SUMMARY

The ocular motility disorder “Congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1″ (CFEOM1) results from heterozygous mutations altering the motor and 3rd coiled-coil stalk of the anterograde kinesin, KIF21A. We demonstrate that Kif21a knock-in mice harboring the most common human mutation develop CFEOM. The developing axons of the oculomotor nerve’s superior division stall in the proximal nerve; the growth cones enlarge, extend excessive filopodia, and assume random trajectories. Inferior division axons reach the orbit but branch ectopically. We establish a gain-of-function mechanism and find that human motor or stalk mutations attenuate Kif21a autoinhibition, providing in vivo evidence for mammalian kinesin autoregulation. We identify Map1b as a Kif21a interacting protein and report that Map1b−/− mice develop CFEOM. The interaction between Kif21a and Map1b is likely to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of CFEOM1, and highlights a selective vulnerability of the developing oculomotor nerve to perturbations of the axon cytoskeleton.

INTRODUCTION

A subset of the 45 human kinesin motor proteins contributes to neuronal development and maintenance through cargo transportation and/or cytoskeletal regulation, and mutations in 8 kinesins have been reported to cause neurological disorders. Among these, congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 (CFEOM1) results from a small number of recurrent and often de novo heterozygous mutations in the kinesin-4 family member, KIF21A (Yamada et al., 2003). CFEOM1 is a disorder limited to congenital blepharoptosis (ptosis or drooping eyelids) and restricted eye movements. Vertical movements are markedly limited and neither eye can be elevated above the midline, while horizontal movements vary from full to none. Aberrant residual eye movements are common, supporting errors in extraocular muscle (EOM) innervation (Engle et al., 1997; Yamada et al., 2003).

KIF21A is composed of an amino terminal motor domain, a central stalk domain, and a carboxy terminal domain containing WD40 repeats. Twelve heterozygous missense and 1 heterozygous single amino acid deletion account for all KIF21A mutations among the 106 unrelated CFEOM1 probands reported to date (Chan et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). The mutations alter 6 amino acid residues in the 3rd coiled-coil region of the stalk and 2 residues in the motor domain, and result in indistinguishable phenotypes that are limited to ptosis and ocular dysmotility (Demer et al., 2005; Yamada et al., 2003). Mapping the mutations to the Kif21a primary and the three-dimensional motor structures highlight the clustering of 11 mutations in the 3rd coiled-coil stalk domain, while 2 mutations map close to one another in loop 1 and helix α6 on the lateral surface of the highly conserved motor domain, a region of unknown function far from the kinesin motor nucleotide-binding pocket and the microtubule-binding domain (Figures 1A and S1A).

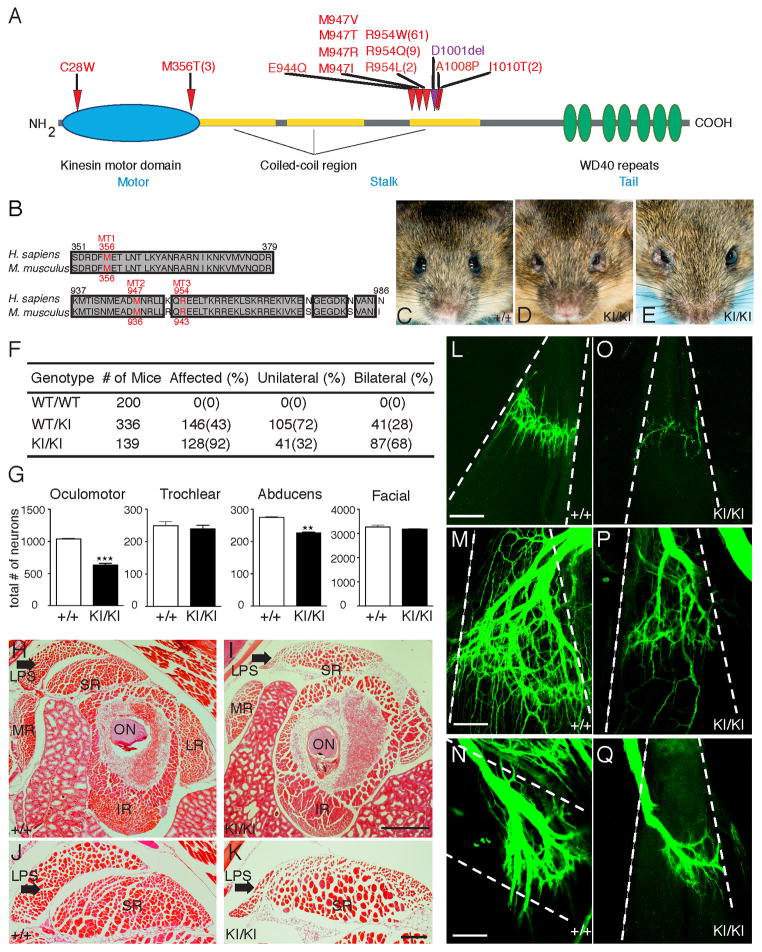

Figure 1. Kif21a R954W KI mice recapitulate human CFEOM1.

(A) Schematic of KIF21A protein highlighting amino acid substitutions (red) and single residue deletion (purple) resulting from human CFEOM1 mutations. The number of reported unrelated probands indicated within parenthesis if more than one. (B) Alignment of human and mouse KIF21A demonstrates conservation of the motor domain (MT1) and two 3rd coiled-coil stalk domain (MT2 and MT3) substitutions studied. (C) 129/S1 Kif21a+/+ mouse with normal eyes. (D, E) 129/S1 Kif21aKI/KI mice with bilateral (D) and unilateral (E) ptosis and globe retraction. (F) Penetrance of eye phenotype in adult Kif21a+/KI and Kif21aKI/KI mice. (G) Bilateral motor neuron cell counts of adult Kif21a+/+ versus Kif21aKI/KI mice: OMN 1023±31 vs. 612±54; abducens 137±6 vs. 113±5; facial 1628±75 vs. 1579±40; trochlear 249±25 vs. 239±22; n= 4,4 **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001. (H–K) H&E stained cross-sections of EOMs posterior to the globe from adult Kif21a+/+ (H, J) and Kif21aKI/KI (I, K) mice, with LPS and SR at higher magnification in J and K (n=6,6). LSP indicated by arrow. Scale bars (H, I) 200 μm, (J, K) 50 μm. (L–Q) Confocal images of isolated EOM innervation after anterograde lipophilic dye tracer studies of ocular cranial nerves in P0 Kif21a+/+ (L–N) and Kif21aKI/KI (O–Q) mice. Note decreased innervation received by LPS (L, O), SR (M, P), and LR (N, Q) in Kif21aKI/KI compared to Kif21a+/+ mice (n= 5,5). Dashed lines outline boundary of muscle bodies oriented from origin (top) to insertion (bottom). Scale bars 100 μm. Abbreviations: optic nerve (ON), levator palpebrae superioris (LPS), superior rectus (SR), lateral rectus (LR), medial rectus (MR), inferior rectus (IR).

See also Figure S1.

Kif21a is an anterograde ATP-dependent motor protein (Marszalek et al., 1999) that interacts in vitro with Kank1, a regulator of actin polymerization (Kakinuma and Kiyama, 2009). The interaction of Kif21a with the Kank1/LL5B complex at the cell cortex stabilizes microtubule dynamics in vitro (van der Vaart et al., 2013). Human and mouse KIF21A/Kif21a is expressed widely in vivo, and is present in the cell body, axons, and dendrites of most neuronal populations including cranial motor neurons, as well as in EOM and skeletal muscles, from early development into adulthood (Desai et al., 2012). The spatial expression of KIF21A does not appear altered in individuals with CFEOM1 (Desai et al., 2012). Thus, the neurobiology of CFEOM1 and how human Kif21a mutations cause this very circumscribed developmental disorder remain unclear.

In this study, we generated Kif21a knock-in and knock-out mouse models to define the CFEOM1 disease etiology, and demonstrate that CFEOM1 mutations act through a gain-of-function mechanism to attenuate Kif21a autoinhibition. We find that mutant hyperactive Kif21a causes thinning of the distal oculomotor (OMN) nerve with hypoplasia of the superior division (OMNsd) and aberrant branching of the inferior division (OMNid). Stalled proximal OMNsd axons have turning defects, with enlarged growth cones and increased numbers of filopodia. We then demonstrate that Kif21a interacts with Map1b and Map1b−/− mice have CFEOM1, supporting a critical role of their interaction in the pathogenesis of CFEOM1.

RESULTS

Kif21a R954W knock-in mice recapitulate human CFEOM1

Human KIF21A and mouse Kif21a proteins are 93% homologous, and all residues altered by CFEOM1 mutations are conserved between the two species (Figure 1B). Moreover, 74% of probands harbor the specific R954W substitution, while 89% harbor mutations that alter residue R954. Thus, to study the pathogenesis of CFEOM1, we introduced a 2,827C→T mutation into the endogenous mouse Kif21a locus, generating Kif21a knock-in mice harboring R943W (Kif21aKI), the equivalent of the human R954W substitution (Figure S1B–S1D). Kif21a+IKI and Kif21aKI/KI mice are viable, fertile, and recovered in Mendelian ratios, and two separately generated 129/S1 Kif21aKI lines were indistinguishable. Adult 129/S1 Kif21aKI mice exhibit the CFEOM1 external phenotype of unilateral or bilateral ptosis and/or globe retraction that is 92% penetrant and primarily bilateral in Kif21aKI/KI mice, 43% penetrant and primarily unilateral in Kif21a+IKI mice, and absent in Kif21a+/+ mice (Figure 1C–1E and 1F).

EOMs are innervated by the paired OMN, trochlear, and abducens cranial nerves (Figure S1E). The OMN nerve divides just prior to entering the orbit, with the larger OMNid innervating the medial rectus (MR), inferior rectus (IR), and inferior oblique (IO) muscles and the ciliary ganglion, and the smaller OMNsd innervating the superior rectus (SR) and the levator palpebrae superioris (LPS) muscles. Postmortem pathology of an adult with CFEOM1 (Engle et al., 1997) resulting from the R954W KIF21A amino acid substitution (Yamada et al., 2003) revealed hypoplasia of the SR and LPS EOMs which elevate the eye and eyelid, respectively, and absence of the OMNsd and corresponding somatic motor neurons (Figure S1E). The OMNid and the abducens nerve were also thin, and the EOMs they innervated had nonspecific changes. Similar orbital changes were documented by magnetic resonance imaging of individuals with CFEOM1 and motor or stalk mutations (Demer et al., 2005).

We asked if mature Kif21aKI/KI mice recapitulated the human CFEOM1 pathology. Bilaterally affected adult Kif21aKI/KI mice had a 38% and 12% reduction in the number of OMN and abducens motor neurons, respectively, compared to wild-type (WT) mice (Figures 1G and S1F). The LPS muscle was markedly reduced in size, with persistent attachment to the SR (Figure 1H–1K). Moreover, LPS and SR EOM innervation and, to a lesser degree, LR EOM innervation, were altered (Figure 1L–1Q). In contrast, innervation of other EOMs, ciliary ganglion, nasal sensory pad, and efferent fibers to the cochlea were largely indistinguishable between mutant and WT mice (Figure S1G–S1L). General autopsy, overall brain and brainstem size and architecture, and retinal ganglion cell axonal projections appeared unremarkable (Figure S1M–S1S). Furthermore, affected Kif21aKI/KI mice had normal behavioral visual acuity of 0.4 cycles/degree (Prusky et al., 2004). Thus, Kif21aKI/KI mice recapitulated findings observed in humans with CFEOM1 with minimal differences. Unlike outbred but similar to some inbred families (Sener et al., 2000; Yamada et al., 2004), the mice had an incompletely penetrant CFEOM1 phenotype that varied with genetic background, could appear unilateral, and generally had only mild SR muscle pathology.

Kif21aKI/KI oculomotor nerve superior branch axons terminate prematurely within a bulb

We evaluated peripheral nerve development in E11.5 Kif21aKI/KI whole mount embryos. To enhance visualization of developing motor nuclei and nerves, we crossed Kif21aKI and WT mice to IslMN:GFP transgenic mice (Lewcock et al., 2007). The exit, outgrowth, and trajectory of the OMN, as well as other cranial and spinal nerves of Kif21aKI/KI embryos could not be distinguished from WT littermates (Figures 2A–2B and S2A–S2B). This is in contrast to the TUBB3KI/KI mutant OMN nerve in a similar OMN disorder, CFEOM3, which projects aberrantly toward the superior oblique muscle that is normally innervated by the trochlear nerve (Tischfield et al., 2010). We did, however, note thinning of distal OMN nerves in Kif21aKI/KI embryos (Figures 2B and S2B).

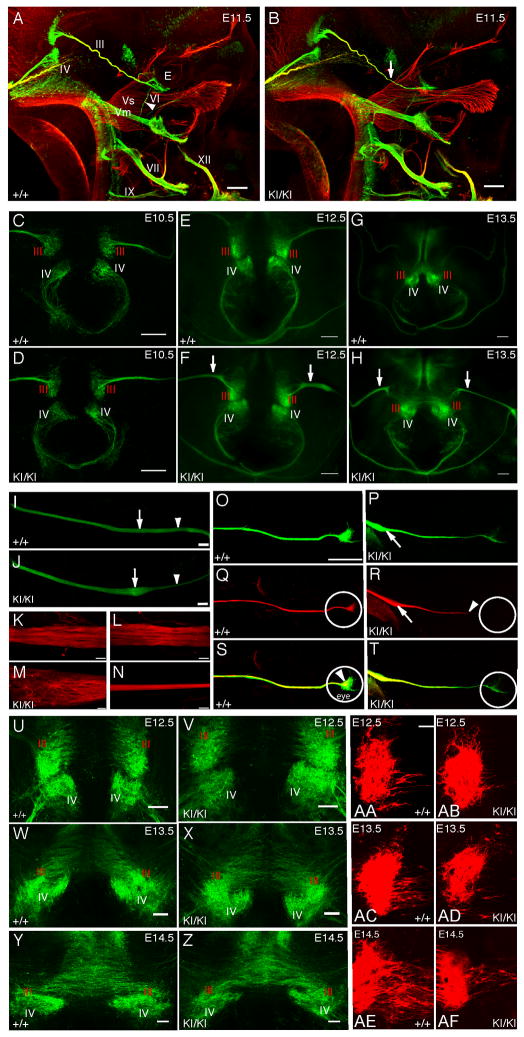

Figure 2. Oculomotor nerve pathology in Kif21aKI/KI mice.

(A–B) Whole mount fluorescent immunostaining with anti-NF (red) and anti-GFP (green) antibodies of E11.5 Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP (A) and Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP (B) embryos (n=22,20) reveal similar trajectories of WT and mutant cranial nerves. Arrowhead in (A) points to VI nerve; arrow in (B) highlights distal thinning of III nerve in the mutant compared to WT. Scale bar 200 μm. (C–H) Images of dorsal view of flat-mounted midbrain tissue from Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP (C, E, G) and Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP (D, F, H) embryos at E10.5 (C, D), E12.5 (E, F), E13.5 (G, H); n=5,5 for each age. Note the normal appearance of mutant III and IV nuclei and exiting nerves. At E12.5 and E13.5, mutant III nerve is thickened following exit into the periphery compared to WT (F, H, arrows). Scale bar 100 μm. (I, J) Confocal images of proximal III nerves oriented with brainstem to the left and orbit to the right from E12.5 Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP (I) and Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP (J) embryos reveal a bulb within the proximal nerve (arrow) followed by distal thinning (arrowhead) in all mutant and no WT nerves (n=20,20). Scale bar 100 μm. (K–N) Confocal images of WT and mutant III nerves stained with anti-NF antibody. (K) and (L) correspond to regions of arrow and arrowhead in (I), while (M) and (N) correspond to regions of arrow and arrowhead in (J) (n=3,3). Scale bars 20 μm. (O–T) Stitched images of multi-color anterograde labeled III axons in Kif21a+/+ (O, Q, S) and Kif21aKI/KI (P, R, T) at E12.5. OMNsd (Sd) contralateral neurons are red (Q, R), while both ipsilateral and contralateral neurons are green (O, P). When merged (S, T), Sd axons from the contralateral nucleus appear yellow, while ipsilateral OMNid (Id) axons remain green. Primarily contralateral yellow axons (T) terminate within the bulb (arrow in P, R) and along the nerve, failing to reach the developing eye (white circle) in Kif21aKI/KI but not Kif21a+/+ embryos (n=3,3) Scale bar 200 μm. (U–Z) Confocal images highlight normal nuclear formation and normal density of the axons of Sd motor neurons as they cross the midline in mutant versus WT mice (U–X are higher magnification of E–H). Scale bar 200 μm. (AA–AF) Ventricular view of flat-mounted midbrains with motor neurons in the OMN nucleus labeled retrogradely following dye application in the orbit of one eye of E12.5–E14.5 Kif21a+/+ (AA, AC, AE) or Kif21aKI/KI (AB, AD, AF) embryos (n=12,11). In WT embryos, dye fills the axons of the Sd motor neurons crossing the midline of Kif21a+/+ embryos. In contrast, in mutant embryos, fewer Sd axons are retrograde labeled from the orbit in Kif21aKI/KI embryos, despite similar density by GFP detection (refer to U–Z). Scale bar 30 μm. Abbreviations: III=OMN nerve, IV=trochlear nerve, Vs=sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve, Vm=motor branch of the trigeminal nerve, VI=abducens nerve, VII=facial nerve, IX=glossopharyngeal nerve, XI=accessory nerve, XII=hypoglossal nerve, E=eye, Sd=OMNsd, Id=OMNid.

See also Figure S2.

We asked if distal OMN nerve thinning in CFEOM1 resulted from errors in OMN neuron identity, but did not detect differences in molecular markers specific for their identity in Kif21aKI/KI versus WT mice (Figure S2C–S2D). Moreover, E10.5–E13.5 Kif21aKI fluorescent OMN and trochlear nuclei and trochlear nerves were indistinguishable from WT (Figure 2C–2H). Although mutant OMN axons appeared to exit the brainstem appropriately as multiple rootlets, at both E12.5 and E13.5 the proximal mutant nerves appeared thicker than WT (Figure 2E–2H).

To better visualize the developing nerve, Kif21a+/+, Kif21+IKI, and Kif21aKI/KI mutant fluorescent OMN nerves were dissected from E12.5 embryos and imaged (Figures 2I, 2J, S2E). We found that the nerve thickening ended within the first half of the peripheral nerve trajectory as a single smooth, circumscribed enlargement we refer to as the bulb. Distal to the bulb, each mutant nerve was thin. Most Kif21aKI/KI mice developed bulbs bilaterally, while Kif21+/KI mice typically had a thinner distal nerve but only a 50% incidence of bulb formation, and Kif21a+/+ mice had neither thinning nor bulbs. We stained fluorescent OMN nerves with anti-neurofilament (NF) antibody to better visualize single axons (Figures 2K–2N and S2F). Kif21aKI/KI axons proximal to the bulb had straight trajectories similar to WT. Within the bulb, a subset of axons pursued complex trajectories and appeared to terminate, while others maintained straight trajectories and exited the bulb to form the thin distal nerve.

We employed ex vivo anterograde and retrograde tracer studies to identify the axon population terminating within the bulb (Figure S2G–S2N). The bulb was detected by anterograde lipophilic dye labeling (Figure S2O–S2P), and we took advantage of the normal contralateral innervation pattern of the OMNsd to label OMNsd axons versus both OMNsd and OMNid axons using two dye colors (Figure 2O–2T). Two-color labeling revealed that the prematurely terminating axons were primarily those of the OMNsd, which originated from the contralaterally migrating OMN neuron population. Examination of E12.5–14.5 embryos (Figures 2U–2Z and also 3T) revealed that the migration of OMNsd cell bodies across the midline between E12.5–E14.5 appeared to proceed normally in Kif21aKI/KI mice. Thus, we attempted to retrograde label these crossing axons by placing dye in the developing orbit. A smaller subset of mutant motor neurons crossing the midline was labeled by retrograde dye compared to WT (Figures 2AA–2AF and S2Q–S2R), consistent with the termination of most OMNsd axons within the proximal nerve and bulb.

The developing distal Kif21aKI/KI oculomotor nerve superior division is hypoplastic while the inferior division develops aberrant branches

Kif21a+/+, Kif21a+IKI, and Kif21aKI/KI mutant fluorescent ocular nerves, together with surrounding tissue and orbit, were dissected from E12.5 IslMN:GFP embryos to visualize their complete trajectories. While the trochlear nerve appeared normal, the distal OMN and abducens nerves appeared thin (Figure 3A–3B), consistent with the loss of OMN and, to a lesser degree, abducens motor neurons in the mature animals. Moreover, the images confirmed proximal thickening, bulb formation, and distal thinning of the Kif21aKI/KI OMN nerve, and revealed hypoplasia of its developing distal OMNsd. The thin OMNsd was confirmed in an E14.5 Kif21a+IKI embryo by two-photon microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction (Supplemental Movies S1 and S2), consistent with its absence in the human CFEOM1 autopsy study (Engle et al., 1997).

Figure 3. Failure of oculomotor axon development is the primary defect in CFEOM1.

(A–J) Confocal images of ocular motor nerves dissected from Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP and Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP mice, with brainstem to the left and eye to the right. III nerve and its branches labeled in red text, IV and VI nerves labeled in yellow text. (A, B) Low magnification of ocular motor nerves from E12.5 WT (A) and mutant (B) mice; n=10, 10. Note the proximal bulb (*) and distal thinning of III with hypoplasia of the distal superior (Sd) and inferior (Id) divisions of the mutant nerve, and thinning of VI (arrowhead) compared to WT. Scale bars 200 μm. (C–J) Distal OMN nerves in WT (C, E, G, I) and mutant (D, F, H, J) mice at E11.5 (C, D), E12.5 (E, F), E13.5 (G, H), and E15.5 (I, J); n=10, 10 for each age. At E11.5, both WT and mutant nerves reach the orbit and appear to explore the local environment, but mutants have fewer exploring axons within the distal decision region (C, D). At E12.5, a small, defasciculated Sd protrudes from the WT nerve, and the Id exhibits an enlarged distal region with a subset of axons pursuing convoluted trajectories (E). In contrast, the E12.5 mutant nerve (F) has thinner Sd and Id, and several aberrant, fasciculated branches (arrows) emerge from the Id exploratory region. At E13.5, the WT nerve (G) has a more substantial Sd with several fasciculated bundles, while the mutant (H) Sd is thin or absent, and the Id exploratory region is small and has aberrant branches (arrow) as well as the normal branch to the IO. At E15.5, WT III (I) appears fully developed, with Sd branches to the SR and LPS. The Id now sends off several branches, presumably to the MR, IR, and IO. In comparison, mutant III (J) Sd is severely hypoplastic, while the Id is thin but sends off several stereotyped branches similar to WT, with no visible aberrant branches. Compared to WT, mutant VI was also hypoplastic compared to WT (arrow head) while mutant IV appeared normal. (K) Onset of Kif21a expression in EOMs during development. Immunostaining with anti-Kif21a antibody (red) and anti-Myo antibody (green) on coronal sections through the eye of E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5 WT mice. Kif21a is detected in the retina and in rootlets of many developing nerves (including III and VI, arrowheads) but is absent from green EOMs (arrows) until E14.5, subsequent to its neuronal expression. (L) Histological sections of the mouse orbit at E14.5 reveal proper size and positioning of EOMs in Kif21aKI/KI compared to Kif21a+/+ mice. (M–R) Fluorescent whole mount imaging of developing III nerves stained with anti-NF antibody (red) and anti-Tuj1 antibody (green) at E10.5 (M, N), E11.5 (O, P), and E12.5 (Q, R) from Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP WT (M, O, Q) and Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP mutant (N, P, R) embryos. Anti-Tuj1 staining was omitted from E12.5 because of high background at this age. Arrowheads and arrows indicate proximal and distal OMN nerve at points of measurement in (S). Scale bars 100μm. (S) Quantification of proximal (odd numbered solid bars) and distal (even numbered hatched bars) III nerve diameters in (M–R) from left and right OMN nerves from at least n=3 Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP (blue bars 1–6) and Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP (green bars 7–12) embryos at E10.5–E12.5. *Significant p-value < 0.004. P-values: 1:2<0.001*, 1:3=0.032, 1:5=0.000*, 1:7=0.098, 2:4<0.001*, 2:6<0.001*, 2:8=0.713, 3:4=0.010, 3:5=0.195, 3:9=0.335, 4:6=0.001*, 4:10=0.006, 5:6=0.148, 5:11=0.025, 6:12<0.001*, 7:8=0.007, 7:9=0.541, 7:11=0.004, 8:10=0.056, 8:12=0.037, 9:10<0.001*, 9:11=0.059, 10:12=0.990, 11:12=0.001*. (T) Increased apoptosis of III neurons is observed at E12.5 and 14.5 in Kif21aKI/KI (right) compared to Kif21a+/+ (left) mice. Note a similar proportion of Isl1-positive motor neurons crossing the midline (*) in WT and mutant mice, and an increase in Caspase3+ cells in Kif21aKI/KI embryos both within the III nuclei and in neurons crossing the midline at E14.5. (U) Quantification of Caspase3+ cells in Kif21a+/+ and Kif21aKI/KI embryos demonstrates increased apoptosis at E12.5–E14.5 in the III but not the IV nuclei; (n=4,4) at each stage. Caspase3+ neurons in the III nucleus bilaterally of WT versus Kif21aKI/KI were E11.5, 6±0.5 vs. 7 ±1; E12.5, 8±1 vs. 34±3; E13.5, 28±2 vs. 68±3; E14.5, 43±2 vs. 76±3; E15.5, 43±1 vs. 44±0.5; **p<0.001. Abbreviations: Sd=OMNsd, Id=OMNid, IO=inferior oblique branch, O=optic nerve and as per Figure 2.

Next, OMN nerves were dissected from E11.5–E15.5 embryos to define the normal and abnormal development of the distal superior and inferior branches (Figures 3C–3J). Visualizing the distal aspect of the nerve, we found that WT axons paused and followed complex trajectories prior to forming branches to innervate target EOM. This behavior is consistent with developing axonal populations arriving at ‘decision regions’ to turn or to enter a target in vivo, as documented in growth cones of chick spinal motor neurons within the plexus (Tosney and Landmesser, 1985), retinal ganglion cell at the optic chiasm (Mason and Erskine, 2000), and cortical neurons within the corpus callosum (Kalil et al., 2000). In mutants, the developing OMNsd was markedly thinner than that of WT nerves at all ages, while the OMNid appeared moderately thinner, with premature fasciculation into transient aberrant branches. At E15.5, the mutant abducens nerve was thinner while the trochlear appeared similar to wildtype.

Kif21aKI/KI oculomotor nerve pathology does not arise from a primary defect in EOM development, axon retraction, or motor neuron cell death

Next, we asked if the OMN pathology in Kif21aKI/KI mice, which begins prior to E12.5, could result from a primary defect in EOM development. We found, however, that while Kif21a expression in OMN neurons begins at E10 (Desai et al., 2012), expression in EOM began at E14.5 (Figure 3K), several days after the nerve pathology. We also found the position and size of the SR and LPS muscles appeared normal at E14.5 (Figure 3L), and that EOM hypoplasia began after P0, several days after EOM innervation was reduced (Figure 1L–1Q).

To confirm that the OMN bulb resulted from premature axon termination rather than axon retraction, we measured proximal and distal OMN nerve diameters in WT and mutant embryos at E10.5, E11.5, and E12.5 (Figure 3M–3S). The proximal diameter of the WT nerve at E10.5 was approximately twice that of its distal diameter, while by E11.5 there was no significant difference between them, likely reflecting the growth of additional axons along the WT nerve between E10.5 and E11.5. Neither proximal nor distal diameter of the mutant nerve differed significantly from WT at E10.5. In contrast to WT, however, the mutant proximal diameter increased significantly over time while the distal diameter did not, resulting in distal nerve thinning. This is consistent with a reduction in axon growth down the mutant nerve compared to WT after E10.5.

We hypothesized that the loss of OMN neurons in adult Kif21aKI/KI mice was secondary to failure of axon elongation, and examined their relative timing. OMN and trochlear motor neurons were co-labeled with Islet1 and activated Caspase3 (Cas3+) antibodies in both Kif21aKI/KI and Kif21a+/+ littermates at E11.5–E16.5 (Figure 3T–3U). Kif21a+/+ motor neurons underwent a wave of natural apoptotic cell death between E12.5–E15.5. At E11.5, when growth of Kif21aKI/KI OMNsd axons had already fallen behind Kif21a+/+, the number of Cas3+ positive cells in the OMN nucleus was similar to WT. From E12.5–E15.5, however, the number of Cas3+ positive OMN, but not trochlear, neurons in Kif21aKI/KI mice was significantly increased. Thus, Kif21aKI/KI OMN nerve growth failure precedes motor neuron apoptosis. Taken together, these findings support a neurogenic etiology for CFEOM1, with primary failure of axon elongation to the orbit.

Kif21aKI/KI bulb contains misdirected axons with enlarged growth cones and increased numbers of filopodia

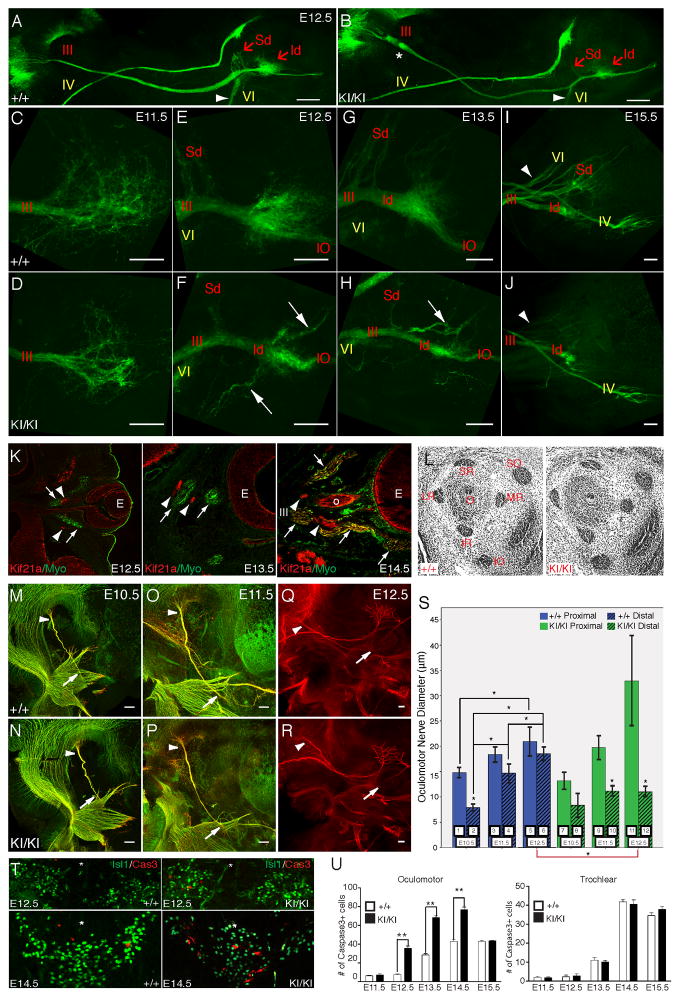

To examine the ultrastructure of the mutant bulb, E12.5 nerves from two mutant mice were examined in cross-section at levels within and just proximal and distal to the bulb, and compared to nerves from two WT mice at equivalent proximal and distal cross-sectional levels (Figure 4A–4E). Compared to the cross-sectional area of the proximal mutant nerve prior the bulb, the area within the bulb was increased 3.5–4 fold, while the area distal to the bulb was decreased 3-fold (Figure S3A), consistent with mutant OMN nerve distal thinning.

Figure 4. Ultrastructural analysis of developing oculomotor nerves in Kif21a+/+ and Kif21aKI/KI embryos.

(A–E) Stitched electron microscopy (EM) images (4800x) of E12.5 Kif21a+/+;IslMN:GFP (A, B) and E12.5 Kif21aKI/KI;IslMN:GFP (C, D, E) III nerve cross-sections. (A) and (C) are equivalent proximal levels while (B) and (D) are equivalent distal levels, and correspond to cross-sections of the nerve just proximal and distal to the bulb (E) in the mutant nerve. Scale bars 10 μm. (F–M) EM images (13000x) from cross-sections in (A–E). Proximal (F, H) and distal (G, I) sections of WT (F, G) and mutant (H, I) nerves consist primarily of axons running parallel to the nerve trajectory with a few central growth cones (stars) and lamellipodia/filopodia (asterisk). Cross-section of mutant bulb (J–M) contain highly disorganized axons and increased numbers of longitudinal axons (arrows), enlarged central growth cones (stars), lamellipodia/filopodia (asterisks), aggregation of mitochondria, membranes and vesicles (empty arrowheads), and degenerating axons (filled arrowheads). Scale bars 500 nm. (N, O) Stacked graphs showing numbers (N) and average areas (O) of cross-sectional, longitudinal, and degenerating axons, of central growth cones, and of lamellipodia/filopodia from two mutant and two WT III nerves at cross-sectional levels shown in A–E. The number/value for each object is provided within or above each fraction. #1 and #2 = WT nerves; #3 and #4 = mutant nerves; p=proximal; d=distal; b=bulb.

See also Figure S3.

For each of the five cross-sections (Figure 4A–4E), we counted and measured all objects and labeled them as axons cut in cross-section, axons cut longitudinally or obliquely, central growth cones, lamellipodia/filopodia, or degenerating axons (Figures 4F–4I, S3B–S3C). Proximal and distal sections of both WT and mutant nerves consisted primarily of axons running parallel to the nerve trajectory, with a small number of moderate-sized growth cones and lamellipodia/filopodia (Figure 4F–4I). WT nerves contained similar numbers of axons, and axon number did not vary greatly between proximal and distal levels. In contrast, the mutant nerves’ distal sections contained 55% fewer axons than proximal sections, and the proximal sections contained 18% fewer axons than WT proximal sections (Figures 4N, S3D). The moderate reduction in mutant nerve proximal axons likely reflects pathologic cell death in the E12.5 Kif21aKI/KI OMN nucleus (refer to Figure 3T and 3U), while the much greater reduction in mutant nerve distal axons is consistent with axon termination in the bulb.

To determine if CFEOM1 mutations visibly alter the distribution of organelles, we examined proximal nerve sections, as these included cross-sectional axons of the OMNsd destined to stall as well as OMNid axons destined to pass through the bulb (Figure S3B). We found no difference in the average densities of vesicles, membranes, or mitochondria between mutant and WT axons (Figure S3E S3F). These data support absence of a general disruption of axonal trafficking.

We examined bulb ultrastructure and found it to be highly disorganized, with many axons running perpendicular to the cross-sectional plane (Figure 4J–4M). Moreover, there was a remarkable increase in growth cone size, and in number of filopodia and degenerating axons (Figures 4N and 4O, S3D and S3G). These findings are again reminiscent of normal decision regions in which populations of axons change direction. Within such regions, growth cones cease forward movement, enlarge, extend multiple filopodia, and develop erratic-appearing trajectories prior to establishing the correct new direction of growth (Mason and Erskine, 2000). Taken together, our results suggest a model in which WT OMNsd axons normally reach the distal nerve, where they pause and explore the environment and then turn and fasciculate as its superior branch. In contrast, in the CFEOM1 disease state, our data suggest that these axons stall within the proximal nerve, where they explore the environment within the bulb region, fail to form an aberrant OMNsd, and then degenerate.

The Kif21aKI/KI CFEOM1 phenotype results from a gain of function mechanism

All reported CFEOM1 mutations are heterozygous, result in a single amino acid substitution or deletion in the motor or 3rd coiled-coil stalk of KIF21A (Figure1A) and cause indistinguishable human phenotypes. These genetic data strongly support altered KIF21A function underlying CFEOM1. We previously noted, however, that the level of R954W-mutant KIF21A protein in human CFEOM1 postmortem brain tissue lysates was reduced (Desai et al., 2012). Thus, we asked if loss of KIF21A function caused CFEOM1.

We examined Kif21aKI/KI brain lysates and found, similar to the human autopsy, that Kif21a protein levels were reduced 35%, 45%, and 60% compared to WT in E13.5, E18.5 and adult mice, respectively (Figure S4A), while Kif21a mRNA levels did not differ (Figure S4B, S4C). Thus, Kif21a mutant protein level appears highest during the embryonic period when CFEOM1 pathology occurs. To determine if the reduction of Kif21a protein in Kif21aKI/KI mice contributed to the CFEOM1 phenotype, we generated Kif21a knock-out mice by deleting much of the motor domain (Figure S4D–S4G). The resulting homozygous mice completely lacked full-length (FL) Kif21a, and harbored a very low level of a truncated Kif21a (Figure S4F) missing the motor domain necessary for motor-microtubule interaction and anterograde movement; we refer to them as Kif21a knockout-motor truncation mice (Kif21aKOMT). While the low level of truncated protein could act as a dominant negative, it existed at less than 15% of the WT protein level. Therefore, the mouse pathology should encompass any Kif21a loss-of-function phenotype. Kif21a+/KOMT mice were viable, appeared phenotypically normal, and none had the external CFEOM1 phenotype found in 43% of Kif21a+IKI mice. Although Kif21aKOMT/KOMT mice died within 24 hours of birth, the developing OMN nerve did not contain a bulb or distal thinning found in Kif21aKI/KI mice (Figure 5A–5H), and OMN neuron apoptosis was equivalent to WT mice (Figure 5I–5K). Thus, loss of FL WT Kif21a does not cause CFEOM1.

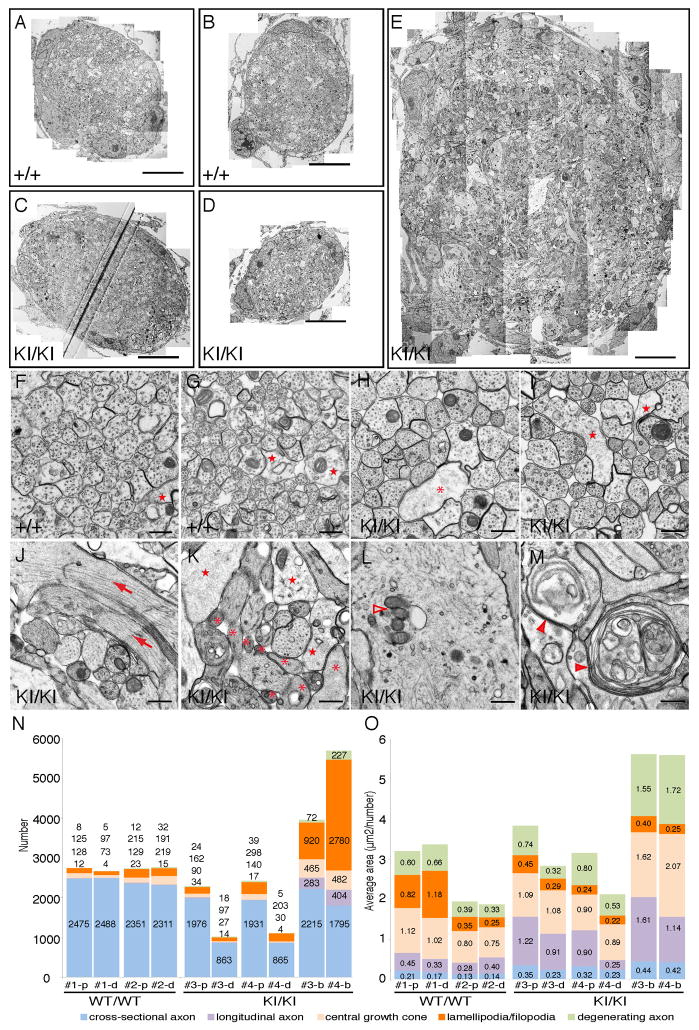

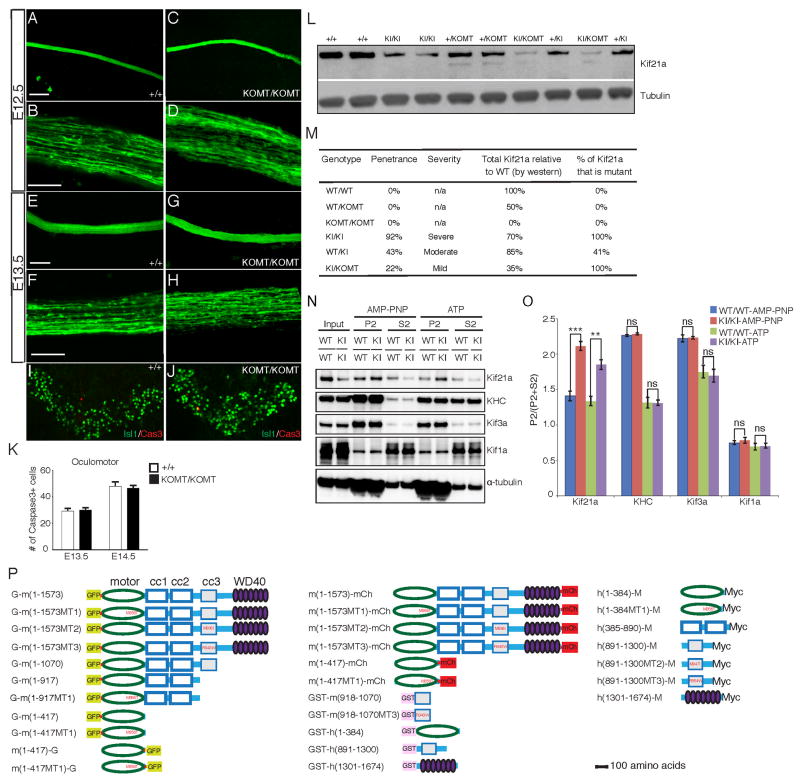

Figure 5. Loss of FL Kif21a does not cause CFEOM1.

(A–H) OMN anterograde dye tracer studies in Kif21a+/+ and Kif21aKOMT/KOMT embryos (n=10, 9), as shown for Kif21aKI/KI mice in Figure S2O, reveal normal exit, fasciculation, and trajectory of III axons and absence of a bulb or distal thinning at E12.5 (A–D) and E13.5 (E–H). Scale bars 100 μm (A, C, E, G), 20 μm (B, D, F, H). (I, J) Islet1 and Cas3+ immunohistochemistry of E14.5 WT (I) and Kif21aKOMT/KOMT (J) III nuclei reveal Islet1+ motor neurons crossing the midline and several Cas3+ apoptotic neurons. (K) Quantification of the number of Cas3+ cells in (I) and (J) reveal absence of pathological apoptosis in III nuclei of Kif21aKOMT/KOMT compared to Kif21a+/+ embryos at E13.5 (n=6,6, 29±2 vs. 30±2, p=0.206) and E14.5 (n=6,6, 48±3 vs. 46±2, p=0.334). (L) Representative western blot analysis of Kif21a protein levels in E18.5 brain tissues corresponding to genotypes in allelic series (n=4). Note lowest levels of Kif21a protein detected in Kif21aKI/KOMT mice. (M) Summary of genotypes and phenotypes from allelic analysis of Kif21a mutant mice. Percentages are relative to WT/WT mice. A 2X2 contingency table with Fisher’s exact test was used to determine differences in penetrance between Kif21aKI/KOMT and Kif21aKI/KI mice (p=0.0001). (N, O) E18.5 Kif21a+/+ or Kif21aKI/KI brain lysates were incubated with polymerized microtubules and AMP-PNP or ATP and microtubule co-sedimentation assays performed. Representative western blot (N) and quantification (O) show significantly increased relative levels of Kif21a in microtubule pellet fraction (P2) for endogenous mutant Kif21a compared to WT Kif21a (n=3). Mean ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ns=not significant. (P) Names and corresponding schematics of the FL and truncated Kif21a constructs. Kif21a domains are noted above the top left construct. Constructs containing mutant amino acid residues corresponding to MT1, MT2, or MT3 have the amino acid substitution represented in red font. Construct code names begin or end with the tag designation: “G-“ at the start denotes an N-terminal GFP tag, while “-G”, “-mCh”, or “-M” at the end denote a C-terminal GFP, mCherry, or Myc tag, respectively; “m” or “h” prior to the parenthesis denotes mouse or human construct, respectively; the number within the parentheses denotes the amino acid residues contained in the construct, and is followed by MT1, MT2, or MT3 if the construct contains a CFEOM1 amino acid substitution. Mouse and human constructs have slightly different amino acid numbering.

See also Figure S4.

To address whether absolute or relative levels of mutant Kif21a protein modulates penetrance of CFEOM1 in vivo, we crossed Kif21a+IKI and Kif21a+/KOMT mice to generate Kif21aKI/KOMT mice, which harbored the lowest levels of Kif21a protein (Figure 5L), of which all was mutant. Remarkably, Kif21aKI/KOMT mice survived, indicating one mutant copy of Kif21a, present at lower levels than one WT copy, is sufficient for survival, yet only 22% of Kif21aKI/KOMT adult mice had an external CFEOM1 phenotype and this phenotype was mild. Overall penetrance of the external CFEOM1 phenotype was 22% in Kif21aKI/KOMT compared to 92% in Kif21aKI/KI and 43% in Kif21a+IKI adult mice and, while Kif21aKOMT/KOMT mice do not survive, no Kif21aKOMT/KOMT embryo had CFEOM1 OMN nerve pathology (Figure 5M). These data suggest that the mouse is protected against CFEOM1 by reduced numbers of Kif21a dimers containing one or two mutant proteins. Thus, CFEOM1 penetrance correlates with the absolute amount of mutant Kif21a protein and is not rescued by WT protein, consistent with a gain-of-function mechanism.

Kif21a-microtubule association is regulated by interaction of the motor and 3rd coiled-coil domains, and CFEOM1 motor and stalk mutations disrupt this interaction

To explore how CFEOM1 mutations alter Kif21a function, we conducted in vivo cell fractionation of E18.5 Kif21a+/+ and Kif21aKI/KI brain tissue lysates and found enhanced association of mutant Kif21a with the cytoskeleton compared to WT (Figure S4H and S4I). Next, we co-sedimented Kif21a and polymerized microtubules from E18.5 Kif21a+/+ and Kif21aKI/KI brain tissue lysates. The relative amount of mutant Kif21a was significantly higher in the microtubule pellet (P2) fraction and lower in the soluble (S2) fraction compared to WT Kif21a (Figure 5N and 5O). These data support enhanced microtubule binding of endogenous mutant Kif21a in vivo.

To determine whether other CFEOM1 mutations and various Kif21a truncations would also enhance association of Kif21a with the microtubule cytoskeleton, we generated a series of Kif21a FL and truncated constructs (Figure 5P) into which we introduced one of the motor domain substitutions (MT1, M356T in both human and mouse) and two of the 3rd coiled-coil domain substitutions (MT2 and MT3, human M947I and R954W corresponding to mouse M936I and R943W, respectively). We confirmed that both FL WT and mutant Kif21a formed homodimers, and the amount of dimerized protein did not differ between them (Figure S5A). We then overexpressed the truncation and FL mutant constructs in HEK293 cells and co-sedimented Kif21a and polymerized microtubules from each cell lysate. Significantly more WT or MT1 stalk-truncated, as well as FL MT1, MT2, and MT3 mutant constructs were associated with the microtubule fraction compared to FL WT Kif21a (Figure 6A and 6B). Moreover, the increased association of the WT and MT1 truncation were indistinguishable. These changes in microtubule association were also directly visualized following overexpression of the constructs in HeLa cells (Figure S5B–S5E).

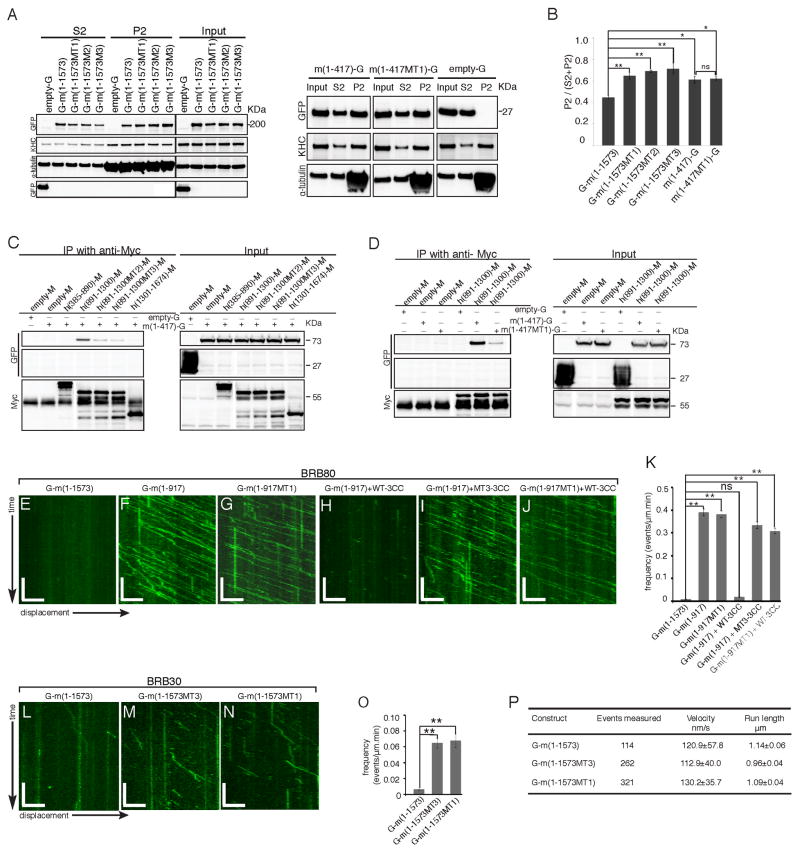

Figure 6. CFEOM1 mutations disrupt Kif21a intramolecular interactions between the motor and 3rdcoiled-coil domains, attenuate autoinhibition, and enhance Kif21a microtubule binding without altering run length or velocity.

(A and B) Mouse GFP-fused FL WT, MT1, MT2, or MT3 Kif21a, or stalk-truncated WT or MT1-mutant Kif21a was over-expressed in HEK293 cells, and microtubule co-sedimentation assays performed. Representative western blot (A, n=3) and quantification (B) show significantly increased relative levels in the microtubule pellet fraction (P2) of the three mutant FL Kif21a and both WT and MT1 stalk truncations compared to the WT FL Kif21a. Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ns=not significant. (C) Representative western blot (n=3) shows that over-expressed GFP-fused motor (G-m(1-417)) domain specifically co-immunoprecipitates with Myc-tagged 3rd coiled-coil (h(891-1300)-M) domain and not with 1st and 2nd coiled-coil (h(385-890)-M) or WD40 (h(1301-1674)-M) domain from HEK293 cell lysates using anti-myc antibody, and 3rd coiled-coil domain CFEOM1 mutations (MT2 and MT3) disrupt this co-immunoprecipitation. (D) Representative western blot (n=3) shows that introduction of the MT1 mutation into over-expressed GFP-fused motor domain disrupts immunoprecipitation with WT Myc-tagged 3rd coiled-coil domain from HEK293 cell lysates using anti-myc antibody. (E–J) Representative kymographs showing the displacement on a microtubule over 5 minutes in BRB80 motility buffer of mouse GFP-fused Kif21a: (E) WT FL; (F) WT truncation; (G) MT1-mutant truncation; (H) WT truncation plus 50uM purified WT 3rd coiled-coil domain; (I) WT truncation plus 50uM purified MT3 3rd coiled-coil domain; (J) MT1-mutant Kif21a truncation plus 50uM purified WT-3CC. Scale bars: x axis = 5 μm, y axis = 1min. (K) Quantification of (E–J) reveals Kif21a WT {G-m(1-917)} and mutant {G-m(1-917MT1)} truncations have significantly higher microtubule landing frequencies compared to that of Kif21a WT FL {G-m(1-1573)}. Purified WT-3CC inhibits landing frequencies of WT Kif21a truncation, while CFEOM1 mutations (MT1 and MT3) have a reduced inhibitory effect. (L–N) Representative kymographs showing the displacement on a microtubule over 5 minutes in BB30 motility buffer of mouse GFP-fused Kif21a: (L) WT FL; (M) MT3-mutant FL; and (N) MT1-mutant FL. Scale bars as per E–J. (O, P) Quantification of mouse WT FL or mutant (MT3 and MT1) FL Kif21a on microtubules for 10 minutes in BRB30 motility buffer reveals a significant increase in landing frequencies (O) of MT3 and MT1 mutant FL Kif21a compared to WT, but no significant changes in velocity or run length (P). For each construct, data were acquired from two independent experiments, and from three time-lapsed images for each experiment. Velocity: mean ± SD, run length: mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ns=not significant. Constructs are per Figure 5P.

The indistinguishable CFEOM1 phenotypes in humans (Demer et al., 2005; Yamada et al., 2003) and the increased Kif21a-microtubule association resulting from substitutions within either the KIF21A motor or 3rd coiled-coil domain led us to search for a single disease mechanism specific to these domains. Several kinesins have been demonstrated in vitro to autoregulate their activity by folding within a stalk linker region and stabilizing the folded conformation through intramolecular interactions (reviewed in (Verhey and Hammond, 2009)). Thus, we asked if WT Kif21a is similarly autoregulated, and if CFEOM1 mutations alter KIF21A autoinhibition. We performed co-immunoprecipitation, and found that the motor domain interacted only with the 3rd coiled-coil domain (Figures 6C, 6D and S5F). To determine whether this interaction regulated Kif21a function, we performed in vitro single-molecule fluorescence imaging assays using total internal reflection (TIRF) microscopy. In BRB80 buffer, few WT FL Kif21a bound to microtubules and moved processively, consistent with Kif21a existing primarily in an autoinhibited state (Figure 6E, Supplemental Movie S3). In contrast, both WT and MT1-mutant Kif21a truncated prior to the 3rd coiled-coil domain showed a significant increase in the number of active landing events (Figure 6F, 6G and 6K, Supplemental Movies S4 and S5). Moreover, there was no significant difference between the WT and MT1 truncation constructs, demonstrating that CFEOM1 motor mutations do not directly alter the ATP enzymatic activity or microtubule-binding motif. We then tested whether purified WT 3rd coiled-coil domain protein could block the microtubule-binding activity of the truncation construct. Indeed, WT truncated Kif21a active landing events were dramatically inhibited with the introduction of WT 3rd coiled-coil domain in trans (Figure 6H and 6K, Supplemental Movie S6).

Next, we asked if CFEOM1 mutations alter Kif21a autoinhibition. We found the interaction of the motor and 3rd coiled-coil was attenuated by the introduction of the MT1-motor or the MT2- or MT3-stalk mutations (Figures 6C and 6D, S5F and S5G). We repeated the single-molecule experiment combining either WT truncation with purified MT3-mutant 3rd coiled-coil protein, or MT1-mutant truncation with WT 3rd coiled-coil protein in trans. As predicted, both combinations failed to fully block the active landing events of truncated Kif21a (Figures 6I–K, S5H, Supplemental Movies S7 and S8). Moreover, introduction of the mutant constructs increased the ratio of active versus inactive (dead motor) landing events compared to WT (Figure S5I).

Lastly, we asked how CFEOM1 mutations alter FL Kif21a microtubule association and motile properties. While an increase in the frequency of active landing events of mutant Kif21a was evident in BRB80 buffer, run lengths were too short for accurate measurement (Figure S5J and S5K). Thus, we used BRB30, a lower ionic strength buffer that permitted quantification of both landing and motile properties. In contrast to FL WT Kif21a, both FL MT1- and MT3-Kif21a had a 10-fold increase in the frequency of active landing events (Figure 6L–6O, Supplemental Movie S9), while also decreasing the percentage of inactive landing events or dead motors (Figure S5L). We measured velocities and run lengths of active motors for all three FL constructs, and found no significant differences between them (Figure 6P).

Collectively, these data establish that Kif21a adopts an autoinhibited state through the direct and specific interaction of its motor and 3rd coiled-coil stalk domains, and reveal that this stalk-induced autoinhibition is partially released by CEFOM1 mutations, enhancing the association of Kif21a motors with microtubules for productive movement without altering the motor’s velocity and run length. Collectively, these data confirm and expand recently published in vitro data (van der Vaart et al., 2013). We also provide in vivo evidence of attenuated autoinhibition by CFEOM1-Kif21a motor and stalk mutations.

Kif21aKI/KI oculomotor explant axons have normal growth, but enlarged growth cones and increased filopodia

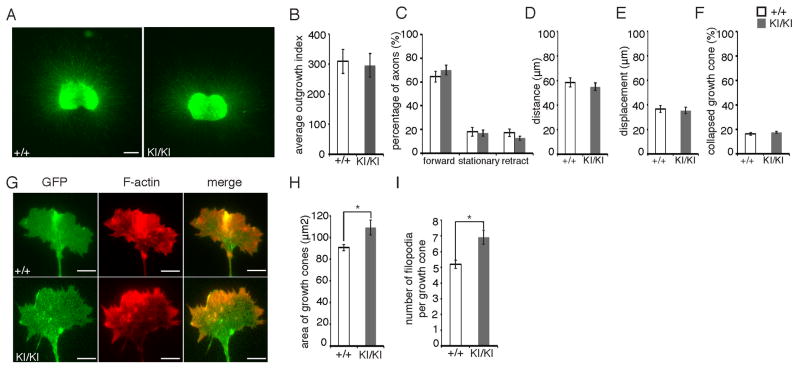

Despite wide expression of Kif21a, CFEOM1 pathology is restricted to OMN axons. Thus, we cultured OMN nuclei from Thy1:GFP and IslMN:GFP mice and examined the growth of GFP positive OMN axons in WT versus Kif21aKI/KI explant cultures. There were no significant differences in overall growth characteristics or percent of axons with collapsed growth cones (Figure 7A–7F).

Figure 7. Oculomotor growth cones in Kif21aKI/KI explant cultures have increased growth cone size and number of filopodia.

(A) Representative immunofluorescent images showing Thy1:GFP WT and Kif21aKI/KI OMN explants cultured for 3 days. Scale bars 400 μm. (B) Quantification of axon outgrowth from (A) shows no significant differences in OMN axon outgrowth between WT/WT and KI/KI mice (n=5,3). Mean ± SEM. (C–F) Percentage of growth cones with forward, stationary, or retracted movements (C), forward distance travelled (D), total displacement (E), and percent collapse (F) quantified from 30 minute recordings of IslMN:GFP Kif21aKI/KI and WT OMN explants cultured for 17–20 hours. No significant differences between WT and Kif21aKI/KI mice were detected (n=9,8). Mean ± SEM. (G) Representative immunofluorescent images of phalloidin-stained WT and Kif21aKI/KI OMN axon growth cones in explants cultured for 18 hours from the IslMN:GFP mice. Scale bars 5 μm. (H, I) Quantification of (G) reveals a significant increase in growth cone area (H) and number of filopodia per growth cone (I) of Kif21aKI/KI explants compared to WT (n=4 explants and 164 growth cones, n=3 explants and 139 growth cones). Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05.

See also Figure S6.

We next examined the OMN growth cones by immunohistochemistry in fixed explants cultured for 18 hours. We found a moderate but significant increase in both growth cone area and number of filopodia per growth cone in Kif21aKI/KI explants compared to WT (Figure 7G–7I). Kif21a is recruited by Kank1 to the cell cortex in vitro (van der Vaart et al., 2013), and overexpressed CFEOM1-mutant KIF21A enhances Kif21a-Kank1 interaction in vitro (Kakinuma and Kiyama, 2009). Thus, we compared the fluorescent intensity ratio in the OMN growth cone versus cell body of both Kif21a and Kank1, but found no differences in either ratio between WT and Kif21aKI/KI explants (Figure S6A–S6D). These data support mild attenuation, but not complete ablation of Kif21a autoinhibition. Moreover, while enlarged growth cones with increased numbers of filopodia in vitro likely share a common pathogenesis with bulb formation by mutant OMN axons in vivo, the in vitro phenotype is much milder, supporting an important environmental contribution to the development of CFEOM.

CFEOM3-causing TUBB3 missense mutations stabilize yeast microtubules and alter Kif21a-microtubule interactions (Tischfield et al., 2010). Thus, we asked if we could detect a difference in microtubule plus-end behavior by tracking EB3 protein following overexpression of WT versus mutant Kif21a in COS7 cells. Although WT Kif21a decreased microtubule polymerization rate and microtubule dynamics slightly but significantly compared to the control, consistent with recently reported data (van der Vaart et al., 2013), we did not detect a significant difference between the behavior of WT and CFEOM1-mutant Kif21a (Figure S6E–H).

Endogenous Kif21a and MAP1B interact, and Map1b−/− mice have CFEOM

To identify additional Kif21a-interacting partners that could play a role in the pathogenesis of CFEOM1, we immunoprecipitated E18.5 WT brain lysates with IgG and with three different anti-Kif21a antibodies, each of which recognized a distinct region of the Kif21a protein, and then performed mass spectrometry (data not shown). One consensus candidate we identified was the microtubule-associated protein 1b (Map1b) heavy chain, a major cytoskeletal protein essential for axon development in vivo. There are intriguing similarities between loss of Map1b function and our Kif21aKI/KI data. Loss of Map1b impairs growth cone turning in vitro and axon guidance in vivo (Bouquet et al., 2004; Mack et al., 2000; Meixner et al., 2000). Cultured Map1b−/− neurons have increased growth cone area and number of filopodia, and altered microtubule dynamics with longer pauses and fewer catastrophes (Gonzalez-Billault et al., 2002; Tortosa et al., 2013; Tymanskyj et al., 2012). Finally, the eyes of Map1b−/− mouse models are reported to appear ptotic and retracted (Meixner et al., 2000; Takei et al., 1997; Edelmann et al., 1996).

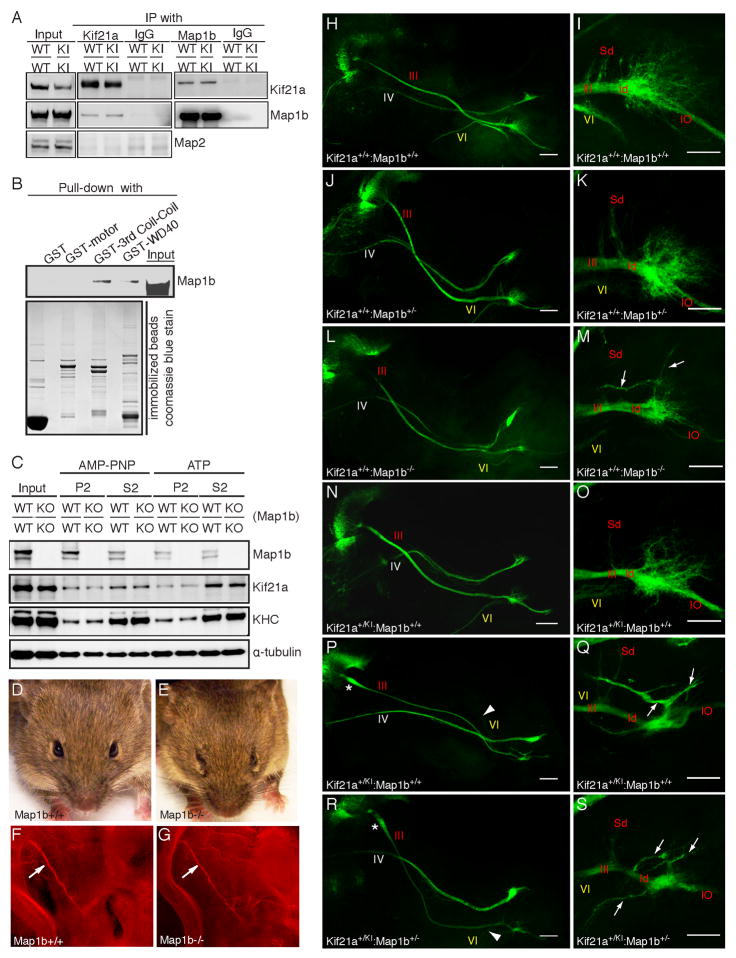

To explore a potential role of Map1b in CFEOM1, we confirmed the interaction of Map1b with WT Kif21a in E18.5 brain tissue lysates, and then determined that endogenous WT and CFEOM1-mutant Kif21a interacted equally well with Map1b by co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 8A). A GST pull-down assay demonstrated that Kif21a interacted with Map1b through its 3rd coiled-coil stalk and WD40 domains (Figure 8B). Furthermore, we performed a microtubule co-sedimentation assay with E18.5 WT and Map1b−/− brain tissue lysates. Loss of Map1b did not generally disrupt microtubule polymerization, nor did it alter the level of WT Kif21a or KHC bound to microtubules (Figure 8C), suggesting Map1b does not regulate the autoinhibition of Kif21a-microtubule interactions.

Figure 8. Endogenous Kif21a and MAP1B interact, Map1b−/− mice have CFEOM, and the penetrance of the oculomotor phenotype is greater in Map1b+/−.

;Kif21a+/KI compared to single heterozygous embryos.

(A) E18.5 WT and Kif21aKI/KI brain lysates immunoprecipitated with control IgG, anti-Kif21a antibody, or anti-Map1b antibody and subjected to Western blotting using the antibodies indicated. WT and mutant Kif21a interact equally with Map1b in both directions, but do not interact with Map2. (B) Western blot of GST-pull down of E18.5 WT brain lysates by purified GST-motor, GST-Kif21a-3rd coiled-coil and -WD40 domains. Kif21a interacts with Map1b through its 3rd coiled-coil and WD40 domains. (C) E18.5 Map1b+/+ or Map1b−/− brain lysates were incubated with AMP-PNP or ATP and microtubule co-sedimentation assays were performed. Western blot shows similar relative levels of Kif21a and KHC in the microtubule pellet fraction (P2). (D, E) Map1b+/+ mice have normal eyes (D), while Map1b−/− mice have globe retraction and ptosis (E). (F, G) Fluorescent whole-mount imaging of E11.5 III nerve (arrow) from Map1b+/+ (F) and Map1b−/− mice (G) stained with anti-NF antibody (red). The nerves have similar trajectories (n=4, 4). (H–S) Confocal images of III, IV, and VI nerves (left column) and higher magnification of the distal III nerve (right column) from E12.5 IslMN:GFP embryos, oriented and labeled as described in Figure 3A–3J, with VI nerve (arrowhead), aberrant III nerve branches (arrows), OMN bulb (*). WT (H, I), Map1b+/− (J, K), Map1b−/− (L, M), Kif21a+/KI (N–Q), double heterozygous Kif21a+/KI:Map1b+/− mice (R, S); n=10,10 for each genotype. Scale bars 200 μm (H, J, L, N, P, R) and 100 μm (I, K, M, O, Q, S). Abbreviations as per Figure 2.

We next examined the external eye phenotype of Map1b−/− mice and found that it closely resembled the Kif21aKI CFEOM1 phenotype and was also ~90% penetrant (Figure 8D and 8E). The trajectory of the OMN nerve appeared normal, similar to Kif21aKI mice (Figure 8F and 8G). We then generated Map1b+/−;IslMN:GFP and Map1b−/−;IslMN:GFP mice to examine the developing OMN nerve in finer detail. Compared to WT (Figure 8H, 8I), all Map1b+/− OMN nerves appeared normal (Figure 8J, 8K), while 90% of Map1b−/− nerves had mild proximal thickening in the absence of a bulb, distal thinning, hypoplasia of the OMNsd, and a smaller OMNid (Figure 8L, 8M). Moreover, ~30% of Map1b−/− distal OMN nerves had aberrant, long, fasciculated branches that emerged from the OMNid exploratory region (Figure 8M). In contrast, while ~50% of Kif21a+/KI distal OMN nerves had only mild proximal thickening and distal thinning compared to WT (Figure 8N, 8O), the other 50% had proximal bulbs and significant distal nerve hypoplasia and branching defects (Figure 8P, 8Q), as described for Kif21aKI/KI embryos (Figure 3B and 3F).

Finally, we asked if the interaction of Map1b and Kif21a was physiologically relevant by examining the OMN nerve of double heterozygous mice. Further analysis revealed that penetrance of the bulb phenotype (found in no Map1b+/− or Map1b−/− mice and in ~50% of Kif21a+IKI mice) rose to 90% in Map1b+/−; Kif21a+IKI;IslMN:GFP mice, and their distal nerve pathology resembled the more severely affected Kif21a+IKI and Kif21aKI/KI mice. The penetrance of abducens nerve hypoplasia also rose from ~50% in Kif21a+/KI to ~90% in double heterozygous Kif21a+/KI:Map1b+/− mice while the trochlear nerve appeared normal in all crosses. Taken together, the Map1b−/− OMN nerve innervation defects closely phenocopy the CFEOM1-mutant Kif21aKI nerve, both Map1b−/− and Kif21aKI mice develop CFEOM, and analysis of double heterozygous mice supports a genetic interaction between Map1b and Kif21a in CFEOM.

DISCUSSION

Since first described in the late 1800’s (Heuck, 1879), the etiology of CFEOM1 has been unknown, and whether it was primarily neuropathic or myogenic remained unclear. By introducing the most common CFEOM1 KIF21A missense mutation into mice, we recapitulate the human phenotype in both heterozygous and homozygous states. Analysis of Kif21aKI mice reveals that the CFEOM1 phenotypes of ptosis and restricted upgaze reflect failure of LPS and SR innervation secondary to developmental stalling of their growing OMNsd axons, while variably restricted and aberrant horizontal movements likely result from more subtle errors in innervation of the OMNid muscles. These studies establish a neurogenic etiology for CFEOM1.

Kinesin motor proteins are important for many aspects of neuronal development, and it is presumed that their activities need to be tightly regulated. Our data confirm that Kif21a can adopt a preferred autoinhibited state that requires the interaction of the lateral motor and 3rd coiled-coil stalk domains, and an active state in which this interaction has been released and Kif21a binds to the microtubule. CFEOM1 mutations attenuate Kif21a autoinhibition by disrupting this interaction, enhancing Kif21a association with microtubules without altering velocity or run length. This provides a single unifying molecular mechanism for both motor and stalk mutations to account for the indistinguishable human phenotypes.

While perturbed kinesin autoinhibition in worm, fungus, and fly in vivo are reported to cause loss-of-function phenotypes (Imanishi et al., 2006; Moua et al., 2011; Seiler et al., 2000), we find that loss of KIF21A function does not cause CFEOM1, and attenuated Kif21a autoinhibition resulting from CFEOM1 mutations does not result in the Kif21a null phenotype. Together, our data support gain-of-function mutations underlying CFEOM1, and suggest that both homozygous and heterozygous mutant dimers can disrupt Kif21a autoinhibition. Notably, while most human mutations in other kinesins cause partial or complete loss of function, mutations in KIF22 and KIF5A highlight specific residues that could prove important for autoregulation (Boyden et al., 2011; Crimella et al., 2012). Thus, pathological alterations of autoinhibition may extend beyond KIF21A and represent a more generalized mechanism underlying disorders of kinesin function.

Despite the broad expression of Kif21a (Desai et al., 2012) and its attenuated autoinhibition by CFEOM1 mutations both in vivo and in vitro, it is intriguing that these mutations selectively target ocular motor neuron development. These vulnerable OMN axons appear to form a pathological decision region defined by stalled axons with enlarged growth cones and turning defects, similar to the behavior of WT OMN axons when they enter a distal decision region near the orbit, as well for other axon populations within decision regions for turning (Mason and Erskine, 2000). We have found that Kif21a interacts with the Map1b heavy chain through its 3rd coiled-coil and WD40 domains, and that Kif21aKI/KI and Map1b−/− embryos have similar OMN nerve pathology that results in CFEOM and is accentuated in the double heterozygous state. Similar to our findings in Kif21aKI/KI neurons, others have shown aberrant turning behavior and enlarged growth cones in Map1b−/− neurons (Bouquet et al., 2004; Gonzalez-Billault et al., 2002; Mack et al., 2000; Tortosa et al., 2013). Moreover, both Map1b and Kif21a can regulate microtubule dynamics in neuronal growth cones (Tortosa et al., 2013; Tymanskyj et al., 2012; van der Vaart et al., 2013). Thus, the interaction between these two proteins is likely to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of CFEOM1. Combined with our previous reports of CFEOM3 arising from mutations in either TUBB3 or TUBB2B (Cederquist et al., 2012; Tischfield et al., 2010), these data highlight a selective vulnerability of the developing OMN nerve to perturbations of the axon cytoskeleton.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Detailed procedures are described in the Supplemental Information.

Transgenic mice

Detailed description of targeting strategy and generation of Kif21aKI/KI and Kif21aKOMT/KOMT can be found in Supplemental Information. 129S1 Kif21aKI and 129S1 Map1bKO mice were crossed to B6/129S1 IslMN:GFP (Lewcock et al., 2007) or Thy1:GFP reporter mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) and studied following a minimum of 4 backcrosses to 129S1. All animal work was performed in compliance with Boston Children’s Hospital IACUC Protocols.

Embryo dissection, immunohistochemistry, and ultrastructural analysis

Briefly, for immunohistochemistry, embryos and adult mice were dissected and fixed in 4% PFA. After blocking with serum, whole embryos or dissected tissues were sequentially incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. For ultrastructural analysis, embryos were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.02% CaCl2, and 2% tannic acid in 0.1M cacodylate buffer at RT, and a tissue block containing the OMN nerve was prepared for electron microscopy.

Anterograde and Retrograde Labeling

Anterograde and retrograde labeling of E14.5 and P0 ocular cranial nerves and EOMs were performed by placing NeuroVue® Maroon (red) or Jade (green) dye (MTTI, West Chester, Pennsylvania) soaked filter strips at specific axial levels of the brainstem or orbit. After dye diffusion, brainstems or orbits were observed for successful dye placement and completely labeled samples were prepared for confocal microscopy. Consecutive scans and stacks of images through the nerve and/or each nucleus were collected using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

Microtubule co-sedimentation assay

Microtubule co-sedimentation assay was performed as described previously (Tischfield et al., 2010) with modifications detailed in Supplemental Information. Clarified lysates in BRB80 buffer of E18.5 WT and mutant brains or HEK293 cells overexpressing WT or mutant Kif21a constructs were incubated with polymerized microtubules, palitaxol and AMP-PNP or ATP at 37°C, centrifuged at 55,000 rpm at 25°C, and then subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot.

Co-immunoprecipitation, protein purification and GST pull-down

Clarified lysates in lysate buffer (50mM TrisHCl, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% NP40, pH 6.8) of E18.5 WT and mutant brains or HEK293 cells overexpressing WT or mutant Kif21a constructs were incubated with antibody and protein-G agarose beads with gentle rotation at 4 °C overnight. After washing with lysate buffer, denatured elutions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot. For GST pull-down, GST-fused proteins were expressed and purified from E. Coli BL21 cells with glutathione sepharose beads. Clarified lysates (as described above) were incubated with protein-bounded beads at 4°C for 4h. The final denatured elutions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot. For in vitro single molecule motility assays described below, thrombin was used to cleave off the GST tag.

In vitro single molecule motility assays

Single molecule assays of GFP-fused WT or mutant Kif21a constructs were performed in motility chambers as previously described (Qiu et al., 2012). Coverslips were sequentially coated with 1 mg/ml biotin-BSA and 0.5 mg/ml streptavidin to immobilize Taxol-stabilized Cy5-microtubules. Clarified cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were diluted in motility buffer and added to the chamber. Images were recorded every 2s for 5 or 10min using an Olympus IX-81 TIRF microscope.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S Pfaff for IslMN:GFP reporter mice; N Copeland, S O’Gorman, G Banker, JS Liu and J-F Brunet for reagents; M Thompson, A Hill, G Gunner, and Boston Children’s Hospital IDDRC (P30 HD18655); Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (P30 CA06516); E Raviola, E Benecchi of the Harvard Neurobiology Electron Microscopy Facility; and L Ding of the Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center’s Enhanced Imaging Core for technical assistance. T Chu, MA Tischfield, S Hung, Z C Yip, A Formanek, D Hooker, C Anyaeji, P Wang, LA Lowery, C Manzini, and Engle lab members for assistance and thoughtful discussions. This work was also supported by R01EY013583 (E.C.E.), P30-HD18655, Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, Children’s Hospital Ophthalmology Foundation (Discovery Award), and a generous donation from the Hisham El-Khazindar family. E.C.E. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bouquet C, Soares S, von Boxberg Y, Ravaille-Veron M, Propst F, Nothias F. Microtubule-associated protein 1B controls directionality of growth cone migration and axonal branching in regeneration of adult dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7204–7213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2254-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ED, Campos-Xavier AB, Kalamajski S, Cameron TL, Suarez P, Tanackovic G, Andria G, Ballhausen D, Briggs MD, Hartley C, et al. Recurrent dominant mutations affecting two adjacent residues in the motor domain of the monomeric kinesin KIF22 result in skeletal dysplasia and joint laxity. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:767–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederquist GY, Luchniak A, Tischfield MA, Peeva M, Song Y, Menezes MP, Chan WM, Andrews C, Chew S, Jamieson RV, et al. An inherited TUBB2B mutation alters a kinesin-binding site and causes polymicrogyria, CFEOM and axon dysinnervation. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5484–5499. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WM, Andrews C, Dragan L, Fredrick D, Armstrong L, Lyons C, Geraghty MT, Hunter DG, Yazdani A, Traboulsi EI, et al. Three novel mutations in KIF21A highlight the importance of the third coiled-coil stalk domain in the etiology of CFEOM1. BMC Genet. 2007;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimella C, Baschirotto C, Arnoldi A, Tonelli A, Tenderini E, Airoldi G, Martinuzzi A, Trabacca A, Losito L, Scarlato M, et al. Mutations in the motor and stalk domains of KIF5A in spastic paraplegia type 10 and in axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2. Clin Genet. 2012;82:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Clark RA, Engle EC. Magnetic resonance imaging evidence for widespread orbital dysinnervation in congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles due to mutations in KIF21A. Invest. Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:530–539. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai J, Velo MP, Yamada K, Overman LM, Engle EC. Spatiotemporal expression pattern of KIF21A during normal embryonic development and in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 (CFEOM1) Gene Expr Patterns. 2012;12:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann W, Zervas M, Costello P, Roback L, Fischer I, Hammarback JA, Cowan N, Davies P, Wainer B, Kucherlapati R. Neuronal abnormalities in microtubule-associated protein 1B mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1270–1275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle EC, Goumnerov BC, McKeown CA, Schatz M, Johns DR, Porter JD, Beggs AH. Oculomotor nerve and muscle abnormalities in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:314–325. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Billault C, Owen R, Gordon-Weeks PR, Avila J. Microtubule-associated protein 1B is involved in the initial stages of axonogenesis in peripheral nervous system cultured neurons. Brain Res. 2002;943:56–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuck G. Ueber angeborenen vererbten Beweglichkeits - Defect der Augen. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1879;17:253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi M, Endres NF, Gennerich A, Vale RD. Autoinhibition regulates the motility of the C. elegans intraflagellar transport motor OSM-3. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:931–937. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinuma N, Kiyama R. A major mutation of KIF21A associated with congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 (CFEOM1) enhances translocation of Kank1 to the membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;386:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil K, Szebenyi G, Dent EW. Common mechanisms underlying growth cone guidance and axon branching. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewcock JW, Genoud N, Lettieri K, Pfaff SL. The ubiquitin ligase Phr1 regulates axon outgrowth through modulation of microtubule dynamics. Neuron. 2007;56:604–620. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Zhao C, Zhao K, Li N, Larsson C. Novel and recurrent KIF21A mutations in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 and 3. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:388–394. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack TG, Koester MP, Pollerberg GE. The microtubule-associated protein MAP1B is involved in local stabilization of turning growth cones. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:51–65. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek JR, Weiner JA, Farlow SJ, Chun J, Goldstein LS. Novel dendritic kinesin sorting identified by different process targeting of two related kinesins: KIF21A and KIF21B. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:469–479. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason C, Erskine L. Growth cone form, behavior, and interactions in vivo: retinal axon pathfinding as a model. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:260–270. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(200008)44:2<260::aid-neu14>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meixner A, Haverkamp S, Wassle H, Fuhrer S, Thalhammer J, Kropf N, Bittner RE, Lassmann H, Wiche G, Propst F. MAP1B is required for axon guidance and Is involved in the development of the central and peripheral nervous system. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1169–1178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moua P, Fullerton D, Serbus LR, Warrior R, Saxton WM. Kinesin-1 tail autoregulation and microtubule-binding regions function in saltatory transport but not ooplasmic streaming. Development. 2011;138:1087–1092. doi: 10.1242/dev.048645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusky GT, Alam NM, Beekman S, Douglas RM. Rapid quantification of adult and developing mouse spatial vision using a virtual optomotor system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4611–4616. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Derr ND, Goodman BS, Villa E, Wu D, Shih W, Reck-Peterson SL. Dynein achieves processive motion using both stochastic and coordinated stepping. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:193–200. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler S, Kirchner J, Horn C, Kallipolitou A, Woehlke G, Schliwa M. Cargo binding and regulatory sites in the tail of fungal conventional kinesin. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:333–338. doi: 10.1038/35014022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener EC, Lee BA, Turgut B, Akarsu AN, Engle EC. A clinically variant fibrosis syndrome in a Turkish family maps to the CFEOM1 locus on chromosome 12. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1090–1097. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.8.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Kondo S, Harada A, Inomata S, Noda T, Hirokawa N. Delayed development of nervous system in mice homozygous for disrupted microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B) gene. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1615–1626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischfield MA, Baris HN, Wu C, Rudolph G, Van Maldergem L, He W, Chan WM, Andrews C, Demer JL, Robertson RL, et al. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. Cell. 2010;140:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortosa E, Galjart N, Avila J, Sayas CL. MAP1B regulates microtubule dynamics by sequestering EB1/3 in the cytosol of developing neuronal cells. EMBO J. 2013;32:1293–1306. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosney KW, Landmesser LT. Growth cone morphology and trajectory in the lumbosacral region of the chick embryo. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2345–2358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-09-02345.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymanskyj SR, Scales TM, Gordon-Weeks PR. MAP1B enhances microtubule assembly rates and axon extension rates in developing neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;49:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart B, van Riel WE, Doodhi H, Kevenaar JT, Katrukha EA, Gumy L, Bouchet BP, Grigoriev I, Spangler SA, Yu KL, et al. CFEOM1-associated kinesin KIF21A is a cortical microtubule growth inhibitor. Dev Cell. 2013;27:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhey KJ, Hammond JW. Traffic control: regulation of kinesin motors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:765–777. doi: 10.1038/nrm2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Li S, Xiao X, Guo X, Zhang Q. KIF21A novel deletion and recurrent mutation in patients with congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles-1. Int J Mol Med. 2011;28:973–975. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Andrews C, Chan WM, McKeown CA, Magli A, De Berardinis T, Loewenstein A, Lazar M, O’Keefe M, Letson R, et al. Heterozygous mutations of the kinesin KIF21A in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 (CFEOM1) Nat Genet. 2003;35:318–321. doi: 10.1038/ng1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Chan WM, Andrews C, Bosley TM, Sener EC, Zwaan JT, Mullaney PB, Ozturk BT, Akarsu AN, Sabol LJ, et al. Identification of KIF21A Mutations as a Rare Cause of Congenital Fibrosis of the Extraocular Muscles Type 3 (CFEOM3) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2218–2223. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.