Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of highly conserved germline-encoded pattern-recognition receptors that are essential for host immune responses. TLR ligands represent a promising class of immunotherapeutics or vaccine adjuvants with the potential to generate an effective antitumor immune response. The TLR7/8 agonists have aroused interest because they not only activate antigen-presenting cells but also promote activation of T and natural killer (NK) cells. However, the exact mechanism by which stimulation of these TLRs promotes immune responses remains unclear, and different TLR7/8 agonists have been found to induce different responses. In this study, we demonstrate that both gardiquimod and imiquimod promote the proliferation of murine splenocytes, stimulate the activation of splenic T, NK and natural killer T (NKT) cells, increase the cytolytic activity of splenocytes against B16 and MCA-38 tumor cell lines, and enhance the expression of costimulatory molecules and IL-12 by macrophages and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCs). In a murine model, both agonists improved the antitumor effects of tumor lysate-loaded DCs, resulting in delayed growth of subcutaneous B16 melanoma tumors and suppression of pulmonary metastasis. Further, we found that gardiquimod demonstrated more potent antitumor activity than imiquimod. These results suggest that TLR7/8 agonists may serve as potent innate and adaptive immune response modifiers in tumor therapy. More importantly, they can be used as vaccine adjuvants to potentiate the efficiency of DC-based tumor immunotherapy.

Keywords: antitumor therapy, DC vaccine, melanoma, TLR, TLR7/8 agonist

Introduction

Innate immunity plays a major role in the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns via pattern-recognition receptors and in the elimination of foreign pathogens and tumor cells, both by direct killing and by activating the adaptive immune system.1, 2 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are an important family of pattern-recognition receptors with at least 11 members.3, 4 TLR7 and TLR8 are localized to endosomes and recognize single-stranded RNA, resulting in the activation of NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinase and other signaling pathways. This leads to the to secretion of cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-α and tumor-necrosis factor-α.5, 6, 7 TLR ligands represent a promising class of immunotherapeutics or vaccine adjuvants with the potential to generate an effective antitumor immune response.8

Recognition of TLR7 ligands by TLR7 leads to the overall activation and maturation of antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFN. After recognition of TLR7 ligand, mature DCs are able to fully activate effector T cells and drive more potent immune responses.9, 10 Imiquimod (R837) is a small molecular compound in the imidazoquinoline family that exerts antiviral and antitumor effects.11, 12 Imiquimod has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating external genital and perianal warts and is also used for treatment of malignant tumors of the skin.13 Imiquimod was recently shown to preferentially bind to TLR7 and, to a lesser extent, TLR8. Gardiquimod is a new imidazoquinoline compound developed and manufactured by InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA). Like imiquimod, gardiquimod induces the activation of NF-κB in HEK293 cells expressing human or mouse TLR7; however, gardiquimod is 10 times more active than imiquimod and has been proven to bind specifically to TLR7 and TLR8. In this study, we observed the effects of imiquimod and gardiquimod on the activation of splenocytes and the inhibition of murine B16 melanoma growth and metastasis.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The murine melanoma cell line B16, the murine colon adenocarcinoma cell line MCA-38 and the murine macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 (preserved in our lab) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco/BRL, Grand Island, NY , USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Mice

Six- to eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice weighing 20–24 g were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The mice were maintained and fed under specific pathogen-free conditions in our facility. Animal care and experimental procedures were performed according to specific pathogen-free.

Reagents and antibodies

Imiquimod and gardiquimod were synthesized by InvivoGen, formulated in endotoxin-free water, and stored at −20 °C. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5.5-labeled antimouse CD3 and FITC-labeled antimouse natural killer (NK) 1.1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were purchased from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). PE-labeled antimouse CD69, FITC-labeled antimouse CD40, FITC-labeled antimouse CD80 and PE-labeled antimouse CD86 mAbs were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA).

Cell proliferation assay

Proliferation was determined by culturing 5×104 freshly isolated splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice with different doses of imiquimod or gardiquimod in 96-well plates for 48 h. 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (20 µl, 5 mg/ml) was added 4 h before the end of the incubation period. Dimethylsulfoxide was used to dissolve granules, and the absorbance (A) at 570 nm of each sample was determined with a microplate autoreader (BIO-RAD Model 680 BioRad, Pleasanton, CA, USA). The proliferation rate was determined as follows: (A of treatment group/A of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) group)×100%.

Cytolytic assays

The cytolytic activity of splenic NK cells was assessed by the MTT method. Briefly, the B16 cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 at a concentration of 5×104/ml and seeded into 96-well plates (100 µl/well). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The splenocytes were first treated with 1 µg/ml gardiquimod or imiquimod for 48 h and then washed and added to target cells at effector/target ratios of 40:1, 20:1, 10:1 or 5:1. The cell mixtures were incubated for 24 h, and 20 µl MTT (5 mg/ml) was added 4 h before the end of the incubation period. The remaining formazan precipitate was thoroughly dissolved in 200 ml dimethylsulfoxide, and the absorbance (A) at 570 nm of each sample was determined with a microplate autoreader (BioRad). The degree of cytotoxicity was calculated as follows: % lysis=[1−(A of cocultured cells−A of effector cells)/A of target cells]×100%.

Flow cytometry analysis

Murine splenocytes were treated with imiquimod or gardiquimod or left untreated and stained with FITC-labeled anti-NK1.1, PE-Cy5.5-labeled anti-CD3 and PE-labeled anti-CD69 mAbs. RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells and DCs were stained with FITC-labeled antimouse CD40, FITC-labeled antimouse CD80 or PE-labeled antimouse CD86 mAb. Cells were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and analyzed using WinMDI 2.9 software.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from lymphocytes and RAW264.7 cells with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was generated with random primers and moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was quantified by real-time PCR analysis. PCR primers specific for IFN-γ, NKG2D, FasL and perforin were designed by Invitrogen. The sequences were as follows: β-actin, forward 5′-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′, reverse 5′-CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′ FasL, forward 5′-TGGGTAGACAGCAGTGCCAC-3′, reverse 5′-GCCCACAAGATGGACAGGG-3′ NKG2D, forward 5′-TTCACCCTTAACACATTGATG-3′, reverse 5′-GGGACTTCCTTGTTGCACAATAC-3′ perforin, forward 5′-CACAGTAGAGTGTCCGATGT-3′, reverse 5′-CTTGGTTCCCGAAGAGCAGAT-3′ IFN-γ, forward 5′-AGCGGCTGACTGAACTCAGATTGTAG-3′, reverse 5′-GTCACAGTTTTCAGCTGTATAGGG-3′ IL-12 p40, forward 5′-AGAGGAGGGGTGTAACCAG-3′, reverse 5′-GGGAACACATGCCCACTTG-3′. PCR reactions were carried out using SYBR Green Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). β-actin was used as an internal control.

Cytokine assays

The level of IL-12 in cell culture supernatants was determined using standard sandwich ELISA Kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation of tumor cell lysates

Murine melanoma B16 cells were collected, washed twice with 1× PBS, and resuspended at a density of 4×106/ml in PBS. The suspended cells were frozen at −80 °C and disrupted by five freeze–thaw cycles. The lysate was then centrifuged for 15 min at 4000g. The supernatant was collected and passed through a 0.2-μm filter. The protein concentration of the lysate was determined by Bradford assay.

Bone marrow-derived DCs

Bone marrow cells from femurs and tibiae were cultured in six-well plates in 10 ml (1×106 cells/ml) of RPMI-1640 medium for 4 h. Non-adherent cells in the culture were discarded, and fresh RPMI-1640 medium containing 40 ng/ml murine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Peprotech, London, UK) and 100 ng/ml IL-4 (Peprotech) was added to the adherent cells. Non-adherent cells in the culture were discarded again on days 3 and 5. On day 3, 5 ml of fresh medium was added; on day 5, 5 ml of medium was replaced with fresh medium. On day 6, the cells were incubated with B16 cell lysate at a concentration of 100 µg protein/ml for 16 h. DCs were collected and used on day 7. The proportion of DCs in the culture was consistently >90% as determined by flow cytometric analysis. The expression of CD11c and MHC-II was also assessed.

Tumor challenge and treatment

For subcutaneous (s.c.) tumors, 5×104 B16 cells in 100 µl of PBS were injected s.c. into the right flank of C57BL/6 mice on day 0. Mice were vaccinated intravenously with 4×104 DCs on day 7 and peritumorally injected with 1 mg/kg either imiquimod or gardiquimod on days 8 and 10. Control mice were injected with an equivalent volume of PBS. Beginning on day 8, the tumor length and width were measured with a vernier caliper, and tumor volume was calculated as length×width2/2. The mice were killed on day 13, and tumors were excised and weighed. For lung metastatic tumors, 1×106 B16 cells in 200 µl of PBS were injected into the tail vein. For tumor treatment, mice were injected intravenously with 4×104 DCs and 1 mg/kg either imiquimod or gardiquimod on days 7 and 10 after tumor challenge. The control group was injected with an equivalent volume of PBS. The mice were killed on day 14, and the numbers of visible melanoma metastases on the surface of lungs were counted.

Histochemical analysis

For histochemical analysis, lung or tumor tissues from tumor-bearing mice were excised on days 13 or 14, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to assess morphologic changes.

Statistical analyses

One-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences between experimental groups: *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Results

The TLR7 agonists gardiquimod and imiquimod promote proliferation, activation and cytolytic function of splenocytes

To observe the effect of TLR7 agonists on lymphocyte proliferation, murine splenocytes were treated with gardiquimod and imiquimod for 48 h. We found that both agonists promoted the proliferation of lymphocytes with a greater effect at the dosage of 1.25 µg/ml, and gardiquimod seemed to be more efficient than imiquimod (Figure 1). We thus chose a 1 µg/ml dose for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Gardiquimod and imiquimod promote proliferation of splenocytes. Freshly isolated mouse splenocytes were treated with different concentrations of gardiquimod or imiquimod for 48 h, and their proliferation rate was detected by MTT assay. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared to the untreated control. MTT, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

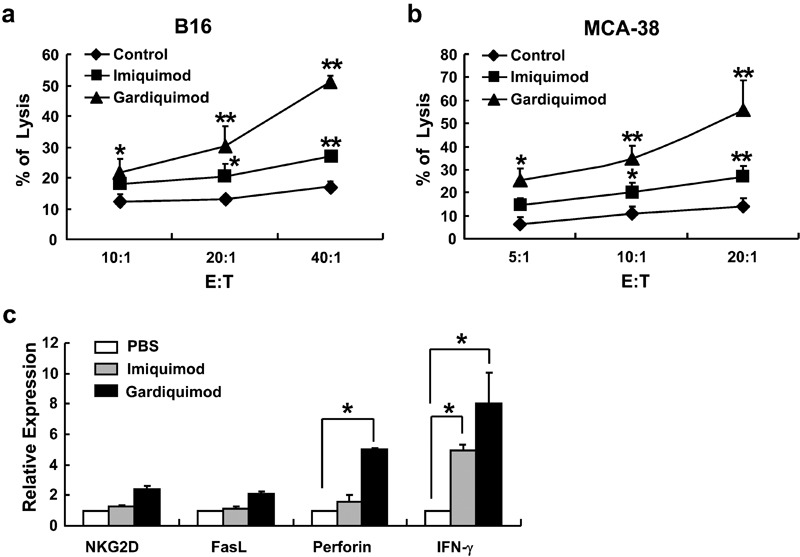

We further observed whether these agonists could enhance the activation of splenocytes by culturing lymphocytes with 1 µg/ml imiquimod or gardiquimod for 24 h and analyzing CD69 expression by flow cytometry. The results showed that treatment with imiquimod or gardiquimod resulted in significant increases in expression of CD69 on T, NK and natural killer T (NKT) cells (Figure 2). We next assessed the cytotoxic capacity of splenocytes against B16 melanoma cells. As shown in Figure 3a, both agonists augmented the cytotoxicity of splenic cells at different effector/target ratios. Gardiquimod exerted a more significant effect, and the enhancement of cytolysis was more obvious at higher effector/target ratios. Similar results were obtained using the MCA-38 murine colon adenocarcinoma cells as target cells (Figure 3b). Gardiquimod treatment enhanced the expression of the cytotoxic effector molecules perforin and IFN-γ, and imiquimod increased the expression of IFN-γ by splenocytes as determined by real-time PCR; however, the expression levels of FasL and NKG2D receptor were not changed (Figure 3c).

Figure 2.

Gardiquimod and imiquimod enhance the activation of splenocytes. (a) Freshly isolated murine splenocytes were treated with 1 µg/ml gardiquimod or imiquimod for 24 h. The expression of CD69 on CD3+ T, NK1.1+ NK and CD3+ NK1.1+ NKT cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Statistical analysis of CD69 expression. Data are expressed as mean±SD from at least three independent experiments. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, compared to the PBS treatment group. NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Figure 3.

Gardiquimod and imiquimod increase the cytotoxicity of splenocytes. Murine splenocytes were first cultured with 1 µg/ml gardiquimod or imiquimod or PBS for 48 h, and their cytotoxicity against (a) B16 melanoma cells or (b) MCA-38 cells was detected. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, compared to the PBS treatment group. (c) Splenocytes were cultured with gardiquimod or imiquimod for 24 h, and mRNA expression levels of NKG2D, FasL, perforin and IFN-γ were examined by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as mean±SD of values from at least three independent experiments. *P<0.05, compared to the PBS treatment group. E:T, effector/target ratio; IFN, interferon; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

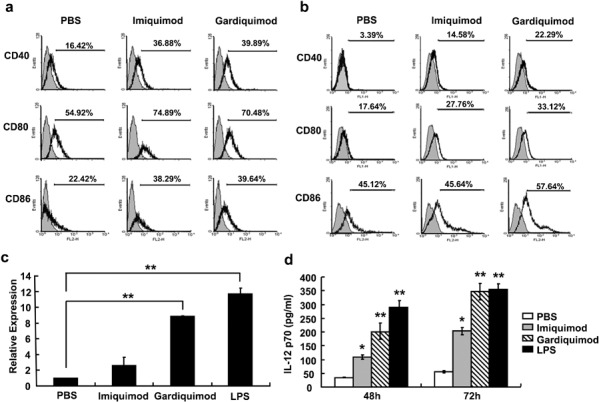

Gardiquimod and imiquimod promote the expression of costimulatory molecules on macrophages and DCs

To investigate whether these TLR7 agonists activated antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and DCs, which are believed to express high levels of TLRs and play significant roles in the activation of T cells and NK cells, we detected the expression of the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86 on macrophages and bone marrow-derived DCs in vitro. RAW264.7 murine macrophages were treated with 1 µg/ml imiquimod or gardiquimod for 24 h, and the expression of CD40, CD80 and CD86 was detected by flow cytometry. The results indicated that both agonists significantly enhanced the expression of these three costimulatory molecules on RAW264.7 cells (Figure 4a). Similar results were observed in bone marrow-derived DCs stimulated with these agonists (Figure 4b). We also found that gardiquimod stimulation increased mRNA expression of IL-12 p40 in RAW264.7 cells; however, the effect of imiquimod on IL-12 p40 mRNA expression was not determined (Figure 4c). Furthermore, imiquimod and gardiquimod both induced augmented secretion of IL-12 p70 into culture supernatant 48 and 72 h after treatment (Figure 4d). As expected, gardiquimod treatment induced these changes more efficiently than imiquimod. For these experiments, the TLR4 ligand LPS, which is known to activate antigen-presenting cells, was used as a positive control. As expected, LPS stimulation promoted IL-12 production at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 4c and d) and enhanced expression of costimulatory molecules (data not shown) by RAW264.7 cells. These results demonstrate that the TLR7 agonists could enhance the expression of costimulatory molecules and IL-12 by macrophages and DCs, potentially further promoting the activation and function of T and NK cells.

Figure 4.

Gardiquimod and imiquimod promote the expression of costimulatory molecules on macrophages and dendritic cells. (a) The murine macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 or (b) bone marrow cells were stimulated with 1 µg/ml gardiquimod or imiquimod for 24 h, and the expression levels of the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86 were examined by flow cytometry. (c) The mRNA expression levels of IL-12 p40 in TLR7 agonist-treated or LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells were detected by real-time PCR. (d) The protein levels of IL-12p70 in culture supernatants of RAW264.7 cells stimulated with gardiquimod, imiquimod or LPS were detected by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean±SD of values from at least three independent experiments. **P<0.01 compared to PBS treatment group. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

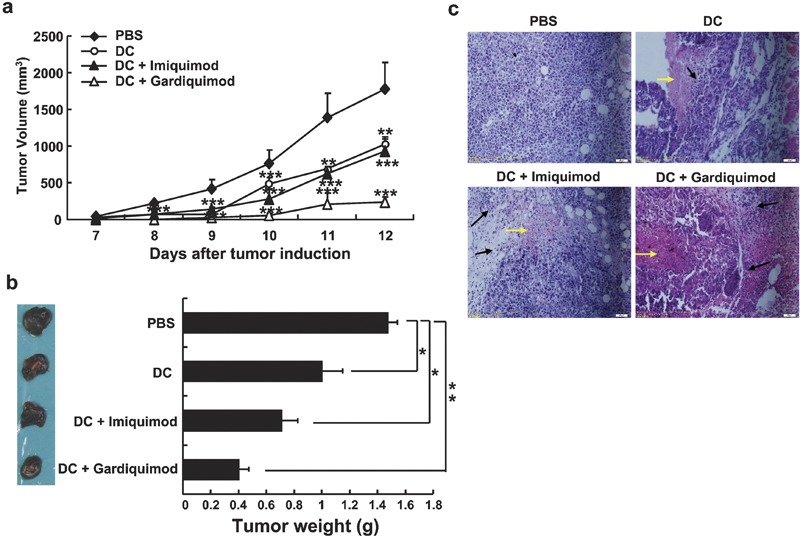

Gardiquimod and imiquimod improve the antitumor effects of tumor lysate-loaded DCs in mice

To investigate the antitumor effects of these TLR7 agonists in vivo, C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with 5×104 B16 cells, vaccinated intravenously with tumor lysate-loaded DCs on day 7, and injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg/kg TLR7 agonist on days 8 and 10. Tumor volume was calculated beginning on day 8. As depicted in Figure 5, on day 12, the tumor volume in mice injected with PBS increased to 1770±370 mm3, whereas it was only 230±70 mm3 in mice treated with gardiquimod and DC vaccine and 930±190 mm3 in mice treated with imiquimod and DC vaccine. These differences were obvious beginning on day 8. The therapeutic effect of the DC vaccine alone was similar to that of the DC vaccine combined with imiquimod (Figure 5a). Similar results were obtained by measuring tumor weight (Figure 5b). These results indicate that combining either TLR7 agonist with the DC vaccine inhibits and delays the growth of B16 melanomas and that gardiquimod exerts a more significant effect on tumor growth than imiquimod. By histochemical analysis, we observed a large number of lymphocytes infiltrating the tissue at the periphery of the tumor; we also observed significant focal necrosis in tumor tissues in mice treated with DC vaccine alone or with DC vaccine combined with gardiquimod or imiquimod (Figure 5c). These effects were more obvious in mice treated with gardiquimod combined with DC vaccine. In addition, we found that treatment with gardiquimod or imiquimod alone, or with gardiquimod or imiquimod-stimulated DCs, also exerted inhibitory effects on B16 melanoma growth in this model (data not shown). This indicated that gardiquimod and imiquimod may also directly affect tumor growth and that gardiquimod and imiquimod could enhance DC activity as observed in vitro (Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Combination therapy with gardiquimod or imiquimod and DC vaccine inhibits the growth of subcutaneous B16 melanomas. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5×104 B16 cells. On day 7, mice received an intravenous infusion of 4×104 DCs, and on days 8 and 10, mice received 1 mg/kg of either gardiquimod or imiquimod by peritumoral injection. Control mice were injected with an equivalent volume of PBS. (a) The tumor volumes were calculated and the growth curves of melanomas in treated mice were determined. (b) The treated mice were killed on day 13, and tumors were weighed. Images show representative subcutaneous tumors from each group, and the mean tumor weights are depicted to the right of the images. (c) The tumor tissues were analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The black arrows indicate lymphocyte infiltration, and the yellow arrows indicate necrosis in tumor tissues. Magnification: ×200. Data are representative of three independent experiments. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, and *P<0.05, compared to the PBS treatment group. DC, dendritic cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

The difficulties in treating cancer are largely attributed to tumor metastasis; therefore, effective inhibition of tumor metastasis is the key to cancer therapy. In this report, we demonstrated the antimetastatic effects of TLR7 agonists combined with a DC vaccine in a B16 lung metastasis model. As shown in Figure 6, combination therapy with imiquimod or gardiquimod and DC vaccine resulted in a reduced number of B16 melanoma metastatic nodules. Therapy with gardiquimod combined with DC vaccine exerted a more significant effect than therapy with imiquimod combined with DC vaccine. By histochemical analysis, we observed a large number of lymphocytes infiltrating the periphery of tumor nodules. Focal necrosis was observed in the center of tumor tissues in mice treated with gardiquimod in combination with DC vaccine (data not shown). The infiltrating lymphocytes were also found in mice treated with imiquimod in combination with DC vaccine or with DC vaccine alone. These results suggest that both agonists can suppress the pulmonary metastasis of B16 melanoma.

Figure 6.

Combination therapy with gardiquimod or imiquimod and DC vaccine inhibits the pulmonary metastasis of B16 melanoma. C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with 1×106 B16 cells. On day 7, mice were injected intravenously with 4×104 DCs and 1 mg/kg of either gardiquimod or imiquimod. Control mice were injected with an equivalent volume of PBS. The mice were killed on day 14, the lungs were separated and the tumor nodules were counted. Images show representative lung metastases from each group. The mean numbers of macroscopically visible melanoma metastases are depicted to the right of the images. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, compared to the PBS treatment group. DC, dendritic cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Discussion

The importance of TLRs in innate and adaptive immunity is now well established. TLR ligands represent promising immunostimulators or vaccine adjuvants for cancer treatment. Several synthetic compounds, such as imidazoquinoline molecules, and natural nucleoside structures have been characterized as TLR7 and/or TLR8 ligands.13 After being recognized by TLR7 or TLR8, these ligands activate intracellular signaling pathways leading to the induction of type I IFNs, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines.5, 13 The major benefit of TLR7/8 agonists is that they not only activate antigen-presenting cells,14, 15, 16 but also promote activation of T and NK cells and inhibit regulatory T cell function.13, 17, 18, 19, 20 Moreover, TLR7/8 ligands have been shown to directly affect some tumor cells by inducing apoptosis and sensitizing tumor cells to killing mediated by CTLs and chemotherapeutic agents.21, 22 However, these effects depend on the kinds of TLR7/8 agonists used and the type of tumor being treated.

Imiquimod has been successfully used for the treatment of certain skin tumors, but the exact mechanisms by which it mediates its antitumor effects are not yet understood. The efficacy of gardiquimod (a new TLR7/8 agonist) in the treatment of tumors has not been demonstrated. In this study, we demonstrated that imiquimod and gardiquimod promoted the proliferation of murine splenocytes; stimulated the activation of splenic T, NK and NKT cells; increased the cytolytic ability of splenocytes against B16 and MCA-38 cell lines; and enhanced the expression of costimulatory molecules and production of IL-12 by macrophages and bone marrow-derived DCs. These results are in accordance with previous studies of other TLR7 agonists or single-stranded RNA.23 Furthermore, we found that gardiquimod exerted more potent antitumor effects than imiquimod. These results suggest that gardiquimod and imiquimod not only promote activation of antigen-presenting cells, which express high levels of TLR7/8, and therefore augment the adaptive immune response, but also might directly affect T, NK and NKT cells; in particular, these agonists may increase the cytotoxicity of NK cells. Other researchers also reported that TLR7 and/or TLR8 was expressed on T cells and NK cells19, 24 and found that imiquimod treatment increased T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ.17, 18 The TLR7/8 agonist R848 was reported to activate NK cells directly and to promote IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity in an accessory cell-dependent manner.19 Although other TLR ligands can induce activation of immune cells and promote antitumor activity, they usually function by activating antigen-presenting cells and cannot directly activate other immune effector cells. We have found that the TLR3 ligand poly I:C can activate NK cells but cannot activate T cells directly, while the TLR4 ligand LPS can activate B cells but cannot activate T and NK cells directly (data not shown). The ability to activate both innate and adaptive immune cells and to inhibit regulatory T cell function makes TLR7 agonists attractive candidates for use as immunostimulators or vaccine adjuvants.

Using an in vivo model, we further confirmed that combination therapy with gardiquimod or imiquimod and a bone marrow-derived DC vaccine inhibited and delayed the growth of s.c. B16 melanoma and suppressed pulmonary metastasis. Observed in vitro, the effect of gardiquimod was more potent. We propose that gardiquimod and imiquimod play major roles in promoting the activation of APCs and subsequently enhancing the T-cell antitumor response. Furthermore, both gardiquimod and imiquimod can stimulate the activation of T, NK or NKT cells directly or through cytokines secreted by DCs. Importantly, treatment with gardiquimod or imiquimod augmented the cytolytic capacity and cytotoxic effector molecule expression of NK cells. In addition, these TLR7/8 ligands may directly affect tumor cells by inducing tumor cell apoptosis. Further study is needed to determine the exact mechanisms by which gardiquimod and imiquimod enhance DC-based immunotherapy.

Imiquimod and other TLR7 agonists have been applied topically and orally for the treatment of certain skin tumors and some viral infections. In pharmacokinetic studies no systemic side effects were observed following topical administration of imiquimod or other TLR7 agonists because less than 1% of the topically applied imiquimod (5% cream) was absorbed into the body.25 In addition, topical TLR7 agonist treatment has not been shown to induce production of antibodies against self-antigens or development of systemic autoimmune diseases.13 Systemic administration of TLR7 agonists requires higher dosages, which might result in some toxicity; specifically, higher doses of TLR7 agonists may result in influenza-like symptoms similar to those observed with IFN-α treatment. It is important to limit the dosage of TLR7 agonists in order to evoke local activation of the immune system without systemic cytokine induction. In this study, we observed the effect of differential doses of gardiquimod and imiquimod in normal mice, and 1 mg/kg was determined to be a biologically active dose. This dosage has been proven safe and effective for antitumor therapy as reported by Dumitru.26 In an s.c. tumor model, we treated mice with TLR7 agonists by peritumoral injection, and in a lung metastatic model, we used TLR7 agonists as vaccine adjuvants by vaccinating mice with DCs and TLR7 ligands simultaneously. These delivery pathways and combination therapies might enhance the efficacy of immune responses while minimizing the side effects of TLR7 ligands.

In summary, because of their ability to activate various immune cells simultaneously, TLR7/8 agonists—especially gardiquimod—may serve as potent innate and adaptive immune response modifiers in tumor therapy. More importantly, they can be used as vaccine adjuvants to potentiate the efficiency of DC-based immunotherapy against tumors. The combination of TLR7/8 agonists with other factors, such as agonists of TLR3 or costimulatory factors, might further increase their ability to enhance antitumor immune responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 90713033), the National 973 Basic Research Program of China (no. 2007CB815800) and the National 115 Key Project for HBV Research (no. 2008ZX10002-008).

References

- Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu S, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. J Mol Med. 2006;84:712–725. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by innate receptors. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein F, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via Toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, Karow M, Adams NC, Gale NW, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5598–5603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;12:4783–4801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel J, Tormo D, Tüting T. Toll-like receptor-agonists in the treatment of skin cancer: history, current developments and future prospects. Hand Exp Pharmacol. 2008;183:201–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaisho T, Akira S. Regulation of dendritic cell function through Toll-like receptors. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:373–385. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Iwasaki A. Induction of antiviral immunity requires Toll-like receptor signaling in both stromal and dendritic cell compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16274–16279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406268101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner KR, Tyring SK, Trofatter KF, Jr, Douglas JM, Jr, Spruance S, Owens ML, et al. Imiquimod, a patient-applied immune-response modifier for treatment of external genital warts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:789–794. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft N, Bruhn KW, Nguyen BD, Prins R, Lin JW, Liau LM, et al. The TLR7 agonist imiquimod enhances the anti–melanoma effects of a recombinant Listeria monocytogenes vaccine. J Immunol. 2005;175:1983–1990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits EL, Ponsaerts P, Berneman ZN, van Tendeloo VF. The use of TLR7 and TLR8 ligands for the enhancement of cancer immunotherapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:859–875. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins RM, Craft N, Bruhn KW, Khan-Farooqi HK, Koya RC, Stripecke R, et al. The TLR-7 agonist, imiquimod, enhances dendritic cell survival and promotes tumor antigen-specific T cell priming: relation to central nervous system antitumor immunity. J Immnol. 2006;176:157–163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary G, Bangert C, Tauber M, Strohal R, Kopp T, Stingl G. Tumoricidal activity of TLR7/8-activated inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1441–1451. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larangé A, Antonios D, Pallardy M, Kerdine-Römer S. TLR7 and TLR8 agonists trigger different signaling pathways for human dendritic cell maturation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:673–683. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0808504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron G, Duluc D, Frémaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H, et al. Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R-848 up-regulate proliferation and IFN-gamma production by memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1551–1557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SJ, Hijnen D, Murphy GF, Kupper TS, Calarese AW, Mollet IG, et al. Imiquimod enhances IFN-gamma production and effector function of T cells infiltrating human squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2676–2685. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart OM, Athie-Morales V, O'Connor GM, Gardiner CM. TLR7/8-mediated activation of human NK cell results in accessory cell-dependent IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 2005;175:1636–1642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G, Guo Z, Kiniwa Y, Voo KS, Peng W, Fu T, et al. Toll-like receptor 8-mediated reversal of CD4+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2005;309:1380–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1113401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schön M, Bong AB, Drewniok C, Herz J, Geilen CC, Reifenberger J, et al. Tumor-selective induction of apoptosis and the small-molecule immune response modifier imiquimod. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1138–1149. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schön MP, Wienrich BG, Drewniok C, Bong AB, Eberle J, Geilen CC, et al. Death receptor-independent apoptosis in malignant melanoma induced by the small-molecule immune response modifier imiquimod. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1266–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Esteban V, Abdul M, Charron D, Haziot A, Mooney N. Dendritic cells differentiated in the presence of a single-stranded viral RNA sequence conserved their ability to activate CD4 T lymphocytes but lose their capacity for Th1 polarization. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:954–962. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00428-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdörfer B, Giese T, et al. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomai MA, Miller RL, Lipson KE, Kieper WC, Zarraga IE, Vasilakos JP. Resiquimod and other immune response modifiers as vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:835–847. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitru CD, Antonysamy MA, Gorski KS, Johnson DD, Reddy LG, Lutterman JL, et al. NK1.1+ cells mediate the antitumor effects of a dual Toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist in the disseminated B16-F10 melanoma model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:575–587. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0581-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]