammation induced by HS in rats. The key inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and HMGB1 decreased dramatically after the NaHS treatment, and this was accompanied by a notable attenuation of the injury that is typically induced by HS. These results were consistent with our previously published observations33. The aforementioned discrepancies between the anti-inflammatory and the pro-inflammatory effects of H2S may be due in part to the use of different animal models, different drugs and different concentrations, and may also be due in part to the administration of those drugs through different routes. Understanding these discrepancies may provide useful points of reference in the search to develop new drugs that target pathways that are modulated by H2S under varying conditions.

We further studied the anti-oxidative stress effects of NaHS on rat lungs after HS. Our results show that NaHS decreases the reactive oxygen species H2O2 and ·OH that are induced during HS. Nrf2 is an important regulator of antioxidant expression, and we also observed that NaHS improves translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus, which is accompanied by increased expression of Trx1. The present study was partly consistent with a very recent report, in which Li and colleagues showed that NaHS attenuated hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury that was associated with reduced oxidative stress, decreased inflammation, and reduced lung permeability in mice34.

The inflammatory response and apoptosis are two key features of the promotion and progression of HS. The oxygen free radicals, metabolites, and cytokines that are induced by ischemia and reperfusion after resuscitation from HS participate in the organ injury, the inflammatory response and the cellular apoptosis that follow35,36. Fas is an important pro-apoptotic factor and a member of the TNF-receptor superfamily that is expressed in a variety of cell types and tissues37. When it interacts with its natural ligand, FasL, Fas activates the apoptotic cascade through the caspases, thereby participating in a number of pathophysiological processes38. There is significant crosstalk between the apoptotic pathway and the inflammatory pathways, and the relationship between Fas/FasL and inflammation is being studied extensively. Increasing evidence now shows that the Fas/FasL system mediates inflammation, lung injury, and apoptosis in many diseases39,40. Studies aimed at investigating the roles of Fas/FasL during disease have been undertaken. Niu and colleagues reported that neutralization of FasL attenuates brain inflammation in a model of experimental stroke in mice41.

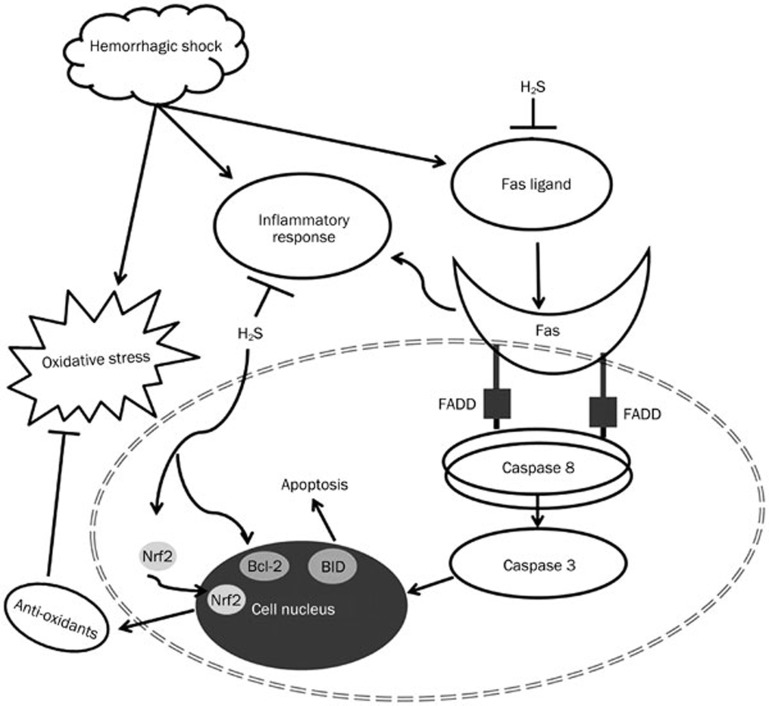

The anti-apoptotic effects of H2S have been widely reported by researchers both in vivo and in vitro42,43,44. However, few studies have investigated the effects of H2S on HS, and even fewer have addressed the underlying mechanisms. Our study has shown that Fas and FasL expression, together with a number of other pro-apoptotic proteins, were significantly increased in rat lungs after HS and resuscitation. Administration of NaHS notably inhibited the increased expression of pro-apoptotic proteins involved in the Fas/FasL signaling pathway. As we showed in the in situ cell death assays, the apoptotic cells were primarily located in the alveolar epithelia and alveolar interstitial cells, and administration of NaHS noticeably decreased the number of apoptotic cells present in those anatomic compartments. The Bcl-2 family plays an important role in the Fas/FasL apoptotic signaling pathway. There are two members of the Bcl-2 family that serve opposing functions; Bcl-2 maintains cell survival and its closest homolog promotes apoptosis45. After an apoptotic signal is transmitted by FADD, caspases are activated to facilitate the progression of cellular apoptosis46. Our data show that the expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins BID and Bax was reduced following NaHS treatment, whereas the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 increased. The increased expression of Bcl-2 protected against apoptosis caused by resuscitated HS as shown by the decreased expression of active-caspase 8, caspase 3 and FADD in the NaHS treated rats. The present study further examined the anti-apoptotic roles of H2S in resuscitated HS and was partially consistent with a previous study published by John et al47. Our results add to previous observations25 that suggest that the anti-apoptotic effects of hydrogen sulfide protect from hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury through anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic signaling. Our data show that NaHS increases the expression of the Bcl-2 protein; however, the possibility exists that H2S preserves mitochondrial function by inhibiting mitochondria-dependent cell apoptosis during HS. However, this question has not yet been addressed experimentally. In summary, NaHS confers protection against lung injury in rats and inhibits lung apoptosis after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation by attenuating the inflammatory response, decreasing oxidative stress, and inhibiting the Fas/FasL signaling pathway. These results suggest that H2S is a promising therapeutic drug for the treatment of lung injury caused by resuscitated HS. The possible mechanisms of the anti-apoptotic effects of NaHS are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Illustration of the H2S inhibition of hemorrhagic shock induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptotic signaling. Exogenous H2S may attenuate the HS induced lung injury by decreasing the inflammation, oxidative stress, and Fas/FasL signaling.

Author contribution

Dun-quan XU and Cao GAO designed the experiments, performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript; Dun-quan XU, Wen NIU, and Yan-xia WANG performed the animal experiments; Yan-xia WANG, Qian DING, and Li-nong YAO performed the IHC and TUNEL assays; Dun-quan XU, Cao GAO, and Wen NIU performed the Western blotting assays; Chang-jun GAO and Li-nong YAO performed additional data analysis; Yan LI offered careful editing work on the manuscript; Zhi-chao LI and Wei CHAI conceived the entire study and critically reviewed the manuscript. All of the co-authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 30872444, 81200036, and 81272133). We thank Miss Qing-yi WANG for her English language expertise.

References

- Wang R. Two's company, three's a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter. FASEB J. 2002;16:1792–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0211hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide protects neurons from oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2004;18:1165–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1815fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YZ, Wang ZJ, Ho P, Loke YY, Zhu YC, Huang SH, et al. Hydrogen sulfide and its possible roles in myocardial ischemia in experimental rats. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:261–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00096.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MJ, Cai WJ, Li N, Ding YJ, Chen Y, Zhu YC. The hydrogen sulfide donor NaHS promotes angiogenesis in a rat model of hind limb ischemia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1065–77. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi S, Kang L, Kimura T, Niki I. Hydrogen sulphide protects mouse pancreatic beta-cells from cell death induced by oxidative stress, but not by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1171–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science. 2005;308:518. doi: 10.1126/science.1108581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslami H, Heinen A, Roelofs JJ, Zuurbier CJ, Schultz MJ, Juffermans NP. Suspended animation inducer hydrogen sulfide is protective in an in vivo model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1946–52. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2022-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabek T, Kochanek PM, Stezoski J, Wu X, Bayir H, Morhard RC, et al. Intravenous hydrogen sulfide does not induce hypothermia or improve survival from hemorrhagic shock in pigs. Shock. 2011;35:67–73. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e86f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang LH, Luo X, He W, Huang XX, Cheng TT. Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulfide on apoptosis proteins and oxidative stress in the hippocampus of rats undergoing heroin withdrawal. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:2155–62. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-1220-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsy MA, Ibrahim SA, Abdelwahab SA, Zedan MZ, Elbitar HI. Curative effects of hydrogen sulfide against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Life Sci. 2010;87:692–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Mariappan MM, Feliers D, Cavaglieri RC, Sataranatarajan K, Abboud HE, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits high glucose-induced matrix protein synthesis by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4451–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Zhang R, Jin H, Liu D, Tang X, Tang C, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cardiomyocytic endoplasmic reticulum stress in rats. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1079–91. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracht H, Scheuerle A, Groger M, Hauser B, Matallo J, McCook O, et al. Effects of intravenous sulfide during resuscitated porcine hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2157–67. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e6b30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller S, Zimmermann KK, Strosing KM, Engelstaedter H, Buerkle H, Schmidt R, et al. Inhaled hydrogen sulfide protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Med Gas Res. 2012;2:26. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TJ, Arnaoutakis GJ, Beaty CA, Jandu SK, Santhanam L, Berkowitz DE, et al. Hydrogen sulfide decreases reactive oxygen in a model of lung transplantation. J Surg Res. 2012;178:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angele MK, Schneider CP, Chaudry IH. Bench-to-bedside review: latest results in hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care. 2008;12:218. doi: 10.1186/cc6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai B, Deitch EA, Ulloa L. Novel insights for systemic inflammation in sepsis and hemorrhage. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:642462. doi: 10.1155/2010/642462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang PS, Mura M, Seth R, Liu M. Acute lung injury and cell death: how many ways can cells die. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L632–41. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00262.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Winn RK, Martin TR, Liles WC. Sustained lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation in mice is attenuated by functional deficiency of the Fas/Fas ligand system. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:358–61. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.358-361.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Chao Y, Powell JL, Rubin LP, Sharma S. Hyperoxia-induced apoptosis and Fas/FasL expression in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L647–59. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00445.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Perrot M, Liu M, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S. Ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:490–511. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-670SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlos D, Deitch EA, Watkins AC, Caputo FJ, Lu Q, Abungu B, et al. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock-induced pulmonary epithelial and endothelial cell injury utilizes different programmed cell death signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L404–17. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00491.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C, Xu DQ, Gao CJ, Ding Q, Yao LN, Li ZC, et al. An exogenous hydrogen sulphide donor, NaHS, inhibits the nuclear factor kappaB inhibitor kinase/nuclear factor kappab inhibitor/nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway and exerts cardioprotective effects in a rat hemorrhagic shock model. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:1029–34. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b110679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha S, Calvert JW, Duranski MR, Ramachandran A, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of antioxidant and antiapoptotic signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H801–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Salto-Tellez M, Tan CH, Whiteman M, Moore PK. GYY4137, a novel hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule, protects against endotoxic shock in the rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Dong Z, Dimitropoulou C, Su Y. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates tobacco smoke-induced oxidative stress and emphysema in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:2121–34. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bhatia M, Zhu YZ, Zhu YC, Ramnath RD, Wang ZJ, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is a novel mediator of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in the mouse. FASEB J. 2005;19:1196–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3583fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin M, Anuar FB, Murch O, Bhatia M, Moore PK, Thiemermann C. Inhibition of endogenous hydrogen sulfide formation reduces the organ injury caused by endotoxemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:498–505. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok YY, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulphide is pro-inflammatory in haemorrhagic shock. Inflamm Res. 2008;57:512–8. doi: 10.1007/s00011-008-7231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanardo RC, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Cirino G, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. FASEB J. 2006;20:2118–20. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6270fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz DH, Froba JS, Niesler U, Palmer A, Veltkamp HA, Braumuller ST, et al. Inhaled hydrogen sulfide induces suspended animation, but does not alter the inflammatory response after blunt chest trauma. Shock. 2012;37:197–204. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31823f19a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai W, Wang Y, Lin JY, Sun XD, Yao LN, Yang YH, et al. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects against traumatic hemorrhagic shock via attenuation of oxidative stress. J Surg Res. 2011;176:210–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HD, Zhang ZR, Zhang QX, Qin ZC, He DM, Chen JS. Treatment with exogenous hydrogen sulfide attenuates hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury in mice. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:1555–63. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2584-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YX, Ayala A, Monfils B, Cioffi WG, Chaudry IH. Mechanism of intestinal mucosal immune dysfunction following trauma-hemorrhage: increased apoptosis associated with elevated Fas expression in Peyer's patches. J Surg Res. 1997;70:55–60. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Xu DZ, Davidson MT, Hasko G, Deitch EA. Hemorrhagic shock induces endothelial cell apoptosis, which is mediated by factors contained in mesenteric lymph. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2464–70. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000147833.51214.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N, Yonehara S, Ishii A, Yonehara M, Mizushima S, Sameshima M, et al. The polypeptide encoded by the cDNA for human cell surface antigen Fas can mediate apoptosis. Cell. 1991;66:233–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrik IN, Krammer PH. Regulation of CD95/Fas signaling at the DISC. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:36–41. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff TA, Guo RF, Neff SB, Sarma JV, Speyer CL, Gao H, et al. Relationship of acute lung inflammatory injury to Fas/FasL system. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:685–94. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar RK, Chung CS, Chen Y, Monaghan SF, Lomas-Neira J, Heffernan DS, et al. Local tissue expression of the cell death ligand, fas ligand, plays a central role in the development of extrapulmonary acute lung injury. Shock. 2011;36:138–43. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31821c236d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu FN, Zhang X, Hu XM, Chen J, Chang LL, Li JW, et al. Targeted mutation of Fas ligand gene attenuates brain inflammation in experimental stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LM, Jiang CX, Liu DW. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates neuronal injury induced by vascular dementia via inhibiting apoptosis in rats. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:1984–92. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao LL, Huang XW, Wang YG, Cao YX, Zhang CC, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis by preventing GSK-3beta-dependent opening of mPTP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1310–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00339.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Q, Zhang Y, Yu C, Liu Y, Gao L, Zhao J. Hydrogen sulfide protects against high-glucose-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2012;59:188–93. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31823b4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JM, Cory S. Bcl-2-regulated apoptosis: mechanism and therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:488–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GM. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J. 1997;326:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Pattillo CB, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:365–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]