Abstract

Aim:

To investigate the protective effect and underlying mechanisms of Bu-7, a flavonoid isolated from the leaves of Clausena lansium, against rotenone-induced injury in PC12 cells.

Methods:

The cell viability was evaluated using MTT assay. The cell apoptosis rate was analyzed using flow cytometry. JC-1 staining was used to detect the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Western blotting analysis was used to determine the phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38), tumor protein 53 (p53), Bcl-2–associated X protein (Bax), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), and caspase 3.

Results:

Treatment of PC12 cells with rotenone (1–20 μmol/L) significantly reduced the cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner. Pretreatment with Bu-7 (0.1 and 10 μmol/L) prevented PC12 cells from rotenone injury, whereas Bu-7 (1 μmol/L) had no significant effect. Pretreatment with Bu-7 (0.1 and 10 μmol/L) decreased rotenone-induced apoptosis, attenuated rotenone-induced mitochondrial potential reduction and suppressed rotenone-induced protein phosphorylation and expression, whereas Bu-7 (1 μmol/L) did not cause similar effects. Bu-7 showed inverted bell-shaped dose-response relationship in all the effects.

Conclusion:

Bu-7 protects PC12 cells against rotenone injury, which may be attributed to MAP kinase cascade (JNK and p38) signaling pathway. Thus, Bu-7 may be a potential bioactive compound for the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

Keywords: Bu-7, Clausena lansium, neuroprotection, Parkinson's disease, rotenone, apoptosis, PC12 cells

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a major age-related neurodegenerative disorder which is accompanied primarily by motor symptoms, such as resting tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia. It is pathologically characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and the accumulation of aggregated alpha-synuclein in brain stem, spinal cord, and cortex1. Several lines of evidence have converged to suggest that environmental neurotoxins, such as rotenone2, and mutant proteins, such as DJ-1, PINK1, and LRRK23, may be importantly involved in the etiopathogenesis of PD.

Long-term, systemic administration of rotenone, a natural substance which is widely used as a pesticide, produces the selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and PD-like locomotor symptoms in rats2. Among the various animal models of PD, the rotenone model has its own advantages. Firstly, unlike the other models, it reproduces most of the movement disorder symptoms and the histopathological features of PD, including Lewy bodies4, 5. Secondly, rotenone is a powerful inhibitor of complex I in the mitochondrial respiration, and recent epidemiological studies suggest the involvement of these toxic compounds in the higher incidence of sporadic Parkinsonism6, 7, 8. Observations have shown that a defect in mitochondrial complex I activity may induce the apoptosis of dopaminergic cells, which may contribute to the neurodegenerative process in PD9. Administration of rotenone has been used extensively to create PD models to screen for neuroprotective agents both in vivo10, 11 and in vitro12, 13.

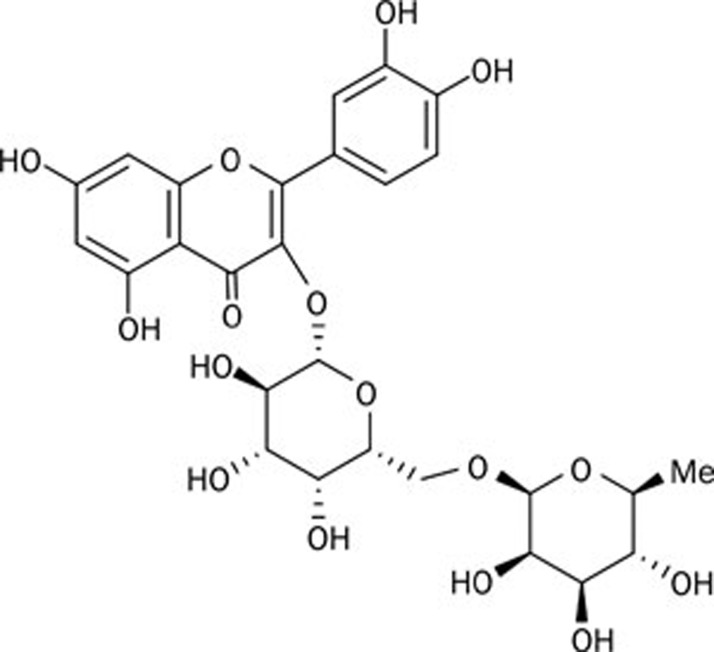

Therapeutic efforts aimed at providing protection against apoptosis may be beneficial in PD. In this regard, natural products are attractive sources of chemical structures that could exhibit potent biological activities. Clausena lansium is a fruit tree native to the south of China, and a decoction of its dried leaves was used to treat acute and chronic viral hepatitis in local folk medicine14. More recently, there has been renewed interest in the neuroprotective potential of the leaf extracts of Clausena lansium; for example, research has been carried out on the effects of clausenamide in enhancing learning and memory15, 16. In a previous attempt to detect more information about the biological activities of Clausena lansium, we separated the natural chemicals systematically from the leaves17. After preliminary screening, we found that one compound, termed Bu-7, was a biologically active substance. This is a known compound18, and the chemical structure of Bu-7 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of Bu-7.

PC12 cells, a cell line established from a rat pheochromocytoma, have many properties in common with primary sympathetic neurons and chromaffin cell cultures, and these cells have been used primarily as neuron models19. In this article, we report the protective effect of Bu-7 in PC12 cells against rotenone injury.

Materials and methods

Drugs and reagents

Bu-7 was provided by the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China). Rotenone, 6-OHDA and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (USA). JC-1 and Rhodamine 123 were purchased from Beyotime (China). Primary antibodies and secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and commercially available.

Compound preparation

The Bu-7 compound was prepared as previously described17. Briefly, the air-dried leaves (0.8 kg) of Clausena lansium were extracted with 70% ethanol for 2 h under reflux conditions, and the 70% ethanol extract was concentrated under reduced pressure. Subsequently, it was partitioned with petroleum ether (60–90 °C), ethyl acetate and butyl alcohol, respectively. The butyl alcohol portion (50 g) was chromatographed over a silica gel column using ethyl acetate-methanol as the gradient eluent (50:1–1:1, v/v) to produce 32 fractions. Fractions 20–27 were subjected to RP-18 column chromatography and eluted using a gradient of methanol-H2O (30%–70%, v/v) to 20 fractions. Fraction 11 (1.1 g) was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel and eluted with CHCl3-methanol-H2O (8:2.5:0.3, v/v/v) to yield several fractions. Fractions 6–8 (502 mg) were again subjected to RP-18 column chromatography and eluted using a gradient of methanol-H2O (20%–50%, v/v) to yield fractions A and B. Fraction A was subjected to a Sephadex LH-20 column using 70% methanol-H2O and purified using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (YMC-Pack ODS-A column [20 mm×250 mm, 5 μm]) with 13% acetonitrile-H2O (0.05% TFA) to yield Bu-7 (17 mg).

Cell culture

PC12 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Gibco, USA) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Gibco, USA), 5% equine serum (Thermo Scientific, Hyclone, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The media were changed every two or three days.

Drug treatments

Rotenone and Bu-7 were reconstituted fresh in dimethyl sulfoxide and distilled water, respectively, prior to each experiment. Bu-7 (0.1, 1, 10 μmol/L) was added 0.5 h prior to the rotenone treatment in the cell cultures to evaluate its protective effect.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. After incubation with MTT solution for 4 h, the cells were exposed to an MTT-formazan dissolving solution for 8–12 h. The optical density (OD) was then determined using an absorbance microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Toronto, Canada) at a wavelength of 570 nm. The cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the OD value of the control cultures.

Analysis of apoptosis by flow cytometry

The apoptosis rate was measured by flow cytometry, as reported previously20. Briefly, PC12 cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4), fixed in cold 70% (v/v) ethanol, and incubated at -20 °C for at least 2 h. The fixed cells were harvested by centrifugation at 250×g for 5 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in PBS at room temperature for 10 min, and after another centrifugation, the cell pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 0.2 g/L RNase A and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were then stained with propidium iodide (PI) at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL at 4 °C for 30 min. The suspensions were analyzed using a FACS scan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Changes in the inner MMP were determined by incubating with 10 μg/mL of Rhodamine 123 for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. The cells were then washed with PBS three times, and the fluorescence intensity was determined using flow cytometry. JC-1 was also used to measure the change of the inner MMP. PC12 cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL JC-1 at 37 °C. JC-1 accumulates in the mitochondria, forming red fluorescent aggregates at high membrane potentials; at a low membrane potential, JC-1 exists mainly in the green fluorescent, monomeric form. After incubating for 20 min, the cells were washed with PBS for 3 times and submitted to fluorescence microscopy analysis. The JC-1-loaded cells were excited at 488 nm, and the emission was detected at 590 nm (JC-1 aggregates) and 525 nm (JC-1 monomers). Mitochondrial depolarization was indicated by an increase in the green/red fluorescence intensity ratio, which was calculated with Image J software.

Western blot analysis

After treatment, the cells were washed with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mmol/L PMSF, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 20 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 1 mmol/L DTT, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 50 mmol/L NaF, and 20 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate Na2, pH 8.0). The protein concentrations were measured with a BCA kit (Pierce). The cell lysates were solubilized in SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA and incubated with the primary antibody, anti-JNK/p-JNK MAPK, anti-p38/p-p38 MAPK, anti-p53, anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-2, or anti-caspase 3, followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. The proteins were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence plus detection system (Molecular Device, Lmax) and analyzed with Science Lab 2005 Image Gauge software. β-Actin served as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

All of the data obtained in the experiments were represented as the mean±standard deviation (SD). The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 13.0 software package. Differences were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and P values of less than 0.05 and 0.01 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Bu-7 protects against rotenone-induced PC12 cell death

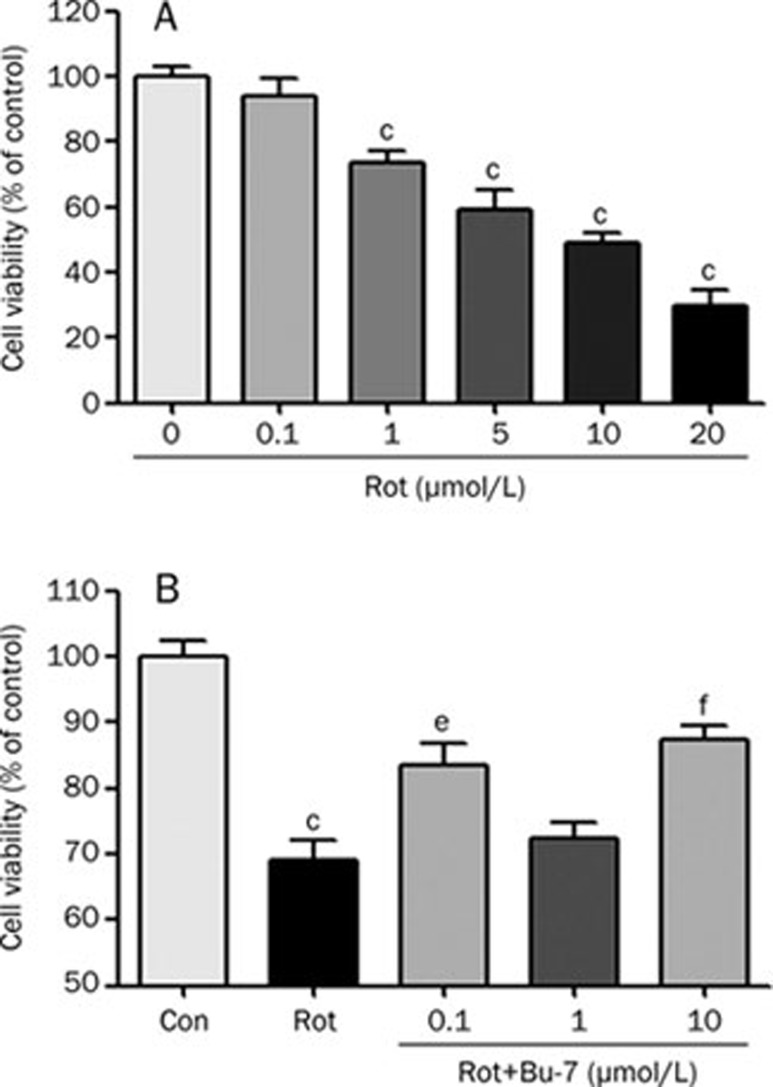

To investigate how rotenone influences neuronal cytotoxicity, PC12 cells were treated with various concentrations of rotenone (0, 0.1, 1, 5, 10, or 20 μmol/L) for 24 h. As shown in Figure 2A, rotenone induced a dose-dependent cytotoxicity in the PC12 cells. The cells were then treated for 24 h with various concentrations of Bu-7 with or without rotenone (1 μmol/L) to determine the effect of Bu-7 on the rotenone-induced cytotoxicity. The cells treated with rotenone demonstrated a viability of 69.2%±3.0%. We found that Bu-7 had a dose-dependent effect on cell viability after the rotenone treatment (Figure 2B), increasing the viability of the PC12 cells to 83.6%±3.2%, 72.3%±2.4%, and 87.3%±2.3% at a concentration of 0.1, 1 and 10 μmol/L, respectively, compared with the control group.

Figure 2.

Bu-7 reduces rotenone (Rot)-induced cell death. (A) PC12 cells were treated with various concentrations of Rot for 24 h. (B) The effect of Bu-7 was examined on PC12 cells treated with 1 μmol/L Rot for 24 h. PC12 cells were exposed to different concentrations (0.1, 1, and 10 μmol/L) of Bu-7 and Rot. The cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay. n=6. Mean±SD. cP<0.01 vs control. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 vs Rot-treated group.

Bu-7 protects against rotenone-induced apoptosis

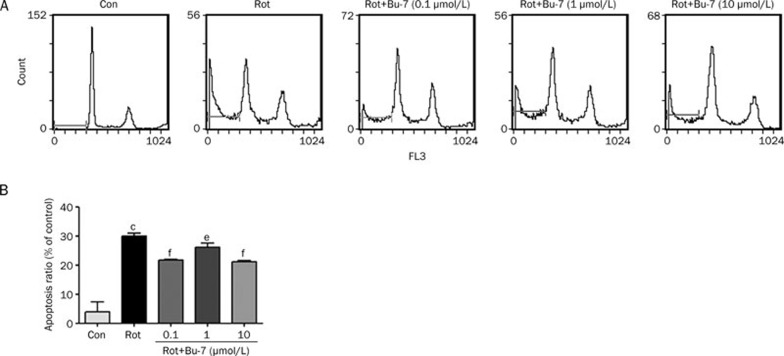

To determine how Bu-7 protects cells against rotenone, the PC12 cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and then analyzed using flow cytometry. The PC12 cells treated with rotenone (1 μmol/L, 24 h) showed an obvious apoptosis rate of 30.0%±1.0%, whereas Bu-7 treatment of the cells (0.1, 1, and 10 μmol/L) significantly attenuated rotenone-induced apoptosis (21.6%±0.2%, 26.2%±1.4%, and 21.2%±0.4%, respectively, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of Bu-7 on Rot-induced apoptosis/necrosis staining with PI analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Rot (1 μmol/L) induced the increase of apoptosis/necrosis of PC12 cells for 24 h incubation. However, this trend was inhibited by Bu-7. (B) Quantitative analysis of the ratio of apoptosis/necrosis. Mean±SD. cP<0.01 vs control. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 vs Rot-treated group.

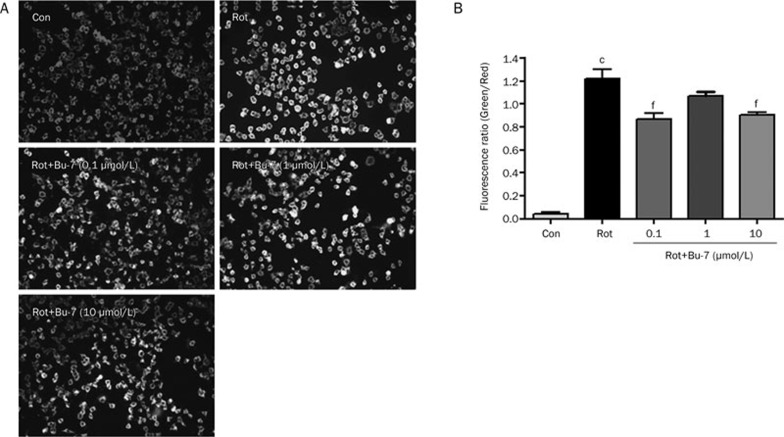

Bu-7 attenuated the rotenone-induced mitochondrial potential reduction in PC12 cells

Normal PC12 cells stained with the JC-1 dye emitted a mitochondrial orange-red fluorescence with a small amount of green fluorescence. These JC-1 aggregates within the normal mitochondria were dispersed to the monomeric form (green fluorescence) after the addition of 1 μmol/L rotenone in the culture medium for 24 h (122.1%±8.2%). However, Bu-7 relieved the rotenone-induced mitochondrial depolarization, as shown by the fluorescent color changes from green to orange-red (87.1%±5.3%, 107.0%±4.7%, and 90.2%±2.6%, respectively, Figure 4). These data showed that rotenone induced mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and caused collapse of the MMP in PC12 cells, whereas Bu-7 significantly attenuated this response.

Figure 4.

Bu-7 protected MMP of PC12 cells injured by Rot (1 μmol/L). (A) Bu-7 prevented the decrease of MMP by JC-1 staining. (B) Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence ratio of green/red. cP<0.01 vs control, fP<0.01 vs Rot-treated group.

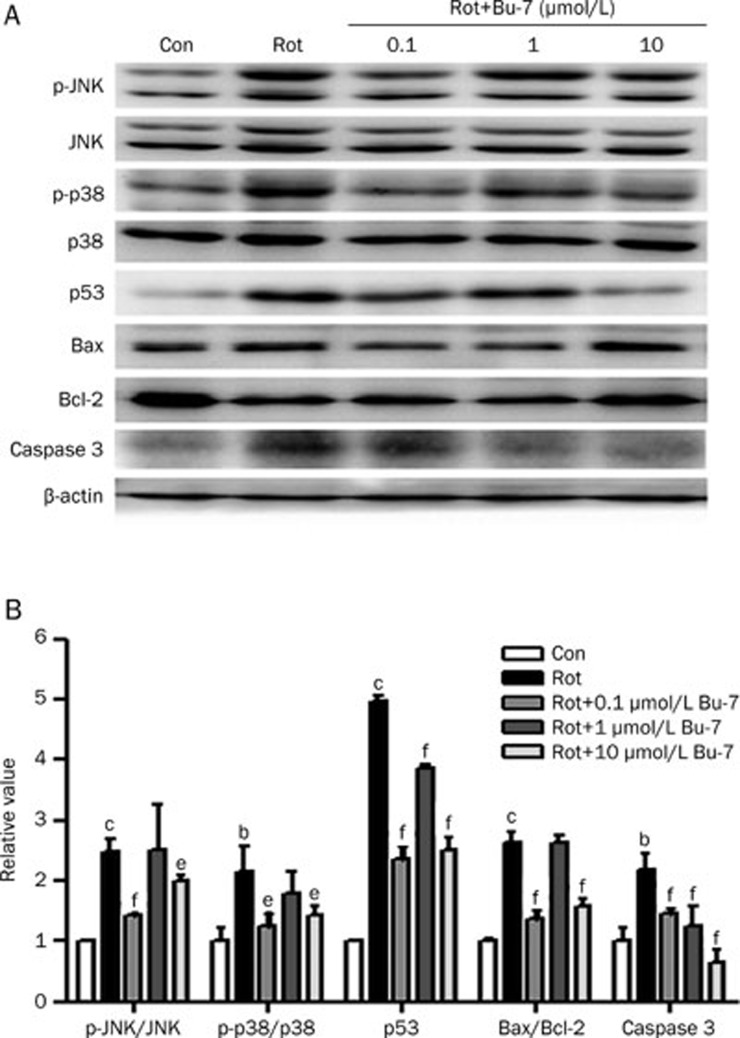

Bu-7 suppresses the levels of apoptotic proteins associated with p53 in rotenone injured PC12 cells, which is partly through the MAPK signaling pathway

The MAPK signaling pathway may be involved in the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. The effect of Bu-7 on the expression levels of apoptotic proteins was determined using western blot analysis in PC12 cells exposed to rotenone. The rotenone treatment (1 μmol/L, 24 h) increased the phosphorylation status of JNK (218.0%±11.1%) and p38 (215.6%±42.0%), increased the expression of p53 (496.1%±10.0%) and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 (264.2%±16.1%), and increased the expression levels of cleaved (presumably active) caspase 3 (219.1%±25.0%). The pretreatment with Bu-7 (0.1, 1, or 10 μmol/L) prevented the rotenone-induced increase of the above proteins in the same dose-dependent manner as was observed in the cell viability and apoptosis experiments (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of Bu-7 on the phosphorylation of JNK/p38 MAPK, the expression of p53, Bax, Bcl-2, and caspase 3 in PC12 cells exposed to Rot. (A) PC12 cells were lysed after treatment with Bu-7 and Rot (1 μmol/L). Protein expressions were detected by Western blotting. (B) Quantitative analysis of the phosphorylation of JNK/p38 MAPK, the expression of p53, Bax, Bcl-2, and caspase 3 by Science Lab 2005 Image Gauge software.n=3. Mean±SD. bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs control. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 vs Rot-treated group.

Discussion

In our previous study, we found that Bu-7 increased the cell viability of PC12 cells injured by rotenone, 6-OHDA, and MPP+ by MTT assay (unpublished observations). It is well known that rotenone, 6-OHDA and MPP+ cause neurotoxicity in cells in vitro21, 22; thus, our previous data suggested that Bu-7 may have a positive effect on anti-apoptosis and mitochondrial protection. Therefore, in our present study, we utilized rotenone to create an in vitro cell model to study the protective effects of Bu-7 in PC12 cells and tried to find the possible underlying mechanisms.

Mitochondria are involved in cell survival and play a central role in apoptotic cell death signaling through the control of cellular energy metabolism, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the release of apoptotic factors into the cytosol. Evidence showed that ROS are involved in the apoptotic mechanism of rotenone-mediated neurotoxicity23. The mitochondrial membrane permeability transition induces the formation of ROS by the inhibition of the respiratory chain and vice versa24. Our data showed that Bu-7 protected PC12 cell viability, decreased the apoptosis rate and attenuated the collapse of the MMP induced by rotenone in a manner that resembled an inverted bell-shaped curve. The results demonstrated that Bu-7 had a protective effect against rotenone injury in PC12 cells.

We then further investigated the protective mechanisms of Bu-7 against rotenone-induced apoptosis. Previous evidence from both postmortem PD brain tissues and cellular and animal models suggested that pathways involving p53/Bcl-2-family members may represent suitable targets in apoptosis in PD25, 26, 27, 28, 29. The activation of JNK and p38 were reported to be responsible for p53-dependent apoptosis including the inhibition of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, which further promoted the caspase process, which had a general role in rotenone-induced apoptosis in neuronal cells30. It was observed in SH-SY5Y cells that rotenone induced apoptosis through the activation of the JNK and p38 signaling pathways, which indicated their role in neuronal apoptosis31, 32, 33, 34. Our results showed that rotenone (1 μmol/L) induced the phosphorylation of JNK and p38 after treatment for 24 h. Bu-7 pretreatment inhibited the rotenone-induced phosphorylation of both JNK and p38 and decreased the p53 level that was increased by rotenone. Bu-7 also prevented the increase of the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and the increase of caspase 3 activity in the rotenone-treated PC12 cells. These results indicated that Bu-7 prevented the rotenone-induced apoptosis that is associated with the p53 pathway, which might occur through the inhibition of JNK and p38 activities.

Our experiments showed that the dose-response relationship of Bu-7 resembled an inverted bell-shaped curve. This kind of dose-response relationship has been reported previously21, 35, 36. It is common that a chemical binds to two or more targets/receptors with different affinities. At different doses, the compound may activate different receptors and produce different effects, even opposite ones, in which case, the dose-response relationship is irregular. Further research is required to identify the receptors in an effort to explain the inverted bell-shaped dose-response relationship for Bu-7.

In conclusion, we isolated Bu-7 from extracts of Clausena lansium leaves17 and our present observations identified a beneficial role of Bu-7 against rotenone-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells that may operate via an inhibition of the p38/JNK pathway. Epidemiological studies revealed a correlation between general pesticide (ie, rotenone) exposure and an increased risk of PD; therefore, our findings suggested that Bu-7 could be used as a leading compound that might be useful for the treatment of PD. Because our research demonstrated the utility of the bioactive substances in Clausena lansium, we are systematically extracting and separating additional compounds from Clausena lansium leaves to find out chemicals which have higher bioactivities than Bu-7; at the same time, we are attempting to chemically modify Bu-7 to obtain an increased bioactivity.

Author contribution

Bo-yu LI designed the study, performed the research, and wrote the paper; Yu-he YUAN and Jin-feng HU provided assistance in experimental methods; Dong-ming ZHANG and Qing ZHAO extracted Bu-7; and Nai-hong CHEN designed the research and revised the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 30973887, 81073078, 81073130, Key Program No U832008 and 90713045), National Sci-Tech Major Special Item for New Drug Development (No 2008ZX09101, 2009ZX09303, 2009ZX09303-003, and 2009ZX09301-003-11-1) and Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (No 20070023037).

References

- Forno LS. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:259–72. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1301–6. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Sherer TB, Greenamyre JT. Animal models of Parkinson's disease. Bioessays. 2002;24:308–18. doi: 10.1002/bies.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN. Neurotoxicant-induced animal models of Parkinson's disease: understanding the role of rotenone, maneb and paraquat in neurodegeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:225–41. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0937-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarshi A, Khuder SA, Schaub EA, Priyadarshi SS. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: a metaanalysis. Environ Res. 2001;86:122–7. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacore N, Nappo A, Gentile M, Brustolin A, Palange S, Liberati A, et al. Evaluation of risk of Parkinson's disease in a cohort of licensed pesticide users. Neurol Sci. 2002;23:S119–20. doi: 10.1007/s100720200098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Williams GR, Hollunger G. Inhibition of electron and energy transfer in mitochondria. I. Effects of Amytal, thiopental, rotenone, progesterone, and methylene glycol. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:418–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley A, Stone JM, Heron C, Cooper JM, Schapira AH. Complex I inhibitors induce dose-dependent apoptosis in PC12 cells: relevance to Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1987–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapias V, Cannon JR, Greenamyre JT. Melatonin treatment potentiates neurodegeneration in a rat rotenone Parkinson's disease model. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:420–7. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti B, Gatta V, Piretti F, Raffaelli SS, Virgili M, Contestabile A. Valproic acid is neuroprotective in the rotenone rat model of Parkinson's disease: involvement of alpha-synuclein. Neurotox Res. 2010;17:130–41. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde G De Andrade D, Madureira de Oliveria D, Barreto G, Bertolino LA, Saraceno E, Capani F, et al. Effects of the extract of Anemopaegma mirandum (Catuaba) on Rotenone-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastomas SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res. 2008;1198:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Park HJ, Park HK, Chung JH. Tranexamic acid protects against rotenone-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicology. 2009;262:171–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GT, Li WX, Chen YY, Wei HL. Hepatoprotective action of nine constituents isolated from the leaves of Clausena lansium in mice. Drug Dev Res. 1996;39:174–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Cheng Y, Zhang JT. Protective effect of (–)clausenamide against neurotoxicity induced by okadaic acid and beta-amyloid peptide25–35. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2007;42:935–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Wang LN, Song M, Zheng XW, Hang TJ, Zhang ZX. Excretion of (–)-clausenamide in rats. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2006;41:789–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Li C, Yang J, Zhang D. Chemical constituents of Clausena lansium. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2010;35:997–1000. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20100812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzhva N, Luk'yanchikov M, Ushakov V, Sarkisov L. Flavonoids of Astragalus captiosus. Chem Nat Compd. 1986;22:729. [Google Scholar]

- Greene LA, Tischler AS. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:2424–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci MC, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZT, Cao XB, Xiong N, Wang HC, Huang JS, Sun SG, et al. Morin exerts neuroprotective actions in Parkinson disease models in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:900–6. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CM, Lin RD, Chen ST, Lin YP, Chiu WT, Lin JW, et al. Neurocytoprotective effects of the bioactive constituents of Pueraria thomsonii in 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-treated nerve growth factor (NGF)-differentiated PC12 cells. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:2147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Sagara Y, Liu Y, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of reactive oxygen species production during programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1423–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polster BM, Fiskum G. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neural cell apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1281–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:120–9. doi: 10.1038/35040009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmeier PC. Prospects for antiapoptotic drug therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:303–21. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:111–21. doi: 10.1038/nrd726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri KF, Kroemer G. Organelle-specific initiation of cell death pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E255–63. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-e255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann KC, Bonzon C, Green DR. The machinery of programmed cell death. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;92:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei W, Liou AK, Chen J. Two caspase-mediated apoptotic pathways induced by rotenone toxicity in cortical neuronal cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:520–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0653fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughlan A, Newhouse K, Namgung U, Xia Z. Chlorpyrifos induces apoptosis in rat cortical neurons that is regulated by a balance between p38 and ERK/JNK MAP kinases. Toxicol Sci. 2004;78:125–34. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse K, Hsuan SL, Chang SH, Cai B, Wang Y, Xia Z. Rotenone-induced apoptosis is mediated by p38 and JNK MAP kinases in human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicol Sci. 2004;79:137–46. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junn E, Mouradian MM. Apoptotic signaling in dopamine-induced cell death: the role of oxidative stress, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, cytochrome c and caspases. J Neurochem. 2001;78:374–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G, Huang C, Li Y, Pi YH, Wang BH. Inhibitory effects of AcSDKP on proliferation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2006;58:110–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Liu R, Zhu SY, Du GH. Acute neurovascular unit protective action of pinocembrin against permanent cerebral ischemia in rats. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2008;10:551–8. doi: 10.1080/10286020801966955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]