Abstract

Purpose

To learn what medical students derive from training in humanities, social sciences, and the arts in a narrative medicine curriculum and to explore narrative medicine’s framework as it relates to students’ professional development.

Method

On completion of required intensive, half-semester narrative medicine seminars in 2010, 130 second-year medical students at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons participated in focus group discussions of their experiences. Focus group transcriptions were submitted to close iterative reading by a team who performed a grounded-theory-guided content analysis, generating a list of codes into which statements were sorted to develop overarching themes. Provisional interpretations emerged from the close and repeated readings, suggesting a fresh conceptual understanding of how and through what avenues such education achieves its goals in clinical training.

Results

Students’ comments articulated the known features of narrative medicine—attention, representation, and affiliation—and endorsed all three as being valuable to professional identity development. They spoke of the salience of their work in narrative medicine to medicine and medical education and its dividends of critical thinking, reflection, and pleasure. Critiques constituted a small percentage of the statements in each category.

Conclusions

Students report that narrative medicine seminars support complex interior, interpersonal, perceptual, and expressive capacities. Students’ lived experiences confirm some expectations of narrative medicine curricular planners while exposing fresh effects of such work to view.

Medical educators have sought means to equip their students for the interior, imaginative, ethical, and relational aspects of clinical practice, in part to redress the relentless impersonal and technological tide of recent health care. These aspects include the capacities to reflect on clinical experience,1,2 to appreciate multiple perspectives on complex events,3 to discern ethical and societal dimensions of health events,4 to tolerate uncertainty,5 and to sustain curiosity and empathy.6 Since the mid-1970s, more and more schools propose that such pedagogic goals might be achieved through the teaching of humanities and the arts.7–9 Descriptions of many such courses have been published, including creative writing courses,4,10–16 literature seminars,17–26 and museum-based art courses.27–33 Conceptual frameworks underlying these pedagogical aims have been articulated, based on theoretical models from literary theory, aesthetic theory, ethics, professionalism, and interpersonal or psychological theories.34–42 What has lagged behind the teaching of humanities and the arts, and the development of the theory, are conceptual models of what students derive from such teaching. Although there is an emerging consensus on what humanities, creative writing, social sciences, and the arts can potentially offer to medical students, what do the students themselves take away from such educational efforts?

Background

At the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University (P&S), all students participate in training in narrative medicine (NM), a field with roots in humanities, creative writing, social sciences, the arts, and reflective clinical practice. Defined as clinical practice fortified with the narrative competence to recognize, absorb, interpret, and honor the stories of self and other, NM has grown since its introduction in 2000 to become an international focus of scholarship, education, and clinical practice.43 Reaching beyond the improvement of medical education, NM achieves practical clinical goals—for example, in genetics counseling, fetal cardiology, and chaplaincy44–46—pedagogic goals in medicine and in the humanities,47 and social goals such as health care team cohesion and effective interprofessional education.48

NM has conceptualized three foundational movements of clinical practice—attention, representation, and affiliation—that can bring patients and clinicians into authentic contact as a prelude to action.49 Each movement incorporates knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable clinicians, colleagues, and patients to develop effective partnerships of recognition and care. Attention is the state of focused concentration on a person, text, or work of art that enables perception without distraction.50–52 Representation is the conferring of linguistic or visual form onto complex formless experience so that what is undergone can be perceived, recognized, and communicated to self and others.53–55 Affiliation is the development of a shared commitment to the well-being of the patient, achieved through meaningful contact among patient, physician, colleagues, and/or self. Through the simultaneous movements of attention and representation, the participants can spiral towards affiliation, the action-inducing and potentially healing goal of any clinical practice.

At P&S, all students are required to enroll, prior to clinical rotations, in one of 10 to 12 graduate-level half-semester small-group NM seminars taught each year by professors who hold the terminal degree in their discipline. NM course offerings have included courses in literature, writing, philosophy, cinema studies, mindfulness, social justice, and museum-based art (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Narrative Medicine Seminars Offered to Second-Year Medical Students at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S), 2010

| Seminar | Core content | Major teaching process |

|---|---|---|

| Close reading/writing | ||

| The Philosophy of Death | Fictional and philosophical depictions of death | Close reading, philosophic reasoning; writing prompts to fictional reading |

| Fiction Workshop | Short published fiction; essays on form; students’ short stories | Close reading of published fiction; the creative writing workshop |

| The City of the Hospital: The Medical Student as Writer | Short published essays on medicine; students’ creative nonfiction | Writing in the classroom; the writing workshop |

| Understanding Illness in Young Adults Through First-Person Narratives of Patients and Their Caregivers | Illness narratives of young adults, written and Web based | Close reading; discussion of illness in families; writing about personal experiences with illness |

| Visual art | ||

| The Professional Eye (Metropolitan Museum of Art) | Looking at exhibited works in the Met; curator-guided tours | Close looking and talking about works; studio art components |

| The Language of Visual Experience: Telling Stories About Pictures (MoMA, Museum of Modern Art) | Looking at exhibited works in MoMA; curator-guided tours | Looking at and talking about works of art; studio art components |

| Why Works of Art Matter (The Frick Collection) | Close, slow looking of one art work per session | Conversation about chosen work; readings by artists and art historians |

| Narrative Photography: Seeing the Human Story Through the Still Image | The photographic process of composing, framing, finishing; whether photography belongs in health care | Workshopping photographic work; visits to photographic installations in the city |

| Attending to Movies: Affect and Insight | Film series with salience to illness and care; cinema theory of empathy | Films watched prior to class; writing in class in response to films |

| Social sciences/other | ||

| Social Justice and Health | Curriculum development seminar on global health; sessions with thought leaders at P&S to develop curriculum in global health | Interviews with international students; collaborative student-run seminar |

| From Spoken Word to Sick Tats: Youth, Illness, and New Media | Youth culture among chronically ill adolescents | Spoken word, visual media representations from Web/video sources; guest performers |

| How Does Emotion Impact the Body? | Mind–body relationships in health and illness | Health psychology readings; class interviews; guest speakers |

| Mindfulness Meditation | Development of mindfulness through yoga and meditation | Training in methods of meditation, relaxation; readings in salience to health care goals |

The purpose of this study is to learn whether the elements of NM, as demonstrated and taught in the NM seminars, are identified by students to make a meaningful contribution to their professional development. What of value for their development as physicians do the students find they take away from these intensive seminars? The seminars reflect the conceptual frameworks of NM itself because they were designed and directed by those who have developed the field. If students perceive that the lessons learned in these seminars are helpful in their professional development, and if they can tell us how, then we stand to learn a great deal both about the needs of medical trainees and about the ability of NM to fulfill them.

The coauthors of this paper include faculty members and students engaged in the ongoing work of Columbia’s Program in Narrative Medicine. Three of the five coauthors (N.H., R.C., E.M.) have been involved as teachers or learners in the seminar series reported on in this paper. We wish to make clear our position as developers of the concepts and practices of NM and to articulate our hope that its teaching to medical students may equip them with habits of mind with which we opened this article: reflection, curiosity, perspective taking, ethical awareness, tolerance of uncertainty, and empathy.

Method

We invited all 146 medical students in the class of 2012 to participate in focus groups to discuss the lessons learned in the NM seminars. The focus group facilitators were faculty clinicians, uninvolved in teaching the NM seminars. They had undergone several hours of formal training in focus group facilitation, taught by a PhD educator skilled in qualitative research methods (D.B.). The training placed particular emphasis on encouraging comments from each focus group participant, rather than just the more extroverted or verbally expressive students. The open-ended questions used in the groups, designed to elicit nonprompted responses and to give voice to unintended and unanticipated comment, were consensually developed by the faculty facilitators, in consultation with the authors. These questions were:

Thinking back to your Narrative Medicine seminar, what stood out for you? What do you remember?

Looking back on your seminar, what do you think it was for? What was the purpose?

Does it fit into the rest of your medical education?

What can you apply to your clinical experience? What have you already applied, or what do you hope to apply, if anything?

Focus group facilitators were trained to lead the group through the scripted questions above, encouraging open discussion and participation by all members with facilitator comments kept to a minimum.

The focus groups were convened in 2010 during the transition week before students began their clinical rotations and several months after the completion of the NM seminars. Students were assigned to 1 of 10 focus groups according to their clinical rotation groups, thus combining students from the different NM seminars to ensure that the discussion centered not on individual seminars but on general features of the NM experience. Institutional review board approval was requested, and exemption status was received.

The focus groups were audiotaped, and the tapes were transcribed verbatim by an outside transcription service. Students’ names were removed from the transcripts. All transcripts were entered into ATLAS.ti software for the purpose of data management.

Iterative close readings by three readers (N.H., R.C., E.M.) were undertaken to immerse the readers in the transcripts in order to understand the intricacies of the conversations. Following a dual analytical, grounded-theory-guided process,56 each reader independently read the transcripts repeatedly, “deconstructing” the individual transcripts to list the particular topics raised by the students themselves in response to the facilitators’ open-ended prompts.57 The readers compared their lists, slowly achieving consensus regarding the topics that emerged. To ensure that the readers’ familiarity with NM concepts did not overly skew the process, two outside researchers from two different institutions were recruited to read two transcripts apiece. They were given the provisional list of topics that the authors had identified, and specifically asked to read the transcripts with the goals of critiquing and adding new topics to our list. They were also asked to assemble the topics (incorporating both theirs and ours) into more general themes. These consultations added several important topics to the study’s ultimate list (e.g., the topics coded as “perspectives,” “pedagogy,” and “listening—including nonverbal cues,” among many others).

The readers then assembled the topics into larger or overarching common-sense categories, moving from the particulars of the actual conversations to a more general conceptual map. As the focus group questions and the ensuing conversations focused on experiences across the NM curriculum (with examples coming from each student’s individual experience), codes and themes were developed that could be applied broadly to different types of seminars. (This can be seen in the breakdown by seminar category detailed in Table 2.) The initial lists of particular topics, including the outside researchers’ suggestions and pared down to avoid duplication, became the codes used in coding each transcript, and the overarching categories became the themes in which codes were grouped (see Table 2). Finally, each NM seminar was assigned a code number so as to facilitate collection of comments on each separate seminar.

Table 2.

Themes and Codes Emerging From Qualitative Analysis of Focus Group Transcripts, From a Narrative Medicine Study With Second-Year Students, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 2010*

| Themes | Frequency of codes | Theme frequency, no. (%) of total statements† | Total theme frequencies by seminar category, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection to medicine/medical education |

|

260 (36) |

|

| Affiliation |

|

173 (24) |

|

| Pleasure |

|

165 (23) |

|

| Course mechanics |

|

145 (20) |

|

| Critical thinking |

|

132 (18) |

|

| Reflection |

|

119 (16) |

|

| Attention |

|

108 (15) |

|

| Critiques of seminars |

|

99 (14) |

|

| Representation |

|

81 (11) |

|

| Definitions |

|

69 (10) |

|

A total of 726 statements were given codes; the total number of codes applied was 2,569 (average 3.5 codes per statement). Many statements received more than one code; therefore, totals add up to more than 100%. Themes are reported in order of frequency and include several minor themes not commented on in the paper (e.g., course mechanics). Frequencies are further broken down by seminar category (close reading/writing, visual arts, or social sciences/other); however, not all statements could be clearly linked to a particular seminar, limiting the utility of these data. Nevertheless, it may be seen that, for example, visual arts-related comments constitute a larger percentage of the statements coded as “attention,” and writing/reading-linked comments made up the plurality of statements coded as “representation.”

Statements were coded for the presence of themes as well as for the presence of specific codes. Theme frequency reflects he frequency of themes and codes.

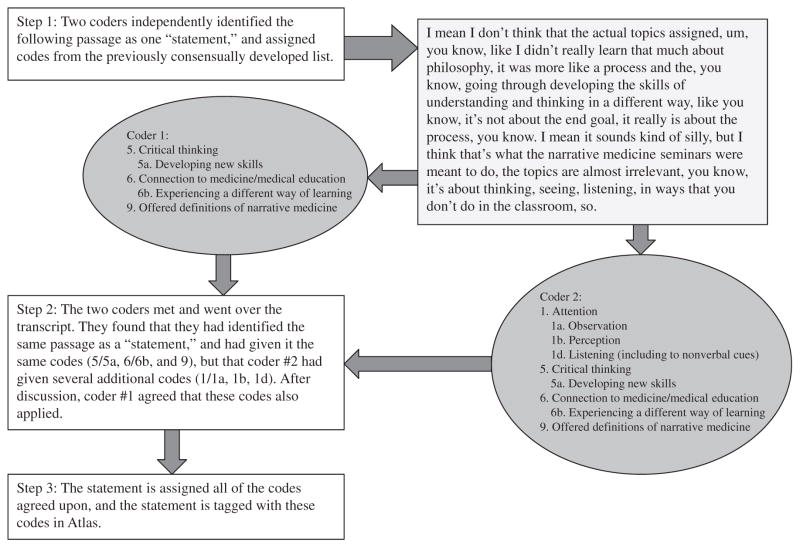

Each transcript was then coded independently by two of the three readers. Codes were assigned to statements in the transcripts; coded data were then grouped under one of the larger themes. A “statement” was defined to be a comment of any length expressing a complete thought, and typically consisted of several lines of printed transcript, but could be as short as a few words. If a student developed a thought through a brief exchange with other students, the statement was coded only once, to avoid overrepresentation by more verbally expressive students. However, if the same concept recurred in a new conversation, this was coded separately. Each pair of readers then met to resolve discrepancies in coding. Numerical counts and frequency distributions were computed for statements assigned to each code and theme. An example of this coding process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Coding student transcripts: an example. From a study of narrative medicine seminars offered to second-year medical students at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 2010.

Results

One hundred thirty students took part in the focus groups, representing 89% of the class. Our findings are reported here with examples of verbatim students’ comments from each of the major themes. Where possible, the seminar the student took is noted in italics after the quotation, along with the category (close reading/writing, visual arts, or social sciences/other).

Numerical and frequency distributions of statements among the themes and their related codes are reported in Table 2, along with a breakdown of responses by seminar category. The theme “critiques” included all critical or negative comments, constituting 14% (99/726) of the statements. These comments have been redistributed for the reporting of results into the code to which the critique is addressed.

Connection to medicine and to medical education

Students frequently recognized the clinical salience of what they had undergone in their seminar. Here, a student recognizes the limitations of medical documentation:

When you write your admission note … it’s non-fiction writing definitely, it’s just very precise, certain words you must use, certain words you would never use in that note. And then the non-fiction writing … put emphasis on different things in a way you could never do in a chart, but they’re telling the same story…. I thought that was directly applicable to what I’ll be doing for the next two years and the rest of my life. Keeping in mind that the admission note doesn’t really tell the full story. It doesn’t tell you necessarily the feeling in the room. —The City of the Hospital: The Medical Student as Writer (close reading/writing)

The connections between NM and clinical practice seemed evident to students without explicitly being stated by the instructors. Students figured out on their own what the dividends might be for their clinical practice, as in this example:

And it seems like when you’re in a hospital, you have like you know, 10 minutes or whatever per patient, but I think this made me more kind of observant…. I started to notice like smaller details that I never would have noticed before. —The Language of Visual Experience: Telling Stories About Pictures (visual arts, based at Museum of Modern Art)

Other students connected NM to medical education, pointing out the utility of experiencing a different way of learning while in the preclinical years of medical school, and identifying the seminars as a place to consider topics that can be difficult to broach in the traditional classroom setting:

I’m a veteran, and I was in The Philosophy of Death…. I talked about some things in there that I had never really talked about necessarily in a sort of classroom environment. And it was a little uncomfortable, to be honest…. Death has different meanings for some people, you know … it’s sort of a space that is not ordinarily shared, especially amongst people that you aren’t very close to. —The Philosophy of Death (close reading/writing)

The consistent connection of NM to medicine or medical education suggested a lens through which students viewed their learning. It was as if the students always wore their glasses of professional development, assessing their day-today experiences with a calculus of how these experiences contributed to “becoming a doctor.” However, some students challenged an easy connection to medicine or medical education:

It just sometimes seems very contrived to me … where we were trying to … really looking at something, like, you need to look at the patient this way. And clearly, yes, you need to look at the patient that way. But I think there was so much more you could have gotten out of it, that couldn’t be explained that way. I thought it was kind of cheapening it a little. —Why Works of Art Matter (visual arts, based at The Frick Collection)

Affiliation

Most of the comments related to affiliation focused on patients. As one student remarked:

Everybody goes and specializes in … medicine … so whenever you can go deeper into outside interests … you have less risk for marginalizing yourself … [it] just helps to relate to patients more. (Seminar not specified.)

Other comments related to affiliation to classmates or workplace colleagues.

I … feel like the most important thing is getting us to realize how to work with our classmates and talk with them and work outside of the normal classroom mentality, and realize that there are these people we can go to when … we do struggle with death and dying, it’s not us doing it alone. (Seminar not specified.)

The affiliative dividends for students were traceable to the NM methods adopted by many seminars. Typically, students in a seminar might read or view something together, write about or otherwise represent their responses, and then share those representations with classmates by reading aloud their writing, displaying their photographs, or expressing responses to a painting or sculpture. Many valued the connections within their NM group.

There are people in my group that I didn’t ever really talk to before but we all, like, shared the same choice of writing and, like, many people’s stories really, like, brought us, like closer in, like, a cool way. (Close reading/writing, seminar not specified.)

However, statements like the one below suggested that affiliation brought some students too close for comfort, with peer critiques becoming a source of stress:

I think my class was pretty stressful … every week we had to write an assignment, and hand it in, and read it aloud, and then everyone critiqued it, and like it’s cool you learn about your classmates, but … I don’t look back on it thinking like man, this really is going to help me moving forward. (Close reading/writing, seminar not specified.)

Pleasure

A substantial number of students commented on experiencing pleasure, beauty, or well-being as a direct result of the seminar, in a time when they reported feeling drained, stressed, burned out, or even turned against their choice of medicine as a profession.

For me, it was definitely the highlight of the semester. It was the only class I really enjoyed. —The Professional Eye (visual arts, based at the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

We all loved, like, waiting for Tuesday to come and [read] stories and it was just because we weren’t ever forced to do anything … medical…. It was just like being able to do something that we really loved and were passionate about…. Those experiences all ground us again. —Fiction Workshop (close reading/writing)

A few students, while acknowledging the pleasure of leaving campus, would have preferred more free time to independently explore interests outside of medicine:

[I don’t necessarily] think it should be in the medical curriculum…. I like going to museums but I’d sorta feel like it’s appropriate on your own time…. Don’t force me to be somewhere at a particular time on a particular day. —How Does Emotion Impact the Body? (social sciences/other)

Critical thinking

With some regularity, students talked about cognitive skills such as examining one’s assumptions or considering new perspectives.

I think understanding that there are different ways to tell the story helps us to understand and be aware that … all our patients are different. It may remind us not to stereotype our patients, which is hard not to do, but I think maybe we might catch ourselves doing it sometimes…. Maybe understanding narrative medicine will help us to do that. (Seminar not specified.)

A drawing exercise at an art museum led this student to appreciate the value of her classmates’ differing perspectives:

We all stood around [the work of art] and we started sketching from the original position and after a certain amount of time … you had to move to the next position [and] leave your drawing behind and … pick up the following person’s drawing and … continue drawing the sketch in on top of whatever the person was doing before. [Laughing] It was funny to see how what you’re looking at, obviously, would change from different positions. But also, the person who was there before saw something completely different from what you were seeing. And it was … very revealing. (Visual arts, museum-based, seminar not specified.)

Reflection

Students talked about personal or emotional growth when they contemplated their experiences with the seminars. Some talked about how isolated they felt from one another and from “normal” persons (those not connected to medical education) because of the relentless and flattening demands made on their time and spirit by the routines of our school.

I realized halfway through that Tuesday evening when I got home was the most human and most connected I felt all week…. I was so used to eating, sleeping, and breathing class and studying…. I dreamed that I was studying. It overtakes you and so to feel like you’re connected to art and to other people … it was so valuable … we have such a demanding life ahead of us, that we have something that forces us to take time to reconnect. (Seminar not specified.)

I feel like it’s kind of a time out where you reflect … whatever you did in narrative medicine was just so different than what we did during the second year and probably what we’ll be doing this year, it’s kind of like, I feel like you can become a little bit of a robot as a doctor, uh, and this is just like stops you and like gives you some kind of a reflection and lets you … remember that there’s a whole other world out there. (Seminar not specified.)

Attention

Students commented frequently on observation, perception, mindfulness, or listening. Each means of attention enhanced perception of persons, texts, or visual materials. One student said:

You have to be able to observe something, think about something, look at it in a certain frame and sort of take that picture and you have to compare it to that picture in three months. A really good doctor would be able to do that, and be able to see, I remember what this person looked like a month ago, and now … I see the slight changes three months from now. Maybe that’s what’s gonna separate a good doctor from a great doctor. —Narrative Photography: Seeing the Human Story through the Still Image (visual arts)

Another student achieved a new level of attention to classmates through hearing their stories:

Each week we would just read each other’s stories … just seeing these people that you’ve known for a year and a half and always studying science together and then reading like a 10-page story, seeing that there’s so much more to that person than just a scientist or a student…. —Fiction Workshop (close reading/writing)

Representation

Students commented on their new powers of representation in either visually depicting or writing about events and experiences. In particular, students found writing to be an avenue to discover their own ideas, to perceive what they otherwise might have missed, and to express out of themselves some complex thoughts and emotions:

My course [focused on] writing your thoughts … and how that can be therapeutic, in regards to the patient and also the person that is administering to the patient—especially something that might be very difficult for you to deal with, such as death of the patient … and the idea that maybe writing that out might help you to … get your thoughts and feelings out and organize what, I guess, in the end you thought about the experience. —From Spoken Word to Sick Tats: Youth, Illness and New Media (social sciences/other)

I found it useful to kind of encapsulate everything from one experience into a page or two of writing and share it with other people. (Close reading/writing, seminar not specified.)

A small number of students felt that they did not need the NM seminar experience, as they already had expertise in representation, but still recognized its value:

I was a liberal arts major, so all I took was English, theater and art classes, so it sort of felt like a redundant experience … but I understand that a lot of people haven’t had that opportunity. (Seminar not specified.)

Discussion

We readers were deeply moved and surprised by the results of this study. The students’ spontaneous conversation, complex and challenging yet generous and gentle to each other, demonstrated their ability to enter discourse with those with whom they might disagree, to appreciate other points of view, and to not feel personally threatened by other opinions—all qualities that students specifically commented on in reference to their NM seminars. Their words depicted their suffering and grit along with the dividends they gladly accepted from their seminars in literary studies, visual arts, or creative writing. These dividends, visible across the NM curriculum regardless of discipline, are consistent with much of what NM intends to provide through its pedagogy: the tools to perceive, to behold, to enter, and to represent worlds found in reality, words, or pictures so as become attentive enough to effectively deliver health care to others.

This study was undertaken to gain a detailed understanding of how the conceptual foundations of the field of NM translate (or fail to translate) into the learning needs and experiences of our medical students, who are developing their own professional identities. We found that our students did indeed speak to themes of attention, representation, and affiliation in their experiences of learning NM. The study added a layer of specificity regarding the avenues by which the narrative training led to the ultimate goal of affiliation.

Other themes emerged (critical thinking, reflection, and pleasure) that appeared conceptually to us as a syntropic triad of paths toward students’ professional development: cognitive (that we coded as “critical thinking”), interior (coded as “reflection”), and sensory (coded as “pleasure”). We locate this triad within our developing ethos of NM, informed by the ideas of a number of 20th-century thinkers. The cognitive processes the students described—perspectival, mutually constructed, outside of the self—seem related to forms of knowing described by phenomenologist Hans-Georg Gadamer54 as rooted in language’s capacity to lead one to discover what one thinks and to open oneself to the “radical negativity” of generative doubt. The category of “reflection” includes the interior work students find themselves doing, suggesting a form of self-knowing described by phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty,58 an awareness of oneself as both corporeally present in the universe and in direct and transformative contact with it. And the important and unanticipated category of “pleasure,” incorporating sensual delight at visual and literary beauty, as the foundation of a formative experience, reflects us back to the aesthetics of philosopher and educator John Dewey.59

NM has asserted that for clinicians, attention and representation spiral together in complex ways toward affiliation with patients, colleagues, or communities, the ultimate clinical goal.49 We wonder now if, for these preclinical students, attention and representation may work together through different pathways. Not yet identifying themselves as clinicians, but keenly aware that they were taking steps further away from “normal people” and toward this new professional identity, our students saw every experience through the lens of this expectation of professional development. As they attempted to make sense of and gain comfort with their new role, they employed the triad of cognitive, interior, and sensory processes, eventually reaching for the same ultimate goal of affiliation with patients and colleagues.

Our study has limitations, most notably the inevitable subjectivity of individual coders assessing spontaneous human speech, as well as the inherent bias in any internal evaluation. While we attempted to counter our bias, seeking review by independent researchers, double-coding each transcript, and reconciling differences through a process of consensus, the process of seeking evidence for one’s own stated pedagogical goals is disturbingly tautological. Our analysis did not include follow-up queries with efforts to confirm provisionally identified themes with the focus group participants (iterative data collection), making the study more grounded theory analysis of observational data than true grounded theory research.56 This was an observational qualitative study, with no control; it is possible that any effects we found were due to other aspects of the medical curriculum. We remind the reader not to draw broad conclusions from our findings. Rather, this pilot study will help guide our future investigations into the meaning of narrative work.

Despite our study’s limitations, by virtue of having sounded the depths and capacities of these seminars in our students’ experiences, we can strengthen our teaching of NM to P&S medical students with an expanded awareness of the meaning and value to students of the content and process of our pedagogy. Not only should we be eager to increase students’ capacities to read and write well and to appreciate visual art and cinema, but we should also encourage them to engage in open, mutually exposing discourse that builds rather than limits collaboration, that promotes reflection not only on medical actions but on how one lives in one’s world, and that encourages the cognitive, interior, and sensory dimensions of learning.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Regina Russell and Chris Osmond for consultation on thematic analysis.

Funding/Support: Funding for this study came in part from NIH grant 5K07HL082628. Additional support was provided by the Steve Miller Fellowship in Medical Education sponsored by the Department of Pediatrics at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Approval for this study was requested from the institutional review board of the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and exemption status was received (IRB AAAF3159).

Contributor Information

Dr. Eliza Miller, Resident, Department of Neurology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York.

Dr. Dorene Balmer, Associate professor, Department of Pediatrics, and associate director, Center for Research, Innovation and Scholarship in Medical Education, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

Ms. Nellie Hermann, Creative director, Program in Narrative Medicine, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York

Ms. Gillian Graham, Student, Yale School of Nursing, New Haven, Connecticut

Dr. Rita Charon, Professor of clinical medicine and executive director of the Program in Narrative Medicine, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York.

References

- 1.Wear D, Zarconi J, Garden R, Jones T. Reflection in/and writing: Pedagogy and practice in medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:603–609. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824d22e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien B. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller SZ, Schmidt HJ. The habit of humanism: A framework for making humanistic care a reflexive clinical skill. Acad Med. 1999;74:800–803. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roff S, Preece P. Helping medical students to find their moral compasses: Ethics teaching for second and third year undergraduates. J Med Ethics. 2004;30:487–489. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.003483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belling C. A Condition of Doubt: The Meanings of Hypochondria. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpern J. From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charon R, Williams P, editors. Special Theme Issue: The Humanities and Medical Education. Acad Med. 1995;70:758–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittrich L, editor. Special Theme Issue: Humanities Education. Acad Med. 2003;78:951–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans M, Finlay IG, editors. Medical Humanities. London, UK: BMJ Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson R, Schiedermayer D. The Art of Medicine Through the Humanities: An overview of a one-month humanities elective for fourth year students. Med Educ. 2003;37:560–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rucker L, Shapiro J. Becoming a physician: Students’ creative projects in a third-year IM clerkship. Acad Med. 2003;78:391–397. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200304000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro J, Rucker L. Can poetry make better doctors? Teaching the humanities and arts to medical students and residents at the University of California, Irvine, College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:953–957. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: Using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004;79:351–356. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson T, Lamont-Robinson C, Younie L. “Compulsory creativity”: Rationales, recipes, and results in the placement of mandatory creative endeavour in a medical undergraduate curriculum. [Accessed October 14, 2013];Med Educ Online. 2010 15 doi: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5394. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3037267/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nevalainen MK, Mantyranta T, Pitkala KH. Facing uncertainty as a medical student—a qualitative study of their reflective learning diaries and writings on specific themes during the first clinical year. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lie D, Shapiro J, Cohn F, Najm W. Reflective practice enriches clerkship students’ cross-cultural experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S119–S125. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1205-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampshire AJ, Avery AJ. What can students learn from studying medicine in literature? Med Educ. 2001;35:687–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lie D, Rucker L, Cohn F. Using literature as the framework for a new course. Acad Med. 2002;77:1170. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200211000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins AH, Ballard JO, Hufford DJ. Humanities education at Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. Acad Med. 2003;78:1001–1005. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones T, Verghese A. On becoming a humanities curriculum: The Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Acad Med. 2003;78:1010–1014. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krackov SK, Levin RI, Catanesé V, et al. Medical humanities at New York University School of Medicine: An array of rich programs in diverse settings. Acad Med. 2003;78:977–982. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery K, Chambers T, Reifler DR. Humanities education at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:958–962. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray J. Development of a medical humanities program at Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine, Nova Scotia, Canada, 1992–2003. Acad Med. 2003;78:1020–1023. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spike JP. Developing a medical humanities concentration in the medical curriculum at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York, USA. Acad Med. 2003;78:983–986. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro J. The least of these: Reading poetry to encourage reflection on the care of vulnerable patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1381–1382. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1699-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shapiro J, Duke A, Boker J, Ahearn CS. Just a spoonful of humanities makes the medicine go down: Introducing literature into a family medicine clerkship. Med Educ. 2005;39:605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardes CL, Gillers D, Herman AE. Learning to look: Developing clinical observational skills at an art museum. Med Educ. 2001;35:1157–1161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolev JC, Friedlaender LK, Braverman IM. Use of fine art to enhance visual diagnostic skills. JAMA. 2001;286:1020–1021. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reilly JM, Ring J, Duke L. Visual thinking strategies: A new role for art in medical education. Fam Med. 2005;37:250–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elder NC, Tobias B, Lucero-Criswell A, Goldenhar L. The art of observation: Impact of a family medicine and art museum partnership on student education. Fam Med. 2006;38:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro J, Rucker L, Beck J. Training the clinical eye and mind: Using the arts to develop medical students’ observational and pattern recognition skills. Med Educ. 2006;40:263–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:991–997. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0667-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klugman CM, Peel J, Beckmann-Mendez D. Art rounds: Teaching interprofessional students visual thinking strategies at one school. Acad Med. 2011;86:1266–1271. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumagai AK. Perspective: Acts of interpretation: A philosophical approach to using creative arts in medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:1138–1144. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825d0fd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter KM. Doctors’ Stories: The Narrative Structure of Medical Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trautmann J. The wonders of literature in medical education. Mobius. 1982;2:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jurecic A. Illness as Narrative. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: The health benefits of narrative. Lit Med. 2000;19:3–18. doi: 10.1353/lm.2000.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank A. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching medicine as a profession in the service of healing. Acad Med. 1997;72:941–952. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones AH. Literature and medicine: Narrative ethics. Lancet. 1997;349:1243–1246. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bishop JP. Rejecting medical humanism: Medical humanities and the metaphysics of medicine. J Med Humanit. 2008;29:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s10912-007-9048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charon R. Narrative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowaczyk MJ. Narrative medicine in clinical genetics practice. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1941–1947. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chambers S, Glickstein J. Making a case for narrative competence in the field of fetal cardiology. Lit Med. 2011;29:376–395. doi: 10.1353/lm.2011.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olson BM. Narrative medicine: Recovery of soul through storytelling of the chronically mentally ill. [Accessed October 14, 2013];Vision. 2012 :22. http://www.nacc.org/vision/Sept_Oct_2012/ru.asp.

- 47.Wooden S. Narrative medicine in the literature classroom: Ethical pedagogy and Mark Haddon’s “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time”. Lit Med. 2011;29:274–296. doi: 10.1353/lm.2011.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charon R. Commentary: Our heads touch: Telling and listening to stories of self. Acad Med. 2012;87:1154–1156. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628d6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charon R. Narrative medicine: Attention, representation, affiliation. [Accessed October 14, 2013];Narrative. 2005 13:261–270. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/narrative/summary/v013/13.3charon.html. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weil S. Waiting for God. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murdoch I. The Sovereignty of Good. London, UK: Routledge; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833–839. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loewald H. Sublimation: Inquiries Into Theoretical Psychoanalysis. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gadamer H-G. Truth and Method. 2. London, UK: Continuum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.James H. The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kennedy TJ, Lingard LA. Making sense of grounded theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of Perception. London, UK: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dewey J. Art as Experience. New York, NY: Berkley Publishing Group; 1934. [Google Scholar]