Abstract

Cross-amplification of five Arabidopsis abiotic stress-responsive genes (AtPAP, ZFAN, Vn, LC4 and SNS) in Lepidium has been documented in plants raised out of seeds pre-treated with potassium nitrate (KNO3) for assessment of enhanced drought stress tolerance. cDNA was synthesized from Lepidium plants pre-treated with KNO3 (0.1% and 0.3%) and exposed to drought conditions (5% and 15% PEG) at seedling stage for 30 d. Transcript accumulation of all the five genes were found suppressed in set of seedlings, which were pre-treated with 0.1% KNO3 and were exposed to 15% PEG for 30 d. The present study establishes that different pre-treatments may further enhance the survivability of Lepidium plants under conditions of drought stress to different degrees.

Keywords: pre-germination treatment, seed dormancy, Lepidium latifolium, drought stress, polyethylene glycol

Introduction

The genus Lepidium is one of the largest genera of the monophyletic Brassicaceae family with more than 150 species distributed worldwide.1 Lepidium latifolium (commonly called as Pepperweed, Pepperwort or Peppergrass) is an invasive plant2 of western Asia and southeastern Europe and currently distributed from Norway in the west to up to western Himalayas in the east.3 In high-altitude cold-arid Ladakh area of Western Himalayas, leaves of Lepidium latifolium are consumed as vegetable and salad by the natives.4 In addition to its agronomic, economic and ecological importance, Lepidium is also known for its high medicinal value and used in treatment of stomach related disorders.5

Each mature plant of Lepidium produces thousands of seeds each year,6 however only a small percentage of seeds survive.7 The inherent dormancy in the Lepidium seeds further delays the onset of advanced generation by a few months. Dormancy may be exogenous or endogenous in nature and a number of molecular to environmental signals may be required to overcome it. However, several physio-chemical pre-germination treatments are known that can break the dormancy by acting as direct or indirect artificial endo/exogenous signals for seed germination.8 Interestingly, most of these methods are simple, low-cost and can be handled by relatively unskilled manpower. Seed pre-treatments not only improve seed germination rate, they also result into faster and synchronous seed germination and have often reported to improve the matured plant’s ability to tolerate environmental stress.9 Lepidium, despite its occurrence in conditions of abiotic stress, has escaped the focus of the scientific community. Till date, there are only a few reports on Lepidium pre-germination seed treatments10-12 or characterization of the stress responsive genes.4,13-15 To improve the efficiency of seed germination and characterize the gene expression behavior of Lepidium plants away from their natural habitat, we have applied a number of seed pre-treatments and subsequently assessed the performance of plants under drought stress conditions. As little molecular data of Lepidium exists in public domain, known stress responsive genes from Arabidopsis thaliana have been cross-amplified in Lepidium.

Results and Discussion

Pre-treatments

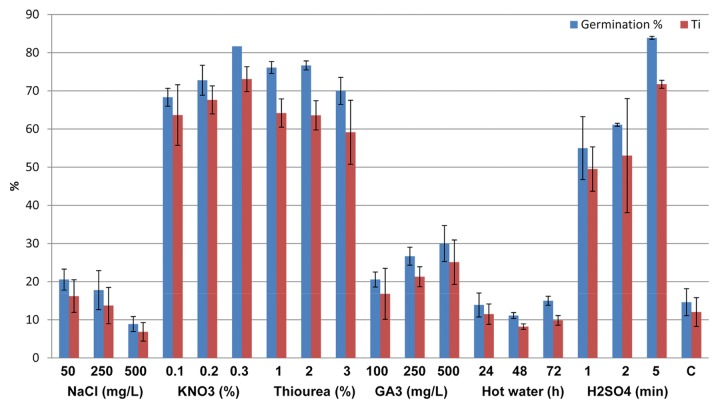

Pre-treatments were classified on the lines of types of dormancy. Certain treatments like ionic solutions, salts, acids, etc. are primarily used to overcome exogenous dormancy, while phytohormones like GA3, hot and cold water stratifications were generally used to overcome endogenous dormancy. Among the various methods used to overcome exogenous dormancy, seed pre-treatment with salts could improve seed germination rates, as they stick to cell surfaces and thereby induce osmotic pressure on the cytosol.16 Most saline pre-treatments of the seeds have been based on NaCl and KNO3.8,17,18 We found that concentrations of KNO3 improved both seed germination by 5-fold, as well as the germination velocity (Timson’s index) in comparison to control (Fig. 1). Timson’s index is effective in evaluation of germination considering the time to 50% germination and the final percentage of germination obtained. Pre-treatments with NaCl (50 and 250 mg/L) did not show any major improvement in the germination percentage and seed treatment with 500 mg/L NaCl had rather a negative effect on seed germination. In a previous study from this laboratory, effects of thiourea treatments on germination percentage were found comparable to KNO3 treatments8 on seeds of Hippophae salicifolia. The same has been found true in the present study for Lepidium latifolium as well (Fig. 1). However, the germination velocity was more profound in case of KNO3 treatment as compared with thiourea treatments. Pre-soaking of Lepidium seeds in 98% H2SO4 for 5 min was found as the best pre-germination treatment in terms of obtaining the highest germination percentage (Fig. 1). Shorter soaking times in 98% H2SO4 i.e., 1–2 min. had lesser effect on improvement of germination percentage.

Figure 1. Germination percentage and Timson Index (Ti) of Lepidium latifolium L. seeds as influenced by various pre-sowing seed priming treatments including NaCl (50, 250, 500 mg/L), KNO3 (0.1, 0.2, 0.3%), thiourea (1, 2, 3%), GA3 (100, 250, 500 mg/L), hot water (65°C) stratifications (24, 48, 72 h) and sulphuric acid (98% for 1, 2 and 5 min). A set of seeds without pre-sowing treatments was considered as control (C).

For many species, the seeds buried under soil germinate by themselves after remaining dormant for a particular season i.e., winter or summer months, as part of their seasonal patterns of dormancy behavior.7 Such seeds show a form of dormancy called as endogenous dormancy, which is either controlled by environmental signals or by relative levels of phytohormone concentrations inside the cells. In laboratory, these conditions can be easily mimicked by soaking the seeds in hot or cold water. Alternatively, applications of phytohormones may produce the desired effect. In the present study, hot water treatments had no positive effect on seed germination (Fig. 1) and cold water treatments completely inhibited the seed germination, which strongly suggested that dormancy in Lepidium is controlled by exogenous factors and there is little, if at all, effect of high or low temperatures under natural conditions.12 Our results were further strengthened by the observation that different GA3 concentrations had relatively small effect on seed germination (Fig. 1).

Morphometric analysis of drought stress tolerance

Among all the treatments described above, concentrations of KNO3 made most uniform impact on the germination characteristics of Lepidium seeds. It is well established that its application impact the performance of plants in a positive manner and also increase their water use efficiency (WUE).19,20 We transplanted the plantlets obtained after KNO3 treatment to pots filled with vermiculite and further assessed for their ability to tolerate drought stress. From each set of KNO3 treated seedlings, three subsets were subjected to drought stress by 5 and 15% PEG. A control set of equal number of seedlings were irrigated with distilled water. These conditions were maintained for 15 d, after which further subsets were drawn and exposed to 5 or 15% PEG and control subset irrigated with water for another 15 d, as detailed in Figure 1. The state of survivability of the plants was assessed based on leaf counts and the lengths of their midribs. The control set (Experimental set up series 1; Table 1) did not either survive the duration of the experiment or wherever some plants survived, they showed stunted growth. Interestingly, plants showed better adaptability to stress in initial period of stress after transplanting. As the latter 15 d stress of 5% PEG only seemed to have been acclimated by the plants (Table 1). The behavior of plants in terms of elongation of aerial parts in response to increasing PEG concentrations vary with species and evidences exist that point such responses to be age-dependent as well.21 While certain plants like tomato show positive correlation with increase in lengths of aerial parts under increasing PEG concentrations,22 others like salvia show negative correlation.23 Interestingly, in case of Lepidium, 5% PEG treatments showed increase in shoot length, but higher concentrations resulted in antagonist response. In general, the drought stress inhibits cell enlargement and affects various physiological and biochemical processes.21 Among different concentrations of seed pre-treatments, 0.1% KNO3 primed seeds showed better adaptability to drought stress in later stages.

Table 1. Pre-Treatment of Lepidium seeds and subsequent exposure to drought stress.

| Pre germination Treatment | Post-transplant treatment- 1 (1–15 d) |

Post-transplant treatment- 2 (16–30 d) |

Performance | Experimental set up No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | H2O | H2O | Death | 1.1.1 | ||

| 5% PEG | Stunted growth | 1.1.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Stunted growth | 1.1.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 1.1.4 | ||||

| 5% PEG | H2O | Death | 1.2.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | 1.2.2 | |||||

| 15% PEG | 1.2.3 | |||||

| 30% PEG | 1.2.4 | |||||

| 15% PEG | H2O | Death | 1.3.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | Stunted growth | 1.3.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Stunted growth | 1.3.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 1.3.4 | ||||

| 0.1% KNO3 | H2O | H2O | Good growth | 2.1.1 | ||

| 5% PEG | Good growth | 2.1.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Stunted growth | 2.1.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 2.1.4 | ||||

| 5% PEG | H2O | Good growth | 2.2.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | Good growth | 2.2.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Stunted growth | 2.2.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 2.2.4 | ||||

| 15% PEG | H2O | Good growth | 2.3.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | Death | 2.3.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Stunted growth | 2.3.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 2.3.4 | ||||

| 0.2% KNO3 | H2O | H2O | Good growth | 3.1.1 | ||

| 5% PEG | Good growth, but poor health | 3.1.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Good growth, but poor health | 3.1.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 3.1.4 | ||||

| 5% PEG | H2O | Death | 3.2.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | 3.2.2 | |||||

| 15% PEG | 3.2.3 | |||||

| 30% PEG | 3.2.4 | |||||

| 15% PEG | H2O | Death | 3.3.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | 3.3.2 | |||||

| 15% PEG | 3.3.3 | |||||

| 30% PEG | 3.3.4 | |||||

| 0.3% KNO3 | H2O | H2O | Good growth | 4.1.1 | ||

| 5% PEG | Good growth, but poor health | 4.1.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Good growth, but poor health | 4.1.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 4.1.4 | ||||

| 5% PEG | H2O | Good growth | 4.2.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | Good growth, but poor health | 4.2.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Stunted growth | 4.2.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 4.2.4 | ||||

| 15% PEG | H2O | Good growth | 4.3.1 | |||

| 5% PEG | Stunted growth | 4.3.2 | ||||

| 15% PEG | Death | 4.3.3 | ||||

| 30% PEG | Death | 4.3.4 | ||||

Note: The visible inspection of “good growth” and “stunted growth” is relative to each other. A statistically significant difference of average length of midrib of longest leaf > 7 cm was called “good growth”, while average length of midrib of longest leaf < 5 cm was called “stunted growth.” In none of the data sets, average lengths of midrib of longest leaves were found in the range 5–7 cm.

“Poor health” describes the condition of relatively more number of yellowing and senescent leaves on average in a particular data set compared with healthy and green leaves.

Molecular analysis of drought stress tolerance

Drought is a complex stress, in whose response many bio-molecules interact including nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, hormones, free radicals, etc. In fact, drought affects almost all aspects of plant cell metabolism. As the plant responses to different stresses have cross-talk among themselves at more than one level of metabolism, studies targeted onto any one may have direct implications in understanding other stresses as well.24 Evidences exist, wherein drought stress has been found related to stresses caused by salinity, temperature extremes, pH extremes, pathological reactions, senescence, growth, development, UV-B damage, wounding, embryogenesis, flowering, signal transduction and so on.25 Thus, the signals of water scarcity drive the regulation of a number of plant genes. A good number of the genes are induced within a few minutes of receiving the signal and have been called as “early responsive genes.” Transcription factors that further effect expression of other genes are mostly categorized into this category. The late or delayed responsive genes, in contrast are activated by stress more slowly and their expression is sustained. Fourteen primer pairs were designed for known stress responsive genes in Arabidopsis to amplify homologous genes in closely related Lepidium. Five of these genes, i.e., zinc finger protein coding gene (ZFAN), LHCA4 (LC4) encoding PSI type IV chlorophyll in Arabidopsis, vernalization related gene (Vn), plastid lipid associated protein (AtPAP) and senescence related gene (SNS), were successfully amplified in Lepidium. In order to assess the efficiency with which KNO3 treated plants acclimatize to varying degrees of drought stress, the expression levels of each of these five genes were studied based on end-point fluorescence and using cDNA from ten experimental set ups exposed to varying degrees of stress.

The zinc finger protein coding gene (ZFAN) acts as a transcription repressor during abiotic stress and is an early responsive gene. The effect of 0.3% KNO3 could be clearly seen in the ability of the plants to accumulate its transcripts during drought stress induced by PEG treatments (Table 2). The vernalization (Vn) and LC4 genes, known to be responsive to cold stress, were found to have no significant differential expression in response to the drought stress. Only a minute amount of transcript accumulation was recorded for Vn gene in the plants matured out of 0.3% KNO3 treated seeds, whereas, no net significant difference could be observed in accumulation of LC4 gene in differently treated plants samples under study. AtPAP is known to get up-regulated during abiotic stress. Interestingly, we observed that this gene overexpressed by three times in the plants maturing out of 0.3% KNO3 treated seeds compared with the plants that were matured out of 0.1% KNO3 treated seeds (Table 1). However, in a given set of water vs. PEG treatment analysis, no change could be observed in the finally accumulated amplified transcripts. SNS is expected to get up-regulated during the stress, but its expression was found more or less constant in all the samples (Table 2).

Table 2. Transcript accumulation of abiotic stress related genes in response to different post-transplant treatments.

| Pre-germination Treatment | Post-transplant treatment-1 (1–15 d) |

Post-transplant treatment-2 (16–30 d) |

Transcript Accumulation (Folds) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtPAP | SNS | ZFAN | Vn | LC4 | |||

| 0.1% KNO3 | H2O | H2O | 1.00 | 1.01 | 2.37 | 0 | 1.01 |

| 15% PEG | 0.83 | 0.99 | 1.62 | 0 | 1.00 | ||

| 5% PEG | H2O | 0 | 1.05 | 1.59 | 0 | 1.11 | |

| 15% PEG | 0.87 | 0.98 | 1.56 | 0 | 1.12 | ||

| 15% PEG | H2O | 1.68 | 1.27 | 1.96 | 0 | 1.21 | |

| 15% PEG | 0 | 1.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.93 | ||

| 0.3% KNO3 | H2O | H2O | 0 | 0.92 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15% PEG | 2.97 | 1.26 | 3.39 | 0.28 | 1.21 | ||

| 5% PEG | H2O | 2.52 | 1.22 | 0.90 | 0.16 | 1.02 | |

| 15% PEG | 2.75 | 1.05 | 3.61 | 0.21 | 1.26 | ||

Actin transcript accumulation was recorded 41.21 ng under control conditions.

The abilities of the plants to perform well under stress after treatment with KNO3 might have a direct relation with the plant’s ability to utilize the constituent ions (K+ and NO3−) separately. At cellular level, Potassium (K+) substantially affects enzyme activation, protein synthesis, photosynthesis, stomatal movement and water-relation (turgor regulation and osmotic adjustment), signal transduction, intracellular movement of macromolecules (especially sugars) and many other processes.26 It is known to enhance plant growth, yield and drought resistance in different crops under water stress conditions.27-30 Further, Nitrate ions promote water use efficiency (WUE), photosynthesis and biomass production rates.31 Applied together, potassium and nitrate ions produce synergistic effect,32 enhancing survival of seeds and subsequent drought tolerance.

Pre-treatment of Lepidium seeds with KNO3 (0.1–0.3%) has thus been found an effective method to enhance the germination percentage and ensure its growth under arid conditions. For a cold arid climate like that of Ladakh, where Lepidium leaves are cooked as vegetables, such practices might be important to ensure the availability of food material for the local population. Similar applications in other food crops can also be applied to ensure their harvest even under conditions of water deficiency, especially in countries with lesser acceptability of genetically modified crops and foods.

Material and Methods

Pre-germination treatments

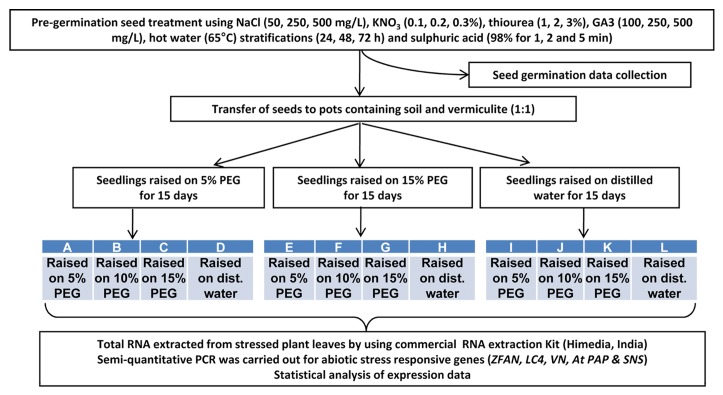

Mature seeds of Lepidium latifolium L. were collected from Leh, India (34° 8′ 43.43ʺ N, 77° 34ʹ 3.41ʺ, 3505 m asl) and transported to our laboratory in Haldwani, India (29° 13ʹ 11.946ʺ N, 79° 31ʹ 11.9244ʺ E, 443 m asl) in zip lock bags. Seeds were disinfected by immersing in 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 min followed by rinsing thoroughly with distilled water four times. Various pre-treatments, as described earlier8 and depicted in Figure 2 were performed in triplicate sets of 60 seeds each. Emergence of radicle was recognized as the event of seed germination and the plants were grown for 30 d in 16/8 h light/dark cycle at 25°C. Besides final germination percentages, the rate of germination (or germination velocity) was also calculated according to a modified Timson’s velocity index or Timson Index32: ΣG/T, where “G” is the percentage of seeds germinated after 2 d interval and “T” is the total time of germination. The overall line of work is described in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Experimental out line of pre- and post-germination treatments in Lepidium latifolium.

Analysis of gene expression

Primers of 14 genes (Table 3) from Arabidopsis were used in PCR with cDNA of Lepidium latifolium as template. Out of these, five genes were amplified successfully, which were assessed further using semi-quantitative PCR analysis to study transcript accumulation. Actin gene was used as an internal control for assessment of differential regulation of the five genes under analysis.

Table 3. List of primers used for cross-amplification of Arabidopsis genes and in semi quantitative transcript accumulation of different abiotic stress responsive genes.

| Gene name | Description | Forward Primer (5′-3′) Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| CABP | Calcium binding protein coding gene | ATGAAGGGGA GGATTTCGAA G TCATGAAACC AACTGAGAGC |

| ZFAN | Zinc finger protein coding gene | AGTGGCTCAG AGGAAAACAA CTCA AATCCTCTGA ACTTTATCC |

| CAL | Calcinurin like gene | ATGAAGGATC CGAAACTAAG TTAGTCGATC TCCACAATTT GA |

| LC4 | LHCA4 gene encodes the photosystem 1 type IV chlorophyll a/b-binding protein complex | ATGGCTACTG TCACTACTCA TGTTA GCCTCTGAGA GTCTGGAC |

| SEN | Senescence related gene | CCTCTCGAAT CTGCTTTTCG CAGTC GCCAGGACGA GAGTTCCTGT CCGT |

| LEY | Leafy gene | ATGGATCCTG AAGGTTTCAC CAG CAGAGCTCCT AGAATCGCAA AGTCGTCG |

| ZIP | Zinc transporter gene | CCTGAGGGAA AATGCAGAC CCGAGAAATC CCCTCGAAGA |

| SDR | Short chain dehydrogenase related gene | TGGATGGTGC TGGCTCTGGA CTCGTCCTGT TCTCTGCCCA GTTCC |

| VN | Vernalization related gene | ATGTGTAGGC AGAATTGTCG C TTACTTGTCT CTGCTGTTAT TG |

| At PAP | Plastid Lipid associated protein coding gene | TTGCGGCATT TAGATTCTCC AGCT AAATTTCTCG GATGTGCAC |

| SNS | Senescence related gene | ATGGCTTCGT ATTACTCTGG T CTAAGCCACG ACGAGAGTTC |

| AP2 | APE2 transporter gene | ATGGAGTCAC GCGTGCTGT TCAGCTGCTT TCTATGCTTT C |

| C4 | Cbf4 gene | ATGAATCCAT TTTACTCTAC ATTCC TTACTCGTCA AAACTCCAGA GTC |

| SK | Serine/Threonin kinase gene | ATGACTGATG AGGTAGACGG TTAGTCGAAG CTCGAAGAAC G |

The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 25 µl, which was constituted of 10 pmol of gene-specific primers (Table 2), 20 µM of dNTPs mix, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1× Taq polymerase buffer and 1U Taq polymerase (Genei, Merck Millipore). Thermal cycling conditions constituted of initial denaturation of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, re-annealing for 30 sec at 55°C followed by elongation at 72°C for 30 sec. A final elongation for 5 min was performed at 72°C. Amplicons were run on 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide (0.1 ppm) in 1× TAE buffer. The gel was documented on a phosphoimager (Typhoon Trio+ Imagers, GE Healthcare) and analyzed using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). Molecular sizes and their quantities were calibrated against the known values of various DNA bands of the GeneRuler™ 100 bp Plus ladder (Fermentas). The background intensity of the gel material was suitably subtracted prior to analysis.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Dr Mukesh Jain, National Institute of Plant Genome Research (NIPGR), New Delhi for critical improvements in the manuscript and his valuable suggestions. Sadhana Singh and Pankaj Pandey acknowledge Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) for research fellowships.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/25388

References

- 1.Mummenhoff K, Brüggemann H, Bowman JL. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny and biogeography of Lepidium (Brassicaceae) Am J Bot. 2001;88:2051–63. doi: 10.2307/3558431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds LK, Boyer KE. Perennial pepperweed (Lepidium latifolium): properties of invaded tidal marshes. Inv. Plant Sci. Manage. 2010;3:130–8. doi: 10.1614/IPSM-D-09-00015.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover A, Gupta SM, Pandey P, Singh S, Ahmed Z. Random genomic scans at microsatellite loci for genetic diversity estimation in cold adapted Lepidium latifolium. Plant Genetic Resour. 2012;10:224–31. doi: 10.1017/S1479262112000299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta SM, Grover A, Ahmed Z. Identification of abiotic stress responsive genes from Indian high altitude Lepidium latifolium L. Def Sci J. 2012;62:315–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martínez Caballero S, Carricajo Fernández C, Pérez-Fernández R. Effect of an integral suspension of Lepidium latifolium on prostate hyperplasia in rats. Fitoterapia. 2004;75:187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howald A. Lepidium latifolium L. In: Bossard CC, Randall JM, Hoshovsky MC, eds. Invasive plants of California's wildlands. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000; 222-227. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batlla D, Benech-Arnold LR. Predicting changes in dormancy level in weed seed soil banks: Implications for weed management. Crop Prot. 2007;26:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2005.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta SM, Pandey P, Grover A, Ahmed Z. Breaking seed dormancy in Hippophae salicifolia, a high value medicinal plant. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2011;17:403–6. doi: 10.1007/s12298-011-0082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farooq M, Basra SMA, Wahid A, Ahmad N, Saleem BA. Induction of drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) by exogenous application of salicylic acid. J Agron Crop Sci. 2009;195:237–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2009.00365.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller GK, Young JA, Evans RA. Germination of seeds of perennial pepperweed (Lepidium latifolium) Weed Sci. 1985;34:252–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang A-J, Tian M-H, Long C-L. Dormancy and germination in short-lived Lepidium perfoliatum L. (Brassicaceae) seed. Pak J Bot. 2010;42:201–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karimmojeni H, Rashidi B, Behrozi D. Effect of different treatments on dormancy-breaking and germination of perennial pepperweed (Lepidium latifolium) (Brassicaceae) Aust. J. Agric. Engg. 2011;2:50–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aslam M, Sinha VB, Singh RK, Anandhan S, Pande V, Ahmed Z. Isolation of cold stress responsive genes from Lepidium latifolium by suppressive subtraction hybridization. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32:205–10. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0382-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslam M, Grover A, Sinha VB, Fakher B, Pande V, Yadav PV, et al. Isolation and characterization of cold responsive NAC gene from Lepidium latifolium. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:9629–38. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta SM, Pandey P, Negi PS, Pande V, Grover A, Patade VY, et al. DRE-binding transcription factor gene (LlaDREB1b) is regulated by various abiotic stresses in Lepidium latifolium L. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:2573–80. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2343-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobe K, Xiaoming L, Omasa K. Effects of five different salts on seed germination and seedling growth of Haloxylon ammodendron (Chenopodiaceae) Seed Sci Res. 2004;14:345–53. doi: 10.1079/SSR2004188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yücel E, Yilmaz G. Effects of different alkaline metal salts (NaCl, KNO3), acid concentrations (H2SO4) and growth regulator (GA3) on the germination of Salvia cyanescens Boiss. & Bal. seeds. G. U. J. Sci. 2009;22:123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramzan A, Hafiz IA, Ahmad T, Abbasi NA. Effect Of priming with potassium nitrate and dehusking on seed germination of gladiolus (Gladiolus Alatus) Pak J Bot. 2010;42:247–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fournier JM, Roldán A, Sánchez C, Alexandre G, Benlloch M. K+ starvation increases water uptake in whole sunflower plants. Plant Sci. 2005;168:823–9. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benlloch-González M, Arquero O, Fournier JM, Barranco D, Benlloch MK. K(+) starvation inhibits water-stress-induced stomatal closure. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165:623–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaleel CA, Manivannan P, Wahid A, Farooq M, Somasundaram R, Panneerselvam R. Drought stress in plants: a review on morphological characteristics and pigments composition. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2009;11:100–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamwal A, Puri S, Sharma S, Bhattacharya S. Impact of water-deficit stress on the seed germination and growth of Lycopersicon esculentum ‘Solan Sindhur’. NeBIO. 2012;3:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnett SE, Pennisi SV, Thomas PA, Van-Iersel MW. Controlled drought affects morphology and anatomy of Salvia splendens. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2005;130:775–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakashima K, Ito Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in response to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis and grasses. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:88–95. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni F-T, Chu L-Y, Shao H-B, Liu Z-H. Gene expression and regulation of higher plants under soil water stress. Curr Genomics. 2009;10:269–80. doi: 10.2174/138920209788488535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marschner H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants. 2nd Ed. Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma KD, Nandwal AS, Kuhad MS. Potassium effects on CO2 exchange, ARA and yield of clusterbean cultivars under water stress. J. Pot. Res. 1996;12:412–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiwari HS, Agarwal RM, Bhatt RK. Photosynthesis, stomatal resistance and related characters as influenced by potassium under normal water supply and water stress conditions in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Ind. J. Plant Physiol. 1998;3:314–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav DS, Goyal AK, Vats BK. Effect of potassium in Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn. under moisture stress conditions. J. Pot. Res. 1999;15:131–4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng Y, Jia A, Ning T, Xu J, Li Z, Jiang G. Potassium nitrate application alleviates sodium chloride stress in winter wheat cultivars differing in salt tolerance. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165:1455–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kattimani KN, Reddy YN, Rao RB. Effect of presoaking seed treatment on germination, seedling emergence, seedling vigour and root yield of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera Daunal.) Seed Sci. Technol. 1999;27:483–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Timson J. New method of recording germination data. Nature. 1965;207:216–7. doi: 10.1038/207216a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]