Abstract

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant disease associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. This study aims to examine the effects of EBV infection on the production of proinflammatory cytokines in NPC cells after the Zn-BC-AM photodynamic therapy (PDT) treatment. Cells were treated with the photosensitiser Zn-BC-AM for 24 h before light irradiation. Quantitative ELISA was used to evaluate the production of cytokines. Under the same experimental condition, HK-1-EBV cells produced a higher basal level of IL-1α (1561 pg/ml), IL-1β (16.6 pg/ml) and IL-8 (422.9 pg/ml) than the HK-1 cells. At the light dose of 0.25–0.5 J/cm2, Zn-BC-AM PDT-treated HK-1-EBV cells were found to produce a higher level of IL-1α and IL-1β than the HK-1 cells. The production of IL-1β appeared to be mediated via the IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE)-independent pathway. In contrast, the production of angiogenic IL-8 was downregulated in both HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells after Zn-BC-AM PDT. Our results suggest that Zn-BC-AM PDT might indirectly reduce tumour growth through the modulation of cytokine production.

Keywords: Photodynamic therapy, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, cytokines, Epstein-Barr virus

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been developed as a method for both cancer and non-cancer treatments. The process of tumour-cell killing involves the activation of photosensitiser by light with an appropriate wavelength of light. PDT-mediated tumour eradication may be achieved by direct killing of tumour cells and/or the induction of indirect ischemic cell death due to the collapse of surrounding tumour vasculature. Previous studies showed that cytokines could be released by the PDT-treated tumours.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The tumour-derived cytokines may attract the migration of neutrophils and phagocytes to the tumour bed and eliminate the cell debris caused by PDT. Macrophages can be also activated to destroy the remaining tumour cells and to prevent distant metastasis.6, 7 Thus, PDT may also control the growth of tumour via the modulation of the antitumour immunity.

The development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is known to be associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. Recent studies also showed that the production of cytokines in NPC cells could be modulated by EBV.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 However, the effect of PDT on the production of proinflammatory cytokines by EBV-infected NPC cells has not been examined. In this study, we found that Zn-BC-AM PDT differentially modulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines in both EBV-negative and -positive HK-1 cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Antibodies against caspase-1 (IL-1β-converting enzyme, ICE) and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Stock solution of the photosensitiser, Zn-BC-AM,14 was prepared in dimethylsulphoxide.

Cell culture

HK-1 cells15 and HK-1-EBV cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and antibiotics penicillin (50 µg/ml)/ streptomycin (50 µg/ml) (Gibco). HK-1 cells with persistent EBV latent infection (HK-1-EBV cells) were established as previously described.11 The resultant HK-1-EBV cells carried a neomycin-resistance (neor) gene and an enhanced green fluorescent protein gene. The presence of enhanced green fluorescent protein would facilitate the subsequent monitoring of the infected HK-1 cells. The cells were cultivated in medium supplemented with 400 µg/ml of G418. The cells were maintained and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Zn-BC-AM PDT treatment

HK-1 cells and HK-1-EBV cells were incubated overnight in 35 mm Petri dish. Zn-BC-AM (2 µM) was then added and the cells were incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 24 h. Medium containing Zn-BC-AM was replaced with fresh medium before light irradiation. NPC cells were irradiated by light at an intensity of 0.8 mW/cm2 from a projector equipped with a 400-W tungsten lamp, a heat-isolation filter and a narrow band filter (682±5 nm). After light irradiation, the cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C until further investigation.

Propidium iodide (PI) exclusion assay

Both adherent and floating cells were collected at 24 h post PDT. The cells were then incubated with PI (5 µg/ml in phosphate buffered saline) in dark for 5 min. The cells were then immediately analysed by FACSCalibur (Becton Dickson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with the excitation wavelength at 488 nm. Fluorescent signals were collected by the FL-2 channel. Data were further analysed by the CellQuest software.

Western blot

PDT-treated cells were lysed with lysis buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1% NP-40 and 150 mM NaCl). Cellular extracts (20-30 µg protein) were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membrane. The membrane was probed with primary antibodies and the specific antibody-labelled proteins were detected by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) and the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc., Shelton, CT, USA).

Determination of cytokine production by ELISA method

Culture supernatant was collected at 24 h after PDT treatment. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The culture supernatant was then collected for the detection of human cytokines using ELISA kits (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

All graphs were plotted and analysed by the softwares Microsoft Excel, SigmaPlot and SPSS. Statistical significance (P<0.05) was determined using Student's t-test.

Results

Effects of Zn-BC-AM PDT on the growth of HK-1-EBV cells

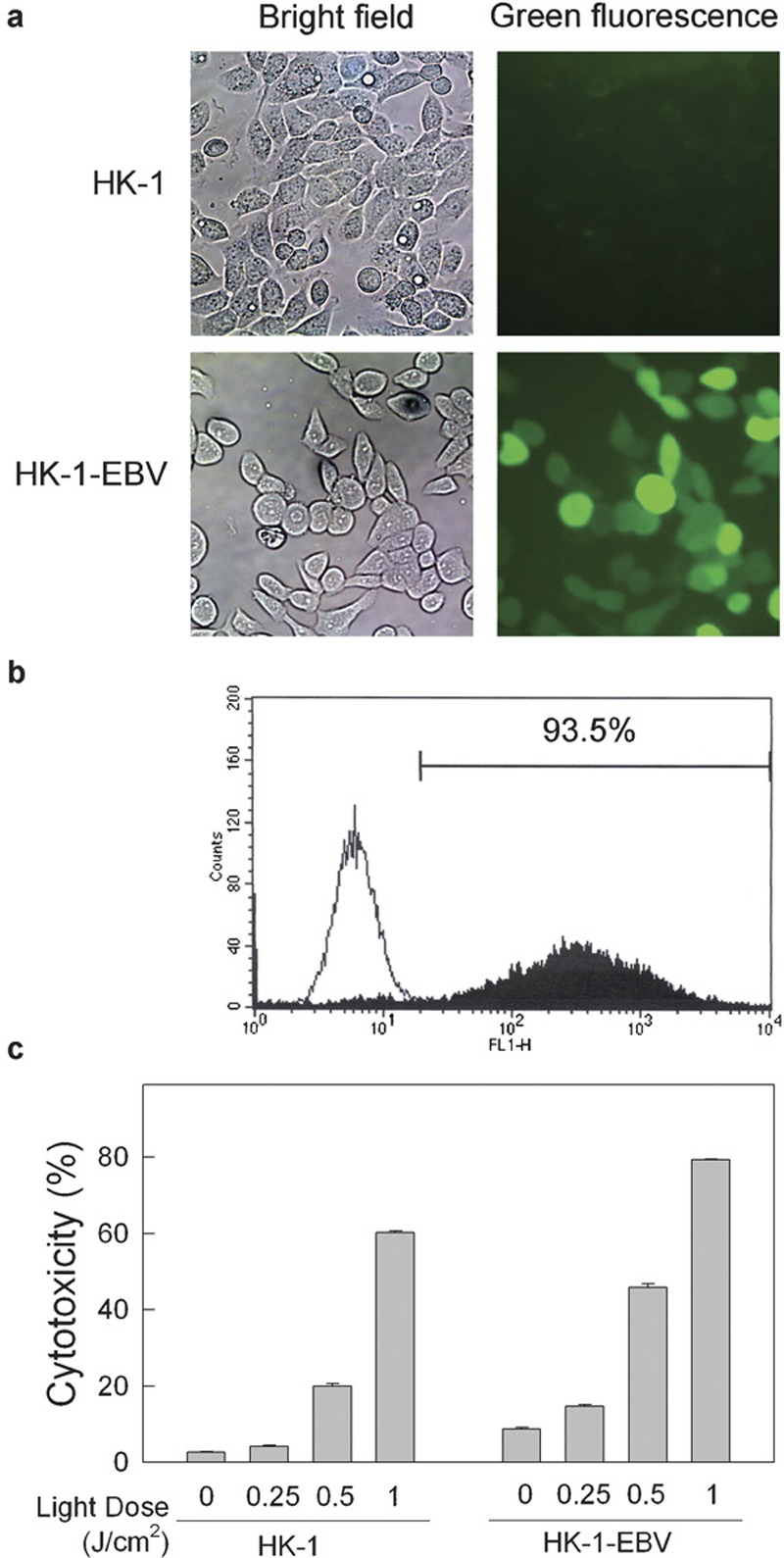

HK-1-EBV cells are the HK-1 cells with stable EBV infection. This cell line contains a recombinant EBV carrying a neomycin-resistance gene and an enhanced green fluorescent protein gene.11 Before the investigation, HK-1-EBV cells were firstly checked for the presence of EBV infection. Green fluorescent signals were detected in HK-1-EBV cells (Figure 1a). Flow cytometric analysis was also used to quantitatively determine the percentage of cells showing infection. Over 93% of HK-1-EBV, as judged from the presence of green fluorescent signal, was positive for EBV (Figure 1b). Zn-BC-AM PDT effectively induced cell death in both HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells in a light-dose-dependent manner (Figure 1c). To avoid excessive cell death induced by PDT, the light dose of 0.25–0.5 J/cm2 was selected for the subsequent studies for cytokine production.

Figure 1.

Effect of Zn-BC-AM PDT-induced cell death in HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells. (a) Fluorescence and bright field images of HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cell lines were captured by fluorescence microscope. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of green fluorescence intensity in HK-1 cells (—) and HK-1-EBV cells (▪). (c) HK-1 cells (3×105) or HK-1-EBV cells (4.5×105) in 35 mm Petri dish were grown overnight and then incubated with Zn-BC-AM (2 µM) for 24 h. Medium containing Zn-BC-AM was then replaced with fresh medium before light irradiation. The cells were irradiated at a light dose of 0.25–1 J/cm2. Both adherent and floating cells were collected at 24 h after PDT. The cells were then incubated with PI (5 µg/ml) in dark for 5 min and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. PI fluorescence signals were collected by the FL-2 channel. Data were analysed by the CellQuest software. Results were expressed as mean±SD of three replicates of each treatment. EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PI, propidium iodide.

Effects of Zn-BC-AM PDT on the production of IL-1 in HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells

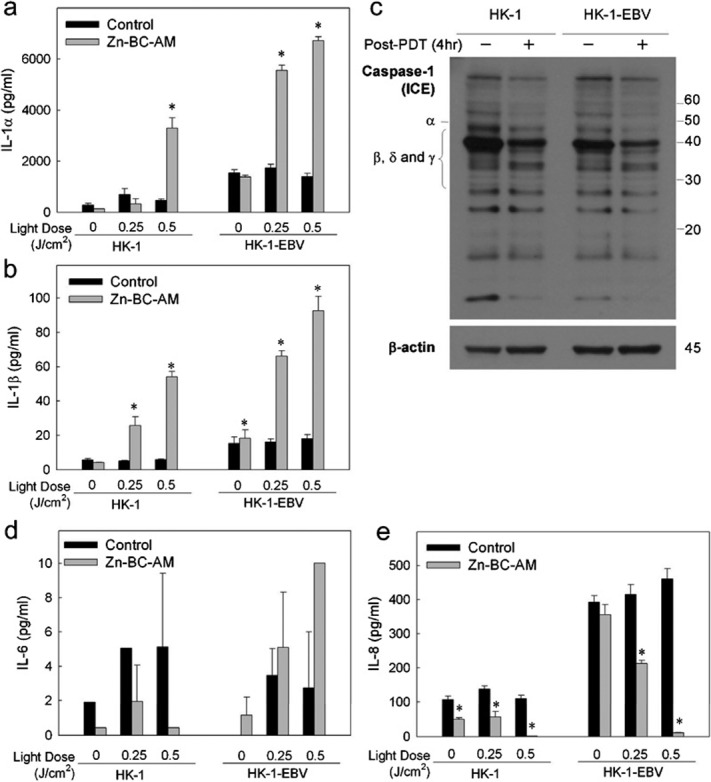

At a light dose of 0.5 J/cm2, the level of IL-1α in HK-1 cell culture supernatant was significantly increased to 3301 pg/ml, a level 12-fold higher than the basal level of IL-1α in the cell control group (282 pg/ml). For the HK-1-EBV cells, light irradiation alone (0.25 or 0.5 J/cm2) had no effect on the production of IL-1α. However, about a 3.5- to 4-fold increase in the level of IL-1α was seen in Zn-BC-AM PDT-treated HK-1-EBV cells. The pattern of PDT-induced IL-1β production was also similar to IL-1α. Zn-BC-AM PDT induced an approximately 4- to 9-fold increase in IL-1β by PDT-treated HK-1 cells. For the HK-1-EBV cells, the level of IL-1β production was increased from 18 pg/ml in the cell control group to 92 pg/ml (0.5 J/cm2) after PDT. It is worthy to note that the total levels of IL-1α and IL-1β in the PDT-treated HK-1-EBV culture supernatant were higher than in the HK-1 cells.

Next, we determined whether the increase in the production of IL-1β was due to the activation of ICE after PDT. ICE consists of several isoforms due to alternative splicing of the gene. Functional ICE is in the form of tetramer containing two p20 and two p10 subunits.16 From the Western blot results, although the ICE isoforms were detected after PDT, the expression of p20 products was not detected in cells before or after Zn-BC-AM PDT (Figure 2c). The results suggested that ICE activation is probably not involved in the PDT-induced production of IL-1β in HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells.

Figure 2.

Production of cytokines in Zn-BC-AM PDT-treated HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells. HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells were treated with Zn-BC-AM (2 µM) for 24 h. The cells were then irradiated with various light doses. Culture medium was collected at 24 h after PDT and the levels of IL-1 were determined by ELISA. The amounts of IL-1α (a), IL-1β (b), IL-6 (d) and IL-8 (e) produced were compared to untreated HK-1 control cells. *P<0.05 versus corresponding cell controls. (c) Western blotting analysis of IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE)/caspase-1 in PDT-treated HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells. HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells were treated with Zn-BC-AM or Zn-BC-AM PDT as described in the section on ‘Materials and methods'. The expression of ICE (or caspase-1) was analysed at 4 h after Zn-BC-AM PDT by Western blot. EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; PDT, photodynamic therapy.

Detection of IL-6 production in HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells

In addition to IL-1, we also measured the production of IL-6 in cells after PDT. Although a trace amount of IL-6 was detected in the HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells (Figure 2d), the concentration was beyond the detection limit of the ELISA kit (<6 pg/ml). This finding indicates that IL-6 is probably not the major cytokine modulated by Zn-BC-AM PDT.

Inhibition of IL-8 production by Zn-BC-AM PDT

IL-8 is a well-known chemotactic cytokine for neutrophils. In the present study, we found that Zn-BC-AM alone slightly reduced the production of IL-8 in HK-1 cells but not in HK-1-EBV cells (Figure 2e). Zn-BC-AM PDT (0.5 J/cm2) almost completely suppressed IL-8 production by HK-1 cells. For the HK-1-EBV cells, a higher basal level of IL-8 production was seen in this cell line. This result is consistent with the recent study that EBV viral proteins could increase the expression of IL-8. Here, we further found that the level of IL-8 production could significantly be suppressed after PDT.

Discussion

In the past decades, PDT was developed as an alternative method for the treatment of malignant and non-malignant diseases. The antitumour mechanisms include (i) photoactivation of the photosensitisers and the subsequent direct killing of the tumour cells; (ii) destruction of vascular bed in the tumour mass and (iii) modulation of the immune reactions.17 Unlike other cancers, NPC is a malignant disease associated with EBV infection. It is generally believed that EBV plays a role in the development of the NPC tumour.11 Although PDT had been shown to induce inflammatory cytokines in PDT-treated tumour cells,18, 19 the effects of PDT on the production of inflammatory cytokines in EBV-harboured tumour cells was not studied. In the present study, we compared the production of proinflammatory cytokines by the NPC cells with or without EBV infection. IL-1 (IL-1α and IL-1β) is a well-known cytokine which can not only regulate inflammatory response, but also mediate the antiproliferative effect on tumour cells.20, 21 In the present study, PDT significantly increases the production of IL-1 in HK-1-EBV cells. This finding suggested that PDT-induced IL-1 may exert an antitumour immunity through the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the reduction of tumour growth. Although both IL-1α and IL-1β mediate similar biological functions, proteolytic cleavage of pro-IL-1β is required for the production of functional IL-1β. The maturation process may be mediated via the ICE-dependent or ICE-independent pathway. In the PDT-treated HK-1 and HK-1-EBV cells, the lack of a detectable level of p10 and p20 subunits of ICE suggested that the ICE-dependent pathway is probably not the major pathway involved in the production of IL-1β.

In addition to the chemotactic function, IL-8 has also been shown to mediate angiogenic function in NPC.22 In addition, EBV infection was found to modulate the production of IL-8 in the undifferentiated NPC cells.12 We further extend the observation that the basal expression level of IL-8 could be increased in the well-differentiated NPC cells. Du and co-workers found that the production of IL-8 in NPC cells was increased after hypericin-PDT.23 In the present study, we found that Zn-BC-AM PDT suppressed the production of IL-8 in both infected and uninfected NPC cells. The discrepancy of IL-8 production may be photosensitiser-dependent. Taken together, the capability of Zn-BC-AM PDT to increase the production of IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-6, and to suppress the production of angiogenic IL-8 in EBV-infected NPC warrants the further development of Zn-BC-AM PDT for the treatment of NPC. In conclusion, this preliminary in vitro study examined the influence of EBV infection on the production of inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-8 by PDT-treated NPC cells. In addition to the cytotoxic action on the tumour cells, Zn-BC-AM PDT may modulate the immune response through the elevation of IL-1 production and suppress EBV-induced IL-8 production.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (HKBU2052/02M and HKBU2458/06M).

References

- Gollnick SO, Evans SS, Baumann H, Owczarczak B, Maier P, Vaughan L, et al. Role of cytokines in photodynamic therapy-induced local and systemic inflammation. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1772–1779. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrer S, Bosserhoff AK, Weiderer P, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Keratinocyte-derived cytokines after photodynamic therapy and their paracrine induction of matrix metalloproteinases in fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Oseroff AR, Baumann H. Photodynamic therapy causes cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins and attenuation of interleukin-6 cytokine responsiveness in epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6579–6587. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nseyo UO, Whalen RK, Duncan MR, Berman B, Lundahl SL. Urinary cytokines following photodynamic therapy for bladder cancer. A preliminary report. Urology. 1990;36:167–171. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(90)80220-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TW, Tracy E, Oseroff AR, Baumann H. Photodynamic therapy mediates immediate loss of cellular responsiveness to cytokines and growth factors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3812–3818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hady ES, Martin-Hirsch P, Duggan-Keen M, Stern PL, Moore JV, Corbitt G, et al. Immunological and viral factors associated with the response of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia to photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler K, Unanue ER. Identification of a macrophage antigen-processing event required for I-region-restricted antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1981;127:1869–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busson P, Braham K, Ganem G, Thomas F, Grausz D, Lipinski M, et al. Epstein–Barr virus-containing epithelial cells from nasopharyngeal carcinoma produce interleukin 1 alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6262–6266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Pazolt D, Grabenbauer GG, Nicholls JM, Herbst H, Young LS, et al. Expression of cytokine and chemokine genes in Epstein–Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: comparison with Hodgkin's disease. J Pathol. 2001;194:145–151. doi: 10.1002/path.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CT, Kao HJ, Lin JL, Chan WY, Wu HC, Liang ST. Response of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to Epstein–Barr virus infection in vitro. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1149–1160. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo AK, Lo KW, Tsao SW, Wong HL, Hui JW, To KF, et al. Epstein–Barr virus infection alters cellular signal cascades in human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8:173–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.05625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M, Wu SY, Chang SS, Su IJ, Tsai CH, Lai SJ, et al. Epstein–Barr virus lytic transactivator Zta enhances chemotactic activity through induction of interleukin-8 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. J Virol. 2008;82:3679–3688. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02301-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Sheen TS, Chen CL, Lu J, Chang Y, Chen JY, et al. Profile of cytokine expression in nasopharyngeal carcinomas: a distinct expression of interleukin 1 in tumor and CD4+ T cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1599–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak NK, Li KM, Leung WN, Wong RN, Huang DP, Lung ML, et al. Involvement of both endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in photokilling of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by the photosensitizer Zn-BC-AM. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:2387–2396. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DP, Ho JH, Poon YF, Chew EC, Saw D, Lui M, et al. Establishment of a cell line (NPC/HK1) from a differentiated squamous carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Int J Cancer. 1980;26:127–132. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocci MJ. Structure and function of interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Vitam Horm. 1997;53:27–63. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak NK, Lung ML, Chang CK, Leung KN.Photosensitizers as novel compounds in apoptosis researchIn: Corvin AJ (ed.)New Developments in Cell Apoptosis Research New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.2006, 241–272. [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Bay BH, Mahendran R, Olivo M. Hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy elicits differential interleukin-6 response in nasopharyngeal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005;235:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li KM, Sun X, Koon HK, Leung WN, Fung MC, Wong RNS, et al. Apoptosis and expression of cytokines triggered by pyropheophorbide-a methyl ester-mediated photodynamic therapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2006;3:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunschweiger PG, Basrur VS, Santos O, Markoe AM, Houdek PV, Schwade JG. Synergistic antitumor activity of cisplatin and interleukin 1 in sensitive and resistant solid tumors. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1091–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian PL, Kaffka KL, Biondi DA, Lipman JM, Benjamin WR, Feldman D, et al. Antiproliferative effect of interleukin-1 on human ovarian carcinoma cell line (NIH:OVCAR-3) Cancer Res. 1991;51:1823–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki T, Horikawa T, Qing-Chun R, Wakisaka N, Takeshita H, Sheen TS, et al. Induction of interleukin-8 by Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 and its correlation to angiogenesis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1946–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Bay BH, Mahendran R, Olivo M. Endogenous expression of interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and the effect of photodynamic therapy. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]