Abstract

Objective:

This study investigated whether self-reports of alcohol-related postings on Facebook by oneself or one’s Facebook friends were related to common motives for drinking and were uniquely predictive of self-reported alcohol outcomes (alcohol consumption, problems, and cravings).

Method:

Pacific Northwest undergraduates completed a survey of alcohol outcomes, drinking motives, and alcoholrelated Facebook postings. Participants completed the survey online as part of a larger study on alcohol use and cognitive associations. Participants were randomly selected through the university registrar’s office and consisted of 1,106 undergraduates (449 men, 654 women, 2 transgender, 1 declined to answer) between the ages of 18 and 25 years (M = 20.40, SD = 1.60) at a large university in the Pacific Northwest. Seven participants were excluded from analyses because of missing or suspect data.

Results:

Alcohol-related postings on Facebook were significantly correlated with social, enhancement, conformity, and coping motives for drinking (all ps < .001). After drinking motives were controlled for, self–alcohol-related postings independently and positively predicted the number of drinks per week, alcohol-related problems, risk of alcohol use disorders, and alcohol cravings (all ps < .001). In contrast, friends’ alcohol-related postings only predicted the risk of alcohol use disorders (p < .05) and marginally predicted alcohol-related problems (p = .07).

Conclusions:

Posting alcohol-related content on social media platforms such as Facebook is associated with common motivations for drinking and is, in itself, a strong predictive indicator of drinking outcomes independent of drinking motives. Moreover, self-related posting activity appears to be more predictive than Facebook friends’ activity. These findings suggest that social media platforms may be a useful target for future preventative and intervention efforts.

“I will take a shot for every ‘like’ I get on this status.” —Anonymous Facebook user

Similar comments and photos referencing alcohol appear frequently on social networking sites such as Facebook (Moreno et al., 2009); should we dismiss these references as mere “self-presentation” or are they indicative of real-life behaviors? Alcohol use continues to be a serious issue in college populations (Johnston et al., 2010; Perkins, 2002), while concerns about social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, and MySpace) and sharing potentially inappropriate content (including comments and photos of alcohol and/or other drug use) in this age group have grown. Use of social media in general, and Facebook in particular, is widespread among college students, with more than 75% of the U.S. college population reporting active use of a Facebook account (Lenhart et al., 2010). Social media sites such as Facebook are rapidly expanding the boundaries of socialization and may provide an outlet for interacting with friends, fitting in with peers, coping with distress, and simply having fun (To-sun, 2012; Yang and Brown, 2013)—all of which have been associated with problematic drinking among young adults. Given the seriousness of alcohol issues facing this age group and the ubiquity and importance of social media use, it is important to investigate the role that content on sites such as Facebook may play in predicting and explaining college drinking outcomes.

Social networking and alcohol use

Posting alcohol-related content on Facebook may be related to real-life alcohol outcomes because of the self-representational (i.e., what you post) and social influence (i.e., what you see your friends posting) aspects of Facebook. If content on Facebook reflects a person’s real-life behaviors, alcohol-related content posted by or about an individual may provide an informal proxy record of his or her hazardous drinking. On one hand, such content may also be related to well-established motives for real-life drinking. On the other hand, exposure to the activity of one’s Facebook friends may in itself be influential. An individual who frequently sees alcohol-related posts by his or her Facebook friends may be more likely to adopt those behaviors or attitudes toward drinking. Although the self-representational aspect likely plays a more direct role between alcohol-related Facebook use and drinking behavior, examining the potential influence of friends’ postings may clarify how online social influence plays a role in drinking.

Despite the increasingly important role of social networking sites in college students’ lives, only a handful of studies have examined the relationship between online social networking sites and college students’ alcohol use. These studies have found that alcohol-related content on Facebook is common (Moreno et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2010), particularly among male college students (Egan and Moreno, 2011). Alcohol-related content on individuals’ profiles predicts scores on clinical measures of risk for alcoholism (Morgan et al., 2010; Ridout et al., 2012), alcohol-related problems (Ridout et al., 2012), and alcohol consumption (Ridout et al., 2012; Stoddard et al., 2012). In addition, the number of Facebook friends one has also appears to be a risk factor for alcohol outcomes, such that individuals with more Facebook friends are more likely to report hazardous drinking (Moreno et al., 2012; Ridout et al., 2012). In contrast, social norms regarding the acceptability of posting alcohol-related content online do not appear related to alcohol behavior (Stoddard et al., 2012). Although it is unlikely that Facebook plays a direct causal role in drinking behavior, alcohol-related Facebook use may be an important outlet and indicator of hazardous drinking and its underlying causes and motivations.

To date, most studies linking Facebook alcohol content and drinking have involved time-intensive direct coding of actual Facebook profiles (Moreno et al., 2012; Ridout et al., 2012), which requires participants’ permission for account access or reliance on a potentially biased population of individuals who maintain public profiles without privacy settings. Even the practice of “friending” participants to gain access does not preclude the use of privacy filters, which restrict access to a user’s Facebook content to specific Facebook friends or groups. This practice can prevent researchers from viewing Facebook activity that a participant considers sensitive or private, which could include alcohol-related postings. Only a single published study has reported use of a self-report measure in assessing alcohol-related Facebook activity (Stoddard et al., 2012), and their alcohol-related outcome variables were confined to alcohol consumption in the past 30 days. The aim of the current study was to further develop a self-report measure of alcohol-related Facebook postings (e.g., status updates, wall posts, comments, or photos related to drinking) and evaluate its relation to multiple aspects of self-reported drinking behavior in a large sample of college students from the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Self-report measures have their own drawbacks regarding participants’ ability and willingness to accurately recall past behavior. However, the self-report format, with further validation, would allow researchers to reach a wider participant base (college student or otherwise) and pose questions about participants’ own behavior as well as their perceptions of their friends’ behavior on Facebook news feeds and other platforms. In short, a self-report measure might allow access to information that is currently not accessible to researchers. Thus, a contribution of the present study is that it allows us to reach more people, acquire difficult-to-obtain information, and access information about both individuals and their Facebook friends.

Alcohol-related postings and drinking motives

Drinking motives are powerful proximal predictors of alcohol consumption and problems (Cox and Klinger, 1998), especially in college students (e.g., Cooper, 1994). Four main drinking motives have been identified as particularly influential for college students: social, conformity, enhancement, and coping motives (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche et al., 2008; Mohr et al., 2005). Social motives are defined as drinking to be sociable and engaging in socialization with others, such as at parties or celebrations, whereas conformity motives refer to drinking to “fit in” or to be liked and included by peers. Enhancement motives are reported by individuals who drink to enhance a positive emotional state, such as drinking because it “feels good” or is “fun,” whereas coping motives refer to drinking to relieve stress or cope with negative emotions.

Social and conformity motives, in particular, have strong social components and may potentially encourage alcohol-related social media use as well as real-life drinking behavior. Facebook is an inherently socially motivated activity and may serve some of the same functions as alcohol among students who are socially motivated to drink. Such students may engage in both greater alcohol consumption and more alcohol-related posting on Facebook as an outlet for gratifying such motives. In this same vein, students who view drinking as normatively desirable may post alcohol-related content on Facebook in an effort to fit in and conform to perceived social norms.

Enhancement and coping motives for drinking may likewise be gratified through alcohol-related social media posting. Facebook may provide a complementary means of coping with negative emotions and problems by serving as a distraction or as a means to seek and receive emotional support. It may also serve as a forum for voicing coping motives, such as posts about “needing” a drink after a stressful day at work. In a similar fashion, enhancement motives are particularly important in the college demographic, who often report drinking to have a good time or because it feels good. To the extent that posting about one’s alcohol use or partying actually enhances the enjoyment of such activities, enhancement motives may also motivate alcohol-related posting on Facebook.

Therefore, all four drinking motives may be associated with heavy alcohol-related Facebook posting, which may satisfy motives in a function similar to actual drinking. The present research extends previous research by evaluating (a) whether social, enhancement, conformity, and coping motives for drinking are associated with increased alcohol-related Facebook use and (b) whether Facebook use is merely a proxy for some or all of those motives or if it actually accounts for unique variance in alcohol-related outcomes above and beyond these motives.

The current study investigated (a) whether self-reported alcohol-related postings on Facebook by an individual or an individual’s Facebook friends are related to common motivations for drinking and (b) whether such postings are uniquely associated with individuals’ self-reported alcohol outcomes (e.g., alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT] scores, and alcohol cravings). We hypothesized that both measures of alcohol content on Facebook would be significantly and positively related to drinking motives and alcohol outcomes. We also hypothesized that self-related alcohol content, because it is a more direct reflection of an individual’s thoughts and actions, would be more strongly related to alcohol outcomes than the alcohol-related postings of an individual’s Facebook friends. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the relationship between increased alcohol-related Facebook posting and alcohol outcomes would continue to be significant even when well-established, powerful predictors of drinking (i.e., drinking motives) were controlled for. We included such motives as covariates to control for the possibility that alcohol-related Facebook use is merely acting as a proxy for these well-established motives. In addition, we also included gender and number of Facebook friends as covariates to control for their established associations with increased alcohol consumption.

Method

Procedure

Procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board. Participants were recruited from a randomized list of approximately 2,500 current, full-time undergraduate students between the ages of 18 and 25 years obtained from the university registrar’s office and invited via email to participate in a study about cognitive processes and alcohol. Forty-four percent of the students contacted agreed to participate in the study. They were provided with a link to a website where volunteers underwent informed consent and completed an online battery of questionnaires as part of a screening process for a larger study. Participants were compensated $15 for completing the online survey.

Participants

Participants consisted of 1,106 undergraduates (449 men, 654 women, 2 transgender, 1 declined to answer) between the ages of 18 and 25 years (M = 20.40, SD = 1.60) at a large university in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Fifty-nine percent of students were identified as White, 27% as Asian, 8% as biracial or multiracial, and the remaining 6% as Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, unknown, or declined to answer. Seven participants were excluded from analyses because they failed screening checks for answering randomly, leaving a final sample of 1,099 participants.

Measures

Facebook alcohol content.

The Facebook Alcohol Questionnaire was developed for this study to assess the degree to which participants post and view alcohol-related content on Facebook. The measure included 10 items. The first item asked participants whether they had a current Facebook account. The next six items asked participants to report how often they post alcohol-related content on Facebook (including status updates, comments, and pictures of themselves or others) and how often their Facebook friends post such alcohol-related content on Facebook. Answer choices ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (daily). An additional item asked participants how many Facebook friends they have. Two items, not used for this study, assessed participants’ number of real-life friends and close friends. Copies of the measure are available on request from the corresponding author.

Drinking motives.

Drinking motives were assessed using the social and coping motive subscales of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (Cooper, 1994). Each subscale consists of five items asking respondents to indicate how often (1 = never to 4 = always) they use alcohol for the social, enhancement, conformity, and coping reasons listed (social motives: α = 93; enhancement motives: α = 91; conformity motives: α = .87; and coping motives: α = .88).

Alcohol consumption.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985) assesses typical weekly alcohol consumption over the past 3 months. Participants are asked to report how many U.S. standard drinks they consumed on each day of a typical week. Scores thus reflect the average number of drinks consumed per week in the past 3 months. Participants were provided with common standard drink equivalencies.

Alcohol problems.

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989) asks participants to report how many times in the past 3 months (from 0 = never to 4 = more than 10 times) they experienced 23 symptoms of problem drinking and negative consequences as a result of drinking, ranging from mild (“Had a bad time”) to serious (“Suddenly found yourself in a place that you could not remember getting to”). Two additional items were added asking participants how often they had driven shortly after consuming two and four drinks, respectively (α = 93).

Alcohol use disorders.

The AUDIT (Babor et al., 2001) is a widely used 10-item clinical measure that can be used to identify individuals at risk for meeting criteria for alcohol use disorders. Participants are asked how much and how often they typically drink on a typical day as well as how often they report cravings and problems because of alcohol. Answer choices range from 0 (never) to 4 (daily or almost daily) (α = 84).

Alcohol cravings.

Because of the new emphasis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), on cravings as a diagnostic criterion for substance use disorders, cravings were assessed as a separate outcome variable. Cravings were measured using the Alcohol Craving Questionnaire Short Form-Revised (ACQ; Singleton et al., 1995). Twelve items measured current alcohol craving (e.g., “If I had some alcohol I would probably drink it”), including alcohol use intentions, anticipated effects of drinking, and lack of control. Responses were measured on a 7-point scale ranging from -3 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). The final item of the ACQ was not administered because of a programming error (α = 80).

Analytic plan

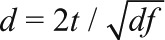

A three-stage analytic plan was used to test the hypotheses of the study. First, because the Facebook Questionnaire was developed for this study, we investigated its underlying structure. We subjected the six items about alcohol-related Facebook postings to principal components analyses and expected to extract two, three-item factors (one about one’s own postings and one about one’s friend’s postings). Second, to examine whether alcohol-related Facebook postings were related to drinking motives and alcohol outcomes, we conducted a series of Pearson r correlations. Finally, to establish whether these postings (self and/or friends) were uniquely related to self-reported alcohol outcomes, a series of regression analyses was conducted—one for each outcome (drinks per week, RAPI scores, AUDIT scores, and cravings). Each of those regression analyses controlled for drinking motives because they are power predictors of drinking. Gender and number of Facebook friends were also controlled for. The model testing cravings used ordinary least squares regression because that variable’s distribution approximated normal. The other three outcomes were not normally distributed; therefore, count regression models with a negative binomial log link (see Atkins and Gallop, 2007) were used. Additional detail regarding the count regression models is provided in the Alcohol-related postings and drinking outcomes section of the Results.

Results

Factor analysis of Facebook Questionnaire

To investigate the underlying structure of the six alcohol-related postings items on the Facebook Questionnaire, principal components analysis with varimax rotation was performed. Two components were extracted having eigenvalues of 2.91 and 1.27, respectively. The first component comprised four items about one’s own behavior (Facebook self; e.g., how often you post alcohol-related status updates/comments or pictures of yourself drinking alcohol and how often your friends post pictures of you drinking alcohol). The second component comprised two items about friends’ behavior (Facebook friend; e.g., how often your friends post pictures of themselves drinking and how frequently they mention alcohol in their status updates). We initially expected three items for each component based on the identity of the person posting the information (e.g., the respondent or the respondent’s friends). However, the sixth item (“How often do your friends post pictures of you drinking?”) loaded more strongly on the component regarding one’s own behavior. In retrospect, this finding was not surprising because the existence of photos of the respondent drinking would necessarily be a direct result of the respondent’s own behavior and, thus, more in keeping with the other self-relevant items. Therefore, that item was retained in the Facebook self component. The two components explained 70% of the variance, with Facebook self explaining 49% and Facebook friend explaining 21%. Rotated factor loadings are shown in Table 1. Cronbach’s α’s were strong for both components (Facebook self: α = .79; Facebook friend: α = .79).

Table 1.

Rotated factor loadings for the Facebook Alcohol Questionnaire

| Questionnaire items | Component 1 Facebook self | Component 2 Facebook friend |

| 1. How often do you post pictures of yourself drinking alcohol on Facebook? | .88 | .05 |

| 2. How often do you post pictures of other people drinking alcohol on Facebook? | .83 | .08 |

| 3. How often do you mention alcohol in your status updates, comments, or wall posts on Facebook? | .66 | .22 |

| 4. How often do your Facebook friends post pictures of themselves drinking alcohol on Facebook? | .21 | .88 |

| 5. How often do your friends post pictures of you drinking alcohol on Facebook? | .71 | .28 |

| 6. How often do your Facebook friends mention alcohol in their status updates, comments, or wall posts on Facebook? | .12 | .90 |

Notes: n = 1,051; N = 1,099; missing data are attributable to skipped items in participants’ responses.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for the sample are shown in Table 2. On average, participants reported consuming six drinks per week on a typical week during the last month and experiencing approximately five alcohol-related consequences over the last 3 months. With respect to behavior on Facebook, participants reported having an average of 438 friends. Facebook self scores were, on average, between “never” and “less than once a month.” Facebook friend scores were higher—on average, between “less than once a month” and “monthly.”

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics for Facebook and alcohol measures (N = 1,099)

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | M | SD |

| 1. Facebook self | – | .36 | .32 | .46 | .47 | .53 | .32 | .38 | .37 | .22 | .31 | 0.39 | 0.51 |

| 2. Facebook friend | – | .26 | .23 | .24 | .29 | .16 | .21 | .20 | .17 | .15 | 1.89 | 1.00 | |

| 3. No. of Facebook friends | – | .34 | .832 | .38 | .13 | .23 | .25 | .14 | .12 | 437.83 | 292.31 | ||

| 4. Drinks | – | .54 | .74 | .37 | .41 | .47 | .20 | .30 | 6.44 | 8.97 | |||

| 5. RAPI score | – | .75 | .51 | .40 | .43 | .30 | .51 | 5.21 | 8.35 | ||||

| 6. AUDIT score | – | .50 | .56 | .58 | .30 | .47 | 6.26 | 5.81 | |||||

| 7. Cravings | – | .49 | .41 | .38 | .61 | -18.07 | 10.55 | ||||||

| 8. Social motives | – | .79 | .52 | .57 | 3.09 | 1.25 | |||||||

| 9. Enhancement motives | – | .41 | .60 | 2.51 | 1.18 | ||||||||

| 10. Conformity motives | – | .50 | 1.71 | 0.81 | |||||||||

| 11. Coping motives | – | 1.80 | 0.90 |

Notes: Facebook self = score on self component (Component 1) of Facebook posting measure (higher = more frequent self-related alcohol posting); Facebook friend = score on friend component (Component 2) of Facebook posting measure (higher = more frequent alcohol posting by Facebook friends); no. of Facebook friends = number of Facebook friends, from the Facebook Alcohol Questionnaire; drinks = no. per week, based on the Daily Drinking Questionnaire; RAPI = total scores on the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (higher = more alcohol-related problems); AUDIT = total scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (higher = greater risk of alcohol use disorder); cravings = from the Alcohol Cravings Questionnaire (higher = greater cravings); social motives = from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (higher = drinking more motivated by social reasons); enhancement motives = from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (higher = drinking more motivated to “enhance” enjoyment or fun); conformity motives = from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (higher = drinking more motivated by social expectations/to conform to norms); coping motives = from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (higher = drinking more motivated by trying to cope with problems). All correlations are significant at p < .001.

To investigate the basic relationships between study variables, Pearson r correlations were conducted. Those correlations are also displayed in Table 2. Facebook self and Facebook friend were moderately correlated with each other (r = .36). Both Facebook self and Facebook friend were positively correlated with drinking motives and drinking outcomes, with the lowest correlation between Facebook friend and coping motives (r = .15) and the highest correlation between Facebook self and AUDIT scores (r = .53).

Alcohol-related postings and drinking outcomes

Finally, we sought to test whether one’s own or one’s friends’ alcohol-related postings accounted for unique variance in alcohol-related outcomes (cravings, drinks per week, RAPI scores, and AUDIT scores). A series of regression models was conducted. For each model, the four drinking motives, participant gender, and number of Facebook friends were entered as control variables. Facebook self and Facebook friend were the main predictors of interest. All predictors were entered simultaneously in the model and were mean-centered to facilitate interpretation. Gender was dummy coded (0 = men, 1 = women).

Two types of regression models were used for this investigation. Ordinary least squares regression was used when investigating alcohol cravings because its distribution approximated normal. Because of nonnormality in the distribution of the other outcomes, count regression models with a negative binomial log link (see Atkins and Gallop, 2007) were used for those outcome variables (e.g., drinks per week, RAPI scores, and AUDIT scores). Count regression models enable one to fit dependent variables with a range of distributions in addition to the normal distribution. A negative binomial model was a better fit for these and provided a good fit for the three outcome variables (i.e., the ratio of deviance to degrees of freedom was close to 1). Please note that other than the fit of the outcome variable (linear vs. negative binomial), each model tested was constructed as described earlier. See Table 3 for regression model statistics.

Table 3.

Alcohol-related Facebook posting as a predictor of drinking outcomes

| Variable | B | SE B | Exp. B | t | Cohen’s d |

| Drinks per week | |||||

| Gender | -0.55 | 0.07 | 0.58 | -8.01*** | 0.49 |

| Social motives | 0.36 | 0.05 | 1.43 | 7.53*** | 0.46 |

| Enhancement motives | 0.29 | 0.05 | 1.34 | 6.18*** | 0.38 |

| Conformity motives | -0.16 | 0.05 | 0.85 | -3.10*** | 0.19 |

| Coping motives | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.10 | 1.96* | 0.12 |

| No. of Facebook friends | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 10.00*** | 0.62 |

| Facebook self | 0.56 | 0.08 | 1.75 | 7.44*** | 0.46 |

| Facebook friend | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.49 | 0.03 |

| RAPI scores | |||||

| Gender | -0.25 | 0.07 | 0.78 | -3.44** | 0.21 |

| Social motives | 0.37 | 0.05 | 1.44 | 7.55*** | 0.46 |

| Enhancement motives | 0.13 | 0.05 | 1.14 | 2.80** | 0.17 |

| Conformity motives | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 | -0.04 | 0.00 |

| Coping motives | 0.46 | 0.05 | 1.58 | 9.18*** | 0.56 |

| No. of Facebook friends | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 10.00*** | 0.61 |

| Facebook self | 0.50 | 0.08 | 1.65 | 6.46*** | 0.40 |

| Facebook friend | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.07 | 1.84† | 0.11 |

| AUDIT scores | |||||

| Gender | -0.32 | 0.04 | 0.73 | .49*** | 0.46 |

| Social motives | 0.28 | 0.03 | 1.33 | 9.59*** | 0.59 |

| Enhancement motives | 0.18 | 0.03 | 1.20 | 6.28*** | 0.39 |

| Conformity motives | -0.09 | 0.03 | 0.91 | -2.91** | 0.18 |

| Coping motives | 0.14 | 0.03 | 1.15 | 4.88*** | 0.30 |

| No. of Facebook friends | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 13.44*** | 0.83 |

| Facebook self | 0.36 | 0.04 | 1.43 | 8.25*** | 0.51 |

| Facebook friend | 0.05 | 0.02 | 1.05 | 2.23* | 0.14 |

| Cravings | |||||

| Gender | -1.60 | 0.50 | -3.20** | 0.20 | |

| Social motives | 0.75 | 0.34 | 2.17* | 0.13 | |

| Enhancement motives | 1.15 | 0.36 | 3.23** | 0.20 | |

| Conformity motives | 0.56 | 0.38 | 1.48 | 0.09 | |

| Coping motives | 5.04 | 0.37 | 13.75*** | 0.84 | |

| No. of Facebook friends | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.42 | 0.03 | |

| Facebook self | 1.96 | 0.56 | 3.48** | 0.21 | |

| Facebook friend | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.82 | 0.05 |

Notes: N = 1,099; all predictors other than gender were grand-mean-centered; gender was dummy coded (0 = men, 1 = women); Cohen’s  ; the regression models used generalized linear models with a negative binomial log link for all outcome variables other than cravings; the regression model for the cravings variable used ordinary least squares regression. No. = number; Facebook self = score on self component (Component 1) of Facebook posting measure; Facebook friend = score on friend-component (Component 2) of Facebook posting measure; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

; the regression models used generalized linear models with a negative binomial log link for all outcome variables other than cravings; the regression model for the cravings variable used ordinary least squares regression. No. = number; Facebook self = score on self component (Component 1) of Facebook posting measure; Facebook friend = score on friend-component (Component 2) of Facebook posting measure; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Drinks per week.

Facebook self, but not Facebook friend, was a unique and positive predictor of drinks per week (p < .001). All control variables also accounted for significant variance in drinks per week (Table 3).

Alcohol-related problems.

Facebook self again positively and uniquely predicted self-reported alcohol-related problems. The effect for Facebook friend was marginally significant (p = .07) in positively predicting alcohol-related problems. Control variables also accounted for significant variance in alcohol-related problems, with the exception of conformity motives.

AUDIT scores.

Both Facebook self and Facebook friend significantly and positively predicted AUDIT scores (ps < .05). Control variables also accounted for significant variance in scores.

Alcohol cravings.

Facebook self, but not Facebook friend, significantly and positively predicted alcohol cravings (p < .001). Of the control variables, only conformity motives and the number of Facebook friends did not predict cravings.

Discussion

Results were generally consistent with expectations. As predicted, alcohol-related content on Facebook, both self- and friend-generated, was linked to all four motives for drinking, suggesting that alcohol-related use of Facebook may be motivated by some of the same factors that drive real-life drinking behavior. In addition, alcohol-related content posted on Facebook, particularly content about one’s self, was significantly associated with real-life drinking behaviors even after drinking motives were controlled for. Frequent posting of self-related alcohol content on Facebook in the form of status updates, comments, and photos was significantly associated with greater self-reported alcohol consumption, more alcohol-related problems, higher scores on a clinical screening measure for risk of alcohol use disorders, and stronger alcohol cravings. Findings related to friends’ postings were mixed. Friends’ postings of alcohol-related status updates, comments, and photos were significantly related to higher scores on a clinical screening measure for risk of alcohol use disorders and marginally related to experiencing more alcohol-related problems. However, contrary to expectations, friends’ postings were not significantly associated with greater alcohol consumption or alcohol cravings. Finally, we replicated previous findings that the number of Facebook friends was significantly related to alcohol outcomes, such that having more Facebook friends was associated with increased likelihood of meeting clinical criteria for risk of alcohol disorders, greater alcohol consumption, and more alcohol-related problems, but not stronger alcohol cravings (Moreno et al., 2012; Ridout et al., 2012). These relationships held true even when known predictors of drinking, including gender and drinking motives, were controlled for.

Theoretical implications

First, by assessing both self and friend alcohol-related Facebook content, we can directly contrast the role that an individual’s own Facebook activity and an individual’s friends’ activities play in shaping an individual’s drinking behaviors. This is important from the standpoint of determining whether Facebook plays merely a self-representational role and/or whether a social influence role might also be possible. Consistent with expectations, self-related alcohol posting appears to be more influential than friends’ behavior when examined cross-sectionally. This suggests that the increased association with hazardous drinking may be the result of accurate self-representation on social media platforms rather than the result of social influence. Future research should address why friends’ activity is predictive of risk for meeting clinical criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence but not actual consumption or cravings.

Examining the relationship between self and friend postings experimentally could help determine whether these relationships hold when investigated in a controlled laboratory setting. The elevated risk of meeting criteria for alcohol-related disorders associated with friends’ frequent posting of alcohol-related content may be primarily because of the potential risks associated with interacting with friends who may themselves be heavy drinkers. In addition, although the present study examines the link between an individual’s Facebook friends and the individual’s own alcohol behavior, the relationship between friends’ social influence and alcohol may be bidirectional. Litt and Stock’s (2011) work in the laboratory suggests that young adolescents may view alcohol use more positively and express more willingness to drink after exposure to alcohol-related Facebook posts made by older peers. In addition, there may be differences between in-person versus online exposure to friends’ alcohol use. Future experimental work should determine whether friends’ postings are more important experimentally and/or more important for some individuals or groups as well as both sides of this potentially bidirectional relationship.

Second, the current study also demonstrates that these relations are found even when well-established predictors of alcohol use are controlled for. Self-related alcohol posts are associated with increased risk of hazardous drinking, even after gender, number of Facebook friends, and common drinking motives are controlled for. Likewise, having friends who frequently make alcohol-related postings is associated with increases in an individual’s risk of meeting clinical criteria for alcohol disorders. This suggests that alcohol-related activity on Facebook is an important predictor of drinking outcomes that accounts for unique variance not captured by other measures. Given the ubiquity of Facebook in the college student demographic, it is important to understand that activity on Facebook has potentially real and serious offline implications. Future research should identify and address the factors that make alcohol-related activity on Facebook uniquely predictive of alcohol outcomes.

Third, the present research reveals that posting alcohol-related content on Facebook is correlated with social, coping, conformity, and enhancement drinking motives. This pattern of findings suggests that such postings may potentially be driven by some of the same motives that predict actual drinking and/or by common factors that underlie drinking motives. This supposition, although consistent with study findings, is speculative because of the cross-sectional nature of the study. As such, specific types of alcohol-related postings may reflect and express specific types of underlying drinking motivations. For example, just as socially motivated drinking may be expressed by partying with friends, a socially motivated post about alcohol might display a picture of friends drinking at a party, whereas a coping-motivated post about alcohol might express the desire to have a few drinks after a really hard day at work. Additional research that integrates self-report measures of Facebook postings with coding of actual posts may further clarify how underlying drinking motivations are expressed through different classifications of alcohol-related Facebook postings and potentially test for moderating or mediating effects of drinking motives on Facebook use.

Clinical implications

Understanding the role of social media in college student drinking behaviors is also important from an applied perspective in identifying individuals at risk and facilitating prevention and intervention efforts. Facebook is both a social media platform and a powerful advertising tool capable of delivering targeted ad content based on users’ profiles and posting activity. If the presence of alcohol-related content on Facebook is indicative of real-life hazardous drinking, then targeting those individuals could be done discreetly and anonymously through an automated process and prevention/intervention materials delivered directly to individuals through Facebook itself. Identification of at-risk drinkers through Facebook may also facilitate delivery of offline intervention efforts. In addition, students who post alcohol-related content on Facebook or who have friends who do so may also be more likely to receive advertising from alcohol manufacturers. Facebook allows alcohol beverage manufacturers to advertise to individuals older than 21 in the United States with some content restrictions (Facebook Advertising Guidelines, 2012; Facebook Help Center: Ads & Sponsored Stories Alcohol, n.d.). Companies can choose to direct ads based on user interest in alcohol (determined by the user’s page “Likes,” apps, and information added to their timeline) as well as their connections to their Facebook friends (Facebook Help Center: Ads & Sponsored Stories Targeting Options, n.d.). Thus, if one Facebook user “likes” Budweiser’s Facebook page, Budweiser can then choose to target that user’s Facebook friends to receive additional advertising. Therefore, individuals older than 21 who post alcohol-related activity on Facebook may increase their own chances as well as their Facebook friends’ chances of receiving targeted alcohol advertising.

Furthermore, although other studies have examined the effect of Facebook activity on alcohol use, this study is the first to examine alcohol cravings as a distinct outcome variable. This may be especially timely as cravings was added to the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Methodological implications

To date, the majority of published studies of alcohol-related content on Facebook (Moreno et al., 2012; Ridout et al., 2012) have involved direct coding of actual Facebook profiles. Measures such as the one developed for this study may facilitate research on Facebook and other social networking sites as well as assist in identifying potential at-risk individuals who are posting or viewing alcohol-related content. Self-report measures save time and incorporate a broader and larger participant base by reducing participant and researcher burden and circumventing Facebook’s built-in privacy filters. Additionally, individuals who may be reluctant to report hazardous drinking may be more tolerant of answering questions about their Facebook usage. The study’s findings provide initial validation of this approach, but additional validation is important. For example, future research should attempt to include coding of individuals’ Facebook profiles to provide confirmation that self-reports about alcohol-related Facebook content correspond with posting behavior. It is encouraging, however, that findings using this self-report measure are consistent with previous studies that relied on researchers coding actual Facebook profiles (e.g., Moreno et al., 2012; Ridout et al., 2012)—that is, using both methods, alcohol-related content on Facebook predicted actual alcohol consumption, problems related to alcohol, and clinical thresholds for alcohol disorders.

Limitations and conclusion

Although the current study offers a helpful first step in establishing a link between alcohol-related social media use and actual alcohol behavior, study implications are constrained by several important limitations. The current study presumes that alcohol-related Facebook use may be an expression of drinking motives and risk factors and an indicator (but not a direct cause) of real-life drinking behavior, but a causal influence cannot be either excluded or confirmed because of the cross-sectional nature of the study. In addition, it is difficult to disentangle the role of in-person versus online peer influence. Measures of offline exposure to friends’ drinking behavior could help clarify what aspects of friends’ influence via social media are unique to the online environment. Additional limitations include the use of a single sample of university students and a reliance on self-reported measures of drinking. Although self-report measures such as the AUDIT, Daily Drinking Questionnaire, and RAPI are well-validated measures of alcohol use, they are not immune to the limitations of self-report measures. Future research involving in vivo alcohol administration or other methods may be useful in confirming that the increase in self-reported drinking associated with higher levels of alcohol-related Facebook posting is, in fact, indicative of real-world drinking. Special care should be taken when using in vivo alcohol administration in this population because frequent posters of online alcohol-related content may be at an elevated risk for alcohol-related problems.

Despite these limitations, this study represents an important step to understanding the role of social media in drinking behaviors and in facilitating research toward this goal. Posting alcohol-related content on social media platforms such as Facebook is associated with common motivations for drinking and is, in itself, a strong predictive indicator of drinking outcomes independent of drinking motives. This is particularly the case for self-related alcohol postings, which were stronger predictors of drinking behavior than the alcohol-related Facebook activity of one’s friends. With additional validation, this measure could serve to identify individuals at risk for hazardous drinking. Furthermore, social media platforms such as Facebook could also represent an additional means for delivering prevention or interventions.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant R00AA017669. Manuscript support was also provided by Grant R01AA021763. NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the article; or the decision to submit this article for publication.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol references on undergraduate males’ Facebook profiles. American Journal of Men s Health. 2011;5:413–420. doi: 10.1177/1557988310394341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facebook Advertising Guidelines. 2012. Retrieved from https://www. facebook. com/ad_guidelines.php.

- Facebook Help Center Ads & Sponsored Stories Alcohol. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/help/1 10094445754628/

- Facebook Help Center Ads & Sponsored Stories Targeting Options. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/help/131834970288134/

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2010. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19-50. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, von Fischer M, Gmel G. Personality factors and alcohol use: A mediator analysis of drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45:796–800. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Pew Research Internet Project: Social media and young adults. 2010, February 3. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx.

- Litt DM, Stock ML. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: The roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:708–713. doi: 10.1037/a0024226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, Carney MA. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, Walker L, Christakis DA. Real use or “real cool”: Adolescents speak out about displayed alcohol references on social networking websites. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:420–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Christakis DA, Egan KG, Brockman LN, Becker T. Associations between displayed alcohol references on Facebook and problem drinking among college students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166:157–163. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EM, Snelson C, Elison-Bowers P. Image and video disclosure of substance use on social media websites. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26:1405–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout B, Campbell A, Ellis L. ‘Off your Face(book)’: Alcohol in online social identity construction and its relation to problem drinking in university students. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2012;31:20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton EG, Tiffany ST, Henningfield JE. Problems of Drug Dependence, 1994: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting, the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc., Volume II: Abstracts. NIDA Research Monograph 153 (p. 289) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1995. Development and validation of a new questionnaire to assess craving for alcohol. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Bauermeister JA, Gordon-Messer D, Johns M, Zimmerman MA. Permissive norms and young adults’ alcohol and marijuana use: The role of online communities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:968–975. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosun LP. Motives for Facebook use and expressing “true self” on the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28:1510–1517. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC, Brown BB. Motives for using Facebook, patterns of Facebook activities, and late adolescents’ social adjustment to college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:403–416. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9836-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]