Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the major stem cells for cell therapy, have been used in the clinic for approximately 10 years. From animal models to clinical trials, MSCs have afforded promise in the treatment of numerous diseases, mainly tissue injury and immune disorders. In this review, we summarize the recent opinions on methods, timing and cell sources for MSC administration in clinical applications, and provide an overview of mechanisms that are significant in MSC-mediated therapies. Although MSCs for cell therapy have been shown to be safe and effective, there are still challenges that need to be tackled before their wide application in the clinic.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cell, cell therapy, tissue injury, degenerative disease, immune disorder, graft-versus-host disease, immunomodulation, trophic factor

Introduction

Stem cells are unspecialized cells with the ability to renew themselves for long periods without significant changes in their general properties. They can differentiate into various specialized cell types under certain physiological or experimental conditions. Cell therapy is a sub-type of regenerative medicine. Cell therapy based on stem cells describes the process of introducing stem cells into tissue to treat a disease with or without the addition of gene therapy. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have been widely used for allogeneic cell therapy. The successful isolation of pluripotent embryonic stem (ES) cells from the inner cell mass of early embryos has provided a powerful tool for biological research. ES cells can give rise to almost all cell lineages and are the most promising cells for regenerative medicine. The ethical issues related to their isolation have promoted the development of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which share many properties with ES cells without ethical concerns. However, one key property of ES cells and iPS cells that may seriously compromise their utility is their potential for teratoma formation.

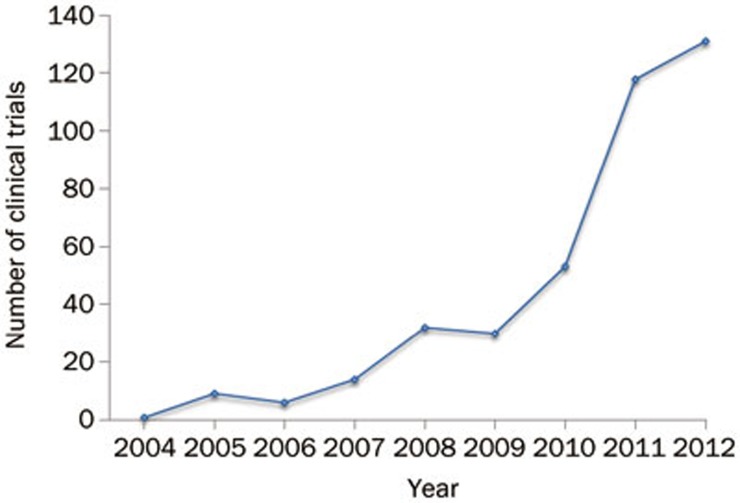

Due to the limitation of using ES and iPS cells in the clinic, great interest has developed in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are free of both ethical concerns and teratoma formation. These cells were first isolated and characterized by Friedenstein and his colleagues in 1974. MSCs, also called mesenchymal stromal cells, are a subset of non-hematopoietic adult stem cells that originate from the mesoderm. They possess self-renewal ability and multilineage differentiation into not only mesoderm lineages, such as chondrocytes, osteocytes and adipocytes, but also ectodermic cells and endodermic cells1,2,3,4,5. MSCs exist in almost all tissues. They can be easily isolated from the bone marrow, adipose tissue, the umbilical cord, fetal liver, muscle, and lung and can be successfully expanded in vitro6,7,8,9,10. The number of clinical trials on MSCs has been rising since 2004 (Figure 1). Although the “gold rush” to use MSCs in clinical settings began with high enthusiasm in many countries, with China, Europe and US leading the way (http://clinicaltrial.cn), numerous scientific issues remain to be resolved before the establishment of clinical standards and governmental regulations.

Figure 1.

Number of registered clinical trials of mesenchymal stem cells-based therapy on ClinicalTrials.gov.

What can MSCs do?

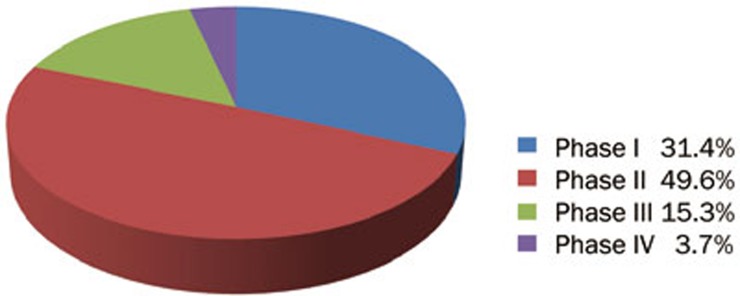

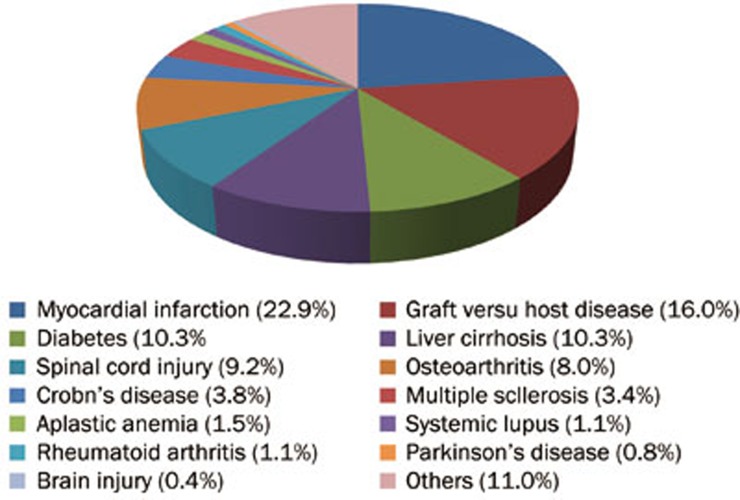

Currently, there are 344 registered clinical trials in different clinical trial phases (Figure 2) aimed at evaluating the potential of MSC-based cell therapy worldwide. With the advancement of preclinical studies, MSCs have been shown to be effective in the treatment of many diseases, including both immune diseases and non-immune diseases (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Clinical phages of mesenchymal stem cells-based therapy. Data from ClinicalTrials.gov.

Figure 3.

Percentages of the common diseases now treated with mesenchymal stem cells. Data from ClinicalTrials.gov.

MSCs in tissue repair

The wide tissue distribution and multipotent differentiation of MSCs together with the observed reparative effects of infused MSCs in many clinical and preclinical models11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 strongly suggest a critical role of MSCs in injury healing. They are believed to be responsible for growth, wound healing, and replacing cells that are lost through daily wear and tear and pathological conditions. Because of these functions, they have been shown to be effective in the treatment of tissue injury and degenerative diseases. In the digestive system, autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) improved the clinical indices of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients and liver failure patients caused by hepatitis B27,28. BM-MSCs can also exert strong therapeutic effects in the musculoskeletal system. They have been shown to be effective in the regeneration of periodontal tissue defects, diabetic critical limb ischemia, bone damage caused by osteonecrosis and burn-induced skin defects29,30,31. In preclinical studies, investigations by the Prockop team have also shown that human MSCs are effective in treating myocardial infarction32 and cornea damage33 through the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 protein (TSG-6), which reduces inflammation and promotes tissue reconstruction. A similar phenomenon has been reported for MSCs in treating other tissue injuries, such as the brain, spinal cord34 and lung35,36, all target organs of MSCs in the future. Additionally, co-transplantation of MSCs can enhance the effect of HSCs in treating radiation victims37.

MSCs in immune disorder therapy

In addition to their property of treating tissue injury, MSCs are also applied to alleviate immune disorders because MSCs have a powerful capacity of regulating immune responses. Various studies have evaluated the therapeutic effect of MSCs in preclinical animal models and demonstrated great clinical potential. For example, MSCs have been successfully applied to reverse graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) in patients receiving bone marrow transplantation38,39, especially in patients diagnosed with severe steroid resistance40,41,42. Similarly, in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Crohn's disease patients, both autologous and allogeneic MSCs were able to suppress inflammation and reduce damage to the kidneys and bowel through the possible induction of regulatory T cells in patients43,44,45,46. It also has been reported that BM-MSCs can improve multiple system atrophy (MSA)47, multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)48,49,50, and stroke, likely through immediate immunomodulatory effects51. Osiris' Prochymal, the world's first stem cell drug approved in Canada on May 12, 2012, was successful in phase III clinical trials in treating GvHD and Crohn's disease and has become the only stem cell-based drug approved by FDA40,52.

Methods and techniques of applying MSCs in the clinic

Engraftment of MSCs

In all of the preclinical and clinical studies, the engraftment of MSCs into damaged tissues via migration to enhance tissue repair/regeneration is a crucial process for clinical efficacy, regardless of the type of organ or specific disease. As more and more clinical studies are performed, the engraftment properties of MSCs are gradually being evaluated in many models and clinical trials. In 2000, a study of human MSC in utero transplantation in sheep demonstrated long-term engraftment as long as 13 months after transplantation, even when cells were transplanted after the expected development of immunocompetence, and the transplanted human MSCs could undergo site-specific differentiation into chondrocytes, adipocytes, myocytes and cardiomyocytes, bone marrow stromal cells and thymic stroma53. However, the overwhelming majority of MSCs were found in the lung after systemic administration in normal recipients, and these MSCs disappeared gradually over time54. The mechanisms of these phenomena are still unclear.

The site of delivery most likely affects the trafficking of MSCs to target organs. Generally, two approaches of systemic administration have been used for MSC applications. One is intravenous injection, such as peripheral vein injection (tail vein in mice), utilizing the capabilities of MSCs to migrate to specific inflammatory tissues in vivo, including the cartilage, liver, and lung55,56. Engraftment was demonstrated in animal models and was capable of persisting for as long as 13 months after transplantation53. The other approach is local intraarterial injection, which can enhance the accumulation and increase the dose of MSCs in injured tissues. In a phase I study of MSCs as a treatment for liver cirrhosis in 2007, patients were injected with human MSCs through liver arteries57. Moreover, to increase the number of MSCs and the efficiency of differentiation at the damaged sites, studies on liver cirrhosis, osteonecrosis, skin defects, and spinal cord injury employed local injections instead of the systemic administration of MSCs31. However, which route of administration is best for a particular disease and the possible contraindication of such clinical usage are still unknown.

Time of MSC administration

In addition to the different methods of administration, the timing of delivery and number of cells delivered are also very important. Sudres et al found in their study that MSCs failed to prevent GvHD in mice, and the failure was not due to MSC rejection58. Meanwhile, our finding showed that MSCs could prolong survival in a GvHD mouse model59. One difference between these two studies was the infusion time of MSCs60. Sudres et al injected MSCs 10–15 min before GvHD induction, whereas we injected MSCs 3 d and 7 d after bone marrow transplantation. It is possible that the time of MSC administration is important for the therapeutic effect. Based on the above discussion that the immunosuppressive ability of MSCs must be induced by inflammatory cytokines, it is conceivable that MSC administration at the peak of inflammation may improve the treatment effect. However, this hypothesis needs to be further tested.

Cell sources of MSCs

MSCs exist in almost all tissues. They can be easily isolated from the bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, fetal liver, muscle, and lung and can be successfully expanded in vitro6,7,8,9,10. Although the major source of MSCs in clinic trials is umbilical cord, recent studies have suggested that the allogenicity of MSCs have no significant adverse impact on the engraftment of MSCs in wound healing61. It is better to use freshly isolated MSCs because it has been shown that 5 major histocompatibility complex (MHC II) molecules could be increased during in vitro expansion62,63.

Therapeutic mechanisms of MSCs

As mentioned above, MSCs have displayed great potential in treating a large number of immune and non-immune diseases. However, there are still major questions concerning the optimal dosage of MSCs, routes of administration, best engraftment time and the fate of the cells after infusion64. Thus, it is critical to explore the mechanisms governing MSC-based therapies. Although a uniform mechanism has not yet been discovered, the available data have revealed several working models for the beneficial effects of MSCs. Based on the current understanding, we summarize some key mechanisms that are significant in MSC-mediated therapies. It is noteworthy that for a given disease, multiple mechanisms are likely to contribute coordinately to the therapeutic effect of MSCs.

Homing efficiency

MSCs have a tendency to home to damaged tissue sites. When MSCs are delivered exogenously and systemically administered to humans and animals, they are always found to migrate specifically to damaged tissue sites with inflammation65,66, although many of the intravenously administered MSCs are trapped in the lung67,68. The inflammation-directed MSC homing has been demonstrated to involve several important cell trafficking-related molecules: chemokines, adhesion molecules, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Among these chemokines, the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12- chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2- chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 axes are most studied69,70. Accordingly, CXCR4 was transduced into MSCs to improve their in vivo engraftment and therapeutic efficacy in a rat myocardial infarction model71. The adhesion molecule P-selectin and the VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion protein 1)-VLA-4 (very late antigen-4) interaction has been shown to be key mediators in MSC rolling and firm adherence to endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo72. Interestingly, in a recent report, VCAM-1 antibody-coated MSCs exhibited a higher efficiency of engraftment into inflamed mesenteric lymph nodes and the colon than uncoated MSCs in a mouse inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) model73, suggesting that modulations of the homing property of MSCs could be a viable approach in enhancing their therapeutic effectiveness. In addition to chemokines and adhesion molecules, several MMPs, such as MMP-2 and membrane type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP), have been shown to be essential in the invasiveness of MSCs74,75. It is worth noting that all the homing-related molecules can be up-regulated by inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IL-176,77. Therefore, different inflammation statuses (ie, different levels of inflammatory cytokines) might lead to distinct MSC engraftment and therapeutic efficiencies.

Tumors can be regarded as wounds that never heal and continuously generate various inflammatory cytokines78. Indeed, MSCs that are either de novo mobilized or exogenously administered have been found to migrate to tumors and adjacent tissue sites79. In view of this property, approaches have been developed to engineer several tumor-killing agents, such as IFNα, IFNβ, IL-12, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), in MSCs for tumor-targeted therapy in animal models80,81,82,83,84. More recently, MSCs have also been undergoing development as vehicles for the delivery of nanoparticles to enhance their tumoricidal effects85,86. Further investigations in this direction may lead to novel therapeutic strategies for cancer.

Differentiation potential and tissue engineering

As typical multipotent stem cells, MSCs have been shown to possess the capability to differentiate into a variety of cell types, including adipocytes, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, myoblasts and neuron-like cells. Although it is currently believed that the therapeutic benefits of MSCs are due to more complicated mechanisms, they have been indicated to be able to differentiate into osteoblasts, cardiomyocytes and other tissue-specific cells after their in vivo systemic infusion in the treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta and myocardial infarction in both animals and humans53,87,88.

In addition to systemic delivery, MSCs can be delivered together with various natural and synthetic biomaterial scaffolds. Either undifferentiated or differentiated MSCs can be loaded onto scaffolds before their implantation into damaged tissue sites89,90. Such technologies have been successfully applied in cartilage repair and long bone repair, with the generation of well-integrated and functional hard tissues91,92. The advantage of a tissue-engineered MSC delivery system lies in the ease of controlling and manipulating the implanted cells and tissues, with reduced side effects impacting other organs and tissues. Current improvements in delivery vehicles and compatibility between the scaffolds and MSCs will help to develop a mature technology for clinical applications.

Production of trophic factors

Accumulating evidence has revealed that the therapeutic benefits of MSCs are largely dependent on their capacity to act as a trophic factor pool. After MSCs home to damaged tissue sites for repair, they interact closely with local stimuli, such as inflammatory cytokines, ligands of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and hypoxia, which can stimulate MSCs to produce a large amount of growth factors that perform multiple functions for tissue regeneration93,94,95. Many of these factors are critical mediators in angiogenesis and the prevention of cell apoptosis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), basic fibroblast growth factors (bFGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), IL-6 and CCL-294,96,97. Interestingly, a recent study found that the therapeutic effect of neuronal progenitors on EAE was solely dependent on leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), revealing a similar trophic function as other tissue progenitors/stem cells98. Moreover, many reports have demonstrated that pre-treatment with growth factors or gene modification of MSCs can enhance the therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction and other wound-healing processes99,100. A further understanding of the molecular pathways involved in growth factor production will be helpful to develop better strategies for MSC-based therapies.

Immunomodulation

In the last few years, MSCs have been shown to be effective in treating various immune disorders in human and animal models. In both in vitro and in vivo studies, MSCs have been shown to suppress the excessive immune responses of T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells101,102. The underlying mechanisms are believed to be a combined effect of many immunosuppressive mediators. A majority of the mediators are inducible by inflammatory stimuli, such as nitric oxide (NO), indoleamine 2,3, dioxygenase (IDO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 protein (TSG6), CCL-2, and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1)68,103,104,105,106,107,108. These factors are minimally expressed in unactivated MSCs unless they are stimulated by several inflammatory cytokines, such as IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-178,103. The neutralization of either immunosuppressive effectors or inflammatory cytokines could reverse MSC-mediated immunosuppression79. The concept of inflammation-licensed immunosuppression favors a more rational design for the clinical use of MSCs. First, an optimal administration time point should be carefully selected according to the levels and ratios of different cytokines in the body during disease progression. Previous reports have demonstrated that MSC administration after disease onset may be better than at the same time of disease induction in a mouse GvHD model71,79. Second, cytokine priming should be attempted to improve the therapeutic effect of MSCs. Cheng et al reported that IFNγ-pretreated MSCs protected 100% of mice from GvHD-induced death71. Third, the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs most likely depends on the nature of different diseases due to the distinct inflammatory environments. Even for a specific disease, the diversity of microenvironments in different tissues may also produce different curative effects of MSCs. Therefore, the precise in vivo mechanism of MSCs may be more complex than observed in vitro. Further defining such mechanisms will help to develop better strategies for the clinical use of MSCs.

Unsolved problems and challenges

Although significant progress has been made in stem cell research in recent years, cell therapy with stem cells is far from a mature clinical technology. Because they are free of ethical concerns and have numerous sources, low immunogenicity and no teratoma risk, MSCs are the most commonly used stem cells in current clinical applications. However, there are still several major hurdles to their widespread utility. Further research is needed on interactions between MSCs and the inflammatory milieu in which they reside and the therapeutic mechanisms of MSCs. Furthermore, it is still not known which source should be used for which disease, which route of administration is best suited for a particular disease, and possible contraindications to their clinical use. Once administered, the parameters for monitoring clinical effectiveness also need to be established and are likely to vary for different disorders. Most importantly, established standards for cell expansion protocols, product quality, and safety controls are not available in most countries. Government regulatory agencies are eagerly waiting for detailed answers to these questions to establish regulatory polices to meet the challenges of this newly emerging and rapidly advancing field and benefit patients suffering a wide array of diseases. We look forward to using soluble products of MSCs instead of MSCs themselves in the future, which may simplify the administration of cells and make it safer.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Key Basic Research Project of China (Grant No 2011CB966200, 2010CB945600, and 2011CB965100); Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 81030041); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 31171321 and 81101622); Special Funds for the National Key Sci-Tech Special Project of China (Grant No 2012ZX10002-016 and 2012ZX10002011-011); the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (Grant No 11ZR1449500 and 12ZR1439800); and the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups, NSFC, China (Grant No 81221061).

References

- Bianchi G, Borgonovo G, Pistoia V, Raffaghello L. Immunosuppressive cells and tumour microenvironment: focus on mesenchymal stem cells and myeloid derived suppressor cells. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:941–51. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–4. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granero-Molto F, Weis JA, Longobardi L, Spagnoli A. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine: application to bone and cartilage repair. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:255–68. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem HK, Thiemermann C. Mesenchymal stromal cells: current understanding and clinical status. Stem Cells. 2010;28:585–96. doi: 10.1002/stem.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezawa M, Ishikawa H, Itokazu Y, Yoshihara T, Hoshino M, Takeda S, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells generate muscle cells and repair muscle degeneration. Science. 2005;309:314–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1110364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P, Robey PG, Simmons PJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjos-Afonso F, Bonnet D. Nonhematopoietic/endothelial SSEA-1+ cells define the most primitive progenitors in the adult murine bone marrow mesenchymal compartment. Blood. 2007;109:1298–306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In't Anker PS, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, de Groot-Swings GM, Claas FH, Fibbe WE, et al. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells of fetal or maternal origin from human placenta. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1338–45. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211–28. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzaribachev N, Vaegler M, Schaefer J, Reize P, Rudert M, Handgretinger R, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells: a novel treatment option for steroid-induced avascular osteonecrosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:232–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SM, Hoyland JA. Stem cell regeneration of degenerated intervertebral discs: current status. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12:83–8. doi: 10.1007/s11916-008-0016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amado LC, Saliaris AP, Schuleri KH, St John M, Xie JS, Cattaneo S, et al. Cardiac repair with intramyocardial injection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504388102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Fang X, Gupta N, Serikov V, Matthay MA. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of E. coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in the ex vivo perfused human lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16357–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907996106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekkadan B, van Poll D, Suganuma K, Carter EA, Berthiaume F, Tilles AW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules reverse fulminant hepatic failure. PLoS One. 2007;2:e941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togel F, Hu Z, Weiss K, Isaac J, Lange C, Westenfelder C. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F31–42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Song EC, Kim SJ, et al. Systemic transplantation of human adipose stem cells attenuated cerebral inflammation and degeneration in a hemorrhagic stroke model. Brain Res. 2007;1183:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y, Iriyama A, Ueno S, Takahashi H, Kondo M, Tamaki Y, et al. Subretinal transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells delays retinal degeneration in the RCS rat model of retinal degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tredget EE, Wu PY, Wu Y. Paracrine factors of mesenchymal stem cells recruit macrophages and endothelial lineage cells and enhance wound healing. PLoS One. e1886. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Nishida T, Ishii S, Iijima H, et al. Topical implantation of mesenchymal stem cells has beneficial effects on healing of experimental colitis in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:523–31. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, Benvenuto F, Bonanni I, Gerdoni E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood. 2005;106:1755–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, Koo WW, Gordon PL, Neel M, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 1999;5:309–13. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Herreros D, Pascual I, Peiro C, Rodriguez-Montes JA. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn's fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1416–23. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Gotherstrom C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noth U, Steinert AF, Tuan RS. Technology insight: adult mesenchymal stem cells for osteoarthritis therapy. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:371–80. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erokhin VV, Vasil'eva IA, Konopliannikov AG, Chukanov VI, Tsyb AF, Bagdasarian TR, et al. Systemic transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stem cells of the bone marrow in the treatment of patients with multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Probl Tuberk Bolezn Legk. 2008;(10):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Xie DY, Lin BL, Liu J, Zhu HP, Xie C, et al. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in liver failure patients caused by hepatitis B: short-term and long-term outcomes. Hepatology. 2011;54:820–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.24434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharaziha P, Hellstrom PM, Noorinayer B, Farzaneh F, Aghajani K, Jafari F, et al. Improvement of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients after autologous mesenchymal stem cell injection: a phase I–II clinical trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1199–205. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832a1f6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Chen B, Liang Z, Deng W, Jiang Y, Li S, et al. Comparison of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells for treatment of diabetic critical limb ischemia and foot ulcer: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Ueda M, Hibi H, Baba S. A novel approach to periodontal tissue regeneration with mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma using tissue engineering technology: a clinical case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26:363–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasulov MF, Vasilchenkov AV, Onishchenko NA, Krasheninnikov ME, Kravchenko VI, Gorshenin TL, et al. First experience of the use bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of a patient with deep skin burns. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2005;139:141–4. doi: 10.1007/s10517-005-0232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy GW, Oh JY, Lee RH, Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo J, Coble K, et al. Action at a distance: systemically administered adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs) reduce inflammatory damage to the cornea without engraftment and primarily by secretion of TSG-6. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1572–9. doi: 10.1002/stem.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Zeng YS, Ma YH, Lu LY, Du BL, Zhang W, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a three dimensional gelatin sponge scaffold attenuate inflammation, promote angiogenesis and reduce cavity formation in experimental spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:1881–99. doi: 10.3727/096368911X566181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, Pandey AC, Torres G, Go K, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin M, Sueblinvong V, Eisenhauer P, Ziats NP, LeClair L, Poynter ME, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit Th2–mediated allergic airways inflammation in mice. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1137–48. doi: 10.1002/stem.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapel A, Bertho JM, Bensidhoum M, Fouillard L, Young RG, Frick J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells home to injured tissues when co-infused with hematopoietic cells to treat a radiation-induced multi-organ failure syndrome. J Gene Med. 2003;5:1028–38. doi: 10.1002/jgm.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller I, Kordowich S, Holzwarth C, Isensee G, Lang P, Neunhoeffer F, et al. Application of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in pediatric patients following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008;40:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad VK, Lucas KG, Kleiner GI, Talano JA, Jacobsohn D, Broadwater G, et al. Efficacy and safety of ex vivo cultured adult human mesenchymal stem cells (Prochymal) in pediatric patients with severe refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in a compassionate use study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebriaei P, Isola L, Bahceci E, Holland K, Rowley S, McGuirk J, et al. Adult human mesenchymal stem cells added to corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:804–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KH, Chan CK, Tsai C, Chang YH, Sieber M, Chiu TH, et al. Effective treatment of severe steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease with umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Transplantation. 2011;91:1412–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821aba18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, Locatelli F, Roelofs H, Lewis I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wang D, Liang J, Zhang H, Feng X, Wang H, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2467–75. doi: 10.1002/art.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion F, Nova E, Ruiz C, Diaz F, Inostroza C, Rojo D, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell treatment increased T regulatory cells with no effect on disease activity in two systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2010;19:317–22. doi: 10.1177/0961203309348983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, Maccario R, Avanzini MA, Ubezio C, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut. 2011;60:788–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.214841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijvestein M, Vos AC, Roelofs H, Wildenberg ME, Wendrich BB, Verspaget HW, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell treatment for refractory luminal Crohn's disease: results of a phase I study. Gut. 2010;59:1662–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.215152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, Kim JW, Bang OY, Ahn YH, Joo IS, Huh K. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell therapy delays the progression of neurological deficits in patients with multiple system atrophy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:723–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karussis D, Karageorgiou C, Vaknin-Dembinsky A, Gowda-Kurkalli B, Gomori JM, Kassis I, et al. Safety and immunological effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1187–94. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connick P, Kolappan M, Patani R, Scott MA, Crawley C, He XL, et al. The mesenchymal stem cells in multiple sclerosis (MSCIMS) trial protocol and baseline cohort characteristics: an open-label pre-test: post-test study with blinded outcome assessments. Trials. 2011;12:62. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi MR, Kim HY, Park JY, Lee TY, Baik CS, Chai YG, et al. Selection of optimal passage of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for stem cell therapy in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci Lett. 2010;472:94–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honmou O, Houkin K, Matsunaga T, Niitsu Y, Ishiai S, Onodera R, et al. Intravenous administration of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in stroke. Brain. 2011;134:1790–807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannon PJ. Remestemcel-L: human mesenchymal stem cells as an emerging therapy for Crohn's disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:1249–56. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.602967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechty KW, MacKenzie TC, Shaaban AF, Radu A, Moseley AM, Deans R, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat Med. 2000;6:1282–6. doi: 10.1038/81395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lama VN, Smith L, Badri L, Flint A, Andrei AC, Murray S, et al. Evidence for tissue–resident mesenchymal stem cells in human adult lung from studies of transplanted allografts. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:989–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI29713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaida I, Terai S, Yamamoto N, Aoyama K, Ishikawa T, Nishina H, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow cells reduces CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1304–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang Z, Lu D, Lu M, et al. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2001;32:1005–11. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadnejad M, Namiri M, Bagheri M, Hashemi SM, Ghanaati H, Zare Mehrjardi N, et al. Phase 1 human trial of autologous bone marrow-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3359–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i24.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudres M, Norol F, Trenado A, Gregoire S, Charlotte F, Levacher B, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro but fail to prevent graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:7761–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, Xu G, Zhang Y, Roberts AI, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Hu G, Su J, Li W, Chen Q, Shou P, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression and tissue repair. Cell Res. 2010;20:510–8. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tredget EE, Liu C, Wu Y. Analysis of allogenicity of mesenchymal stem cells in engraftment and wound healing in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarte K, Gaillard J, Lataillade JJ, Fouillard L, Becker M, Mossafa H, et al. Clinical-grade production of human mesenchymal stromal cells: occurrence of aneuploidy without transformation. Blood. 2010;115:1549–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocelli-Tyndall C, Zajac P, Di Maggio N, Trella E, Benvenuto F, Iezzi G, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 and platelet-derived growth factor, but not platelet lysate, induce proliferation-dependent, functional class II major histocompatibility complex antigen in human mesenchymal stem cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3815–25. doi: 10.1002/art.27736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:206–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Gordon PL, Koo WK, Marx JC, Neel MD, McNall RY, et al. Isolated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells engraft and stimulate growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: Implications for cell therapy of bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132252399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A, Lu D, Lu M, Chopp M. Treatment of traumatic brain injury in adult rats with intravenous administration of human bone marrow stromal cells. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:697–702. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000079333.61863.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash IM, Chouraqui P, Baron J, Feinberg MS, Etzion S, Tessone A, et al. Systemic delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted myocardium: feasibility, cell migration, and body distribution. Circulation. 2003;108:863–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084828.50310.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn RF, Hart CA, Corradi-Perini C, O'Neill L, Evans CA, Wraith JE, et al. A small proportion of mesenchymal stem cells strongly expresses functionally active CXCR4 receptor capable of promoting migration to bone marrow. Blood. 2004;104:2643–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belema-Bedada F, Uchida S, Martire A, Kostin S, Braun T. Efficient homing of multipotent adult mesenchymal stem cells depends on FROUNT-mediated clustering of CCR2. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:566–75. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Ou L, Zhou X, Li F, Jia X, Zhang Y, et al. Targeted migration of mesenchymal stem cells modified with CXCR4 gene to infarcted myocardium improves cardiac performance. Mol Ther. 2008;16:571–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruster B, Gottig S, Ludwig RJ, Bistrian R, Muller S, Seifried E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells display coordinated rolling and adhesion behavior on endothelial cells. Blood. 2006;108:3938–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko IK, Kim BG, Awadallah A, Mikulan J, Lin P, Letterio JJ, et al. Targeting improves MSC treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1365–72. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries C, Egea V, Karow M, Kolb H, Jochum M, Neth P. MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and TIMP-2 are essential for the invasive capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells: differential regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 2007;109:4055–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Xu D, Feng G, Bushell A, Muschel RJ, Wood KJ. Mesenchymal stem cells prevent the rejection of fully allogenic islet grafts by the immunosuppressive activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9. Diabetes. 2009;58:1797–806. doi: 10.2337/db09-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Li J, Liao L, Chen B, Li B, Chen L, et al. Regulation of CXCR4 expression in human mesenchymal stem cells by cytokine treatment: role in homing efficiency in NOD/SCID mice. Haematologica. 2007;92:897–904. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang J, L'Huillier A, Ling W, et al. Inflammatory cytokine-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in mesenchymal stem cells are critical for immunosuppression. J Immunol. 2010;184:2321–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaeth E, Klopp A, Dembinski J, Andreeff M, Marini F. Inflammation and tumor microenvironments: defining the migratory itinerary of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther. 2008;15:730–8. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studeny M, Marini FC, Champlin RE, Zompetta C, Fidler IJ, Andreeff M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for interferon-beta delivery into tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C, Kumar S, Chanda D, Kallman L, Chen J, Mountz JD, et al. Cancer gene therapy using mesenchymal stem cells expressing interferon-beta in a mouse prostate cancer lung metastasis model. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1446–53. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SH, Kim KS, Park SH, Suh YS, Kim SJ, Jeun SS, et al. The effects of mesenchymal stem cells injected via different routes on modified IL-12-mediated antitumor activity. Gene Ther. 2011;18:488–95. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebinger MR, Eddaoudi A, Davies D, Janes SM. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery of TRAIL can eliminate metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4134–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C, Kumar S, Chanda D, Chen J, Mountz JD, Ponnazhagan S. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells producing interferon-alpha in a mouse melanoma lung metastasis model. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2332–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger M, Clavreul A, Venier-Julienne MC, Passirani C, Sindji L, Schiller P, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells as cellular vehicles for delivery of nanoparticles to brain tumors. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Kastrup CJ, Ramanathan R, Siegwart DJ, Ma M, Bogatyrev SR, et al. Nanoparticulate cellular patches for cell-mediated tumoritropic delivery. ACS Nano. 2010;4:625–31. doi: 10.1021/nn901319y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Gordon PL, Koo WK, Marx JC, Neel MD, McNall RY, et al. Isolated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells engraft and stimulate growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: Implications for cell therapy of bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132252399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada H, Fujita J, Kinjo K, Matsuzaki Y, Tsuma M, Miyatake H, et al. Nonhematopoietic mesenchymal stem cells can be mobilized and differentiate into cardiomyocytes after myocardial infarction. Blood. 2004;104:3581–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JE, Konstantakos EK, Arm D, Caplan AI. In vivo osteogenesis assay: a rapid method for quantitative analysis. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1323–8. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgushi H, Kotobuki N, Funaoka H, Machida H, Hirose M, Tanaka Y, et al. Tissue engineered ceramic artificial joint — ex vivo osteogenic differentiation of patient mesenchymal cells on total ankle joints for treatment of osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4654–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon E, Muraglia A, Corsi A, Bianco P, Marcacci M, Martin I, et al. Autologous bone marrow stromal cells loaded onto porous hydroxyapatite ceramic accelerate bone repair in critical-size defects of sheep long bones. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;49:328–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000305)49:3<328::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solchaga LA, Temenoff JS, Gao J, Mikos AG, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM. Repair of osteochondral defects with hyaluronan- and polyester-based scaffolds. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisostomo PR, Wang Y, Markel TA, Wang M, Lahm T, Meldrum DR. Human mesenchymal stem cells stimulated by TNF-alpha, LPS, or hypoxia produce growth factors by an NF kappa B- but not JNK-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C675–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00437.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI, Dennis JE. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1076–84. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y, Han Z, Zhang S, Liu Y, Wei L. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tumor microenvironment. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:29. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ren G, Shi Y. The role of IL-6 in inhibition of lymphocyte apoptosis by mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:745–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Han ZP, Zhang SS, Jing YY, Bu XX, Wang CY, et al. Effects of inflammatory factors on mesenchymal stem cells and their role in the promotion of tumor angiogenesis in colon cancer. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25007–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Yang Y, Wang Z, Liu A, Fang L, Wu F, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor inhibits T helper 17 cell differentiation and confers treatment effects of neural progenitor cell therapy in autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2011;35:273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JY, Cho HJ, Kang HJ, Kim TS, Kim MH, Chung JH, et al. Pre-treatment of mesenchymal stem cells with a combination of growth factors enhances gap junction formation, cytoprotective effect on cardiomyocytes, and therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:933–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel LV, Lynch ME, van der Meulen MC, Yeager AE, Kornatowski MA, Nixon AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and insulin-like growth factor-I gene-enhanced mesenchymal stem cells improve structural aspects of healing in equine flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1392–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.20887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726–36. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Jing Y, Zhang S, Liu Y, Shi Y, Wei L. The role of immunosuppression of mesenchymal stem cells in tissue repair and tumor growth. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:8. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanichai M, Ferguson D, Prendergast PJ, Campbell VA. Hypoxia promotes chondrogenesis in rat mesenchymal stem cells: a role for AKT and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:708–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, et al. Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:386–98. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafei M, Campeau PM, Aguilar-Mahecha A, Buchanan M, Williams P, Birman E, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting CD4 Th17 T cells in a CC chemokine ligand 2-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2009;182:5994–6002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Amateis A, Indiveri F, Cancedda R, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1482–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, Mayer B, Parmelee A, Doi K, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E2-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]