Abstract

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that mediate RNA interference to suppress protein expression at the translational level. Accumulated evidence indicates that miRNAs play critical roles in various biological processes and disease development, including autoimmune diseases. Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are an unusual CD1d-restricted subset of thymus-derived T cells that are potent regulators of diverse immune responses. Our previous studies with the mouse model of bone marrow-specific Dicer deletion suggest the involvement of Dicer-dependent miRNAs in the development and function of iNKT cells. In the present study, to further dissect the functional levels of Dicer-dependent miRNAs in regulating iNKT cell development, we generated a mouse model with the Dicer deletion in the thymus. Our data indicate that lack of miRNAs following the deletion of Dicer in the thymus severely interrupted the development and maturation of iNKT cells in the thymus and significantly decreased the number of iNKT cells in the peripheral immune organs. miRNA-deficient peripheral iNKT cells display profound defects in activation and cytokine production upon α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) stimulation. Our results demonstrate a critical role of the miRNA-dependent pathway in the thymus in the regulation of iNKT cell development and function.

Keywords: autoimmunity, development, iNKT cells, microRNAs

Introduction

Natural killer T (NKT) cells comprise a unique subset of T cells that coexpress a rearranged T-cell receptor (TCR) and natural killer (NK) cell-related surface markers, including NK1.1.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The majority of these cells are restricted to a non-classical major histocompatibility complex I-related molecule, CD1d, and preferentially use an invariant TCR Vα14–Jα18 (mouse) or Vα24–Jα18 (human). These invariant NKT (iNKT) cells are almost uniformly reactive to the glycolipid ligand α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) presented by CD1d and can be identified using α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers. Upon activation, iNKT cells rapidly produce large amounts of cytokines, including interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-4, and play critical roles in the various immune responses, including the onset of cancer, infection and autoimmune diseases.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 It is believed that commitment to the iNKT cell lineage in the thymus involves a variety of signal transducers, transcription factors and cytokines. A number of gene deficiencies that disrupt iNKT cell development but leave conventional T cells unaffected provide evidence that iNKT cell differentiation is divergent from that in conventional T cells.3, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12 However, the detailed mechanisms and pathways for iNKT cell development are still unclear.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of 21–25 nt single-stranded noncoding small RNAs that are recognized as important regulators of gene expression through the inhibition of effective mRNA translation in animals.13, 14, 15 Dicer, a ribonuclease III enzyme, is required for the processing of mature and functional miRNAs. Thus, the deletion of Dicer provides a genetic test for the relevance of miRNAs in mammalian development. Emerging evidence suggests that miRNA-mediated gene regulation represents a fundamental layer of genetic programs at the post-transcriptional level and has diverse functional roles in animals, including development, differentiation and homeostasis.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Recent studies using a Cre–loxP tissue-specific Dicer deletion mouse model indicate that deletion of Dicer in the thymus results in impaired T-cell development, aberrant T helper (Th) cell differentiation and cytokine production, and increased thymocyte susceptibility to cell death.16 Dicer-deficient Th cells preferentially expressed IFN-γ, the hallmark effector cytokine of the Th1 lineage.17 With a similar mouse model, Cobb and colleagues found that depleting miRNAs by eliminating Dicer in thymus reduces CD4CD25Foxp3 T regulatory (Treg) cell numbers in the thymus, spleen and lymph nodes, which results in immune pathology in aged Dicer-deleted mice.22 More recently, using the Foxp3 Treg lineage-specific Dicer deletion mouse model, two independent studies found that Dicer-deficient Treg cells lost suppression activity in vivo and the mice rapidly developed fatal systemic autoimmune disease resembling the FoxP3 knockout (KO) phenotype.23, 24 These results support a central role for miRNAs in the Treg cell development, homeostasis and functional stability. iNKT cells are another major class of T cells with immune regulatory functions. Previous studies from our laboratory indicated that a Dicer deletion in bone marrow, mediated by Tie2-Cre, interrupted the development and functions of iNKT cells, and miRNAs expressed in endothelial cells are potent regulators of iNKT cell homeostasis.25 To more specifically clarify the role of miRNAs in both iNKT cell development differentiation and function, we generated a similar mouse model with Dicer deleted in the thymus, where iNKT cells develop. Here, we report that the deletion of Dicer in the thymus interrupts the development and maturation of iNKT cells, and that miRNA-deficient peripheral iNKT cells display profound defects in cytokine production and activation. Supporting our previous findings, our current results further confirmed the critical role of thymus miRNA-dependent pathways in the regulation of iNKT cell development and function.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice carrying a floxed allele of Dicer (Dicerfloxflox)26 were mated to CD4-Cre mice (Taconic Hudson, NY, USA) or Lck-Cre mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) to generate Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ or Dicerfl/flLCKcre+ conditional thymic Dicer KO mice. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free barrier unit. Handling of mice and experimental procedures were in accordance with institutional requirements for animal care and use.

Genotyping

Offspring were genotyped using the following PCR primer pairs: for Cre, 5′-TGATGAGGTTCGCAAGAACC-3′ and 5′-CCATGAGTGAACGAACCTGG-3′ (product size: 320 bp); and for Dicer, 5′-CCTGACAGTGACGGTCCAAAG-3′ (DicerF1) and 5′-CATGACTCTTCAACTCAAACT-3′ (product sizes: 420 bp, from the Dicerflox allele and 351 bp from the wild-type (WT) Dicer allele). The deletion allele was genotyped using primers DicerF1 and DicerDel (5′-CCTGAGCAAGGCAAGTCATTC-3′). The deletion allele produced a 471-bp PCR product whereas the WT allele resulted in a 1300-bp product.

Flow cytometry and antibodies

Anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-NK1.1 (PK136), anti-CD1d (1B1), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2), anti-IL-4 (11B11) antibodies, Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Unloaded and lipid PBS-57 (an analogue of a-GalCer)-loaded murine CD1d tetramers were provided by the National Institutes of Health Tetramer Facility (Atlanta, GA, USA). To detect 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation in lymphocytes harvested 24 h after mice received intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (1 mg/mouse), we used the BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). After surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized and then treated with DNase to expose incorporated BrdU. Subsequently, cells were stained with anti-BrdU antibody. Data were analyzed using CELLQuestPro software (BD Biosciences).

In vitro α-GalCer-induced proliferation assay

Thymocytes or splenocytes were stimulated with α-GalCer (100 ng/ml) or vehicle in T-cell complete medium. After 24 h, 0.5 µCi 3H-thymidine was added and cells were cultured for an additional 18 h. Cells were then harvested and counted in a microbetaplate counter (PerkinElmer, Covina, CA, USA).

In vivo α-GalCer-induced activation assay

For serum cytokine determination, mice were bled at 2 and 5 h after α-GalCer (2 µg/mouse) or vehicle injection (intravenous) and then euthanized. IFN-γ was detected by ELISA (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA). For intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were collected at 40 min after injection and cultured for an additional hour and stained with anti-B220, anti-CD3e and CD1d-tetramer followed by anti-IFN-γ or anti-IL-4 antibodies, and analyzed by SLRII fluorescence-activated cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed with two-tailed Student's t-test. P<0.05 is significant.

Results and discussion

Reduced numbers of iNKT cells in the absence of Dicer in the thymus

To understand the cell-autonomous role of miRNAs in iNKT cell biology, we generated a thymus-specific Dicer mutant mouse by crossing loxp-flanked Dicer gene mutation Dicerfl/fl mice26 with CD4-Cre transgenic mice. Mice that are homozygous for Dicerfl/fl with CD4-Cre expression are conditional Dicer deletion mice and were designated as Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ (Dicer KO), while the WT littermates were designated as Dicerfl/flCD4cre− (WT). Consistent with previous reports, the total number of thymocytes and the percentage of thymic CD4/CD8 lineage subsets in the Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice were normal compared with littermate controls, but CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells in KO mice were significantly reduced in both thymus and spleen (data not shown).18, 22, 26 In addition, flow cytometric analyses of lymphocytes in spleen and lymph nodes showed a marked reduction of the percentage of CD8+ T cells and a smaller reduction in CD4+ T cells, which are also in agreement with previous reports from the similar mouse model (data not shown).18, 26 To determine whether Dicer deletion in the thymus plays a role in iNKT cell development, we first assessed the frequency and number of iNKT cells in different immune organs. In contrast to the conventional T cells, the frequencies and absolute numbers of iNKT cells were markedly reduced in thymus as well as in spleen and liver in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice compared to their WT littermate controls (Figure 1a and b). We then tested the proliferation of thymic and splenic iNKT cells after in vitro α-GalCer stimulation. Consistent with the reduced iNKT cell numbers, the proliferation of iNKT cells was also significantly decreased in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice (Figure 1c). The reduction of iNKT cells in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice was not proportional to that of conventional T cells, further indicating that iNKT cell development is controlled by unique signaling transduction programs, which is dependent on Dicer-related miRNAs. Similarly, the reduced percentages and absolute numbers of iNKT cells in thymus, spleen and liver were also observed in Lck-Cre-mediated Dicer deletion mice, where the Cre-mediated Dicer deletion begins in an earlier T-cell development stage (double-negative 2 stage onward) (Figure 1d). Thus, deletion of miRNAs in the thymus drastically reduced the iNKT cell number in both thymus and peripheral lymph organs.

Figure 1.

Reduced number of iNKT cells in conditional thymic Dicer KO mice. (a) Reduced frequency of iNKT cells in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice. Thymocytes, splenocytes and hepatic leukocytes from 4- to 7-week-old Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerflox/flox WT littermates were stained with either PBS-57-loaded CD1d tetramers to identify the iNKT population or unloaded CD1d tetramers to define nonspecific binding. Plots were gated on lymphocytes. In the case of spleen and liver, B220+ B cells have been gated out. Results are representative of at least five experiments. (b) Absolute number of iNKT cells. Thymus, spleen and liver mononuclear cells were labeled with PBS-57/CD1d tetramers and an anti-TCRβ monoclonal antibody. Using the total cell count obtained from each organ, absolute numbers of iNKT lymphocytes (gated as shown in a) were determined. Numbers shown are mean±SD. Total iNKT cells were enumerated from six experiments and are shown plotted on a logarithmic scale. The differences marked with one asterisk was statistically different with P<0.05 and marked with two asterisks was P<0.005 using a two-tailed Student's t-test. (c) Proliferation of thymic and splenic iNKT cells in response to α-GalCer. Thymocytes and splenocytes of Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerflox/flox WT mice were cultured with 100 ng/ml α-GalCer for 48 h. Data are presented as mean±SD of one representative experiment of three. The difference marked with an asterisk was statistically different with P<0.01. (d) Reduced frequency of iNKT cells in Dicerfl/flLCKcre+ mice. Thymocytes, splenocytes and hepatic leukocytes from 4- to 7-week-old Dicerfl/flLCKcre+ KO and Dicerflox/flox WT littermates were stained with PBS-57-loaded CD1d tetramers and an anti-TCRβ monoclonal antibody to identify the iNKT population. Results are representative of at least three experiments. c.p.m., count per minute; iNKT, invariant natural killer; KO, knockout; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TCR, T-cell receptor; WT, wild-type; α-GalCer, α-galactosylceramide.

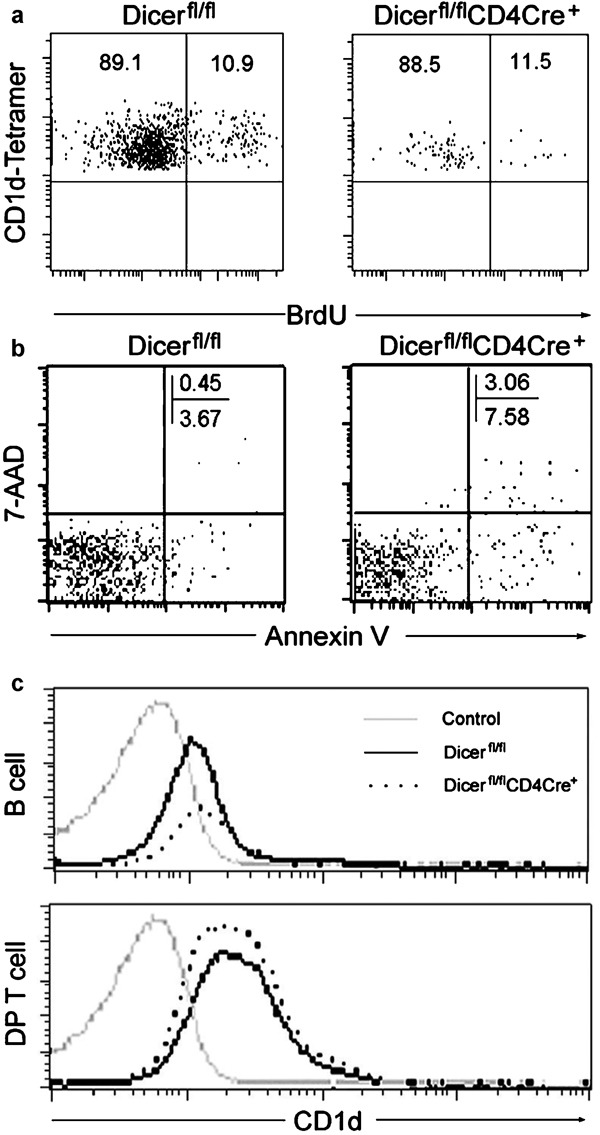

The reduction in number of thymic iNKT cells could originate from either an impaired proliferation of immature iNKT cells or increased cell death, or both. Previous studies using the similar mouse model indicated that peripheral conventional T cells in Dicer-deleted mice showed increased cell death and reduced proliferation with stimulation, which might be related to the reduced peripheral T-cell number in Dicer-deleted mice.17 To further address the iNKT cell number reduction mechanisms in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice, we performed a BrdU incorporation assay to evaluate the rate of in vivo iNKT cell proliferation. Surprisingly, as shown in Figure 2a, thymus iNKT cells from Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice incorporated BrdU at a comparable rate compared to WT control mice. Thus, the disparity between the comparable proliferation observed and the overall dramatically decreased numbers of iNKT cells in both thymic and peripheral compartments suggested that increased cell death might also be occurring in iNKT cells. Staining of fresh thymocytes using the apoptotic marker Annexin V in conjunction with the dye 7-AAD revealed significantly higher levels of apoptotic (Annexin V+ and 7-AAD+) iNKT cells in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice (2.45±0.89% versus 0.59±0.34%, P=0.005), suggesting the altered homeostasis of the iNKT cells in the absence of Dicer might play a role in the reduced iNKT cell number (Figure 2b). This finding is consistent with a more recent study using a thymus-specific Dicer deletion model.27 Given that mice lacking CD1d expression are deficient in iNKT cells, and CD1d expression in double-positive thymocytes is required for positive selection of iNKT cells28, we next tested CD1d expression in thymus. As shown in Figure 2c, CD1d expression in both CD4+CD8+ thymocytes and splenic B cells in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice is comparable to that of WT controls, indicating that the reduction of iNKT cell number in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice does not result from impaired CD1d expression.

Figure 2.

iNKT cell homeostasis and CD1d expression in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO mice. (a) Four- to 7-week-old mice received BrdU (1 mg/mouse) i.p. and were killed after 24 h. Thymocytes were stained with PBS-57-loaded CD1d tetramers, anti-TCRβ and anti-BrdU-specific antibodies. Depicted are BrdU+ iNKT cells gated in CD1d tetramers+ iNKT cells. Results are representative of two experiments. (b) Apoptosis in iNKT cells. Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerfl/fl WT iNKT cells from thymus were stained with Annexin V and 7-AAD. (c) Analysis of CD1d expression. Splenocytes or thymocytes from Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerfl/fl WT mice were stained with anti-CD1d antibody or isotype control and analyzed by flow cytometry. Expression levels of CD1d on splenic B cells (B220+) and thymus DP cells (CD4+CD8+) are shown. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments (n=3–5 pairs). BrdU, 5-bromodeoxyuridine; DP, double positive; iNKT, invariant natural killer; i.p., intraperitoneal; KO, knockout; TCR, T-cell receptor; WT, wild-type; 7-AAD, 7-aminoactinomycin D.

Altered iNKT cell development in the absence of Dicer in the thymus

After positive selection, immature iNKT cells undergo several well-defined developmental stages in the thymus. Immature iNKT cells are CD44loNK1.1−, which differentiate through the CD44hiNK1.1− stage to become CD44hiNK1.1+ cells after the terminal maturation step. Therefore, we analyzed the CD44/NK1.1 profiles of tetramer+ thymocytes to determine if iNKT cell maturation is defective in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice. The frequencies of mature CD44hiNK1.1+ iNKT cells were significantly reduced, while the percentage of immature CD44loNK1.1− iNKT cells was dramatically increased (Figure 3a and b), indicating the blockage of iNKT cell maturation from immature CD44loNK1.1− to the final mature CD44hiNK1.1+ stage. The thymic iNKT cell compartment is composed of well-defined subsets, and most mouse iNKT cells normally show the CD4+ or CD4−CD8− phenotype. Surprisingly, we found significantly increased CD4+CD8+ (P=0.027) and decreased CD4−CD8− iNKT cells (P=0.036) in the thymus in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice (Figure 3a and c). Previous studies indicated that the most immature iNKT cells detected by the CD1d tetramer in the thymus highly express heat stable antigen (HSA) and most are CD4+CD8+, while mature iNKT cells are NK1.1+Tet+HSAlow.29 We found that the majority of thymic iNKT cells in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice were indeed immature Tet+HSAhigh iNKT cells (data not shown), further suggesting an early blockage in iNKT cell development in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice. The defective iNKT cell developmental phenotype in the thymic Dicer deletion mouse model shows many similarities to results from our previous studies using the bone marrow Dicer deletion mouse model, which are suggestive of a cell-intrinsic defect in iNKT cells,25 but it still does not completely exclude the possible role of subtle defects in the thymic microenvironment in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice. With the generation of mixed bone marrow chimeras, a more recent study using a similar thymus Dicer deletion mouse model has revealed that the iNKT cell developmental defect caused by the thymus Dicer deletion is cell-intrinsic.27 Collectively, these results identified severe impairments at multiple iNKT cell development and maturation check points in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice compared to WT controls, further indicating that miRNAs are critical for iNKT cell development and maturation.

Figure 3.

The development of iNKT cells is altered in the absence of Dicer in thymus. (a) iNKT cell development in thymus. Thymocytes from Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerfl/fl WT mice were stained and CD44 and NK1.1 expression shown in gated CD1d-tetramer+TCRβ + iNKT cells along with percentages of cells in the indicated quadrants. Data are representative of at least five experiments. (b) Absolute number of iNKT cell subpopulations (mean±SD) based on their CD44 and NK1.1 expression patterns. (c) Analysis of subsets of iNKT cells in the thymus. CD1d-tetramer+TCRβ + cells were gated on thymocytes from Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerfl/fl WT mice and the relative frequencies of subsets defined by CD4 and CD8 expression were assessed. Graph shows summarized data from 5–7 mice. The difference marked with one asterisk was statistically different with P<0.05 and marked with two asterisks was P<0.005 using a two-tailed Student's t-test. iNKT, invariant natural killer T cells; KO, knockout; NK, natural killer; TCR, T-cell receptor; WT, wild-type.

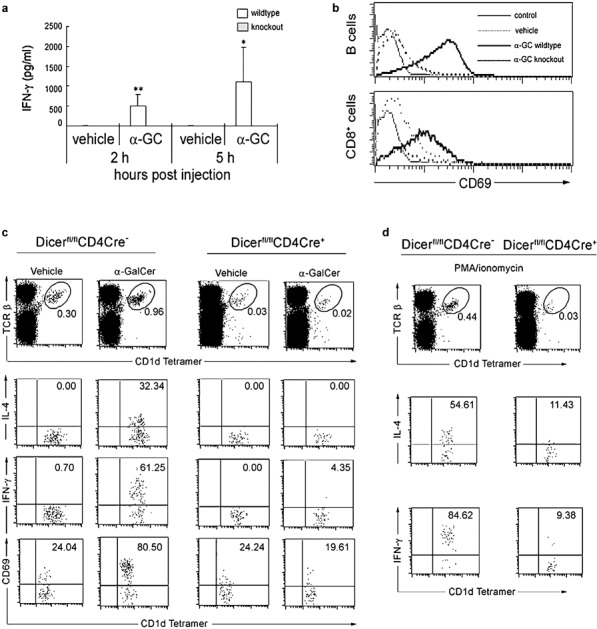

Impaired iNKT cell function in the absence of Dicer in the thymus

Previous studies using a thymus-specific Dicer-deletion mouse model suggested that, although Dicer is not critically required for the differentiation of the Th1 and Th2 lineages, Dicer-deficient Th cells preferentially expressed IFN-γ, the hallmark effector cytokine of the Th1 lineage.17 In addition, Dicer-deficient CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells produce higher levels of IL-4, IFN-γ and IL-10, but lost suppression activity in vivo.24 Activated iNKT cells rapidly produce cytokines, including IL-4 and IFN-γ, and, in turn, activate many other cell types, including T and B cells. As shown in Figure 4a and b, after α-Gal-Cer in vivo stimulation, IFN-γ production in WT mice was significantly increased and the expression of activation marker CD69 in CD8+ T and B cells was significantly upregulated. However, α-GalCer only induced a modest and constantly lower level of CD69 expression in both CD8+ T and B cells, as well as dramatically lower serum IFN-γ levels in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice compared to WT controls (Figure 4a and b). The lack of cytokine response to α-GalCer in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice could be explained by either the markedly reduced numbers of iNKT cells or the intrinsic defect of their activation and cytokine production. To test the latter possibility, we again injected mice intravenously with α-GalCer and examined the production of cytokines by iNKT cells with intracellular cytokine staining. As shown in Figure 4c, the number of splenic iNKT cells that express intracellular IL-4 or IFN-γ increased dramatically (32.34 and 61.25%, respectively) after in vivo α-GalCer stimulation (1.5 h); however, splenic iNKT cells from Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice had almost no response to α-GalCer stimulation. The defective cytokine production response to α-GalCer stimulation in Dicer-deficient mice could result from either a defect in cytokine synthesis or TCR signaling, thereby affecting the activation of iNKT cells. We therefore further investigated whether Dicer-deficient iNKT cells are activated normally upon α-GalCer stimulation. As shown in Figure 4c (bottom), α-GalCer stimulation induced dramatic upregulation of CD69, a downstream marker of TCR signaling, in iNKT cells from WT control mice. In contrast, α-GalCer stimulation did not upregulate CD69 expression in Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice at all, which strongly argues that miRNA deficiency in the thymus leads to a serious defect in TCR signaling. To further localize the block in the TCR-mediated signal transduction targeted by miRNAs, we stimulated splenocytes from both WT and Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin, which bypass proximal TCR-mediated signaling events and activate cells most likely at a stage proximal to protein kinase C and calcium flux.30 Three hours after stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin, over 50 and 80% of iNKT cells from WT mice stained positive for IL-4 and IFN-γ, respectively, compared to only 11 and 9% iNKT cells from Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ mice. Collectively, miRNAs seem to be critical in multiple signaling events in the related signaling pathways for iNKT cell activation and cytokine production, which is consistent with our previous findings from the bone marrow Dicer-deleted mouse model.25 Our current findings further suggest that the thymus is the major site for miRNAs to regulate iNKT cell development, maturation and function.

Figure 4.

The function of iNKT cells is altered in the absence of Dicer in the thymus. Dicerfl/flCD4cre+ KO and Dicerfl/fl WT littermate control mice were injected with 2 µg of α-GalCer or vehicle and subjected to the following analyses (a and b). (a) Serum was collected at 2 and 5 h for detection of IFN-γ by ELISA. The difference marked with one asterisk was statistically different with P<0.05 and with two asterisks was P<0.005. (b) The expression of CD69 by splenic B and CD8+ T cells was analyzed 5 h after injection. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (c) Splenocytes were collected at 40 min after injection with α-GalCer and then cultured in T-cell medium. Monesin was added to a final concentration of 3 µM, and the cells were incubated for an additional hour. The production of IFN-γ and IL-4 by splenic NKT cells was then analyzed with intracellular cytokine staining. (d) Splenocytes were left unstimulated or stimulated for 2 h in vitro with PMA and ionomycin. The production of IFN-γ and IL-4 by splenic NKT cells was then analyzed with intracellular cytokine staining. Results are representative of two independent experiments. IFN, interferon; iNKT, invariant natural killer; KO, knockout; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; TCR, T-cell receptor; WT, wild-type; α-GalCer, α-galactosylceramide.

Our data demonstrate that thymic miRNAs play an important role in iNKT cell development and maturation by regulating multiple check points, but not in mainstream T cells in the thymus. Multiple signaling events for iNKT cell activation and cytokine production are targeted by miRNAs. This finding opens up an avenue for future identification and mechanistic analyses of specific miRNAs differentially required for the proper development, function and homeostasis of iNKT cells, and points to targeted manipulation of the miRNAs and related pathways as a potential way of affecting iNKT cell function in experimental and clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. McManus for Dicer-loxP mice, R. Qi for assistance with artwork and the NIH Tetramer Facility for CD1d tetramer. This work was support by grants from Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International (1-2005-1039, 5-2006-688 and 5-2006-918) and American Diabetes Association (7-05-JF-30).

References

- Sharif S, Arreaza GA, Zucker P, Mi QS, Sondhi J, Naidenko OV, et al. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide treatment prevents the onset and recurrence of autoimmune Type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2001;7:1057–1062. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake S, Yamamura T. NKT cells and autoimmune diseases: unraveling the complexity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;314:251–267. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van KL. NKT cells: T lymphocytes with innate effector functions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi QS, Meagher C, Delovitch TL. CD1d-restricted NKT regulatory cells: functional genomic analyses provide new insights into the mechanisms of protection against Type 1 diabetes. Novartis Found Symp. 2003;252:146–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi QS, Ly D, Zucker P, McGarry M, Delovitch TL. Interleukin-4 but not interleukin-10 protects against spontaneous and recurrent Type 1 diabetes by activated CD1d-restricted invariant natural killer T-cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:1303–1310. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg M, Engel I. On the road: progress in finding the unique pathway of invariant NKT cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg M, Gapin L. Natural killer T cells: know thyself. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5713–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701493104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupin E, Kinjo Y, Kronenberg M. The unique role of natural killer T cells in the response to microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:405–417. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowski C, Bendelac A. Signaling for NKT cell development: the SAP–FynT connection. J Exp Med. 2005;201:833–836. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage AK, Constantinides MG, Han J, Picard D, Martin E, Li B, et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity. 2008;29:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Seo KH, Wong HK, Mi QS. MicroRNAs and immune regulatory T cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:524–527. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BS, Nesterova TB, Thompson E, Hertweck A, O'Connor E, Godwin J, et al. T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1367–1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muljo SA, Ansel KM, Kanellopoulou C, Livingston DM, Rao R, Rajewsky K. Aberrant T cell differentiation in the absence of Dicer. J Exp Med. 2005;202:261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, et al. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez Y, Fernández-Hernando C, Yu J, Gerber SA, Harrison KD, Pober JS, et al. Dicer-dependent endothelial microRNAs are necessary for postnatal angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804597105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralov SB, Muljo SA, Galler GR, Krek A, Chakraborty T, Kanellopoulou C, et al. Dicer ablation affects antibody diversity and cell survival in the B lymphocyte lineage. Cell. 2008;132:860–874. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi F, Izu Y, Hayata T, Hemmi H, Nakashima K, Nakamura T, et al. Osteoclast-specific Dicer gene deficiency suppresses osteoclastic bone resorption. J Cell Biochem. 2009;109:866–875. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BS, Nesterova TB, Thompson E, Hertweck A, O'Connor E, Godwin J, et al. A role for Dicer in immune regulation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2519–2527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston A, Lu LF, O'Carroll D, Tarakhovsky A, Rudensky AY. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway safeguards regulatory T cell function. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1993–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Jeker LT, Fife BT, Zhu S, Anderson MS, McManus MT, et al. Selective miRNA disruption in T reg cells leads to uncontrolled autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1983–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Seo KH, He HZ, Pacholczyk R, Meng DM, Li CG, et al. Tie2cre-induced inactivation of the miRNA-processing enzyme Dicer disrupts invariant NKT cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10266–10271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811119106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedeli M, Napolitano A, Wong MP, Marcais A, de Lalla C, Colucci F, et al. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway controls invariant NKT cell development. J Immunol. 2009;183:2506–2512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapin L, Matsuda JL, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. NKT cells derive from double-positive thymocytes that are positively selected by CD1d. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:971–978. doi: 10.1038/ni710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlagha K, Wei DG, Veiga J, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Characterization of the early stages of thymic NKT cell development. J Exp Med. 2005;202:485–492. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PJ, Pai SY, Brigl M, Besra GS, Gumperz J, Ho IC. GATA-3 regulates the development and function of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:6650–6659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]