Abstract

The region of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome between the UL127 promoter and the major immediate-early (MIE) enhancer is referred to as the unique region. The role of this region during a viral infection is not known. In wild-type HCMV-infected permissive fibroblasts, there is no transcription from the UL127 promoter at any time during productive infection. Our investigators previously reported that the region upstream of the UL127 TATA box repressed expression from the UL127 promoter (C. A. Lundquist et al., J. Virol. 73:9039-9052, 1999). The region was reported to contain functional NF1 DNA binding sites (L. Hennighausen and B. Fleckenstein, EMBO J. 5:1367-1371, 1986). Sequence analysis of this region detected additional consensus binding sites for three transcriptional regulatory proteins, FoxA (HNF-3), suppressor of Hairy wing, and CAAT displacement protein. The cis-acting elements in the unique region prevented activation of the early UL127 promoter by the HCMV MIE proteins. In contrast, deletion of the region permitted very high activation of the UL127 promoter by the viral MIE proteins. Mutation of the NF1 sites had no effect on the basal activity of the promoter. To determine the role of the other sites in the context of the viral genome, recombinant viruses were generated in which each putative repressor site was mutated and the effect on the UL127 promoter was analyzed. Mutation of the putative Fox-like site resulted in a significant increase in expression from the viral early UL127 promoter. Insertion of wild-type Fox-like sites between the HCMV immediate-early (IE) US3 TATA box and the upstream NF-κB-responsive enhancer (R2) also significantly decreased gene expression, but mutated Fox-like sites did not. The wild-type Fox-like site inhibits activation of a viral IE enhancer-containing promoter. Cellular protein, which is present in uninfected or infected permissive cell nuclear extracts, binds to the wild-type Fox-like site but not to mutated sites. Reasons for repression of UL127 gene transcription during productive infection are discussed.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replicates in various terminally differentiated cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, smooth muscle, fibroblast, macrophage, trophoblast, and microglial cells (38, 54, 57). HCMV contains a linear double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 230 kbp that can code for more than 220 proteins (8). The viral genes are expressed in three temporal phases referred to as immediate-early (IE), early, and late. Transcription of the IE genes is independent of any de novo viral protein synthesis. The highest amount of transcription at IE times after infection occurs from the major IE (MIE) locus (60). Spliced mRNAs from the IE1 (UL123) and IE2 (UL122) genes transcribed from the MIE promoter code for two well-characterized proteins, IE72 and IE86, respectively, plus several isomers (59, 60). The IE1 gene is necessary for efficient replication at low multiplicity of infection (MOI) but dispensable for growth at high MOI (20, 44). The IE2 gene is essential for early viral gene expression (40). The IE86 protein is a strong transactivator of both viral and cellular gene expression (5, 21, 25, 28, 30, 34, 34a, 59, 60). Early gene expression is required for viral DNA replication, which then results in expression of the late genes. The late genes encode structural proteins required for virion maturation.

The MIE enhancer and the flanking regions were assigned arbitrary boundaries (43, 61). Downstream of the +1 start site is a positive regulatory control region from +8 to +112, referred to as leader exon 1 (16). The MIE promoter between −50 and +8 contains a TATA box, a cis-repression sequence (crs) between −13 and −1, and an initiator-like sequence between +1 and +7 (36, 37, 43, 61). The IE86 protein negatively autoregulates the MIE promoter by binding to the crs (9, 33, 51). The IE86 protein interferes with the binding of a 150-kDa cellular transcription initiation factor and represses RNA polymerase II initiation at the MIE promoter (32, 36, 37, 65). The very strong MIE enhancer between −550 and −50 contains multiple transcription factor binding sites, including sites for cellular NF-κB/rel, CREB/ATF, AP1, YY1, SP-1, RAR-RXR, and serum response factor (43, 61). These cis-acting elements respond to a variety of signal transduction events early after infection and stimulate transcription from the MIE promoter (2, 7, 43, 61). Upstream of the enhancer between −750 and −550 is a region referred to as the unique region (15, 43, 61). The role of the unique region in viral replication or latency is not understood. The unique region contains NF1 binding sites, but to date no function has been assigned to these sites (23). Deletion of the modulator region between −1108 and −750, which contains the UL127 open reading frame (ORF), had no effect on transcription from the MIE promoter upon infection in either undifferentiated or differentiated cells (42). UL127 is conserved in all HCMVs sequenced to date, and the nucleotide sequence is 61% identical to chimpanzee CMV (7, 11, 13, 45). In HCMV, the region contains a 939-bp ORF. A TATA box sequence, which is identical in DNA sequence to that of the MIE promoter, is positioned 38 bp upstream of the UL127 ORF and is transcriptionally divergent from the MIE promoter and genes (8). Since the transcription start site from the UL127 promoter had not been mapped, the region of the viral genome between the UL127 promoter and the MIE promoter was designated relative to the transcription start site (+1) of the MIE promoter as described previously (35). Although UL127 may be important for either viral latency or pathogenesis, it is not essential for replication in human fibroblast cells in culture (42). Northern blotting and viral DNA microarray analyses did not detect transcription from UL127 at any time after infection in cell culture (6, 35). In contrast, high expression from the UL127 promoter was observed when the UL127 ORF was replaced by a reporter gene and the unique region upstream of the TATA box was deleted or replaced (1, 35).

We hypothesized that a cellular protein(s) inhibits transcription from the UL127 promoter. Analysis of the sequence between −694 and −640 using the Transfac database identified several cis sites for the binding of known transcriptional repressor proteins (22). Immediately upstream of the UL127 TATA box (−691 to −681) is a consensus binding site for members of the forkhead box (Fox) family of transcriptional regulatory proteins. Fox proteins, including FoxA (HNF-3), Foxq1 (HFH-1), and Foxd3 (HFH-2 or genesis), share homology to the Drosophila melanogaster homeotic protein forkhead (fkh) and contain a DNA binding domain termed winged helix. The Fox proteins have been characterized mainly from the liver, but these cellular proteins are also expressed in other tissues, including the brain, kidney, lung, intestine, bladder, stomach, and salivary gland (3, 10). Fox sites are involved in both activation and repression of gene expression (26, 53, 63). Two NF1 binding sites are located in this region. The NF1 DNA binding protein family has been implicated in both positive and negative regulation of cellular and viral promoters (14, 27, 48, 49). Further upstream of the UL127 TATA box (from −670 to −659) is a consensus binding site for the Drosophila protein suppressor of Hairy wing [su(Hw)] (58). In Drosophila the su(Hw) binding site acts as an insulator between an enhancer and a divergent promoter when bound by the su(Hw) protein (55). However, a functional su(Hw) protein has not been reported in mammals. Most distal to the UL127 TATA box (−650 to −642 and −635 to −627) is a pair of CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) binding sites (46). In transient-transfection experiments, two of these DNA elements located between the human papillomavirus type 16 enhancer and E6/E7 promoter repress transcription from the E6/E7 promoter (47).

In this report, we show that site-specific mutation of the Fox-like binding site upstream of the UL127 promoter allowed for significant gene transcription at early and late times after infection. The wild-type sequences in this region inhibited activation of the UL127 promoter by the viral IE proteins. In addition, the wild-type Fox-like binding site, when placed between the HCMV R2 enhancer and the IE US3 promoter, inhibited downstream IE US3 transcription. Reasons for a strong cellular repressor element upstream of the HCMV UL127 promoter that inhibits transcription at all times after viral infection of permissive human fibroblast cells are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) and Lesch-Nyhan fibroblasts (GM02291; Coriell Cell Repositories, Camden, N.J.) were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Mediatec, Herndon, Va.) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Enzymes.

Restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). T4 DNA ligase, Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I, and shrimp intestinal phosphatase were obtained from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, Ind.). T7 RNA polymerase was obtained from Promega (Madison, Wis.). All enzymes were used according to the manufacturers' specifications.

CAT assay.

All transfections or infections with recombinant viruses were performed in triplicate on 100-mm-diameter plates of HFF or HeLa cells. Plasmid pCL3+ was generated by digestion of pLC3+ with restriction endonuclease HindIII and religation in the reverse orientation (36). This results in the UL127 promoter driving the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene. pCL dl−694/−583 was generated in the same way from plasmid pLC dl−694/−583. Transfections were preformed by calcium phosphate precipitation or with FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). For transfections, 2 μg of each expression plasmid was used. CAT enzyme activities were determined in substrate excess as described by Gorman et al. (17). The acetylated and unacetylated [14C]chloramphenicol (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.) was separated by thin-layer chromatography in a chloroform-methanol (95:5) solvent. The amount of [14C]chloramphenicol acetylation was determined by image acquisition analysis on a Packard Instant Imager (Packard Instrument Co., Meriden, Conn.), and the protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.).

LUX assay.

Luciferase (LUX) assays were performed by the method of De Wet et al. (12). Luminescence was detected in an Anthos Lucy 1 luminometer (Salzburg, Austria). The mean LUX units per microgram of protein lysate were determined. Plasmids pLC3+ and pLC dl−694/−583 have been described previously (35, 39). Plasmid LC3+NF1 mut−684/−628 containing mutations in the NF1 sites was constructed by two successive rounds of mutagenesis with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) with pLC3+ as the template. The primers used in round one were 5′-AATAggcGCTATTGGaacTTGCATACG-3′ and 5′-CAATAGCgccTATTGATTTATGC-3′. The primers used in round two were 5′-TATAggcGCTCATGTaCcAcATtACCG-3′ and 5′-GACATGAGCgccTATAAATGTACA-3′. Mutations are given in lowercase. The mutations designated the 5′ end location as either −684 or −628 (see Fig. 2).

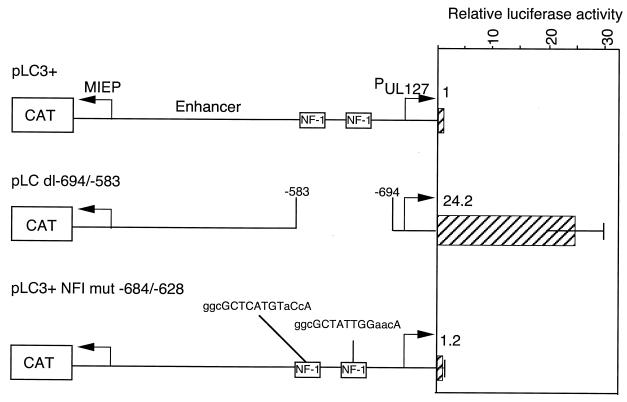

FIG. 2.

Effect of mutation of the NF1 sites on the basal activity of the UL127 promoter upstream of the LUX gene. HFF cells were transfected in triplicate with either plasmid pLC3+, pLC dl−694/−583, or pLC3+ NF1mut−684/−628. The mean LUX activity and standard deviation were determined per microgram of protein lysate relative to the activity with plasmid pLC3+, as described in Materials and Methods. CAT activity validated equivalent transfection efficiency.

Shuttle vectors for recombination.

Shuttle vectors pdlMCAT Fox−a, pdlMCAT Fox−b, pdlMCAT su(Hw)−, and pdlMCAT CDP− were constructed from pdlMCAT (35). Mutations in the Fox, su(Hw), and CDP sites were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with complementary primer pairs, where one primer of the pair had the sequence 5′-GCCAATAGCCAActggaccTTATGCTATATAACCAAGCTT-3′, 5′-GCCAATAGCCAAgccgtggTTATGCTATATAACCAAGCTT-3, 5′-TAGATACAACcatccacATGGCCAATAGCCAATATTGATTTATGC-3′, or 5′-GGACATGAGCCgctctgacTGTACATtgaagagTATAGATACAACG-3′. The resulting plasmids were named pdlMCAT Fox−a, pdlMCAT Fox−b, pdlMCAT su(Hw)−, and pdlMCAT CDP−. Mismatch mutations are given as lowercase, and the nucleotides corresponding to the location of the consensus binding site are underlined.

The sequence between −694 and −640 was reversed by generating a new BsrGI restriction endonuclease site at −694 with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with complementary primer pairs, where one primer of the pair had the sequence 5′-CAATAGCCAATATTGATTTgTacaTATATAACCAAGCTTGCGATC-3′. After digestion with BsrGI, the sequence between the new BsrGI site (−694) and the endogenous BsrGI site (−640) was reversed and ligated to generate the shuttle vector pdlMCAT −694/−640R. We introduced an SpeI restriction site at position −694 using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with complementary primer pairs, where one primer of the pair had the sequence 5′-CAATAGCCAATATTGATTTActagTATATAACCAAGCTTGCGATC-3′. After digestion with SpeI, the sequence between the new SpeI site (−694) and the endogenous SpeI site (−583) was ligated in the reverse orientation to generate the shuttle vector pdlMCAT −694/−583R.

Shuttle vectors were also constructed from pR1R2crs-CAT (31). Three repeats of the wild-type Fox-binding site from either the UL127 promoter, mutant Fox−a, or mutant Fox−b were inserted in the sense orientation using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with complementary primer pairs, where one primer of the pair had the sequence 5′-GGGAAACAACGTCACCAAGAACAATATTGATTTCAATATTGATTTCAATATTGATTTACGCTATATATTCAAAAACAAGCCTACCCGGCC-3′, 5′-GGGAAACAACGTCACCAAGAACAActggaccTTCAActggaccTTCAActggaccTTACGCTATATATTCAAAAACAAGCCTACCCGGCC-3′, and 5′-GGGAAACAACGTCACCAAGAACAAgccgtggTTCAAgccgtggTTCAAgccgtggTTACGCTATATATTCAAAAACAAGCCTACCCGGCC-3′, respectively. The resulting shuttle vectors were named pUS3 Fox(wt) CAT, pUS3 Fox−a CAT, and pUS3 Fox−b CAT, respectively. All mutations were confirmed by automated dideoxynucleotide sequencing (University of Iowa DNA Core Facility).

Recombinant virus isolation.

Parental HCMV recombinant viruses RVdlMSVgpt and RVgptR2crs-CAT have been described previously (31, 35). RVdlMCAT wt, containing the wild-type UL127 promoter driving expression of the CAT gene, was described previously (35).

According to the method of Greaves et al. (19), shuttle vectors (5 or 10 μg) were cotransfected into HFFs with either RVdlMSVgpt or RVgptR2crs-CAT viral DNA by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (18). After homologous recombination, recombinant viruses were selectively grown and plaque purified using hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase-deficient Lesch-Nyhan fibroblasts (Coriell Cell Repositories) in medium containing 6-thioguanine (Sigma) at 50 μg/ml. Viral plaques were transferred to HFF cells, and recombinant viruses were detected by dot blot hybridization with either a 32P-labeled CAT-specific (301-bp NcoI/EcoRI fragment of the CAT ORF) or 32P-labeled US7-specific (1,205-bp BamHI/HindIII fragment of the US7 ORF) DNA probe. Viruses giving positive hybridization were plaque purified a second time in HFF cells.

Southern blot hybridizations.

Viral DNA was isolated from the virions as described previously (62) and digested with the appropriate restriction endonucleases before being subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blot hybridization as described previously (42). A [32P]CAT probe was prepared using Ready-To-Go DNA labeling beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.).

RNase protection assay.

Antisense riboprobe synthesis was by the method of Krieg and Melton as described previously (29). Construction of the plasmid DNA template and the antisense IE1 riboprobe was described previously (24). pUS3-5′CAT was generated when the SnaBI/EcoRI fragment of p7R15R2CAT (64) was inserted into the HincII and EcoRI sites of pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene). Antisense US3/CAT riboprobe was synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase and plasmid pUS3-5′CAT linearized with XhoI. p127CAT, which contains the UL127 promoter to position −583 and the 5′ end of the CAT ORF, was generated when the SpeI (blunted with Klenow)-PvuII fragment of pdlMCAT (35) was inserted into the SmaI site of pGEM-4Z (Promega). Antisense UL127/CAT riboprobe was synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase and plasmid p127CAT linearized with BsrGI. Twenty micrograms of cytoplasmic RNA, harvested from uninfected and infected HFFs, was hybridized to the 32P-labeled riboprobes at 25°C overnight as described previously (35). The RNAs protected from RNase T1 digestion were fractionated in 6% polyacrylamide-urea gels. The signals were visualized by autoradiography on Hyperfilm-MP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

EMSAs.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as described previously (4, 50). The oligonucleotide 5′-GAATT(CAATATTGATTT)3TCTAGAGGG-3′ was annealed to a complementary oligonucleotide, digested with restriction endonucleases EcoRI I and XbaI, and ligated into the same sites of plasmid pHISi (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) to generate the plasmid pHISi-Fox(wt). pHISi-Fox−a and pHISi-Fox−b were generated in the same manner with oligonucleotide pairs, of which one oligonucleotide had the sequence 5′-GAATT(CAActggaccTT)3TCTAGAGGG-3′ and 5′-GAATT(CAAgccgtggTT)3TCTAGAGGG-3′, respectively. Mutations of the Fox-like site are given as lowercase letters. Double-stranded DNA for use as radiolabeled probe or nonradioactive competitor was generated by PCR from pHISi-Fox(wt), pHISi-Fox−a, or pHISi-Fox−b as the template and primers 5′-CCTCTTCGCTATTACGCCAG-3′ and 5′-GGGCTTTCTGCTCTGTCATC-3′, followed by digestion with the restriction endonuclease Tsp509 I. The 46-bp digestion product was isolated by electrophoresis through a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Concentrations of the DNA fragments were estimated by the ethidium dot assay (52). Radioactive probe was labeled by filling the overhang left from the Tsp509 I digestion of the Fox(wt) PCR product with Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I (New England Biolabs) in the presence of [32P]dATP (Amersham). A Nuctrap column (Stratagene) removed unincorporated deoxynucleotide triphosphates. A 20-μl binding reaction mixture was performed in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, containing 40 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 5% glycerol with 4 μg of denatured sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 4 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC) (Amersham), 4 μg of HeLa cell nuclear extract, or 20 μg of uninfected or infected HFF cell nuclear extract at 25°C for 10 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (65). Nonradioactive competitor DNAs at 25-, 50-, or 100-fold molar excess relative to approximately 3 fmol of labeled DNA probe were added and incubated at 25°C for 15 min. DNA-protein complexes were separated from free probe by electrophoresis in a 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.25× TBE (22.25 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.3, containing 0.5 mM EDTA). The effect of antibody on DNA-protein complexes was determined by adding 1 or 2 μl of normal rabbit serum, anti-Foxa1 (HNF-3α), or anti-Foxa2 (HNF-3β), which were gifts from Robert Costa, University of Illinois, Chicago. After 25°C for 15 min, 3 fmol of probe was added. After 25°C for 15 min, the DNA-protein complexes were separated by electrophoresis as described above. Gels were dried and exposed to Hyperfilm-MP (Amersham).

RESULTS

The unique region represses the UL127 promoter activation by the HCMV MIE proteins.

Our investigators have previously reported that the UL127 promoter is an early viral promoter when the unique region is deleted in the viral genome (35). We examined the mechanism by which the UL127 promoter is regulated. The effects of the HCMV IE1 and IE2 gene products were tested, because the viral proteins are known to strongly activate early viral promoters (25). HeLa cells were cotransfected in triplicate with the UL127 promoter reporter plasmids containing or lacking the unique region as well as an effector plasmid, pSVCS, that expresses HCMV IE1 and IE2 gene products. The CAT reporter plasmid pCL3+ contains wild-type unique region upstream of the UL127 promoter, whereas plasmid pCL dl−694/−583 differs only by having a deletion of the unique region between −694 and −583. The LUX gene was downstream of the MIE promoter. The viral IE gene products had little to no effect on the UL127 promoter in plasmid pCL3+. In contrast, CAT expression from the UL127 promoter increased 48-fold when the sequences between −694 and −583 were deleted (Fig. 1). These data suggest that the unique region contains one or more elements that repress HCMV MIE protein-dependent expression from the early UL127 promoter.

FIG. 1.

Effect of HCMV IE1 and IE2 gene products on CAT expression from the viral early UL127 promoter with and without the upstream unique region. HeLa cells were transfected in triplicate with either plasmid pCL3+, containing wild-type sequence upstream of the promoter, or plasmid pCL dl−694/−583, containing a deletion between −694 and −583, plus plasmid pSVCS, which expresses the viral IE1 and IE2 genes. The mean percent acetylation of [14C]chloramphenicol and standard deviation were determined for the same number of cells as described in Materials and Methods.

Effect of the NF1 sites.

Our investigators reported previously that replacement of the unique region with heterologous DNA increases basal levels of transcription from the UL127 promoter (35). The unique region from −694 to −583 was shown previously to contain two binding sites for transcriptional regulatory protein NF1 (23). To determine whether cellular NF1 regulates UL127 promoter activity, the two binding sites for this transcription factor were mutated in parental plasmid pLC3+ to generate pLC+NF1mut, as diagrammed in Fig. 2. Using the sensitive luciferase assay, the basal activity of the UL127 promoter in pLC+NF1mut was compared to that of pLC3+ and pLC dl−694/−583, which lacks the unique region. Downstream of the MIE enhancer-containing promoter was the CAT gene, which served as an internal control. HFF cells were transfected in triplicate, and the LUX activity relative to pLC3+ was determined, as described in Materials and Methods. There was a 24-fold increase in LUX activity for expression plasmid pLC dl−694/−583 (Fig. 2). Mutation of the NF1 sites in plasmid pLC3+NF1mut had no effect on the basal LUX activity. In contrast, CAT activity from the divergent MIE promoter was the same for all plasmids (data not shown). The data suggest that the NF1 sites are not responsible for the repression of the UL127 promoter.

Construction of recombinant viruses.

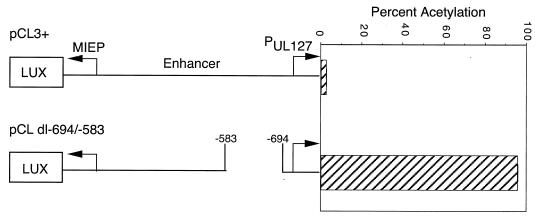

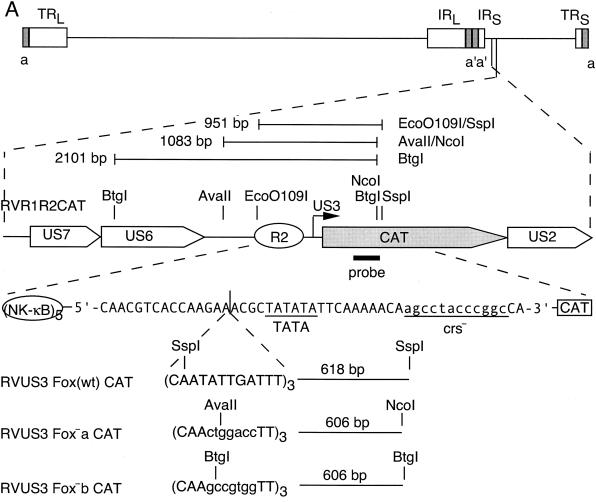

Recombinant viruses were made to determine the role of the other binding sites in the context of a viral infection. Mutations were made in the core sequences of the Fox-like, su(Hw), and CDP binding sites of the UL127 promoter driving expression of the CAT gene (Fig. 3A). To analyze the role of orientation and position of these sites relative to the TATA box, the regions between −694 and −640 and between −694 and −583 were reversed. Mutations in the recombinant viruses were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion followed by Southern blot hybridization with a 32P-labeled CAT-specific probe as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3B). We made a second mutation in the core of the Fox-like site (Fig. 3C, Fox−b). The same seven nucleotides were mutated as in the Fox−a virus, but they were changed to a different sequence. Southern blot analysis confirmed the mutation in the Fox-like site (Fig. 3D, Fox−b). Recombinant viruses were isolated from multiple transfections, plaque purified, analyzed, and characterized, with no observable growth differences between isolates in cell culture.

FIG. 3.

Recombinant viruses with mutations in transcription factor binding sites upstream of the UL127 TATA box. (A) Diagram of recombinant viruses with the MIE promoter and divergent UL127 promoter and the downstream CAT gene. Nucleotide positions are given relative to the MIE promoter +1 transcription start site. The putative binding sites are based on sequence analysis for the transcription factors FoxA, su(Hw), and CDP. Mutations were made in each binding site that introduced a new restriction endonuclease site. Expected DNA fragment sizes after restriction endonuclease digestion are indicated. Sequences between −694 and −640 and between −694 and −583 were reversed (R). (B) Southern bolt analysis was performed with a 32P-labeled NcoI/EcoRI DNA fragment of the CAT gene, as described in Materials and Methods. Each recombinant virus was compared to RVdlMCAT wt, which contains wild-type unique region and the UL127 promoter. Lanes: 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, RVdlMCAT wt; 2, RVdlMCAT Fox−a; 4, RVdlMCAT su(Hw)−; 6, RVdlMCAT CDP−; 8, RVdlMCAT −694/−640R; 10, RVdlMCAT −694/−583R. (C) A second mutation in the Fox site introduced a PflMI restriction endonuclease site in RVdlMCAT Fox−b. Expected DNA fragment sizes after restriction endonuclease digestion are indicated. (D) Southern blot analysis of RVdlMCAT Fox−b was performed with a 32P-labeled NcoI/EcoRI DNA fragment of the CAT gene and compared with RVdlMCAT wt. Lanes: 1, RVdlMCAT wt; 2, RVdlMCAT Fox−b. Restriction endonucleases are designated. Std, DNA molecular mass markers in base pairs (bp).

Effect of mutations on transcription from the UL127 promoter.

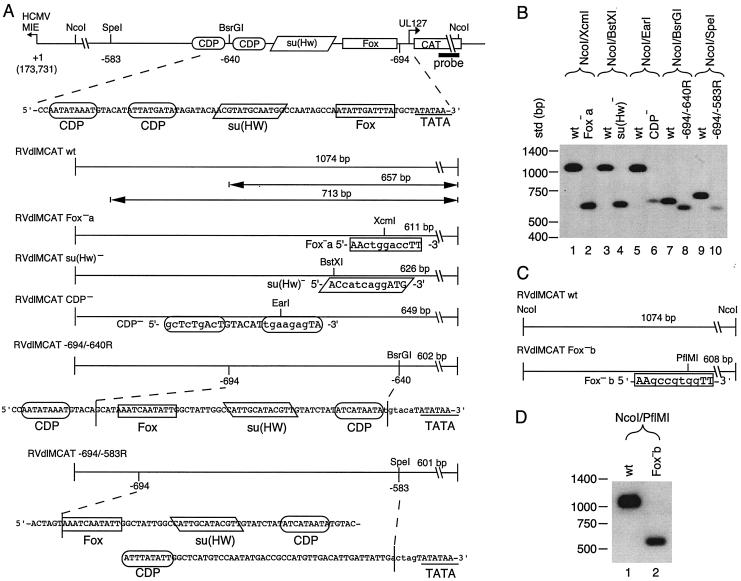

To test the effect of the mutations upstream of the UL127 promoter on downstream transcription in the context of a viral infection, HFFs were infected at approximately 5 PFU per cell with recombinant viruses RVdlMCAT wt, RVdlMCAT Fox−a, RVdlMCAT su(Hw)−, RVdlMCAT CDP−, RVdlMCAT −694/−640R, or RVdlMCAT −694/−583R. Cytoplasmic RNA was harvested at 24 and 48 h postinfection (p.i.), and steady-state levels of UL127/CAT RNA were determined by RNase protection assay with antisense UL127/CAT riboprobe as described previously (35). Meier and Pruessner (41) reported that mutations between −583 and −300 negatively affected the level of IE1 transcription. To address concerns that mutations near the UL127 TATA box might affect the MIE promoter, an RNase protection assay was performed. When US3 and IE1 RNA levels were compared, there were no differences detected for any of the recombinant viral RNAs (data not shown). Mutations in the unique region did not affect transcription from either the MIE or US3 promoters. Antisense IE1 riboprobe was used as a control for equivalent MOI (Fig. 4A). Mutations in the su(Hw) and CDP sites had little to no effect on steady-state UL127/CAT RNA levels (Fig. 4A, lanes 3, 4, 10, and 11). However, when the Fox-like site was mutated, a substantial increase in UL127/CAT RNA was observed at 24 and 48 h p.i. (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 9). When the orientation of the approximately 50-bp region was reversed (−694 to −640), the effect on the RNA level was minimal at 24 h and slightly greater at 48 h p.i. (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 12). When the orientation of the larger 111-bp region was reversed (−694 to −583), transcription was increased modestly at both 24 and 48 h p.i. (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 and 13).

FIG. 4.

Steady-state levels of RNA transcribed from the wild-type or mutant UL127 promoters. HFF cells were infected with approximately 5 PFU of the various recombinant viruses/cell, and cytoplasmic RNA was harvested at either 24 or 48 h p.i. RNAs were analyzed by RNase protection assay as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Comparison of wt with various mutants. Lanes: 1 and 8, RVdlMCAT wt; 2 and 9, RVdlMCAT Fox−a; 3 and 10, RVdlMCAT su(Hw)−; 4 and 11, RVdlMCAT CDP−; 5 and 12, RVdlMCAT −694/−640R; 6 and 13, RVdlMCAT −694/−583R; 7, mock-infected cells. Std, 32P-labeled DNA molecular mass markers in nucleotides (nt). (B) Comparison of wt with Fox−a and Fox−b. Cytoplasmic RNAs were harvested at 24 h p.i. Lanes: 1, mock-infected cells; 2, RVdlMCAT wt; 3, RVdlMCAT Fox−a; 4, RVdlMCAT Fox−b.

It seemed possible to us that when the Fox sequence was mutated, instead of removing a binding site for a transcriptional repressor, an unknown binding site for a transcriptional activator may have been generated. Therefore, we tested a second mutation in the Fox-like site. RNase protection analysis showed that there was an increase in the level of steady-state UL127/CAT RNA with both the Fox−a and Fox−b mutations (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4). When the Fox binding site, but not the su(Hw) or CDP binding site, was mutated, repression of transcription from the UL127 promoter was greatly decreased.

Effects of mutations on expression of CAT from the UL127 promoter.

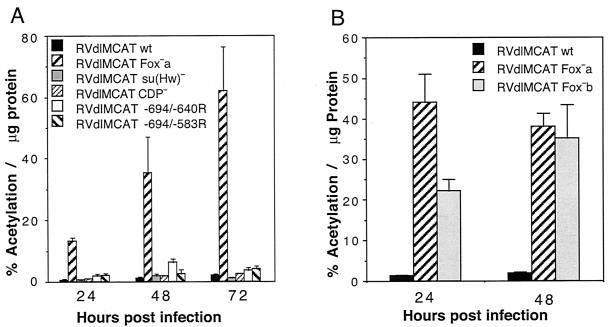

Because CAT RNA is unstable in mammalian cells and CAT enzyme is relatively stable, we also looked at the effects of the mutations on cumulative CAT activity. HFF cells were infected at approximately 5 PFU per cell with recombinant viruses RVdlMCAT wt, RVdlMCAT Fox−a, RVdlMCAT su(Hw)−, RVdlMCAT CDP−, RVdlMCAT −694/−640R, or RVdlMCAT −694/−583R. Infected cells were harvested at various times after infection and analyzed for CAT enzyme activity as described in Materials and Methods. Figure 5A shows that CAT activity was 14- to 31-fold higher with the Fox−a mutation than with the wild-type UL127 promoter. When the upstream regions (−694 to −640R and −694 to −583R) were reversed, there was a modest increase in CAT activity.

FIG. 5.

Effect of mutations upstream of the UL127 promoter on downstream cumulative CAT expression. HFF cells were infected with approximately 5 PFU of the various recombinant viruses/cell, and the amount of CAT activity per microgram of protein was determined at various times after infection as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Comparison of wt with various mutants. (B) Comparison of wt with Fox−a and Fox−b mutants.

There was a significant increase in CAT enzyme activity with both the Fox−a and Fox−b mutations when compared to the wild type (Fig. 5B). The CAT activity was higher with the Fox−a mutation than the Fox−b mutation at 24 h p.i.

Effect of inserting a Fox-like binding site upstream of a heterologous HCMV IE promoter.

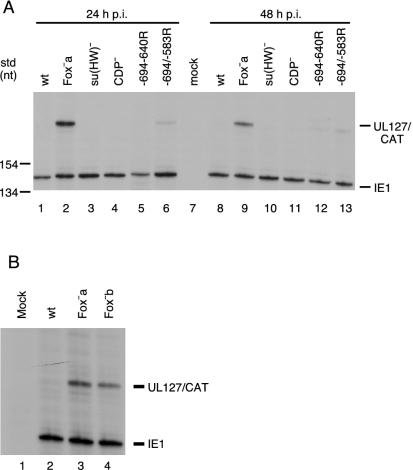

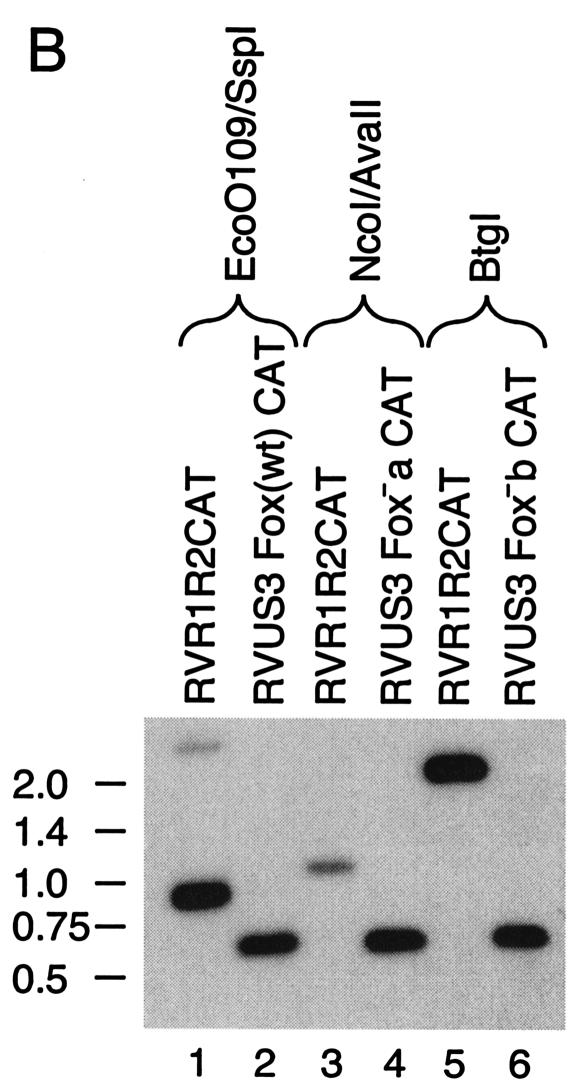

Since mutations in the core of the Fox-like site upstream of the UL127 promoter resulted in a loss of repression of transcription, we tested whether the Fox-like site was sufficient for repression. We constructed recombinant viruses in which three copies of the wild-type Fox (Fox wt) or mutant Fox (Fox−a or Fox−b) sites were placed in the sense orientation between the US3 TATA box and the NF-κB-responsive R2 enhancer in the unique short (US) component of the viral genome (Fig. 6A). The spacing of the Fox-like site 4 bp from the US3 TATA box was identical to that of the UL127 promoter region, with only a 1-base difference. The US3 downstream crs was mutated as previously described (31). Transcription and downstream CAT activities from the US3 promoter are high at early and late times after infection when the crs is mutated (31). Southern blot analysis confirmed that the recombinant viruses were isolated (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Insertion of wild-type or mutant Fox binding sites upstream of a heterologous HCMV promoter. (A) Diagram of recombinant viruses with the IE US3 promoter containing the upstream NF-κB-responsive enhancer (R2). The CAT gene replaced the US3 ORF, and the crs was mutated (underlined lowercase letters). Three copies of the wild-type (wt), mutant a, or mutant b Fox sequence were inserted 4 nt upstream of the IE US3 TATA box. Each contained a restriction endonuclease site as designated. Expected DNA fragment sizes after restriction endonuclease digestion are indicated. (B) Southern blot analysis of viral genome fragments using a 32P-labeled NcoI/EcoRI DNA fragment of the CAT gene. Each recombinant virus is compared to RVR1R2CAT, which contains the wild-type IE US3 promoter. Restriction endonucleases and recombinant viruses are designated. Standard molecular mass markers are designated in kilobases.

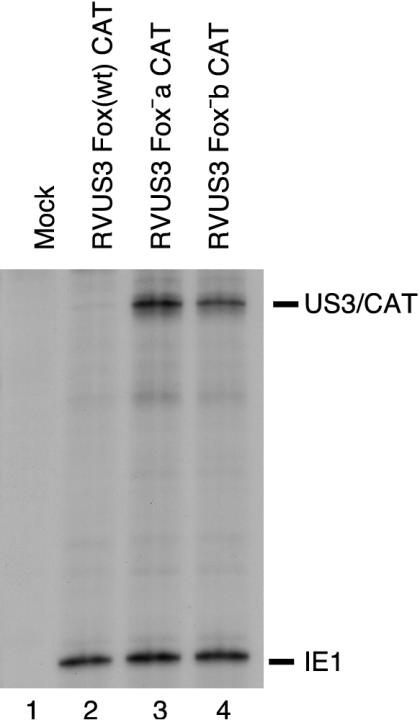

Cytoplasmic RNA was harvested from HFF cells at 24 h after infection at 5 PFU per cell with RVUS3 Fox(wt) CAT, RVUS3 Fox−a CAT, and RVUS3 Fox−b CAT. The steady-state level of US3/CAT RNA was analyzed by RNase protection assay with antisense US3/CAT riboprobe as described previously (31). Antisense IE1 riboprobe was used as a control for equivalent MOI. The Fox-like wild-type sequence was able to greatly repress transcription from the IE US3 promoter (Fig. 7, lane 2), whereas neither the Fox−a nor the Fox−b insertion was able to repress transcription (Fig. 7, lanes 3 and 4).

FIG. 7.

Steady-state RNA levels transcribed from the MIE and US3 promoters. HFF cells were infected with approximately 5 PFU of the various recombinant viruses/cell, and cytoplasmic RNA was harvested at 24 h p.i. RNAs were analyzed by RNase protection assay as described in Materials and Methods. Positions of protected IE1 RNA from the MIE promoter and US3/CAT RNA from the US3 promoter are designated. Lanes: 1, mock-infected cells; 2, RVUS3 Fox(wt) CAT; 3, RVUS3 Fox−a CAT; 4, RVUS3 Fox−b CAT.

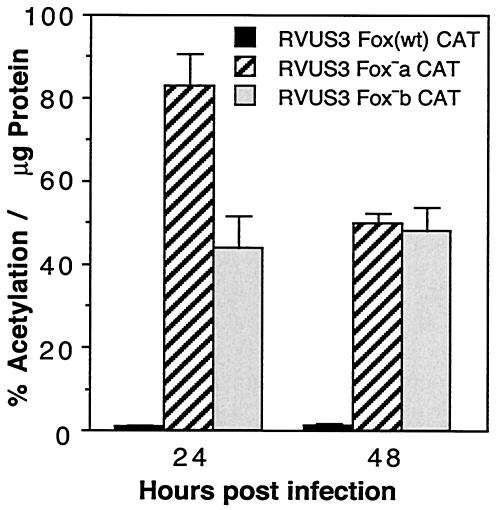

Cumulative CAT enzyme levels were also determined by CAT assay. A significant increase in CAT activity was detected when the Fox-like site was mutated (Fig. 8). There was little CAT enzyme activity when three copies of the wild-type Fox site (Fox wt) were inserted between the TATA box and the R2 enhancer of the IE US3 promoter. However, when either the Fox−a or Fox−b sequence was inserted, there was a 40- to 80-fold increase in CAT activity relative to that with wt Fox sequences. The CAT activity was higher with the Fox−a mutation than the Fox−b mutation at 24 h p.i. Thus, the repressive effect of the Fox sequence was transferable to the heterologous HCMV IE US3 promoter and was sufficient to repress an enhancer-containing promoter.

FIG. 8.

Effect of insertion of wild-type or mutant Fox-like sequence into the IE US3 promoter on downstream cumulative CAT expression. HFF cells were infected in triplicate with approximately 5 PFU of the various recombinant viruses/cell. The amount of CAT activity per microgram of protein was determined at 24 and 48 h after infection as described in Materials and Methods.

Cellular protein binding to the Fox-like site.

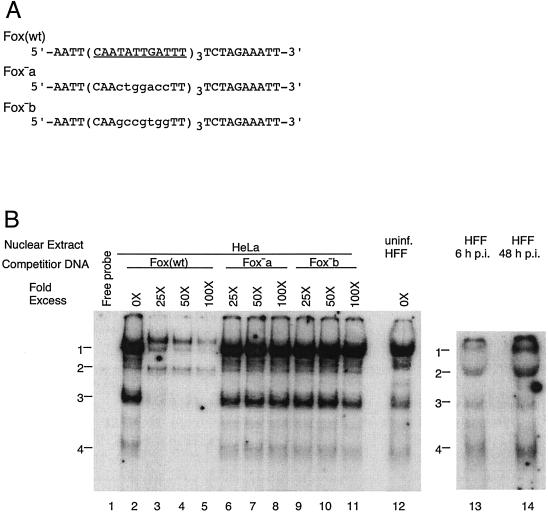

To determine if a cellular protein binds to the Fox-like site, we prepared nuclear extracts from HeLa and uninfected or HCMV-infected HFF cells. We performed EMSA and competition assays with or without a 25-, 50-, or 100-fold molar excess of nonradioactive wild-type, mutant Fox (Fox−) site a or mutant Fox site b as described in Materials and Methods. Without the addition of competitor DNA, EMSA detected four major DNA-protein complexes with either HeLa cell (Fig. 9B, lane 2), uninfected HFF cell (Fig. 9B, lane 12), or infected HFF cell (Fig. 9B, lanes 13 and 14) nuclear extract. Cellular protein may bind to one, two, or three copies of the wild-type Fox-like sites. In competition assays, nonradioactive wild-type Fox-like site DNA competed efficiently for the formation of complexes 1, 3, and 4 but not complex 2 (Fig. 9B, lanes 3 to 5). In contrast, mutant Fox−a and Fox−b DNA did not compete for the specific DNA-protein complexes (Fig. 9B, lanes 6 to 8 and 9 to 11, respectively).

FIG. 9.

EMSA and competition assay with wild-type (wt), mutant Fox site a (Fox−a), or mutant Fox site b (Fox−b). (A) Sequences of the wt and mutant Fox site DNAs. The three copies of the wt site are underlined. Lowercase letters designate the mutant sites. (B) Autoradiogram of EMSA and competition assay using HeLa, uninfected HFF, or infected HFF cell nuclear extract. Lanes: 1, free Fox(wt) probe alone; 2, Fox(wt) probe plus HeLa cell nuclear extract; 3, 4, and 5, wt probe plus HeLa cell nuclear extract in the presence of a 25-, 50-, or 100-fold molar excess of nonradioactive Fox(wt) DNA, respectively; 6, 7, and 8, Fox(wt) probe plus HeLa cell nuclear extract in the presence of a 25-, 50-, or 100-fold molar excess of nonradioactive mutant Fox site a (Fox−a) DNA, respectively; 9, 10, and 11, Fox(wt) probe plus HeLa cell nuclear extract in the presence of a 25-, 50, or 100-fold molar excess of nonradioactive mutant Fox site b (Fox−b) DNA, respectively; 12, Fox(wt) probe plus HFF cell nuclear extract; 13, Fox(wt) probe plus infected HFF cell nuclear extract at 6 h p.i.; 14, Fox(wt) plus infected HFF cell nuclear extract at 48 h p.i. Specific DNA-protein complexes are designated 1 through 4. Free probe is at the bottom of the gel, which is not shown.

Since cellular protein binds to the wild-type Fox-like site and the site is closest in DNA sequence to a consensus FoxA site (HNF-3), we tested if anti-Foxa1 (HNF-3α) or anti-Foxa2 (HNF-3β) affected the specific DNA-protein complexes, as described in Materials and Methods. Similar to normal rabbit serum, anti-Foxa1 or anti-Foxa2 serum had no effect on the specific DNA-protein complexes (data not shown). We conclude that a cellular protein(s) specifically binds to the wild-type Fox-like site but not to the mutant Fox sites.

DISCUSSION

The HCMV UL127 gene is conserved among the HCMV strains sequenced to date (13, 45). Although the UL127 ORF is closed by three stop codons in chimpanzee CMV, the nucleotide sequence is 61% identical (11). The region is not conserved in rhesus, baboon, or African green monkey CMVs or other animal CMVs studied to date (7). The UL127 ORF is not essential for HCMV replication during productive infection in HFF cells in culture, and transcription of the UL127 gene is not detectable by Northern blotting or viral gene microarray assay (6, 35, 42). We propose that a cellular protein represses transcription from the UL127 promoter in HFF cells. Why transcription of the UL127 gene is strongly repressed during productive infection of HFF cells is unknown. The UL127 gene transcription may be repressed for the following reasons: (i) UL127 may be a latency-specific gene and therefore expressed only in cell types that allow for latent infection by HCMV. (ii) UL127 gene transcription may occur only in cell types where the Fox-like repressor is absent. (iii) UL127 may represent a regulatory region and overlap a viral episomal origin of replication used during viral latency. Similar to known origins of replication, this region contains an A/T-rich palindromic structure and potential binding sites for cellular transcription factors. Transcription through this region during productive infection could activate this potential episomal origin of replication. Repression of UL127 transcription could be a means of preventing genome replication from a latency origin.

Our attention was drawn to the Fox-like binding site immediately upstream of the UL127 TATA box. To date, there are no reports of Fox-like repressors in herpesviruses or HFF cells. While the majority of the Fox family members are transcriptional activators, there are also repressors capable of recognizing sequences similar to the site upstream of the UL127 promoter. One such protein is Foxq1 (HFH-1). Mouse-derived Foxq1 represses the telokin promoter when transfected into vascular smooth muscle cells (26). Foxd3 (HFH-2 or genesis) is a well-known repressor necessary for regulation of transcription during embryogenesis in Drosophila (63). Foxd3 is expressed exclusively in embryonic stem cells. Other repressors of the Fox family, Foxp1 and Foxp2, are expressed predominately in lung tissues (56).

The site immediately upstream of the UL127 TATA box has a sequence most similar to a consensus Foxa site. Foxa1 (HNF-3α) stimulates expression from a promoter, but Foxa2 (HNF-3β) represses expression (53). Foxa2 may prevent the binding of positive-acting transcription factors. Anti-Foxa1 or anti-Foxa2 had no effect on the specific DNA-protein complexes generated with the Fox-like site and HeLa cell nuclear extract. In transient-transfection assays, the wild-type early UL127 promoter was repressed in HeLa cells cotransfected with a plasmid that expresses the IE1 and IE2 genes of HCMV, but not when the unique region was deleted. These observations suggest that a functional repressor protein is present in the HeLa and HFF cells.

When we mutated seven nucleotides in the core of the Fox-like binding site (−689 to −683), we detected a significant increase in expression from the UL127 promoter in recombinant virus-infected cells. Mutation of the Fox-like site allowed for an increase in the steady-state level of UL127/CAT mRNA. The cumulative CAT enzyme activity increased at least 25-fold. We did not inadvertently introduce a positive element, since a second mutation confirmed that the sequence was responsible for repression of transcription from the UL127 promoter. Mutation of the NF1, su(Hw), and CDP sites had little to no effect when the wild-type Fox-like site was present.

The Fox-like site is sufficient to mediate repression of an enhancer-containing IE promoter. Three tandem repeats of the wild-type or mutant Fox site were placed between the heterologous IE US3 promoter and the R2 enhancer of HCMV. We had previously demonstrated high transcription and downstream CAT expression from the enhancer-containing US3 promoter when the downstream crs was mutated (31). When the wild-type Fox-like binding site was introduced, gene transcription from the enhancer-containing promoter was essentially eliminated. In contrast, introduction of either the Fox−a or Fox−b mutant did not repress the steady-state level of US3/CAT RNA or the CAT enzyme activity. These data indicated that repression of an early viral promoter conferred by the Fox-like site is transferable to a viral IE promoter. In addition, the Fox-like site is sufficient for blocking the effect of an enhancer on a heterologous, viral promoter.

Since repression of the UL127 promoter is also detected in transient-transfection assays, it is likely that a cellular, and not a viral protein, is responsible for blocking activation of the wild-type UL127 promoter (35). EMSAs demonstrated that cellular protein binds to the wild-type Fox-like sequence but not to mutant sequence. However, anti-Foxa1 or anti-Foxa2 antibody did not have any effect on the cellular protein binding to the Fox-like site. Fox-like repressor proteins have not been identified in HFF cells, which are permissive for HCMV replication.

To our knowledge, this is the first cellular repressor site found embedded in a herpesvirus genome that prevents transcription of an early viral promoter throughout the productive replication cycle of the virus. Whether repression of transcription of the UL127 ORF is unique to HCMV is not known. Why a betaherpesvirus like HCMV represses transcription of this region of the viral genome throughout the reproductive replication cycle requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Stinski laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank Richard Roller for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Our work is supported by grants AI-13562 (M.F.S.) and AI-40130 (J.L.M.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angulo, A., D. Kerry, H. Huang, E.-M. Borst, A. Razinsky, J. Wu, U. Hobom, and P. Ghazal. 2000. Identification of a boundary domain adjacent to the potent human cytomegalovirus enhancer that represses transcription of the divergent UL127 promoter. J. Virol. 74:2826-2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo, A., C. Suto, M. F. Boehm, R. A. Heyman, and P. Ghazal. 1995. Retinoid activation of retinoic acid receptors but not of retinoid X receptors promotes cellular differentiation and replication of human cytomegalovirus in embryonal cells. J. Virol. 69:3831-3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieller, A., B. Pasche, S. Frank, B. Glaser, J. Kunz, K. Witt, and B. Zoll. 2001. Isolation and characterization of the human forkhead gene FOXQ1. DNA Cell Biol. 20:555-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullock, G. C., P. E. Lashmit, and M. F. Stinski. 2001. Effect of the R1 element on expression of the US3 and US6 immune evasion genes of human cytomegalovirus. Virology 288:164-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caswell, R., C. Hagemeier, C.-J. Chiou, G. Hayward, T. Kouzarides, and J. Sinclair. 1993. The human cytomegalovirus 86K immediate early (IE2) protein requires the basic region of the TATA-box binding protein (TBP) for binding, and interacts with TBP and transcription factor TFIIB via region of IE2 required for transcription regulation. J. Gen. Virol. 74:2691-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers, J., A. Angulo, D. Amaratunga, H. Guo, Y. Jiang, J. S. Wan, A. Bittner, K. Frueh, M. R. Jankson, P. A. Peterson, M. G. Erlander, and P. Ghazal. 1999. DNA microarrays of the complex human cytomegalovirus genome: profiling kinetic class with drug sensitivity of viral gene expression. J. Virol. 73:5757-5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, Y.-J., C.-J. Chiou, Q. Huang, and G. S. Hayward. 1996. Synergistic interactions between overlapping binding sites for the serum response factor and ELK-1 proteins mediate both basal enhancement and phorbol ester responsiveness of primate cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoters in monocyte and T-lymphocyte cell types. J. Virol. 70:8590-8605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chee, M. A., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Horsnell, C. A. Hutchison, T. Kouzarides, J. A. Martignetti, E. Preddie, S. C. Satchwell, P. Tomlinson, K. M. Weston, and B. G. Barrell. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherrington, J. M., E. L. Khoury, and E. S. Mocarski. 1991. Human cytomegalovirus ie2 negatively regulates α gene expression via a short target sequence near the transcription start site. J. Virol. 65:887-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clevidence, D. E., D. G. Overdier, W. Tao, X. Qian, L. Pani, E. Lai, and R. H. Costa. 1993. Identification of nine tissue-specific transcription factors of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/forkhead DNA-binding-domain family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3948-3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davison, A. J., A. Dolan, P. Akter, C. Addison, D. J. Dargan, D. J. Alcendor, D. J. McGeoch, and G. S. Hayward. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus genome revisited: comparison with the chimpanzee cytomegalovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 84:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Wet, J. R., K. V. Wood, M. DeLuca, D. R. Helinski, and S. Subramani. 1987. Firefly luciferase gene: structure and expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:725-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn, W., C. Chou, H. Li, R. Hai, D. Patterson, V. Stolc, H. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eskild, W., J. Simard, V. Hansson, and S. Guerin. 1994. Binding of a member of the NF1 family of transcription factors to two distinct cis-acting elements in the promoter and 5′-flanking region of the human cellular retinol binding protein 1 gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 8:732-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghazal, P., H. Lubon, C. Reynolds-Kohler, L. Hennighausen, and J. A. Nelson. 1990. Interactions between cellular regulatory proteins and a unique sequence region in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter. Virology 174:18-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghazal, P., and, and J. A. Nelson. 1991. Enhancement of RNA polymerase II initiation complexes by a novel DNA control domain downstream from the cap site of the cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter. J. Virol. 65:2299-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorman, C. M., L. F. Moffatt, and B. H. Howard. 1982. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:1044-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham, F. L., and A. J. van der Eb. 1973. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology 52:456-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greaves, R. F., J. M. Brown, J. Vieira, and E. S. Mocarski. 1995. Selectable insertion and deletion mutagenesis of the human cytomegalovirus genome using the E. coli guanosine phosphoribosyl transferase (gpt) gene. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2151-2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greaves, R. F., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72:366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagemeier, C., S. Walker, R. Caswell, T. Kouzarides, and J. Sinclair. 1992. The human cytomegalovirus 80-kilodalton but not the 72-kilodalton immediate-early protein transactivates heterologous promoters in a TATA box-dependent mechanism and interacts directly with TFIID. J. Virol. 66:4452-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinemeyer, T., E. Wingender, I. Reuter, H. Hermjakob, A. E. Kel, O. V. Kel, E. V. Ignatieva, E. A. Ananko, O. A. Podkolodnaya, F. A. Kolpakov, N. L. Podkolodny, and N. A. Kolchanov. 1998. Databases on transcriptional regulation: TRANSFAC, TRRD and COMPEL. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:362-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennighausen, L., and B. Fleckenstein. 1986. Nuclear factor 1 interacts with five DNA elements in the promoter region of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene. EMBO J. 5:1367-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermiston, T. W., C. L. Malone, and M. F. Stinski. 1990. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early two protein region involved in negative regulation of the major immediate-early promoter. J. Virol. 64:3532-3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermiston, T. W., C. L. Malone, P. R. Witte, and M. F. Stinski. 1987. Identification and characterization of the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early region 2 gene that stimulates gene expression from an inducible promoter. J. Virol. 61:3214-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoggatt, A. M., A. M. Kriegel, A. F. Smith, and B. P. Herring. 2000. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 homologue 1 (HFH-1) represses transcription of smooth muscle-specific genes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31162-31170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahroude. 1996. An NF1-like protein functions as a repressor of the von Willebrand factor promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21413-21421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jupp, R., S. Hoffmann, R. M. Stenberg, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1993. Human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein interacts with promoter-bound TATA-binding protein via a specific region distinct from the autorepression domain. J. Virol. 67:7539-7546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieg, P. A., and D. A. Melton. 1987. In vitro RNA synthesis with SP6 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol. 155:397-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang, D., S. Gebert, H. Arlt, and T. Stamminger. 1995. Functional interaction between the human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton IE2 protein and the cellular transcription factor CREB. J. Virol. 69:6030-6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lashmit, P. E., M. F. Stinski, E. A. Murphy, and G. C. Bullock. 1998. A cis-repression sequence adjacent to the transcription start site of the human cytomegalovirus US3 gene is required to down regulate gene expression at early and late times after infection. J. Virol. 72:9575-9584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, G., J. Wu, P. Luu, P. Ghazal, and O. Flores. 1996. Inhibition of the association of RNA polymerase II with the preinitiation complex by a viral transcriptional repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2570-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, B., T. W. Hermiston, and M. F. Stinski. 1991. A cis-acting element in the major immediate early (IE) promoter of human cytomegalovirus is required for negative regulation by IE2. J. Virol. 65:897-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lukac, D. M., J. R. Manuppello, and J. C. Alwine. 1994. Transcriptional activation by the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins: requirements for simple promoter structures and interactions with multiple components of the transcription complex. J. Virol. 68:5184-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Lukac, D. M., N. Y. Harel, N. Tanese, and J. C. Alwine. 1997. TAF-like functions of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins. J. Virol. 71:7227-7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundquist, C. A., J. L. Meier, and M. F. Stinski. 1999. A strong negative transcriptional regulatory region between the human cytomegalovirus UL127 gene and the major immediate early enhancer. J. Virol. 73:9039-9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macias, M. P., L. Huang, P. E. Lashmit, and M. F. Stinski. 1996. Cellular and viral protein binding to a cytomegalovirus promoter transcription initiation site: effects on transcription. J. Virol. 70:3628-3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macias, M. P., and M. F. Stinski. 1993. An in vitro system for human cytomegalovirus immediate early 2 protein (IE2)-mediated site-dependent repression of transcription and direct binding of IE2 to the major immediate early promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:707-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maidji, E., E. Percivalle, G. Gerna, S. Fisher, and L. Pereira. 2002. Transmission of human cytomegalovirus from infected uterine microvascular endothelial cells to differentiating placental cytotrophoblasts. Virology 304:53-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malone, C. L., D. H. Vesole, and M. F. Stinski. 1990. Transactivation of a human cytomegalovirus early promoter by gene products from the immediate-early gene IE2 and augmentation by IE1: mutational analysis of the viral proteins. J. Virol. 64:1498-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchini, A., H. Liu, and H. Ahu. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus with IE-2 (UL122) deleted fails to express early lytic genes. J. Virol. 75:1870-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meier, J. L., and J. A. Pruessner. 2000. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer region is required for efficient viral replication and immediate-early expression. J. Virol. 74:1602-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 1997. Effect of a modulator deletion on transcription of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early genes in infected undifferentiated and differentiated cells. J. Virol. 71:1246-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 1996. Regulation of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression. Intervirology 39:331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mocarski, E. S., G. Kemble, J. Lyle, and R. F. Greaves. 1996. A deletion mutant in the human cytomegalovirus gene encoding IE1 491aa is replication defective due to a failure in autoregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11321-11326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy, E., D. Yu, J. Grimwood, J. Schmutz, M. Dickson, M. A. Jarvis, G. Hahn, J. A. Nelson, R. M. Myers, and T. E. Shenk. 2003. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14976-14981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Connor, M. J., W. Stunkel, C. H. Koh, H. Zimmermann, and H. U. Bernard. 2000. The differentiation-specific factor CDP/Cut represses transcription and replication of human papillomaviruses through a conserved silencing element. J. Virol. 74:401-410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Connor, M. J., W. Stunkel, H. Zimmermann, C.-H. Koh, and H.-U. Bernard. 1998. A novel YY1-independent silencer represses the activity of the human papillomavirus type 16 enhancer. J. Virol. 72:10083-10092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osada, S. 1997. Nuclear factor 1 family proteins bind to the silencer element in the rat glutathione transferase P gene. J. Biochem. 121:355-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osada, S., T. Ikeda, M. Xu, T. Nishihara, and M. Imagawa. 1997. Identification of the transcriptional repression domain of nuclear factor 1-A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238:744-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Overdier, D. G., A. Porcella, and R. H. Costa. 1994. The DNA-binding specificity of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/forkhead domain is influenced by amino acid residues adjacent to the recognition helix. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:2755-2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pizzorno, M. C., M. A. Mullen, Y. N. Chang, and G. S. Hayward. 1991. The functionally active IE2 immediate-early regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus is an 80-kilodalton polypeptide that contains two distinct activator domains and a duplicated nuclear localization signal. J. Virol. 65:3839-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 53.Sawaya, P. L., and D. S. Luse. 1994. Two members of the HNF-3 family have opposite effects on a lung transcriptional element; HNF-3 alpha stimulates and HNF-3 beta inhibits activity of region I from the Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP) promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 269:22211-22216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidbauer, M., H. Budka, W. Ulrich, and P. Ambros. 1989. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease of the brain in AIDS and connatal infection: a comparative study by histology, immunocytochemistry, and in situ DNA hybridization. Acta Neuropathol. (Berlin) 79:286-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scott, K. S., and P. K. Geyer. 1995. Effects of the su(Hw) insulator protein on the expression of the divergently transcribed Drosophila yolk protein genes. EMBO J. 14:6258-6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shu, W., H. Yang, L. Zhang, M. M. Lu, and E. E. Morrisey. 2001. Characterization of a new subfamily of winged-helix/forkhead (Fox) genes that are expressed in the lung and act as transcriptional repressors. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27488-27497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sinzger, C., B. Plachter, A. Grefte, A. S. H. Gouw, T. H. The, and G. Jahn. 1996. Tissue macrophages are infected by human cytomegalovirus. J. Infect. Dis. 173:240-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spana, C., D. A. Harrison, and V. G. Corces. 1988. The Drosophila melanogaster suppressor of hairy-wing protein binds to specific sequences of the gypsy retrotransposon. Genes Dev. 2:1414-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spector, D. H. 1996. Activation and regulation of human cytomegalovirus early genes. Intervirology 39:361-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stenberg, R. M. 1996. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early gene. Intervirology 39:343-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stinski, M. F. 1999. Cytomegalovirus promoter for expression in mammalian cells, p. 211-233. In J. M. Fernandez and J. P. Hoeffler (ed.), Gene expression systems: using nature for the art of expression. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 62.Stinski, M. F. 1976. Human cytomegalovirus: glycoproteins associated with virions and dense bodies. J. Virol. 19:594-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sutton, J., R. Costa, M. Klug, L. Field, D. Xu, D. A. Largaespada, C. F. Fletcher, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, M. Klemsz, and R. Hormas. 1996. Genesis, a winged helix transcriptional repressor with expression restricted to embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23126-23133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thrower, A. R., G. C. Bullock, J. E. Bissell, and M. F. Stinski. 1996. Regulation of a human cytomegalovirus immediate early gene (US3) by a silencer/enhancer combination. J. Virol. 70:91-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu, J., R. Jupp, R. M. Stenberg, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1993. Site-specific inhibition of RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex assembly by human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein. J. Virol. 67:7547-7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]