Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is a leading cause of mortality among women in the world. To date, a number of molecules have been established as disease status indicators and therapeutic targets. The best known among them are estrogen receptor-α (ER-α), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER-2/neu. About 15%–20% BC patients do not respond effectively to therapies targeting these classes of tumor-promoting factors. Thus, additional targets are strongly and urgently sought after in therapy for human BCs negative for ER, PR and HER-2, the so-called triple-negative BC (TNBC). Recent clinical work has revealed that CC chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) is strongly associated with the progression of BC, particularly TNBC. How CCL5 contributes to the development of TNBC is not well understood. Experimental animal studies have begun to address the mechanistic issue. In this article, we will review the clinical and laboratory work in this area that has led to our own hypothesis that targeting CCL5 in TNBCs will have favorable therapeutic outcomes with minimal adverse impact on the general physiology.

Keywords: triple negative breast cancer, CCL5, myeloid derived suppressor cell, immunotherapy

CCL5 in immunity and in inflammatory diseases

Chemokines are small soluble proteins that act as molecular signals to induce cellular migration during inflammation. Chemokines and chemokine receptors are expressed by many types of cancers cells. Locally produced chemokines can induce inflammatory tumor-infiltrating cells, facilitate angiogenesis, promote growth or survival, and stimulate tumor cell metastasis.1,2,3

CC chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), also known as RANTES (Regulated upon Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed, and Secreted), belongs to the CC chemokine family whose members include monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, MCP-2, MCP-3, I-309, macrophage inhibitory protein-1α and macrophage inhibitory protein-1β. CCL5 was first identified in a search for genes that were expressed differentially in activated T cells but not in B cells.4 In T lymphocytes, CCL5 expression is regulated by Kruppel-like factor 13.4,5,6 CCL5 is also expressed in macrophages, platelets, synovial fibroblasts, tubular epithelium and certain types of tumor cells. CCL5 plays an active role in recruiting a variety of leukocytes into inflammatory sites including T cells, macrophages, eosinophils and basophils. In collaboration with certain cytokines that are released by T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, CCL5 also induces the activation and proliferation of particular natural-killer cells to generate CC chemokine-activated killer cells.7 CCL5 produced by CD8+ T cells and other immune cells has been shown to inhibit HIV entry into target cells.8 The activities of CCL5 are mediated through its binding to CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5.9

Genetic evidence exists that links CCL5 with numerous human diseases, such as coronary artery disease,10 multiple sclerosis,11 rheumatoid arthritis,12,13 asthma and atopy,14,15,16,17 atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome, atopic dermatitis,18 hepatitis C virus infection,19,20 heart graft rejection21 and systemic lupus erythematosus.22,23

CCL5 and human breast cancer (BC)

The human CCL5 gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 17,24 the same area Her2/neu is encoded and an area amplified in 30% BC patients.25 Tumor-derived CCL5 is detected in many clinical specimens of breast and cervical cancers; greater plasma levels in patients with progressive and more advanced disease than those in remission,26,27,28 and it constitutes a prominent part of a poor prognosis signature of inflammatory BC.29,30 An analysis of large core needle biopsies of 113 invasive breast carcinomas revealed that the concentration of CCL5 was significantly higher in the groups of patients with axillary lymph node metastasis than those without.31 Most BC-derived cell lines spontaneously produce large amounts of CCL5, and the incidence of CCL5 expression detected in tissue sections of breast carcinomas is considerably higher than in normal duct epithelial cells or in those of benign breast lumps.32 CCL5 expression was speculated to be indicative of an ongoing, but as yet undetectable, malignant process.32 A Cox proportional hazard model-based univariate analysis of 142 BC patients indicated little predictive value of CCL5 for disease progression in stage I BC patients. In contrast, the expression of CCL5, the absence of estrogen receptor (ER)-α and the lack of progesterone receptor (PR) expression in stage II patients increased significantly the risk for disease development. Conversely, the combinations of CCL5-negative/ER-α-positive and CCL5-negative/PR-positive in the stage II group as a whole were strongly correlative with an improved prognosis.33

Furthermore, concomitant expression of the CCL5 and MCP-1 was observed in advanced human BC,34 suggesting tumor-promoting interactions between these two chemokines. By immunohistochemistry analysis for the expression of CCL2, CCL5, IL-1β and TNF-α, Soria et al. examined four groups of patients diagnosed with (i) benign breast disorders; (ii) ductal carcinoma in situ; (iii) invasive ducal carcinoma (IDC) without relapse; and (iv) IDC with relapse, respectively. The analyses revealed significant associations between CCL2 and CCL5 and between IL-1β and TNF-α, respectively, in the tumor cells from ductal carcinoma in situ and IDC-without-relapse patients. The expression of CCL2 and CCL5 in the IDC-with-relapse group was associated with further elevated expression of IL-1β and TNF-α.35

In human breast tumor cells, CCL5-containing vesicles on microtubules traffic from the endoplasmic reticulum to the post-Golgi stage before CCL5 is released, and this process is controlled by the stiffness of the actin cytoskeleton in a manner dependent on the (43)TRKN(46) sequence of the 40 s loop of CCL5.36

CCL5 in experimental mouse mammary tumors

The mouse CCL5 is 68-amino acid long and highly basic, shares 85% homology with human CCL5. Most human BC studies in vivo are conducted in immunodeficient mice such as SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) with human BC cell lines such as MCF7, Hs578T, MDA-MB-231 and T47D. Murine mammary carcinoma can be induced in several ways, usually by overexpression of oncogenes such as Wnt-1, first identified in mouse mammary tumors as a protooncogene activated by insertion of the mammary tumor virus genome. The Wnt-1-mediated mitogenic effect is not dependent on estrogen stimulation, evidenced by tumor formation in ER-α-null mice, albeit after an increased latency.37 Mammary tumor development induced by Wnt-1 expression is facilitated by other genetic lesions such as inactivation of p53 and overexpression of Fgf-3.37

Triple negative BC

ER-α-, PR- and HER-2/neu-negative BC, or triple-negative BC (TNBC), is a highly malignant disease that traditionally lacks a clearly definable therapeutic target. It was originally described by Perou et al. as distinct molecular subgroups of BCs differentiated by their gene expression profiles associated with prognosis. These subgroups comprised of a normal breast–like group, the basal epithelial-like group, an ERBB2-overexpressing group and the ER-positive luminal A and B groups.38,39 Based on their global gene expression profiles, about 70% of breast tumors identified as triple negative by immunohistochemistry belong to the basal-like group of BCs.40 Interestingly, a large proportion of BCs arising in women with germline BRCA1 mutations exhibit the triple-negative phenotype and also fall within the basal-like group.41 It is now a well-accepted notion that polyADP-ribose inhibition within BRCA-deficient cancer cells can effective block the residual DNA repair machinery, resulting in synthetic lethality.42

4T1, an inflammatory murine TNBC model

A very commonly used immunocompetent, syngeneic and triple negative mouse model of mammary tumor development is the 4T1 cell line, which was first isolated from a single spontaneously arising mammary tumor from a BALB/cfC3H mouse (murine mammary tumor virus).43 4T1 is an excellent model system for BC research due to the oncologically and immunologically well-characterized tumor development. The 4T1 tumor closely mimics human BC in its physical location, proliferative and metastatic characteristics.44 The growth and metastatic properties of 4T1 cells closely resemble stage IV BC,45 and it is a TNBC.44 4T1 tumor instinctively migrates primarily through a hematogenous route to many distant organs including the lung, heart, bone, brain and liver.46 4T1 is also poorly immunogenic in that only slight delays in tumor growth against tumor challenge is attained via immunization with irradiated 4T1 cells, inadequate to protect the host.47 Immune suppression in the 4T1 model has been attributed in part to a signal transduction and transcription 6-dependent inhibition of the development of tumor-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity.48 Nevertheless, 4T1 are capable of stimulating an immune response of the host because it has been shown that effective anti-tumor immune responses can be induced by dendritic cell mixed with irradiated tumor cells as a source of uncharacterized tumor antigens.49 In particular, substantial reduction in tumor size and in spontaneous metastases in the lungs of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice as well as prolonged survival time was accomplished by IL-12 administration.50,51 These effects were accompanied by increased natural killer activity and enhanced levels of IFN-γ in tumor-draining lymph node cells obtained from 4T1 tumor-bearing mice treated with IL-12.50 Due to the unique characteristics of 4T1 tumor, this model has been used to investigate important issues such as immunotherapy,52 metastasis,53 anti-angiogenesis therapy54 and multiple chemotherapy treatments.55,56

The 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma cell line expresses different levels of CCL5.57 In this model, tumor-derived CCL5 is able to stimulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9, which can facilitate tumor angiogenesis and hereby, promote growth in vivo. Tumor-derived CCL5 has also been shown to impede anti-tumor T-cell responses and heighten the progression of murine mammary carcinoma.57 Met-CCL5, a dominant negative mutant of CCL5, is able to inhibit experimental breast tumor growth in vivo.58

Consistent with its tumor-promoting role in BC, CCL5, along with CCL2 (also called MCP-1), has been shown to facilitate many types of tumor-stimulating cross-talks between the tumor and cells of the surrounding microenvironment. CCL5 can cause changes in the composition of the different leukocyte cell types at the tumor site by accumulating harmful tumor-associated macrophages and by constraining potential anti-tumor T cell activities. CCL5 expressed by osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells of the tumor microenvironment plays a role in breast metastatic processes. CCL5 acts directly on tumor cells to promote their promalignancy phenotype, by stimulating their migratory and invasion-related activities.59

Transcriptional regulation of CCL5 gene expression in mammary tumor cells

Previously, it was shown that 4T1 tumor cells constitutively produce high levels of CCL2 and CCL5.60 The high level of CCL5 may play an important role in the tumor's growth, metastasis and resistance to host immunosurveillance.57 To understand the molecular basis for the high spontaneous expression of CCL5 at the transcriptional level, we performed experiments in which we transfected a mouse ccl5 gene promoter linked to the firefly luciferase reporter61 into 4T1 cells by electroporation, and measured luciferase activity from the wild type ccl5 promoter and the ccl5 promoter in which the critical NF-κB site was mutated by base-substitution.61 As shown in Figure 1, the wild-type ccl5 promoter was robustly active in 4T1 cells without any stimulation. This activity was greatly diminished when the NF-κB site was mutated. The IL-12p40 promoter, which is active only in myeloid cells following activation by pathogens,62 was totally inactive in 4T1 cells, demonstrating the selectivity of ccl5 gene activation in 4T1 tumor cells. These data suggest that the ccl5 gene is constitutively and highly expressed due to its transcriptional activation by a mechanism that is critically dependent on NF-κB. Importantly and relevant to this study, NF-κB activation is a hallmark of dysregulated cell growth, malignant transformation, and resistance to apoptosis.63

Figure 1.

Spontaneous ccl5 gene transcription in 4T1 cells. 4T1 tumor cells (107) were electroporated with 10 µg murine ccl5 promoter–reporter construct (−979 to +8),61 or its NF-κB mutant (a 3-base-substitution at −81 to −79. Also see Figure 3 below), or the IL-12 p40 promoter construct, which is expressed in a highly cell-type specific manner.62 Each electroporated sample was split into three equal wells as triplicates. Cells were harvested 48 h later. Cell lysates were used for luciferase activity measurement using a luminometer. Total protein content in each sample was used to normalize the data variation due to cell number differences. Data represent triplicate reading for each sample with standard deviation. CCL5, CC chemokine ligand 5.

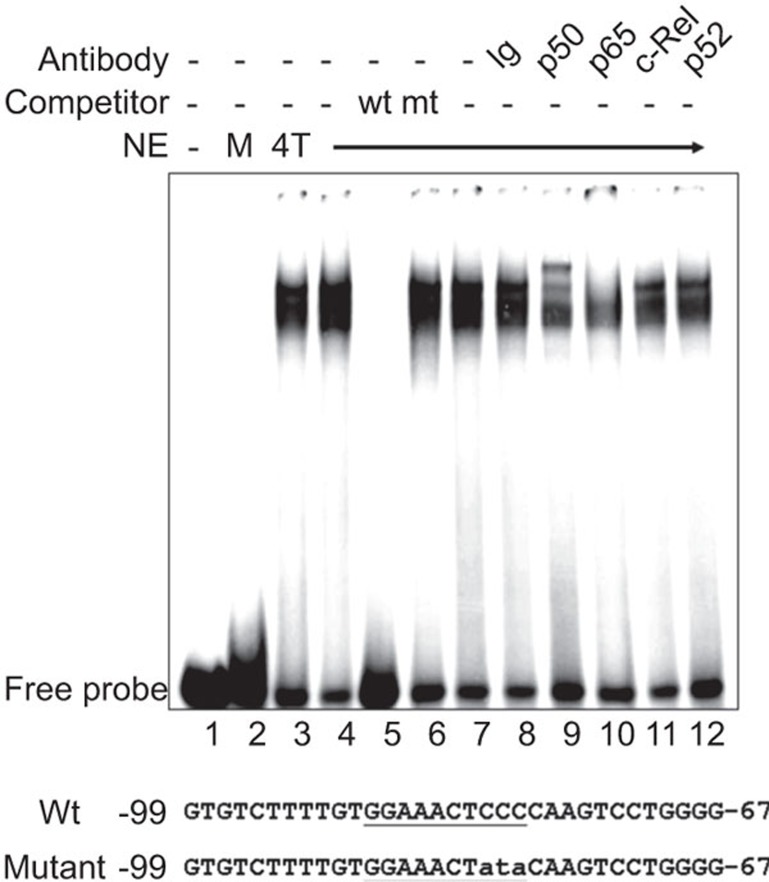

Spontaneous high NF-κB-binding activity in 4T1 tumor cells

Consistent with the total dependence of the ccl5 gene transcription on the critical NF-κB element in its promoter, spontaneous and sequence-specific nuclear binding activity of NF-κB to the cognate ccl5 gene promoter between −99 and −67 was observed (Figure 2). NF-κB binding to the ccl5 gene promoter was observed only in 4T1 cells (lane 3), but not in resting primary macrophages (lane 2). The binding was competed off efficiently with wild-type ‘cold' probe (lane 5), but not by the NF-κB mutant probe (lane 6). It was specifically ‘supershifted' by antibodies against NF-κB p50 (lane 9) and p65 (lane 10), but not by those against c-Rel (lane 11), p52 (lane 12) or control IgG (lane 8). These results suggest that spontaneously active NF-κB activity in the nucleus of 4T1 cells, composed mainly of p50 and p65, may be responsible for the constitutive expression of CCL5.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous NF-κB-binding activity in 4T1 tumor cells. Nuclear extracts (NE) were isolated from 4T1 cells (4T) and primary mouse macrophages (M). Five µg of NE were mixed with the wild type (wt) or mutant (mt) NF-κB probe (their sequences presented with the critical core sequence underlined). Various competitors and NF-κB antibodies and control Ig were used to assess the binding specificity and selectivity. The complexes were resolved on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel.

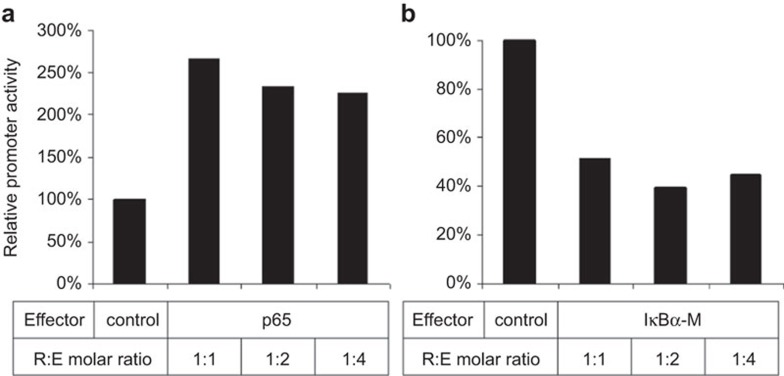

To support this hypothesis, we introduced NF-κB p65 into 4T1 cells by electroporation and measured ccl5 promoter activity. As shown in Figure 3a, p65 expression was able to further enhance ccl5 transcription. Conversely, when we introduced a constitutively active form of IκBα, which acts as a dominant negative against the endogenous IκBα,64 it inhibited ccl5 gene transcription (Figure 3b). It is noteworthy that the IκBα mutant did not completely inhibit ccl5 gene transcription even at very high concentrations.

Figure 3.

Role of NF-κB in ccl5 gene transcription in 4T1 cells. 4T1 tumor cells (107) were electroporated with the murine ccl5 promoter–reporter construct, together with an expression vector for NF-κB p65 (a), or an IκBα mutant (b), at increasing amounts in terms of molar ratios of reporter (R) to effector (E). Cells were harvested 48 h later. Cell lysates were used for luciferase activity measurement. Results are expressed as relative activity to that of ccl5 promoter alone without the effector (p65 or IκBα-M).

Additional transcription factors may also contribute to ccl5 transcription

The observation that the IκBα mutant could not completely inhibit ccl5 gene transcription (Figure 3b) suggests that additional transcription factors may be involved through the NF-κB site (Figure 1). It has been demonstrated that a Ras-independent, phosphoinositide-3 kinase-dependent, c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent phosphorylation of c-Jun in 4T1 cells results in binding of an AP-1 c-Jun homodimer to the osteopontin promoter.45 We tested if AP-1 was involved in driving ccl5 gene transcription in 4T1 cells by using a dominant negative mutant of AP-1 called A-Fos. A-Fos was engineered on the backbone of the Fos leucine zipper to which an acidic, amphipathic protein sequence was added at the N terminus. This acidic sequence substitutes the normal basic region critical for DNA binding. The heterodimeric coiled-coil structure formed between the acidic extension and the Jun basic region dramatically stabilizes the complex and prevents the latter region from binding to DNA.65 In addition, several studies have demonstrated that agents that increase intracellular cyclic AMP inhibit the secretion of CCL5 induced by TNF-α66,67 via a CRE-dependent and AP-1-independent pathway.68 Thus, we used a dominant negative mutant of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), called A-CREB. A-CREB was assembled by melding the N-terminus of the CREB leucine zipper domain with a constructed acidic amphipathic extension. A coiled-coil extension of the leucine zipper is formed when the acidic extension of A-CREB interacts with the basic region of the wild type CREB, rendering the latter domain unable to bind DNA.69 As shown in Figure 4, inhibiting AP-1 with A-fos resulted in a strong decrease of ccl5 transcription, while inhibiting CREB with A-CREB had the reverse effect, suggesting that the endogenous AP-1 may be an important transcriptional activator of ccl5, while CREB may be a repressor. Combining IκBα-M and A-Fos did not result in greater inhibition of ccl5 transcription than either effector alone, suggesting that the NF-κB and AP-1 pathways operate independently without interaction. Paradoxically, when IκBα-M and A-CREB were used together, the stimulatory effect of A-CREB on ccl5 gene transcription was abrogated, suggesting that CREB may inhibit ccl5 transcription in an NF-κB-dependent manner.

Figure 4.

Role of AP-1 and CREB in ccl5 gene transcription in 4T1 cells 4T1 tumor cells (107) were electroporated with the murine ccl5 promoter–reporter construct, together with an expression vectors for IκBα mutant, A-Fos, and A-CREB at the reporter∶effector molar ratio of 1∶1. Cells were harvested 48 h later. Cell lysates were used for luciferase activity measurement. Results are expressed as relative activity to that of ccl5 promoter alone without the effectors. CREB, cyclic AMP response element binding protein.

The data shown in Figure 4 suggests that AP-1 may be an important transcriptional activator for CCL5 expression. Consistent with this notion, we have observed strong and spontaneous AP-1 binding activity at this site (data not shown). Taken together, NF-κB and AP-1 collectively contribute to the robust ccl5 gene transcription associated with the properties of 4T1 tumor.

CCL5 and other cancers

A number of other cancer types have been shown to express CCL5,70,71,72,73,74 induce inflammatory cell migration into the tumor site71,73,74 and enhance tumor growth.70 There is evidence that inflammatory chemokines including CCL5 expressed by prostate cells may act directly on the growth and survival of hormone-driven prostate cancer cells.75 In a Japanese study, it was found that serum CCL5 concentration was significantly elevated in the ovarian cancer patients compared to the benign ovarian cyst patients as controls correlating with the stage of disease and the extent of residual tumor mass.76 Mantle cell lymphomas acquire increased expression of CCL4, CCL5 and 4-1BB-L, which are implicated in cell survival.77 CCL5 expression is a predictor of survival in stage I lung adenocarcinoma.78 Thus, CCL5 may well represent a cancer-promoting factor in a broad sense as a result of chronic inflammation caused by infection or other types of stresses.

Tumor growth independent of tumor-derived CCL5

Recent experimental work has indicated that the cellular source of CCL5 expression may not be as simple and straightforward as people originally thought. One study investigated the role of CCL5 produced by tumor cells in promoting growth or metastasis of BC. Two murine mammary tumor models were used. The 4T1 model spontaneously expresses CCL5 and is metastatic, and the 168 tumor does not intrinsically produce CCL5 and is not metastatic. CCL5 expression in the 4T1 tumor was silenced via RNA interference, while the 168 tumor was engineered to stably express a CCL5 transgene. In both models, no correlation was found of tumor-derived CCL5 expression with MHC expression, growth rate or metastatic ability of the tumors.79,80 These paradoxical results imply that tumor-derived CCL5 expression cannot account for the highly aggressive nature of the 4T1 tumor.

Hematopoietic CCL5 and myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Our group has recently obtained data showing that CCL5-deficient mice, which develop normally with phenotypically intact immune compartments, are nonetheless resistant to advanced 4T1 mammary tumor growth. Bone marrow chimera and adoptive transfer experiments demonstrate that hematopoietically derived CCL5 plays a dominant role in this phenotype. Further, the absence of hematopoietic CCL5 causes aberrant generation of CD11b+Gr-1+, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the bone marrow in response to tumor growth by accumulating Ly6Chi and Ly6G+, atypical MDSCs with impaired capacity to suppress cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. Moreover, tumor-infiltrating MDSCs show increased CCL5 expression during tumor progression at a greater level than the tumor cells. These properties of CCL5 with respect to MDSCs have also been observed in two mouse models of spontaneously induced mammary tumors.

MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of cells comprised of myeloid progenitors and immature myeloid cells that contribute to negative regulation of immune responses to malignant growth.81 Previous studies have shown in various mouse models that depletion of MDSCs from tumors or spleens restores anti-tumor T-cell responses.82,83,84,85,86,87 The accumulation of MDSCs is influenced by disturbances of cytokine homeostasis in pathological conditions, which stimulate myelopoiesis and inhibit the differentiation of mature myeloid cells.81 Recently, MDSCs have been defined more precisely in mice by two epitopes recognized by the Gr-1 antibody: Ly6G and Ly6C. Normally, CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6Chi MDSCs have monocytic phenotype, whereas CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clow MDSCs are of granulocytic phenotype.81

In the 4T1 model, our studies further indicate that there is intimate cooperation between tumor-derived macrophage colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor with CCL5 in the development of immunosuppressive MDSCs that promotes tumor expansion. Antibody-mediated, systemic blockade of CCL5 inhibits tumor progression and strongly enhances the efficacy of vaccination against poorly immunogenic 4T1 tumors. Importantly, CCL5 helps maintain the immunosuppressive capacity of human MDSCs.

Thus, our study has uncovered a highly novel and important chemokine-independent activity of CCL5. Since immune suppression plays a crucial role in promoting tumor progression and failure of cancer vaccines, among which MDSCs are the major immunosuppressive effectors, different strategies have been proposed to overcome MDSC-mediated immunosuppression. Our study also suggests that targeting CCL5 in TNBC could decrease the immunosuppression activity of MDSCs, improve vaccine efficacy against poorly immunogenic tumors and reduce BC progression and metastasis.

CCL2 and CXCL8 in TNBC

It should be pointed out that CCL2 (also called MCP-1), like CCL5, has been shown in many studies to play an important role as well in ER-α-negative breast cancer and TNBC.88 However, its activity as a regulator of MDSCs has not been explored. In addition, several CXC chemokines are believed to play significant roles in TNBC formation and progression. For example, CXCL8 (IL-8) expression is negatively linked to ER-α status of breast cancer and CXCL8 expression is associated with a higher invasiveness of cancer cells.89 CXCL8 was identified as a key factor involved in breast cancer invasion and angiogenesis.36 However, the role of CXCL8 derived from non-tumor cells in TNBC progression and its role outside the conventional chemotactic activities have not been established. Thus, generally speaking, chemokines are double-edged sword. They can be instrumental in mobilizing cells in the face of pathogenic infections in order to fight off the invaders. On the other hand, they can also be culprits in assisting inflammatory tumors cells to initiate, propagate and spread.

Rationale for targeting CCL5 in TNBC therapy

The rationale for targeting CCL5 in TNBC therapy is based on the following considerations: (i) CCL5 appears to be critical for mammary tumor growth while dispensable for general physiology and broad immunity; (ii) CCL5 knockout mice develop and live normally; their steady-state immune compartments also appear intact; (iii) they exhibit delayed clearance of parainfluenza virus;90 (iv) CCR5 knockout mice show increased parasitemia of Trypanosoma cruzi,91 but remain resistant to Cryptosporidium parvum infection,92 and able to control Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection;93 and (v) CCR5delta32-homozygous human individuals are resistant to HIV infection and have no general immune deficiency.94 Thus, targeted inhibition of CCL5, particularly in the bone marrow and in the tumor-infiltrating MDSC microenvironment in TNBC patients, may have strong therapeutic impact without overt toxicity. Future studies should be directed towards identifying efficient ways for targeted delivery of therapeutic molecules (antibody, peptide, small molecule inhibitor, siRNA, etc.) to sites where MDSCs are generated (bone marrow) and where they function (tumor mass). This kind of highly selective, targeted strategy can alleviate concerns of unintended effects. For example, in patients with breast cancer who are also infected with HIV, anti-CCL5 therapies may promote the spread of HIV because CCL5 is a competitor against HIV binding to its receptor CCR5. In this scenario, simultaneous use of a small molecule CCR5 blocker together with the anti-CCL5 therapeutic agent should be able to reduce the level of CCL5 without accidentally helping the cellular entry of HIV.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the grant support KG091243 from Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation to XM.

References

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taichman RS, Cooper C, Keller ET, Pienta KJ, Taichman NS, McCauley LK. Use of the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 pathway in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1832–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes S, Mira E, Colomer R, Montero S, Real LM, Gomez-Mouton C, et al. CCR5 expression influences the progression of human breast cancer in a p53-dependent manner. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1381–1389. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall TJ, Jongstra J, Dyer BJ, Jorgensen J, Clayberger C, Davis MM, et al. A human T cell-specific molecule is a member of a new gene family. J Immunol. 1988;141:1018–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song A, Chen YF, Thamatrakoln K, Storm TA, Krensky AM. RFLAT-1: a new zinc finger transcription factor that activates RANTES gene expression in T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1999;10:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song A, Nikolcheva T, Krensky AM. Transcriptional regulation of RANTES expression in T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 2000;177:236–245. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghazachi AA, Al-Aoukaty A, Schall TJ. CC chemokines induce the generation of killer cells from CD56+ cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:315–319. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakianathan DR, Kuta EG, Artis DR, Skelton NJ, Hebert CA. Distinct but overlapping epitopes for the interaction of a CC-chemokine with CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9642–9648. doi: 10.1021/bi970593z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeoni E, Winkelmann BR, Hoffmann MM, Fleury S, Ruiz J, Kappenberger L, et al. Association of RANTES G-403A gene polymorphism with increased risk of coronary arteriosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1438–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade-Andavolu R, Comings DE, MacMurray J, Vuthoori RK, Tourtellotte WW, Nagra RM, et al. RANTES: a genetic risk marker for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:536–539. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1080oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CR, Guo HR, Liu MF. RANTES promoter polymorphism as a genetic risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis in the Chinese. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makki RF, Al Sharif F, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Ollier WE, Hajeer AH. RANTES gene polymorphism in polymyalgia rheumatica, giant cell arteritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:391–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer AA, Spiteri MA, Bianco A, Hepple M, Jones PW, Strange RC, et al. The −403 G→A promoter polymorphism in the RANTES gene is associated with atopy and asthma. Genes Immun. 2000;1:509–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdulhadi SA, Helms PJ, Main M, Smith O, Christie G. Preferential transmission and association of the −403 G→A promoter RANTES polymorphism with atopic asthma. Genes Immun. 2005;6:24–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao TC, Kuo ML, See LC, Chen LC, Yan DC, Ou LS, et al. The RANTES promoter polymorphism: a genetic risk factor for near-fatal asthma in Chinese children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1285–1292. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizawa N, Yamaguchi E, Konno S, Tanino Y, Jinushi E, Nishimura M. A functional polymorphism in the RANTES gene promoter is associated with the development of late-onset asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:686–690. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-090OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma GT, Falus A, Bojszko A, Krikovszky D, Szabo T, Nagy A, et al. Lack of association between atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome and polymorphisms in the promoter region of RANTES and regulatory region of MCP-1. Allergy. 2002;57:160–163. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1s3361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellier S, Frodsham AJ, Hennig BJ, Klenerman P, Knapp S, Ramaley P, et al. Association of genetic variants of the chemokine receptor CCR5 and its ligands, RANTES and MCP-2, with outcome of HCV infection. Hepatology. 2003;38:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promrat K, Liang TJ. Chemokine systems and hepatitis C virus infection: is truth in the genes of the beholders. Hepatology. 2003;38:1359–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeoni E, Vassalli G, Seydoux C, Ramsay D, Noll G, von Segesser LK, et al. CCR5, RANTES and CX3CR1 polymorphisms: possible genetic links with acute heart rejection. Transplantation. 2005;80:1309–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000178378.53616.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CH, Yao TC, Chung HT, See LC, Kuo ML, Huang JL. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of RANTES and the regulatory region of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 among Chinese children with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2062–2067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye DQ, Yang SG, Li XP, Hu YS, Yin J, Zhang GQ, et al. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of RANTES in Han Chinese and their relationship with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005;297:108–113. doi: 10.1007/s00403-005-0581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlon TA, Krensky AM, Wallace MR, Collins FS, Lovett M, Clayberger C. Localization of a human T-cell-specific gene, RANTES (D17S136E), to chromosome 17q11.2–q12. Genomics. 1990;6:548–553. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90485-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Ghafari S, Zhao M. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for HER-2/neu amplification of breast carcinoma in archival fine needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:471–476. doi: 10.1159/000326190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azenshtein E, Luboshits G, Shina S, Neumark E, Shahbazian D, Weil M, et al. The CC chemokine RANTES in breast carcinoma progression: regulation of expression and potential mechanisms of promalignant activity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1093–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y, Akamatsu H, Niwa H, Sumi H, Ozaki Y, Abe A. Correlation of tissue and plasma RANTES levels with disease course in patients with breast or cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouh MA, Eissa SA, Zaki SA, El-Maghraby SM, Kadry DY. Importance of serum IL-18 and RANTES as markers for breast carcinoma progression. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieche I, Lerebours F, Tozlu S, Espie M, Marty M, Lidereau R. Molecular profiling of inflammatory breast cancer: identification of a poor-prognosis gene expression signature. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6789–6795. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigler N, Shina S, Kaplan O, Luboshits G, Chaitchik S, Keydar I, et al. Breast carcinoma: a report on the potential usage of the CC chemokine RANTES as a marker for a progressive disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:940–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer G, Schneiderhan-Marra N, Kazmaier C, Hutzel K, Koretz K, Muche R, et al. Prediction of nodal involvement in breast cancer based on multiparametric protein analyses from preoperative core needle biopsies of the primary lesion. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3345–3353. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luboshits G, Shina S, Kaplan O, Engelberg S, Nass D, Lifshitz-Mercer B, et al. Elevated expression of the CC chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) in advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4681–4687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaal-Hahoshen N, Shina S, Leider-Trejo L, Barnea I, Shabtai EL, Azenshtein E, et al. The chemokine CCL5 as a potential prognostic factor predicting disease progression in stage II breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4474–4480. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Yaal-Hahoshen N, Azenshtein E, Shina S, Leider-Trejo L, Ryvo L, et al. Concomitant expression of the chemokines RANTES and MCP-1 in human breast cancer: a basis for tumor-promoting interactions. Cytokine. 2008;44:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Ofri-Shahak M, Haas I, Yaal-Hahoshen N, Leider-Trejo L, Leibovich-Rivkin T, et al. Inflammatory mediators in breast cancer: coordinated expression of TNFalpha & IL-1beta with CCL2 & CCL5 and effects on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Huang R, Chen L, Li S, Shi Q, Jordan C, et al. Identification of interleukin-8 as estrogen receptor-regulated factor involved in breast cancer invasion and angiogenesis by protein arrays. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:507–515. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hively WP, Varmus HE. Use of MMTV-Wnt-1 transgenic mice for studying the genetic basis of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:1002–1009. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin WJ, Jr, Carey LA. What is triple-negative breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2799–2805. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LC, Martyniak A, Kandel MJ, Stadler ZK, Masciari S, Miron A, et al. Basal cytokeratin and epidermal growth factor receptor expression are not predictive of BRCA1 mutation status in women with triple-negative breast cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1093–1097. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31819c1c93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglehart JD, Silver DP. Synthetic lethality—a new direction in cancer-drug development. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:189–191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0903044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FR, Miller BE, Heppner GH. Characterization of metastatic heterogeneity among subpopulations of a single mouse mammary tumor: heterogeneity in phenotypic stability. Invasion Metastasis. 1983;33:22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduction of established spontaneous mammary carcinoma metastases following immunotherapy with major histocompatibility complex class II and B7.1 cell-based tumor vaccines. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1486–1493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Z, Guo H, Wai PY, Gao C, Wei J, Kuo PC. Differential osteopontin expression in phenotypically distinct subclones of murine breast cancer cells mediates metastatic behavior. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46659–46667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslakson CJ, Miller FR. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1399–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecki S, Yacovlev L, Slavin S. Effect of indomethacin on tumorigenicity and immunity induction in a murine model of mammary carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:894–899. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980316)75:6<894::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Grusby MJ, Clements VK. Cutting edge: STAT6-deficient mice have enhanced tumor immunity to primary and metastatic mammary carcinoma. J Immunol. 2000;165:6015–6019. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coveney E, Wheatley GH, 3rd, Lyerly HK. Active immunization using dendritic cells mixed with tumor cells inhibits the growth of primary breast cancer. Surgery. 1997;122:228–234. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhmilevich AL, Janssen K, Hao Z, Sondel PM, Yang NS. Interleukin-12 gene therapy of a weakly immunogenic mouse mammary carcinoma results in reduction of spontaneous lung metastases via a T- cell-independent mechanism. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:826–838. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Cao S, Mitsuhashi M, Xiang Z, Ma X. Genome-wide analysis of molecular changes in IL-12-induced control of mammary carcinoma via IFN-gamma-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2004;172:4111–4122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulaski BA, Clements VK, Pipeling MR, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Immunotherapy with vaccines combining MHC class II/CD80+ tumor cells with interleukin-12 reduces established metastatic disease and stimulates immune effectors and monokine induced by interferon gamma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000;49:34–45. doi: 10.1007/s002620050024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen CR, Klingelhofer J, Tarabykina S, Hulgaard EF, Kramerov D, Lukanidin E. Transcription of a novel mouse semaphorin gene, M-semaH, correlates with the metastatic ability of mouse tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1238–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P, Buxton JA, Acheson A, Radziejewski C, Maisonpierre PC, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Antiangiogenic gene therapy targeting the endothelium-specific receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8829–8834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Mohammad RM, Werdell J, Shekhar PV. p53 and protein kinase C independent induction of growth arrest and apoptosis by bryostatin 1 in a highly metastatic mammary epithelial cell line: in vitro versus in vivo activity. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:915–923. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.6.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecki S, Yacovlev E, Gelfand Y, Trembovler V, Shohami E, Slavin S. Induction of antitumor immunity by indomethacin. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000;48:613–620. doi: 10.1007/s002620050009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler EP, Lemken CA, Katchen NS, Kurt RA. A dual role for tumor-derived chemokine RANTES (CCL5) Immunol Lett. 2003;90:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SC, Scott KA, Wilson JL, Thompson RG, Proudfoot AE, Balkwill FR. A chemokine receptor antagonist inhibits experimental breast tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8360–8365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Ben-Baruch A. The inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and CCL5 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt RA, Baher A, Wisner KP, Tackitt S, Urba WJ. Chemokine receptor desensitization in tumor-bearing mice. Cell Immunol. 2001;207:81–88. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Guan X, Ma X. Interferon regulatory factor 1 is an essential and direct transcriptional activator for interferon γ-induced RANTES/CCl5 expression in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24347–24355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Chow JM, Gri G, Carra G, Gerosa F, Wolf SF, et al. The interleukin 12 p40 gene promoter is primed by interferon gamma in monocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:147–157. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Carvalho G, Fabre C, Grosjean J, Fenaux P, Kroemer G. Targeting NF-kappaB in hematologic malignancies. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:748–758. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Cao S, Herman LM, Ma X. Differential regulation of interleukin (IL)-12 p35 and p40 gene expression and interferon (IFN)-gamma-primed IL-12 production by IFN regulatory factor 1. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1265–1276. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive M, Krylov D, Echlin DR, Gardner K, Taparowsky E, Vinson C. A dominant negative to activation protein-1 (AP1) that abolishes DNA binding and inhibits oncogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18586–18594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammit AJ, Hoffman RK, Amrani Y, Lazaar AL, Hay DW, Torphy TJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced secretion of RANTES and interleukin-6 from human airway smooth-muscle cells. Modulation by cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:794–802. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.6.4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth MP, Twort CH, Lee TH, Hirst SJ. beta2-adrenoceptor agonists inhibit release of eosinophil-activating cytokines from human airway smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:729–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammit AJ, Lazaar AL, Irani C, O'Neill GM, Gordon ND, Amrani Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced secretion of RANTES and interleukin-6 from human airway smooth muscle cells: modulation by glucocorticoids and beta-agonists. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:465–474. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.4.4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S, Olive M, Aggarwal S, Krylov D, Ginty DD, Vinson C. A dominant-negative inhibitor of CREB reveals that it is a general mediator of stimulus-dependent transcription of c-fos. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:967–977. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrowietz U, Schwenk U, Maune S, Bartels J, Kupper M, Fichtner I, et al. The chemokine RANTES is secreted by human melanoma cells and is associated with enhanced tumour formation in nude mice. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1025–1031. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Juremalm M, Olsson N, Backlin C, Sundstrom C, Nilsson K, et al. Expression of CCL5/RANTES by Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells and its possible role in the recruitment of mast cells into lymphomatous tissue. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:197–201. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori N, Krensky AM, Ohshima K, Tomita M, Matsuda T, Ohta T, et al. Elevated expression of CCL5/RANTES in adult T-cell leukemia cells: possible transactivation of the CCL5 gene by human T-cell leukemia virus type I tax. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:548–557. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus RP, Stamp GW, Hadley J, Balkwill FR. Quantitative assessment of the leukocyte infiltrate in ovarian cancer and its relationship to the expression of C–C chemokines. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1723–1734. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Ito F, Nakazawa H, Horita S, Osaka Y, Toma H. High expression of chemokine gene as a favorable prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2004;171:2171–2175. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127726.25609.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaday GG, Peehl DM, Kadam PA, Lawrence DM. Expression of CCL5 (RANTES) and CCR5 in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006;66:124–134. doi: 10.1002/pros.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukishiro S, Suzumori N, Nishikawa H, Arakawa A, Suzumori K. Elevated serum RANTES levels in patients with ovarian cancer correlate with the extent of the disorder. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:542–545. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek S, Bjorck E, Hogerkorp CM, Nordenskjold M, Porwit-MacDonald A, Borrebaeck CA. Mantle cell lymphomas acquire increased expression of CCL4, CCL5 and 4-1BB-L implicated in cell survival. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2092–2097. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran CJ, Arenberg DA, Huang CC, Giordano TJ, Thomas DG, Misek DE, et al. RANTES expression is a predictor of survival in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3803–3812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe MM, Golden JM, Nair P, O'Donnell CM, Werner MT, Kurt RA. Tumor-derived CCL5 does not contribute to breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Verma S, Burra U, Murthy NS, Mohanty NK, Saxena S. Flow cytometric analysis of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in PBMCs as a parameter of immunological dysfunction in patients of superficial transitional cell carcinoma of bladder. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:734–743. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung LP, Rowley DA, Dubey P, Schreiber H. Synergy between T-cell immunity and inhibition of paracrine stimulation causes tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6254–6258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte V, Chappell DB, Apolloni E, Cabrelle A, Wang M, Hwu P, et al. Unopposed production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by tumors inhibits CD8+ T cell responses by dysregulating antigen-presenting cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;162:5728–5737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori S, Martinelli G, Zier K. Resection of solid tumors reverses T cell defects and restores protective immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:2214–2220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, Mamura M, Noben-Trauth N, Donaldson DD, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1741–1752. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danna EA, Sinha P, Gilbert M, Clements VK, Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Surgical removal of primary tumor reverses tumor-induced immunosuppression despite the presence of metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2205–2211. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Ben-Baruch A. The inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and CCL5 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund A, Chauveau C, Brouillet JP, Lucas A, Lacroix M, Licznar A, et al. IL-8 expression and its possible relationship with estrogen-receptor-negative status of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:256–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner JW, Uchida O, Kajiwara N, Kim EY, Patel AC, O'Sullivan MP, et al. CCL5–CCR5 interaction provides antiapoptotic signals for macrophage survival during viral infection. Nat Med. 2005;11:1180–1187. doi: 10.1038/nm1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado FS, Koyama NS, Carregaro V, Ferreira BR, Milanezi CM, Teixeira MM, et al. CCR5 plays a critical role in the development of myocarditis and host protection in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:627–636. doi: 10.1086/427515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LD, Stewart JN, Mead JR. Susceptibility to Cryptosporidium parvum infections in cytokine- and chemokine-receptor knockout mice. J Parasitol. 2002;88:1014–1016. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[1014:STCPII]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algood HM, Flynn JL. CCR5-deficient mice control Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection despite increased pulmonary lymphocytic infiltration. J Immunol. 2004;173:3287–3296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley GA, Smith MW, Allikmets R, et al. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, ALIVE Study. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]